Abstract

Introduction

Child and adolescent mental health is a global priority. In sub-Saharan Africa, despite the high burden, there is a gap in health services for children and adolescents with mental health disorders. To bridge this gap, healthcare workers require a good understanding of child and adolescent mental health, the right attitude, and practices geared to improving child and adolescent mental health. This scoping review examined the knowledge, attitudes, and practices related to child and adolescent mental health among sub-Saharan African healthcare workers.

Methods

The search was restricted between January 2010, the year when the Mental Health Gap Action Programme guidelines were launched, and April 2024. The review followed the methodological framework proposed by Arksey and O’Malley for conducting scoping reviews. The databases searched included CINHAL, PubMed, Web of Science, PsycINFO, and grey literature databases. Additional articles were identified through cited references of the studies included. A data extraction template was used to retrieve relevant text. A narrative synthesis approach was adopted to explore the relationships within and between the included studies.

Results

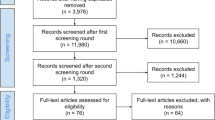

The literature search yielded 4658 studies. Among these, 817 were identified as duplicates, and 3740 were excluded after screening. Only twenty-one articles met the criteria for inclusion in the review. The findings showed that healthcare workers have insufficient knowledge of child and adolescent mental health, hold negative attitudes toward children and adolescents with mental health problems, and exhibit poor practices related to child and adolescent mental health.

Conclusion

It is crucial to build capacity and improve healthcare workers’ practices, knowledge, and attitudes toward child and adolescent mental health in sub-Saharan Africa. This could lead to better access to mental health services for children and adolescents in the region.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Globally, there is a high burden of Child and Adolescent Mental Health (CAMH) disorders [1,2,3]. The prevalence of CAMH disorders is estimated to be between 10 and 20%, with one in five children experiencing mental health problems [4, 5]. CAMH disorders are a leading cause of health-related disability in children and adolescents, and their effects can persist throughout life [6]. The Mental Health Gap Action Programme (mhGAP) Intervention Guide classifies CAMH disorders into developmental disorders such as autism, emotional disorders such as adolescent depression, and behavioral disorders such as conduct disorders [7].

In sub-Saharan Africa (SSA), one in every seven children and adolescents (14.3%) has a serious psychological problem [8]. A systematic review and meta-analysis of SSA countries, which included 46, 464 adolescents from 22 studies, reported a prevalence of mental health disorders was 23% [9]. Another systematic review of 97,616 adolescents found the following prevalence estimates: 40.8% for emotional and behavioral difficulties, 29.8% for anxiety disorders, 26.9% for depression, 21.5% for PTSD, and 20.8% for suicide ideation [10]. A significant variation from the prevalence reported in a review of 14 studies from 11 high-income countries, including 61, 545 children aged 4 to 18, that reported the prevalence of anxiety to be 5.2%, attention-deficit hyperactivity 3.7%, conduct 1.3%, and depressive disorders 1.3% [11]. The high burden of CAMH disorders is compounded by a lack of health services and in many SSA countries, the treatment gap can be as high as 75% [8, 9]. For instance, in Kenya, there are fewer than 500 specialist mental health workers serving a population of over 50 million [12].

CAMH care in SSA countries is influenced by a complex set of factors, including unique contexts and challenges. Factors such as poverty, limited access to mental healthcare, and inadequate healthcare infrastructure pose significant obstacles in mental healthcare in already overstretched health systems [13]. Due to competing health and development priorities and insufficient funds, mental healthcare in many SSA countries is severely underfunded and often under-prioritized [14]. Data collection systems often overlook mental health, contributing to policymakers’ lack of understanding of the extent of the problem [15]. In most SSA countries, the CAMH services are mostly available at tertiary health facilities [16,17,18]. Additionally, there are no clear referral pathways [19]. The integration of services in primary healthcare is also suboptimal [20]. Cultural beliefs and stigma surrounding mental illness often lead to neglect of mental health needs [21]. The mental health needs of children and adolescents with these disorders are frequently overlooked, and early identification is limited [22].

Recommendations have been made to decentralize CAMH care services to primary healthcare facilities to establish a robust health system for CAMH services and build capacity even at the lowest level of health systems [23,24,25]. However, for this process to be effective and successful, it is crucial to enhance the knowledge, attitudes, and practices (KAP) of healthcare workers (HCWs) regarding CAMH [26,27,28,29,30]. In most SSA countries, HCWs can fall into several cadres but mostly include nurses, midwives, medical doctors, clinical officers, psychologists, social workers, and community health workers [12]. Despite the many cadres, only a few HCWs within these cadres, such as psychiatrists, psychologists, and mental health nurses are adequately trained to provide mental healthcare [31]. Furthermore, an even smaller proportion of these professionals have specialized in CAMH. The few who possess such training are employed in higher-level healthcare facilities and the private sector [32]. This translates to inadequate knowledge about CAMH and subsequent poor attitude and practices among this workforce [14]. HCWs’ knowledge of CAMH can be described as understanding CAMH concepts, the different CAMH disorders, their symptoms, causes, diagnostic criteria, and available treatment options [26, 27, 30]. Attitudes refer to the beliefs, opinions, and emotional responses of HCWs toward individuals with CAMH disorders [27, 33]. Positive attitudes entail empathy, carefulness, and a non-judgmental approach that recognizes the importance of mental health in children and adolescents [29, 34]. Healthcare workers’ practices involve assessing, treating, and managing CAMH disorders [28, 35, 36]. Therefore, by enhancing the KAP of HCWs regarding CAMH, it becomes feasible to establish a robust health system for CAMH services and build capacity even at the lowest level of health systems, facilitating the decentralization of CAMH care services to primary healthcare facilities.

In 2008, the World Health Organization (WHO) released the mhGAP Intervention Guide, which was updated to version 2 in 2016 [7, 37]. Recently, in November 2023, the WHO updated the mhGAP based on research evidence [38]. These guidelines are used to assess and diagnose mental health issues, including those in children and adolescents, in non-specialist healthcare settings, such as primary healthcare facilities [7, 37, 38]. The release of the mhGAP intervention guide was a significant milestone in integrating mental health into primary healthcare systems and building HCWs’ capacity to provide mental health services, including CAMH services.

