Abstract

Introduction

No predictive models for long-term mortality in critically ill patients with acute kidney injury (AKI) exist. We aimed to develop and validate two predictive models for one-year mortality in patients with AKI based on data (1) on intensive care unit (ICU) admission and (2) on the third day (D3) in the ICU.

Methods

This substudy of the FINNAKI study comprised 774 patients with early AKI (diagnosed within 24 hours of ICU admission). We selected predictors a priori based on previous studies, clinical judgment, and differences between one-year survivors and non-survivors in patients with AKI. We validated the models internally with bootstrapping.

Results

Of 774 patients, 308 (39.8%, 95% confidence interval (CI) 36.3 to 43.3) died during one year. Predictors of one-year mortality on admission were: advanced age, diminished premorbid functional performance, co-morbidities, emergency admission, and resuscitation or hypotension preceding ICU admission. The area under the receiver operating characteristic curve (AUC) (95% CI) for the admission model was 0.76 (0.72 to 0.79) and the mean bootstrap-adjusted AUC 0.75 (0.74 to 0.75). Advanced age, need for mechanical ventilation on D3, number of co-morbidities, higher modified SAPS II score, the highest bilirubin value by D3, and the lowest base excess value on D3 remained predictors of one-year mortality on D3. The AUC (95% CI) for the D3 model was 0.80 (0.75 to 0.85) and by bootstrapping 0.79 (0.77 to 0.80).

Conclusions

The prognostic performance of the admission data-based model was acceptable, but not good. The D3 model for one-year mortality performed fairly well in patients with early AKI.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Predictive models for mortality provide an estimate of the probability of death in a particular group of patients. Although they cannot replace clinical judgment in decision-making, they are valuable complementary tools as they can give an objective medical research-based assessment of the severity of illness and the associated risk of death [1]. A combination of a physician’s clinical evaluation with a risk estimate given by a predictive model has a better ability to distinguish patients with high or low probabilities of survival than estimates based solely on prediction of a physician or a model [2]. A reliable assessment of the expected course of the disease is essential both for informing patients and their families about the situation and for clinical decision-making, and also when estimating the potential futility of care. In addition, prediction models are useful in benchmarking, that is, comparing the performance of intensive care units (ICUs).

Acute kidney injury (AKI) is a syndrome that affects a marked proportion of critically ill patients [3-5] and is associated with high consumption of healthcare resources, particularly when renal replacement therapy (RRT) is administered [6-9]. AKI is associated with 90-day mortality up to 34% [3] and an increased mortality attributable to AKI persists up to 10 years after hospital discharge [6,9-15]. Even mild AKI is associated with markedly increased long-term mortality [16]. AKI-specific predictive models are needed to identify patients with AKI and with poor outcome.

Models for predicting mortality, such as Acute Physiology and Chronic Health Evaluation (APACHE) [17,18] and Simplified Acute Physiology Score (SAPS) [19,20], have shown only poor to moderate predictive performance in patients with AKI [21,22]. AKI-specific scoring systems have been developed for prediction of hospital [23-26] or 60-day mortality [27-29]. Some of these models are restricted to RRT-treated patients [10,29]. None of these AKI-specific scores have used any of the modern definitions for AKI; Risk, Injury, Failure, Loss of kidney function, and End-stage kidney disease (RIFLE) [30], Acute Kidney Injury Network (AKIN) [31], or Kidney Disease: Improving Global Outcomes (KDIGO) criteria [32]. Most importantly, these AKI-specific scoring systems have not shown adequate discrimination or calibration ability possibly due to significant differences in case mix, advancements in ICU care, and changes in AKI definition over years [21,22]. However, the predictive power of AKI-specific models has been shown to improve with increasing surveillance time [28].

One-year mortality is a relevant patient-centred outcome compared to discharge policy-influenced hospital mortality [33]. Accordingly, we aimed to develop and validate predictive models for one-year mortality of critically ill patients with AKI using data available on ICU admission and another using data collected by the third day of ICU treatment.

Methods

Study patients

We included consecutive patients with early AKI from the Finnish Acute Kidney Injury (FINNAKI) study [3]. The FINNAKI study was conducted in 17 Finnish ICUs between 1 September 2011 and 1 February 2012 [3]. All patients with an emergency admission or with elective postoperative admission with ICU stay expected to exceed 24 hours were enrolled. The following patients were excluded: (1) patients under 18 years of age, (2) intermediate care patients, (3) patients with chronic dialysis, (4) earlier included patients receiving RRT during the previous admission, (5) patients transferred from another study ICU, who were already included in the study for five days, (6) patients without sufficient language skills or without permanent residency in Finland, and (7) organ donors. In the present study we further excluded: (1) patients with AKI diagnosed later than 24 hours after ICU admission, (2) all patients undergoing cardiac surgery due to organizational differences in postoperative care between the participating hospitals, and (3) all patients in one ICU with incomplete data of vasoactive treatment. For patients with multiple admissions, we included the first admission with AKI.

The Ethics committee of the Department of Surgery in Helsinki University Central Hospital approved the FINNAKI study protocol with written, informed consent from patient or proxy and the use of deferred consent. Finnish National Institute of Health approved the collection of data of deceased patients if informed consent could not be obtained.

