Abstract

Background

The diversity of patient experiences of orphan drug development has until recently been overlooked, with the existing literature reporting the experience of some patients and not others. The current evidence base (the best available current research) is dominated by quantitative surveys and patient reported outcome measures defined by researchers. Where research that uses qualitative methods of data collection and analysis has been conducted, patient experiences have been studied using content analysis and automatic textual analysis, rather than in-depth qualitative analytical methods. Systematic reviews of patient engagement in orphan drug development have also excluded qualitative studies. The aim of this paper is to review qualitative literature about how patients and other members of the public engage with orphan drug development.

Methods

We conducted a systematic search of qualitative papers describing a range of patient engagement practices and experiences were identified and screened. Included papers were appraised using a validated tool (CASP), supplemented by reporting guidance (COREQ), by two independent researchers.

Results

262 papers were identified. Thirteen papers reported a range of methods of qualitative data collection. Many conflated patient and public involvement and engagement (PPIE) with qualitative research. Patients were typically recruited via their physician or patient organisations. We identified an absence of overarching philosophical or methodological frameworks, limited details of informed consent processes, and an absence of recognisable methods of data analysis. Our narrative synthesis suggests that patients and caregivers need to be involved in all aspects of trial design, including the selection of clinical endpoints that capture a wider range of outcomes, the identification of means to widen access to trial participation, the development of patient facing materials to optimise their decision making, and patients included in the dissemination of trial results.

Conclusions

This narrative qualitative synthesis identified the explicit need for methodological rigour in research with patients with rare diseases (e.g. appropriate and innovative use of qualitative methods or PPIE, rather than their conflation); strenuous efforts to capture the perspectives of under-served, under-researched or seldom listened to communities with experience of rare diseases (e.g. creative recruitment and wider adoption of post-colonial practices); and a re-alignment of the research agenda (e.g. the use of co-design to enable patients to set the agenda, rather than respond to what they are being offered).

Similar content being viewed by others

Explore related subjects

Find the latest articles, discoveries, and news in related topics.Background

Orphan diseases are often so rare that physicians have little knowledge of these conditions, while the contribution of patients to orphan drug development is under-documented [1]. Recent changes in the policy and regulatory landscape have enshrined the contribution of patients and patient organisations into the drug development lifecycle. On the 31st January 2022, the Clinical Trials Directive (EC) No. 2001/20/EC was repealed [2], and a transition period (until 2023) entered under Clinical Trials Regulation (Regulation (EU) No 536/2014) [3]. The objective of the new Clinical Trials Regulation is to harmonise the processes for assessment and supervision of clinical trials throughout the European Union (EU). The directive stipulates a greater role for patients and patient organisations (defined by the European Medicines Agency as not-for profit organisations which are patient focused, and whereby patients and/or carers -the latter when patients are unable to represent themselves- represent a majority of members in governing bodies) in the oversight of, and access to, clinical trials. In the UK, the Rare Disease Framework similarly outlined ambitions to improve patient access to new therapeutics, premised on a commitment to consultation with patient representatives, and explicitly those from Black, Asian and minority ethnic (BAME) or disadvantaged backgrounds [4].

Existing research suggests that the diversity of patient experiences of orphan drug trials has been overlooked [5, 6]. The current evidence base is dominated by surveys of patients who have had a positive experience of trial participation or treatment, practitioners who provide these treatments, or surveys of patient and public representatives interested in drug trial development [7, 8]. Where qualitative evidence of patient experiences have been collected, they have been subject to content analysis and automatic textual analysis [9, 10], rather than in-depth qualitative analyses that could inform improvement. There is a gap in knowledge around the experience of patients who have limited access to clinical trials of genomic treatments, and those who do not receive the active treatment, who withdraw from the trial, or for whom there is a perception that the drug is ineffective [11].

Recently, Brown and Bahri have proposed a conceptual and methodological framework for evaluating patient and public engagement in relation to pharmacovigilance, which delineated engagement in terms of three dimensions [12]:

-

Breadth: the diversity of patient engagement;

-

Depth: The extent of knowledge exchange between stakeholders; and

-

Texture: The interactive dynamics of what engagement feels like, means to people, and shapes their motivations to engage and change behaviour-based on values, emotions, (mis)trusts, and rationales.

Furthermore, they note that qualitative research is particularly suited to evaluating both the perspectives and mechanisms of engagement activities. Noting a rise in the volume of quantitative research that purports to concern patient and public engagement in the orphan drug development lifecycle [13, 14], we employed Brown and Bahri’s framework to establish the extent to which corresponding qualitative research could deepen our understanding of current engagement practices [12].

The aim of this paper is to explore how patients and other members of the public engage with the process of orphan drug development.

Methods

Patient advisory group

A Patient Advisory Group (PAG) were convened prior to the funding application, and met regularly to discuss the scope and content of the research. The group consisted of 6 local members of a rare disease group, and 2 members of a national group. The scope and content of the review were also discussed with the Steering Group, which also includes a patient from an international patient organisation. The PAG did not want to be cited as authors [13] but we acknowledge their contribution to this review.

Literature search

Orphan drug terminology is highly specialised, and we started our search by gathering a selection of papers using search methods that do not rely on keyword terminology. This was informed by the work of Zhao [14], who outlines the role of ‘meta-’ in the synthetic process, and the need to identify the ‘state of play’ of a given area of study. We followed Zhao’s advice to use qualitative synthesis as diagnostic. For Zhao: “[synthesis] starts with an examination of problems encountered in primary study and ends with prescriptions for resolving these” (14: 381).