In SSA, studies on mental health, including CAMH, have received increased attention since the launch of the mhGAP guidelines. Several studies have reported on the KAP of HCWs regarding CAMH-related issues in SSA. For example, a study conducted in Nigeria found that non-specialized medical doctors had limited knowledge of autism, an important CAMH disorder [39]. Similarly, in Uganda, HCWs had difficulties in making a diagnosis, had a poor understanding of autism symptoms, and had misconceptions about how autism presents [40]. Additionally, children and adolescents with mental illness often experience stigma from HCWs [27, 41], highlighting the need for capacity building programs aimed at improving HCWs’ KAP toward CAMH [26, 40, 42]. Currently, some countries in sub-Saharan Africa, such as Nigeria, are implementing formal CAMH training programs to build human resource capacity for CAMH needs [43]. Following the launch and integration of mhGAP, it is important to summarize the state of evidence on the KAP on CAMH among HCWs from SSA given that the guidelines were launched to bridge the gap in HCWs’ KAP on mental health, including CAMH, especially in non-specialist healthcare settings. Until now, to our knowledge, no scoping or systematic reviews on this topic have been conducted on this topic. This review aims to fill this gap.

This scoping review aimed to map out research evidence on knowledge, attitudes, and practices regarding CAMH among HCWs in SSA. The findings of this review could aid in the development of policies and interventions tailored to bridge the gap on KAP about CAMH among health HCWs in this context.

Methods

The scoping review was guided by the methodological framework proposed by Arksey and O’Malley for conducting a scoping review [44]. Arksey and O’Malley’s framework comprises several steps: first, formulating the research question; second, identifying relevant studies; third, conducting the study selection and data charting; thereafter, consolidating, summarizing, and presenting the results; and finally, an optional step involving a consultation exercise [44, 45]. The final review protocol was registered prospectively with the Open Science Framework on 19th February 2023. The protocol can be accessed using this link: https://osf.io/rv92q/.

Eligibility criteria

To be included in the review, the study population needed to be HCWs, such as clinicians, nurses, doctors, community HCWs/volunteers, psychologists, or psychiatrists. The articles were included if they examined the knowledge, attitudes, or practices toward CAMH, CAMH disorders, child mental health, or adolescent mental health, as reported by the studies.

Any original empirical research, such as randomized controlled trials, quasi-experimental designs, pre-post evaluations, open trials, qualitative studies, quantitative studies, and mixed-method studies, were considered for inclusion. Articles published in any language were considered. The time for inclusion was from 1st January 2010 to 06th April 2024, which includes more than a decade of research regarding HCWs’ KAP since the introduction of the mhGAP in 2008. Reviewing literature from 2010 provides a 2-year window of opportunity for implementing the mhGAP guidelines since its launch. The KAP framework was adopted for use in this review, over others such as the Mental Health Literacy framework [46], given its holistic approach to comprehensively assess our topic, identify gaps, establish baseline assessments, and facilitate cross-cultural comparisons, including in mental health [47,48,49,50,51]. The KAP framework is widely used for demonstrating societal context in public health research [52]. The information generated through studies utilizing the KAP framework can be used to develop strategies, including mental health-related, with a focus on improving the behavioral and attitudinal changes driven by the level of knowledge, perceptions, and practices [47, 48, 50]. The articles included reported findings from SSA countries, which are listed in Appendix 1 of Additional file 1.

Information sources

An initial basic search was conducted in the PubMed database to identify relevant sources of evidence by refining key concepts such as “child and adolescent mental health”, “knowledge”, “attitudes”, “experiences”, “practices”, and “healthcare professionals.” The text words found in the titles and abstracts of pertinent articles, as well as the index terms used to describe the articles, were used to develop a comprehensive search strategy for the review. The refined search strategy concepts and their synonyms were connected using Boolean operators “OR” and “AND” and then applied to all the databases listed, including CINHAL, PubMed, Web of Science, and PsycINFO. Furthermore, gray literature databases and cited references of included studies were searched, such as Think Tank Search and Open Grey. The final search strategy used in PubMed can be found in Appendix 2 of Additional file 1. Additionally, reference tracking and hand-searching were conducted to identify any relevant articles published after the indexing process.

Selection of sources of evidence

Following the search, all identified citations were collected and uploaded into the Evidence for Policy and Practice Information (EPPI) Reviewer, a software used to conduct literature reviews [53]. Duplicates were removed, and titles and abstracts were screened against the review’s inclusion criteria. Relevant sources of evidence were retrieved in full, and their citation details were imported into EndNote X9. The full text of selected citations was thoroughly assessed against the inclusion criteria by two independent reviewers, and reasons for excluding sources of evidence that did not meet the criteria were recorded and reported. Any disagreements between the reviewers were resolved through discussions with additional reviewers in the authorship.

Data charting process

Data from the articles included in the review were extracted and charted by two independent reviewers (BM and BN) using a data extraction template designed in MS Excel. The reviewers filled in the template independently (see Additional file 1: Appendix 3). The data extracted were on the study population, concept, context, study methods, and key findings that were relevant to the review question. The data extraction tool was modified and revised as necessary while extracting data from each article included. Any disagreements between the reviewers were resolved through discussions or consultation with an additional reviewer.

Data items

We extracted information regarding various aspects of the articles, such as their country of origin, study methodology, intervention features (if present), and HCWs’ attitudes, knowledge, or practices regarding child or adolescent mental health.

Quality assessment of included papers

The review assessed the potential bias of the articles included by employing the Newcastle–Ottawa Scale [54]. This scale evaluated studies across three domains: participant selection, comparability of study groups, and ascertainment of exposure or outcome. Cohort studies were awarded a maximum of nine stars, while cross-sectional studies could receive up to ten. The final star rating was then used to categorize studies as unsatisfactory (0–4), satisfactory (5–6), good (7–8), or very good (9–10) [54]. Additional information can be found in the supplementary file.

