Abstract

Background

Anxious-depressive attack (ADA) is a symptom complex that comprises sudden intense feelings of anxiety or depression, intrusive rumination of regretful memories or future worries, emotional distress due to painful thoughts, and coping behaviors to manage emotional distress. ADA has been observed trans-diagnostically across various psychiatric disorders. Although the importance of ADA treatment has been indicated, a scale to measure the severity of ADA has not been developed. This study aimed to develop an Anxious-Depressive Attack Severity Scale (ADAS) to measure the severity of ADA symptoms and examine its reliability and validity.

Methods

A total of 242 outpatients responded to a questionnaire and participated in an interview, which were designed to measure the severity of ADA, depressive, anxiety, anxious depression, and social anxiety symptoms. Based on the diagnostic criteria for ADA, 54 patients were confirmed to have ADA and were included in the main study analyses.

Results

The exploratory factor analysis of the ADAS identified a two factor structure: severity of ADA symptoms and ADA frequency and coping behaviors. McDonald’s ωt coefficients were high for the overall scale and the first factor (ωt = .78 and ωt = .83, respectively) but low for the second factor (ωt = .49). The ADAS score was significantly positively correlated with clinical symptoms related to anxiety and depression.

Conclusion

The present study demonstrated that the ADAS has sufficient reliability and validity; however, internal consistency was insufficient for the second factor. Overall, the ADAS has potential to be a valuable tool for use in clinical trials of ADA.

Similar content being viewed by others

Background

Anxious-depressive attack (ADA) is a novel cluster of symptoms that include abrupt outbursts of anxiety or depression, intrusive rumination of negative memories or future worries (with or without flashbacks), intense emotional distress that is caused by recalling painful details of past memories or anticipatory concerns, and a wide range of violent coping behaviors for emotional distress, including self-harm and overdosing [1]. There is no direct psychological cause of ADA, and it is thought to be a psychological form of a panic attack.

Table 1 shows the diagnostic criteria of ADA [2]. ADA differs from panic attacks. It does not include intense physical symptoms such as those observed in panic disorder, and its core symptoms include severe anxiety, intrusive rumination or worry, and emotional distress caused by these thoughts. The attack also exhibits negative feelings such as depression, sadness, self-hatred, emptiness, helplessness, anxious-irritable feelings, and loneliness [1]. Indeed, ADA is a trans-diagnostic symptom complex in patients with various anxiety disorders as well as mood disorders [1, 3]. ADA frequency has been shown to be correlated with the severity of social anxiety and depressive symptoms [1]. In a previous study of patients with social anxiety disorder, the relation between ADA, social anxiety, depressive symptoms, and rejection sensitivity was examined using structural equation modeling [2]. The results showed that ADA was directly affected by rejection sensitivity and depressive symptoms and indirectly affected by social anxiety symptoms via depressive symptoms.

The prevalence of ADA in new patients visiting clinics solely for anxiety and mood disorders was estimated as 16.88% [4], which indicates that ADA is not a rare symptom complex. Furthermore, ADA generally has a refractory and chronic nature requiring treatment [1, 3]. Although a questionnaire to confirm the presence of ADA has been developed [1], a scale to measure the severity of ADA symptom has not. Therefore, the present study aimed to develop an Anxious-Depressive Attack Severity Scale (ADAS). We examined the reliability and validity of the ADAS by correlating the scores with severity of depressive, anxiety, anxious depression, and social anxiety symptoms.

Methods

Participants

Participants were outpatients who visited clinics solely for anxiety and depression in Tokyo and Yokohama and were aged ≥16 years. Exclusion criteria included high suicide risk, severe physical illness, and significant cognitive impairment. After obtaining written informed consent, 242 outpatients participated in a survey. Of these, 54 patients (10 men and 44 women) were confirmed to have experienced ADA according to the diagnostic criteria of ADA (Table 1). The age of participants ranged from 16 to 78 years, with a mean age of 33.67 (standard deviation [SD] = 13.17) years. Table 2 summarizes the clinical characteristics of the participants with ADA according to a Mini-International Neuropsychiatric Interview (MINI: [5, 6]) conducted by clinical psychologists.

This study was approved by the ethics committee of the first author’s affiliated institution.

