Abstract

Background

Improving care coordination is particularly important for individuals with rare conditions (who may experience multiple inputs into their care, across different providers and settings). To develop and evaluate strategies to potentially improve care coordination, it is necessary to develop a method for organising different ways of coordinating care for rare conditions. Developing a taxonomy would help to describe different ways of coordinating care and in turn facilitate development and evaluation of pre-existing and new models of care coordination for rare conditions. To the authors’ knowledge, no studies have previously developed taxonomies of care coordination for rare conditions. This research aimed to develop and refine a care coordination taxonomy for people with rare conditions.

Methods

This study had a qualitative design and was conducted in the United Kingdom. To develop a taxonomy, six stages of taxonomy development were followed. We conducted interviews (n = 30 health care professionals/charity representatives/commissioners) and focus groups (n = 4 focus groups, 22 patients/carers with rare/ultra-rare/undiagnosed conditions). Interviews and focus groups were audio-recorded with consent, and professionally transcribed. Findings were analysed using thematic analysis. Themes were used to develop a taxonomy, and to identify which types of coordination may work best in which situations. To refine the taxonomy, we conducted two workshops (n = 12 patients and carers group; n = 15 professional stakeholder group).

Results

Our taxonomy has six domains, each with different options. The six domains are: (1) Ways of organising care (local, hybrid, national), (2) Ways of organising those involved in care (collaboration between many or all individuals, collaboration between some individuals, a lack of collaborative approach), (3) Responsibility for coordination (administrative support, formal roles and responsibilities, supportive roles and no responsibility), (4) How often appointments and coordination take place (regular, on demand, hybrid), (5) Access to records (full or filtered access), and (6) Mode of care coordination (face-to-face, digital, telephone).

Conclusions

Findings indicate that there are different ways of coordinating care across the six domains outlined in our taxonomy. This may help to facilitate the development and evaluation of existing and new models of care coordination for people living with rare conditions.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

The complexity of the organisation and delivery of health care has been further complicated in recent years, due to the need to manage a higher demand for health care and the introduction of new technologies, increased availability of treatments and provision of care across many settings [1]. These changes and demand on health care may make it difficult for health care organisations to manage care [1], for providers to deliver care, and may make it more burdensome for patients to receive and engage with their care [2,3,4]. One potential solution to these challenges is to consider and further develop models of care, such as care coordination [1]. Enhanced coordination is particularly beneficial for those with complex conditions such as chronic [2, 4] and rare conditions [3, 5,6,7,8]. Rare, ultra-rare and undiagnosed conditions are often complex, and affect multiple body systems and a person’s mental and physical health [9, 10]. Rare conditions require care from multiple sectors, and health care professionals. For example, patients may be seen by primary care, secondary care, tertiary and quaternary care providers. Whilst individually rare conditions only affect a few individuals (each condition affects up to five in 10,000 people) [6, 9], collectively the 6000–8000 rare and ultra-rare conditions together with undiagnosed conditions affect a significant proportion of individuals worldwide [11].

Previous research has indicated that a lack of coordination has many negative impacts on patients and carers living with rare conditions, including on their physical health, finances, psychological wellbeing, and social aspects of their lives [12]. A recent scoping review of 154 reviews of common and rare chronic conditions, together with focus groups with patients, carers and health care professionals, has defined care coordination for rare conditions [13]. Findings indicated that coordination for rare conditions has many components and that there are many different options for how care can be coordinated [13]. Coordination was defined as everyone involved in a person’s care (including the patient and/or family members) working together across multiple aspects of care to avoid duplication and achieve shared outcomes. Coordination would need to be lifelong and involve all parts of the health and social care system (including different services, settings, multiple conditions, and transition between services). It has been argued that coordination should be family-centred, evidence-based and ensure equal access for all [13]. The review highlighted many different components of coordination, including components that need to be coordinated (e.g., assessment), components that inform how to coordinate care (e.g., someone to take responsibility), components that have multiple roles (e.g., planning) and components that contextualise coordination (e.g., evidence-based practice) [13].

In order to better understand and potentially improve care coordination, it is necessary to identify and describe the different ways in which care can be coordinated for rare conditions. One way to facilitate the organisation of care coordination is to develop a taxonomy of care coordination for rare conditions. Taxonomies are systems used to organise complex concepts into common conceptual domains and dimensions based on similarities [14, 15]. Developing a taxonomy of care coordination for rare conditions would help to describe different ways of coordinating care. This in turn can facilitate the development and evaluation of pre-existing and new models of care coordination.

Taxonomies aim to provide clear definitions [15], and have been previously used to organise complex health care concepts including taxonomies of integrated care [16], health care [17], behaviour change [18], and the burden of treatment for patients with chronic conditions [19]. For example, the burden of treatment taxonomy included tasks that the health care system imposes on patients, factors worsening the burden of treatment and consequences of burden from the patients’ point of view [19].

To the authors’ knowledge, no previous studies have attempted to develop a taxonomy of coordination of care specifically for rare or chronic conditions. This study aimed to develop and refine a taxonomy of care coordination for people living with rare conditions, based on learning from the UK healthcare context and the National Health Service. Whilst there are many different rare conditions and the care needs for each of these may differ slightly, it is necessary to develop a taxonomy that can be used to outline the different options and then these options can be adapted and applied to suit different contexts and different rare, ultra-rare and undiagnosed conditions. We present our findings on what types of coordination may be appropriate in different situations and the development of hypothetical models of care coordination separately [20].

Methods

This study is part of a larger mixed-methods research project which aims to explore coordination of care for people living with rare conditions [21]. This study builds on previous aspects of this study [12, 13].

A summary of the methods used in this study are provided below (see Table 1 for a detailed description).

