Abstract

Background

Dilated cardiomyopathy (DCM) is an etiologically heterogeneous group of diseases of the myocardium. With the rapid evolution in laboratory investigations, genetic background is increasingly determined including many genes with variable penetrance and expressivity. Biallelic NEXN variants are rare in humans and associated with poor prognosis: fetal and perinatal death or severe DCMs in infants.

Case presentation

We describe two male infants with prenatal diagnosis of dilated cardiomyopathy with impaired ventricular contractility. One of the patients showed hydrops and polyhydramnios. Postnatally, a DCM with severely reduced systolic function was confirmed and required medical treatment. In patient 1, Whole Exome Sequencing (WES) revealed a homozygous NEXN variant: c.1156dup (p.Met386fs) while in patient 2 a custom Next Generation Sequencing (NGS) panel revealed the homozygous NEXN variant c.1579_1584delp. (Glu527_Glu528del). These NEXN variants have not been previously described. Unlike the unfavorable prognosis described for biallelic NEXN variants, we observed in both our patients a favorable clinical course over time.

Conclusion

This report might help to broaden the present knowledge regarding NEXN biallelic variants and their clinical expression. It might be worthy to consider the inclusion of the NEXN gene sequencing in the investigation of pediatric patients with DCM.

Similar content being viewed by others

Background

Cardiomyopathies (CMPs) are a heterogeneous group of diseases of the myocardium accounting for the majority of Heart Failure (HF). The most frequent CMPs in adult population are Dilated cardiomyopathy (DCM), whose estimated prevalence varies from 1 in 250 to 1 in 500, and Hypertrophic cardiomyopathy (HCM), ranging from 1 in 500 to 1 in 5000 [1].

Unlike adult population, pediatric CMP is a rare condition that may lead to poor outcomes: nearly 40% of children who present with symptomatic CMP undergo heart transplantation or die within the first 2 years after diagnosis [2].

Pediatric CMP can be an isolated entity or part of complex multisystemic context. Specific cardiac and extracardiac workup must be dedicated to children with CMP due to increased percentage of complex conditions compared to adult onset CMP [3].

Among possible etiologies, genetically determined forms have been increasingly recognized and in recent years significant efforts have been made to unravel the underlying genes: linkage analyses and candidate gene sequencing in familial cases, as well as genome-wide association studies in large cohorts, have contributed to the identification of risk alleles and disease-causing variants, many of which encode for structural components of the cardiac muscle, such as the sarcomere or the cardiac z-disc [4].

NEXN encodes the nexilin, an essential protein for Z-disk stability [5, 6]. Few heterozygous pathogenic variants in NEXN were found in large cohorts of idiopathic DCM [4] patients and others were reported in pedigrees affected by HCM and their families [7].

The prognosis appears to be worse in those rare individuals carrying biallelic NEXN pathogenic variants (either homozygous or compound heterozygous), who usually do not survive childhood [8, 9] or present with lethal form of fetal CMP [10]. We report on two unrelated pediatric cases of NEXN-associated CMP, due to biallelic variants, with prolonged survival.

Case presentation

Case 1

Patient 1 (P1) was diagnosed with CMP prenatally at 24 weeks of gestation, when the mother (a 38-year-old Egyptian woman) was referred for polyhydramnios, hydrops and severely reduced fetal biventricular systolic function and left ventricular (LV) dilation. Family history revealed parents to be 3rd -degree cousins whereas obstetric history was remarkable for two first-trimester miscarriages and two intrauterine deaths in the late second trimester; the couple also had three healthy children currently in their teens.

