Abstract

Background

The autosomal recessive disorder N-acetylglutamate synthase (NAGS) deficiency is the rarest defect of the urea cycle, with an incidence of less than one in 2,000,000 live births. Hyperammonemic crises can be avoided in individuals with NAGS deficiency by the administration of carbamylglutamate (also known as carglumic acid), which activates carbamoyl phosphatase synthetase 1 (CPS1). The aim of this case series was to introduce additional cases of NAGS deficiency to the literature as well as to assess the role of nutrition management in conjunction with carbamylglutamate therapy across new and existing cases.

Methods

We conducted retrospective chart reviews of seven cases of NAGS deficiency in the US and Canada, focusing on presentation, diagnosis, medication management, nutrition management, and outcomes.

Results

Five new and two previously published cases were included. Presenting symptoms were consistent with previous reports. Diagnostic confirmation via molecular testing varied in protocol across cases, with consecutive single gene tests leading to long delays in diagnosis in some cases. All patients responded well to carbamylglutamate therapy, as indicated by normalization of plasma ammonia and citrulline, as well as urine orotic acid in patients with abnormal levels at baseline. Although protein restriction was not prescribed in any cases after carbamylglutamate initiation, two patients continued to self-restrict protein intake. One patient experienced two episodes of hyperammonemia that resulted in poor long-term outcomes. Both episodes occurred after a disruption in access to carbamylglutamate, once due to insurance prior authorization requirements and language barriers and once due to seizure activity limiting the family’s ability to administer carbamylglutamate.

Conclusions

Follow-up of patients with NAGS deficiency should include plans for illness and for disruption of carbamylglutamate access, including nutrition management strategies such as protein restriction. Carbamylglutamate can help patients with NAGS deficiency to liberalize their diets, but the maximum safe level of protein intake to prevent hyperammonemia is not yet known. Patients using this medication should still monitor their diet closely and be prepared for any disruptions in medication access, which might require immediate dietary adjustments or medical intervention to prevent hyperammonemia.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Detoxification of ammonia occurs via the urea cycle and is dependent on the function of six enzymes and two mitochondrial transporters. Deficiency in one of these enzymes, N-acetylglutamate synthase (NAGS), inherited as an autosomal recessive disorder (17q21.31), is the rarest defect of the urea cycle, with an incidence of less than one in 2,000,000 live births [1]. NAGS is a mitochondrial enzyme that catalyzes the formation of N-acetylglutamate (NAG) [2], an essential activator of carbamoyl phosphate synthetase 1 (CPS1), the first enzyme of the urea cycle in mammals [3, 4]. Thus, NAGS deficiency results in dysregulation of ammonia detoxification [5, 6], which can lead to an array of symptoms with variable severity based on mutation status [7], including encephalopathy, coma, and death. Given the rarity of the disorder, it is unusual to have information on multiple cases, though several case reports have been published describing individual patient experiences [8].

The majority of patients with NAGS deficiency are diagnosed in infancy. In a review of 98 published cases of NAGS deficiency, 58% presented before the age of one month [8]. Presentation directly after birth includes poor feeding or feeding intolerance, vomiting, lethargy, hypertonia and/or hypotonia, seizures, and tachypnea. Common presenting symptoms in later onset cases include vomiting, confusion or disorientation, ataxia, lethargy, decreased level of consciousness, seizures, hypotonia, and in some cases, avoidance of high-protein foods [8]. Because it is possible to present apparently normal ammonia detoxifying function with partial NAGS deficiency, some cases can be difficult to diagnose until a hyperammonemic crisis occurs [1].

Treatment of acute hyperammonemia generally includes the use of nitrogen scavengers such as benzoate and phenylacetate, as well as the administration of carbamylglutamate [9]. Also known as carglumic acid, carbamylglutamate is a synthetic form of NAG that activates the CPS1 enzyme [10]. Once ammonia levels are stabilized and NAGS deficiency is diagnosed, treatment focuses on avoiding a future crisis event. Historically, this was done via limiting protein intake and avoiding catabolic stress [11]. However, the addition of long-term carbamylglutamate use has proven effective in allowing a more liberalized protein intake [5, 12,13,14].

