Abstract

Background

Patients and their families have become more active in healthcare systems and research. The value of patient involvement is particularly relevant in the area of rare diseases, where patients face delayed diagnoses and limited access to effective therapies due to the high level of uncertainty in market approval and reimbursement decisions. It has been suggested that patient involvement may help to reduce some of these uncertainties. This review explored existing and proposed roles for patients, families, and patient organizations at each stage of the lifecycle of therapies for rare diseases (i.e., orphan drug lifecycle).

Methods

A scoping review was conducted using methods outlined by Arksey and O’Malley. To validate the findings from the literature and identify any additional opportunities that were missed, a consultative webinar was conducted with members of the Patient and Caregiver Liaison Group of a Canadian research network.

Results

Existing and proposed opportunities for involving patients, families, and patient organizations were reported throughout the orphan drug lifecycle and fell into 12 themes: research outside of clinical trials; clinical trials; patient reported outcomes measures; patient registries and biorepositories; education; advocacy and awareness; conferences and workshops; patient care and support; patient organization development; regulatory decision-making; and reimbursement decision-making. Existing opportunities were not described in sufficient detail to allow for the level of involvement to be assessed. Additionally, no information on the impact of involvement within specific opportunities was found. Based on feedback from patients and families, documentation of existing opportunities within Canada is poor.

Conclusions

Opportunities for patient, family, and patient organization involvement exist throughout the orphan drug lifecycle. However, based on the information found, it is not possible to determine which opportunities would be most effective at each stage.

Similar content being viewed by others

Background

In recent years, patients have become active in healthcare systems and research, which have increasingly recognized the benefits of their involvement [1]. Such benefits include: improving the credibility and relevance of research [2]; enhancing the translation of research results into clinical practice; establishing more responsive services leading to better outcomes of care [3]; and identifying benefits and costs often missing from health technology assessments of new therapies [4]. While recognized by all patient communities, they are particularly valued by those with rare diseases, who experience significant challenges around their care. Often, they face delayed diagnoses and limited access to effective therapies, since decisions on market approval and reimbursement are fraught with uncertainties [5]. These uncertainties arise from a lack of robust information around 1) clinical benefit, 2) value for money, 3) potential adoption/diffusion, and 4) affordability [6]. High quality clinical trials are difficult to conduct in small patient populations where validated outcome measures are lacking [7], and natural histories are poorly understood [8, 9]. These therapies can also be extremely expensive, but in many cases, they represent the sole active treatment option for conditions that are not only rare, but also life-threatening or severely debilitating.

It has been argued that patients can play an important role in reducing decision uncertainties [10]. In Canada, the potential value of patient input is reflected in Health Canada’s draft Orphan Drug Regulatory Framework, which was originally proposed in 2012. The Framework had two objectives: 1) providing Canadians with better, timelier access to orphan drugs (i.e., drugs that treat rare diseases) and 2) encouraging and facilitating clinical research on rare diseases [5], both of which were to be accomplished, in part, by incorporating patient involvement throughout the orphan drug lifecycle (Fig. 1) [5]. However, the ways in which patients were to be involved were not specified.

Objective

The objective of this review was to explore existing and proposed roles for patients with rare diseases, their families, and patient organizations who represent them at each stage of the orphan drug lifecycle.

Methods

A scoping review was conducted using the following 6 steps developed by Arksey and O’Malley [11, 12].

Identifying the research questions

Two research questions were developed: 1) what opportunities exist for patients, families, and patient organizations to become involved at each stage of the orphan drug lifecycle, and 2) what opportunities have been proposed for involving them? In this paper, ‘patient’ refers to an individual living with a rare disease and ‘family’ refers to a patient’s family member or loved one who provides physical and emotional care.

Identifying relevant studies

Literature search

A search for relevant peer-reviewed literature published in English between January 2000 and May 2017 was conducted using the following databases: MEDLINE, PubMed, The Cochrane Library, the Centre for Reviews and Dissemination databases (DARE, NHS EED and HTA), EMBASE, Web of Science, and EconLit. Search terms included relevant controlled vocabulary (e.g., Medical Subject Headings (MeSH): Patient Preference, Patient Participation, Consumer Participation) and keywords (e.g., Patient Engagement and Patient Involvement). These were combined with terms for medical technologies (e.g., MeSH terms: Diffusion of Innovation and Biomedical Technology), as well as rare diseases (Rare Diseases and Orphan Drug Production). A search for grey literature was also conducted using ProQuest Dissertations and Theses, NHS Evidence, and Google. The electronic searches were supplemented by a manual search of reference lists of relevant papers. Full details of the search terms and sources used are provided in (see Additional file 1: Appendix A).

Review of regulatory and reimbursement decision-making processes

Over the past decade, opportunities for and public awareness of patient input into regulatory and reimbursement processes (e.g., patient evidence submissions; membership on advisory or decision-making committees) have increased considerably. To capture such opportunities, the websites of regulatory and reimbursement decision-making bodies in 20 countries were reviewed. They represented the top 20 Organization for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD) countries based on gross domestic product (GDP) per capita with populations greater than 1 million people and socialized health insurance programs/universal healthcare; thus, they were seen as relevant to the Canadian context [13]. Four countries (Qatar, Kuwait, the United Arab Emirates, and Israel) were initially included in the review, but a preliminary search revealed a paucity of information regarding decision-making processes on drugs in these countries. They were replaced with the next four OECD countries that fulfilled the inclusion criteria.

Twelve of the countries are members of the European Union (EU), which hosts the European Medicines Agency (EMA) [14]. Since it is compulsory for officially designated orphan drugs to go through EMA, its centralized regulatory approval processes were reviewed.

Searches for additional information on decision-making processes were performed using the Google search engine. When opportunities for involvement were not well described, emails were sent to the decision-making organizations to request clarification.

Study selection

Literature eligibility criteria

Literature selection was completed by two reviewers who independently scanned the titles and abstracts of citations identified through the search. Studies were included if they described the involvement of patients, families, or patient organizations in any stage of the orphan drug lifecycle. Documents produced by patient organizations describing their work were also included.

Since this review focused on involvement of patients with rare diseases, their families and patient organizations throughout the orphan drug lifecycle, literature describing “public”, “community” and “citizen” engagement, non-drug technologies, or common diseases were excluded,. However, because a broad lifecycle approach was used, literature describing activities applicable to both drug and non-drug technologies (e.g. natural history registries) was included. Papers describing patient involvement in individual clinical decision-making with health care providers were excluded, since this study focused on macro-level processes. Abstracts, editorials and commentaries were excluded.

Decision-making process eligibility criteria

No eligibility criteria were applied to the review of decision-making processes and all decision-making processes identified were included in this review.

Charting the data

One reviewer (AY) extracted data from all of the included papers using a standardized data extraction form. A second reviewer (TS) extracted data from a random sample (30%) of the included papers to assess reliability. For each ‘opportunity’ identified, the following information was extracted: description of the activity; country in which it took place; type of disease; participants involved (i.e., patients, families, or patient organizations); participants’ role; and the impact or outcome.

For each decision-making process identified, one reviewer (AY) extracted data on any aspects in which patients, families, or patient organizations were involved (e.g., submitting a topic for consideration; membership on advisory or decision-making committees). Each aspect was defined as an opportunity for involvement.

Collating, summarising and reporting the results

Thematic analysis and open coding methods were used to explore the types of activities reported in each opportunity and identify categorical themes. Thematic analysis involves the identification, analysis and reporting of patterns through repeated handling of data [15]. Open coding is used to identify themes by breaking the data into distinct parts and examining and comparing them to identify similarities and differences [16]. Where there appeared to be overlap among themes, a decision was made to keep them separate if combining them would result in the loss of an important concept or idea. For example, the theme of “Conferences and Workshops” overlaps with “Advocacy and Awareness”. While ‘advocacy’ may take place at conferences, it is not necessarily the main purpose of such events. Opportunities were also categorized as either existing (i.e., has taken place) or proposed (i.e., is suggested for the future).

