Abstract

Background

The Australian Pancreatic Cancer Screening Program (APCSP) offers endoscopic ultrasound surveillance for individuals at increased risk of pancreatic ductal adenocarcinoma (PDAC) with all participants requiring assessment by a Familial Cancer Service before or after study enrolment.

Methods

Individuals aged 40–80 years (or 10 years younger than the earliest PDAC diagnosis) were eligible for APCSP study entry if they had 1) ≥ two blood relatives with PDAC (at least one of first-degree association); 2) a clinical or genetic diagnosis of Hereditary Pancreatitis or Peutz-Jeghers syndrome irrespective of PDAC family history; or 3) a known PDAC predisposition germline pathogenic variant (BRCA2, PALB2, CDKN2A, or Lynch syndrome) with ≥one PDAC-affected first- or second-degree relative.

Retrospective medical record review was conducted for APCSP participants enrolled at the participating Australian hospitals from January 2011 to December 2019. We audited the genetic investigations offered by multiple Familial Cancer Services who assessed APCSP participants according to national guidelines, local clinical protocol and/or the availability of external research-funded testing, and the subsequent findings. Descriptive statistical analysis was performed using Microsoft Excel.

Results

Of 189 kindreds (285 participants), 50 kindreds (71 participants) had a known germline pathogenic variant at enrolment (BRCA2 n = 35, PALB2 n = 6, CDKN2A n = 3, STK11 n = 3, PRSS1 n = 2, MLH1 n = 1). Forty-eight of 136 (35%) kindreds with no known germline pathogenic variant were offered mutation analysis; 89% was clinic-funded, with increasing self-funded testing since 2016. The relatively low rates of genetic testing performed reflects initial strict criteria for clinic-funded genetic testing. New germline pathogenic variants were detected in five kindreds (10.4%) after study enrolment (BRCA2 n = 3 kindreds, PALB2 n = 1, CDKN2A n = 1). Of note, only eight kindreds were reassessed by a Familial Cancer Service since enrolment, with a further 21 kindreds identified as being suitable for reassessment.

Conclusion

Germline pathogenic variants associated with PDAC were seen in 29.1% of our high-risk cohort (55/189 kindreds; 82/285 participants). Importantly, 10.4% of kindreds offered genetic testing were newly identified as having germline pathogenic variants, with majority being BRCA2. As genetic testing standards evolve rapidly in PDAC, 5-yearly reassessment of high-risk individuals by Familial Cancer Services is warranted.

Similar content being viewed by others

Background

Around 3600 new cases of pancreatic cancer (PC) were diagnosed in Australia in 2019 and the incidence is rising [1]. Approximately 95% of PC are pancreatic ductal adenocarcinomas (PDAC) [2]. PDAC has a poor prognosis as most patients present with advanced or metastatic disease [2]. Five-year survival rates are greatly influenced by the disease stage at the time of diagnosis [3].

Approximately 10% of PDAC clusters in families [4]. Eighty to 90% of familial PDAC cases do not yet have their genetic susceptibility identified [5]. However a family history of PDAC carries a 2.3 to 32-fold increased risk, depending upon the number of family members affected [5]. Familial pancreatic cancer (FPC) is defined as a family that contains at least two first-degree relatives affected by PDAC where the family history does not suggest a known cancer-predisposition syndrome, or where no causative germline pathogenic variant is identified [6]. Approximately 5–10% of patients with PDAC meet the criteria for FPC [7].

Only 10–20% of high-risk kindreds have a known heritable gene mutation [8,9,10] with the majority due to germline pathogenic variants in BRCA1 [11, 12], BRCA2 [12,13,14], CDKN2A [15], the mismatch repair genes (MLH1, MSH2, MSH6, PMS2), [8, 16, 17], Hereditary Pancreatitis genes [18] (SPINK1, PRSS1), STK11 [19], and TP53 [17, 20]. More recently, PALB2 [21] and ATM [10] germline pathogenic variants have been identified in 3–5% of familial PDAC cases.

BRCA2 germline pathogenic variants are found in 3.5 to 17% of families with PDAC [8, 12, 13] with the BRCA2 c.5946del Jewish Founder Mutation enriched in cohorts with significant Ashkenazi Jewish ancestry [22,23,24]. However, the penetrance of PDAC in those with BRCA2 germline pathogenic variants is low, with 95% of carriers not developing PDAC during their lifetime [25]. ATM germline pathogenic variants are the next most prevalent, present in 2–3% of PDAC families [26] but the PDAC penetrance is less clear. Other relevant germline pathogenic variants are less common and found in ≤1% of affected kindreds [27]. Although rare, Peutz-Jeghers syndrome (caused by germline pathogenic variants in STK11) has the highest associated cumulative lifetime PDAC risk of 36% [19]. Those with CDKN2A germline pathogenic variants have up to a 17% lifetime risk [28].