To this end, we conducted forward citation searches of two topically relevant systematic reviews using Google Scholar (https://scholar.google.com/), which although had excluded qualitative papers during searching and screening exposed us to topically relevant literature [15, 16]. The lead author (JF) knew the systematic reviews from background reading. We also inspected the studies included in these reviews. Qualitative primary studies which met our inclusion criteria, and which could inform the development of the bibliographic database search strategy, were examined for keyword terminology. We also examined quantitative primary studies for topic related terminology, even though these would not be included within the analysis.

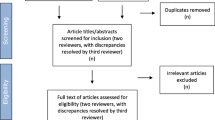

The bibliographic database search strategy was developed by an information specialist in conjunction with the review team. The search strategy was developed in MEDLINE (via Ovid)). Search terms for orphan drugs and rare diseases were derived from the titles, abstracts and indexing terms (e.g. MeSH in MEDLINE) of pre-identified relevant studies and supplemented with appropriate synonyms. As a corrective to previous reviews, which had excluded qualitative papers, we combined these terms with two published search filters: a patient and public involvement search filter [17] and a qualitative search filter [18]. However this yielded a prohibitive number to screen in full (n = 6935), as many of the studies were irrelevant (e.g. beyond our area and scope of interest, Fig. 1: Initial search). We therefore focused the search by limiting the results to articles which were indexed with any of four highly discriminating methodological MeSH terms: qualitative research, interviews, focus groups, and patient participation. This retrieved a more focused sample (n = 262; Fig. 2: Amended search).. Our intention was not to conduct an exhaustive survey of the field, but to establish the extent to which qualitative research could deepen our understanding of current engagement practices. To do this does not require a review of all papers for all rare diseases, but instead draws on established qualitative sampling approaches, seeking ‘information power’; which depends on (a) the aim of the study, (b) sample specificity, (c) use of established theory, (d) quality of dialogue, and (e) analysis strategy [19]. As we wanted to sample a selection of relevant studies rather than search exhaustively, we limited the search to the MEDLINE database and the results of forward citation searching. The results of both the forward citation searches and the MEDLINE search were exported to Endnote X8 [20] and de-duplicated using both the automated de-duplication function and manual checking. The bibliographic database search was conducted on 11th June 2021.

Quality appraisal

Two researchers (AH, ET), independently applied the Critical Appraisal Skills Programme (CASP) checklist to assess the quality of the studies selected for inclusion [21] (Table 1). Quality appraisal is contentious in qualitative syntheses, because there is limited consensus about what makes a study good [22,23,24]. To further understand the context in which the research was conducted, we also used a validated 32-item checklist to provide a means to assess the rigour and validity of the data collection and analysis techniques used by the research authors [25].

Synthesis method

The purpose of qualitative synthesis is to achieve greater understanding and attain a level of conceptual or theoretical development beyond that achieved in any individual empirical study [26]. We had planned to undertake a meta-ethnography [27], to identify where similar concepts and themes from different studies or papers refer to the same entity or to opposing findings, with the objective of moving current debates about patient engagement forward [14]. However, as the included papers identified were not deemed to be ‘conceptually rich’ in that they did not extend our understanding [28, 29]. A paper is considered to be conceptually rich in qualitative synthesis if it makes a substantial contribution to the synthesis. In this context, critical appraisal is not undertaken to exclude papers prior to the synthesis, but to ‘test’ the contributions of the papers at a later stage [30]. We therefore undertook a narrative synthesis, appropriate when a wide range of research designs are included, and to tell the story of existing data [31]. The lead author (JF) tabulated data from the included papers using a standardised data extraction table, which enabled the derivation of themes that mapped onto the lifecycle of orphan drug development [32], and these were discussed and refined by the wider research team.

Results

Of the 262 abstracts identified, we excluded 192 that were explicitly quantitative (e.g. surveys, or concerning the development of patient reported outcome measures), or not about drug development (e.g. genetic sequencing and diagnostic pathways). Of the 70 full-text papers that we reviewed (Fig. 3: Identification of studies, and Additional file 1: Full texts retrieved), we excluded 57 papers that did not contain primary qualitative data (e.g. literature reviews, research protocols, opinion pieces, letters, editorials and organisations statements); were not deemed to be methodologically robust (e.g. they did not have sufficient information concerning recruitment, data collection or analysis to be replicable); or which were substantively not significant (e.g. they reported on focus groups or workshops, but the perspectives of rare disease patients, caregivers, representatives of patient organisations, or members of the public were missing, or could not be disaggregated from a wider ‘stakeholder voice’ that included health professionals or policy makers).

Identification of studies. Adapted from: Page MJ, McKenzie JE, Bossuyt PM, Boutron I, Hoffmann TC, Mulrow CD, et al. The PRISMA 2020 statement: an updated guideline for reporting systematic reviews. BMJ 2021;372:n71. https://doi.org/10.1136/bmj.n71. For more information, visit: http://www.prisma-statement.org/

Study characteristics

We included 13 published papers from a 10 year period (2012–2022)—with studies originating from the USA (5) [33,34,35,36,37], Canada (4) [38,39,40,41], Europe (2) [42, 43], Brazil (1) [44] and China (1) [45], and which detailed 11 separate studies (e.g. both papers by Gaasterland et al. [42, 43] and both papers by Tingley et al. [39, 40] pertained to the same data sources) (Table 2). Three papers recruited the parents of children with rare diseases who considered trials as a means to access treatment [33, 34, 36]; while two papers included representatives of patient organisations concerned by the lack of access to research in specific countries [44, 45]. The included papers formed a dataset spanning key junctures of the orphan drug development lifecycle.

