Abstract

Background

To reduce psychopathologies in children, various treatment approaches focus on the parent-child relationship. Disruptions in the parent-child relationship are outlined in the most recently revised versions of the Diagnostic Classification of Mental Health and Developmental Disorders of Infancy and Early Childhood (DC:0-3R/DC:0–5). The measures used to assess the parent-child relationship include the Parent-Infant Relationship Global Assessment Scale (PIRGAS) and the Relationship Problems Checklist (RPCL), which cover, e.g., essential concepts like over- or underinvolvement of the caregiver. However, not much is known about the cross-sectional and predictive value of PIRGAS and RPCL scores at admission to discharge, namely whether changes in these scores are correlated with child and maternal psychopathologies and changes through treatment.

Methods

Based on clinical records of 174 preschool-aged children of the Family Day Hospital, we report related basic descriptive data and changes from admission to discharge for the parent-child relationship, child behaviour, and maternal psychopathology. We used a Pearson correlation or a point-biserial correlation to describe the associations and performed a paired t-test to examine differences before and after measurement.

Results

Our results show overall improvements in our parent-child relationship measures and in child and maternal psychopathology. However, we observed little or no correlation between the parent-child relationship measures and child or maternal psychopathology.

Conclusions

We highlight potential drawbacks and limitations of the two relationship measures used that may explain the results of this study on the associations between the variables assessed. The discussion emphasizes the assessment of DC:0-3R/DC:0–5, which are popular in clinical practice for economic reasons.

Similar content being viewed by others

Background

Parent-child relationship in the clinical context

In 1994, the Diagnostic Classification of Mental Health and Developmental Disorders of Infancy and Early Childhood (DC:0–3) [1] was introduced to provide an alternative and probably more adequate classification of mental diseases for children between zero and three years of age [2]. This manual was later revised (DC:0-3R) [3] and then extended to preschool age with the DC:0–5 [4, 5]. In the DC:0-3R manual, a diagnostic framework is given to assess the disorder in a parent-child relationship (PCR) (DC 0–3: Axis II), and two measures are introduced: The Parent-Infant Relationship Global Assessment Scale (PIRGAS) and the Relationship Problems Checklist (RPCL) [1, 3]. The PIRGAS is a global one-item measure with a scale from 0 to 100, where scores between 91 and 100 label a relationship as well adapted, 81–90 as adapted, 71–80 as perturbed, 61–70 as significantly perturbed, 51–60 as distressed, 41–50 as disturbed, 31–40 as disordered, 21–30 as severely disordered, 11–20 as grossly impaired, and 1–10 as documented maltreatment [3]. Additionally, according to the manual, each dyad’s relationship is labelled as a disturbed relationship if the PIRGAS ≤ 40 [3]. Please note that the wording and number expression is given in the manual and does not represent our interpretation.

The RPCL classifies relevant parental behaviour for relationship problems using seven global one-item measures, labelling parenting behaviour as overinvolved, underinvolved, anxious/tense, angry/hostile, verbally abusive, physically abusive, or sexually abusive [3].

The PIRGAS and RPCL are potential candidates for assessing important theoretical and practical information to explain and treat child psychopathology [6]—even though they are more subjective and therefore susceptible to the biases inherent to all clinical assessments [7]—because they can be applied easily and quickly; this is particularly important in times of increasing economic pressure. This makes global assessment approaches more attractive than multiple-item questionnaires or observational instruments that require training. Also, from a validity perspective, a global measure may document clinical impressions better by taking the unique circumstances of a parent-child relationship into account.

However, a disadvantage of these measures is that the assessment approach in PIRGAS and RPCL is not standardized in terms of recommendations on training or regarding how long or in what setting a parent-child dyad should be observed to obtain reliable clinical information [8, 9]. While the DC:0–3/0-3R does provide vague diagnostic guidelines and names aspects that should be included in a full diagnostic evaluation [1, 3], the manual does not provide any references to a clear theoretical background or related empirical studies. A potential further limitation is that the RPCL provides only a dichotomous classification instead of a graded dimensional score. Additionally, the RPCL domains represent less a direct measure of relationship quality and instead focus on parental behaviour as cause or reaction within a reciprocal interaction schema which is also bidirectionally affected by parental and child distress [10,11,12]. Thus, our paper does not intend to add or clarify the scientific basis for these measures. Instead, given the widespread use and attractiveness of these measures, we want to know whether these global measures are useful in the context of daily routine diagnostics. In our study, useful means that the measures show covariation and concordant changes to child and maternal psychopathology. In the following section, we describe the broad usage of both measures in Table 1. Note that because the newer version DC:0–5 published in 2016 lacks instruments for assessing the parent-child relationship, we assume that the PIRGAS and RPCL may still be applied in clinical practice or still used in research studies, as in Brann et al., 2021 [13].