Design

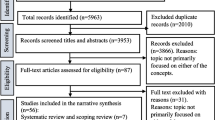

A two-stage study using qualitative methods was conducted (see Fig. 1). In stage one, interviews and focus groups were conducted to develop a taxonomy. In stage two, workshops were conducted to refine the taxonomy.

Setting

Our study explored care coordination in the UK, across different sectors; with a focus on health care and the National Health Service.

Sample

Participants were recruited purposively using a range of methods including advertisements throughout the voluntary sector and advertisements through our partnership with four NHS sites. We recruited a range of individuals with experience of rare conditions, including patients, parents/carers, and professionals (health care professionals, charity representatives and commissioners). Participants took part in interviews (n = 30 professionals), focus groups (four groups of 6–8 patients/carers) [27] and workshops (one patient/carer, and one professional; approximately 15 participants in each workshop). For patients and carers, we selected participants based on the area of the UK they lived in, their condition, role, age, and experience with different types of care coordination. For healthcare professionals, charity representatives and commissioners, we selected participants based on the area of the UK they worked in, their job role (to reflect a range of different job roles) and experience of different types of coordination. Eligibility criteria, recruitment methods and sampling criteria are provided in Table 1.

Procedure

Study adverts included details of the researcher’s contact details and asked individuals to get in touch via email or telephone. Interested individuals contacted the researcher and were provided with an information sheet. Participants were asked to sign consent forms in advance of the interviews, focus groups and workshops. Participants were informed that their data would be kept confidential, fully anonymised and that they could withdraw without reason.

To develop the taxonomy, one researcher (HW) conducted interviews with health care professionals, commissioners and charity representatives. Two researchers (HW/AS), with a third observer (EH) conducted four focus groups with patients and carers (two face-to-face and two virtual). Interviews and focus groups were recorded with consent, professionally transcribed, checked for accuracy and fully anonymised. To develop the taxonomy and identify different ways of coordinating care, we used an interview topic guide and a focus group topic guide (Additional file 1: Appendix S1). See Table 1 for further details.

To refine the taxonomy, we held workshops with patients, carers, health care professionals, charity representatives and commissioners. We developed a workshop topic guide (Additional file 2: Appendix S2) to determine if the findings were appropriate and comprehensive. Workshop participants were sent a video outlining the findings prior to the workshops. Participants were split into three breakout groups and asked to discuss the findings for each of the six taxonomy domains. Workshops were recorded and notes were taken. Notes from the workshop were also used to produce a graphical representation of findings.

For a more detailed description of our procedure, please see Table 1.

Analysis

Thematic analysis was used to analyse interview and focus group data. In line with recommendations for taxonomy development [15]. Inductive coding was used to develop the coding framework [29]. Two researchers (HW/AS) initially coded six interview transcripts to develop and agree a coding frame. The coding framework was then used to code all interview and focus group transcripts by one researcher (HW). A second researcher (AS) also coded 20% of the data. Findings were discussed and agreed. Findings were then grouped into themes and sub-themes. Given the large amount of data, this was done in two stages: (1) development of themes and sub-themes for the data on aspects of coordination (to develop initial taxonomy options), (2) development of themes and sub-themes for findings relating to which models of care coordination work in different situations (described in [20]). Themes were discussed by co-authors and used to develop a taxonomy. Findings were also used to explore which models of care coordination may be appropriate in different situations and to develop hypothetical models of care coordination (these findings are described elsewhere in [20]).

Once themes and sub-themes had been developed, we followed six stages of taxonomy development to develop the proposed taxonomy [32]: (1) Identify the meta-characteristic (focus of the taxonomy), (2) Identify ending conditions, (3) Choose approach, (4) Identify a subset of objects to classify, (5) Identify common characteristics and (6) Group the characteristics [14]. Table 2 outlines how we applied these six steps.

To refine the taxonomy, we coded workshop notes and grouped them into themes (see Additional file 3: Appendix S3 for a visual representation of workshop findings). Findings were used to amend the taxonomy. See Table 1 for further details.

Results

Participant characteristics

This study included 77 different participants (two participants took part in both a workshop and interview/focus group). Participants included patients, carers, health care professionals, commissioners and charity representatives. Overall, data from 52 participants (30 individual interviews, 22 focus group participants) informed the development of the taxonomy. Data from 27 workshop participants informed the refinement of the taxonomy. Demographic characteristics are shown in Table 3.

Whilst it would not have been possible to represent all 6000–8000 conditions within our study, the patients, carers, healthcare professionals, charity representatives and commissioners that took part in our study were selected to represent a range of different rare conditions (including different characteristics, presentations, and models of care coordination). Additionally, professionals, charity representatives and commissioners were able to draw upon experiences of working across different types of rare conditions. Examples of groups of rare conditions included in this study included rare skin conditions, rare chromosome conditions and rare autoinflammatory conditions. We sampled a range of different rare, ultra-rare and undiagnosed conditions to ensure that our sample was as representative of care coordination for rare conditions as possible. We included a range of different professionals with different job roles in our study, including health and social care professionals (e.g. consultants from different disciplines, allied health professionals, genetic counsellors, pharmacists, psychiatrists, GPs), charity representatives (with various roles) and national and local commissioners (see Table 3 for details).

Taxonomy of care coordination for rare conditions

Our final taxonomy of care coordination consists of six domains: (1) ways of organising care; (2) ways of organising those involved in a patient’s care; (3) responsibility for coordination; (4) how often appointments and coordination take place; (5) access, and (6) mode (see Table 4). Each domain outlines different ways of coordinating care (labelled ‘sub-domains’). Within each way of coordinating care there are different options (labelled ‘options’).

Within the next section we will present each of the taxonomy domains and their sub-domains in turn. Example quotes for each of the six domains are shown in Table 5.

Domain 1. Ways of organising care

Our findings highlighted different ways of organising care. Options ranged from local care provision where all care is delivered locally, through to care being delivered in a single national centre that serves all patients in the country with a particular rare condition. Figure 2 provides a summary of the different ways of organising care.