Data collection

We prospectively collected data from the first five days in the ICU using the Finnish Intensive Care Consortium database maintained by Tieto Ltd (Helsinki, Finland). The data included admission and outcome data, severity of illness scores, physiological measurements, and laboratory values. Additionally, we used a study-specific case report form (CRF) to collect information regarding predetermined chronic illnesses (chronic obstructive pulmonary disease, hypertension, arteriosclerosis, systolic heart failure, chronic kidney diseases, diabetes mellitus, chronic liver failure, ureterolithiasis, coagulopathies, systemic vasculitis, rheumatoid arthritis, organ transplants and malignancies), daily medications, and predetermined risk factors for AKI (hypotension, resuscitation, hypovolaemia by clinicans’ judgement, transfusion of at least 10 red blood cell units, rhabdomyolysis, acute liver failure, low cardiac output, operation within one week prior to ICU admission, and use of radiocontrast dye/aminoglycosides/pepticoglycans that is vancomycin/angiotensin-converting enzyme inhibitor or angiotensin receptor blocker/non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs/amphotericin B/diuretics/metformin/hydroxylethyl starch/gelatin/albumin within 48 hours prior to ICU admission) from patients’ records. The Finnish Population Register Centre provided data regarding vital status at one year from ICU admission (the primary study end point).

Definitions

We used the KDIGO criteria including both changes in serum creatinine and hourly urine output to define and stage AKI [32]. Early AKI was defined as any AKI stage diagnosed within 24 hours of ICU admission. Chronic kidney disease was defined as glomerular filtration rate <60 ml/ml/1.73 m2 for three months [34]. The presence of hypotension (systolic blood pressure <90 mmHg) or resuscitation (haemodynamic collapse requiring cardiopulmonary resuscitation, defibrillation, or administration of epinephrine) within 48 hours preceding ICU admission, organ dysfunctions, and severe sepsis (defined according to the American College of Chest Physicians/Society of Critical Care Medicine criteria [35]) were evaluated by attending physicians. We defined organ failure (OF) as a daily organ-specific Sequential Organ Failure Assessment (SOFA) score >2 [36,37]. The ∆OF was defined as the difference in the number of failed organs on day 3 (D3) versus day 1 (D1) in the ICU [38]. The premorbid functional performance preceding the acute illness was dichotomised: (1) normal or unable to work but no need for assistance in self-care and daily living and (2) some assistance required or totally dependent on assistance.

Model development

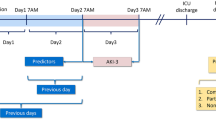

We generated models for one-year mortality using data available at two clinically relevant time points: first, data available on ICU admission (admission model) and, second, on D3 in the ICU (D3 model). We selected candidate predictors for one-year mortality a priori based on previous studies, clinical judgment as recommended [1], and by differences in univariable analyses between one-year survivors and non-survivors in this study. The admission model comprised only predictors available at the time of ICU admission to avoid the possible confounding effect of treatment in the ICU. Age, gender, co-morbidities, premorbid functional performance, type of admission according to SAPS II (scheduled surgical, unscheduled surgical, or medical), APACHE II diagnostic group, and presence/absence of severe sepsis were included in both models. The admission model also included data on presence of hypotension or resuscitation preceding ICU admission. In the D3 model, we included organ-supportive treatments (mechanical ventilation and administration of norepinephrine) on D3 in the ICU, change in the number of registered organ failures including renal failure (∆OF), the worst value of base excess (BE) and platelets on the D3 in the ICU, and highest bilirubin concentration during the first three days in the ICU, and SAPS II points without points for age, chronic health status, admission type, and renal components. We studied the potential existence of collinearity with multiplicative terms.

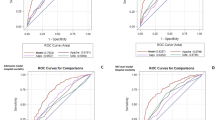

First, we analysed the association between candidate predictors and one-year mortality with multivariable logistic regression analysis separately for both admission and D3 models. We performed backwards elimination at the significance level of P <0.05. We assessed discrimination (the model’s ability to distinguish survivors from non-survivors) by concordance statistic (c-statistic) using the area under the receiver operating characteristic curve (AUC). We regarded AUC values of >0.7, >0.8, and >0.9 as acceptable, good, or excellent, respectively [39]. We evaluated calibration (the model’s ability to accurately predict the number of deaths across different levels of risk) with the Hosmer-Lemeshow goodness-of fit (GoF) test with P value >0.05 indicating good calibration [40]. We assessed the overall predictive accuracy with the Brier score [40], which is the mean squared difference between the observed outcome and predicted risk of death. A low Brier score indicates good model performance (0 for a perfect model). When mortality is 50%, a Brier score of 0.25 would indicate that the model is worthless; for a mortality of 40%, the upper limit of the Brier score is 0.24 [41]. Finally, we calculated the standardized mortality ratios (SMRs) with both models by dividing the number of observed deaths with the predicted number of deaths.

If no data regarding pre-existing chronic illnesses were recorded, we assumed that particular condition not to exist [42]. For continuous data we substituted missing values by the median value of the variable. The proportion of missing data on candidate predictors ranged from 0 to 2.6% in the admission model and from 0 to 6.0% in the D3 model.