Data analysis and presentation

Data were extracted and analyzed in MS Excel©. Thematic analysis was used to give a narrative account of the data extracted from the studies included [55]. Data were extracted around the following outcomes: knowledge of CAMH, attitudes toward children and adolescents with mental health problems, perceptions toward CAMH problems, and management practices of CAMH problems. A narrative summary accompanied by tabulated results was used to present the results related to the review objective.

Results

The search results are presented in a flow diagram following the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-analyses extension for scoping review (PRISMA-ScR) in Fig. 1 [56].

The characteristics and key findings of the 21 sources of evidence included in this scoping review are presented in Table 1. All 21 papers were published between 2011 and 2023. The majority (90.5%, n = 19) were published within the last decade (2014–2024), with 42.9%, (n = 9) published in the last 5 years (2020–2024). Three out of the six grey literature articles identified were dissertations.

Study designs

Of the 21 sources of evidence included in the scoping review, 15 were cross-sectional studies [28, 33, 35, 39,40,41, 43, 57,58,59,60,61,62,63,64], one was a longitudinal cohort study [65], one was an experimental pretest–posttest design [27], two were mixed methods papers [22, 66], and two were exploratory studies [67, 68].

CAMH disorders

The most described CAMH disorder was autism, which was reported in ten papers [33, 39, 40, 57, 58, 60, 62,63,64, 68], papers described CAMH in general [27, 28, 35, 43], one reported on child and adolescent mental illness [41], two reported on developmental disorders [22, 67], one on child mental health [59], one on adolescent depression [65], one on Tourette’s Syndrome [66], and one on psychomotor development of children [61].

Geographic distribution

There were six studies from Nigeria [27, 35, 39, 41, 43, 57], and four from Uganda [22, 28, 40, 66]. Four studies were from Ethiopia [33, 59, 68], two from Ghana [58, 67], two from South Africa [60, 63], one from Congo [61], one from Kenya [64], and one from Tanzania [65]. The geographic distribution of studies is shown in Fig. 2.

Target population

The healthcare workers represented in the reviewed studies were mostly nurses [22, 27, 28, 35, 41, 43, 57, 58, 61,62,63,64,65, 67, 68], followed by midwives [22, 28, 65, 67] and medical doctors [39, 41, 43, 64, 67]. Clinical officers were evaluated in three studies [22, 28, 64, 65]. Other health professionals included in the studies were health extension workers [33, 59] and community HCWs [35, 65]. Two of the studies focused on psychologists and social workers [41, 68]. Some papers used the general terminology ‘healthcare workers’ or ‘health professionals’ or ‘health care practitioners [40, 60, 66].

Measures of evaluation

Most of the studies (57.1%) did not use a standardized tool to evaluate the outcomes of interest [22, 33, 35, 43, 59, 62,63,64,65,66,67,68]. One-third (33.3%) of the studies used the Knowledge about Childhood Autism among HCWs (KCAHW) questionnaire [39, 40, 57, 58, 62,63,64]. The two studies that trained HCWs using mhGAP guidelines utilized the standard mhGAP knowledge test [27, 28]. One study conducted in Nigeria used a Stigmatizing Scale and a Knowledge of Child and Adolescent Mental Illness Scale [41].

Synthesis of results on knowledge, attitudes, and practices

Ten of the included studies reported on knowledge only [39, 40, 57, 58, 61,62,63,64, 67, 68]. Only two papers evaluated all three outcomes of interest related to the review, namely, knowledge, attitude, and practices related to CAMH [61, 65]. One paper reported on attitudes [33], one on both knowledge and practices [35], and two studies on knowledge and attitudes toward CAMH [28, 41]. Several studies that reported knowledge, attitudes, or practices also reported other related concepts, such as confidence, beliefs, and competence [22, 33, 35, 43, 59, 60, 69]. The sections below summarize the findings related to HCWs’ CAMH knowledge, attitudes, and practices for the studies included in this review.

Knowledge related to CAMH

Seven studies (two in Nigeria and one in Ghana, Ethiopia, Kenya, South Africa, and Uganda) that used the KCAHW questionnaire showed an evident knowledge gap about childhood autism among healthcare providers [39, 40, 57, 58, 62,63,64]. The KCAHW questionnaire has 19 items and a maximum score of 19. It is grouped into four domains: (i) social interaction; (ii) communication; (iii) circumscribed and repetitive behaviors; and (iv) autism characteristics and comorbidities [70]. A score above the mean of the KCAHW scores was considered good knowledge of autism. Nurses in Ethiopia had the lowest KCAHW mean score (8.79 ± 0.44) [62], while the highest score was reported in Kenya (14.4 ± 2.4) [64]. In Nigeria, all participants who had experience nursing children with autism achieved scores of 15 or above and psychiatric nurses outperformed pediatric nurses in all four domains of the questionnaire [57]. In Uganda, 36.1% of the participants scored below the mean (11.8 ± 3.8) [40].

Three studies in Uganda highlight the lack of knowledge among healthcare workers regarding child and adolescent mental health (CAMH) and developmental disabilities, with a significant knowledge gap regarding Tourette Syndrome [22, 28, 66]. In Nigeria, a notable lack of knowledge of child and adolescent mental illnesses was reported. Approximately 25% of the HCWs believed that child and adolescent mental illnesses could be caused by evil spells cast on a person [41], and 13% thought that such an illness could result from breaking a taboo or sinning against the gods [41].

Attitudes toward CAMH

Eight studies evaluated the attitudes of healthcare workers (HCWs) toward child and adolescent mental health (CAMH) in different countries [22, 27, 33, 41, 59, 61, 63, 65]. The findings indicate that HCWs in Ethiopia had slightly positive attitudes, but still harbored negative beliefs about children with autism [33, 59]. Health extension workers expressed doubts about the children’s ability to make their parents proud, attend school, get married in the future, and play normally with other children [33]. The other study highlighted that health extension workers’ negative attitudes and stigma act as barriers to the integration of child mental health services into primary care [59]. In Nigeria, HCWs showed poor attitudes toward CAMH, with a significant percentage believing that children with mental illness should not be allowed to play with other children [27, 41]. Up to 38% said that they would feel ashamed if someone knew that a child in their family had mental illness [41]. However, in South Africa, most of the nurses did not have negative perceptions and beliefs about the causes of autism [63].