Nationally centralised

For nationally centralised services, we identified different examples of nationally centralised care where care is delivered or coordinated centrally. Central delivery of care can either take place in one nationally commissioned centre/service (such as rare disease centres or condition-specific centres) or a network of multiple services or centres.

Hybrid

We also identified some ‘hybrid’ options, which combine both national or regional specialist and local care. Hybrid options include hub and spoke networks, and outreach. There are different types of hub and spoke models. For example, in one type of hub and spoke model of care, the national centre or centres (hub) coordinate care but the actual care delivery happens at a local hospital or GP (spokes). In other types of hub and spoke models, the national centre (hub) provides some care delivery, but other aspects of care are delivered at local hospitals or GPs (spokes). There are also different types of outreach models. Examples of outreach models include outreach clinics (e.g. local outreach clinic, specialists travelling to provide joint clinics with local team, specialists providing care locally) and outreach relating to care coordination (e.g. outreach model of clinical case management in mental health practice, coordinator doing outreach work with local providers and GP and coordinator travelling to provide care locally). Outreach models relating to education included specialist teams providing support for local teams (e.g., education to raise awareness, providing guidance and supervision, email hotline, training, opportunities for local providers to shadow clinics, and formalised agreements that specialists will answer GP queries).

Local

Findings highlighted the importance of specialists being involved in care for rare conditions. However, findings also indicated that routine care and non-standardised or tailored care should be delivered locally, and that regular contact with local professionals would be useful. On the other hand, some focus group participants reported wanting all of their care to be delivered locally, or regionally. For some, there was a lack of local care provided.

Domain 2. Ways of organising those involved in a patient’s care

Our findings highlighted different ways of organising those involved in a patient’s care (including professionals involved in a patient’s care, the patient and their family). This includes two types of collaboration: collaborative working between professionals, and collaborative working between professionals, patients and carers. Options ranged from collaboration between many or all of the individuals involved in a patient’s care, to collaboration between some of the individuals involved in a patient’s care, to a lack of collaborative working (see Table 4 for examples). Workshop findings highlighted that COVID-19 may have offered new opportunities for collaboration, such as the ability for local team members to dial into multidisciplinary team meetings. Figure 3 provides a summary of the different ways of organising teams.

Collaboration between many or all of those involved in a patient’s care

Examples of collaboration between many or all of the individuals involved in a patient’s care includes condition specific clinics (for example those organised and led by individual health care professionals and those delivered as rare disease or specialist clinics) and multidisciplinary meetings held between all professionals (and the patient/carer where appropriate). Different types of condition-specific clinics exist, ranging from: multidisciplinary team appointments including all professionals (and the patient/carer where appropriate); one stop shops where patients receive all care in one place at the same time; multidisciplinary clinics that involve professionals seeing patients both together as a team but also separately; and carousel clinics whereby the health care professional moves around whilst the patient stays in the same room.

Collaboration between some of those involved in a patient’s care

One example of collaboration between some of the professionals involved in a patient’s care is joint clinics. Joint clinics consist of a couple of professionals working together to provide care. For example, joint clinics consisting of an adult and a child provider; joint clinics consisting of multiple consultants; and joint clinics consisting of specialist and local providers. Additionally, close working between different professionals may occur (e.g. paediatrician contacting adult provider when the patient is ready to transition to adult care).

Lack of collaborative working

In some cases, examples demonstrating a lack of collaborative working between those involved in a patient’s care were identified, including a lack of multidisciplinary team clinic, lack of transition methods and lack of ownership.

Domain 3. Types of responsibilities and roles needed for care coordination

Our findings highlighted different types of responsibility and roles involved in coordinating care for rare conditions (administrative, formal and supportive roles) across health care, social care and voluntary sectors. Figure 4 provides a summary of the different types of responsibility and roles.

Administrative support

Administrative support for appointment organisation was highlighted as important. Additionally, having a point of contact for patients and having a point of contact for other professionals was felt to be important. Some patients and carers highlighted that they do not currently have a point of contact. Different options were highlighted in relation to who should provide administrative support (e.g. administrator and patient/carer, administrator, charities, automated support) and who should be the point of contact for patients (e.g. clinicians, administrators, charity workers).

Formal coordination responsibilities

Formal coordination responsibilities across three roles were identified: (1) those conducted by a coordinator, (2) those conducted by a clinical lead in secondary/tertiary care, and (3) those conducted by a GP in primary care.

Our findings highlighted many roles of a care coordinator (e.g., liaising with health care professionals, coordinating the MDT and aspects of care across different sectors, trusted named person for the patient, ownership, quality assurance and planning). Many different types of coordinators were identified: (1) administrative coordinators, (2) care coordinators and (3) clinical coordinators. Administrative coordinators are individuals who arrange MDTs and clinics (e.g. patient/carers, non-medical professionals, charity employed social workers, nurse or allied health professionals). Care coordinators are individuals who have a formal/professional role for coordinating care in addition to system and condition knowledge (e.g. specialist nurses, allied health professionals, hospice/community nurses, social care professionals, non-medical professionals, charity employed social workers and transition coordinators). Clinical coordinators are individuals with sufficient clinical expertise to coordinate complex cases (e.g. doctors or GPs).

Our findings highlighted many roles of a clinical lead, including overseeing or managing care in a service, clinical case management, supervision of professionals, decision-making about extent to which different levels of coordinator are needed, and delegating and ensuring accountability of responsibilities. Clinical leads were identified from a range of roles (e.g. consultants, discipline-specific clinical leads, paediatricians (e.g., hospital/community), the patient’s favourite doctor, a specialist nurse, or geneticists). Some patients and carers reported that they did not have a clinical lead responsible for their care.