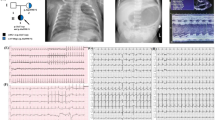

Prenatal ultrasound examination found no evidence of cardiac or extracardiac structural anomalies or sustained arrhythmia to explain myocardial dysfunction; screening for congenital infections (TORCH, Parvovirus, Adenovirus, Coxsackie) was negative except for SARS-CoV-2 IgG and IgM antibodies from an asymptomatic infection. Karyotyping and array-CGH were both normal. The child was born at 34 + 4 weeks of GA by urgent cesarean section, weighing 3240 g (99th percentile). Post-natal echocardiography confirmed the absence of structural heart disease and detected biventricular hypertrophy and LV dilation. LV end-diastolic diameter measured 24 mm (+ 3 z-score) (Fig. 1). The interventricular septum had a peculiar aspect appearing thin, almost membranous and akinetic in the proximal two thirds. Moreover, there was a severe LV dysfunction, as only the apical regions of the cardiac walls were contractile, with a biplane (Simpson) ejection fraction (LVEF) of 26% (Fig. 2). Both atrioventricular valves showed thickened leaflets with preserved mobility and severe regurgitation. No pericardial or pleural effusion were present.

The neonate was started on furosemide and captopril and, because of recurrent episodes of poorly tolerated rapid atrial ectopic tachycardia, on amiodarone. He was initially supported by nasal CPAP and then, upon discharge, he weaned to heated high flow nasal cannula but not to spontaneous ventilation. Extended metabolic screening was performed and was negative.

During the four months of hospitalization, the infant remained in good clinical conditions, echocardiography showed stable cardiac function (LVEF 25–30%) and dimensions. Medical therapy was continued and increased up to the dosage of captopril 0,5 mg/kg every 6 h and furosemide 1 mg/kg every 8 h. Full enteral feeding was reached at three weeks of life, tube feeding was occasionally maintained to prevent the baby’s fatigue. Patient’s growth was regular and satisfactory.

To exclude skeletal muscular involvement, electromyography was undertaken and resulted normal. Diaphragm and intercostal muscles were studied with noninvasive electromyography at different level of noninvasive respiratory support (10 L, 5 L high flow nasal cannula) and in spontaneous breathing and was also normal.

After discharge, at ten months of life, echocardiogram showed improved ventricular function with LVEF 35-40%. He is currently twenty-four months old, he is in good clinical conditions, weaned from respiratory high flow nasal cannula support. Ventricular function at echocardiogram is stable, with good adherence and tolerability to medical therapy. Psychomotor development has been evaluated as adequate.

A trio-based whole exome sequencing (WES) was performed in the patient and both parents [11]. Briefly, the exonic and flanking splice junctions’ regions of the genome were captured using the Clinical Research Exome v.2 kit (Agilent Technologies, Santa Clara, CA). Sequencing was performed on a NextSeq500 Illumina system with 150 bp paired-end reads. Reads were aligned to human genome build GRCh37/UCSC hg19 and analyzed for sequence variants using a custom-developed analysis tool. On average, coverage on target was ≥ 10X for 98% with a mean coverage of 106X. Trio-based WES identified in the proband the homozygous variant c.1156dup (p.Met386fs) in the NEXN gene (NM_144573.4); both parents were confirmed to be carriers of the same variant at the heterozygous state. To our knowledge, this NEXN variant c.1156dup has never been previously reported and is absent from population database (GnomAD). According to the American College of Medical Genetics and Genomics (ACMG) criteria [12], the variant can be interpreted as likely pathogenic (class 4).

Since the few NEXN-heterozygous CMP cases reported in adults developing DCM, HCM or overlapping forms, complete cardiac evaluation was offered to all first-degree relatives. Parents, both heterozygous for the c.1156dup variant, denied personal history of cardiac disease and symptoms of coronary artery disease (CAD) or HF; paternal grandmother died suddenly at the age of 67 for unknown reasons, and a cousin of the mother suffered from Sudden Cardiac Death (SCD) at the age of 47.

The mother, a 38-year-old woman, shows early signs of CMP, consistent with the diagnosis of Hypokinetic non-dilated Cardiomyopathy: left bundle branch block (LBBB) with consequent ventricular dyssynchrony and mildly reduced LVEF (51%), at TTE (TransThoracic Echocardiography) and CMR (Cardiac Magnetic Resonance).