Practices toward CAMH

Three studies indicated that HCWs’ practices toward CAMH were poor [22, 43, 68]. In Nigeria, participants expressed feelings of incompetence in managing CAMH problems [43]. Similarly, in Ethiopia, most of the participants believed that their pre-service education did not adequately prepare them to work with children with autism [68]. As a result, 66.8% of the participants felt ill-equipped to address autism and, consequently, did not provide services to children with autism [68]. Additionally, a study conducted in Uganda highlighted a significant gap in practices among HCWs concerning children with developmental disabilities, with only 148 appropriate referrals made annually, averaging 12.3 per month [22].

Other findings related to KAP on CAMH

Five studies reported that HCWs felt incompetent and lacked the confidence to deliver CAMH services [22, 35, 59, 60, 65]. In Tanzania, the participants reported changes in anxiety levels after training on adolescent depression, with 48% feeling more anxious and 43% feeling less anxious and more confident [65]. In South Africa, the health workers lacked confidence in assessment and therefore, autism is not screened for routinely or as recommended in practice [60].

Targeted interventions for CAMH

Fifteen of the 21 sources of evidence included in the review were non-interventional studies [35, 39,40,41, 43, 57, 58, 60,61,62,63,64, 66,67,68]. Six of the eligible these studies trained health professionals on CAMH and evaluated the impact of the training [22, 27, 28, 33, 59, 65]. These studies included innovative programs such as the Health Education and Training—“Mental Health: Resources for Community Health Workers” program which comprises five training videos focusing on childhood developmental problems and WHO mhGAP guidelines as well as a certified adolescent depression education program, and the Baby Ubuntu program [22, 27, 28, 33, 59, 65, 71]. The studies reported an overall increase in knowledge among the healthcare workers who participated in the training programs. Details of the training program is included in Table 1.

Discussion

Healthcare workers’ adequate knowledge, positive attitudes, and effective practices in CAMH can promote early identification and management of CAMH problems while reducing the stigma associated with seeking CAMH care services [22, 26,27,28, 43]. This scoping review mapped out the extent of literature on knowledge, attitudes, and practices toward CAMH among HCWs in SSA.

A total of 21 studies were identified, with approximately two-thirds of the studies from three countries in SSA (Uganda, Ethiopia, and Nigeria) [22, 27, 28, 33, 35, 39,40,41, 43, 57, 59, 62, 65, 66]. The findings highlight the evidence gap in the literature regarding knowledge, attitudes, and practices toward CAMH among HCWs in SSA. The lack of literature from other parts of SSA may be due to a scarcity of expertise and resources for research on this topic [72]. Increasing research efforts in SSA countries would help provide a more comprehensive understanding of CAMH [20, 69, 73].

The papers included in the review had a diverse study population. Medical doctors, nurses, clinical officers, midwives, psychologists, social workers, and community health workers were among the study participants. The diversity of the HCWs engaging in CAMH research brings together a wide range of skills, experiences, and perspectives, leading to a more integrated and effective approach to addressing CAMH challenges [2, 74]. Collaboration of the different cadres of HCWs in addressing CAMH issues has been emphasized, as it can facilitate access to child mental health services [28, 75, 76].

The most studied CAMH disorder was autism, which was reported in nearly half of the sources of evidence from Ethiopia, Uganda, and Nigeria [33, 39, 40, 57, 58, 68]. This could be due to the high prevalence of autism, which affects approximately 1 in 100 children worldwide, and the complexity of its presentation [77, 78]. Autism has a wide range of symptoms, levels of severity, and is often comorbid with other conditions. Insufficient diagnostic capacity and management of autism increases the need for more research to help address these challenges [79,80,81]. It is possible that the growing awareness and advocacy for autism, as well as increased funding from charitable organizations, have contributed to its status as one of the most studied CAMH disorders [82, 83].

A significant gap in knowledge of CAMH among healthcare workers was reported in most studies. Within studies, variations were observed in knowledge levels related to CAMH among cadres of healthcare workers [28, 40, 57, 58, 64]. Knowledge about autism was a prominent theme in the reviewed studies, with notable knowledge gaps reported. Studies conducted in Nigeria, Ghana, South Africa, Kenya, and Uganda using the KCAHW questionnaire show varied mean scores from 8.79 ± 0.44 to 14.4 ± 2.4, indicating differences in understanding of autism among healthcare workers [39, 40, 57, 58, 62,63,64]. The KCAHW scores were comparable with scores reported in similar studies conducted in Türkiye, Saudi Arabia, and Italy, with lowest scores observed in China (7.3 ± 2.19), while a study done in Sri Lanka reported a mean of 13.23 ± 2.65 [84,85,86,87,88,89]. Access to specialized training, supervision opportunities, sufficient educational curricula, and allocation of resources for capacity building in CAMH for healthcare workers varies in SSA countries. This could explain the differences in knowledge levels regarding autism among different countries in the region [18, 28, 76, 90]. Therefore, increasing awareness and education on CAMH, as well as providing targeted training programs tailored to the specific needs of different healthcare professions in the area, is necessary.

Overall, most studies reported that HCWs had poor attitudes toward CAMH [22, 27, 33, 41, 59, 65]. This attitude is not only prevalent in low-income countries but also in high-income countries such as the United Kingdom and Slovenia [91, 92]. The poor attitudes could be attributed to HCWs’ lack of knowledge about CAMH, which can lead to misconceptions and stigma toward CAMH [79]. Cultural norms and beliefs may stigmatize CAMH, leading to reluctance to seek or provide appropriate CAMH care [34, 93]. These negative beliefs and misconceptions about the causes and treatment of mental health disorders contribute to the stigma, which impedes early detection and intervention efforts [41]. However, some studies have reported positive perceptions of CAMH by healthcare workers in certain regions, for example, in South Africa, majority of the nurses did not have negative perceptions and beliefs about the causes of autism [58]. Given the complexity of changing attitudes, a more comprehensive approach involving community engagement and awareness campaigns to address cultural beliefs and reduce stigma may be needed [94, 95]. Additionally, fostering supportive work environments for HCWs and policy-level interventions related to CAMH is crucial [96,97,98]. By doing so, we can help diminish the stigma surrounding CAMH and enhance early detection and intervention efforts.