Findings highlighted that GPs may have the potential to be involved in coordination in numerous ways, including as a coordinator (e.g. making appointments, named coordinator, developing care plans, identifying when patients need to see coordinator), clinical lead (e.g. a role between primary care and tertiary care to enable them to be responsible for care, or having a GP equivalent role for rare conditions), and implementing care plans provided by specialists (e.g. gatekeeper for specialist care referrals, providing local care and implementing care plans). However, findings indicate that many GPs do not take ownership and that some patients do not have a named GP. A lack of communication between GPs and specialists indicated a need for further collaboration between GPs and specialists (e.g., involvement in MDTs, working in hospital settings, receiving training by specialists, formalised contracts, point of contact).

Supportive roles

Supportive roles were also identified, including those conducted by charities/patient organisations and carers and those conducted by patients/carers (see Table 4).

Findings indicated that charities/patient organisations play many roles in coordination including supporting coordination by providing support to patients/carers (e.g. providing information, holding support groups, providing helplines) and professionals (e.g. training of professionals and guiding coordinators). Charities also have direct roles in coordination (e.g. funding coordinator posts and clinical networks, being clinic coordinators, coordinating care, providing resources to help coordinate care, and managing registries). Whilst charities provide funding currently there were views that charities should not be filling gaps for health care services and that charities may not have the capacity to be the main coordinator. Additionally, charities play a role in service quality and improvement (e.g., care pathway development, pulling together evidence, identifying weaknesses in coordination, and setting up/developing specialist services).

Findings indicated that patients and carers currently have lots of direct involvement in coordinating care. Patients and carers act as coordinators of care (e.g. coordinating care across multiple hospitals, being their own advocates, taking more responsibility and chasing appointments) or collaborate with health care professionals to coordinate care (e.g. to arrange appointments, support from health care professionals for coordination as and when needed, and wanting care to be coordinated in partnership with themselves). Patients and carers also support transition to adult services, provide education to health care professionals, and monitor their own care.

Domain 4. How often care appointments and coordination take place

Our findings highlighted different time periods for care appointments and coordination activities. Options included regular appointments, on demand appointments and hybrid of regular and on demand appointments (see Table 3). Workshop findings highlighted that COVID-19 may have provided more opportunities for on demand appointments for those with stable conditions. See Fig. 5 for a summary of this domain.

Regular

Regular appointments were discussed in relation to: frequency of regular specialist centre appointments (ranging from six weeks post treatment to every 18 months), frequency of regular care appointments (ranging from multiple appointments in one week to every 6 months), frequency of contact (ranging from monthly check-ins to yearly check ins), frequency of outreach visits (e.g. annually), frequency of contact with coordinator (ranging from monthly to annually) and frequency of MDT meetings between health care professionals (ranging from weekly to twice a year). Participants indicated that the regularity of appointments is and should be guided by condition-specific guidelines (where available).

On demand

Findings from some focus group participants and some interviewees indicated that on demand contact or care appointments (with specialists and coordinators) may be better than regular contact for some patients. One caveat to on demand appointments was that there needs to be quick access to expertise and care in emergencies.

Hybrid

Workshop findings highlighted the need for a hybrid category that combines both regular care (at a minimum) with on demand support.

Domain 5. Access to records

Our findings highlighted different types of access. Options ranged from full or restricted access to records for patients and providers and access to support for patients and health care professionals (see Table 4).

For patients, findings highlighted the need for patients and carers to have access to their own information. This included: access to their records, and access to meetings concerning them.

For health care professionals, findings indicated the importance of access to information and records, given that patients are often seen in different places and by different professionals. The extent to which health care professionals should access information and records was contested; with some patients and carers thinking that any health care professional involved in care should be able to access records, and others thinking that this access should be limited (e.g., to necessary information such as the information relevant to the current care/condition, rather than all of the patient’s history). Some patients highlighted that they would like to control who has access to this information. Workshop participants highlighted that full access to records with a summary may be helpful.

Domain 6. Mode of contact

Our findings highlighted different modes (see Table 4). Figure 6 provides a summary of this domain.

Information sharing/communication

For information sharing, participants described many different modes, including digital methods, written methods, verbal methods or a lack of information sharing.

Options for digital information sharing included digital records, letters, databases and registries (stored locally, in the cloud or on an app), portals (e.g. national online portals to access records, letters and guidance), mobile applications for patients (e.g. Patient Knows Best app or apps for patients to hold and share information from their records), and patient information. Digital options for communication between professionals (e.g. virtual panels, email hotlines, virtual meetings, email) and between professionals and patients (e.g. email, Whatsapp) were identified.

Many different written methods of information sharing were also identified: (1) written care documentation, (2) service planning, (3) guidelines and pathways. For written care documentation, this included: written records (e.g., condition specific passports and alert cards), letters, care plans (e.g. agreed care plans, education health and care (EHC) plans and transition plans) and reports. For service planning, written methods included plans to specify hospital and professional roles and responsibilities, and standard operating procedures to record MDT working. For guidelines and pathways, this included evidence-based service specifications outlining service standards, quality assurance standards, national guidelines (e.g. NICE or charity produced), international best practice and training policies and frameworks for care coordinators and supervisors.

Telephone was also identified as a mode of communication between professionals (e.g. ringing others to coordinate care, conference calls, discussing treatment plans) and between professionals and patients (e.g. emergency point of contact and telephone advice services).

A lack of information sharing was also highlighted throughout the focus groups and interviews (including a lack of communication between team members and a lack of information sharing).

Care and coordination appointments

In terms of care and coordination appointments and communication, our participants described many different modes, including face to face, digital, phone and a combination of methods.

Face-to-face care delivery was identified for many aspects of care and coordination, including meetings (e.g., team meetings and patient/coordinator meetings), care appointments (e.g. initial patient/professional contact, at key treatment phases such as diagnosis and stabilisation, and for appointments requiring physical examinations) and support (e.g. peer support group meetings, network member meetings, and monitoring from charity nurses).