Consultation exercise

Members of the Patient and Caregiver Liaison Group of a Canadian research network (Promoting Rare-Disease Innovations through Sustainable Mechanisms or PRISM [17]) were invited to participate in a webinar to validate the findings of the review and identify any additional opportunities that were missed. These individuals were either patients with rare disease patients or family members. The webinar began with a brief introduction and description of the review methodology. Subsequently, participants were presented with existing and proposed opportunities for patients, families and patient organizations (in that order) under each theme. They were invited to comment on the results and asked if they knew about any other existing or proposed opportunities. Following the webinar, participants were contacted individually for clarification or additional information as needed.

Mapping opportunities onto the orphan drug lifecycle

Opportunities for involvement were mapped onto the orphan drug lifecycle by considering the stage at which each opportunity might take place. Two maps were created, one reflecting opportunities identified in the literature/website review and the second reflecting the additional opportunities identified in the webinar.

Results

The results of the literature search and review of websites of regulatory and reimbursement processes are summarized in Appendices A and B, respectively (Additional file 1: Appendix A and Additional file 2: Appendix B). Seventy-three published studies, eleven grey literature documents, and sixty-six webpages were reviewed. Existing and proposed opportunities for involvement fell into 12 themes: research outside of clinical trials; clinical trials; patient reported outcome measures; patient registries and biorepositories; stakeholder relationships and collaborations; education; advocacy and awareness; conferences and workshops; patient care and support; patient organization development; regulatory decision-making; and reimbursement decision-making. Definitions of each theme can be found in Table C-1 (Additional file 3: Appendix C).

A summary of the most commonly identified opportunities follows.

Existing opportunities for involvement in the orphan drug lifecycle (Table 1)

Research

Individual patients and their families have contributed to strategic directions for research through membership on research priority-setting committees and participation in priority-setting exercises [18]. They have also provided input into non-clinical studies aimed primarily at understanding the experience of patients and families living with rare diseases. In contrast, roles for patient organizations have mainly involved the collection and synthesis of information from their members (e.g. evaluating the effectiveness of new orphan drugs for organization members [19]).

Clinical trials

Patient opportunities have solely comprised enrollment in clinical trials as study subjects [20]. However, patient organizations have contributed in multiple ways, including providing input into trial design and helping to recruit trial participants through communication of trial information to members [21,22,23,24].

Patient reported outcome measures

Patient reported outcome measures (PROMs) are self-reported measurement instruments designed to provide information on aspects of health status relevant to a patient’s quality of life, including symptoms, functionality, and physical, mental, and social health [25]. To date, the role of patients and families in PROMs has predominantly been in the development and validation of such measures (e.g. consulting patients when formulating questions for PROM survey [26,27,28]). Patient organizations have then managed the distribution of such surveys to patients and families [29].

Patient registries and biorepositories

Patients and families have contributed to registries (predominantly natural history) through their enrollment and submission of data [24, 30,31,32,33,34,35,36,37]. Many of the registries have been established by patient organizations, in collaboration with researchers and healthcare professionals [19, 32, 34, 37,38,39,40,41].

Stakeholder relationships and collaborations

On an individual level, patients and families have established informal relationships with researchers [35, 42]. In contrast, patient organizations have established formal relationships with stakeholders or facilitated relationships between stakeholder groups (e.g. by developing charters for collaboration [21]).

Education

Patients and families have helped develop training programs for patients/families by identifying key content areas [43, 44]. More opportunities were reported for organizations which have been involved in sharing informational resources with patients, families, and health care professionals, often through websites, toll-free hotlines, and mentoring programs [22,23,24, 40, 45,46,47]. They have also organized formal educational activities for families (e.g. parent training programs [44]) and health care professionals (e.g. Grand Rounds [22]).

Advocacy and awareness

While ‘advocacy’ by patients and families has mainly involved the use of social media to press for improved access to drugs [48], in patient organizations it has comprised a variety of efforts (e.g. lobbying for public funding; testifying before Congressional committees) spanning drug coverage [22], research [42] and legislation on rare diseases and orphan drugs [47, 49].

Conferences and workshops

Patients and families have participated in conferences and workshops (e.g. helping identify goals for a national rare disease strategy), while patient organizations have also hosted and funded them [23, 24, 34, 35, 40, 49].

Patient care and support

Some patients and families have been able to provide input into their care because they have had access and the ability to update, their electronic health records, which are reviewed by health care providers [50]. They have provided input into patient care more broadly through their participation in the development of clinical practice guidelines [51, 52].

With respect to social support, individual patients and families have built connections and shared information through online fora (e.g. Patients Like Me [53]) developed mostly by patient organizations (e.g. Muscular Dystrophy Charity [54]). Patient organizations have also provided social support through social events and mentoring programs [22, 40, 45, 49, 55].

Patient organization development

Patients and families have created patient organizations (e.g. French Muscular Dystrophy Organization [56]) which, in turn, have provided advice to others who wish to establish them [57].

Regulatory decision-making

Patients and families have mainly contributed indirectly to regulatory processes by reporting on adverse events [58,59,60,61,62,63] or providing input on proposed regulatory guidelines [64,65,66,67,68]. However, patient organizations have been more directly involved, with opportunities to serve on decision-making/advisory committees [69, 70].

Reimbursement decision-making

Opportunities for patient involvement in reimbursement decision-making have mainly focussed on patient organizations and included submission of information for use in evaluations (e.g. degree of perceived benefit, subjective risk assessment, or burden of associated side effects) [71,72,73], participation in consultations during the review process [72,73,74], and preparation of patient submissions for consideration alongside clinical and economic evidence [75,76,77]. Regarding patient submissions, similar processes exist in Australia, Canada, and the United Kingdom. In general, they involve completion of templates that ask about 1) how information in the submission was obtained, 2) impact of the disease on patients, 3) experiences of patients with their current therapy, 4) expectations patients/families for the new drug and 5) any patient experiences with the new drug [78, 79]. In Canada, the submissions also request information on family impact [78].

Opportunities for individual patients have also involved participation in safety-net programs, which provide patients with access to unapproved or non-reimbursed drugs on a case-by-case basis for a fixed time period [71, 80,81,82,83,84,85,86,87,88,89]. Individual patients and families have submitted drugs for consideration by such programs [90], participated in consultations during the review process [87], and presented their views during committee meetings [87].

Despite the wide range of existing opportunities identified, none were described in sufficient detail to determine the level of involvement they represented using published frameworks for engagement [91, 92]. These frameworks often present involvement on a spectrum, such as Arnstein’s ladder, which ranges from “manipulation” (i.e. nonparticipation) to “citizen control” (i.e. citizen power) [91]. Information on the impact of involvement in specific opportunities was also limited. One study reported, “[Patient involvement] was found to be particularly effective in enhancing the design and conduct of our research” [93]. The remaining studies typically commented on the success of an opportunity as whole (e.g. “the health utility values provided by this study could inform assessments of cost-effectiveness…” [94]).

Proposed opportunities for involvement

Proposed opportunities for involvement are presented below. In general, they were described at a high level and lacked information on the exact way in which patients, families, or patient organizations should be involved.

Research

Participants attending the Australian Rare Disease Symposium suggested that patients and their families should be directly involved in all decisions about research on rare diseases, including involvement in the decision-making processes of research collaborations and networks [95].

Clinical trials

Participants of the European Haemophilia Consortium (EHC) Congress proposed that patients should be involved in ensuring clinical trials collect real-world outcomes that are meaningful to them [96]. In the United States, the National Organization for Rare Disorders (NORD) proposed that it should develop systems for improving patient access to and participation in trials [47]. Finally, the Genetic Alliance UK proposed that patient input on acceptable risk should be embedded into R&D of new treatments, from drug design to clinical trials [97].

Stakeholder relationships and collaborations

One proposed opportunity for patients in the establishment/ maintenance of relationships with stakeholders was identified. The Genetic Alliance UK has called for improved dialogue between patients, manufacturers, regulatory bodies, and clinical researchers to ensure alignment between the data required for decision-making and the data collected in clinical trials [97].

Patient care and support

The Genetic Alliance UK proposed that patients, in partnership with their physicians, should be responsible for deciding if the benefits of using a new drug outweigh the associated risks [97]. Families participating in a research study proposed that those who have taken part in clinical trials provide support for newly enrolled patients and families [98].