Papers included patient and public involvement and engagement (PPIE) activities with patient representatives from umbrella patient organisations, as well as qualitative research with individual patients or caregivers from single disease organisations or attending clinics; but sometimes the boundaries between PPIE and research were blurred (e.g. stakeholder activities without research ethics approval presented as ‘data’). Most papers included identifiable approaches to qualitative data collection [36, 37]; however, counter to reporting guidance for qualitative research [25], only one paper [35] included an overarching methodological framework, with some citing reporting guidance, rather than qualitative methodological literature, as informing their research design [43]. Few papers provided details of how the authors conducted their qualitative analyses, although some reported findings statistically [33]. Some papers were more akin to reports of patient and public involvement/engagement (PPIE) workshops, or stakeholder events with mixed patient and clinician populations [44]. Few papers detailed the relationship between the author and participants, with limited reflexivity about their role in the construction of the research findings [21, 25]; thus making it difficult to discern how patients and other members of the public contributed to the generation of substantive knowledge about patient engagement in orphan drug development.

The 4 substantive headings, below, were those most used by the authors of the papers under review (as sub-headings) in their interpretations of the stakeholder perspectives in the primary papers, and typically follow the chronological processes of clinical trial and drug development [46, 47].

Trial design

Earlier research identified that patients with rare diseases want to see the adoption of a faster approval processes of new therapeutic agents that would produce effective treatments and improve their quality of life [36]. More recently, attention has turned to how patients, as experts in their own disease, can be active agents in the development of trial protocols, rather than merely as trial recipients [38, 41, 43]:

‘‘Because we’re talking about all the problems that happen after clinical trials are designed by people who know the science and the industry, but don’t know the disease and that’s the problem. We’re dealing with the problems because we’re not included before the trial begins.’’ (Participant, Menon et al 2015: 108).

Patient representatives reported negative perceptions of conventional randomised control trial designs and placebo controlled studies [39]. Instead, they suggested that their involvement in the trial design and protocol development could mitigate burdensome treatment regimens [41], and widen the parameters of enrolment to ensure that findings had increased external validity and thus applicability to a wider patient population [39].

Several papers suggested that patients and caregivers are not prepared to accept the outcome measures and clinical endpoints which trial designers’ currently offer [35, 39], and which fail to adequately account for quality of life [36]. The ‘true value’ of a therapy can therefore be lost because current outcome measures focus on what is easy to measure [38], or use standardised measures, rather than focusing on outcomes of interest to specific populations [39]. Authors also described the difficulty in eliciting patient outcomes and the need for new models of outcome development [42]:

“We [authors] decided that the best results would be achieved when researchers translate the patient’s preferences in outcomes, which are formulated in the first meeting, into measurement instruments and a trial protocol which can then be evaluated again with patient representatives during the second meeting.” (Gaasterland et al 2018: 1290)

The selection of clinical endpoints that were not considered as meaningful to reimbursement decision-makers was also a cause of frustration [41], and patient representatives identified that they should have a greater role in both research and reimbursement funding priorities [38].

Trial access

Patient representatives expressed disappointment when inclusion criteria, such as the phase of a disease, co-morbidities and existing medication regimens inhibit enrolment [33, 36]. Clinicians were viewed as gatekeepers, who can limit the enrolment of patients from minority backgrounds, due to beliefs that they will be unable to fulfil the research objectives or be non-compliant [33]. Lack of sponsorship can ensure that patients require sufficient ‘cultural health capital’, in order to push for access to a clinical trial [35]:

“Todd recalled the diagnosing physician telling them, “Go look for clinical trials—‘you go do your homework and I’ll do mine.’” But at their next visit, Savannah reported, “He hadn’t done anything. Like . . . he had printed out another sheet from his database . . . and told us, ‘Oh, looks like he has 2–4 years to live.’” Unwilling to accept this outcome, the Marins “did their homework” and scoured FDA databases for clinical trials.” (Gengler 2014: 346)

Several papers described the burden on patients of travelling to and from study appointments [34], which was magnified when parents of disabled children were required to stay in unfamiliar places without support networks [33]. Proposed solutions included financial remuneration, but also flexibility [34]:

“I might consider doing it depending on the leniency of when I could come in or what hours can I come into the office. I would be more drawn to a study that brought me in fewer times a week” (Participant, Carroll et al 2012:7)

A key motivator for trial participation was disease progression and associated high expectations for the benefit of trial medicines [37], even when patients themselves were unlikely to derive individual benefit [40]. In countries, yet to establish registries and normalise trial delivery, wider financial incentives were called for [44, 45].

Trial participation

While patient registries were seen as an important tool for monitoring rare diseases, and a means to recruit sufficient participants to a trial [38, 45], there were also concerns that they are only ‘suitable for highly motivated or informed volunteers who are specifically interested in research’ [33].