Digital options for care delivery and coordination appointments were identified. For coordinated care delivery, this included: video appointments with professionals (e.g., Skype, Zoom, WhatsApp, Facetime), virtual centres and MDT clinics, digital monitoring (e.g., electronic wearable devices, apps to record test results), virtual tours of wards, diagnostic technology. For coordination this included: video appointments with coordinators (e.g., Skype, Zoom, Whatsapp, Facetime), coordination in the cloud, and virtual review (as the lowest level of coordination).

Options for telephone care delivery (e.g., clinics/consultations and catch ups) and coordination (e.g. calls with coordinators and introductions) were also discussed. Workshop findings highlighted that COVID-19 has accelerated the shift to digital and telephone delivery of care for people living with rare conditions.

Discussion

Key findings

We have developed a taxonomy of care coordination for rare conditions, based on learning from the UK health system and the National Health Service. We identified six domains of care coordination: (1) ways of organising care (local, hybrid, national); (2) ways of organising those involved in a patient’s care (collaboration between many or all of those involved, collaboration between some of those involved, and a lack of collaborative working); (3) responsibility for coordination (administrative support, formal roles and responsibilities, supportive roles and no responsibility); (4) how often appointments and coordination take place (regular, on demand or hybrid); (5) access (full or filtered access to records), and (6) mode of information sharing, care coordination/delivery and communication.

How findings relate to previous research

These findings extend knowledge on care coordination. National policy documents and previous research have highlighted the importance of care coordination [3, 13, 32]. However, findings indicate that little is known about coordination for rare conditions and what this might entail [13]. Previous research has shown that coordination for rare and common chronic conditions has many components [12, 13, 33, 34], but care coordination had not been formally categorised. The taxonomy presented in this paper extends previous research by formalising care coordination for rare conditions into six domains (each with different options). Whilst previous research has developed taxonomies for related concepts [16,17,18,19], this is the first research that has attempted to develop a taxonomy of care coordination for rare conditions. Findings indicate that whilst different conditions have different characteristics and challenges, it is possible to develop one taxonomy that covers a range of conditions and a range of care coordination options.

Our findings highlighted three main options for organising care, including nationally centralised, hybrid and local care. This supports previous research which has highlighted the importance of specialist centres for people living with rare conditions [35] but extends previous research by demonstrating the potential usefulness of hub and spoke models and outreach models for rare conditions; models which are not new but which have been used in other chronic conditions with success [36,37,38]. Additionally, the findings highlight that local care is not necessarily problematic, with some participants articulating the role of local care and the benefits that this provides them. However, findings do indicate that developing local expertise and knowledge is key.

Our findings on the organisation of professionals and the patient/carer for rare conditions supports previous research that indicates the importance of collaboration and MDTs for rare conditions [12, 39] and other conditions [40]. Findings also support previous research which indicates a need to join up care appointments from different disciplines and hospitals into one appointment (e.g., condition-specific clinics), in order to facilitate coordination [12, 13]. However, findings indicate that collaboration does not always happen in practice and that improvements in collaboration/joined-up working are needed. However, there have been some recent initiatives to improve collaboration across health and social care generally (e.g. the introduction of care coordinators in primary care networks).

Our findings extend previous research by outlining different types of responsibilities and roles needed to coordinate care for rare conditions. Previous research indicates the importance of care coordinators [12, 13, 41, 42]. However, findings extend this research by demonstrating the many different roles needed to coordinate care (administrative support, coordinators, clinical leads, GPs, charities and patients/carers). However, patient/carer involvement in coordination is not always appropriate if patients/carers are unable or do not want to coordinate their own care; and may have a negative impact on patients, families and the treatment burden that they experience [2, 12, 19, 39].

Our findings highlight the importance of following clinical guidelines and service specifications which outline how often appointments should take place. However, findings indicate that patient and provider factors need to also be taken into account when considering how often patients should be seen (see [20]).

Findings highlighted the potential for remote methods of coordination, including digital information sharing (e.g., through electronic records), virtual clinics and care coordination appointments. This shift to digital methods has been accelerated during the COVID-19 pandemic. This supports previous research, which indicates that digital methods may show some potential for use in health care delivery [43, 44]. Our findings suggest that this may also apply to care coordination, but that remote methods cannot fully replace face-to-face appointments.

Strengths and limitations

One strength of our study is that we used robust analysis procedures which strengthen the validity of this study. Twenty percent of data were coded by a second researcher. Additionally, the research team and members of the PPIAG were continually involved in discussions about analysis and findings. We also triangulated findings outputs from other parts of the CONCORD study [13, 21] to ensure no major omissions.

Whilst we sampled from a variety of rare conditions, locations and sectors, we were unable to include every rare condition. Some groups, including individuals from minority ethnic groups and certain roles (e.g. GPs) were under-represented. Therefore, whilst we collected extensive data, and included as many different views as possible, we are unlikely to have captured every possible option of care coordination. It is therefore possible that our taxonomy may not be applicable to all rare conditions, and there may be other domains or subdomains that we have not captured. However, we did speak with a range of patients, carers, professionals, commissioners and charity representatives with experience of a wide range of rare conditions and groups of rare conditions. To account for this possibility, we designed the taxonomy so that it can be applied flexibly (i.e. it is not expected that every care coordination option presented in this taxonomy would be appropriate for all rare conditions), and any application of this taxonomy should take into account a range of patient, professional, resource and societal factors that influence coordination, which will differ for all rare conditions (see [20] for factors influencing coordination and the development of hypothetical models of care coordination).

Additionally, the taxonomy was developed from data collected within the UK, and therefore it is likely that findings may only apply to the UK healthcare system. However, it is hoped that the taxonomy will also provide learnings in other healthcare contexts.