Regulatory decision-making

Three organizations proposed opportunities for involvement in regulatory decision-making. In the United Kingdom, the Genetic Alliance UK suggested that patient input on acceptable risk should be incorporated into decision-making [97]. In Europe, participants in the EHC Congress symposium proposed that patient representatives should be added to advisory committees that do not currently have representation [96]. In the United States, NORD proposed that it should be involved in 1) identifying laws, regulations and policies that need to be changed to encourage product approval [47] and 2) establishing greater certainty in the orphan product approval process, through consultations on trial design and endpoint selection [47].

Reimbursement decision-making

At the EHC Congress’s Symposium, it was suggested that patient input should be sought at an earlier stage in the health technology assessment (HTA) process [96] and that patient advocates and clinicians should work together to create a shared consensus on the evaluation of the efficacy and effectiveness of therapies [96]. In the United Kingdom, the Genetic Alliance UK proposed four potential roles for patient involvement in reimbursement decision-making: presenting to the evaluation committee, consulting on the development of post-evaluation research, providing input on any reassessment of risks and benefits, and contributing to topic selection during horizon scanning [97]. The Genetic Alliance UK also stated that patient organizations should be formally involved in drug identification and selection for reimbursement decision-making [97]. In the United States, NORD proposed that patient organizations work to assure reimbursement of off-label drug use for rare disease patients [47].

Consultation exercise (feedback from patients and families)

Eight members of the PRISM Patient and Caregiver Liaison Group participated in a webinar, during which feedback on the above existing and proposed opportunities was sought. Members represented a variety of disease types (e.g. cancer; non-cancerous tumor; blood, metabolic; connective tissue; endocrine; lung; secretory gland; and epileptic encephalopathies) and a range of experience within their disease communities. Five participants were patients and three were family members. All eight were involved in patient organizations to some degree (from new members to holding executive positions). This allowed participants to speak from their perspective as patients/family members and members of patient organizations. Participants ranged in age from 18 to 70 years and there were two males and six females. The session lasted 2.5 h. In general, participants agreed with the findings of the review, but identified some opportunities that were not captured in the literature. They also clarified their role in some of the opportunities that were identified. These additions and clarifications are described below.

Research

Patients and families have fundraised for research, even when there is no organization to represent them. Patients, specifically, have also provided input on the format in which they would like to receive a new drug, should it come to market (e.g., pill vs. liquid).

Clinical trials

Patients and families differentiated between recruiting patients to clinical trials and providing them with enough information to make informed decisions on whether or not to participate. They felt that while they had a role to play in “providing all the information necessary so… patients know what options are out there in terms of research” (Family member 2 (FM2)), it did not include recruitment of participants.

Patient registries and biorepositories

Patients and families mentioned their involvement in raising funds to establish registries (without the support of an organization) and using social media (e.g., Facebook) to encourage enrollment. They also discussed some of the challenges they have experienced, such as cost:

“…you’ve listed ‘establish and maintain registries’ but a lot of organizations do not do that because it is too expensive, too onerous.” – FM2.

To address these challenges, organizations are considering different types of registries, some of which involve partnerships with industry or the academic community. They have encouraged their members to participate in registries established by industry and requested data from these registries to share with the disease community.

Stakeholder relationships and collaborations

Patients and families indicated that some have been very proactive about building relationships with stakeholders outside of a patient organization, (individuals “can be the link between stakeholders” (Patient 4 (P4)) (e.g., linking fundraisers with patient organizations). They provided examples of their own relationships with the government through their local Members of Parliament (MPs) and Members of the Legislative Assembly (MLAs).

Education

Patients and families discussed a variety of work they have done “as individual[s]… not through the patient organization” (FM1) to provide education about their disease to, not only other patients and families, but also health care professionals. They have presented at Grand Rounds in academic medical centres and participated in standardized patient programs at universities, which has helped to familiarize students in health-related fields with different a range of rare medical conditions.

Advocacy and awareness

Patients and families believe “…there’s a time and place for both [patients and patient organizations] to come in and [do advocacy]…individual patients have done a lot of individual advocacy work.” (P3). They have advocated for access to new drugs well before social media existed (e.g., meeting with their local MPs) and for improved education, clinics, and patient care services. They have also taken part in campaigns hosted by research organizations, initiated their own campaigns (online and in schools), and hosted fundraising events.

With respect to patient organizations, they have provided guidance to patients and families around how to advocate for themselves, linked them with resources in their community and written letters of support.

Conferences and workshops

Patients and families indicated that at conferences and workshops, “…you have the expert patients who can share their knowledge and give their perspective to other patients or even to doctors and healthcare providers” (P4). One participant had served on a planning committee and organized opportunities for patient involvement (e.g., sitting on a panel) to ensure that these opportunities were driven by actual patients. Another participant had volunteered at patient organization-hosted conferences, aiming to help the conference run more smoothly and increase involvement by assisting with aspects such as childcare.

Patient care and support

Patients and families felt that, as individuals, they provide not “not just social support” (FM3), but also clinical care support, helping other patients to identify appropriate treatments and dosing. Patient organizations also offer clinical care support through sharing information on treatments and services available locally in each province/territory.

Regulatory decision-making

Participants mentioned that they had participated in a webinar hosted by Health Canada, which described its plans to “include patient involvement in regulatory decision-making”. However, they “didn’t think it had gotten very far on it…” (P3). No additional information on this project was found.

Reimbursement decision-making

Participants described their own experiences with patient evidence submissions to the common drug review (CDR) in Canada. Many felt that the weight given to patient submissions during decision-making, compared with other sources of information (e.g., clinical trial data) was unclear.

“…I know very little about the weight it’s given. I don’t think anybody knows the weight it’s given” – FM2.

Participants also described ways in which patient organizations have been involved in decision-making when the CDR issues a negative recommendation. These included media campaigns and meetings with government officials in several provinces.

Other

Participants discussed the importance of sharing information on specific ways in which they have been involved at the different stages of the orphan drug lifecycle:

“…the patients and families who are involved in that have to be ambassadors and get out there and show the rest of the research community how it works and how it was successful and what the impact was…we’re trying to change a whole culture of how researchers think and work…if they can get concrete examples of how it’s worked in the past and how it’s been successful and how it’s enhanced the research, they may be more open to just having it proposed to them...” – P3.

This was seen as particularly important when patient involvement was non-traditional (e.g. development of equal partnerships with researchers conducting trials).

Mapping opportunities onto the orphan drug lifecycle

Opportunities for patients, families, and patient organizations mapped onto the orphan drug lifecycle are presented in Table D-1 (Additional file 4: Appendix D). The 12 themes were then mapped onto the lifecycle in Figures D-1 to D-3 (Additional file 4). These figures demonstrate that opportunities for patients, families, and patient organizations exist throughout the lifecycle. In fact, nine of the themes or categories of opportunities spanned the entire lifecycle. They also illustrate gaps in the literature that were subsequently filled through the webinar. Notably, almost none of the gaps related to opportunities for patient organizations.

Discussion

Through the literature review, an inventory of existing and proposed opportunities for patients, families, and patient organizations at each stage of the orphan drug lifecycle was compiled. Further opportunities were identified by webinar participants, demonstrating the need for greater information-sharing of examples of patient and family involvement in Canada. Members of the rare disease community have been engaged in a variety of roles throughout the lifecycle of drugs for these diseases. However, there has not been a standardized approach to their engagement. As well, based on the literature the effects of this engagement on drug development, approval, or funding are unclear, since no evaluations have been done. Patients, families, and patient organizations have also proposed additional and increased roles for them in the lifecycle, suggesting that they feel current levels of involvement are inadequate. However, again, there is no framework proposed for a more consistent and meaningful engagement.