Despite the lack of a strong evidence base, rare disease patients are often willing to participate in trials of new drugs, even when they perceive that improvement may be minimal [36, 41]:

“There isn’t enough available for you to be able to prioritize, and so therefore you will grasp at anything that is acceptable to you. It doesn’t matter if it’s going to perhaps improve by 1% or by 50% or will get to the cure level of 100%. You will take it.” (Advocate, Kessselheim et al 2014: 78)

Throughout the drug lifecycle, decisions around what constitutes acceptable harm in order to achieve a certain magnitude of benefit are traditionally made with minimal input from patients, suggesting that there is significant scope for patients and families to be engaged as equal partners in such decisions [38]. Patients have suggested that they are concerned about the side effects of experimental medicines, and the consequences of stopping current drug regimens [34]; while others have expressed fears about making the ‘wrong’ decision, in agreeing to participate in a trial or not [41]. This can be compounded when patients are assigned to a control arm in a trial, and when the perception of any ‘potential gain’ is diminished [36]. Other patients have suggested that they have only been able to weigh up risks and harms retrospectively, that is after a trial, and specifically when any perceived improvement is subsequently lost [33].

Significant attention has also been given to the potential role of patient representatives in the design of patient-facing information. Patients and their caregivers often perceive that there is an over-abundance of information, which is fragmented, difficult to obtain, or difficult to understand [33] and which, paradoxically, can obfuscate that trials are performed in hospital with the objective of generating evidence about the effectiveness of treatments [43]. In the one example, where a trial was terminated before completion, parents reported feeling powerless, as their sense of hope receded [38]:

When he called up and said stop taking the medicine, I felt that conversation was worse than the diagnosis phone call when they told me he had muscular dystrophy... hope goes a long way, and to take that from a family is just pretty devastating ... The shattering part was because it was his cure. (Father 107, Peay et al 2014: 82)

In this example, parents were not prepared for a common trial outcome (no effect on the primary trial endpoint), which was compounded by the desperation wrought by the lack of available treatment (often typical for the rare disease community), and exacerbated by perceptions that the trial drug was of benefit for their children (in the absence of alternatives). It is suggested that patient facing information needs to better prepare participants for the possibility of a trial ending abruptly [38]; and patients have suggested that peer support and the use of social media could be used provide patient-to-patient information and support [33, 40, 42]

Dissemination

Two recent papers acknowledge that patient engagement activities typically end when their participation in a clinical trial finishes [40, 43]. Participants suggest that the results of a study need to be communicated to patients, both more often and more clearly [40, 41]:

“…I think that’s a really important piece to keep people motivated to participate in these things is to at least have some sort of follow through that allows us to see if what we shared made any kind of a difference. So that would be one thing that I’d like to see…”(Patient/caregiver 4, Tingley et al 2021: 6).

This would enable patients to evaluate their contribution to the research, as well as potentially encourage future participation in research [40].

Discussion

By formally appraising qualitative studies about how members of the public engage with orphan drug development, and employing the framework developed by Brown and Bahri [12], we identified a lack of depth in existing studies, due to the lack of understanding and rigorous application of methodologically informed qualitative research [48, 49]. Limitations include: the conflation of patient and public involvement and engagement (PPIE) and qualitative research, and a lack of detail pertaining to recognised qualitative analysis techniques (e.g. thematic or narrative analysis), and limited reflexivity about the authors relationship to those being researched [21, 26]. We also identified the adoption of a range of more quantitative techniques within papers purporting to have used qualitative methods. These include: interviews no longer than 10 min in length [34], the use of closed questions [44], and statistical analyses [33], which inhibited the development of richer understandings of patients’ unmet needs.

Recent research undertaken by EURODIS has identified that a barrier to sustaining meaningful patient engagement in rare disease research is a lack of knowledge on how to apply methodologies to capture and use patient insights [50]. More specifically, du Plessis et al. [51] have identified a lack of understanding of, and respect for, qualitative research methods that often form the foundation of patient-centric research in drug development. This lack of methodological knowledge matters, when engagement is becoming the new standard for patient-facing clinical trials and the development of new medicines to address patient needs [52].

Our analysis identified that patients and caregivers need to be involved in study design (including protocol development and the selection of measures that capture a range of outcomes, e.g. quality of life, beyond clinical endpoints) to optimise recruitment and demonstrate effectiveness. Patients and caregiver input is also necessary to ensure that trial providers enable access to the trial, develop patient facing materials that facilitate meaningful decision making, and disseminate results to patients to acknowledge their contribution and foster future collaboration. That these findings align with critical junctures for patient engagement identified in existent roadmaps for the drug development pipeline, developed by rare disease patient organisations is unsurprising [50, 52].

Earlier research about patient organisations generally, and those for rare diseases specifically, identified their imperative to engage with, and sometimes dependence upon, both the agenda and financial sponsorship of pharmaceutical organisations [53,54,55]. However, the roadmap developers are clear that these plans remain aspirational, rather than realised; with examples in the wider literature of sub-optimal patient engagement, in terms of lack of opportunities for genuine involvement in decision making [56], and acknowledgment that the patients who get to have their say in engagement activities are not representative of wider patients and publics [57, 58].

Accessing the perspectives of those who do not wish to participate in research is a so called a ‘wicked problem’ [59]. Two of the authors (JF and CP) are now undertaking a qualitative study of patients with one rare disease who have participated in, declined to participate in, or (been) withdrawn from, trials of new medicines and observational studies. We acknowledge, that in our focused study, we are only able to capture the perspective of those have agreed to be interviewed. However, to date we have interviewed patients with experience of participating in clinical trials and patients organisations, as well as those who have refused to participate in a trial, who have been declined the opportunity to participate in a trial because they have not met the inclusion criteria, as well as those who have withdrawn from a trial, and those who are not sure if they have been invited to, or participated in, research.