Recent studies of germline pathogenic variants in individuals with PDAC unselected for family history, age or other high-risk features have demonstrated a 3.5 to 13% germline mutation detection rate in established PDAC-associated genes [10, 27, 29,30,31,32]. This is particularly relevant as traditional family and personal history criteria can miss germline pathogenic variants in PDAC patients [10, 27, 33]. Based on this accumulating evidence, American Society of Clinical Oncology (ASCO) guidelines recommend consideration of germline genetic testing in all individuals diagnosed with PDAC [34]. Identifying a germline pathogenic variant in PDAC is important as it may allow targeted therapies such as Poly ADP-ribose polymerase (PARP) inhibitors in those with BRCA1/BRCA2 pathogenic variants [35, 36] and immunotherapy in Lynch syndrome [37]. Additional benefits include consideration of second primary cancer risk in survivors and identification of ‘at-risk’ relatives who may then seek appropriate surveillance.

PC screening with endoscopic ultrasound (EUS) and magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) in high-risk individuals can potentially reduce mortality by detecting PDAC at an earlier stage or its precursor lesions [38,39,40,41,42]. The average lifetime risk of developing PDAC is too low to advocate population screening [41], therefore the identification of high-risk individuals is key to ensuring PC screening is targeted to those who may derive the greatest benefit. Genetic information can help identify suitable high-risk individuals and can help personalise PC surveillance (e.g. individuals with Peutz-Jeghers syndrome commencing surveillance at a younger age) [41]. As a result of the growing importance of genetics, the American College of Gastroenterology recommends that genetic counselling be standard of care for individuals entering PC screening programs [40].

Given the continued controversy about the clinical utility and cost-effectiveness of PC screening, screening should only be performed in a research setting in specialised clinical centres, in line with Cancer of the Pancreas Surveillance (CAPS) consortium recommendations [41]. The Australian Pancreatic Cancer Screening Program (APCSP) is a research program that offers EUS and MRI surveillance for individuals at increased risk of developing PDAC. All high-risk individuals require mandatory assessment by a Familial Cancer Service as part of study participation. This provides us with a unique opportunity to describe the familial characteristics as well as the genetic testing pathways and outcomes of a high-risk cohort in the Australian context.

Method

The aim of this study was to summarise the familial characteristics and genetic testing outcomes of high-risk individuals and kindreds participating in the APCSP.

Recruitment

The APCSP commenced at St Vincent’s Hospital, Sydney in 2011 and at Austin Health, Melbourne in 2015. The study received institutional ethics approval at both sites (Approval numbers 10/055 and H2013/04954). Recruitment of high-risk individuals was possible via multiple pathways and was described in detail previously [43]. All participants provided written informed consent.

All participants were assessed to determine eligibility by the clinical research coordinator before enrolment. Individuals aged 40–80 years (or 10 years younger than the earliest PDAC diagnosis in the family), who met one of the following criteria were eligible for study entry: 1) two or more blood relatives with PDAC (including at least one of first-degree association); 2) a clinical or genetic diagnosis of Hereditary Pancreatitis or Peutz-Jeghers syndrome irrespective of PDAC family history; or 3) carrier of a known PDAC predisposition germline pathogenic variant (BRCA2, PALB2, CDKN2A, or Lynch syndrome (MLH1, PMS2, MSH6, MSH2 or EPCAM deletion)) with at least one PDAC-affected first- or second-degree relative.

Genetic counselling and testing

Prerequisite formal genetic counselling was completed either before or after screening program enrolment. Individuals meeting FPC criteria who had not completed genetic counselling prior to enrolment were referred to a Familial Cancer Service for assessment before their EUS. If clinically indicated, genetic testing was offered to either the screening trial participant or their close affected relative. National Australian guidelines and clinical protocols to determine eligibility for clinic-funded testing were applied, which varied over time, but initially required a greater than 10% likelihood of identifying a germline pathogenic variant or the presence of a germline pathogenic variant in a biological relative. Those not eligible for clinic-funded testing were able to consider self-funded genetic testing. Some individuals underwent external research-funded genetic testing, independent of the screening program, if the Familial Cancer Service identified that they met inclusion criteria.

The decision to facilitate genetic testing was made on an individual basis and included any genetic investigation for an inherited cancer predisposition syndrome, such as immunohistochemistry of the mismatch repair proteins (MMR IHC) or mutation analysis (e.g. Jewish Founder Mutation screen; predictive testing; single gene, gene panel or whole exome sequencing (WES)). Research results were confirmed in a National Association of Testing Authorities (NATA), Australia authorised laboratory. All clinical genetic testing was performed in accredited Australian or international clinical laboratories. All reported genetic test results were confirmed by acquisition of clinical test reports from the appropriate Familial Cancer Service.

Data analysis

Data from participants enrolled at St Vincent’s Hospital, Sydney from January 2011 to December 2019 and at Austin Health, Melbourne from January 2015 to December 2019 were included in the current analysis. All participants were required to complete a detailed baseline personal and family health history questionnaire. Participant reported family history was cross-checked with clinical correspondence and de-identified pedigrees provided by the Familial Cancer Service. Confirmation of PDAC diagnosis was obtained through verification of pathology reports, death certificates or cancer registry databases with reported family history corroborated by multiple relatives in unconfirmed cases. Genetic testing is reported for either the participant (if tested) or their affected relative (if uninformative), with the findings updated as new germline pathogenic variants were identified. Descriptive statistical analysis was performed using Microsoft Excel. Key case vignettes have been included to demonstrate genetic testing approaches and family outcomes of newly-identified germline pathogenic variants.