This situation does not appear to be unique to rare diseases. While no similar inventory of involvement opportunities for patients with common diseases could be found, it has been acknowledged that, in general, efforts need to be made to increase patient engagement in the research, development, and approval of new drugs [99, 100]. For all diseases, developing a drug that will improve patients’ lives requires a deep understanding of their medical condition, including their needs, preferences, and the trade-offs they are willing to make. These insights can be gained through improved patient involvement, leading to more relevant and impactful patient outcomes and make drug development faster, more efficient, and more productive. To this end, researchers have worked to develop frameworks for patient involvement in research [101,102,103] and the pharmaceutical industry has proposed the development of a “master framework” for integrated and systematic patient involvement [99]. However, there are differences between common diseases and rare diseases and it is reasonable to expect that the need for and best approach to patient involvement may differ between them. Given the nature of rare diseases (i.e. low prevalence; disease heterogeneity), clinical investigators often have less exposure to and understanding of the disease and its progression. As a result, there is a greater chance of failing to capture what is important to patients. While this inventory may have some relevant learnings for common diseases, it was compiled with a focus on rare diseases and the specific challenges associated with developing orphan drugs. With these challenges in mind, the National Center for Advancing Translational Sciences recently released their Toolkit for Patient-Focused Therapy Development. Launched in September 2017, the toolkit provides online resources to patient organizations intended to help them advance medical research on their disease (e.g. how to establish a patient registry; how to conduct post-market surveillance) [104].

This study has several limitations. The published papers, grey literature, and websites reviewed were limited to English only. Additionally, with the exception of the assessment of regulatory and reimbursement decision-making processes, the results were limited to papers describing opportunities for rare disease patients only. Therefore, some opportunities may have been missed. Finally, only one webinar was held, and it involved members of a patient liaison group within a research collaborative. Although actively engaged in Canada’s rare diseases community for many years, they may not have been familiar with all opportunities for involvement.

Conclusion

There are a number of opportunities, both existing and proposed, for patients, their families, and the organizations representing them to become involved in the orphan drug lifecycle. However, based on the information found, it is not possible to determine which opportunities would be most effective at each stage of the lifecycle.

Abbreviations

- CDR:

-

Common Drug Review

- EHC:

-

European Haemophilia Consortium

- GDP:

-

Gross Domestic Product

- MeSH:

-

Medical Subject Headings

- MLA:

-

Member of the Legislative Assembly

- MP:

-

Member of Parliament

- NORD:

-

National Organization for Rare Disorders

- OECD:

-

Organization for Economic Co-operation and Development

- PRISM:

-

Promoting Rare-Disease Innovations through Sustainable Mechanisms

- PRO:

-

Patient Reported Outcome

- PROM:

-

Patient Reported Outcome Measure

References

Douglas C, Wilcox E, Burgess M, Lynd L. Why orphan drug coverage reimbursement decision-making needs patient and public involvement. Health Policy. 2015;119:588–96.

Esmail L, Moore E, Rein A. Evaluating patient and stakeholder engagement in research: moving from theory to practice. J Comp Effect Res. 2015;4:133-45.

Barello S, Graffigna G, Vegni E. Patient engagement as an emerging challenge for healthcare services: mapping the literature. Nurs Res Practice. 2012; doi:10.1155/2012/905934.

Report on Innovating Health: Public Engagement in Health Technology Assessments and Coverage Decisions. In: Canada's Public Policy Forum. 2011. http://www.ppforum.ca/sites/default/files/Innovating_Health_Final_Report_0.pdf. Accessed 9 Nov 2015.

Lee D, Wong B. An orphan drug framework (ODF) for Canada. J Popul Ther Clin Pharmacol. 2014;21:e42–6.

Morel T, Arickx F, Befrits G, Siviero P, Van Der Meijden C, Xoxi E, et al. Reconciling uncertainty of costs and outcomes with the need for access to orphan medicinal products: a comparative study of managed entry agreements across seven European countries. Orphanet J Rare Dis. 2013;8:198.

Meekings KN, Williams CS, Arrowsmith JE. Orphan drug development: an economically viable strategy for biopharma R&D. Drug Discov Today. 2012;17:660–4.

Dunoyer M. Accelerating access to treatments for rare diseases. Nat Rev Drug Discov. 2011;10:475–6.

Institute of Medicine Committee on Accelerating Rare Disease Research and Orphan Product Development. Rare diseases and orphan products: accelerating Research and Development. 1st ed. Washington: The National Academies Press; 2010.

Menon D, Stafinski T, Dunn A, Short H. Involving patients in reducing decision uncertainties around orphan and ultra-orphan drugs: a rare opportunity? Patient. 2014;8:29–39.

Arksey H, O'Malley L. Scoping studies: towards a methodological framework. Int J Soc Res Methodol. 2005;8:19–32.

Levac D, Colquhoun H, O'Brien K. Scoping studies: advancing the methodology. Implement Sci. 2010;5:69.

GDP per capita (current US$). [https://data.worldbank.org/indicator/NY.GDP.PCAP.CD]. Accessed 21 July 2015.

Central authorisation of medicines. [http://www.ema.europa.eu/ema/index.jsp?curl=pages/about_us/general/general_content_000109.jsp&mid=WC0b01ac0580028a47]. Accessed 21 July 2015.

Savin-Baden M, Howell Major C. Qualiative Research: The essential guide to theory and practice. 1st ed. Abingdon: Routledge; 2013.

Saldana J. The coding manual for qualitative researchers. 2nd ed. London: SAGE; 2013.

PRISM: Promoting Rare-Disease Innovations through Sustainable Mechanisms. [http://www.prismfive.org/]. Accessed: 6 Sept 2016.

Mavris M, Le CY. Involvement of patient organisations in research and development of orphan drugs for rare diseases in Europe. Mol Syndromol. 2012;3:237–43.

Ferguson T. Key concepts in online health: e-patients as medical researchers. [http://www.fergusonreport.com/articles/fr00903.htm]. Accessed 6 Sept 2016.

Patient Involvement in Clinical Research: A guide for sponsors and investigators. In: Genetic Alliance UK. 2016. https://www.geneticalliance.org.uk/media/1603/patientpartnersponsor.pdf. Accessed 21 July 2015.

Eurordis Charter for collaboration between sponsors and patient organisations for clinical trials in rare diseases. In: EURORDIS. 2011. http://www.eurordis.org/IMG/pdf/Charter_Clinical_Trials-Final.pdf. Accessed 31 May 2014.

Black AP, Baker M. The impact of parent advocacy groups, the internet, and social networking on rare diseases: the IDEA league and IDEA league United Kingdom example. Epilepsia. 2011;52(Suppl 2):102–4.

Groft SC, Gopal-Srivastava R. A model for collaborative clinical research in rare diseases: experience from the rare disease clinical research network program. Clin Invest. 2013;3:1015–21.

Seminara J, Tuchman M, Krivitzky L, Krischer J, Lee HS, Lemons C, et al. Establishing a consortium for the study of rare diseases: the urea cycle disorders consortium. Mol Genet Metab. 2010;100(Suppl 1):S97–105.

About SMC: Membership. [http://www.scottishmedicines.org.uk/About_SMC/Who_we_are/Membership/Membership]. Accessed 31 May 2014.

Wicks P, Massagli MP, Wolf C, Heywood J. Measuring function in advanced ALS: validation of ALSFRS-EX extension items. Eur J Neurol. 2009;16:353–9.

Abdulla S, Vielhaber S, Korener S, Machts J, Heinze HJ, Dengler R, et al. Validation of the German version of the extended ALS functional rating scale as a patient-reported outcome measure. J Neurol. 2013;260:2242–55.

Hoffman HM, Wolfe F, Belomestnov P, Mellis SJ. Cryopyrin-associated periodic syndromes: development of a patient-reported outcomes instrument to assess the pattern and severity of clinical disease activity. Curr Med Res Opin. 2008;24:2531–43.

Kodra Y, Morosini PR, Petrigliano R, Agazio E, Salerno P, Taruscio D. Access to and quality of health and social care for rare diseases: patients' and caregivers' experiences. Ann Ig. 2007;19:153–60.

Montano AM, Tomatsu S, Gottesman GS, Smith M, Orii T. International Morquio A Registry: clinical manifestation and natural course of Morquio a disease. J Inherit Metab Dis. 2007;30:165–74.