Measures

The ADAS was developed to assess the severity of ADA symptoms. We developed seven items to measure the severity of ADA symptoms. These items included four symptoms (Item 1, Diagnostic Criteria B-1: sudden intense feelings of anxiety or depression; Item 2, Diagnostic Criteria B-2: intrusive rumination of regretful memories or future worries; Item 3, Diagnostic Criteria B-3: emotional distress caused by painful thoughts; and Item 4, Diagnostic Criteria B-4: coping behaviors to manage emotional distress) based on the diagnostic criteria of ADA (Table 1). We also added items focusing on ADA frequency and duration according to the study by Kaiya [1]. We included an item on the overall ADA severity to measure the overall severity of symptoms, including the patient’s subjective pain and impairment in life. The seven items are listed in Table 3. The ADAS was administered using the structured interview method.

During the ADAS interview session, five psychological batteries were also administered. The Hamilton Depression Rating Scale (HAM-D: [7, 8]) consists of 17 items and is one of the most widely used scales for the assessment of depressive symptoms. The scale covers the whole spectrum of depressive symptoms, which includes affective, cognitive, and somatic symptoms. Items are scored from 0 to 4 (absent, mild or trivial, moderate, and severe) or 0 to 2 (absent, slight or doubtful, and clearly present). The total score ranges from 0 to 54, with higher scores representing greater severity of depressive symptoms.

The Hamilton Anxiety Rating Scale (HAM-A: [9, 10]) consists of 14 items and is one of the most widely used scales for assessing anxiety symptoms in research settings. Items are scored from 0 to 4 (not present, mild, moderate, severe, and very severe). The total score ranges from 0 to 56, with higher scores indicating greater severity of anxiety symptoms.

The Quick Inventory of Depressive Symptomatology (QIDS: [11, 12]) measures nine symptom domains of depression. The total score ranges from 0 to 27, with higher scores representing higher severity of depressive symptoms.

The Anxious Depression Scale (ADS: [13]) measures anxious depression symptoms in patients with depressive disorder with atypical features. It is a self-reported measure comprising 20 items and consists of 4 factors: behavioral/emotional symptoms, physical symptoms, aggressive emotions, and nonaggressive emotions. Items are scored from 1 to 4 (not at all, sometimes, mostly, and very much) and the total score ranges from 20 to 80.

The Liebowitz Social Anxiety Scale (LSAS: [14, 15]) was originally developed as a clinician-administered scale to assess the range of social interactions and performance situations feared by patients to help diagnose social anxiety disorder. It was subsequently validated as a self-report inventory comprising 24 items, which are each scored on two 4-point Likert scales for level of fear and frequency avoidance during situations, such as “telephoning in public.” The total score ranges from 0 to 144.

Statistical analyses

First, an exploratory factor analysis (EFA) using principal component analysis (Promax rotation) was conducted to determine the factor structure of the ADAS. Second, item-total correlation and McDonald’s ωt coefficients for the ADAS were computed to examine reliability. Third, to examine the criteria-related validity of the ADAS, we computed Pearson’s correlation coefficients between the ADAS and the HAM-D, HAM-A, QIDS, ADS, and LSAS. SPSS version 25 (IBM Corp., Armonk, NY, USA) was used to conduct the EFA and correlation analyses. R version 4.0.2 was used to compute McDonald’s ωt coefficients and to conduct a parallel analysis.

Results

EFA

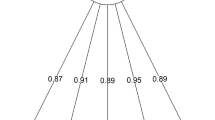

The Kaiser–Meyer–Olkin (KMO) measure of sampling adequacy was .639 (KMO value ≥ .60); thus, the data were suitable for factor analysis [16]. Bartlett’s test of sphericity was significant (p < .01). The eigenvalues of the first, second, third, fourth, and fifth components were 3.01, 1.31. 1.12, .60, and .54, respectively. Three factors were determined using the Kaiser criterion, two factors by the scree plot, and two factors by the parallel analysis results. Based on these indices, two-factor and three-factor structure were assumed and factor analyses were conducted. The results showed that the three-factor structure had a factor with only one item and the three items had factor loadings greater than .30 for two or more factors. Therefore, the two-factor model was found to be the most interpretable solution. The EFA results showed that the ADAS had a two-factor structure, with five items in the first factor (severity of ADA symptoms) and two items in the second factor (ADA frequency and coping behaviors; Table 4).

Item-total correlations and internal consistency

The results of the item-total correlation analyses showed that there were moderate to strong positive correlations between the total score and each item of the ADAS (r = .45–.79, p < .01) (Table 4). Furthermore, McDonald’s ωt coefficients were high for the overall scale and first factor (ωt = .78, ωt = .83) and low for the second factor (ωt = .49).