Diagnosing and treating NAGS deficiency has been complicated by the variety of driver mutations, with over 50 mutations reported, and their associated symptoms and disease severity [8, 15]. Currently, there is a lack of consolidated and up-to-date literature that comprehensively covers cases of NAGS deficiency, particularly in understanding the area of nutritional interventions. Therefore, published descriptions of patients with NAGS deficiency, including presentation, recurring symptoms, and treatment, is essential to better understanding this condition. In this case series, we consolidate clinical information among seven treated patients with NAGS deficiency to provide insight into diagnosis and treatment, with a focus on medication and nutrition management, to contribute to the data supporting best practices.

Methods

This case series includes seven cases of NAGS deficiency treated in the United States (US) and Canada. Cases were identified by querying members of the Emory University Genetic Nutrition Online Metabolic listserv, which includes all Genetic Metabolic Dietitians International group members, as well as other practitioners who treat patients with inherited metabolic disorders (IMDs) or who have an interest in the nutrition management of patients with IMDs. We initiated discussions with an in-person meeting of registered dietitians who reported that they had managed a patient with NAGS deficiency. The meeting consisted of a didactic session followed by case presentations and group discussions. At this meeting and during subsequent follow-up telephone conferences, we developed a standardized data collection form to record retrospective information from medical records on clinical presentation, diagnostic procedures, medical interventions (including carbamylglutamate, citrulline, and arginine doses), nutrition interventions, and results of biochemical tests at various stages during diagnosis and treatment.

Data were collected and pooled using the online REDCap database housed at Emory University. REDCap is a secure, HIPAA-compliant, web-based application designed to support data capture for research studies, providing: (1) an intuitive interface for validated data entry; (2) audit trails for tracking data manipulation and export procedures; (3) automated export procedures for seamless data downloads to common statistical packages; and (4) procedures for importing data from external sources [16].

Human research ethics boards at all involved institutions either approved the data collection and sharing protocol or deemed it exempt from review.

Reference ranges for abnormal values are provided in the results section, as the ranges varied between institutions.

Results

Case reports

We present findings from medical chart review of seven patients with NAGS deficiency, including two previously reported cases: case 3 [17] and case 6 [13]. Relevant family history was reported in three cases: consanguinity (case 2), a younger sibling who was diagnosed four years prior to proband’s diagnosis (case 5), and a cousin with seizures (case 6). In the other four cases, family history was negative for consanguinity, as well as for relevant presentations such as NAGS deficiency, hyperammonemia, and infant death. Suspected triggers for presenting episodes of hyperammonemia included: a vomiting illness that progressed to respiratory symptoms and lethargy (case 4), menstruation (case 5), and influenza B (case 6). There was no suspected trigger in the other four cases. Presenting symptoms and relevant abnormal laboratory findings are included in Table 1. Plasma glutamine concentration was elevated in all cases at presentation. Plasma citrulline concentration at presentation was in the normal range for three cases, elevated in one case, and only borderline decreased in two cases. Of note, mildly elevated urine orotic acid concentrations were found in three cases.

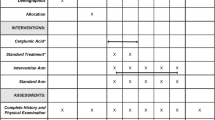

Initial treatments to reduce ammonia concentration are described in Table 1. Nutrition management was initiated prior to diagnosis of NAGS deficiency to reduce the risk of hyperammonemia (Table 2). Because diagnosis was a long process for many of the cases, management consisted of long-term protein restriction and medical management of episodes of hyperammonemia.

Molecular diagnoses (Table 3) led to the initiation of carbamylglutamate in all seven cases. Between the presenting episode and initiation of carbamylglutamate, six patients had at least one additional episode of hyperammonemia (Table 3). The exception was case 1, who was hospitalized at day 3 with medical management of ammonia levels until carbamylglutamate was initiated after results of genetic testing.

After initiation of carbamylglutamate, only one case had additional documented episodes of hyperammonemia (case 1). This occurred at ages 7 and 12 months and was associated with interrupted access to carbamylglutamate. The first interruption was due to an insurance prior authorization and language barrier and the second interruption occurred when the child experienced increased seizures and sleepiness and the family was unable to administer carbamylglutamate. At the time of first admission to the Emergency Department, the patient’s ammonia concentration was 278 µmol/L, and the hyperammonemia resolved upon administration of carbamylglutamate. In the second instance, carbamylglutamate was initiated immediately on admission, prior to measurement of ammonia concentration. In addition, one patient (case 5) reported that she suspects episodes of mild elevations during periods of intercurrent illness.