Pastores GM, Arn P, Beck M, Clarke JT, Guffon N, Kaplan P, et al. The MPS I registry: design, methodology, and early findings of a global disease registry for monitoring patients with Mucopolysaccharidosis type I. Mol Genet Metab. 2007;91:37–47.

van der Meijden JC, Gungor D, Kruijshaar ME, Muir AD, Broekgaarden HA, van der Ploeg AT. Ten years of the international Pompe survey: patient reported outcomes as a reliable tool for studying treated and untreated children and adults with non-classic Pompe disease. J Inherit Metab Dis. 2014;38(3):495–503.

Mallbris L, Nordenfelt P, Bjorkander J, Lindfors A, Werner S, Wahlgren CF. The establishment and utility of Sweha-Reg: a Swedish population-based registry to understand hereditary angioedema. BMC Dermatol. 2007;7:6.

Cystic Fibrosis Foundation patient registry: annual data report. In: Cystic Fibrosis Foundation. 2012. http://www.cysticfibrosisdata.org/LiteratureRetrieve.aspx?ID=149756. Accessed 31 May 2014.

de Blieck EA, Augustine EF, Marshall FJ, Adams H, Cialone J, Dure L, et al. Methodology of clinical research in rare diseases: development of a research program in juvenile neuronal ceroid lipofuscinosis (JNCL) via creation of a patient registry and collaboration with patient advocates. Contemp Clin Trials. 2013;35:48–54.

Richesson RL, Lee HS, Cuthbertson D, Lloyd J, Young K, Krischer JP. An automated communication system in a contact registry for persons with rare diseases: scalable tools for identifying and recruiting clinical research participants. Contemp Clin Trials. 2009;30:55–62.

Wang RT, Nelson SF. What can Duchenne connect teach us about treating Duchenne muscular dystrophy? Curr Opin Neurol. 2017;28:535–41.

TREAT-NMD: serving the neuromuscular community. In: TREAT-NMD. 2014. http://www.treat-nmd.eu/downloads/file/brochure/treat_nmd_brochuremay2010.pdf. Accessed 31 May 2014.

Schwartz ME, Zimmerman GM, Smith F, Sprecher E. Pachyonychia Congenita project: a partnership of patient and medical professional. J Dermatol Nurses Assoc. 2013;5:42–7.

About the VHL Alliance (VHLA). [https://www.vhl.org/about/]. Accessed 31 May 2014.

Workman TA. Engaging patients in information sharing and data collection: the role of patient-powered registries and research networks. Rockville: US Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality (AHRQ); 2013.

Caron-Flinterman JF, Broerse JE, Bunders JF. The experiential knowledge of patients: a new resource for biomedical research? Soc Sci Med. 2005;60:2575–84.

Badiu C, Bonomi M, Borshchevsky I, Cools M, Craen M, Ghervan C, et al. Developing and evaluating rare disease educational materials co-created by expert clinicians and patients: the paradigm of congenital hypogonadotropic hypogonadism. Orphanet J Rare Dis. 2017;12:57.

Kodra Y, Kondili LA, Ferraroni A, Serra MA, Caretto F, Ricci MA, et al. Parent training education program: a pilot study, involving families of children with Prader-Willi syndrome. Ann Ist Super Sanita. 2016;52:428–33.

Scarpa M, Almassy Z, Beck M, Bodamer O, Bruce IA, De ML, et al. Mucopolysaccharidosis type II: European recommendations for the diagnosis and multidisciplinary management of a rare disease. Orphanet J Rare Dis. 2011;6:72.

Boon W, Broekgaarden R. The role of patient advocacy organisations in neuromuscular disease R&D--the case of the Dutch neuromuscular disease association VSN. Neuromuscul Disord. 2010;20:148–51.

Dunkle M, Pines W, Saltonstall PL. Advocacy groups and their role in rare diseases research. In: Posada de la Paz M, Groft SC, editors. Rare diseases epidemiology. Dordrecht: Springer; 2010. p. 515–525.

Goodman M. Twitter storm forces Chimerix's hand in compassionate use request. Nat Biotechnol. 2014;32:503–4.

Lasker JN, Sogolow ED, Sharim RR. The role of an online community for people with a rare disease: content analysis of messages posted on a primary biliary cirrhosis mailinglist. J Med Internet Res. 2005;7:e10.

Pattacini C, Rivolta GF, Di PC, Riccardi F, Tagliaferri A. Haemophilia Centres network of Emilia-Romagna region. A web-based clinical record 'xl'Emofilia' for outpatients with haemophilia and allied disorders in the region of Emilia-Romagna: features and pilot use. Haemophilia. 2009;15:150–8.

Pai M, Santesso N, Yeung CH, Lane SJ, Schunemann HJ, Iorio A. Methodology for the development of the NHF-McMaster guideline on care models for Haemophilia management. Haemophilia. 2016;22:17–22.

Lane SJ, Sholapur NS, Yeung CHT, Iorio A, Heddle M, Sholzberg M, et al. Understanding stakeholder important outcomes and perceptions of equity, acceptability and feasibility of a care model for haemophilia management in the US: a qualitative study. Haemophilia. 2016;22:23–30.

Frost JH, Massagli MP, Wicks P, Heywood J. How the social web supports patient experimentation with a new therapy: the demand for patient-controlled and patient-centered informatics. AMIA Annu Symp Proc. 2008;2008:217–21.

Patient participate! Case study report. In: The British Library. 2011. http://blogs.ukoln.ac.uk/patientsparticipate/files/2011/10/Case-study-report-Final.pdf. Accessed 31 May 2014.

Landy DC, Brinich MA, Colten ME, Horn EJ, Terry SF, Sharp RR. How disease advocacy organizations participate in clinical research: a survey of genetic organizations. Genet Med. 2012;14:223–8.

Rabeharisoa V. The struggle against neuromuscular diseases in France and the emergence of the "partnership model" of patient organisation. Soc Sci Med. 2003;57:2127–36.

Mai PL, Malkin D, Garber JE, Schiffman JD, Weitzel JN, Strong LC, et al. Li-Fraumeni syndrome: report of a clinical research workshop and creation of a research consortium. Cancer Gene Ther. 2012;205:479–87.

Reporting problems. [http://www.tga.gov.au/consumers/problem.htm#.U5XIPnJdWAh]. Accessed 31 May 2014.

Adverse Reaction and Medical Device Problem Reporting. [https://www.canada.ca/en/health-canada/services/drugs-health-products/medeffect-canada/adverse-reaction-reporting.html#a1]. Accessed 18 Sept 2015.

Bere N. Lifecycle of a new medicinal product - with emphasis on pharmacovigilance. In: European Medicines Agency (EMA) 2013. http://www.ema.europa.eu/docs/en_GB/document_library/Presentation/2013/01/WC500137842.pdf. Accessed 31 May 2014.

Safety information: how to report a problem. [http://www.medsafe.govt.nz/safety/report-a-problem.asp]. Accessed 31 May 2014.

Pharmacovigilance. [https://www.swissmedic.ch/swissmedic/en/home/humanarzneimittel/marktueberwachung/pharmacovigilance.html]. Accessed 31 May 2015.

Reporting serious problems to FDA. [http://www.fda.gov/Safety/MedWatch/HowToReport/]. Accessed 31 May 2014.

About Health Canada: Advisory Committees. [http://www.hc-sc.gc.ca/ahc-asc/branch-dirgen/hpfb-dgpsa/ocpi-bpcp/eac-cce/index-eng.php#a6]. Accessed 30 May 2015.

Drug and Health Products: Expert Advisory Committee on the Vigilance of Health Products. [http://publications.gc.ca/collections/collection_2011/sc-hc/H164-137-2011-eng.pdf]. Accessed 30 May 2015.

Medicines Classification Committee - public consultation on agenda items. [http://www.medsafe.govt.nz/profs/class/ClassificationSubmissionsForReclassification.asp]. Accessed 31 May 2014.

About the Patient Representative Program. [https://www.fda.gov/ForPatients/About/ucm412709.htm]. Accessed 30 May 2015.

Advisory Committees. [http://www.fda.gov/AdvisoryCommittees/]. Accessed: 30 May 2015.

Fifth report on the interaction with patients' and consumers' organisations. In: European Medicines Agency. 2011. http://www.ema.europa.eu/docs/en_GB/document_library/Report/2012/10/WC500133475.pdf. Accessed 30 May 2015.