Previous research has demonstrated that one key challenge of coordination is that it is difficult to distinguish between aspects of care and coordination components [13, 45]. This is also a potential limitation of some options within our taxonomy (e.g., mode of care appointments, frequency of care appointments). However, we believe that the mode and frequency of such care appointments is part of care coordination, i.e., it may be that a care appointment that takes place virtually (with all health care professionals involved) may be more coordinated than other modes of care appointment (e.g., visiting different health care professionals for individual appointments). Additionally, this was not identified as a concern by any workshop participants.

The taxonomy is designed to cover health and social care received throughout a person’s life; however, our sample may have been limited as many of the professionals included within our study were from a medical or paramedical background. Therefore, it is possible that these findings may not account for experiences and perceptions from some social care or mental health care providers not included in this study. However, many of the patient, carer and professional findings reflected on care coordination across both health and social care, in addition to other sectors such as education.

Implications

The development of the taxonomy could lead to the standardisation of terminology for care coordination in rare conditions. Previous research proposed that better measurement of systems for organising and delivering health care systems are needed [1]. This taxonomy will help to achieve this goal as it provides a better understanding of coordination and ways of organising and delivering health care for people affected by rare conditions. This will support researchers in operationalising and measuring care coordination. If care coordination strategies are piloted, evaluated and implemented more widely within the NHS, this may lead to better care and reduced burden for people living with rare conditions [9, 46].

The taxonomy can be used by health care professionals delivering care for people with rare conditions and as a menu for policy makers, service planners, researchers and commissioners to consider when developing new and/or existing models of coordination for rare conditions. For example, we have used the taxonomy, together with the findings on the factors influencing care coordination to develop some hypothetical models of care coordination that may be applicable in different situations (see [20]). These models take into account different situations such as whether the patient would like to be involved and can coordinate their care, where the patient and carer live, whether the rare condition has a specialist centre/service, and whether it is clear which professionals need to be involved in care. This is due to the large number of rare conditions and the need to ensure that findings can be tailored appropriately to different situations. To support appropriate tailoring for individual conditions, we developed a flow chart that may inform how these taxonomy findings, together with findings on the factors influencing care coordination can be used to develop such models (see [20]). These models can be costed and evaluated by researchers and services.

These findings could be particularly helpful during the development of the rare disease action plan in response to the new Rare Disease Framework [47]; in which care coordination is identified as a key priority. The taxonomy can also be used by researchers to evaluate models of care coordination. The taxonomy also provides clinicians and patients/carers with expectations about the different ways in which care can be coordinated. Findings can be used by clinicians to map the domains of care coordination onto their current services for rare conditions, but also to consider how services may adapt or develop their services for rare conditions in future.

Given similarities between common and rare chronic conditions that were highlighted in previous research [13], researchers interested in care coordination for other conditions may be able to adapt the taxonomy for use in other complex chronic conditions. Additionally, the process outlined in this manuscript could be adapted by researchers to develop comprehensive taxonomies to understand and organise other health care services.

Future research

Future research is needed to explore where different ways of coordinating care have been implemented and to evaluate the implementation, effectiveness, and cost-effectiveness of different models of care coordination for rare conditions in practice. This is important given that it is not yet clear whether coordinated care leads to better outcomes for patients/carers, professionals and organisations. Further research is needed to operationalise care coordination models so that delivery of care coordination can be measured.

Additionally, future research on care coordination and views on care coordination from professionals working in social care, mental health and other sectors such as education may be beneficial in determining whether the taxonomy can apply in these situations or whether amendments are needed.

Conclusions

Findings from our qualitative study with key stakeholders (patients, carers, health care professionals, charity representatives and commissioners) provide a thorough taxonomy of care coordination for rare conditions. Our taxonomy can facilitate the development and evaluation of existing and new models of care coordination for people living with rare conditions. The process outlined in this manuscript provides a template that could be adapted to develop taxonomies for other health care services.

Availability of data and materials

The datasets generated and/or analysed during the current study are not publicly available due to participant confidentiality but are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

Abbreviations

- CONCORD:

-

Coordinated Care of Rare Diseases Study

- COVID-19:

-

Coronavirus Disease-19

- GP:

-

General practitioner

- HS&DR:

-

Health Services and Delivery Research Programme

- MDT:

-

Multidisciplinary Team

- NHS:

-

National Health Service

- NICE:

-

The National Institute for Health and Care Excellence

- NIHR:

-

National Institute for Health Research

- PPIAG:

-

Public Patient Involvement Advisory Group

- UCL:

-

University College London

- UK:

-

United Kingdom

References

Braithwaite J, Vincent C, Garcia-Elorrio E, et al. Transformational improvement in quality care and health systems: the next decade. BMC Med. 2020;18:340. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12916-020-01739-y.

May CR, Eton DT, Boehmer K, Gallacher K, Hunt K, MacDonald S, Mair FS, May CM, Montori VM, Richardson A, Rogers AE. Rethinking the patient: using Burden of Treatment Theory to understand the changing dynamics of illness. BMC Health Serv Res. 2014;14(1):281.

The All Party Parliamentary Group (APPG) on Rare Genetic and Undiagnosed Conditions. Leaving no one behind: why England needs an implementation plan for the UK Strategy for Rare diseases 2017. http://www.raredisease.org.uk/our-work/why-england-needs-an-implementation-plan-for-the-uk-strategy-for-rare-diseases-2017/.

Schraeder C, Shelton P. Comprehensive care coordination for chronically ill adults. Wiley-Blackwell: Chicester; 2011.

Department of Health and social care. The UK strategy for rare diseases. 2020 update to the implementation plan for England. 2020. https://www.gov.uk/government/publications/uk-strategy-for-rare-diseases-2020-update-to-the-implementation-plan-for-england.

Department of Health. The UK Strategy for Rare Diseases. 2013. https://assets.publishing.service.gov.uk/government/uploads/system/uploads/attachment_data/file/260562/UK_Strategy_for_Rare_Diseases.pdf.