We suggest that more creative social science and participatory approaches might better enable those who are risk exclusion by traditional health services research methods from participating. See for example the recent initiatives from UK NIHR INCLUDE frameworks for ethnicity, and for people who lack capacity to consent [60].

Through using Brown and Bahri’s framework [12], we detected a lack of breadth in existing qualitative studies, due to the lack of diversity in the patients that have been engaged both socio-economically and geographically, and a narrow focus on the established ways of augmenting, rather than redefining, established clinical trial research [61]. For example, little or no attention in trial design is currently given to the perspectives of patients who do not want to be involved in research. More recently, Galasso and Geiger have suggested that innovation in precision and genomic medicine development risks exacerbating health care inequalities by benefitting people who are already advantaged [62]. They propose a more participatory medicine that would allow a wider public to voice their dissatisfaction, rather than being not- yet-reached or still-not-heard as at present; which might enable a more inclusive and democratic form of innovation [62].

In terms of texture, the third dimension of Brown and Bahri’s framework [12], we identified a lack of attention to both the processes of research and processes of engagement. This is important because, as Brown and Bahri suggest, understanding the processes of reactions to a new indication, the mediating factors of experience (e.g. trust, time, and resources), and any unintended consequences or barriers, are crucial to the design of effective measures and analyses of outcomes [12]. For example, although COVID has brought new opportunities for the use of remote and digital technologies for trial designs in rare diseases [63], attention must also be paid to which patients risk being further disenfranchised by the introduction of these methods.

Qualitative research is rooted in the philosophy of interpretivism, and may employ a range of methodological approaches that enable the interrogation of people’s views and perspectives, as well as any taken-for granted assumptions that may inform or provoke them [64]. We identified an absence of methodological frameworks to inform the research design and instead authors employed generic or off-the-shelf methods (such as ‘interviews’) [65], with some authors taking the patient and public perspectives at face value rather than providing an analysis [42]. Only one paper provided a methodological framework to inform data collection and analysis [35], and none engaged with the principle of reflexivity. Thus, absence in the detail and nature of the relationship between the researcher and researched ensured that any power dynamics involved typically remained obscured [66].

Considering the motives for the research were often to explore patient and caregiver perspectives, it is noteworthy that none of the studies were co-designed with patients or caregivers, nor patient-led. None of the papers reported critical reflection on the mechanisms of engagement activities [67,68,69], and instead presented case-studies as a sufficient reporting mechanism [56]. We contend that the texture of patient and public engagement in orphan drug development would be considerably improved if those researching their experiences and perspectives employed qualitative methodology, rather than ad-hoc methods, and ensured that the processes and outcomes of engagement are fit for purpose (e.g. inclusive and impactful).

In sum, we were able to identify an uneven landscape in the topography of public engagement that is indicative of both the complexity of researching rare diseases in different health care systems and using trial designs, but also the importance of structural inequalities. Data are ‘missing’ from our analysis, because of the methodological weaknesses in the papers or because some kinds of patient are absent from activities conducted with established patient organisations. However, our qualitative synthesis identified several key concerns of patients and has enabled us to suggest how future researchers may address the gaps identified (Fig. 4).

Strength and limitations

A limitation of this research is that a wider literature search may have enabled us to understand more fully the landscape of how patients and other members of the public are currently engaged in orphan drug development. Furthermore, that the findings of our analysis were not robust enough for us to undertake a meta-ethnography is not indicative of failure. Having employed relevant search filters, and then focused upon the four highly discriminating methodological MeSH terms, we were able to evaluate any methodological weaknesses, using validated tools, and discern the substantive contributions in arguably the most relevant examples in the current qualitative literature.

A strength of this research is that we engaged with stakeholders throughout the research process. This included regular input into the design and content of the research from the Patient Advisory Group and steering meetings, as well as in presentations to industry partners and with colleagues working in clinical practice. This has enabled us to make some pragmatic recommendations about both the conduct of qualitative research and public engagement.

Conclusion

Conducting a qualitative synthesis of how patients and other members of the public engage with the orphan drug development, informed by Brown and Bahri’s framework, enabled us to identify the explicit need for methodological rigour in research with patients with rare diseases. This includes the need for appropriate and innovative use of qualitative methods and distinct PPI activities (rather than their conflation) and more strenuous efforts to capture the perspectives of under-served -researched or seldom-listened to communities with experience of rare diseases. This latter focus will require more creative recruitment and wider adoption of post-colonial practises, and a re-alignment of the research agenda (to encourage the use of co-design to enable patients to set the agenda, rather than respond to what they are being offered).

Availability of data and materials

The datasets used and/or analysed during the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

References

Denton N, Molloy M, Charleston S, et al. Data silos are undermining drug development and failing rare disease patients. Orphanet J Rare Dis. 2021;16:161. https://doi.org/10.1186/s13023-021-01806-4).

Directive 2001/20/EC of the European Parliament and the Council of 4 Apr 2001 on the approximation of laws, regulations and administrative provisions of the Member States relating to the implementation of good clinical practice in the conduct of clinical trials on medicinal products for human use. Off J Eur Commun. 2001, L121.

Regulation (EU) No 536/2014 of the European Parliament and the Council of 16 April 2014 on clinical trials on medicinal products for human use, and repealing Directive 2001/20/EC (Text with EEA relevance). Off J Eur Commun. 2014. L 158/1.