For comparison, we determined the discrimination of the SAPS II score when it was used alone as a predictor of one-year mortality.

Model validation

We validated the models internally by bootstrapping. We performed a bootstrap procedure (1,000 draws with replacement) to obtain the bootstrap-adjusted c-statistic index. The bootstrap method randomly draws multiple samples with replacement from the original cohort. The model is developed again in each bootstrap sample yielding a different AUC (c-statistic) to each bootstrap model [40]. Finally, an average of these c-indexes was calculated.

Statistical analysis

We report categorical variables as absolute numbers with percentages and continuous data as median with interquartile ranges (IQRs). Categorical data were compared using the chi-square or Fisher’s exact test when appropriate. We used the Mann-Whitney U test to compare continuous data. We calculated the independent contribution of each variable included in the prediction model by dividing the difference in the −2 log likelihood of the null model and the final model without the particular predictor by the difference in the −2 log likelihood of the null model and the complete final model [43]. This ratio was normalised to presents. Statistical analyses were performed using SPSS Statistics version 20 software (IBM, Armonk, NY, USA) and R version 3.0.3 for Mac (R Foundation for Statistical Computing, Vienna, Austria).

Results

Patients

Of the 774 critically ill patients with early AKI (AKI diagnosed within 24 hours of ICU admission), 399 (51.6%) stayed in the ICU for at least three days. We excluded 274 patients (24% of all 1,141 AKI patients) with AKI occurring later than 24 hours after admission. Figure 1 illustrates the study flow chart. The overall one-year mortality rate for patients with early AKI was 308/774 (39.8%, 95% confidence interval (CI) 36.3 to 43.3%). Of the 308 patients who died within one year, 222 (72%) died in the hospital. The Kaplan-Meier one-year survival plot is shown in Additional file 1. Table 1 presents the characteristics of one-year survivors and non-survivors. No differences in the proportion of patients with severe sepsis, use of RRT in ICU, or in severity of AKI between one-year survivors and non-survivors existed. Treatment restrictions were applied in 202/774 (26.1%) patients.

Admission model

The admission model comprised 774 patients. Table 2 presents the results of the regression analysis with odds ratios (OR, 95% CI) of all significant predictors. Discrimination of the model was acceptable with an AUC (95% CI) of 0.76 (0.72 to 0.79). The model was well calibrated (Hosmer-Lemeshow GoF 10.35, P = 0.24). The mean bootstrap-adjusted AUC of the admission model was 0.75 (95% CI 0.74 to 0.75). The Brier score yielded a value of 0.20 (95% CI 0.20 to 0.20). The logistic regression equation and probability of death with two patient examples are presented in Additional file 2. The bootstrap-adjusted mean SMR (95% CI) was 1.00 (0.92 to 1.09). Altogether 29 patients (3.7%) had a probability of death within one year over 80%, and 24 of those 29 (82.8%) died. Their characteristics are presented in Table 3.

In a subgroup of hospital survivors (552 patients), the predictive ability of the admission model for the one year mortality yielded an AUC value of 0.70 (0.64 to 0.76) with GoF 12.95, P = 0.11). Likewise, the performance of the admission model to predict hospital mortality was acceptable with an AUC (95% CI) of 0.76 (0.72 to 0.79) and calibration of 7.17 by GoF, P = 0.52.

D3 model

The D3 model comprised 398 patients. Of these, 138 were dead by one year (34.7%, 95% CI 29.9 to 39.4%). Table 4 presents the D3 model. Figure 2 illustrates the ROC curve of the D3 model. The D3 model performed well with an AUC (95% CI) of 0.80 (0.75 to 0.85) and calibration of 7.70 by GoF, P = 0.46. The bootstrapped mean AUC was 0.79 (95% CI 0.77 to 0.80). The Brier score yielded a value of 0.17 (95% CI 0.17 to 0.18). The logistic regression equation and calculation of the probability of death are shown in an Additional file 2. The mean SMR (95% CI) of the bootstrapped models was 1.0 (0.89 to 1.13). Nineteen patients (4.8%) had a probability over 80% of death and 16 (84.2%) of them died within one year. All these high-risk patients were medical admissions, four (21.2%) required assistance in their daily living, and they had a median (IQR) of two (one to three) co-morbidities. Their median (IQR) age was 68 (51 to 78) years, modified SAPS II score 34 (12 to 42), BE on D3 -4.7 (-7.6 to -2.1) mmol/l, and maximum bilirubin value by D3 102 (29 to 168) μmol/l. Eighteen (94.7%) still required mechanical ventilation on D3. Additional file 2 presents a patient example.

Among hospital survivors treated in the ICU for at least three days (312 patients) the ability of the model to predict one-year mortality yielded AUC of 0.69 (0.61 to 0.76) and calibration of 7.74 by GoF, P = 0.46.

SAPS II score

The AUC (95% CI) of the SAPS II score alone as a predictor of one-year mortality was 0.68 (0.63 to 0.74).