Department of Health and Social care. The UK Rare Diseases Framework. 2021. https://www.gov.uk/government/publications/uk-rare-diseases-framework/the-uk-rare-diseases-framework.

NHS England. The NHS Long Term plan (v1.2). 2019. https://www.longtermplan.nhs.uk/wp-content/uploads/2019/08/nhs-long-term-plan-version-1.2.pdf.

Rare Disease UK. Understanding children and young people's experiences. 2018. http://www.raredisease.org.uk/media/3348/understanding-children-and-young-peoples-experiences-website.pdf.

Schieppati A, Henter JI, Daina E, Aperia A. Why rare diseases are an important medical and social issue. Lancet. 2008;371(9629):2039–41.

Dharssi S, Wong-Rieger D, Harold M, Terry S. Review of 11 national policies for rare diseases in the context of key patient needs. Orphanet J Rare Dis. 2017;12(1):63.

Simpson A, Bloom L, Fulop NJ, Hudson E, Leeson-Beevers K, Morris S, Ramsay AI, Sutcliffe AG, Walton H, Hunter A. How are patients with rare diseases and their carers in the UK impacted by the way care is coordinated? An exploratory qualitative interview study. Orphanet J Rare Dis. 2021;16(1):1–2.

Walton H, Hudson ME, Simpson A, Ramsay AI, Kai J, Morris S, et al. Defining coordinated care for people with rare conditions: a scoping review. Int J Integr Care. 2020. https://doi.org/10.5334/ijic.5464.

Bailey KD. Typologies and taxonomies. Thousand Oaks: SAGE; 2011. https://doi.org/10.4135/9781412986397.

Bradley EH, Curry LA, Devers KJ. Qualitative data analysis for health services research: developing taxonomy, themes, and theory. Health Serv Res. 2007;42(4):1758–72.

Valentijn PP, Boesveld IC, Van der Klauw DM, Ruwaard D, Struijs JN, Molema JJ, Bruijnzeels MA, Vrijhoef HJ. Towards a taxonomy for integrated care: a mixed-methods study. Int J Integr Care. 2015.

Porcino A, MacDougall C. The integrated taxonomy of health care: classifying both complementary and biomedical practices using a uniform classification protocol. Int J Ther Massage Bodywork. 2009;2(3):18.

Michie S, Richardson M, Johnston M, Abraham C, Francis J, Hardeman W, Eccles MP, Cane J, Wood CE. The behavior change technique taxonomy (v1) of 93 hierarchically clustered techniques: building an international consensus for the reporting of behavior change interventions. Ann Behav Med. 2013;46(1):81–95.

Tran VT, Barnes C, Montori VM, Falissard B, Ravaud P. Taxonomy of the burden of treatment: a multi-country web-based qualitative study of patients with chronic conditions. BMC Med. 2015;13(1):115.

Walton H, Simpson A, Ramsay AI, Hunter A, Jones J, Ng PL, Leeson-Beevers K, Bloom L, Kai J, Kokocinska M, Sutcliffe AG. Development of models of care coordination for rare conditions: a qualitative study. Orphanet J Rare Dis. 2022;17(1):1–24. https://doi.org/10.1186/s13023-022-02190-3.

Morris S, et al. Coordinated care of rare diseases (CONCORD): protocol for a mixed-methods study. 2018. https://fundingawards.nihr.ac.uk/award/16/116/82.

Bazzoli GJ, Shortell SM, Dubbs N, Chan C, Kralovec P. A taxonomy of health networks and systems: bringing order out of chaos. Health Serv Res. 1999;33(6):1683.

Gillies RR, Shortell SM, Anderson DA, Mitchell JB, Morgan KL. Conceptualizing and measuring integration: findings from the health systems integration study. J Healthc Manag. 1993;38(4):467.

Bogardus ST, Bradley EH, Tinetti ME. A taxonomy for goal setting in the care of persons with dementia. J Gen Intern Med. 1998;13(10):675–80.

Bradley EH, Holmboe ES, Mattera JA, Roumanis SA, Radford MJ, Krumholz HM. A qualitative study of increasing β-blocker use after myocardial infarction: Why do some hospitals succeed? JAMA. 2001;285(20):2604–11.

Ferris R, Blaum C, Kiwak E, Austin J, Esterson J, Harkless G, Oftedahl G, Parchman M, Van Ness PH, Tinetti ME. Perspectives of patients, clinicians, and health system leaders on changes needed to improve the health care and outcomes of older adults with multiple chronic conditions. J Aging Health. 2018;30(5):778–99.

Kreuger RA, Casey MA. Designing and conducting focus group interviews. St Paul, MN, 2002.

NVivo qualitative data analysis software; QSR International Pty Ltd. Version 12, 2018.

Neale J. Iterative categorization (IC): a systematic technique for analysing qualitative data. Addiction. 2016;111(6):1096–106.

Braun V, Clarke V. Using thematic analysis in psychology. Qual Res Psychol. 2006;3(2):77–101.

Nickerson RC, Varshney U, Muntermann J. A method for taxonomy development and its application in information systems. Eur J Inf Syst. 2013;22(3):336–59.

NHS England. Implementation plan for the UK strategy for rare diseases. 2018. https://www.england.nhs.uk/wp-content/uploads/2018/01/implementation-plan-uk-strategy-for-rare-diseases.pdf.

Martínez-González NA, Berchtold P, Ullman K, Busato A, Egger M. Integrated care programmes for adults with chronic conditions: a meta-review. Int J Qual Health Care. 2014;26(5):561–70. https://doi.org/10.1093/intqhc/mzu071.

McDonald KM, Sundaram V, Bravata DM, Lewis R, Lin N, Kraft SA, et al. Closing the quality gap: a critical analysis of quality improvement strategies (vol. 7, Care Coordination). 2007. 0051;04(07). https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK44015/.