The only cardiac remarkable finding for the father, a man aged 45, is mild LV hypertrophy at TTE. CMR showed normal function (LVEF 57%) and morphology of the left ventricle (EDV 82 ml/mq), with no evidence of edema or fibrosis. Since left ventricular hypertrophy is common in arterial hypertension, we can conclude that the patient’s father does not reach the criteria for possible cardiomyopathy at this time of follow-up. All three asymptomatic siblings aged 13, 15 and 17 years had normal ECG and echocardiograms. Therefore, also considering the absence of affected relatives before adulthood, they have not been tested yet for the familial variant.

Case 2

Patient 2 (P2) was prenatally diagnosed with DCM at the third trimester of pregnancy. Family history was negative for cardiovascular diseases or recurrent miscarriages. His Italian healthy parents had a remote degree of consanguinity (they both come from a small town in Southern Italy). Prenatal karyotype performed on amniotic fluid revealed a paternally inherited supernumerary marker chromosome, that was also present in the healthy sister.

The patient was born full term by cesarean section. Birth weight was 3600 g (68th percentile), length 51 cm (63th percentile) and OFC 35 cm (62th percentile). Medical treatment for HF was started since birth including diuretics and ACE inhibitors. The patient was referred to our center at the age of 4 years old. Ross functional class was II-III. Echocardiography showed moderate to severe LV dilatation and dysfunction (LVEF 31%), apical LV hypertrabeculation, moderate left atrial dilatation (Vol. 35 ml; 54 ml/m2) and moderate mitral valve regurgitation with tethering of posterior leaflets and focal thickening of the distal part of both mitral leaflets. Medical treatment was modified by adding carvedilol, spironolactone and acetyl salicylic acid. Due to persistent severe LV dysfunction, carvedilol was progressively increased since the age of 5 years old. At the age of 6 years, LVEF increased to 38%. The patient has always shown good adherence and tolerance to therapy. At 8 years old, CMR showed moderate LV dilatation and dysfunction, EDV (end-diastolic volume) 104 ml (indexed 117 ml/m²), ESV (end-systolic volume) 63 ml, systolic ejection 40 ml, FE 39%, mild to moderate mitral insufficiency, normal right ventricular function and dimension. At the age of 10 years, LVEF was 35%, medical therapy was supplemented with ivabradine that was well tolerated. In the following years, a progressive increase in LVEF, which reached 40–45%, was observed. Holter ECG monitoring was always normal. He was never admitted for heart failure. He is currently 15 years-old and has good and stable overall conditions. In addition, the child showed moderate developmental delay and behavioral disturbances.

Next generation sequencing (NGS) analysis was performed at the age of 5 years, on genomic DNA trios by using the Twist Custom Panel (clinical exome Twist Bioscience) on NovaSeq6000 platform (Illumina, San Diego, CA, USA). The reads were aligned to human genome build GRCh37/UCSC hg19. The Dragen Enrichment application of BaseSpace (Illumina) and Geneyx Analysis (knowledge-driven NGS Analysis tool powered by the GeneCards Suite) were used for such mutation for the variant calling and annotation. The coverage on target region was ≥ 10X for 99.4% with a mean coverage of 217.84X. Trio analysis identified the homozygous variant c.1579_1584del p. (Glu527_Glu528del) in NEXN; both parents were heterozygous. The variant was evaluated by VarSome (Kopanos et al., Bioinformatics 2018) and classified according to the American College of Medical Genetics and Genomics criteria [14] as of uncertain significance (class3). The Chromosomal Microarray Analysis was performed using the Infinium CytoSNP-850 K BeadChip (SNP-array, Illumina, San Diego, CA, USA), and identified a heterozygous maternal duplication arr[hg19] 12q21.33 (89,683,180 − 89,935,072) x3 of about 251 kb, including (Online Mendelian Inheritance in Man) the disease causing genes DUSP6 (hypogonadotropic hypogonadism with or without anosmia) and POC1B (Cone-rod dystrophy), and classified as of uncertain significance.