Discussion

In this follow-up study of the prospective FINNAKI study, we sought to identify factors predicting one-year mortality of critically ill patients with early AKI and to construct predictive models for one-year mortality using data available on ICU admission, and separately, on D3 in the ICU. Severity of the acute illness, advanced age, diminished premorbid functional performance, a higher number of co-morbidities, as well as need for mechanical ventilation on D3 were independent predictors of poor long-term outcome. In contrast, neither the severity of AKI nor the presence of severe sepsis was independently associated with one-year mortality. The prognostic performance of the admission data-based model was acceptable but not good. The discrimination improved with a longer surveillance period and the performance of the D3 model was fairly good with an AUC value of 0.8. Recently, some authors have even considered an AUC of 0.8 excellent [44]. The SAPS II score alone was a poor predictor of long-term outcome.

To the best of our knowledge, the current study is the first to report models for prediction of one-year mortality in non-selected patients with early AKI. Moreover, these models outperform the majority of previously developed models. Of previous AKI-specific scores, Liano et al.’s score [26] performed poorly, while the SHARF score performed fairly well with an AUC 0.8 [12]. These models were tested among hospital survivors of the SHARF score development cohort, and consequently, good performance of the SHARF score was to be expected. Chertow et al. have developed predictive models for 60-day mortality in patients with AKI of on three separate time points (day of diagnosing AKI, day of consultation of a nephrologist, and day of initiation of RRT) [28]. Although the performance of these models improved over time, the discrimination was from poor to moderate (AUC values of 0.62, 0.68 and 0.72, respectively) [28]. Among patients receiving RRT, predictive models have performed better with AUCs from 0.83 [10] to 0.85 [29]. As RRT-treated patients form a homogenous patient cohort, the performances of the models were presumably better.

At ICU admission, the three strongest predictors of death within one year were (1) advanced age, (2) type of ICU admission (medical or emergency surgical admission), and (3) underlying chronic liver failure contributing approximately 37% to the model. An emergency admission has been associated with unfavourable prognosis in several other models [17,19,29]. As in our model, the presence of several co-morbidities has been associated with one-year mortality among patients with severe AKI [10] and also with short-term mortality in patients with AKI [23-29]. Additionally, we found the presence of malignancy, need for resuscitation pre-ICU, and need for assistance in daily living to be strong predictors for one-year mortality (see Table 2). These findings corroborate a recent study that found frailty among older general ICU patients to predict six-month mortality [45]. Interestingly, diabetes was found to be a predictor for better long-term survival in the present study. A total of 203 (26.2%) of the 774 patients with early AKI had diabetes. In the FINNAKI study, 22.0% of the critically ill patients had diabetes and a higher proportion of diabetes was found in patients with AKI (26.6%) than in those without AKI (19.6%) [3]. However, the proportion of diabetics on medication is much lower (4.5%) in the general Finnish population [46,47]. Thus, diabetics were relatively overrepresented in our study population. It thus seems that diabetes predisposes to severe acute illnesses and acute kidney injury. Nevertheless, in this population of ICU patients with AKI, diabetes was associated with improved outcome. Based on our data, we are not able to give any definitive explanation for this finding. However, the finding is somewhat similar to the ‘obesity paradox’: obesity increases the susceptibility for AKI, but is associated with improved survival among patients with RRT-treated severe AKI [48].

Most of the previous AKI-specific models are based on data available at the time of diagnosing AKI. A worse outcome has been found in patients with gradually progressing AKI compared to patients with stable AKI or improving AKI [49]. In line, worsening of organ function over the first three days after initiation of RRT or three to four days after the onset of sepsis has been shown to associate with decreased survival [38,50,51]. Therefore, scores based solely on the data within the first day of ICU or at the time of diagnosing AKI may not be reliable in predicting the outcome of patients with progressive critical illness. In addition, previous studies have shown the predictive performance of models among AKI patients to improve over time [23,28]. Thus, we generated another model using data available by D3 in the ICU. In line with other AKI-specific models, we found that (1) advanced age, (2) need for mechanical ventilation, and (3) hepatic dysfunction (the highest bilirubin value) were the strongest predictors of long-term mortality [23-26,28,29] contributing to 51% of the D3 model (see Table 4). Of patients with a probability of over 80% of dying, 95% needed mechanical ventilation on D3. Besides advanced age, also the lowest base excess value on D3 reflecting the severity of metabolic acidosis of varying aetiology was a predictor of worse outcome. Thus, among patients with early AKI, other organ failures on D3 that have been refractory to ICU treatment or have developed while in ICU, serve as predictors of adverse long-term outcome.

Interestingly, we did not find the presence of severe sepsis to associate with one-year mortality. This finding is in contrast to two AKI-specific models based on data from years 1997 to 1998 [24] and 1999 to 2001 [28] that have included the presence of severe sepsis as a predictor of adverse outcome. Recent studies have reported reduced mortality in severe sepsis suggesting a beneficial effect of increased knowledge, better recognition, and earlier treatment of these patients [52,53]. This improved performance in the treatment of septic patients may explain why severe sepsis did not remain as an independent predictor in our models. Correspondingly, the increased awareness and advances in the treatment of AKI [30-32] may account for the somewhat unexpected finding that severity of AKI was not an independent predictor of one-year mortality.