Criterion-related validity

The ADAS total score was significantly and positively correlated with HAM-D, HAM-A, QIDS, ADS, and LSAS scores (p < .05; Table 5). The first factor of the ADAS showed significant and positive correlations with HAM-D, QIDS, ADS, and LSAS scores (p < .05), but not with the HAM-A score. The second factor of the ADAS showed significant positive correlations with HAM-D and HAM-A scores (p < .05), but not with QIDS, ADS, and LSAS scores.

Discussion

The goal of the present study was to develop the ADAS and examine its reliability and validity. The EFA showed that the ADAS had a two-factor structure: “severity of ADA symptoms” factor (five items) and “ADA frequency and coping behaviors” factor (two items). The severity of ADA symptom (the first factor) was strongly related to the intrusive rumination of regretful memories or future worries and the emotional distress caused by painful thoughts. The ADA frequency and coping behaviors (the second factor) consisted of ADA frequency and coping behaviors to manage emotional distress. Furthermore, the correlation coefficients between each item and the total score ranged from .45 to .79. McDonald’s ωt coefficients of the ADAS for the overall scale and first factor were higher than .75, which indicated high internal consistency. However, the ωt coefficient for the second factor was low. There were only two items in the second factor, which may have contributed to the low ωt coefficient.

The criterion-related validity of the ADAS was assessed by examining whether or not the ADAS scores correlated with clinical indices that are associated with ADA. The ADAS showed significant positive correlations with the severity of depressive, anxiety, anxious depression, and social anxiety symptoms, and these results are similar to those observed in previous studies [1,2,3]. Hence, the ADAS has criterion-related validity. These findings suggested that the ADAS is a reliable and valid tool for assessing the severity of ADA.

As shown in Table 2, ADA is predominantly observed in patients with depression and/or anxiety disorders. ADA was identified in 43.14, 33.33, 23.53, and 19.61% of patients with major depressive episodes, agoraphobia and generalized anxiety disorder, social anxiety disorder, and current panic disorder, respectively. Therefore, ADA is a trans-diagnostic symptom complex, particularly those occurring in anxiety and depressive disorders.

Previous studies have highlighted the importance of treating ADA and the need for ADA assessment tool [1, 3]. The ADAS findings in this study showed that many patients had moderate-to-severe ADA symptoms. In item 7, which assesses the severity of overall ADA, the mean score was 2.33: total score 3, and 27 of 54 patients fell into the severe category (score 3). Thus, many patients suffer from ADA symptoms and require treatment. ADAS will enable the accurate assessment of the degree of ADA symptoms and could be a useful screening tool for patients requiring ADA treatment. ADAS is also expected to contribute to the understanding of the ADA pathology. Future studies are required to examine the relation between the severity of ADA symptoms as measured by ADAS and psychological, physiological, and social indicators.

However, there are some limitations to this study that need to be considered. The internal consistency for the second factor (ADA frequency and coping behaviors factor) was low. The number of items in the second factor should be increased to improve the internal consistency. On achieving improvement, a priori power calculations should be performed and then cross-validity should be assessed in a larger sample of patients for more reliable results. A longitudinal study that evaluates ADAS sensitivity to change would also be useful.

Conclusions

In the present study, our newly developed ADAS was shown to be a reliable and valid instrument for assessing the severity of ADA. The ADAS can be a valuable tool for use in clinical trials of ADA.

Availability of data and materials

Detailed data are available from the corresponding authors upon reasonable request.

Abbreviations

- ADA:

-

Anxious-depressive attack

- ADAS:

-

Anxious-Depressive Attack Severity Scale

- HAM-D:

-

Hamilton depression rating scale

- HAM-A:

-

Hamilton anxiety rating scale

- QIDS:

-

Quick inventory of depressive symptomatology

- ADS:

-

Anxious depression scale

- LSAS:

-

Liebowitz social anxiety scale

- SD:

-

Standard deviation

References

Kaiya H. Distinctive clinical features of “anxious-depressive attack”. Anxiety Disord Res. 2017;9(1):2–16. https://doi.org/10.14389/jsad.9.1_2.

Kaiya H, Noda S, Takai E, Fukui I, Masaki M, Matsumoto S, et al. Effects of rejection sensitivity on the development of anxious-depressive attack in patients with social anxiety disorder. Anxiety Disord Res. 2020;12(1):37–44. https://doi.org/10.14389/jsad.12.1_37.