Results

Participant demographics

Two-hundred and eighty-five participants, comprising 189 kindreds, enrolled in the APCSP had completed genetic counselling through a Familial Cancer Service at the time of analysis. Participant demographics are summarised in Table 1. Participant family history demographics were updated to account for any new PC diagnoses detected through screening at the time of analysis (n = 11 participants, three kindreds).

Genetic investigations and prerequisite genetic counselling

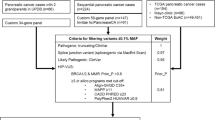

The genetic testing pathway for all study participants is depicted in a consort diagram (Fig. 1). At the time of screening program enrolment, 70/285 (24.6%) participants from 50/189 (26.5% kindreds) were identified as a germline pathogenic variant carrier for a known PDAC susceptibility gene and one participant had a clinical diagnosis of Peutz-Jeghers syndrome but declined genetic testing. Additionally, three kindreds (n = 2 participants; n = 1 affected first-degree relative) had a variant of uncertain significance in a known PDAC susceptibility gene (Fig. 1) had a clinical diagnosis of Peutz-Jeghers syndrome but declined genetic testing. Additionally, three kindreds (n = 2 participants; n = 1 affected first-degree relative) had a variant of uncertain significance in a known PDAC susceptibility gene (Fig. 1).

Of the 136 kindreds with no known germline pathogenic variant at enrolment, 52 were offered genetic testing (either clinic, external research or self-funded) during their genetics consultation. At least one individual from 48 kindreds proceeded, however, three unaffected participants declined self-funded testing and one kindred declined clinic-funded testing on an affected first-degree relative’s stored DNA. The type of investigation, individual tested and funding source for the 48 kindreds that proceeded with mutation analysis are shown in Fig. 2. In six of these kindreds, updated testing was performed due to a new diagnosis; in response to a relative’s genetic test result or the family was reviewed when a younger relative enrolled in the study.

Clinic-funded MMR IHC to evaluate the likelihood of Lynch syndrome was arranged for 17 kindreds. All specimens showed preserved staining. This was the only investigation offered for nine kindreds, with the remaining eight kindreds undergoing additional mutation analysis (Fig. 3). DNA from a close affected relative for an additional four kindreds was stored without initiation of mutation analysis. An affected relative for one kindred was offered testing but died prior to blood collection. Genetic investigations performed in three participants unrelated to the PDAC family history (e.g. negative predictive test from maternal side when paternal family history meets FPC criteria) were excluded from analysis. Mutation analysis was performed for at least one individual in 100/189 (52.9%) kindreds. In some cases, mutation analysis was performed for an affected or unaffected relative (30 and 1 kindreds, respectively) rather than the screening participant themselves. However, one or more screening participant(s) from the remaining 69 kindreds directly underwent mutation analysis.

The funding source for mutation analysis in the 100 tested kindreds (n = 166 participants) is shown in Fig. 4. Eighty-nine kindreds (n = 151 participants) had clinic-funded genetic testing, seven kindreds (n = 7 participants) had self-funded testing and four kindreds (n = 8 participants) underwent external research-funded testing. Unsurprisingly, self-funded testing was only observed since 2016 (seven kindreds).

Interestingly, new germline pathogenic variants (Class 4 or 5) were detected in 5/48 (10.4%) kindreds (n = 3 BRCA2; n = 1 PALB2; n = 1 CDKN2A). In addition, one participant had a newly identified PALB2 variant of uncertain significance. Three participants (from three separate kindreds) at 50% risk of a newly-identified germline pathogenic variant had not undergone predictive testing at the time of analysis. The complete cohort of participants and kindreds with a germline pathogenic variant is shown in Table 2. The germline pathogenic variant status of all tested participants is summarised in Figs. 5 and 6.

Overall, 119 participants (88 kindreds) did not undergo any mutation analysis despite meeting FPC criteria, typically as no affected relative was available to test. These participants were seen when Australian national consensus guidelines excluded unaffected individuals from clinic-funded genetic testing. At the time of analysis, 23 individuals from eight kindreds have undergone Familial Cancer Service reassessment (Table 3). A further 21/134 (16%) untested FPC kindreds may be suitable for Familial Cancer Service reassessment due to recent changes in clinical practice and the relevant services have been notified by the authors Table 4).

Case vignettes

Discussion

Two hundred and eighty-five high-risk individuals from 189 kindreds participating in the APCSP have undergone mandatory Familial Cancer Service assessment. This is one of the largest PC screening cohorts to have undergone formal genetic counselling, only surpassed by screening studies conducted in countries or regions with a significantly larger population size than Australia [38, 44, 45].