Department of Health & Social Care. The UK Rare Diseases Framework. 2021. https://assets.publishing.service.gov.uk/government/uploads/system/uploads/attachment_data/file/950651/the-UK-rare-diseases-framework.pdf.

Dahabreh IJ, Hayward R, Kent DM. Using group data to treat individuals: understanding heterogeneous treatment effects in the age of precision medicine and patient-centred evidence. Int J Epidemiol. 2016;45(6):2184–93.

Kraft SA, Cho MK, Gillespie K, Halley M, Varsava N, Ormond KE, Luft HS, Wilfond BS, Lee SS. Beyond consent: building trusting relationships with diverse populations in precision medicine research. Am J Bioeth. 2018;18(4):3–20.

Carroll JC, Makuwaza T, Manca DP, Sopcak N, Permaul JA, O’Brien MA, Heisey R, Eisenhauer EA, Easley J, Krzyzanowska MK, Miedema B. Primary care providers’ experiences with and perceptions of personalized genomic medicine. Can Fam Physician. 2016;62(10):e626–35.

Roberts JS, Robinson JO, Diamond PM, Bharadwaj A, Christensen KD, Lee KB, Green RC, McGuire AL. Patient understanding of, satisfaction with, and perceived utility of whole-genome sequencing: findings from the MedSeq Project. Genet Med. 2018;20(9):1069–76.

Tran VT, Barnes C, Montori VM, Falissard B, Ravaud P. Taxonomy of the burden of treatment: a multi-country web-based qualitative study of patients with chronic conditions. BMC Med. 2015;13(1):1–5.

Kiefer P, Kirschner J, Pechmann A, Langer T. Experiences of caregivers of children with spinal muscular atrophy participating in the expanded access program for nusinersen: a longitudinal qualitative study. Orphanet J Rare Dis. 2020;15(1):1–9.

Morgan SG, Bathula HS, Moon S. Pricing of pharmaceuticals is becoming a major challenge for health systems. Bmj. 2020;368.

Brown P, Bahri P. ‘Engagement’ of patients and healthcare professionals in regulatory pharmacovigilance: establishing a conceptual and methodological framework. Eur J Clin Pharmacol. 2019;75(9):1181–92.

International Committee of Medical Journal Editors. Recommendations for the Conduct, Reporting, Editing, and Publication of Scholarly work in Medical Journals. https://www.icmje.org/recommendations/. Accessed 03 Nov 2022.

Zhao S. Meta-theory, meta-method, meta-data analysis: what, why and how? Sociol Perspect. 1991;34:377–90.

Young A, Menon D, Street J, Al-Hertani W, Stafinski T. Exploring patient and family involvement in the lifecycle of an orphan drug: a scoping review. Orphanet J Rare Dis. 2017;12(1):1–4.

Lanar S, Acquadro C, Seaton J, Savre I, Arnould B. To what degree are orphan drugs patient-centered? A review of the current state of clinical research in rare diseases. Orphanet J Rare Dis. 2020;15(1):1–8.

Rogers M, Bethel A, Boddy K. Development and testing of a medline search filter for identifying patient and public involvement in health research. Health Inf Libr J. 2017;34(2):125–33.

Wong S, Wilczynki, Haynes R, Hedges Team. Developing optimal search strategies for detecting clinically relevant qualitative studies in MEDLINE. Stud Health Technol Inform. 2004;107(1):311–6.

Malterud K, Siersma V, Guassora A. Sample Size in Qualitative Interview Studies: Guided by Information Power. Qual Health Res. 2016;26(13):1753–60.

Clarivate Analytics Endnote X8. 2016.

Critical Appraisal Skills Programme. CASP Qualitative Checklist. 2018. Available at: https://casp-uk.net/casp-tools-checklists/ Accessed 1 June 2021.

Campbell R, Pound P, Morgan M, Daker-White G, Britten N, Pill R, et al. Evaluating metaethnography: systematic analysis and synthesis of qualitative research. Health Technol Assess. 2011;15(43).

Dixon-Woods M, Sutton A, Shaw R, Miller T, Smith J, Young B, Bonas S, Booth A, Jones D. Appraising qualitative research for inclusion in systematic reviews: a quantitative and qualitative comparison of three methods. J Health Serv Res Policy. 2007;12(1):42–7.

Toye F, Seers K, Allcock N, Briggs M, Carr E, Barker K. Meta-ethnography 25 years on: challenges and insights for synthesising a large number of qualitative studies. BMC Med Res Methodol. 2014;14(1):1–4.

Campbell R, Pound P, Pope C, Britten N, Pill R, Morgan M, Donovan J. Evaluating meta-ethnography: a synthesis of qualitative research on lay experiences of diabetes and diabetes care. Soc Sci Med. 2003;56:671–84.

Tong A, Sainsbury P, Craig J. Consolidated criteria for reporting qualitative research (COREQ): a 32-item checklist for interviews and focus groups. Int J Qual Health Care. 2007;19(6):349–57.

Noblit GW, Hare RD, Hare RD. Meta-ethnography: synthesizing qualitative studies. sage; 1988.

Malpass A, Shaw A, Sharp D, Walter F, Feder G, Ridd M, Kessler D. “Medication career” or “moral career”? The two sides of managing antidepressants: a meta-ethnography of patients’ experience of antidepressants. Soc Sci Med. 2009;68(1):154–68.