As for P1, following the diagnosis, parents underwent cardiac screening and follow-up (every 2–3 years) with normal ECG and echocardiography.

Discussion and conclusions

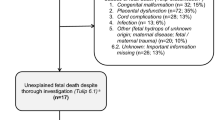

NEXN is a gene located on human chromosome 1p31.1, encoding for nexilin, a F-acting binding protein abundantly expressed in heart and skeletal muscle, and at lower levels in placenta, lung, liver and pancreas. Hassel et all. described 9 heterozygous forms in adults with DCM and an average onset age of 50 years [13]. In pediatric population a few cases of heterozygous [9, 14, 15] and even rarer cases of biallelic [8,9,10, 16] NEXN variants are reported in literature, and summarized in Table 1. The latter are all associated with very poor prognosis, more often fetal or neonatal death. Rinaldi et al. described two related fetuses with HF, reduced contractility, endocardial fibroelastosis, cardiomegaly and hydrops fetalis, as occurred in P1 here described [16]. Another case described by Bruyndonckx et al. presented with fetal hydrops and died 2 weeks postnatally [9]. Recently Johansson et al. confirm the severity of biallelic loss of function variants in NEXN gene, describing a lethal fetal form of DCM, that segregated with a recessive inheritance pattern in a large pedigree of four generation [10].

According to literature, all the heterozygous carriers in the family presented with a DCM of incomplete penetrance and different age-dependent expression. Our patients carry a NEXN homozygous variant never described to date. Based on experimental data from NEXN-related CMP physiology, both heterozygous and biallelic pathogenic variants lead to nexilin loss-of-function (LoF). While heterozygous variants, mostly non-frameshift deletion or missense, may exert LoF through different mechanisms according to the involved aminoacid residue, all biallelic variants reported so far are frameshift or nonsense, likely resulting in depletion of nexilin transcripts by means of nonsense-mediated decay. Consistently, homozygous nexilin knock-out mice show early-onset progressive DCM [17, 18]. NEXN-related CMP with fetal or neonatal onset are highly suggestive for a biallelic form and associated with a poor survival from previous reports. Nevertheless, our patients showed a reduced but stable systolic ventricular function with modest pharmacological treatment, representing the first pediatric individuals with homozygous NEXN variant and prolonged survival. Predominant echocardiographic feature in both patients was ventricular dilation, even if mild hypertrophy was also present in P1 and an apical LV hypertrabeculation was observed in P2. It is described that certain additional features may be present in the genetic forms of DCM, including increased LV wall thickness, prominent LV trabeculations and right ventricular or atrial chamber enlargement or dysfunction. These features are important because some DCM genes, such as NEXN, have been reported to cause other cardiac phenotypes, which can occasionally overlap in individuals and within families [19]. Furthermore, in P1 early onset arrhythmia was not associated with the presence of other gene alleles that could be responsible for an altered conduction system.

Considering that nexilin is also expressed in skeletal muscle, albeit to a lesser extent, in P1 we studied our patient to rule out skeletal muscle involvement. Electromyography was normal both for upper and lower limb and for respiratory muscle, although a later involvement of skeletal muscles cannot be excluded.

Our cases also emphasize the importance of family history to guide diagnosis. Consanguineity, recurrence of abortions and fetal deaths are important signs of an inheritable heart disease. Likewise, once diagnosis is made, a cardiovascular screening of asymptomatic first-degree family members is mandatory to allow early detection of CMP and improve outcome [20]. As already pointed out by Pinto YM et all. and as observed in the mother of P1, relatives may have more subtle features on ECG or echocardiography that, while not indicating a diagnosis of DCM, may still be relevant. These features include LBBB, LV enlargement, other chamber enlargement, isolated mildly reduced systolic function (LVEF 50–55%), reduced global longitudinal strain, segmental wall motion abnormalities or hyper-trabeculation [21].