A model with good performance for short-term mortality also predicts long-term mortality well if most deaths occur in the hospital. In the present study, the majority of the deaths (72%) occurred in the hospital. This partly explains that the admission model predicted hospital and one-year mortality equally well. Among hospital survivors treated in the ICU for at least three days, the D3 model performed worse (AUC 0.69) than it did in the overall population, suggesting that the discrimination ability of the D3 diminishes after hospital discharge.

Our study has several strengths. The participating ICUs represent both academic and non-academic ICUs, and their referral areas cover 85% of the Finnish adult population [3]. All data were recorded prospectively. We defined and staged AKI by changes in both serum creatinine and hourly urine output with the latest AKI definition [32]. The models comprised data that were routinely collected during ICU stay and are easily repeatable. However, several limitations need to be discussed. First, we selected candidate predictors based on previous studies and clinical judgement. Some significant factors may have been excluded from the analysis due to low frequency of the variable or large proportion of missing data (we avoided including variables with >5% of missing data) [54]. In addition, we had to exclude 4.9% of AKI patients with missing reliable cardiovascular SOFA score (Figure 1). Second, our study was not multinational, which may limit the generalizability of the results. However, the predictors of adverse outcome found in the D3 model were in line with the previous AKI-specific models [23-29]. In addition, the mean bootstrap-adjusted SMRs of both models support the validity of models. Third, our models include rather many predictor variables, which may increase the risk for overfitting. However, the large simulation study by Vittinghoff and McCulloch demonstrated that causal influences can generally be adequately analysed even when there are no more than five to nine outcome events per predictor variable [55]. Finally, though we were not able to validate our models externally, we used the bootstrapping technique for validation that is considered as the preferred method for internal validation [40].

Conclusions

We developed two new predictive models for one-year mortality among critically ill patients with early AKI using data available on ICU admission and on D3. The prognostic performance of the admission model was acceptable, but not good, whereas the performance of the D3 model was fairly good.

Key messages

-

A predictive model for one-year mortality for critically ill patients with early AKI based on data on D3 performed fairly well.

-

Severity of illness, advanced age, poor premorbid functional performance, a high number of co-morbidities, and need for mechanical ventilation on D3 were predictors of a poor long-term outcome.

-

Severe sepsis and the severity of AKI were not independent predictors.

Abbreviations

- ∆OF:

-

difference in the number of failed organs on day 3 versus day 1 in the ICU

- AKI:

-

acute kidney injury

- AKIN:

-

Acute Kidney Injury Network

- APACHE:

-

Acute Physiology and Chronic Health Evaluation

- AUC:

-

area under the receiver operating characteristic curve

- BE:

-

base excess

- CI:

-

confidence interval

- CRF:

-

case report form

- GoF:

-

goodness of fit

- ICU:

-

intensive care unit

- IQR:

-

interquartile range

- KDIGO:

-

Kidney Disease: Improving Global Outcomes

- OF:

-

organ failure

- OR:

-

odds ratio

- RIFLE:

-

Risk, Injury, Failure, Loss of kidney function, and End-stage kidney disease

- RRT:

-

renal replacement therapy

- SAPS:

-

Simplified Acute Physiology Score

- SMR:

-

standardized mortality ratio

- SOFA:

-

Sequential Organ Failure Assessment

References

Moons KG, Altman DG, Vergouwe Y, Royston P. Prognosis and prognostic research: application and impact of prognostic models in clinical practice. BMJ. 2009;338:b606.

Knaus WA, Harrell Jr FE, Lynn J, Goldman L, Phillips RS, Connors Jr AF, et al. The SUPPORT prognostic model. Objective estimates of survival for seriously ill hospitalized adults. Study to understand prognoses and preferences for outcomes and risks of treatments. Ann Intern Med. 1995;122:191–203.

Nisula S, Kaukonen KM, Vaara ST, Korhonen AM, Poukkanen M, Karlsson S, et al. Incidence, risk factors and 90-day mortality of patients with acute kidney injury in Finnish intensive care units: the FINNAKI study. Intensive Care Med. 2013;39:420–8.

Medve L, Antek C, Paloczi B, Kocsi S, Gartner B, Marjanek Z, et al. Epidemiology of acute kidney injury in Hungarian intensive care units: a multicenter, prospective, observational study. BMC Nephrol. 2011;12:43.

Ostermann M, Chang RW. Acute kidney injury in the intensive care unit according to RIFLE. Crit Care Med. 2007;35:1837–43. quiz 1852.

Åhlstrom A, Tallgren M, Peltonen S, Räsänen P, Pettilä V. Survival and quality of life of patients requiring acute renal replacement therapy. Intensive Care Med. 2005;31:1222–8.

Laukkanen A, Emaus L, Pettilä V, Kaukonen KM. Five-year cost-utility analysis of acute renal replacement therapy: a societal perspective. Intensive Care Med. 2013;39:406–13.

Gopal I, Bhonagiri S, Ronco C, Bellomo R. Out of hospital outcome and quality of life in survivors of combined acute multiple organ and renal failure treated with continuous venovenous hemofiltration/hemodiafiltration. Intensive Care Med. 1997;23:766–72.