France EF, Cunningham M, Ring N, Uny I, Duncan EA, Jepson RG, Maxwell M, Roberts RJ, Turley RL, Booth A, Britten N. Improving reporting of meta-ethnography: the eMERGe reporting guidance. BMC Med Res Methodol. 2019;19(1):1–3.

Malpass A, Shaw A, Sharp D, Walter F, Feder G, David KD. ‘“Medication career”’ or ‘“Moral career”’? The two sides of managing antidepressants: A meta-ethnography of patients’ experience of antidepressants. Soc Sci Med. 2009;68:154–68.

Popay J, Roberts H, Sowden A, Petticrew M, Arai L, Rodgers M, Britten N, Roen K, Duffy S. Guidance on the conduct of narrative synthesis in systematic reviews. Prod ESRC Methods Program Version. 2006;1(1): b92.

Miles MB, Huberman AM, Saldaña J. Qualitative data analysis: a methods sourcebook. Sage Publications; 2018.

Bendixen RM, Morgenroth LP, Clinard KL. Engaging participants in rare disease research: a qualitative study of Duchenne muscular dystrophy. Clin Ther. 2016;38(6):1474–84.

Carroll R, Antigua J, Taichman D, Palevsky H, Forfia P, Kawut S, Halpern SD. Motivations of patients with pulmonary arterial hypertension to participate in randomized clinical trials. Clin Trials. 2012;9(3):348–57.

Gengler AM. “I want you to save my kid!” illness management strategies, access, and inequality at an elite university research hospital. J Health Soc Behav. 2014;55(3):342–59.

Kesselheim AS, McGraw S, Thompson L, O’Keefe K, Gagne JJ. Development and use of new therapeutics for rare diseases: views from patients, caregivers, and advocates. Patient Centered Outcomes Res. 2015;8(1):75–84.

Peay HL, Tibben A, Fisher T, Brenna E, Biesecker BB. Expectations and experiences of investigators and parents involved in a clinical trial for Duchenne/Becker muscular dystrophy. Clin Trials. 2014;11(1):77–85.

Menon D, Stafinski T, Dunn A, Wong-Rieger D. Developing a patient-directed policy framework for managing orphan and ultra-orphan drugs throughout their lifecycle. Patient Centered Outcomes Res. 2015;8(1):103–17.

Tingley K, Coyle D, Graham ID, Sikora L, Chakraborty P, Wilson K, Mitchell JJ, Stockler-Ipsiroglu S, Potter BK. Using a meta-narrative literature review and focus groups with key stakeholders to identify perceived challenges and solutions for generating robust evidence on the effectiveness of treatments for rare diseases. Orphanet J Rare Dis. 2018;13(1):1–9.

Tingley K, Coyle D, Graham ID, Chakraborty P, Wilson K, Potter BK. Stakeholder perspectives on clinical research related to therapies for rare diseases: therapeutic misconception and the value of research. Orphanet J Rare Dis. 2021;16(1):1–1.

Young A, Menon D, Street J, Al-Hertani W, Stafinski T. Engagement of Canadian patients with rare diseases and their families in the lifecycle of therapy: a qualitative study. Patient Centered Outcomes Res. 2018;11(3):353–9.

Gaasterland CM, Jansen-van der Weide MC, Vroom E, Leeson-Beevers K, Kaatee M, Kaczmarek R, Bartels B, van der Pol WL, Roes KC, van der Lee JH. The POWER-tool: recommendations for involving patient representatives in choosing relevant outcome measures during rare disease clinical trial design. Health Policy. 2018;122(12):1287–94.

Gaasterland CM, van der Weide MC, du Prie-Olthof MJ, Donk M, Kaatee MM, Kaczmarek R, Lavery C, Leeson-Beevers K, O’Neill N, Timmis O, Van Nederveen V. The patient’s view on rare disease trial design—a qualitative study. Orphanet J Rare Dis. 2019;14(1):1–9.

Lopes MT, Koch VH, Sarrubbi-Junior V, Gallo PR, Carneiro-Sampaio M. Difficulties in the diagnosis and treatment of rare diseases according to the perceptions of patients, relatives and health care professionals. Clinics. 2018;5:73.

Li X, Lu Z, Zhang J, Zhang X, Zhang S, Zhou J, Li B, Ou L. The urgent need to empower rare disease organizations in China: an interview-based study. Orphanet J Rare Dis. 2020;15(1):1–9.

Geissler J, Ryll B, di Priolo SL, Uhlenhopp M. Improving patient involvement in medicines research and development: a practical roadmap. Therap Innov Regul Sci. 2017;51(5):612–9.

Witham MD, Anderson E, Carroll C, et al. Developing a roadmap to improve trial delivery for under-served groups: results from a UK multi-stakeholder process. Trials. 2020;21:694. https://doi.org/10.1186/s13063-020-04613-7.

Halliday M, Mill D, Johnson J, Lee K. Online focus group methodology: recruitment, facilitation, and reimbursement. In: Desselle S, Garcia Cardenas V, Anderson C, Aslani P, Chen A, Chen T, editors. Contemporary research methods in pharmacy and health services. Elsevier Press; 2022. p. 433–45.

Renfro CP, Hohmeier K. Rapid turn-around qualitative analysis applications in pharmacy and health services research. In: Desselle S, GarciaCardenas V, Anderson C, Aslani P, Chen A, Chen T, editors. Contemporary research methods in pharmacy and health services. Elsevier Press; 2022. p. 397–405.