Cardiomyopathies (CMPs) are inheritable heart disease characterized by genetic heterogeneity and variable penetrance and expressivity [22]. Multiple genes have been associated with CMPs, and most of these have also been shown to have extensive variation in the normal population. Interpretation of single pathogenic variants from the many thousands of rare polymorphisms present in every individual is challenging. NGS may be useful for clinicians to address diagnosis definition, provide more precise prognostic evaluations and model individualized follow-ups. The availability of genomic data may also suggest genotype-phenotype correlations [23], however, the contextual presence and potential role of other possible genetic or epigenetic factors should be considered for explaining the phenotypic variability and/or the variable clinical evolution of such patients [24].

Our cases show novel homozygous NEXN variants associated with onset in fetal life, clinical features of dilated and hypertrophic cardiomyopathy and heart rhythm disturbance with a prolonged survival. Additional individuals with NEXN-related DCM are needed to better investigate the pathological mechanisms involved for this gene.

Data availability

The datasets used and analysed during the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

Abbreviations

- DCM:

-

Dilated Cardiomyopathy

- HCM:

-

Hypertrophic Cardiomyopathy

- WES:

-

Whole Exome Sequencing

- NGS:

-

Next Generation Sequencing

- CMPs:

-

Cardiomyopathies

- HF:

-

Heart Failure

- LV:

-

Left Ventricle

- LVEF:

-

Left Ventricle Ejection Fraction

- CAD:

-

Coronary artery disease

- (LBBB):

-

Left bundle branch block

- TTE:

-

TransThoracic Echocardiography

- SCD:

-

Sudden Cardiac

- CMR:

-

Cardiac Magnetic Resonance

- LGE:

-

Late Gadolinium-Enhancement

- EDV:

-

End-diastolic volume

- ESV:

-

End-systolic volume

- OFC:

-

Occipital frontal circumference

References

Seferović PM, Polovina M, Bauersachs J, Arad M, et al. Heart failure in cardiomyopathies: a position paper from the Heart Failure Association of the European Society of Cardiology. Eur J Heart Fail. 2019;21:553–76.

Lipshultz SE, Law YM, Asante-Korang A, Austin ED, Dipchand AI, Everitt MD, Hsu DT, Lin KY, Price JF, Wilkinson JD, Colan SD. Cardiomyopathy in children: classification and diagnosis: a Scientific Statement from the American Heart Association. Circulation. 2019;140(1):e9–68.

Lodato V, Parlapiano G, Calì F, Silvetti MS, Adorisio R, Armando M, El Hachem M, Romanzo A, Dionisi-Vici C, Digilio MC, Novelli A, Drago F, Raponi M, Baban A. Cardiomyopathies in children and systemic disorders when is it useful to look beyond the heart? J Cardiovasc Dev Dis. 2022;9(2):47.

Haas J, Frese KS, Peil B, Kloos W, et al. Atlas of the clinical genetics of human dilated cardiomyopathy. Eur Heart J. 2015;36(28):1123–a35.

Hassel D, Dahme T, Erdmann J, Meder B, Huge A, Stoll M, Just S, Hess A, Ehlermann P, Weichenhan D, Grimmler M, Liptau H, Hetzer R, Regitz-Zagrosek V, Fisher C, Nürnberg P, Schunkert H, Katus HA, Rottbauer W. Nexilin mutations destabilize cardiac Z-disks and lead to dilated cardiomyopathy. Nat Med. 2009;15(11):1281–8.

Spinozzi S, Liu C, Chen Z, Feng W, Zhang L, Ouyang K, Evans SM, Chen J. Nexilin is necessary for maintaining the transverse-axial tubular system in adult. Circ Heart Fail. 2020;13(7):e006935.

Wang H, Li Z, Wang J, Sun K, Cui Q, Song L, Zou Y, Wang X, Liu X, Hui R, Fan Y. Mutations in NEXN, a Z-Disc gene, are Associated with hypertrophic cardiomyopathy. Am J Hum Genet. 2010;87(5):687–93.