Korkeila M, Ruokonen E, Takala J. Costs of care, long-term prognosis and quality of life in patients requiring renal replacement therapy during intensive care. Intensive Care Med. 2000;26:1824–31.

Bagshaw SM, Laupland KB, Doig CJ, Mortis G, Fick GH, Mucenski M, et al. Prognosis for long-term survival and renal recovery in critically ill patients with severe acute renal failure: a population-based study. Crit Care. 2005;9:R700–9.

Liano F, Felipe C, Tenorio MT, Rivera M, Abraira V, Saez-de-Urturi JM, et al. Long-term outcome of acute tubular necrosis: a contribution to its natural history. Kidney Int. 2007;71:679–86.

Lins RL, Elseviers MM, Daelemans R. Severity scoring and mortality 1 year after acute renal failure. Nephrol Dial Transplant. 2006;21:1066–8.

Fuchs L, Lee J, Novack V, Baumfeld Y, Scott D, Celi L, et al. Severity of acute kidney injury and two-year outcomes in critically ill patients. Chest. 2013;144:866–75.

Van Berendoncks AM, Elseviers MM, Lins RL, Group SS. Outcome of acute kidney injury with different treatment options: long-term follow-up. Clin J Am Soc Nephrol. 2010;5:1755–62.

Gammelager H, Christiansen CF, Johansen MB, Tonnesen E, Jespersen B, Sorensen HT. One-year mortality among Danish intensive care patients with acute kidney injury: a cohort study. Crit Care. 2012;16:R124.

Linder A, Fjell C, Levin A, Walley KR, Russell JA, Boyd JH. Small acute increases in serum creatinine are associated with decreased long-term survival in the critically ill. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2014;189:1075–81.

Knaus WA, Draper EA, Wagner DP, Zimmerman JE. APACHE II: a severity of disease classification system. Crit Care Med. 1985;13:818–29.

Zimmerman JE, Wagner DP, Draper EA, Wright L, Alzola C, Knaus WA. Evaluation of acute physiology and chronic health evaluation III predictions of hospital mortality in an independent database. Crit Care Med. 1998;26:1317–26.

Le Gall JR, Lemeshow S, Saulnier F. A new Simplified Acute Physiology Score (SAPS II) based on a European/North American multicenter study. JAMA. 1993;270:2957–63.

Moreno RP, Metnitz PG, Almeida E, Jordan B, Bauer P, Campos RA, et al. SAPS 3–From evaluation of the patient to evaluation of the intensive care unit. Part 2: Development of a prognostic model for hospital mortality at ICU admission. Intensive Care Med. 2005;31:1345–55.

Uchino S, Bellomo R, Morimatsu H, Morgera S, Schetz M, Tan I, et al. External validation of severity scoring systems for acute renal failure using a multinational database. Crit Care Med. 2005;33:1961–7.

Douma CE, Redekop WK, van der Meulen JH, van Olden RW, Haeck J, Struijk DG, et al. Predicting mortality in intensive care patients with acute renal failure treated with dialysis. J Am Soc Nephrol. 1997;8:111–7.

Lins RL, Elseviers M, Daelemans R, Zachee P, Zachee P, Gheuens E, et al. Prognostic value of a new scoring system for hospital mortality in acute renal failure. Clin Nephrol. 2000;53:10–7.

Lins RL, Elseviers MM, Daelemans R, Arnouts P, Billiouw JM, Couttenye M, et al. Re-evaluation and modification of the Stuivenberg Hospital Acute Renal Failure (SHARF) scoring system for the prognosis of acute renal failure: an independent multicentre, prospective study. Nephrol Dial Transplant. 2004;19:2282–8.

Mehta RL. Refining predictive models in critically ill patients with acute renal failure. J Am Soc Nephrol. 2002;13:1350–7.

Liano F, Gallego A, Pascual J, Garcia-Martin F, Teruel JL, Marcen R, et al. Prognosis of acute tubular necrosis: an extended prospectively contrasted study. Nephron. 1993;63:21–31.

Chertow GM, Lazarus JM, Paganini EP, Allgren RL, Lafayette RA, for the Auriculin Anaritide Acute Renal Failure Study Group, et al. Predictors of mortality and the provision of dialysis in patients with acute tubular necrosis. J Am Soc Nephrol. 1998;9:692–8.

Chertow GM, Soroko SH, Paganini EP, Cho KC, Himmelfarb J, Ikizler TA, et al. Mortality after acute renal failure: models for prognostic stratification and risk adjustment. Kidney Int. 2006;70:1120–6.

Demirjian S, Chertow GM, Zhang JH, O'Connor TZ, Vitale J, Paganini EP, et al. Model to predict mortality in critically ill adults with acute kidney injury. Clin J Am Soc Nephrol. 2011;6:2114–20.

Bellomo R, Ronco C, Kellum JA, Mehta RL, Palevsky P. Acute renal failure - definition, outcome measures, animal models, fluid therapy and information technology needs: the Second International Consensus Conference of the Acute Dialysis Quality Initiative (ADQI) Group. Crit Care. 2004;8:R204–12.

Mehta RL, Kellum JA, Shah SV, Molitoris BA, Ronco C, Warnock DG, et al. Acute Kidney Injury Network: report of an initiative to improve outcomes in acute kidney injury. Crit Care. 2007;11:R31.