In our study, around 25% of participants (n = 71) from 50 kindreds had a known germline pathogenic variant or clinical diagnosis at the time of study enrolment. In addition, 92 participants from 48 kindreds underwent genetic testing after study enrolment. Eight participants from five kindreds were found to have a germline pathogenic variant (n = 5 BRCA2, n = 2 PALB2, n = 1 CDKN2A). Three additional participants are at 50% risk of a newly-identified familial germline pathogenic variant but have not yet undergone predictive testing (n = 2 BRCA2; n = 1 PALB2). This is a significant detection rate of new germline pathogenic variants in 10.4% of kindreds after study enrolment.

One hundred and nineteen participants from 88 kindreds were not offered genetic testing. For most FPC kindreds this was due to the lack of a suitable person to test and/or because no stored DNA from an affected relative was available. This highlights the importance of facilitating genetic testing at the time of PDAC diagnosis. As previously detailed, studies have shown a significant proportion of PDAC patients have a germline pathogenic variant detected, irrespective of family history or age of diagnosis. When age, family history and Ashkenazi Jewish ancestry are considered, this proportion increases. These findings support the recent ASCO guidelines that those with PDAC be referred for genetic counselling, especially if diagnosed < 60 years of age, have Ashkenazi Jewish ancestry, have a family history of PDAC, a personal or family history of other cancers (particularly breast, ovarian, stomach, bowel and melanoma) and a personal or family history of pancreatitis.

A heritable syndrome cannot be discounted in those without these features. Furthermore, as the cost of genetic testing continues to drop significantly, self-funded genetic testing is increasingly within reach for many patients who may wish to pursue this option given the therapeutic and familial implications. This is demonstrated by the increase in self-funded testing uptake in our cohort within the last five years. As PDAC can unfortunately be associated with rapid deterioration for some, DNA storage should be considered in all. As highlighted in case vignette 1, family members who wish to pursue genetic testing in the future will benefit from an affected relatives’ stored DNA. Increasingly, somatic testing is being arranged by physicians to guide patient therapy. Unfortunately, somatic testing is not adequate for reliable detection of germline pathogenic variants, therefore paired germline testing should be considered [17].

Although genetic testing in the affected individual would be ideal, this is not always feasible. Cremin et al. 2020 [30] noted that when prospective genetic testing for unselected patients with PDAC was offered in British Columbia, Canada, 12.8% (n = 39) PDAC patients died before genetic testing could be offered or performed, and overall, only 59.2% (n = 177/299) of all referred index patients completed testing despite the presence of efficient testing protocols and the availability of telehealth services. PDAC-related morbidity, mortality and logistic/travel challenges have all been cited in the literature as barriers [46]. Consideration of DNA storage for affected individuals or genetic testing on tumour tissues may offer other avenues of identifying germline pathogenic variants in patients with FPC histories.

A proportion of FPC kindreds in our cohort were not offered genetic testing after Familial Cancer Service review as they did not have a family history characteristic of a heritable cancer syndrome. Of note, at the time of our analysis, there were no national guidelines to offer testing to PDAC affected individuals apart from those with features of an inherited cancer syndrome. In some families current testing criteria may miss relevant germline pathogenic variants [33]. To the authors’ knowledge, only eight kindreds have undergone a subsequent genetics review since the time of their initial Familial Cancer Service assessment. As all participant information was reviewed during this analysis, a further 21/134 kindreds (16%) were identified where additional clinic-funded genetic testing should be considered. Our previous published data indicates that 89% of participants are interested in genetics review as new information becomes available and 80% of untested participants reported wanting to undergo genetic testing [43]. Since testing guidelines are changing rapidly, we highlight the importance of periodic case review of FPC kindreds. At minimum, this would entail updating the family history to record any new cancer diagnoses, reviewing participant genetic testing status and suitability for clinical and/or expanded testing, and an updated discussion about inherited and environmental risks.

As demonstrated in case vignette 1, at initial presentation, the family were assessed to have less than 10% chance of finding a germline pathogenic variant and initially declined self-funded testing. By today’s criteria, the family would likely be offered clinic-funded testing based on their family history. Critically almost half (46.6%) of kindreds in our high-risk screening cohort have not undergone genetic testing. With evidence of unexpected findings accumulating, review of these individuals and consideration of testing where appropriate is warranted.

Notably, of the 48 uninformative kindreds tested so far, only one variant of uncertain significance was identified. All germline pathogenic variants identified were relevant to PDAC. This reflects the strength of the selectivity of the Familial Cancer Services when offering genetic testing in the past. Broadening the criteria to reduce the chance of missing a relevant germline pathogenic variant needs to be balanced against identifying a variant of uncertain significance or a germline pathogenic variant in a less well-established PDAC gene and the significant uncertainty this can generate for individuals and their families [30, 45].