Practices toward CAMH were explored in a limited number of studies [22, 43, 59, 68, 69]. The studies have revealed a need for improvement, particularly in Nigeria and Ethiopia, where healthcare professionals were reported to have poor practices and feel ill-prepared to address CAMH disorders [43, 59]. Additionally, studies conducted in Tanzania, Ethiopia, Nigeria, and Uganda revealed that HCWs lacked confidence and competence in delivering CAMH services [22, 35, 59, 69]. Similarly, in India, doctors reported feeling unconfident in managing childhood psychiatric illnesses [99]. The scarcity of providers with specific competencies in CAMH is a global concern [100], due to the limited focus on CAMH in pre-service education programs and the lack of ongoing professional development opportunities [2, 18]. To promote CAMH services and enhance practices and competence, comprehensive training programs that address assessment, management, and referral processes are necessary [24, 75, 101, 102]. Targeted educational programs can also enhance self-confidence and competence in addressing CAMH issues [22, 103].

It is worth noting that six of the studies included reported a positive impact on HCWs’ knowledge, attitudes, and practices regarding post-CAMH-related training interventions [22, 27, 28, 33, 59, 65]. Therefore, targeted training, for example, using the mhGAP guidelines, the HEAT training, Baby Ubuntu, can effectively enhance HCWs’ understanding of CAMH-related issues and improve their attitudes and practices regarding CAMH [22, 27, 28, 59, 60, 65] and, in the future, bridge the CAMH services gap in SSA. Designing training programs on child and adolescent mental health requires careful consideration of cultural and socio-contextual factors [104]. It is crucial to acknowledge and respect cultural diversity, language barriers, and family dynamics [105]. Additionally, socioeconomic status, stigma, and discrimination can impact mental health outcomes and access to services [106]. By addressing these factors, training programs can equip the HCWs with KAP to meet the diverse needs of children, adolescents, and their families on matters CAMH in SSA.

Strengths and limitations

An extensive search was conducted, enabling the identification of a considerable number of studies. The scoping review methodology included various study designs and used a systematic approach to identifying relevant studies, charting them, and analyzing the selected study outcomes. While not required for scoping reviews, an assessment of the quality and risk of bias in the studies included enhanced the robustness of the review. The first limitation we would like to acknowledge is relying solely on the KAP framework may lead to overlooking significant aspects of mental health literacy. In contrast, frameworks like the Mental Health Literacy framework not only focus on knowledge and attitudes but also on the abilities and skills required to identify, manage, and prevent mental illness at individual and community level [46]. This approach offers a more comprehensive and results-oriented approach to mental health. Second, there are no universal cut-off scores for the KCAHW scale, a tool used to measure knowledge of autism. As a result, we relied on the guidelines provided by each author to determine the cut-off scores. For example, some studies used mean scores to categorize knowledge levels as poor or good, while others used quartiles, and this could have limited the synthesis of the included articles that used KCAHW scale.

Conclusion

In conclusion, this scoping review demonstrates the need for evidence-based targeted interventions and approaches to improve knowledge, attitudes, and practices related to CAMH among HCWs in SSA. Examples include training programs, improving educational curricula, providing ongoing training opportunities, implementing community-wide awareness campaigns, and addressing contextual factors in promoting CAMH services. By bridging the evidence gap and enhancing the capacity of HCWs, it is possible to improve CAMH outcomes and reduce the CAMH service gap in the region.

Availability of data and materials

Not applicable.

Abbreviations

- CAMH:

-

Child and Adolescent Mental Health

- HCWs:

-

Healthcare workers

- KAP:

-

Knowledge, attitudes, and practices

- KCAHW:

-

Knowledge about Childhood Autism among Health Workers

- mhGAP:

-

Mental Health Gap Action Programme

- SSA:

-

Sub-Saharan Africa

- WHO:

-

World Health Organization

References

Belfer ML. Child and adolescent mental disorders: the magnitude of the problem across the globe. J Child Psychol Psychiatry. 2008;49(3):226–36.

Kaku SM, et al. Global child and adolescent mental health perspectives: bringing change locally, while thinking globally. Child Adolesc Psychiatry Ment Health. 2022;16(1):82.

Polanczyk GV, et al. Annual research review: a meta-analysis of the worldwide prevalence of mental disorders in children and adolescents. J Child Psychol Psychiatry. 2015;56(3):345–65.

Kieling C, et al. Child and adolescent mental health worldwide: evidence for action. Lancet. 2011;378(9801):1515–25.

Bor W, et al. Are child and adolescent mental health problems increasing in the 21st century? A systematic review. Aust N Z J Psychiatry. 2014;48:606–16.

Erskine HE, et al. A heavy burden on young minds: the global burden of mental and substance use disorders in children and youth. Psychol Med. 2015;45(7):1551–63.

World Health Organization. mhGAP intervention guide for mental, neurological and substance use disorders in non-specialized health settings: mental health Gap Action Programme (mhGAP). Version 2.0 ed. Geneva: World Health Organization; 2016.

Cortina MA, et al. Prevalence of child mental health problems in sub-Saharan Africa: a systematic review. Arch Pediatr Adolesc Med. 2012;166(3):276–81.

Hunduma G, et al. Common mental health problems among adolescents in sub-Saharan Africa: a systematic review and meta-analysis. J Child Adolesc Ment Health. 2021;33(1–3):90–110.

Jörns-Presentati A, et al. The prevalence of mental health problems in sub-Saharan adolescents: a systematic review. PLoS ONE. 2021;16(5): e0251689.

Barican JL, et al. Prevalence of childhood mental disorders in high-income countries: a systematic review and meta-analysis to inform policymaking. Evid Based Ment Health. 2022;25(1):36–44.

Marangu E, et al. Assessing mental health literacy of primary health care workers in Kenya: a cross-sectional survey. Int J Ment Health Syst. 2021;15(1):55.