Committees, working parties, and other groups. [http://www.ema.europa.eu/ema/index.jsp?curl=pages/about_us/general/general_content_000217.jsp&mid=]. Accessed 30 May 2015.

Franken M, le Polain M, Cleemput I, Koopmanschap M. Similarities and differences between five European drug reimbursement systems. Int J Technol Assess Health Care. 2012;28:349–57.

Getting Involved in PHARMAC Decision-Making. In: Pharmaceutical Management Agency (PHARMAC). 2015. http://www.pharmac.health.nz/assets/factsheet-13-getting-involved-in-pharmac-decision-making.pdf. Accessed 31 May 2015.

Factors CMS Considers in Referring Topics to the Medicare Evidence Development & Coverage Advisory Committee. [https://www.cms.gov/medicare-coverage-database/details/medicare-coverage-document-details.aspx?MCDId=10]. Accessed 10 June 2016.

Winquist E, Coyle D, Clarke JT, Evans GA, Seager C, Chan W, et al. Application of a policy framework for the public funding of drugs for rare diseases. J Gen Intern Med. 2014;29(Suppl 3):774–9.

Guidelines for preparing submissions to the Pharmaceutical Benefits Advisory Committee. [http://www.pbac.pbs.gov.au/home.html]. Accessed 30 May 2015.

Guide to the process of technology appraisal. [https://www.nice.org.uk/article/pmg19/chapter/3-The-appraisal-process]. Accessed 31 May 2015.

New Medicines Group (NMG). [http://www.awmsg.org/nmg_about_us.html]. Accessed 31 May 2015.

Patient Input Templates. [https://www.cadth.ca/about-cadth/what-we-do/products-services/cdr/patient-input]. Accessed 13 June 2016.

Obtaining consumer comments on submissions to the Pharmaceutical Benefits Advisory Committee meetings. [http://www.pbs.gov.au/info/industry/listing/elements/pbac-meetings/pbac-consumer-comments]. Accessed 31 May 2014.

Life Saving Drugs Program Criteria and Conditions. [http://www.health.gov.au/internet/main/publishing.nsf/Content/lsdp-criteria]. Accessed 22 September 2015.

Section 100 – Highly Specialised Drugs Program. [http://www.pbs.gov.au/info/browse/section-100/s100-highly-specialised-drugs]. Accessed 22 September 2015.

Reimbursement. [http://sundhedsstyrelsen.dk/da/medicin/tilskud]. Accessed 22 September 2015.

Temporary authorisations for use (ATU). [http://agence-tst.ansm.sante.fr/html/pdf/5/atu_eng.pdf]. Accessed 31 May 2014.

Ordinance on the placing on the market of unauthorised medicinal products for compassionate use (Ordinance on Medicinal Products for Compassionate Use - AMHV). In: Bundesministerium fur Gesundheit / German Federal Minister of Health. 2010. https://www.bfarm.de/SharedDocs/Downloads/EN/Drugs/licensing/clinicalTrials/compUse/AMHV_en.pdf?__blob=publicationFile&v=3. Accessed 31 May 2014.

Kavanagh C, Diamond D, O'Gorman M: Ireland. In: Arthur Cox. 2014. http://www.arthurcox.com/wp-content/uploads/2014/01/European-Lawyer-Reference-2013-Guide-to-the-Distribution-and-Marketing-of-Drugs8478574_1.pdf. Accessed 31 May 2014.

Exceptional Circumstances. [https://www.pharmac.health.nz/tools-resources/forms/exceptional-circumstances/]. Accessed 24 Sept 2015.

Process for advising on the feasibility of implementing a patient access scheme. Interim. In: National Institute for Health and Care Excellence (NICE). 2009. https://www.nice.org.uk/Media/Default/About/what-we-do/PASLU/PASLU-process-guide.pdf. Accessed 31 May 2014.

Patient Access Schemes. [https://www.scottishmedicines.org.uk/Submission_Process/Submission_guidance_and_forms/Patient-Access-Schemes]. Accessed 22 Sept 2015.

Wales Patient Access Scheme. [http://www.awmsg.org/healthcare_wpas.html]. Accessed 22 Sept 2015.

Application for basic reimbursement status and reasonable wholesale price. [http://www.hila.fi/en/applying-and-notifications/forms-and-instructions;jsessionid=3f1ea0e8efd9320c068e055342be]. Accessed 23 Sept 2015.

Arnstein SR. A Ladder of citizen participation. J Am Inst Plann. 1969;35:216–24.

Carman KL, Dardess P, Maurer M, Sofaer S, Adams K, Bechtel C, et al. Patient and family engagement: a framework for understanding the elements and developing interventions and policies. Health Aff. 2013;32:223–31.

Serrano-Aguilar P, Trujillo-Martin MM, Ramos-Goni JM, Mahtani-Chugani V, Perestelo-Perez L, Posada-de la Paz M. Patient involvement in health research: a contribution to a systematic review on the effectiveness of treatments for degenerative ataxias. Soc Sci Med. 2009;69:920–5.

Swinburn P, Wang J, Chandiwana D, Mansoor W, Lloyd A. Elicitation of health state utilities in neuroendocrine tumours. J Med Econ. 2012;15:681–7.

Molster C, Youngs L, Hammond E, Dawkins H. Key outcomes from stakeholder workshops at a symposium to inform the development of an Australian national plan for rare diseases. Orphanet J Rare Dis. 2012;7:50.

O'Mahony B, Kent A, Ayme S. Pfizer-sponsored satellite symposium at the European Haemophilia consortium (EHC) congress: changing the policy landscape: haemophilia patient involvement in healthcare decision-making. Eur J Haematol Suppl. 2014;74:1–8.

Patient perspectives and priorities on NICE's evaluation of highly specialised technologies: patient charter. In: Genetic Alliance UK. 2014. https://www.geneticalliance.org.uk/media/1850/hst-patient-charter_final.pdf. Accessed 30 May 2015.

Bendixen RM, Morgenroth LP, Clinard KL. Engaging participants in rare disease research: a qualitative study of Duchenne muscular dystrophy. Clin Ther. 2016;38:1474–84.

Hoos A, Anderson J, Boutin M, Dewulf L, Geissler J, Johnston G, et al. Partnering with patients in the development and lifecycle of medicines: a call for action. Ther Innov Regul Sci. 2015;49:929–39.

Lowe M, Blaser D, Cone L, Arcona S, Ko J, Sasane R, et al. Increasing patient involvement in drug development. Value Health. 2016;19:869–78.

Shippee N, Domecq JP, Prutsky Lopez GJ, Wang Z, Elraiyah TA, Nabhan M, et al. Patient and service user engagement in research: a systematic review and synthesized framework. Health Expect. 2013;18:1151–66.

Domecq JP, Prutsky G, Elraiyah T, Wang Z, Nabhan M, Shippee N, et al. Patient engagement in research: a systematic review. BMC Health Serv Res. 2014;14:89.

Kirwan JR, de Wit M, Frank L, Haywood KL, Salek S, Brace-McDonnell S, et al. Emerging guidelines for patient engagement in research. Value Health. 2017;20:481–6.

Toolkit for patient-focused therapy development. [https://rarediseases.info.nih.gov/toolkit]. Accessed 2 Dec 2017.

Henrard S, Speybroeck N, Hermans C. Participation of people with haemophilia in clinical trials of new treatments: an investigation of patients' motivations and existing barriers. Blood Transfus. 2015;13:302–9.

Consolaro A, Morgan EM, Giancane G, Rosina S, Lanni S, Ravelli A. Information technology in paediatric rheumatology. Clin Exp Rheumatol. 2016;34:S11–6.

Khodyakov D, Kinnett K, Grant S, Lucas A, Martin A, Denger B, et al. Engaging patients and caregivers managing rare dsieases to improve the methods of clinical guideline development: a research protocol. JMIR Res Protoc. 2017;6:e57.

Khodyakov D, Grant S, Meeker D, Booth M, Pacheco-Santivanez N, Kim KK. Comparative analysis of stakeholder experiences with an online approach to prioritizing patient-centered research topics. J Am Med Inform Assoc. 2017;24:537–43.