Limitations

Our study had predominantly Caucasian participants and therefore our findings cannot readily be translated to other ethnic groups. Enrolment in the APCSP first commenced in 2011 with some participants completing genetic counselling many years prior to program enrolment. Therefore, genetic investigations in our cohort occurred over a period of over 20 years as new participants were recruited into the study. The variability in testing performed likely represents the diversity in family histories, in addition to significant changes in testing costs, guidelines and the considerable changes in practice that have occurred over time. Of note, there has been a dramatic increase in the availability of genetic testing options in Australia since 2011, particularly the availability of self-funded testing and broader gene panel testing. However, this is also a relative strength of our study as it reflects real-world experience and the ongoing evolution of standard of care in genetics.

Conclusion

Germline pathogenic variants associated with PDAC were seen in 29.1% of our high-risk cohort (55/189 kindreds or 82/285 participants). Of these, 5 of 48 (10.4%) kindreds offered mutation analysis were newly-identified to have a germline pathogenic variant after study enrolment. Therefore, in a subset of participants enriched for a family history of PDAC, the rate of new germline pathogenic variants detected was high with BRCA2 being the most represented. Updated and new gene panel testing should be considered in selected high-risk individuals undergoing PC screening. There are benefits to screening programs periodically analysing their data and rereferral to a Familial Cancer Service should be considered for FPC families who last consulted a genetics service over 5 years ago. A significant proportion of our cohort (29/139 (21%) kindreds) already underwent or would benefit from reassessment by a genetics service. A Familial Cancer Service referral for all newly diagnosed individuals with PDAC should be considered with DNA storage discussed early in their clinical course. The option of treatment-focused and/or self-funded genetic testing should also be discussed as this may help improve clinical outcomes for individuals affected by PDAC and their families.

Availability of data and materials

The datasets generated and/or analysed during the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

Change history

08 September 2021

A Correction to this paper has been published: https://doi.org/10.1186/s13053-021-00195-w

Abbreviations

- APCSP:

-

Australian Pancreatic Screening Program

- ASCO:

-

American Society of Clinical Oncology

- BCC:

-

Basal cell carcinoma

- BOADICEA:

-

Breast and Ovarian Analysis of Disease Incidence and Carrier Estimation Algorithm

- CAPS:

-

Cancer of the Pancreas Surveillance

- CRC:

-

Colorectal cancer

- DCIS:

-

Ductal carcinoma in situ

- EUS:

-

Endoscopic ultrasound

- FDR:

-

First-degree relative

- FPC:

-

Familial pancreatic cancer

- GPV:

-

Germline pathogenic variant

- JFM:

-

Jewish Founder Mutation

- MMR IHC:

-

Immunohistochemistry of the mismatch repair proteins

- MRI:

-

Magnetic resonance imaging

- NATA:

-

National Association of Testing Authorities

- PARP:

-

Poly ADP-ribose polymerase

- PC:

-

Pancreatic cancer

- PDAC:

-

Pancreatic ductal adenocarcinoma

- pNET:

-

pancreatic neuroendocrine tumour

- RCC:

-

Renal cell carcinoma

- SCC:

-

Squamous cell carcinoma

- SDR:

-

Second-degree relative

- TDR:

-

Third-degree relative

- VUS:

-

Variant of uncertain significance

- WES:

-

Whole exome sequencing

References

Australian Institute of Health and Welfare. A summary of incidence, mortality, survival and prevalence of cancer in Australia. Cancer Data in Australia. 2020. Available from: https://www.aihw.gov.au/reports/cancer/cancer-data-in-australia/contents/cancer-summary-data-visualisation. Accessed 21st November 2020. Last updated 13th November 2020.

Ducreux M, Cuhna AS, Caramella C, Hollebecque A, Burtin P, Goéré D, et al. Cancer of the pancreas: ESMO Clinical Practice Guidelines for diagnosis, treatment and follow-up. Ann Oncol. 2015;26(Supplement 5):v56–68. https://doi.org/10.1093/annonc/mdv295.

Furukawa H, Okada S, Saisho H, Ariyama J, Karasawa E, Nakaizumi A. Clinicopathologic Features of Small Pancreatic. Cancer. 1996;78(5):986–90 DOI: 10.1002/(SICI)1097-0142(19960901)78:5<986::AID-CNCR7>3.0.CO;2-A.

Permuth-Wey J, Egan KM. Family history is a significant risk factor for pancreatic cancer: Results from a systematic review and meta-analysis. Fam Cancer. 2009;8(2):109–17.[PMID: 18763055. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10689-008-9214-8.

Klein AP, Brune KA, Petersen GM, Goggins M, Tersmette AC, Offerhaus GJA, et al. Prospective Risk of Pancreatic Cancer in Familial Pancreatic Cancer Kindreds. Cancer Res. 2004;64(7):2634–8.[PMID: 15059921. https://doi.org/10.1158/0008-5472.can-03-3823.

Klein AP. Identifying people at a high risk of developing pancreatic cancer. Nat Rev Cancer. 2013;13(1):66–74.[PMID: 23222481. https://doi.org/10.1038/nrc3420.

Petersen GM. Familial Pancreatic Cancer. Semin Oncol. 2016;43(5):548–3.[PMID: 27899186. https://doi.org/10.1053/j.seminoncol.2016.09.002.