Kaiya H. Anxious-depressive attack—an overlooked condition—a case report. Anxiety Disord Res. 2016;8(1):22–30. https://doi.org/10.14389/jsad.8.1_22.

Matsumoto S, Mina M, Komatsu C, Noguchi K, Kawasaki N, Kishino Y, et al. Examination of the prevalence of anxious-depressive attacks in new outpatients. Hyogo: Abstract of the 12th Japanese Society of Anxiety and Related Disorders Academic Conference; 2020. (In Japanese)

Otsubo T, Miyaoka H, Kamijima K. MINI: brief diagnostic structured interview for mental disease. Tokyo: Seiwa Shoten Publishers; 2000. (In Japanese)

Sheehan DV, Lecrubier Y, Sheehan KH, Amorim P, Janavs J, Weiller E. The MINI-international neuropsychiatric interview (MINI): the development and validation of a structured diagnostic psychiatric interview for DSM-IV and ICD-10. J Clin Psychiatry. 1998;59:22–33.

Hamilton M. A rating scale for depression. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry. 1960;23(1):56–62. https://doi.org/10.1136/jnnp.23.1.56.

Nakane Y, Williams JBW. Japanese version of structured interview guide for the Hamilton depression rating scale (SIGH-D). Tokyo: Seiwa Shoten Publishers; 2014. (In Japanese)

Otsubo T, Koda R, Takashio O, Tanaka K, Eto R, Owashi T, et al. Reliability and validity of the Japanese version of Hamilton anxiety rating scale-interview guide. Jpn J Clin Psychopharmacol. 2005;8:1579–93 (In Japanese).

Hamilton M. The assessment of anxiety states by rating. Br J Med Psychol. 1959;32(1):50–5. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.2044-8341.1959.tb00467.x.

Fujisawa D, Nakagawa A, Tajima M, Sado M, Kikuchi T, Iba M, et al. Cross-cultural adaptation of the quick inventory of depressive symptomatology-self report (QIDS-SR-J). Jpn J Stress Sci. 2010;25:43–52 (In Japanese).

Rush AJ, Trivedi MH, Ibrahim HM, Carmody TJ, Arnow B, Klein DN, et al. The 16-item quick inventory of depressive symptomatology (QIDS), clinician rating (QIDS-C), and self-report (QIDS-SR): a psychometric evaluation in patients with chronic major depression. Biol Psychiatry. 2003;54(5):573–83. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0006-3223(02)01866-8.

Suyama H, Yokoyama C, Komatsu C, Noguchi K, Kaneko Y, Suzuki S, et al. Development and validation of an anxious depression scale (ADS). Jpn J Behav Ther. 2013;39:87–97 (In Japanese).

Asakura S, Inoue S, Sasaki F, Sasaki Y, Kitagawa N, Inoue T, et al. Reliability and validity of the Japanese version of the Liebowitz social anxiety scale. Jpn J Psychiatr Med. 2002;44:1077–84 (In Japanese).

Liebowitz, MR. Social phobia. Mod Probl Pharmacopsychiatry. 1987;22:141-73. New York: Karger. https://www.karger.com/Article/Abstract/414022#, https://doi.org/10.1159/000414022.

Field A. Discovering statistics using IBM SPSS statistics. 5th ed. London: SAGE Publications; 2018.

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to thank Enago for the English language review.

Note

The ADAS is available upon request to the sixth author (kai@fuanclinic.com).

Funding

Not applicable.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

HK prepared ADAS and organized the study. Data collection was performed by SN, HK, SM, and NK. SN and HK designed the methods and wrote the first draft of the manuscript. IF revised the draft of the manuscript. All authors approved the final version of the manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate

This study was approved by the ethics committee of the first author’s affiliated institution.

Consent for publication

Written informed consent was obtained from all participants prior to their enrollment in the study.

Competing interests

The authors have no competing interests to declare.

Additional information

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/. The Creative Commons Public Domain Dedication waiver (http://creativecommons.org/publicdomain/zero/1.0/) applies to the data made available in this article, unless otherwise stated in a credit line to the data.

About this article

Cite this article

Noda, S., Matsumoto, S., Kawasaki, N. et al. The anxious-depressive attack severity scale: development and initial validation and reliability. BioPsychoSocial Med 15, 12 (2021). https://doi.org/10.1186/s13030-021-00214-1

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/s13030-021-00214-1