Al-Hassnan ZN, Almesned A, Tulbah S, Al-Manea W, Al-Fayyadh M. Identification of a novel homozygous nexn gene mutation in recessively inherited dilated cardiomyopathy. J Saudi Heart Assoc. 2013;25:171–2.

Bruyndonckx L, Vogelzang JL, Bugiani M, Straver B, Kuipers IM, Onland W, Nannenberg EA, Clur SA, Van Der Crabben SN. Childhood onset nexilin dilated cardiomyopathy: a heterozygous and a homozygous case. Am J Med Genet. 2021;185A:2464–70.

Johansson J, Frykholm C, Ericson K, Kazamia K, Lindberg A, Mulaiese N, Falk G, Gustafsson PE, Lideus S, Gudmundsson S, Ameur A, Bondeson ML, Wilbe M. Loss of Nexilin function leads to a recessive lethal fetal cardiomyopathy characterized by cardiomegaly and endocardial fibroelastosis. Am J Med Genet A. 2022;188(6):1676–87.

Pezzani L, Marchetti D, Cereda A, Caffi LG, Manara, Mamoli D, Pezzoli L, Lincesso AR, Perego L, Pellicioli I, Bonanomi E, Salvoni L, Iascone M. Atypical presentation of pediatric BRAF RASopathy with acute encephalopathy. Am J Med Genet A. 2018;176:2867–71.

Hershberger RE, Givertz MM, Ho CY, Judge DP, Kantor PF, McBride KL, Morales A, Taylor MRG, Vatta M, Ware S, on behalf of the ACMG Professional Practice and Guidelines Committee. Genetic evaluation of cardiomyopathy: a clinical practice resource of the American College of Medical Genetics and Genomics (ACMG). Genet Med. 2018;20(9):899–909.

Hassel D, Dahme T, Erdmann J, Meder B, Huge A, Stoll M, Just S, Hess A, Ehlermann P, Weichenhan D, Grimmler M, Liptau H, Hetzer R, Regitz-Zagrosek V, Fischer C, Nürnberg P, Schunkert H, Katus HA, Rottbauer W. Nexilin mutations destabilize cardiac Z-disks and lead to dilated cardiomyopathy. Nat Med. 2009;15:1281–8.

Kean AC, Helm BM, Vatta M, Ayers MD, Parent JJ, Darragh RK. Clinical characterisation of a novel Scn5A variant associated with progressive malignant arrhythmia and dilated cardiomyopathy. Cardiol Young. 2019;29(10):1257–63.

Klauke B, Gaertner-Rommel A, Schulz U, Kassner A, Zu Knyphausen E, Laser T, Kececioglu D, Paluszkiewicz L, Blanz U, Sandica E, Van Den Bogaerdt AJ, Van Tintelen JP, Gummert J, Milting H. High proportion of genetic cases in patients with advanced cardiomyopathy including a novel homozygous plakophilin 2-gene mutation. PLoS ONE. 2017;12(12):e0189489.

Rinaldi B, Race V, Corveleyn A, Van Hoof E, Bauters M, Van Den Bogaert K, Denayer E, De Ravel T, Legius E, Baldewijns M, Aertsen M, Lewi L, De Catte L, Breckpot J, Devriendt K. Next-generation sequencing in prenatal setting: some examples of unexpected variant association. Eur J Med Genet. 2020;63(5):103875.

Aherrahrou Z, Schlossarek S, Stoelting S, Klinger M, Geertz B, Weinberger F, Kessler T, Aherrahrou R, Moreth K, Bekeredjian R, Hrabě de Angelis M, Just S, Rottbauer W, Eschenhagen T, Schunkert H, Carrier L, Erdmann J. Knock-out of nexilin in mice leads to dilated cardiomyopathy and endomyocardial firoelastosis. Basic Res Cardiol. 2016;111(1):6.

Liu C, Spinozzi S, Chen JY, Fang X, Feng W, Perkins G, Cattaneo P, Guimarães-Camboa N, Dalton ND, Peterson KL, Wu T, Ouyang K, Fu XD, Evans M, Chen S. Nexilin is a new component of junctional membrane complexes required for cardiac T-Tubule formation. Circulation. 2019;140(1):55–66.