The results of molecular testing, chronic medical management, and outcomes are presented in Table 3. Five cases liberalized dietary protein intake, while two continued to self-restrict protein intake. Citrulline supplementation was continued in one case. The lowest dose of carbamylglutamate given that was not associated with hyperammonemia was 43 mg/kg/day. After carbamylglutamate initiation, dietary changes were associated with weight loss and improved diabetes management in case 7.

Biomarkers

Ammonia concentrations during the course of diagnosis and treatment are shown in Table 4. As indicated, ammonia concentrations decreased with the use of ammonia scavengers, although in three cases, ammonia concentration did not reach the normal range until after initiation of carbamylglutamate.

Table 4 also includes concentrations for plasma glutamine, alanine, arginine, citrulline, and urine orotic acid. Treatment with carbamylglutamate resulted in normalization of these biomarkers. At the most recent measurement, all biomarkers were in the normal range, with the exception of case 4 for whom plasma glutamine was slightly below the normal range.

Discussion

As the rarest urea cycle defect, with no common mutation and with variable symptom presentation, diagnosis and management of NAGS deficiency may be challenging. A review of 34 NAGS deficiency case reports is available, but was released over one decade ago [18]. In addition, reports that have combined data of patients with urea cycle disorders (UCD) in Europe [19] and in Japan [20] have not included patients with NAGS deficiency. Our systematic collection of patient data provides a cohesive picture of NAGS deficiency and will assist clinicians in refining best practices for treatment, especially as it relates to medication and nutritional management. Dietitians during the initial meeting all communicated lack of knowledge and confidence about guiding protein liberalization to patients upon initiation of carbamylglutamate. This case series addresses a continued critical knowledge gap in the description of NAGS deficiency and treatment.

In their review of 34 published cases of NAGS deficiency, Ah Mew and Caldovic made several conclusions [18] that are validated by our case series. First, they reported that the lowest reported daily dose of carbamylglutamate required to prevent hyperammonemia was 15 mg/kg/day. According to the manufacturer, the recommended daily maintenance dose of carbamylglutamate for patients with NAGS deficiency is 10 mg/kg to 100 mg/kg divided into two to four doses [21]. In our patient cases, doses ranged from 43 to 100 mg/kg/day and most were divided into two or three doses per day. In two cases, the carbamylglutamate was mixed with food (applesauce or banana puree). Although mixing with food is not recommended by the manufacturer, as the impact on efficacy has not been studied [21], mixing with food was part of successful treatment adherence for two of the cases we report. Second, Ah Mew and Caldovic reported that carbamylglutamate allowed for protein intake of 2 to 3 g/kg/day in some infant patients, although one patient became mildly ataxic after ingestion of more than 3.5 g/kg/day [18]. We found similar results. Of our seven cases, five have no protein restriction and two self-restrict at 0.6 and 1.3 g/kg/day. There were no reports among our cases of adverse events associated with high protein intake, intercurrent illness, or inadequate caloric intake. However, there were limited dietary data in the charts as monitoring by dietitians was generally limited after initiation of carbamylglutamate.

Third, Ah Mew and Caldovic concluded that protein restriction during illness may be prudent if poor oral tolerance prevents the administration of carbamylglutamate [18]. Two of our cases had formalized plans for illness (one reduced protein and both increased carbamylglutamate dose), but no cases had an established plan for lack of access to carbamylglutamate. Finally, the 2011 review reported that timely administration of carbamylglutamate to affected neonates who presented with acute hyperammonemia resulted in normal psychomotor development [18]. Among our cases, three had poor long-term medical outcomes, which do not appear to be related to hyperammonemia in two of the cases, but was due to a lapse in access to carbamylglutamate in the third (case 1).

Patient management and outcomes among our seven cases add support to the current guidelines recommending carbamylglutamate with nutrition management for controlling ammonia concentrations for patients with NAGS deficiency. None of our cases required other ammonia scavengers such as sodium benzoate and phenylbutyrate after the initiation of carbamylglutamate. Likewise, six of the seven cases were able to discontinue arginine and citrulline supplements, although one continued to use citrulline supplements as part of disease management. Therefore, this report endorses the guidelines recommending carbamylglutamate as an effective and well-tolerated treatment option for individuals with NAGS deficiency.