Chaffee KG, Oberg AL, McWilliams RR, Majithia N, Allen BA, Kidd J, et al. Prevalence of Germline Mutations in Cancer Genes. Genet Med. 2018;20(1):119–27. [PMID: 28726808. https://doi.org/10.1038/gim.2017.85.

Roberts NJ, Norris AL, Petersen GM, Bondy ML, Gallinger S, Kurtz RC, et al. Whole genome sequencing defines the genetic heterogeneity of familial pancreatic cancer. 2016;6(2):166–175. [DOI: https://doi.org/10.1158/2159-8290.CD-15-0402].

Grant RC, Selander I, Connor AA, Selvarajah S, Borgida A, Briollais L, et al. Prevalence of germline mutations in cancer predisposition genes in patients with pancreatic cancer. Gastroenterology. 2015;148(3):556–64 Available from: http://dx.doi.org/10.1053/j.gastro.2014.11.042 [PMID: 25479140 DOI: 10.1053/j.gastro.2014.11.042].

Al-Sukhni W, Rothenmund H, Eppel Borgida A, Zogopoulos G, O’Shea AM, Pollett A, et al. Germline BRCA1 mutations predispose to pancreatic adenocarcinoma. Hum Genet. 2008;124(3):271–8.[PMID: 18762988. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00439-008-0554-0.

Zhen DB, Rabe KG, Gallinger S, Syngal S, Schwartz AG, Goggins MG, et al. BRCA1, BRCA2, PALB2, and CDKN2A mutations in familial pancreatic cancer: A PACGENE study. Genet Med. 2015;17(7):569–77.[PMID: 25356972. https://doi.org/10.1038/gim.2014.153.

Murphy KM, Brune KA, Griffin C, Sollenberger JE, Petersen GM, Bansal R, et al. Evaluation of candidate genes MAP 2K4, MADH4, ACVR1B, and BRCA2 in familial pancreatic cancer: Deleterious BRCA2 mutations in 17%. Cancer Res. 2002;62(13):3789–93 PMID: 12097290.

Moran A, O’Hara C, Khan S, Shack L, Woodward E, Maher ER, et al. Risk of cancer other than breast or ovarian in individuals with BRCA1 and BRCA2 mutations. Fam Cancer. 2012;11(2):235–42.[PMID: 22187320. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10689-011-9506-2.

McWilliams RR, Wieben ED, Rabe KG, Pedersen KS, Wu Y, Sicotte H, et al. Prevalence of CDKN2A mutations in pancreatic cancer patients: Implications or genetic counseling. Eur J Hum Genet. 2011;19(4):472–8.[PMID: 21150883. https://doi.org/10.1038/ejhg.2010.198.

Kastrinos F, Mukherjee B, Tayob N, Wang F, Sparr J, Raymond VM, et al. Risk of pancreatic cancer in families with Lynch syndrome. JAMA. 2009;302(16):1790–5.[PMID: 19861671. https://doi.org/10.1001/jama.2009.1529.

Yurgelun MB, Chittenden AB, Morales-Oyarvide V, Rubinson DA, Dunne RF, Kozak MM, et al. Germline cancer susceptibility gene variants, somatic second hits, and survival outcomes in patients with resected pancreatic cancer. Genet Med. 2019;21(1):213–23. [PMID: 29961768. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41436-018-0009-5.

LaRusch J, Whitcomb DC. Genetics of pancreatitis. Curr Opin Gastoenterol. 2011;27(5):467–74. [PMID: 21844754. https://doi.org/10.1097/MOG.0b013e328349e2f8.

Giardiello FM, Brensinger JD, Tersmette AC, Goodman SN, Petersen GM, Booker SV, et al. Very high risk of cancer in familial Peutz-Jeghers syndrome. Gastroenterology. 2000;119(6):1447–53.[PMID: 11113065. https://doi.org/10.1053/gast.2000.20228.

Ruijs MWG, Verhoef S, Rookus MA, Pruntel R, Van Der Hout AH, Hogervorst FBL, et al. TP53 germline mutation testing in 180 families suspected of Li-Fraumeni syndrome: Mutation detection rate and relative frequency of cancers in different familial phenotypes. J Med Genet. 2010;47(6):421–8. [PMID: 20522432. https://doi.org/10.1136/jmg.2009.073429.

Jones S, Hruban RH, Kamiyama M, Borges M, Zhang X, Parsons W, et al. Exomic Sequencing Identifies PALB2 as a Pancreatic Cancer Susceptibility Gene. Science. 2010;324(5924). https://doi.org/10.1126/science.1171202.

Salo-Mullen EE, O’Reilly EM, Kelsen DP, Ashraf AM, Lowery MA, Yu KH, et al. Identification of germline genetic mutations in patients with pancreatic cancer. Cancer. 2015;121(24):4382–8.[PMID: 26440929. https://doi.org/10.1002/cncr.29664.

Lowenfels A, Maisonneuve P. Pancreatitis and the risk of pancreatic cancer. N Engl J Med. 1993;329(14):977–86. [PMID: 847946. https://doi.org/10.1056/NEJM199305203282001.