Dzinamarira T, et al. COVID-19 and mental health services in sub-Saharan Africa: a critical literature review. Compr Psychiatry. 2024;131: 152465.

Jenkins R, et al. Health system challenges to integration of mental health delivery in primary care in Kenya—perspectives of primary care health workers. BMC Health Serv Res. 2013;13(1):368.

Ngui EM, et al. Mental disorders, health inequalities and ethics: a global perspective. Int Rev Psychiatry. 2010;22(3):235–44.

Davids EL, et al. Child and adolescent mental health in Africa: a qualitative analysis of the perspectives of emerging mental health clinicians and researchers using an online platform. J Child Adolesc Ment Health. 2019;31(2):93–107.

Kumar M, et al. Editorial: Strengthening child and adolescent mental health (CAMH) services and systems in lower-and-middle-income countries (LMICs). Front Psychiatry. 2021;12: 645073.

Mokitimi S, Schneider M, de Vries PJ. A situational analysis of child and adolescent mental health services and systems in the Western Cape Province of South Africa. Child Adolesc Psychiatry Ment Health. 2022;16(1):6.

Sequeira M, et al. Adolescent health series: the status of adolescent mental health research, practice and policy in sub-Saharan Africa: a narrative review. Trop Med Int Health. 2022;27(9):758–66.

Bukola G, Bhana A, Petersen I. Planning for child and adolescent mental health interventions in a rural district of South Africa: a situational analysis. J Child Adolesc Ment Health. 2020;32(1):45–65.

Adugna MB, et al. Barriers and facilitators to healthcare access for children with disabilities in low and middle income sub-Saharan African countries: a scoping review. BMC Health Serv Res. 2020;20(1):15.

Sadoo S, et al. Early detection and intervention for young children with early developmental disabilities in western Uganda: a mixed-methods evaluation. BMC Pediatr. 2022;22(1):158.

Miller KK, et al. Provision of adolescent health care in resource-limited settings: perceptions, practices and training needs of Ugandan health care workers. Children Youth Serv Rev. 2022;132: 106310.

Patel V, et al. Promoting child and adolescent mental health in low and middle income countries. J Child Psychol Psychiatry. 2008;49(3):313–34.

Arzamarski C, et al. Accessing child and adolescent mental health services in low- and middle-income countries. In: Okpaku SO, editor., et al., Innovations in global mental health. Cham: Springer International Publishing; 2021. p. 971–86.

Kowalenko N, Hagali M, Hoadley B. Building capacity for child and adolescent mental health and psychiatry in Papua New Guinea. Australas Psychiatry. 2020;28(1):51–4.

Onileimo V, et al. Brief training in child and adolescent mental health: impact on the knowledge and attitudes of pediatric nurses in Nigeria. J Child Adolesc Psychiatr Nurs. 2021;34(3):164–70.

Akol A, et al. Does mhGAP training of primary health care providers improve the identification of child- and adolescent mental, neurological or substance use disorders? Results from a randomized controlled trial in Uganda. Global Ment Health. 2018;5: e29.

Kopera M, et al. Evaluating explicit and implicit stigma of mental illness in mental health professionals and medical students. Community Ment Health J. 2015;51(5):628–34.

Ramaswamy S, Sagar JV, Seshadri S. A transdisciplinary public health model for child and adolescent mental healthcare in low- and middle-income countries. Lancet Reg Health Southeast Asia. 2022;3: 100024.

World Health Organization, et al. Integrating mental health into primary care: a global perspective. Geneva: World Health Organization; 2008.

Saraceno B, et al. Barriers to improvement of mental health services in low-income and middle-income countries. Lancet. 2007;370(9593):1164–74.

Tilahun D, et al. Ethiopian community health workers’ beliefs and attitudes towards children with autism: impact of a brief training intervention. Autism. 2019;23(1):39–49.

Jansen-van Vuuren J, Aldersey HM. Stigma, acceptance and belonging for people with IDD across cultures. Curr Dev Disord Rep. 2020;7(3):163–72.

Akinyemi E, et al. Nurses and community health workers’ awareness and practices regarding child and adolescent mental health in Ekiti State, Nigeria. J Humanit Soc Sci. 2017;22:37–45.

Batty MJ, et al. Implementing routine outcome measures in child and adolescent mental health services: from present to future practice. Child Adolesc Ment Health. 2013;18(2):82–7.

World Health Organization. mhGAP intervention guide for mental, neurological and substance use disorders in non-specialized health settings: mental health Gap Action Programme (mhGAP). Geneva: World Health Organization; 2010.

World Health Organization. Mental Health Gap Action Programme (mhGAP) guideline for mental, neurological and substance use disorders. 3rd ed. Geneva: World Health Organization; 2023.

Eseigbe EE, et al. Knowledge of childhood autism and challenges of management among medical doctors in Kaduna State, Northwest Nigeria. Autism Res Treat. 2015;2015: 892301.

Namuli JD, et al. Knowledge gaps about autism spectrum disorders and its clinical management among child and adolescent health care workers in Uganda: a cross-sectional study. EC Psychol Psychiatry. 2020;9(9):112–21.

Tungchama FP, et al. Health workers’ attitude towards children and adolescents with mental illness in a teaching hospital in north-central Nigeria. J Child Adolesc Ment Health. 2019;31(2):125–37.

Adewuya AO, Oguntade AA. Doctors’ attitude towards people with mental illness in western Nigeria. Soc Psychiatry Psychiatr Epidemiol. 2007;42(11):931–6.

Oshodi Y, et al. Health care providers’ need for child and adolescent mental health (CAMH) training in South Western Nigeria. Adolesc Psychiatry. 2013;3:95–101.

Arksey H, O’Malley L. Scoping studies: towards a methodological framework. Int J Soc Res Methodol. 2005;8(1):19–32.

Daudt HML, van Mossel C, Scott SJ. Enhancing the scoping study methodology: a large, inter-professional team’s experience with Arksey and O’Malley’s framework. BMC Med Res Methodol. 2013;13(1):48.

Spiker DA, Hammer JH. Mental health literacy as theory: current challenges and future directions. J Ment Health. 2019;28(3):238–42.