Pirgas and the Rpcl

PIRGAS and the RPCL show a wide range between study samples (Table 1). Skovgaard et al. indicated that the methodological diversity between the studies may explain the large variation in frequencies [14], but it may also be due to the largely unstandardized assessment conditions regarding observed interaction settings, raters, and duration of the observation as well as the absence of clear criteria for assigning the diagnosis on Axis II [9].

An association between PIRGAS and RPCL measures and specific diagnoses according to Axis I of the DC:0–3/0-3R could have not be found [18], but an association does exist on a more global level of having or not having any mental health diagnosis according to ICD 10 [20, 21]. The PIRGAS shows a spearman correlation of r = −.23 with aggressiveness [22], a correlation with increased internalizing behaviour [23], and moderate [24] to strong effects [13] in treatment evaluation. Therefore, the clinical value of the RPCL categories may be in their ability to point to parental behaviours that may explain disruptions in the parent-child relationship; these behaviours may lead to specific treatment goals and therapeutic foci. In the preprint of this article, we described several correlations regarding parenting behaviours that can lead to increased internalizing or externalizing problems [25].

Research question

Before describing our research question, it is important to describe the general treatment effects we observed in terms of the impact on child psychopathology [26] and in relation to parental outcomes [27]. Specifically, we observed an improvement in child psychopathology (d = -0.50) and parental psychopathology (d = 1.64) [26, 27]. Given these effects, we would expect concordant changes in parenting behaviour described by the RPCL and PIRGAS.

Methods

The Family Day Hospital

The Family Day Hospital is a part of the Clinic for Child and Adolescent Psychiatry, Psychosomatics, and Psychotherapy of the University Hospital in Münster, Germany, and provides an eclectic interactional family-centred approach for infants, toddlers, and preschoolers from birth to approximately six years of age and their caregivers as part of a multimodal approach [28, 29]. The treatments include parent groups, children’s groups, video-based parent-child interaction therapy, and individual sessions with the parents and family [28].

Procedure

Our data are based on a retrospective clinical record data collection for 174 children and their caregivers treated at the Family Day Hospital between 2002 and 2012. This study was approved by the local ethics committee of the University Hospital of Münster.

Sample

The characteristics of the sample are presented in Table 2. Most dyads in our sample consisted of mother and child (171 out of 174).

Measures

PIRGAS and the RPCL were already introduced in the introduction. It should be noted that the frequency of all ‘abusive’ RPCL categories was very low or zero, so these were not included in the subsequent analysis. Furthermore, therapists and parents filled out the TRF/CBCL 1.5-5 as described in Müller et al. 2011 and 2013 [30, 31]. Their composite score was used to facilitate the analysis. Moreover, the Symptom Checklist 90-Revised (SCL-90-R) [32] was completed by the same parent.

Statistical analysis

We performed the statistical analysis using the Statistical Package for Social Science (IMB SPSS 29). The alpha level was set at p <.05, and one-tailed testing was applied whenever reasonable.

Results

Parent-child relationship and psychopathology at admission and discharge

Shown in Table 3, the PIRGAS classified 58.38% of the clinical sample as having a disturbed relationship, while 88.24% was classified as having at least one questionable parenting behaviour. The frequency profile across the RPCL subgroup classifications was relatively stable from admission to discharge, but by the end of therapy these frequencies were reduced by 10–20% depending on the RPCL category. The greatest reduction was observed for the category angry/hostile.

Changes between parent-child relationship and clinical symptom scales

In Table 4 we present the bivariate associations between PIRGAS and RPCL measures with the clinical symptom scale of child externalizing and internalizing behaviour and maternal psychopathology at admission, discharge, and their concordant changes.

