Abstract

The majority of Halicephalobus gingivalis-infections in horses have been fatal and are usually not diagnosed before necropsy. Therefore, knowledge about the nematode and the pathogenesis of infection in horses is limited. This has resulted in an on-going discussion about the port of entry and subsequent dissemination of H. gingivalis within the host. The present case of H. gingivalis-infection in a horse was diagnosed ante mortem. Post mortem findings, the distribution pattern of H. gingivalis nematodes in the brain, a high prevalence of inflammation in close relation to blood vessels, and the presence of the nematode in multiple organs with a disseminated pattern of distribution strongly suggested a haematogenous spread of the nematode in the horse.

Similar content being viewed by others

Background

Halicephalobus gingivalis is a free-living nematode belonging to the order Rhabditida and family Panagrolaimidae [1]. H. gingivalis is a facultative parasite of humans and horses and more than five cases in humans and 65 cases in horses have been reported [2] since the infection was described for the first time by Stefanski in 1954 [3]. The majority of infections have been fatal and in most cases the diagnosis was stated post mortem. In horses, H. gingivalis mainly infects the brain, kidneys, mandible and maxillary bones and the eyes where it causes a granulomatous inflammation [4]-[6]. In single cases, the nematode has been found histologically in the heart, blood vessels, testicles, femur, lymph nodes, parathyroid glands and preputium [2],[5],[7]. There is an on-going discussion about the pathogenesis of the nematode, especially concerning the spreading following penetration into the body. Different theories including haematogenous [4]-[6] and lymphogenic [4] spread and tissue migration [8],[9] have been proposed.

An equine case of H. gingivalis infection was recently diagnosed at the University of Copenhagen, and lesions in various organs were strongly supportive of a haematogenous dissemination of the nematode.

Case presentation

In July 2012, an 11-year-old Icelandic horse stallion with a history of fever and unilateral facial swelling was admitted to the University Hospital for Large Animals. Clinically, the horse had bilaterally enlarged mandibular lymph nodes and a bony proliferation above the maxillary sinus. Bilateral opening of the maxillary sinuses was performed with a bone flap technique at standing surgery [10]. Large amounts of granulation tissue like masses filled most of the caudal and rostral parts of the left maxillary sinus. The masses were debrided extensively and tissue samples fixed in 10% neutral buffered formalin, embedded in paraffin wax and sectioned at 4 μm. Sections were stained with haematoxylin and eosin (HE). Histologically, large numbers of concentric pyogranulomatous foci with centrally placed H. gingivalis-like nematodes were observed. Moreover, tissues samples were examined for parasites by the Baermann method [11] by which several adult H. gingivalis nematodes were identified based on morphological appearance [1]. Only female specimens were identified.

The horse was treated with a second sinus surgery, where the flap was reopened and the sinuses packed with gauze soaked in ivermectin. Postoperatively, sinuses were flushed with ivermectin once a day through trephination holes. Additionally, the horse received fenbendazole at twice the recommended dosage (15 mg/kg) once a day for 5 consecutive days and auxiliary therapy with penicillin (22 000 IU/kg), flunixin meglumine (1.1 mg/kg), dexamethasone (0.1 mg/kg), omeprazole (1 mg/kg), as well as fluid and pain medication as needed.

The horse developed severe neurological signs (ataxia and blindness), which progressed over the next week. Due to the lack of response to treatment and the grave prognosis, the horse was euthanized and a post mortem computed tomography (CT) scanning of the head only revealed lesions within the sinuses. The horse was subjected to a complete necropsy, and following removal of the brain, the head was sagitally sectioned at different levels. The observed granulation tissue-like masses in the left rostral and caudal maxillary sinuses had caused a marked compression of the nasal cavity.

In addition to the sinus lesions, macroscopic renal lesions were found. These were seen as multiple disseminated, yellow-grey nodules with a diameter of 1.0 to 1.5 cm protruding from the surface of both kidneys.

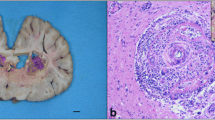

For histology, the brain was sampled in toto together with tissue specimens from the sinuses, kidneys, lungs, liver, eyes, and spleen. The samples were processed as described above and sections were stained with HE. As illustrated in Figure 1, a total of 12 samples were taken from the brain, and in all sections some degree of inflammation was seen in the meninges and brain parenchyma. Lesions were mainly observed in the midbrain (Figure 2). In the brain parenchyma, lesions were typically localized just beneath the meningeal lining or in relation to blood vessels (Figure 3). In the meninges, mild to severe inflammation was observed with infiltration of macrophages, multinucleate giant cells, lymphocytes as well as few plasma cells and eosinophils. In some areas, infiltration with neutrophils was present as well. The inflammatory reactions were mainly localized in relation to blood vessels but more diffuse infiltrations were also seen. Similar lesions were present in the brain tissue together with perivascular cuffs. In relation to the inflammatory reactions of the meninges and brain tissue, graded as mild, moderate and severe?=?1, 2 and 3 (see Figure 2), numerous nematodes of all stages from eggs to adults, with an identical morphology to those present in the sinusoidal tissue masses, were present.