While there were delays in initiation of carbamylglutamate in several of our cases until after diagnosis of NAGS deficiency, current guidelines recommend the administration of carbamylglutamate in all cases of unexplained hyperammonemia (> 100 µmol/L), with long-term continuation of carbamylglutamate if NAGS deficiency is confirmed [9]. This suggests that widespread dissemination of guidelines for the use of carbamylglutamate in cases of unexplained hyperammonemia is warranted.

Carbamylglutamate has also been used in the treatment of other disorders, most notably organic acidurias. In 2021, the US Food and Drug Administration approved carbamylglutamate for the treatment of acute hyperammonemia associated with propionic acidemia (PA) and methylmalonic acidemia (MMA) [22]. The mechanism for the effectiveness of carbamylglutamate in these conditions is still not clear. It has been proposed that accumulation of propionyl-CoA or methylmalonyl-CoA, respectively, causes competitive inhibition of NAGS [23], which may be compensated for by carbamylglutamate.

This case series includes three previously unreported mutations. There was no standardized approach to genetic testing for the cases in this report. A definitive diagnosis of NAGS deficiency, based on DNA, was a rate-limiting factor, often taking years, with single gene tests ordered sequentially. Gene panels for hyperammonemia or whole exome sequencing may address this issue, but may miss some mutations if regulatory regions are not included. Therefore, whole genome sequencing may be considered an efficient option. Additional data on the genetic diagnosis process, including turnaround times, will be important and may help to inform evidence-based guidelines on DNA testing for patients presenting with acute hyperammonemia. Current guidelines for urea cycle disorders include DNA testing for confirmation of NAGS deficiency, although the specific methodology for the genetic testing is not outlined [9].

Ah Mew and Caldovic describe the biochemical presentation of NAGS deficiency as including elevated plasma ammonia and glutamine concentrations, and low-to-normal concentrations of other urea cycle intermediates, while plasma citrulline is frequently low or undetectable [18]. Plasma glutamine was elevated in all of our cases at presentation, as expected. However, citrulline was normal at presentation in three of our cases, borderline in two, and high in one. In one case (case 1), citrulline was reduced from normal to zero after hemodialysis without citrulline supplementation and prior to initiation of carbamylglutamate. Furthermore, while it has been commonly accepted that NAGS deficiency presents with low or normal urine orotic acid prior to administration of carbamylglutamate [9], we report slightly elevated urine orotic acid concentration in three of the seven cases. Marginal to mild elevations have also been previously reported in three other patients with NAGS deficiency [15, 24]. The cause and any clinical consequence of this elevation remain to be understood, but our results indicate that mild elevations in urine orotic acid concentration should not be used to rule out NAGS deficiency.

Conclusions

In conclusion, we report on the diagnosis and management history of seven cases of NAGS deficiency in the US and Canada. By incorporating an in-person meeting with case presentations and discussion into our methodology, the providers learned from each other and identified topics for comprehensive chart review and data collection strategies. The biochemical profiles during presentation in some of our cases did not align with previously published NAGS deficiency cases, suggesting further case review and consensus is needed to fully characterize biomarkers suggestive of NAGS deficiency. Despite the availability and efficacy of carbamylglutamate for the treatment of NAGS deficiency, there remains heterogeneity in management approaches, with differences in protein intake and micronutrient supplementation. In addition to developing formalized plans for disease management during times of illness, which may include protein restriction and increased doses of carbamylglutamate, we also recommend that clinicians work with families to develop nutrition management plans for unexpected lapses in access to carbamylglutamate. In addition, while protein restriction is generally not needed when carbamylglutamate is used during chronic management, the upper limit of protein and caloric intake needs to be further assessed with ongoing dietary management to understand the potential impact of higher levels of protein intake. NAGS deficiency is the only urea cycle disorder which can be specifically and effectively treated with medication, with the potential of having an unrestricted diet. Early and continuous treatment with carbamylglutamate optimizes outcome. However, there remains a need for further dissemination of and education related to the guidelines for the use of carbamylglutamate during unexplained hyperammonemia.

Data availability

The datasets generated and analyzed during the current study are not publicly available because they were created under data sharing agreements between the partnering institutions which preclude the sharing of data to additional parties. Data are however available from the authors upon reasonable request and with permission of individual institutions.