Merkel PA, Manion M, Gopal-Srivastava R, Groft S, Jinnah HA, Robertson D, et al. The partnership of patient advocacy groups and clinical investigators in the rare diseases clinical research network. Orphanet J Rare Dis. 2016;11:66.

Mattsson M, Bostrom C, Mihai C, Stocker J, Geyh S, Stummvoll G, et al. Personal factors in systemtic sclerosis and their coverage by patient-reported outcome measures. A multicentre European qualitative study and literature review. Eur J Phys Rehabil Med. 2017;51:405–21.

Patient involvement pilot for orphan drugs launches in Canada. [http://www.thepharmaletter.com/article/patient-involvement-pilot-for-orphan-drugs-launches-in-canada]. Accessed 31 May 2015.

Sussex J, Rollet P, Garau M, Schmitt C, Kent A, Hutchings A. A pilot study of multicriteria decision analysis for valuing orphan medicines. Value Health. 2013;16:1163–9.

Annual Health, Labour and Welfare Report 2010-2011: Health and Medical Services. [http://www.mhlw.go.jp/english/wp/wp-hw5/02.html]. Accessed 30 May 2015.

Medicines Assessment Advisory Committee. [http://www.medsafe.govt.nz/committees/maac.asp]. Accessed 30 May 2015.

Keng Ho P. Regulatory and reimbursement decision-making in Singapore. Personal. Communication. 19 May 2015;

Medicines Adviosry Committee. [http://www.hsa.gov.sg/content/hsa/en/About_HSA/Advisory_Committees/Medicines_Advisory_Committee.html]. Accessed 30 May 2015.

Report Adverse Events related to Health Products. [http://www.hsa.gov.sg/content/hsa/en/Health_Products_Regulation/Safety_Information_and_Product_Recalls/Report_Adverse_Events_related_to_health_products.html]. Accessed 22 September 2015.

Reglement der Swissmedic Medicines Expert Committees (SMEC). [file:///C:/Users/aldunn/Downloads/ZL003_00_002d_SD_SMEC_Reglement.pdf]. Accessed 30 May 2015.

About FDA: FAQs about CDER. [http://www.fda.gov/AboutFDA/CentersOffices/OfficeofMedicalProductsandTobacco/CDER/FAQsaboutCDER/default.htm#1]. Accessed 30 May 2015.

Bakowska M, Berekmeri-Varro R, Biro H, Brandt S, Bruyndonckx A, Casanueva A. Pricing and reimbursement handbook 2011. [http://docplayer.net/18937797-Pricing-andreimbursement-handbook.html]. Accessed 10 June 2014.

Buchholz P: ISPOR Global Health Care Systems Road Map: Austria - Pharmaceuticals. [ http://www.ispor.org/htaroadmaps/austria.asp]. Accessed 31 May 2015.

Picavet E, Cassiman D, Simoens S. Reimbursement of orphan drugs in Belgium: what (else) matters? Orphanet J Rare Dis. 2014;9:139.

Government Decree on the Pharmaceuticals Pricing Board. In: Ministry of Social Affairs and Health. 2009. http://stm.fi/en/article/-/asset_publisher/legislati-3. Accessed 31 May 2015.

Rochaix L, Xerri B. National authority for health: France. Issue Brief (Commonw Fund) 2009; 58: 1–9.

Transparency Committee. [http://www.has-sante.fr/portail/jcms/c_1729421/en/transparency-committee]. Accessed 31 May 2015.

The subcommittees. [http://www.english.g-ba.de/structure/subcommittees/]. Accessed 31 May 2015.

Federal Joint Committee: Members. [http://www.english.g-ba.de/structure/members/]. Accessed 31 May 2015.

LeIP Report. Lymphoma Coalition. [http://www.lymphomacoalition.org/147-global-information/229-global-report]. Accessed 31 May 2015.

About PHARMAC. [http://www.pharmac.health.nz/about]. Accessed 31 May 2015.

PHIS Pharma profile: Norway. In: Pharmaceutical Health Information System (PHIS). 2011. https://phis.goeg.at/downloads/library/PHIS%20Pharma%20Profile%20Norway%20Nov11.pdf. Accessed 31 May 2014.

About SMC: What we do. [http://www.scottishmedicines.org.uk/About_SMC/What_we_do/index]. Accessed 30 May 2015.

Bedgood R, Sadurski R, Schade RR. The use of the internet in data assimilation in rare diseases. Dig Dis Sci. 2007;52:307–12.

Syed AM, Camp R, Mischorr-Boch C, Houyez F, Aro AR. Policy recommendations for rare disease centres of expertise. Eval Program Plann. 2015;52:78–84.

Coathup V, Teare HJ, Minari J, Yoshizawa G, Kaye J, Takahashi MP, et al. Using digital technologies to engage with medical research: views of myotonic dystrophy patients in Japan. BMC Med Ethics. 2016;17:51.

Morel T, Ayme S, Cassiman D, Simoens S, Morgan M, Vandebroek M. Quantifying benefit-risk preferences for new medicines in rare disease patients and caregivers. Orphanet J Rare Dis. 2016;11:70.

Carroll R, Antigua J, Taichman D, Palevsky H, Forfia P, Kawut S, et al. Motivations of patients with pulmonary arterial hypertension to participate in randomized clinical trials. Clin Trials. 2012;9:348–57.

Nierse CJ, Abma TA, Horemans AM, van Engelen BG. Research priorities of patients with neuromuscular disease. Disabil Rehabil. 2013;35:405–12.

van Merode T, Bours S, van Steenkiste B, Sijbers T, van der Hoek G, Vos C, et al. Describing patients' needs in the context of research priorities in patients with multiple myeloma or Waldenstrom's disease: a truly patient-driven study. Z Evid Fortbild Qual Gesundhwes. 2016;112:11–8.

Johnson J, Adams-Spink G, Arndt T, Wijeratne D, Heyhoe J. Providing family-centered care for rare diseases in maternity services: parent satisfaction and preferences when dysmelia is identified. Women Birth. 2016;29:e99–e104.

Doyle M. Peer support and mentorship in a US rare disease community: findings from the Cystinosis in emerging adulthood study. Patient. 2015;8:65–73.

Tosi LL, Oetgen ME, Floor MK, Huber MB, Kennelly AM, McCarter RJ, et al. Initial report of the osteogenesis imperfecta adult natural history initiative. Orphanet J Rare Dis. 2015;10:146.

McCormack P, Woods S, Aartsma-Rus A, Hagger L, Herczegfalvi A, Heslop E, et al. Guidance in social and ethical issues related to clinical, diagnostic care and novel therapies for hereditary neuromuscular rare diseases: "translating" the translational. PLoS Curr. 2013;5

Fleurence RL, Beal AC, Sheridan SE, Johnson LB, Selby JV. Patient-powered research networks aim to improve patient care and health research. Health Aff. 2014;33:1212–9.

Ekins S, Clark AM, Williams AJ. Open drug discovery teams: a chemistry mobile app for collaboration. Mol Inform. 2012;31:585–97.

Panofsky A. Generating sociability to drive science: patient advocacy organizations and genetics research. Soc Stud Sci. 2011;41:31–57.

de Moerloose P, Arnberg D, O'Mahony B, Colvin B. Improving haemophilia patient care through sharing best practice. Eur J Haematol. 2015;95:1–8.

Duchange N, Darquy S, d'Audiffret D, Callies I, Lapointe AS, Loeve B, et al. Ethical management in the constitution of a European database for leukodystrophies rare diseases. Eur J Paediatr Neurol. 2014;18(5):597–603.

Therapeutics Development Network. [https://www.cff.org/Research/Researcher-Resources/Therapeutics-Development-Network/]. Accessed 30 May 2015.

Kelly J. Environmental scan of cystic fibrosis research worldwide. J Cyst Fibros. 2017;16:367–70.

Fajac I, Bulteel V, Castellani C, Lee T, Derichs N, Drevinek P, et al. The European cystic fibrosis society-clinical trials network: an international network to optimize clinical research for a rare disease. Clin Invest. 2013;3:921–6.