Figer A, Irmin L, Geva R, Flex D, Sulkes J, Sulkes A, et al. The rate of the 6174delT founder Jewish mutation in BRCA2 patients with non-colonic gastrointestinal tract tumours in Israel, vol. 84; 2001. p. 478–81.[PMID: 11207041. https://doi.org/10.1054/bjoc.2000.1605.

Goggins M, Sehutte M, Lu J, Moskaluk CA, Weinstein CL, Petersen GM, et al. Germline BRCA2 gene mutations in patients with apparently sporadic pancreatic carcinomas. Cancer Res. 1996;56(23):5360–4.

Roberts NJ, Jiao Y, Yu J, Kopelovich L, Petersen GM, Bondy ML, et al. ATM mutations in patients with hereditary pancreatic cancer. Cancer Discov. 2012;2(1):41–6. https://doi.org/10.1158/2159-8290.CD-11-0194.

Shindo K, Yu J, Suenaga M, Fesharakizadeh S, Cho C, Macgregor-Das A, et al. Deleterious germline mutations in patients with apparently sporadic pancreatic adenocarcinoma. J Clin Oncol. 2017;35(30):3382–90. https://doi.org/10.1200/JCO.2017.72.3502.

Vasen HFA, Gruis NA, Frants RR, Van Der Velden PA, Hille ETM, Bergman W. Risk of developing pancreatic cancer in families with familial atypical multiple mole melanoma associated with a specific 19 deletion of p16 (p16-Leiden). Int J Cancer. 2000;87(6):809–11. https://doi.org/10.1002/1097-0215(20000915)87:6<809::AID-IJC8>3.0.CO;2-U.

Brand R, Borazanci E, Speare V, Dudley B, Karloski E, Peters MLB, et al. Prospective study of germline genetic testing in incident cases of pancreatic adenocarcinoma. Cancer. 2018;124(17):3520–7. https://doi.org/10.1002/cncr.31628.

Cremin C, Lee MKC, Hong Q, Hoeschen C, Mackenzie A, Dixon K, et al. Burden of hereditary cancer susceptibility in unselected patients with pancreatic ductal adenocarcinoma referred for germline screening. Cancer Med. 2020;9(11):4004–13. https://doi.org/10.1002/cam4.2973.

Hu C, LaDuca H, Shimelis H, Polley EC, Lilyquist J, Hart SN, et al. Multigene Hereditary Cancer Panels Reveal High-Risk Pancreatic Cancer Susceptibility Genes. JCO Precis Oncol. 2018;(2):1–28. https://doi.org/10.1200/PO.17.00291.

Hu C, Hart SN, Bamlet WR, Moore RM, Nandakumar K, Eckloff BW, et al. Prevalence of pathogenic mutations in cancer predisposition genes among pancreatic cancer patients. Cancer Epidemiol Biomarkers Prev. 2016;25(1):207–11. https://doi.org/10.1158/1055-9965.EPI-15-0455.

Lowery MA, Wong W, Jordan EJ, Lee JW, Kemel Y, Vijai J, et al. Prospective evaluation of germline alterations in patients with exocrine pancreatic neoplasms. J Natl Cancer Inst. 2018;110(10):1067–74. https://doi.org/10.1093/jnci/djy024.

Stoffel EM, McKernin SE, Brand R, Canto M, Goggins M, Moravek C, et al. Evaluating susceptibility to pancreatic cancer: ASCO provisional clinical opinion. J Clin Oncol. 2019;37(2):153–64. https://doi.org/10.1200/JCO.18.01489.

Golan T, Hammel P, Reni M, Van Cutsem E, Macarulla T, Hall MJ, et al. Maintenance olaparib for germline BRCA-mutated metastatic pancreatic cancer. N Engl J Med. 2019;381(4):317–27. https://doi.org/10.1056/NEJMoa1903387.

Christenson ES, Jaffee E, Azad NS. Current and emerging therapies for patients with advanced pancreatic ductal adenocarcinoma: a bright future. Lancet Oncol. 2020;21(3):e135–45. https://doi.org/10.1016/S1470-2045(19)30795-8.

Sohal DPS, Kennedy EB, Cinar P, Conroy T, Copur MS, Crane CH, et al. Metastatic Pancreatic Cancer: ASCO Guideline Update. J Clin Oncol. 2020:JCO2001364. https://doi.org/10.1200/JCO.20.01364.

Vasen H, Ibrahim I, Robbers K, Van Mil AM, Potjer T, Bonsing BA, et al. Benefit of surveillance for pancreatic cancer in high-risk individuals: Outcome of long-term prospective follow-up studies from three European expert centers. J Clin Oncol. 2016;34(17):2010–9. https://doi.org/10.1200/JCO.2015.64.0730.

Canto MI, Hruban RH, Fishman EK, Kamel IR, Schulick R, Zhang Z, et al. Frequent detection of pancreatic lesions in asymptomatic high-risk individuals. Gastroenterology. 2012;142(4):796–804. https://doi.org/10.1053/j.gastro.2012.01.005.