Discussion

Parent-child relationship diagnostic at admission and changes during treatment

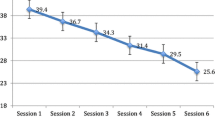

The main question of this study relates to whether global assessments of parent-child relationship (PIRGAS) and parental behaviour (RPCL categories) used in routine clinical practice predict a concomitant reduction in child or parental psychopathology when improved. Underpinning this analysis are the previously reported strong improvements related to children’s internalizing and externalizing symptoms as well as parental psychopathology in the course of treatment at the Family Day Hospital [26, 27]. Additionally, in relation to the RPCL, we observed the occurrence of questionable parental behaviour at admission and a reduction at discharge with respect to overinvolved, underinvolved, and especially angry/hostile behaviour; the reduction in anxious/tense behaviour was not significant. The PIRGAS cutoff classification indicated a disturbed relationship for approximately 40% of the parent-child dyads at admission, while at discharge the metric PIRGAS score showed a considerable improvement of d = − 1.1. Related to our main hypothesis, we did not observe concordant improvement between the improvements related to the RPCL categories and children’s and parents’ psychopathology and only a weak association between improvement in PIRGAS and children’s internalizing and externalizing behaviour. This pattern was already apparent for the cross-sectional scores at admission and at discharge.

Our findings can be explained by the assumption that the RPCL categories in particular are not sufficiently standardized, which is likely a consequence of single-item global ratings with a dichotomous answer format. This may also explain the variation in prevalence in other studies (Table 1). Aside from the methodological limitations of global ratings, we consider conceptual limitations to be even more important because the RPCL was designed to assess questionable or potential negative parental behaviour but not diverse variants of positive parenting behaviour like scaffolding, support, or accepting behaviour, whose promotion is probably more effective than eliminating dysfunctional behaviours [33]. The DC:0–5 no longer includes these assessment instruments, but because clinicians still consider the content and observational approach as highly relevant to their work [34] and the DC:0–5 lacks comparable alternative measurement instruments, they are likely to still use these measures in practice for diagnostics and to validate other measures, as in Brann et al., 2021 [13].

Limitations and strengths

Our clinical sample covered a considerable variation and improvement in child and maternal psychopathology as well as in the parent-child relationship measures within a longitudinal design. Moreover, the sample size allowed for sufficient statistical power, and the data were collected with a focus on proximity to real practice during the clinic staff’s daily routines. However, we did not include data belonging to father-child dyads or relationships to other family members who may be important for the child in question. Our results should be interpreted with caution and should not be overrated in terms of their importance for guiding practitioners’ case formulation and treatment planning.

Conclusions

Global measures such as PIRGAS and RPCL are popular in times of growing economic pressure, not simply due to their ease of use. However, we see many disadvantages concerning the reliability and design of the RPCL, particularly with respect to the lack of assessment of positive parenting behaviour. The lack of association between the RPCL categories and the PIRGAS also indicates that the PIRGAS may not cover all facets of a disturbed relationship. These limitations may also explain why changes in children’s internalizing or externalizing behaviour were not associated with improvements in PIRGAS or reductions in negative parental behaviour (RPCL). We conclude that further test development to assess clinically relevant aspects and constructs and their validation is still needed.

Data availability

The datasets used and/or analysed during the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

Abbreviations

- DC:0-3R:

-

Diagnostic Classification of Mental Health and Developmental Disorders of Infancy and Early Childhood. Revised edition (DC:0-3R)

- DC:0-5:

-

Diagnostic Classification of Mental Health and Developmental Disorders of Infancy and Childhood: Revised edition (DC:0-5)

- PCR:

-

Parent-child relationship

- PIRGAS:

-

Parent-Infant Relationship Global Assessment Scale

- RPCL:

-

Relationship Problems Checklist

- TRF:

-

Teacher’s Report Form

- SCL-90-R:

-

Symptom Checklist 90-Revised

- GSI:

-

Global Severity Index

References

Zero. to Three. DC:0–3: Diagnostic classification of mental health and developmental disorders of infancy and early childhood. Washington DC, US: ZERO TO THREE: National Center for Infants, Toddlers, & Families; 1994.

Postert C, Averbeck-Holocher M, Beyer T, Müller J, Furniss T. Five systems of psychiatric classification for preschool children: do differences in validity, usefulness and reliability make for competitive or complimentary constellations? Child Psychiatry Hum Dev. 2009;40(1):25–41.