Andrade C, et al. Designing and conducting knowledge, attitude, and practice surveys in psychiatry: practical guidance. Indian J Psychol Med. 2020;42(5):478–81.

Abdelrahman MA, et al. Exploration of radiographers’ knowledge, attitudes, and practices in delivering healthcare to children with autism spectrum disorder. Radiography. 2024;30(1):116–22.

Mutiso VN, et al. A step-wise community engagement and capacity building model prior to implementation of mhGAP-IG in a low- and middle-income country: a case study of Makueni County, Kenya. Int J Ment Health Syst. 2018;12(1):57.

Ahmed E, Merga H, Alemseged F. Knowledge, attitude, and practice towards mental illness service provision and associated factors among health extension professionals in Addis Ababa, Ethiopia. Int J Ment Health Syst. 2019;13(1):5.

Ndetei DM, et al. Knowledge, attitude and practice (KAP) of mental illness among staff in general medical facilities in Kenya: practice and policy implications. Afr J Psychiatry. 2011;14(3):225–35.

Paul A, et al. Knowledge, attitudes, and practices toward the novel coronavirus among Bangladeshis: implications for mitigation measures. PLoS ONE. 2020;15(9): e0238492.

Thomas J, Brunton J, Graziosi S. EPPI-Reviewer 4.0: software for research synthesis. London: Social Science Research Unit, Institute of Education, EPPI-Centre Software; 2010.

Wells GA, et al. The Newcastle–Ottawa scale (NOS) for assessing the quality of nonrandomised studies in meta-analyses. 2000.

Braun V, Clarke V. Using thematic analysis in psychology. Qual Res Psychol. 2006;3(2):77–101.

Tricco AC, et al. PRISMA extension for scoping reviews (PRISMA-ScR): checklist and explanation. Ann Intern Med. 2018;169(7):467–73.

Igwe MN, et al. Assessment of knowledge about childhood autism among paediatric and psychiatric nurses in Ebonyi state, Nigeria. Child Adolesc Psychiatry Ment Health. 2011;5(1):1.

Sampson WG, Sandra AE. Comparative study on knowledge about autism spectrum disorder among paediatric and psychiatric nurses in public hospitals in Kumasi, Ghana. Clin Pract Epidemiol Ment Health. 2018;14:99–108.

Tilahun D, et al. Training needs and perspectives of community health workers in relation to integrating child mental health care into primary health care in a rural setting in sub-Saharan Africa: a mixed methods study. Int J Ment Health Syst. 2017;11(1):15.

Matlou M. Screening, diagnosis and management of autism spectrum disorders amongst healthcare practitioners in South Africa. In: Paediatrics and child health. Bloemfontein: University of the Free State; 2021.

Muke K, et al. Knowledge attitude and practice (KAP) survey among healthcare professionals in pediatrics on the psychomotor development of children. Case of urban and rural health areas in South Kivu in the Democratic Republic of Congo: a cross-sectional study. Ann Med Surg. 2023;85(8):3863–9.

Tasew S, Mekonnen H, Goshu AT. Knowledge of childhood autism among nurses working in governmental hospitals of Addis Ababa, Ethiopia. SAGE Open Med. 2021;9:20503121211049120.

Williams N. The knowledge, understanding and perceptions of professional nurses, working in primary health care clinics, about autism spectrum disorder, in health sciences. Durban University of Technology: DUT Open Scholar; 2018.

Fatma Z. Assessment of knowledge and practice about childhood autism among health care workers at Kenyatta National Hospital, in Faculty of Health Sciences. The University of Nairobi: UoN Digital Repository; 2021.

Kutcher S, et al. Addressing adolescent depression in Tanzania: positive primary care workforce outcomes using a training cascade model. Depress Res Treat. 2017;2017:9109086.

Rodin A, et al. Why don’t children in Uganda have tics? A mixed-methods study of beliefs, knowledge, and attitudes of health professionals. Child Adolesc Ment Health. 2021;26(1):47–53.

Sheriff B, et al. Knowledge of developmental disabilities and referral sources among health workers in two Ghanaian hospitals. Int J Dev Disabil. 2022;70:1–11.

Zeleke WA, Hughes TL, Kanyongo G. Assessing the effectiveness of professional development training on autism and culturally responsive practice for educators and practitioners in Ethiopia. Front Psychiatry. 2020;11: 583674.

Kutcher S, et al. Creating evidence-based youth mental health policy in sub-Saharan Africa: a description of the integrated approach to addressing the issue of youth depression in Malawi and Tanzania. Front Psychiatry. 2019;10:542.

Bakare MO, et al. Knowledge about childhood autism among health workers (KCAHW) questionnaire: description, reliability and internal consistency. Clin Pract Epidemiol Ment Health. 2008;4:17.

Nanyunja C, et al. Early care and support for young children with developmental disabilities and their caregivers in Uganda: the Baby Ubuntu feasibility trial. Front Pediatr. 2022;10: 981976.

Abubakar A, Ssewanyana D, Newton CR. A systematic review of research on autism spectrum disorders in sub-Saharan Africa. Behav Neurol. 2016;2016:3501910.

Mabrouk A, et al. Mental health interventions for adolescents in sub-Saharan Africa: a scoping review. Front Psychiatry. 2022;13: 937723.

Rukundo GZ, et al. A collaborative approach to the development of multi-disciplinary teams and services for child and adolescent mental health in Uganda. Front Psychiatry. 2020;11: 579417.

Patel V, et al. Improving access to care for children with mental disorders: a global perspective. Arch Dis Child. 2013;98(5):323–7.

Raj V, et al. Child and adolescent mental health training programs for non-specialist mental health professionals in low and middle income countries: a scoping review of literature. Community Ment Health J. 2022;58(1):154–65.

Zeidan J, et al. Global prevalence of autism: a systematic review update. Autism Res. 2022;15(5):778–90.

Masi A, et al. An overview of autism spectrum disorder, heterogeneity and treatment options. Neurosci Bull. 2017;33(2):183–93.

Jarso MH, et al. Knowledge, attitude, and its correlates of the community toward mental illness in Mattu, South West Ethiopia. Front Psychiatry. 2022;13:1018440.