Cavaller-Bellaubi M, Faulkner SD, Teixeira B, Boudes M, Molero E, Brooke N, McKeaveney L, Southerton J, Vicente MJ, Bertelsen N, García-Burgos J. Sustaining meaningful patient engagement across the lifecycle of medicines: a roadmap for action. Therap Innov Regul Sci. 2021;55(5):936–53.

du Plessis D, Sake JK, Halling K, Morgan J, Georgieva A, Bertelsen N. Patient centricity and pharmaceutical companies: is it feasible? Therap Innov Regul Sci. 2017;51(4):460–7.

Baggott R, Jones K. The voluntary sector and health policy: the role of national level health consumer and patients’ organisations in the UK. Soc Sci Med. 2014;1(123):202–9.

Huyard C. How did uncommon disorders become ‘rare diseases’? History of a boundary object. Sociol Health Illn. 2009;31(4):463–77.

Huyard C. Who rules rare disease associations? A framework to understand their action. Sociol Health Illn. 2009;31(7):979–93.

Pinto D, Martin D, Chenhall R. Chasing cures: rewards and risks for rare disease patient organisations involved in research. BioSocieties. 2018;13(1):123–47.

Deal LS, Goldsmith JC, Martin S, Barbier AJ, Roberds SL, Schubert DH. Patient voice in rare disease drug development and endpoints. Therap Innov Regul Sci. 2017;51(2):257–63.

Chalasani M, Vaidya P, Mullin T. Enhancing the incorporation of the patient’s voice in drug development and evaluation. Res Involv Engag. 2018;4(1):1–6.

Sine S, de Bruin A, Getz K. Patient engagement initiatives in clinical trials: recent trends and implications. Therap Innov Regul Sci. 2021;55(5):1059–65.

Lavery JV. ‘Wicked problems’, community engagement and the need for an implementation science for research ethics. J Med Ethics. 2018;44:163–4.

NIHR. Improving inclusion of under-served groups in clinical research: Guidance from the NIHR-INCLUDE project. UK: NIHR; 2020. Available at: www.nihr.ac.uk/documents/improving-inclusion-of-under-served-groups-in-clinical-research-guidance-from-include-project/25435. Accessed 03 Nov 2022.

Galasso I, Geiger S. Preventing ‘exit’, eliciting ‘voice’: patient, participation, and public involvement as ‘invited activism’ in precision medicine and genomic initiatives. In: Geiger S, editor. Healthcare activism: markets, morals and the collective good. Oxford University Press; 2021.

Moore J, Goodson N, Wicks P, Reites J. What role can decentralized trial designs play to improve rare disease studies? Orphanet J Rare Dis. 2022;17(1):1–4.

Gregg A, Getz N, Benger J, Anderson A. A novel collaborative approach to building better clinical trials: new insights from a patient engagement workshop to propel patient-centricity forward. Therap Innov Regul Sci. 2020;54(3):485–91.

Pope C, Mays N, editors. Qualitative research in health care. Oxford: Wiley Blackwell; 2020.

Caelli K, Ray L, Mill J. ‘Clear as mud’: toward greater clarity in generic qualitative research. Int J Qual Methods. 2003;2(2):1–3.

Berger R. Now I see it, now I don’t: researcher’s position and reflexivity in qualitative research. Qual Res. 2015;15(2):219–34.

Oliver SR, Rees RW, Clarke-Jones L, Milne R, Oakley AR, Gabbay J, Stein K, Buchanan P, Gyte G. A multidimensional conceptual framework for analysing public involvement in health services research. Health Expect. 2008;11(1):72–84.

Staniszewska S, Brett J, Simera I, Seers K, Mockford C, Goodlad S, Altman DG, Moher D, Barber R, Denegri S, Entwistle A. GRIPP2 reporting checklists: tools to improve reporting of patient and public involvement in research. Bmj. 2017;358.

Greenhalgh T, Hinton L, Finlay T, Macfarlane A, Fahy N, Clyde B, Chant A. Frameworks for supporting patient and public involvement in research: systematic review and co-design pilot. Health Expect. 2019;22(4):785–801.

Acknowledgements

We thank all of the patients, clinicians and industry members who participated in the Patient Advisory Group (PAG) and steering meetings, as part of this research. We thank Simon Briscoe who developed the search strategy and undertook the searches.

Funding

This work was supported by the Medical Research Council MR/W003732/1. For the purpose of open access, the author has applied a ‘Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) licence to any Author Accepted Manuscript version arising’ (where permitted by UKRI, ‘Open Government Licence’ or ‘Creative Commons Attribution No-derivatives (CC BY-ND) licence may be stated instead.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

JF and CP designed the study, were responsible for its conduct, and obtained funding. JF conducted the data collection and JF, AH, ET conducted the data analysis, with SL and JM sharing clinical insights. All authors commented on the manuscript and agreed the final version. JF is the guarantor. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate

Not applicable.

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Competing interests

Authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary Information

Additional file 1. Supplementary material:

Results of highly discriminating search (full texts retrieved)

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/. The Creative Commons Public Domain Dedication waiver (http://creativecommons.org/publicdomain/zero/1.0/) applies to the data made available in this article, unless otherwise stated in a credit line to the data.

About this article

Cite this article

Frost, J., Hall, A., Taylor, E. et al. How do patients and other members of the public engage with the orphan drug development? A narrative qualitative synthesis. Orphanet J Rare Dis 18, 84 (2023). https://doi.org/10.1186/s13023-023-02682-w

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/s13023-023-02682-w