Zero to Three. DC:0-3R: diagnostic classification of mental health and developmental disorders of infancy and early childhood: revised edition (DC:0-3R). Washington DC, US: ZERO TO THREE: National Center for Infants, Toddlers, & Families; 2005.

Zero to, Three. DC:0–5: Diagnostic classification of mental health and developmental disorders of infancy and childhood: Revised edition (DC:0–5). Washington DC, US: ZERO TO THREE National Center for Infants, Toddlers and Families; 2016.

Zero to, Three. DC:0–5: Diagnostic classification of mental health and developmental disorders of infancy and early childhood. Revised version (DC:0–5)(Version 2.0). Washington DC, US: ZERO TO THREE: National Center for Infants, Toddlers, & Families; 2021.

Wiefel A, Titze K, Kuntze L, Winter M, Seither C, Witte B, et al. Diagnostik Und Klassifikation Von Verhaltensauffälligkeiten Bei Säuglingen Und Kleinkindern Von 0–5 Jahren. Prax Kinderpsychol Kinderpsychiat. 2007;56:59–81.

Wright T, Stevens S, Wouldes TA. Mothers and their infants co-admitted to a newly developed mother–baby unit: characteristics and outcomes. Infant Ment Health J. 2018;39(6):707–17.

Guédeney N, Guédeney A, Rabouam C, Mintz AS, Danon G, Moralès Huet M, et al. The zero-to-three diagnostic classification: a contribution to the validation of this classification from a sample of 85 under-threes. Infant Ment Health J. 2003;24(4):313–36.

Müller JM, Achtergarde S, Frantzmann H, Steinberg K, Skorozhenina O, Beyer T et al. Inter-rater reliability and aspects of validity of the parent-infant relationship global assessment scale (PIR-GAS). Child Adolesc Psychiatry Ment Health. 2013;7(17).

Roskam I. Externalizing behavior from early childhood to adolescence: prediction from inhibition, language, parenting, and attachment. Dev Psychopathol. 2019;31(2):587–99.

Wu CY, Lee TSH. Impact of parent–child relationship and sex on trajectories of children internalizing symptoms. J Affect Disord. 2020;260:167–73.

Mathijssen JJJP, Koot HM, Verhulst FC, De Bruyn EEJ, Oud JHL. The relationship between mutual family relations and child psychopathology. 39, J Child Psychol Psychiat. 1998.

Brann P, Culjak G, Kowalenko N, Dickson R, Coombs T, Burgess P et al. Health of the Nation Outcome scales for infants field trial: concurrent validity. BJPsych Open 2021;7(4).

Skovgaard AM. Mental health problems and psychopathology in infancy and early childhood. An epidemiological study. Dan Med Bull. 2010;57(10).

Cordeiro MJ, Caldeira Da Silva P, Goldschmidt T. Diagnostic classification: results from a clinical experience of three years with DC: 0–3. Infant Ment Health J. 2003;24(4):349–64.

Keren M, Feldman R, Tyano S. A five-year Israeli experience with the DC: 0–3 classification system. Infant Ment Health J. 2003;24(4):337–48.

Minde K, Tidmarsh L. The changing practices of an Infant Psychiatry Program: the McGill experience. Infant Ment Health J. 1997;18(2):135–44.

Maldonado-Durán M, Helmig L, Moody C, Fonagy P, Fulz J, Lartigue T, et al. The zero-to-three diagnostic classification in an infant mental health clinic: its usefulness and challenges. Infant Ment Health J. 2003;24(4):378–97.

Akca OF, Ugur C, Colak M, Kartal OO, Akozel AS, Erdogan G, et al. Underinvolved relationship disorder and related factors in a sample of young children. Early Hum Dev. 2012;88(6):327–32.

Skovgaard AM, Houmann T, Christiansen E, Landorph S, Jørgensen T, Olsen EM, et al. The prevalence of mental health problems in children 1(1/2) years of age - the Copenhagen Child Cohort 2000. J Child Psychol Psychiatry. 2007;48(1):62–70.

Skovgaard AM, Olsen EM, Christiansen E, Houmann T, Landorph SL, Jørgensen T, et al. Predictors (0–10 months) of psychopathology at age 1 1/2 years - a general population study in the Copenhagen child cohort CCC 2000*. J Child Psychol Psychiatry. 2008;49(5):553–62.