Lord C, et al. Autism spectrum disorder. Lancet. 2018;392(10146):508–20.

Waizbard-Bartov E, et al. Autism severity and its relationship to disability. Autism Res. 2023;16(4):685–96.

Tekola B, et al. Challenges and opportunities to improve autism services in low-income countries: lessons from a situational analysis in Ethiopia. Global Ment Health. 2016;3: e21.

Aderinto N, Olatunji D, Idowu O. Autism in Africa: prevalence, diagnosis, treatment and the impact of social and cultural factors on families and caregivers: a review. Ann Med Surg. 2023;85(9):4410–6.

Kilicaslan F, et al. Knowledge about childhood autism among nurses in family health centers in southeast Turkey. Int J Dev Disabil. 2022. https://doi.org/10.1080/20473869.2022.2149063.

Yılmaz Z, Al-Taie A. A cross-sectional study of community pharmacists’ self-reported disease knowledge and competence in the treatment of childhood autism spectrum disorder. Int J Clin Pharm. 2023;45(5):1088–97.

Corsano P, Cinotti M, Guidotti L. Paediatric nurses’ knowledge and experience of autism spectrum disorders: an Italian survey. J Child Health Care. 2020;24(3):486–95.

Hayat AA, et al. Assessment of knowledge about childhood autism spectrum disorder among healthcare workers in Makkah-Saudi Arabia. Pak J Med Sci. 2019;35(4):951–7.

Rohanachandra YM, Prathapan S, Amarabandu HGI. The knowledge of public health midwives on autism spectrum disorder in two selected districts of the Western Province of Sri Lanka. Asian J Psychiatr. 2020;52: 102094.

Zhang X, et al. Child healthcare workers’ knowledge about autism and attitudes towards traditional Chinese medical therapy of autism: a survey from grassroots institutes in China. Iran J Pediatr. 2018;28(5): e60114.

Galagali PM, Brooks MJ. Psychological care in low-resource settings for adolescents. Clin Child Psychol Psychiatry. 2020;25(3):698–711.

Pintar Babič M, Bregar B, Drobnič Radobuljac M. The attitudes and feelings of mental health nurses towards adolescents and young adults with nonsuicidal self-injuring behaviors. Child Adolesc Psychiatry Ment Health. 2020;14(1):37.

Dickinson T, Hurley M. Exploring the antipathy of nursing staff who work within secure healthcare facilities across the United Kingdom to young people who self-harm. J Adv Nurs. 2012;68(1):147–58.

Subu MA, et al. Types of stigma experienced by patients with mental illness and mental health nurses in Indonesia: a qualitative content analysis. Int J Ment Health Syst. 2021;15(1):77.

Mascayano F, et al. Including culture in programs to reduce stigma toward people with mental disorders in low- and middle-income countries. Transcult Psychiatry. 2019;57(1):140–60.

Stuart H. Reducing the stigma of mental illness. Global Ment Health. 2016;3: e17.

Jenkins R. Supporting governments to adopt mental health policies. World Psychiatry. 2003;2(1):14–9.

Søvold LE, et al. Prioritizing the mental health and well-being of healthcare workers: an urgent global public health priority. Front Public Health. 2021;9: 679397.

Zhou W, et al. Child and adolescent mental health policy in low- and middle-income countries: challenges and lessons for policy development and implementation. Front Psychiatry. 2020;11:150.

Mina S, Goyal S, Verma R. Doctors’ perspective, knowledge, and attitude toward childhood psychiatric illnesses. Indian J Soc Psychiatry. 2018;34(3):203–7.

Delaney KR, Karnik NS. Building a child mental health workforce for the 21st century: closing the training gap. J Prof Nurs. 2019;35(2):133–7.

Srinath S, et al. Clinical practice guidelines for assessment of children and adolescents. Indian J Psychiatry. 2019;61(Suppl 2):158–75.

Wiedermann CJ, et al. Fortifying the foundations: a comprehensive approach to enhancing mental health support in educational policies amidst crises. Healthcare. 2023;11(10):1423.

Weiss B, et al. A model for sustainable development of child mental health infrastructure in the LMIC world: Vietnam as a case example. Int Perspect Psychol. 2012;1(1):63–77.

Gopalkrishnan N. Cultural diversity and mental health: considerations for policy and practice. Front Public Health. 2018;6:179.

Alegria M, et al. One size does not fit all: taking diversity, culture and context seriously. Adm Policy Ment Health. 2010;37(1–2):48–60.

Pumariega AJ, Rogers K, Rothe E. Culturally competent systems of care for children’s mental health: advances and challenges. Community Ment Health J. 2005;41(5):539–55.

Acknowledgements

We would like to thank Michael Kariuki for his contribution to creating the map highlighting the SSA countries included in the review.

Funding

This research was commissioned by the National Institute for Health and Care Research (NIHR) (NIHR200842) using UK aid from the UK Government. The views expressed in this publication are those of the author(s) and not necessarily those of the NIHR or the Department of Health and Social Care. The funder has no involvement in the design, data collection, analysis, data interpretation or development of manuscripts linked to the project.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

A.A. and C.R.N. conceptualized and obtained funding for the study. B.M., A.A., M.S., and V.A. provided input on the study design and methodology. B.M. performed the database search. B.M. and B.N. independently screened the articles and performed data extraction for the studies included. B.M. analyzed the findings of the studies included and drafted the review report. A.A., M.S., and V.A. provided guidance throughout the process. All authors contributed to the drafting and review of the manuscript. B.M.’s ORCID iD: 0000-0002-2058-3325.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate

Not applicable.

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary Information

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/. The Creative Commons Public Domain Dedication waiver (http://creativecommons.org/publicdomain/zero/1.0/) applies to the data made available in this article, unless otherwise stated in a credit line to the data.

About this article

Cite this article

Mkubwa, B., Angwenyi, V., Nzioka, B. et al. Knowledge, attitudes, and practices on child and adolescent mental health among healthcare workers in sub-Saharan Africa: a scoping review. Int J Ment Health Syst 18, 27 (2024). https://doi.org/10.1186/s13033-024-00644-8

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/s13033-024-00644-8