Brain section of equine brain with the sample numbers (1–12) taken for histology. In Figure 2 the degree of inflammation in relation to the 12 samples/areas of the brain is illustrated.

The degree of inflammation (mild?=?1, moderate?=?2, and severe?=?3) in relation to the 12 sample sites, see Figure 1 .

In sample number 4 from the left hemisphere, a mature female nematode with dorso flexed ovary (?) is located in the brain tissue (inserted) just beneath the meninges. The nematode is accompanied by macrophages in the brain tissue and a mild infiltration of mononuclear cells in the leptomeninges. HE. Bar = 100 μm.

In both kidneys, a high density of parasites with the same characteristics as the nematodes in the meninges, brain and sinuses were found. The inflammatory reaction of the kidneys was similar to that in the sinuses, i.e. formation of concentric foci with nematodes localized centrally and surrounded by epithelioid cells, macrophages, multinucleated giant cells, lymphocytes, and occasionally eosinophils.

Conclusions

The present case is comparable to other cases of equine H. gingivalis-infection [5], and the nematode was identified both in the histological samples of different organs and with subsequent isolation and identification. Knowledge about the nematode and infection of horses is limited due to the relative low number of reported cases and presumably because the infection is rarely diagnosed ante mortem. Moreover, reported clinical manifestations in horses with H. gingivalis- infections are highly variable, complicating any possible conclusions regarding the port of entry and subsequent dissemination of the parasite within the host. Consequently, this has given rise to an on-going discussion about this subject. However, during recent years the infection has been diagnosed in countries worldwide [2], and the growing number of reported cases has created a clearer picture of the route of infection and the distribution pattern of nematodes in horses. Several studies suggest that penetration of mucosal membranes or the skin is the most likely port of entry [7],[8],[12]-[14].

Nematodes are often found in various parts of the brain and meninges, and the high occurrence of neurological manifestations in horses with H. gingivalis-infection is probably caused by a high affinity for the meninges and brain tissue. This was confirmed in our study where inflammation and nematodes were found in a pattern of distribution as seen in animal models focusing on the localization and distribution of brain abscesses following challenge with Staphylococcus aureus[15]. The pattern of distribution of meningeal and brain lesions together with a high prevalence of inflammation and presence of nematodes in relation to blood vessels strongly suggest, that H. gingivalis was spread haematogenously to the brain and meninges in this case. This pathogenesis is supported by others, who observed the nematode close to blood vessels, and occasionally in the heart [13], and within the wall of blood vessels [13],[14]. Although H. gingivalis has been isolated from urine and semen [16], it remains to be found in blood samples. A haematogenous mode of dissemination was also supported by the presence of bilateral and disseminated lesions in the kidneys, which have also frequently been reported by others [2],[4],[14],[16].

The fact that nematodes occasionally were found in the brain parenchyma just beneath infected meningeal tissue indicates that some degree of local migration may occur. Histologically, all lesions were chronic and contained a high number of reproducing mature nematodes, which might give rise to the formation of new focal infection sites, just not visible macroscopically. H. gingivalis does not always cause gross lesions. It is occasionally found in other organs, e.g. in a macroscopically normal parathyroid gland of a horse with a suspected diagnosis of dystrophia fibrosa [2]. Moreover, as observed in the present case, the application of CT scan is often not helpful in order to disclose lesions not being apparent at gross inspection [17].

Authors’ contributions

CH evaluated the clinical and pathological observations and drafted the manuscript. AJ and HEJ did the necropsy and histopathological evaluations. SJ performed the clinical examinations and surgery. MKN identified the parasite. FM evaluated the CT scans and helped to draft the manuscript. All authors have read and accepted the final version of the manuscript.

References

Anderson RC, Linder KE, Peregrine AS:Halicephalobus gingivalis (Stefanski, 1954) from a fatal infection in a horse in Ontario, Canada with comments on the validity of H. deletrix and a review of the genus. Parasite. 1998, 5: 255-261. 10.1051/parasite/1998053255.

Henneke C, Jespersen A, Jacobsen S, Olsen SN, Nielsen MK, McEvoy F, Jørgensen B, Jensen HE:Halicephalobus gingivalis – infektion hos hest. Dansk Vettidsskr. 2014, 2: 22-26.

Stefanski W:Rhabditis gingivalis sp. n. parasite trouvé dans un granulome de la gencive chez un cheval. Acta Parasitol Polonica. 1954, 1: 329-334.