Stacey P, Johnson R, Birch S, Zentner D, Hershberger RE, Fatkin D. Familial dilated cardiomyopathy. Heart Lung Circ. 2020;29(4):566–74.

Serra G, Antona V, D’Alessandro MM, Maggio MC, Verde V, Corsello G. Novel SCNN1A gene splicing-site mutation causing autosomal recessive pseudohypoaldosteronism type 1 (PHA1) in two Italian patients belonging to the same small town. Ital J Pediatr. 2021;47:138.

Pinto YM, Elliott PM, Arbustini E, Adler Y, Anastasakis A, Bohm M, Duboc D, Gimeno J, de Groote P, Imazio M, Heymans S, Klingel K, Komajda M, Limongelli G, Linhart A, Mogensen J, Moon J, Pieper PG, Seferovic PM, Schueler S, Zamorano JL, Caforio ALP, Charron P. Proposal for a revised definition of dilated cardiomyopathy, hypokinetic non-dilated cardiomyopathy, and its implications for clinical practice: a position statement of the ESC working group on myocardial and pericardial diseases. Eur Heart J. 2016;37:1850–8.

Hershberger RE, Jordan E, Adam MP, Mirzaa GM, Pagon RA, Wallace SE, Bean LJH, Gripp KW, Amemiya A. Dilated Cardiomyopathy Overv GeneReviews. 2007, PMID: 20301486, Bookshelf ID: NBK1309.

Piro E, Serra G, Antona V, Giuffrè M, Giorgio E, Sirchia F, Schierz IAM, Brusco A, Corsello G. Novel LRPPRC compound heterozygous mutation in a child with early-onset Leigh syndrome french-canadian type: case report of an Italian patient. Ital J Pediatr. 2020;46:140.

Serra G, Antona V, Schierz M, Vecchio D, Piro E, Corsello G. Esophageal atresia and Beckwith-Wiedemann syndrome in one of the naturally conceived discordant newborn twins: first report. Clin Case Rep. 2018;6(2):399–401.

Acknowledgements

We thank the patients and their parents for their cooperation and the consent to the publication of this study.

Funding

This study was partially funded by Italian Ministry of Health and has been generated within the European Reference Network on Rare Congenital Malformations and Rare Intellectual Disability (ERN-ITHACA) (EU Framework Partnership Agreement ID: 3HP-HP-FPA ERN-01-2016/739516).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Conceptualization I.P., A.R., A.M.C., M.F.B.; methodology M.F.B, B.R.; formal analysis I.P., A.M.C., B.R.; investigation N.P.,A.M.C, I.P.,A.R.,G.F.,M.F.B, M.I.,A.C.; data curation I.P.,M.F.B.,B.R.,A.R.,A.B.; writing—original draft preparation I.P, A.R.,B.R.M.M.; writing—review and editing visualization G.F.,A.M.C.,S.C., F.M.,A.B.,A.N.,G.P, A.C.; supervision F.M., S.C.;M.F.B. All authors have read, critically revised and approved the final manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate

The study was conducted according to the guidelines of the Declaration of Helsinki. Ethical review and approval were waived for this study, due to its nature (patient observational case report). Written informed consent was obtained from both parents at admission of their newborn.

Consent for publication

Written informed consent was obtained from the patient for publication of this case report and accompanying images.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/. The Creative Commons Public Domain Dedication waiver (http://creativecommons.org/publicdomain/zero/1.0/) applies to the data made available in this article, unless otherwise stated in a credit line to the data.

About this article

Cite this article

Picciolli, I., Ratti, A., Rinaldi, B. et al. Biallelic NEXN variants and fetal onset dilated cardiomyopathy: two independent case reports and revision of literature. Ital J Pediatr 50, 156 (2024). https://doi.org/10.1186/s13052-024-01678-x

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/s13052-024-01678-x