Aslanian HR, Lee JH, Canto MI. Journal Pre-proof AGA Clinical Practice Update on Pancreas Cancer Screening in High Risk Individuals: Expert Review. Gastroenterology. 2020; 159(1):358–362 [DOI: https://doi.org/10.1053/j.gastro.2020.03.088].

Goggins M, Overbeek KA, Brand R, Syngal S, Del Chiaro M, Bartsch DK, et al. Management of patients with increased risk for familial pancreatic cancer: updated recommendations from the International Cancer of the Pancreas Screening (CAPS) Consortium. Gut. 2020;69(1):7–17. https://doi.org/10.1136/gutjnl-2019-319352.

Pereira SP, Oldfield L, Ney A, Hart PA, Keane MG, Pandol SJ, et al. Early detection of pancreatic cancer. Lancet Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2020;5(7):698–710. https://doi.org/10.1016/S2468-1253(19)30416-9.

Dwarte T, McKay S, Johns A, Tucker K, Spigelman AD, Williams D, et al. Genetic counselling and personalised risk assessment in the Australian pancreatic cancer screening program. Hered Cancer Clin Pract. 2019;17(1):1–14. https://doi.org/10.1186/s13053-019-0129-1.

Schneider R, Slater EP, Sina M, Habbe N, Fendrich V, Matthäi E, et al. German national case collection for familial pancreatic cancer (FaPaCa): Ten years experience. Fam Cancer. 2011;10(2):323–30. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10689-010-9414-x.

Abe T, Blackford AL, Tamura K, Ford M, McCormick P, Chuidian M, et al. Deleterious germline mutations are a risk factor for neoplastic progression among high-risk individuals undergoing pancreatic surveillance. J Clin Oncol. 2019;37(13):0–80. https://doi.org/10.1200/JCO.18.01512.

Walker EJ, Carnevale J, Pedley C, Blanco A, Chan S, Collisson EA, et al. Referral frequency, attrition rate, and outcomes of germline testing in patients with pancreatic adenocarcinoma. Fam Cancer. 2019;18(2):241–51. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10689-018-0106-2.

Acknowledgments

We would like to thank all participants, families and the Familial Cancer Services across Australia who have participated in a genetics assessment as part of this study. We would like to acknowledge Prof Andrew Biankin, Prof Anthony Gill and the Australian Pancreatic Cancer Genome Initiative network for their support and ongoing collaboration: http://pancreaticcancer.net.au/about-collaborators. A special thanks is also given to Dr. Lesley Andrews, A/Prof Judy Kirk and Dr. Marcia Canto for their contribution to the initial screening program development.

Funding

AFPaCC was enabled by a Cancer Institute NSW Translational Health Services Research Grant. The APGI is supported by The Avner Pancreatic Cancer Foundation. The Clinical Research Coordinator positions in both Sydney and Melbourne are currently supported by PanCare.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

KM reviewed data from the Austin Health cohort and drafted the Abstract, Background and Discussion sections of the manuscript. TD reviewed St Vincent’s Hospital cohort data, performed data analysis and prepared study figures/tables, and drafted the Methods and Results sections of the manuscript. MN established the screening program at Austin Health, performed screening and revised the final manuscript. KT contributed to the research design, assisted in participant recruitment, provided genetic counselling and revised the final manuscript. RBV performed screening and revised the final manuscript. ME performed screening and revised the final manuscript. AC maintained Austin Health cohort data and contributed to data review. ADS assisted in participant recruitment, provided genetic counselling and revised the final manuscript. LS provided genetic counselling, referred patients and revised the final manuscript. DBW contributed to the research design, performed screening and revised the final manuscript. MBD helped set up the study at Austin Health and facilitated genetic counselling. AJ contributed to the establishment of AFPaCC, prepared ethics documents and revised the final manuscript. TJ assisted with genetic counselling, manuscript conception and revision of final manuscript. AS designed and established the screening program in Australia; prepared documents for ethics submission, recruited patients, performed screening and revised all the draft of the manuscript and approved final version.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate

This study was approved by St Vincent’s Hospital Human Research Ethics Committee (Approval number 10/055) and Austin Health Human Research Ethics Committee (Approval number H2013/04954) and all procedures conducted were in accordance with the 1964 Helsinki declaration and its later amendments. Informed consent was obtained from all individual participants included in the study. This article does not contain any studies with animals performed by any of the authors.

Consent for publication

Participants provided consent for the publication of deidentified data.

Competing interests

The authors declare they have no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

The original version of this article was revised: Affiliation 6 has been corrected.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/. The Creative Commons Public Domain Dedication waiver (http://creativecommons.org/publicdomain/zero/1.0/) applies to the data made available in this article, unless otherwise stated in a credit line to the data.

About this article

Cite this article

Murali, K., Dwarte, T.M., Nikfarjam, M. et al. Significant detection of new germline pathogenic variants in Australian Pancreatic Cancer Screening Program participants. Hered Cancer Clin Pract 19, 33 (2021). https://doi.org/10.1186/s13053-021-00190-1

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/s13053-021-00190-1