Akagami M, Shibahara T, Yoshiga T, Tanaka N, Yaguchi Y, Onuki T, Kondo T, Yamanka T, Kubo M: Granulomatous nephritis and meningoencephalomyelitis caused by Halicephalobus gingivalis in a pony gelding. J Vet Med Sci. 2007, 69: 1187-1190. 10.1292/jvms.69.1187.

Hermosilla C, Coumbe KM, Habershon-Butcher J, Schöniger S: Fatal equine meningoencephalitis in the United Kingdom caused by the panagrolaimid nematode Halicephalobus gingivalis: case report and review of the literature. Eq Vet J. 2011, 43: 759-763. 10.1111/j.2042-3306.2010.00332.x.

Sant’Ana FJFD, Ferreira JA, Costa YLD, Resende RMD, Barros CSL: Granulomatous meningoencephalitis due to Halicephalobus gingivalis in a horse. Braz J Vet Pathol. 2012, 5: 12-15.

Dunn DG, Gardiner CH, Dralle KR, Thilsted JP: Nodular granulomatous posthitis caused by Halicephalobus (syn. Micronema) sp. in a horse. Vet Pathol. 1993, 30: 207-208. 10.1177/030098589303000215.

Muller S, Grzybowski M, Sager H, Bornand V, Brehm W: A nodular granulomatous posthitis caused by Halicephalobus sp. in a horse. Vet Dermatol. 2007, 19: 44-48.

Bryant UK, Lyons ET, Bain FT, Hong CB:Halicephalobus gingivalis – associated meningoencephalitis in a Thoroughbred foal. J Vet Diagnos Invest. 2006, 18: 612-615. 10.1177/104063870601800618.

Nickels FA: Nasal passages and paranasal sinuses. Equine Surgery. Edited by: Auer JA, Stick JA. 2006, Saunders, Elsevier, Philadelphia, USA, 533-544. 10.1016/B1-41-600123-9/50044-9. 3

Eydal M, Bambir SH, Sigurdason S, Gunnarsson E, Svansson V, Fridriksson S, Benediktsson ET, Sigurdartóttir ÓG: Fatal infection in two Icelandic stallions caused by Halicephalobus gingivalis (Nematoda: Rhabditida). Vet Parasitol. 2012, 186: 523-527. 10.1016/j.vetpar.2011.11.024.

Pearce SG, Bouré LP, Taylor JA, Peregrine AS: Treatment of a granuloma caused by Halicephalobus gingivalis in a horse. J Am Vet Med Assoc. 2001, 219: 1735-1738. 10.2460/javma.2001.219.1735.

Ferguson R, van Dreumel T, Keystone JS, Manning A, Malatestinic A: Unsuccesful treatment of a horse with mandibular granulomatous osteomyelitis due to Halicephalobus gingivalis. Can Vet J. 2008, 49: 1099-1103.

Aleksandersen M, Gjerde B, Sørby R, Ropstad E, Teige J, Ihler CF, Thomassen R, Kjærstad HP, Brink P: Fire tilfelle av fatal infeksjon med nematoden Halicephalobus gingivalis (syn. H. deletrix) hos hest i Norge. Norsk Vettidsskr. 2000, 112: 7-14.

Christiansen JG, Oscarson M, Jensen HE, Jensen LK, Koch J, Aalbæk B, Nielsen OL, Iburg TM, Leifsson PS: Embolic encephalitis in a porcine model of endocarditis. In Vivo. 2013, 27: 591-598.

Kinde H, Mathews M, Ash L, Leger JS:Halicephalobus gingivalis (H. deletrix) infection in two horses in southern California. J Vet Diagn Invest. 2000, 12: 162-165. 10.1177/104063870001200213.

Lacombe VA, Sogaro-Robinson C, Reed SM: Diagnostic utility of computer tomography imaging in equine intracranial conditions. Eq Vet J. 2010, 42: 393-399. 10.1111/j.2042-3306.2010.00086.x.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Additional information

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interest.

Authors’ original submitted files for images

Below are the links to the authors’ original submitted files for images.

Rights and permissions

This article is published under an open access license. Please check the 'Copyright Information' section either on this page or in the PDF for details of this license and what re-use is permitted. If your intended use exceeds what is permitted by the license or if you are unable to locate the licence and re-use information, please contact the Rights and Permissions team.

About this article

Cite this article

Henneke, C., Jespersen, A., Jacobsen, S. et al. The distribution pattern of Halicephalobus gingivalis in a horse is suggestive of a haematogenous spread of the nematode. Acta Vet Scand 56, 56 (2014). https://doi.org/10.1186/s13028-014-0056-0

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/s13028-014-0056-0