Kidney Disease: Improving Global Outcomes (KDIGO) acute kidney injury work group. KDIGO clinical practice guideline for acute kidney injury. Kidney Inter. 2012; 2:1–138.

Brinkman S, Abu-Hanna A, de Jonge E, de Keizer NF. Prediction of long-term mortality in ICU patients: model validation and assessing the effect of using in-hospital versus long-term mortality on benchmarking. Intensive Care Med. 2013;39:1925–31.

K/DOQI Clinical Practice Guideline for Chronic Kidney Disease. Evaluation, classification and stratification. Am J Kidney Dis. 2002;39:S1–S266.

Bone RC, Balk RA, Cerra FB, Dellinger RP, Fein AM, Knaus WA, et al. Definitions for sepsis and organ failure and guidelines for the use of innovative therapies in sepsis: the ACCP/SCCM Consensus Conference Committee. American College of Chest Physicians/Society of Critical Care Medicine. Chest. 1992;101:1644–55.

Vincent JL, Moreno R, Takala J, Willatts S, De Mendonca A, Bruining H, et al. The SOFA (Sepsis-related Organ Failure Assessment) score to describe organ dysfunction/failure. On behalf of the Working Group on Sepsis-Related Problems of the European Society of Intensive Care Medicine. Intensive Care Med. 1996;22:707–10.

Brun-Buisson C, Meshaka P, Pinton P, Vallet B. EPISEPSIS: a reappraisal of the epidemiology and outcome of severe sepsis in French intensive care units. Intensive Care Med. 2004;30:580–8.

Sakr Y, Lobo SM, Moreno RP, Gerlach H, Ranieri VM, Michalopoulos A, et al. Patterns and early evolution of organ failure in the intensive care unit and their relation to outcome. Crit Care. 2012;16:R222.

Afessa B, Gajic O, Keegan MT. Severity of illness and organ failure assessment in adult intensive care units. Crit Care Clin. 2007;23:639–58.

Labarere J, Bertrand R, Fine MJ. How to derive and validate clinical prediction models for use in intensive care medicine. Intensive Care Med. 2014;40:513–27.

Steyerberg EW, Vickers AJ, Cook NR, Gerds T, Gonen M, Obuchowski N, et al. Assessing the performance of prediction models: a framework for traditional and novel measures. Epidemiology. 2010;21:128–38.

Little RJA, Rubin DB. Statistical analysis with missing data. 1st ed. New York: John Wiley; 1999.

Baldwin MR, Narain WR, Wunsch H, Schluger NW, Cooke JT, Maurer MS, et al. A prognostic model for 6-month mortality in elderly survivors of critical illness. Chest. 2013;143:910–9.

Osborn TM, Phillips G, Lemeshow S, Townsend S, Schorr CA, Levy MM, et al. Sepsis severity score: an internationally derived scoring system from the surviving sepsis campaign database*. Crit Care Med. 2014;42:1969–76.

Le Maguet P, Roquilly A, Lasocki S, Asehnoune K, Carise E, Saint Martin M, et al. Prevalence and impact of frailty on mortality in elderly ICU patients: a prospective, multicenter, observational study. Intensive Care Med. 2014;40:674–82.

National Institute for Health and Welfare. https://www.thl.fi/fi/web/kansantaudit/diabetes. Accessed 24 Nov 2014.

The Social Insurance Institution of Finland. http://www.kela.fi/laakkeet-ja-laakekorvaukset_laakekorvaustiedotteet. Accessed 24 Nov 2014.

Druml W, Metnitz B, Schaden E, Bauer P, Metnitz PG. Impact of body mass on incidence and prognosis of acute kideny injury requiring renal replacement therapy. Intensive Care Med. 2010;36:1221–8.

Ostermann M, Chang R, Riyadh ICU Program Users Group. Correlation between the AKI classification and outcome. Crit Care. 2008;12:R144.

Maccariello E, Rocha E, Valente C, Nogueira L, Rocha PT, Bonomo Jr H, et al. Effects of early changes in organ dysfunctions on the outcomes of critically ill patients in need of renal replacement therapy. Clinics. 2008;63:343–50.

Russell JA, Singer J, Bernard GR, Wheeler A, Fulkerson W, Hudson L, et al. Changing pattern of organ dysfunction in early human sepsis is related to mortality. Crit Care Med. 2000;28:3405–11.

Levy MM, Dellinger RP, Townsend SR, Linde-Zwirble WT, Marshall JC, Bion J, et al. The Surviving Sepsis Campaign: results of an international guideline-based performance improvement program targeting severe sepsis. Intensive Care Med. 2010;36:222–31.

Kaukonen KM, Bailey M, Suzuki S, Pilcher D, Bellomo R. Mortality related to severe sepsis and septic shock among critically ill patients in Australia and New Zealand, 2000–2012. JAMA. 2014;311:1308–16.

Royston P, Moons KG, Altman DG, Vergouwe Y. Prognosis and prognostic research: developing a prognostic model. BMJ. 2009;338:b604.