Abbreviations

- ALT:

-

Alanine transaminase

- AST:

-

Aspartate aminotransferase

- BUN:

-

Blood urea nitrogen

- CPS1:

-

Carbamoyl phosphatase synthetase 1

- CVVH:

-

Continuous veno-venous hemofiltration

- FDA:

-

Food and Drug Administration

- HIPAA:

-

Health Insurance Portability and Accountability Act

- IMD:

-

Inherited metabolic disorder

- IV:

-

Intravenous

- MMA:

-

Methylmalonic acidemia

- NAG:

-

N-acetylglutamate

- NAGS:

-

N-acetylglutamate synthase

- PA:

-

propionic acidemia

- TPN:

-

Total parenteral nutrition

- TSH:

-

Thyroid stimulating hormone

- US :

-

United States

References

Summar ML, Koelker S, Freedenberg D, Le Mons C, Haberle J, Lee HS, et al. The incidence of urea cycle disorders. Mol Genet Metab. 2013;110(1–2):179–80.

Shigesada K, Tatibana M. Enzymatic synthesis of acetylglutamate by mammalian liver preparations and its stimulation by arginine. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 1971;44(5):1117–24.

Hall LM, Metzenberg RL, Cohen PP. Isolation and characterization of a naturally occurring cofactor of carbamyl phosphate biosynthesis. J Biol Chem. 1958;230(2):1013–21.

Rubio V, Ramponi G, Grisolia S. Carbamoyl phosphate synthetase I of huma liver. Purification, some properties and immunological cross-reactivity with the rat liver enzyme. Biochim Biophys Acta. 1981;659(1):150–60.

Caldovic L, Morizono H, Daikhin Y, Nissim I, McCarter RJ, Yudkoff M, Tuchman M. Restoration of ureagenesis in N-acetylglutamate synthase deficiency by N-carbamylglutamate. J Pediatr. 2004;145(4):552–4.

Tuchman M, Caldovic L, Daikhin Y, Horyn O, Nissim I, Nissim I, et al. N-carbamylglutamate markedly enhances Ureagenesis in N-acetylglutamate Deficiency and Propionic Acidemia as measured by isotopic incorporation and blood biomarkers. Pediatr Res. 2008;64(2):213–7.

Sancho-Vaello E, Marco-Marin C, Gougeard N, Fernandez-Murga L, Rufenacht V, Mustedanagic M, et al. Understanding N-Acetyl-L-Glutamate Synthase Deficiency: mutational spectrum, impact of clinical mutations on enzyme functionality, and structural considerations. Hum Mutat. 2016;37(7):679–94.

Kenneson A, Singh RH. Presentation and management of N-Acetylglutamate Synthase Deficiency: a review of the literature. Orphanet J Rare Dis. 2020;15(1):279.

Häberle J, Burlina A, Chakrapani A, Dixon M, Karall D, Lindner M, Mandel H, Martinelli D, et al. Suggested guidelines for the diagnosis and management of urea cycle disorders: first revision. J Inherit Metab Dis. 2019;42(6):1192–230.

Grisolia S, Cohen PP. The catalytic role of carbamyl glutamate in citrulline biosynthesis. J Bio Chem. 1952;198(2):561–71.

Walker V. Ammonia toxicity and its prevention in inherited defects of the urea cycle. Diabetes Obes Metab. 2009;11(9):823–35.

Gessler P, Buchal P, Schwenk HU, Wermuth B. Favourable long-term outcome after immediate treatment of neonatal hyperammonemia due to N-acetylglutamate synthase deficiency. Eur J Pediat. 2010;169(2):197–9.

Heibel SK, Ah Mew N, Caldovic L, Daikhin Y, Yudkoff M, Tuchman M. N-carbamylglutamate enhancement of ureagenesis leads to discovery of a novel deleterious mutation in a newly defined enhancer of the NAGS gene and to effective therapy. Hum Mutat. 2011;32(10):1153–60.

Kim JH, Kim YM, Lee BH, Cho JH, Kim GH, Choi JH, Yoo HW. Short-term efficacy of N-carbamylglutamate in a patient with N-acetylglutamate synthase deficiency. J Hum Genet. 2015;60(7):395–7.

Häberle J, Moore MB, Haskins N, Rüfenacht V, Rokicki D, Rubio-Gozalbo E, Tuchman M, et al. Noncoding sequence variants define a novel regulatory element in the first intron of the N-acetylglutamate synthase gene. Hum Mutat. 2021;42(12):1624–36.