Thomas JM, Clark R. Disruptive behavior in the very young child: diagnostic classification: 0–3 guides identification of risk factors and relational interventions. Infant Ment Health J. 1998;19(2):229–44.

Aoki Y, Zeanah CH, Heller SS, Bakshi S. Parent-infant relationship global assessment scale: a study of its predictive validity. Psychiatry Clin Neurosci. 2002;56(5):493–7.

Salomonsson B, Sandell R. A randomized controlled trial of mother-infant psychoanalytic treatment: II. Predictive and moderating influences of qualitative patient factors. Infant Ment Health J. 2011;32(3):377–404.

Baans NEU, Janßen M, Müller JM. Parent-Child Relationship Measures and Pre-Post Treatment Changes for a Clinical Preschool Sample Using DC:0-3R. 2023; https://doi.org/10.21203/rs.3.rs-3480635/v1.

Müller JM, Averbeck-Holocher M, Romer G, Fürniss T, Achtergarde S, Postert C. Psychiatric treatment outcomes of preschool children in a family day hospital. Child Psychiatry Hum Dev. 2015;46(2):257–69.

Liwinski T, Romer G, Müller JM. Evaluation einer tagesklinischen mutter-kind-behandlung für belastete Mütter Psychisch Kranker Kinder. Prax Kinderpsychol Kinderpsychiat. 2015;64:254–72.

Postert C, Achtergarde S, Wessing I, Romer G, Fürniss T, Averbeck-Holocher M, et al. Multiprofessionelle Intervallbehandlung psychisch kranker Kinder Im Vorschulalter und ihrer Eltern in Einer Familientagesklinik. Prax Kinderpsychol Kinderpsychiatr. 2014;63(10):812–30.

Furniss T, Müller JM, Achtergarde S, Wessing I, Averbeck-Holocher M, Postert C. Implementing psychiatric day treatment for infants, toddlers, preschoolers and their families: a study from a clinical and organizational perspective. Int J Ment Health Syst. 2013;7(12).

Müller JM, Achtergarde S, Furniss T. The influence of maternal psychopathology on ratings of child psychiatric symptoms: an SEM analysis on cross-informant agreement. Eur Child Adolesc Psychiatry. 2011;20(5):241–52.

Müller JM, Furniss T. Correction of distortions in distressed mothers’ ratings of their preschool children’s psychopathology. Psychiatry Res. 2013;210(1):294–301.

Derogatis LR. SCL-90-R, administration, scoring & procedures manual-I for the R(evised) version. Baltimore. Maryland, US: John Hopkins University School of Medicine.; 1977.

Puckering C, Allely CS, Doolin O, Purves D, McConnachie A, Johnson PCD et al. Association between parent-infant interactions in infancy and disruptive behaviour disorders at age seven: a nested, case-control ALSPAC study. BMC Pediatr. 2014;14(223).

Müller JM, Hoffmann VA, Janssen M. Diagnostic of parent-child-interaction and their relationship: results from a multiprofessional and task specific survey. Prax Kinderpsychol Kinderpsychiatr. 2023;72(1):32–49.

Acknowledgements

Not applicable.

Funding

Open Access funding enabled and organized by Projekt DEAL.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

B.N.E.U: literature search, methodology, data collection, writing—review and editing —first draft. J.M.M: assessment design, data collection, methodology, interpretation, supervision. M.J: conception, assessment design, methodology, data analysis, writing, interpretation, supervision. All authors have approved the final version of the manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Ethics approval

The study was approved by the Ethics Committee of the Medical Association of the Physicians Chamber Westfalen-Lippe (AZ: 2013-620-f).

Informed consent

Informed consent was obtained for all participants in this study.

Consent For publication

Not applicable.

Additional information

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/. The Creative Commons Public Domain Dedication waiver (http://creativecommons.org/publicdomain/zero/1.0/) applies to the data made available in this article, unless otherwise stated in a credit line to the data.

About this article

Cite this article

Baans, N.E.U., Janßen, M. & Müller, J.M. Parent-child relationship measures and pre-post treatment changes for a clinical preschool sample using DC:0-3R. Child Adolesc Psychiatry Ment Health 18, 56 (2024). https://doi.org/10.1186/s13034-024-00746-8

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/s13034-024-00746-8