Vittinghoff E, McCulloch CE. Relaxing the rule of ten events per variable in logistic and Cox regression. Am J Epidemiol. 2007;165:710–8.

Acknowledgments

Written informed consent was obtained from the patients for publication of their individual details and accompanying images in this manuscript. The consent form is held by the authors’ institution and is available for review by the Editor-in-Chief.

We thank the Finnish Acute Kidney Injury (FINNAKI) Study Group: The FINNAKI study group: Central Finland Central Hospital: Raili Laru-Sompa, Anni Pulkkinen, Minna Saarelainen, Mikko Reilama, Sinikka Tolmunen, Ulla Rantalainen, Marja Miettinen. East Savo Central Hospital: Markku Suvela, Katrine Pesola, Pekka Saastamoinen, Sirpa Kauppinen. Helsinki University Central Hospital: Ville Pettilä, Kirsi-Maija Kaukonen, Anna-Maija Korhonen, Sara Nisula, Suvi Vaara, Raili Suojaranta-Ylinen, Leena Mildh, Mikko Haapio, Laura Nurminen, Sari Sutinen, Leena Pettilä, Helinä Laitinen, Heidi Syrjä, Kirsi Henttonen, Elina Lappi, Hillevi Boman. Jorvi Central Hospital: Tero Varpula, Päivi Porkka, Mirka Sivula Mira Rahkonen, Anne Tsurkka, Taina Nieminen, Niina Prittinen. Kanta-Häme Central Hospital: Ari Alaspää, Ville Salanto, Hanna Juntunen, Teija Sanisalo. Kuopio University Hospital: Ilkka Parviainen, Ari Uusaro, Esko Ruokonen, Stepani Bendel, Niina Rissanen, Maarit Lång, Sari Rahikainen, Saija Rissanen, Merja Ahonen, Elina Halonen, Eija Vaskelainen. Lapland Central Hospital: Meri Poukkanen, Esa Lintula, Sirpa Suominen. Länsi-Pohja Central Hospital: Jorma Heikkinen, Timo Lavander, Kirsi Heinonen, Anne-Mari Juopperi. Middle Ostrobothnia Central Hospital: Tadeusz Kaminski, Fiia Gäddnäs, Tuija Kuusela, Jane Roiko. North Karelia Central Hospital: Sari Karlsson, Matti Reinikainen, Tero Surakka, Helena Jyrkönen, Tanja Eiserbeck, Jaana Kallinen. Satakunta Hospital district: Vesa Lund, Päivi Tuominen, Pauliina Perkola, Riikka Tuominen, Marika Hietaranta, Satu Johansson. South Karelia Central Hospital: Seppo Hovilehto, Anne Kirsi, Pekka Tiainen, Tuija Myllärinen, Pirjo Leino, Anne Toropainen. Tampere University Hospital: Anne Kuitunen, Jyrki Tenhunen, Ilona Leppänen, Markus Levoranta, Sanna Hoppu, Jukka Sauranen, Atte Kukkurainen, Samuli Kortelainen, Simo Varila. Turku University Hospital: Outi Inkinen, Niina Koivuviita, Jutta Kotamäki, Anu Laine. Oulu University Hospital: Tero Ala-Kokko, Jouko Laurila, Sinikka Sälkiö. Vaasa Central Hospital: Simo-Pekka Koivisto, Raku Hautamäki, Maria Skinnar.

We thank Tieto Healthcare and Welfare for database management.

We received Clinical Research funding (EVO) from Helsinki University Hospital and from Lapland Central Hospital. The study was supported by the Sigrid Juselius Foundation, the Päivikki and Sakari Sohlberg Foundation, and the Finnish Society of Intensive Care. Dr Poukkanen received research grants from the Finnish Kidney Foundation and from the Finnish Society of Anaesthesiologists.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Consortia

Corresponding author

Additional information

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Authors’ contributions

MP drafted the manuscript, performed the statistical analyses and developed the initial models, and participated in study design and data gathering. SV helped to perform the statistical analyses and to develop the models, validated the models by bootstrapping method, critically revised the manuscript, and participated in study design and data gathering. MR critically revised the manuscript and participated in study design and data gathering. TS, biostatistician, M.Sc., performed a statistical review and revised the manuscript. SN, IP, JK, SK revised the manuscript and participated in the design and data gathering of the study. VP designed and coordinated the study and critically revised the manuscript. The FINNAKI-study Group members all participated in the local data gathering. All authors have read and approved the manuscript.

Additional files

Additional file 1:

A PDF file containing one picture. One-year survival of patients with early AKI.

Additional file 2:

A PDF file containing one table and text. The logistic regression equations for admission model and D3 model and equation of probability of death.

Rights and permissions

This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/. The Creative Commons Public Domain Dedication waiver (http://creativecommons.org/publicdomain/zero/1.0/) applies to the data made available in this article, unless otherwise stated in a credit line to the data.

About this article

Cite this article

Poukkanen, M., Vaara, S.T., Reinikainen, M. et al. Predicting one-year mortality of critically ill patients with early acute kidney injury: data from the prospective multicenter FINNAKI study. Crit Care 19, 125 (2015). https://doi.org/10.1186/s13054-015-0848-2

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/s13054-015-0848-2