Dell SD, Leigh MW, Lucas JS, Ferkol TW, Knowles MR, Alpern A, et al. Primary ciliary dyskinesia: first health-related quality-of-life measures for pediatric patients. Ann Am Thorac Soc. 2016;13:1726–35.

Evangelista T, Wood L, Fernandez-Torron R, Williams M, Smith D, Lunt P, et al. Design, set-up and utility of the UK facioscapulohumeral muscular dystrophy patient registry. J Neurol. 2016;263:1401–8.

Lochmuller H, Ayme S, Pampinella F, Melegh B, Kuhn KA, Antonarakis SE, et al. The role of biobanking in rare diseases: European consensus expert group report. Biopreserv Biobank. 2009;7:2009.

Rubinstein YR, Groft SC, Bartek R, Brown K, Christensen RA, Collier E, et al. Creating a global rare disease patient registry linked to a rare diseases biorepository database: rare disease-HUB (RD-HUB). Contemp Clin Trials. 2010;31:394–404.

Rubinstein YR, Groft SC, Chandros SH, Kaneshiro J, Karp B, Lockhart NC, et al. Informed consent process for patient participation in rare disease registries linked to biorepositories. Contemp Clin Trials. 2012;33:5–11.

Woodward L, Johnson S, Vande Walle J, Beck J, Gasteyger C, Licht C, et al. An innovative and collaborative partnership between patients with rare disease and industry-supported registries: the global aHUS registry. Orphanet J Rare Dis. 2017;11:154.

Baldo C, Casareto L, Renieri A, Merla G, Garavaglia B, Goldwurm S, et al. The alliance between genetic biobanks and patient organizations: the experience of the telethon network of genetic biobanks. Orphanet J Rare Dis. 2016;11:142.

Hughes L. One in a million: navigating health information and advocacy in rare disease diagnosis and treatment. Fairfax: George Mason University; 2013.

The patient's voice in the evaluation of medicines: how patients can contribute to assessment of benefit and risk. In: European Medicines Agency (EMA). 2013. http://www.ema.europa.eu/docs/en_GB/document_library/Report/2013/10/WC500153276.pdf. Accessed 31 May 2014.

INTANZA Intradermal 9μg Dose Influenza Vaccine for persons 18-59 years of age: data sheet. In: SANOFI. 2013. http://products.sanofi.com.au/vaccines/INTANZA_9mcg_NZ_PI_2013-03.pdf. Accessed 13 Dec 2017.

For Patients. [https://www.fda.gov/ForPatients/default.htm]. Accessed 13 Dec 2017.

FDA working with patients to explore benefit/risk: opportunities & challenges. [http://www.fda.gov/ForPatients/About/ucm412666.htm]. Accessed 31 May 2014.

New Funding Applications. [https://www.pharmac.health.nz/medicines/how-medicines-are-funded/new-funding-applications/]. Accessed 31 May 2015.

The pCODR Expert Review Committee (pERC). [https://www.cadth.ca/collaboration-and-outreach/advisory-bodies/pcodr-expert-review-committee-perc]. Accessed 31 May 2015.

Medicare dCoverage Information Exchange: Public Comments. [https://www.cms.gov/Medicare/Coverage/InfoExchange/publiccomments.html]. Accessed 31 May 2015.

Horizon Scanning Centre. Progress Report on Patient and Public Involvement & Engagement 2012–2014. Birmingham: National Institute for Health Research Horizon Scanning Centre (NIHR HSC); 2015.

Angrist J, Lavy V, Schlosser A. Multiple experiments for the causal link between the quantity and quality of children. J Labor Econ. 2010;28:773–823.

Guidelines for Intiation of Stakeholder Meetings. [http://www.pbs.gov.au/info/industry/listing/elements/initiation-of-stakeholder-meetings]. Accessed 30 May 2015.

The Federal Joint Committee - About Us. In: The Federal Joint Committee (G-BA). 2015. http://www.english.g-ba.de/downloads/17-98-2804/2010-01-01-Faltblatt-GBA_engl.pdf. Accessed 31 May 2015.

PACE (Patient & Clinician Engagement) Overview Document. In: Scottish Medicines Consortium. 2014. http://www.scottishmedicines.org.uk/files/new_medicines_review/PACE_Overview_Document_May_2014.pdf. Accessed 31 May 2015.

The Pharmaceutical Benefits Board - areas of responsibility and tasks. In: The Dental and Pharmaceutical Benefits Agency (TLV). 2015. http://www.tlv.se/Upload/English/ENG-lfn-responsibility-tasks.pdf. Accessed 31 May 2015.

Muller KR. [http://www.ispor.org/htaroadmaps/switzerlandph.asp#Diagram]. Accessed 31 May 2015.

Technology Appraisal Committee. [http://www.nice.org.uk/Get-Involved/Meetings-in-public/Technology-Appraisal-Committee]. Accessed 31 May 2015.

Medicare Evidence Development & Coverage Advisory Committee. [https://www.cms.gov/Regulations-and-Guidance/Guidance/FACA/MEDCAC.html]. Accessed 10 June 2016.

Canadian Drug Expert Committee (CDEC). [https://www.cadth.ca/canadian-drug-expert-committee-cdec]. Accessed 31 May 2015.

NICE technology appraisal guidance. [https://www.nice.org.uk/About/What-we-do/Our-Programmes/NICE-guidance/NICE-technology-appraisal-guidance]. Accessed 31 May 2015.

Public Involvement: Submission form and guidance. [http://www.scottishmedicines.org.uk/Public_Involvement/Submission_form_and_guidance]. Accessed 30 May 2015.

Lopes E, Carter D, Street J. Power relations and contrasting conceptions of evidence in patient-involvement processes used to inform health funding decisions in Australia. Soc Sci Med. 2015;135:84–91.

Acknowledgements

The authors would like to thank Leigh-Ann Topfer and Lynne Lacombe for their assistance during the literature search phase of this review, as well as the PRISM Patient and Caregiver Liaison Group for their invaluable feedback provided in the consultation exercise.

Funding

This study was supported by funding from the Canadian Institutes of Health Research Emerging Team Grant (TR3119194).

Availability of data and materials

The datasets analyzed during the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request, pending consent from participating patients and families.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

AY made substantial contributions to the conception and design of this study, analysis and interpretation of the data, critical revision, and final approval of the manuscript. DM made substantial contributions to the conception and design of this study, analysis and interpretation of the data, critical revision, and final approval of the manuscript. JS made substantial contributions to the analysis and interpretation of the data, critical revision, and final approval of the manuscript. WA-H made substantial contributions to the analysis and interpretation of the data, to critical revision, and to final approval of the manuscript. TS made substantial contributions to the conception and design of this study, analysis and interpretation of the data, critical revision, and final approval of the manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate

This study received ethics approval from the University of Alberta Research Ethics Board, Project Name "Patient Preferences around Therapies for Rare Disease", no. MS1_Pro00029603, September 3, 2014. Informed consent was obtained from all patients and families participating in the consultation exercise.

Consent for publication

Consent for publication was obtained from all patients and families participating in the consultation exercise.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Additional files

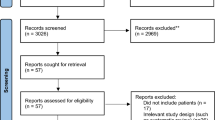

Additional file 1:

Appendix A includes full details of the search terms and sources used in the literature search, the PRISMA diagram, and a detailed tabulation of the literature search results. (DOCX 297 kb)

Additional file 3:

Appendix C contains definitions of the themes identified. (DOCX 34 kb)

Additional file 4:

Appendix D contains figures depicting the identified opportunities for patients, families, and patient organizations mapped onto the orphan drug lifecycle. (DOCX 147 kb)

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/), which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made. The Creative Commons Public Domain Dedication waiver (http://creativecommons.org/publicdomain/zero/1.0/) applies to the data made available in this article, unless otherwise stated.

About this article

Cite this article

Young, A., Menon, D., Street, J. et al. Exploring patient and family involvement in the lifecycle of an orphan drug: a scoping review. Orphanet J Rare Dis 12, 188 (2017). https://doi.org/10.1186/s13023-017-0738-6

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/s13023-017-0738-6