Van Groenendael S, Giacovazzi L, Davison F, Holtkemper O, Huang Z, Wang Q, et al. High quality, patient centred and coordinated care for Alstrom syndrome: a model of care for an ultra-rare disease. Orphanet J Rare Dis. 2015;10(1):149. https://doi.org/10.1186/s13023-015-0366-y.

Bond M, Bowling A, Abery A, McClay M, Dickinson E. Evaluation of outreach clinics held by specialists in general practice in England. J Epidemiol Community Health. 2000;54(2):149–56.

Elrod JK, Fortenberry JL. The hub-and-spoke organization design: an avenue for serving patients well. BMC Health Serv Res. 2017;17(1):25–33.

Morris S, Ramsay AI, Boaden RJ, Hunter RM, McKevitt C, Paley L, Perry C, Rudd AG, Turner SJ, Tyrrell PJ, Wolfe CD. Impact and sustainability of centralising acute stroke services in English metropolitan areas: retrospective analysis of hospital episode statistics and stroke national audit data. BMJ. 2019.

von der Lippe C, Diesen PS, Feragen KB. Living with a rare disorder: a systematic review of the qualitative literature. Mol Genet Genomic Med. 2017;5(6):758–73.

Kane B, Luz S, O’Briain DS, McDermott R. Multidisciplinary team meetings and their impact on workflow in radiology and pathology departments. BMC Med. 2007;5(1):1.

Rare Disease UK. Rare disease care coordination. 2013. https://www.raredisease.org.uk/media/1639/rduk-care-coordinator-report.pdf.

Rare Disease UK. The rare reality—an insight into the patient and family experience of rare disease. 2016. https://www.raredisease.org.uk/media/1588/the-rare-reality-an-insight-into-the-patient-and-family-experience-of-rare-disease.pdf.

Badawy SM, Radovic A. Digital approaches to remote pediatric health care delivery during the COVID-19 pandemic: existing evidence and a call for further research. JMIR Pediatr Parent. 2020;3(1):e20049. https://doi.org/10.2196/20049.

Shaw J, Agarwal P, Desveaux L, Palma DC, Stamenova V, Jamieson T, Yang R, Bhatia RS, Bhattacharyya O. Beyond, “implementation”: digital health innovation and service design. NPJ Digital Med. 2018;1(1):1–5.

McDonald KM, Schultz E, Albin L, Pineda N, Lonhart J, et al. Care coordination measures atlas. (Prepared by Stanford University under subcontract to American Institutes for Research on Contract NO. HHSA290-2010-00005I). 2014. AHRQ Publication No. 14–0037-EF. Rockville, MD: Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality. https://www.ahrq.gov/sites/default/files/publications/files/ccm_atlas.pdf.

EURORDIS. Juggling care and daily life: the balancing act of the rare disease community. 2017. https://www.eurordis.org/publication/juggling-care-and-daily-life-balancing-act-rare-disease-community.

Department of Health & Social Care. The UK Rare Diseases Framework. 2021. https://assets.publishing.service.gov.uk/government/uploads/system/uploads/attachment_data/file/950651/the-UK-rare-diseases-framework.pdf.

Acknowledgements

Thank you to the wider CONCORD team (Professor Lyn Chitty, Sharon Parkes, and Christine Taylor) for providing support and feedback throughout the study. Thank you to the CONCORD Patient and Public Involvement Advisory Group for providing feedback throughout the project. Thank you to all of our participants who took part in the interviews, focus groups and workshops.

Funding

This study is funded by the National Institute for Health Research (NIHR) Health Services and Delivery Research programme (HS&DR Project: 16/116/82). NJF is an NIHR Senior Investigator. The views expressed are those of the authors and not necessarily those of the NIHR or the Department of Health and Social Care.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

All authors have made substantial contributions to the manuscript. All authors were responsible for the conception and design of the study: HW drafted the initial taxonomy protocol and all authors provided feedback. NJF, SM, AIGR and AH provided support and guidance throughout the project. LB and KLB helped with planning via the PPIAG. HW carried out interviews. HW, AS and EH led the focus groups. HW, EH, AIGR, SM, AH, JJ, and PLN conducted the workshops. HW, AS, and PLN organised the focus groups and workshops. HW and AS coded interview and focus group data. All authors contributed to and agreed the interpretation and analysis of the data and development of the taxonomy. HW drafted the paper and all authors contributed to the revision of the manuscript. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Ethical approval and consent to participate

This study received ethical approval from the London-Surrey Borders Research Ethics Committee of the Health Research Authority (reference: 19/LO/0250). Participants provided informed consent to participate in this study and for anonymised quotes to be published.

Consent for publication

Not applicable as all individual quotes are fully anonymised. As part of the consent to participate, all participants gave consent to their anonymised quotes being used in research publications.

Competing interests

HW, AIGR, EH, PLN, KLB, LB, JK, LK, MK, AGS, SM and NJF declare they have no competing interests. AS, AH and JJ are employees of Genetic Alliance UK. Genetic Alliance UK runs Rare Disease UK—a campaign for people with rare diseases and all who support them.

Additional information

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary Information

Additional file 1:

Topic guides for interviews and focus groups.

Additional file 2:

Topic guide for workshops.

Additional file 3:

Visual representation of workshop findings.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/. The Creative Commons Public Domain Dedication waiver (http://creativecommons.org/publicdomain/zero/1.0/) applies to the data made available in this article, unless otherwise stated in a credit line to the data.

About this article

Cite this article

Walton, H., Simpson, A., Ramsay, A.I.G. et al. Developing a taxonomy of care coordination for people living with rare conditions: a qualitative study. Orphanet J Rare Dis 17, 171 (2022). https://doi.org/10.1186/s13023-022-02321-w

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/s13023-022-02321-w