Harris PA, Taylor R, Thielke R, Payne J, Gonzalez N, Conde JG. Research electronic data capture (REDCap)--a metadata-driven methodology and workflow process for providing translational research informatics support. J Biomed Inf. 2009;42(2):377–81.

Cartagena A, Prasad AN, Rupar CA, Strong M, Tuchman M, Ah Mew N, Prasad C. Recurrent encephalopathy: NAGS (N-acetylglutamate synthase) deficiency in adults. Can J Neurol Sci. 2013;40(1):3–9.

Ah Mew N, Caldovic L. N-acetylglutamate synthase deficiency: an insight into the genetics, epidemiology, pathophysiology, and treatment. Appl Clin Genet. 2011;4:127–35.

Adam S, Almeida MF, Assoun M, Baruteau J, Bernabei SM, Bigot S, Champion H, et al. Dietary management of urea cycle disorders: European practice. Mol Genet Metab. 2013;110(4):439–45.

Kido J, Matsumoto S, Häberle J, Nakajima Y, Wada Y, Mochizuki N, Murayama K, et al. Long-term outcome of urea cycle disorders: report from a nationwide study in Japan. J Inherit Metab Dis. 2021;44(4):826–37.

Recordati Rare Diseases. (2021) US Prescribing Information. https://www.recordatirarediseases.com/files/inline-files/carbaglu-pi-122019.pdf. Accessed 01 July 2022.

Recordati Rare Diseases. (2021) CARBAGLU® (Carglumic Acid) Tablets 200 mg Receives U.S. FDA Approval for a New Indication to Treat Acute Hyperammonemia Associated with Propionic Acidemia and Methylmalonic Acidemia. https://www.recordatirarediseases.com/us/node/218. Accessed 18 January 2024.

Alfadhel M, Nashabat M, Saleh M, Elamin M, Alfares A, Al Othaim A, Umair M, et al. Long-term effectiveness of carglumic acid in patients with propionic acidemia (PA) and methylmalonic acidemia (MMA): a randomized clinical trial. Orphanet J Rare Dis. 2021;16(1):422.

Selvanathan A, Demetriou K, Lynch M, Lipke M, Bursle C, Elliott A, et al. N-acetylglutamate synthase deficiency with associated 3-methylglutaconic aciduria: a case report. JIMD Rep. 2022;63(5):420–4.

Acknowledgements

Not applicable.

Funding

This project was funded by an educational grant from Recordati Rare Diseases.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Conceptualization: RHS. Funding acquisition: RHS. Methodology: All authors. Data curation: RHS, MHB, AKu EM, CN, SR, SCVC. Analysis: AKe. Project administration: RHS, AKe. Writing– original draft: AKe. Writing– reviewing and editing: All authors.RHS: Rani H. Singh, PhD, RD, LD, Emory University School of Medicine, Atlanta, GA, USA.MHB: Marie-Hélène Bourdages, RD, Children’s University Hospital of Quebec, Quebec, Canada.AKu: Angela Kurtz, RD, Mount Sinai, New York, NY, USA.EM: Erin MacLoed, PhD, RD, LD, Children’s National Medical Center, Washington, DC, USA.CN: Chelsea Norman, RD, University of Utah, Salt Lake City, UT, USA.SR: Suzanne Ratko, RD, London Health Sciences Centre, London, Ontario, Canada.SCVC: Sandra C. van Calcar, PhD, RD, LD, Oregon Health & Science University, Portland, OR, USAAKe: Aileen Kenneson, PhD, MS, Emory University School of Medicine, Atlanta, GA, USA.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate

The Human Research Ethics Boards of the following institutions reviewed the protocol and either approved it or deemed it exempt from review: Emory University School of Medicine, Children’s University Hospital of Quebec, Mount Sinai, Children’s National Medical Center, University of Utah, London Health Sciences Centre, and Oregon Health & Science University. Each institution waived the requirement for informed consent.

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/. The Creative Commons Public Domain Dedication waiver (http://creativecommons.org/publicdomain/zero/1.0/) applies to the data made available in this article, unless otherwise stated in a credit line to the data.

About this article

Cite this article

Singh, R.H., Bourdages, MH., Kurtz, A. et al. The efficacy of Carbamylglutamate impacts the nutritional management of patients with N-Acetylglutamate synthase deficiency. Orphanet J Rare Dis 19, 168 (2024). https://doi.org/10.1186/s13023-024-03167-0

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/s13023-024-03167-0