Abstract

Background

Intensification of agricultural systems may result in overexploitation of water resources in arid regions because enhanced productivity of crops is often associated with increased actual evapotranspiration (AET). The aim of this study was to quantify the effect of increased regional AET on the groundwater level in a case study of the oasis located within the Shiyang River Basin near the edge of the Gobi Desert.

Result

The results of the study show that regional AET increased during the period from 1981 to 2010 due to increasing oasis area and air temperature. The water losses due to AET exceeded the water supply from the mountainous discharges of the basin by the end of this period, leading to groundwater overexploitation in the oasis area.

Conclusions

This case study shows the importance of considering the effect of climate change on water losses associated with increasing agricultural production for the sustainable agricultural development of arid regions.

Similar content being viewed by others

Background

Anthropogenic modifications have had substantial influences on natural earth systems in past centuries. For example agricultural development has led to a significant impact on water-soil exploitation [1], resulting in remarkable variations in regional ecohydrology and the availability of water resources in many parts of the world [2,3,4,5,6]. Today, human beings are facing a series of water-related challenges, including the need to meet growing requirements for food production, human health, environmental safety, and so on [7, 8]. The inherent requirement of water resources for socioeconomic development, especially in arid or semiarid regions, has caused river exploitation to reach capacity [9], resulting in deterioration of the river systems and groundwater systems [10,11,12], as well as degradation of land surface ecology [13, 14]. Specifically, inland river basins in northwestern China have experienced prosperous periods over the past thousands of years when the availability of water was adequate for a limited amount of agriculture and grazing [15]. The balance of supply and demand in many natural-artificial water systems in this region has sharply tipped in recent decades due to rapid population growth and oasis scale expansion [16, 17]. The original nature of river-groundwater exchange in the middle and lower parts of the basins was changed by division/storage projects and groundwater pumping. Artificial procedures have greatly altered the natural horizontally dominated slower water movement [18] into vertically dominated faster processes in irrigated areas [19, 20]. Water availability could not match the speed of consumption. Stresses of continuously increasing utilization have inevitably resulted in general water overexploitation in critically water-scarce areas [21,22,23].

From the perspective of water balance in inland river basins, mountainous discharge maintains the existence of natural oases, artificial oases and groundwater systems [24, 25]. On the one hand, due to the arid climate and intensive evapotranspiration, rare precipitation cannot form locally effective recharge for the groundwater system in the plain area of the inland river basin [26]. On the other hand, desert vegetation is significantly affected by local precipitation, while oasis water consumption for vegetative productivity is mainly supported by mountainous discharge and groundwater [27]. With the continuous expansion of the oasis scale and the increasing consumption of water for industrial and life purposes, water resources from mountains have gradually become insufficient, and local areas have to exploit groundwater to meet the increasing water requirements [28]. Based the above information, surface runoff development leads to a decrease in supplies, and groundwater abstraction reduces reserves, both of which contribute to rapid groundwater system degradation [29].

Quantification of the ecological-environmental processes that involve water in arid regions is essential for understanding and planning local development. However, errors in data collection regarding water utilization may result in significant uncertainties in analyses. Fortunately, land surface processes, such as variation in greenness and AET monitored by satellite sensors, as well as their derivations, satisfactorily represent reality [30], e.g., classification of land use/cover types in a satellite image could be a key to determining hydrological variables, such as AET, for evaluation of anthropogenic modification impacts on complex hydrological processes [31,32,33]. In addition, fine-temporal imagery products, such as the NDVI (normalized difference vegetation index) from Advanced Very High Resolution Radiometer (AVHRR) or Moderate Resolution Imaging Spectroradiometer (MODIS) sensors have provided potential long-term land cover change interpretations [34,35,36], which is also an important widely used indicator for studying the carbon–water balance in the context of climate change and plays a key role in water management [37,38,39,40,41].

Given the high-level complexity of multifactor interactions in natural-artificial water systems [42], the hydrological responses to climate and human impacts across a whole basin are difficult to quantifiably predict. In particular, the quantification of the relationship between the groundwater system and oasis scale [43] in arid inland river basins has rarely been reported. In this study, a 30-year data package was prepared, which includes hydrometeorology, remotely sensed NDVI, GLEAM-AET and other data. The objective of the study was to analyze oasis changes during the 1981 to 2010 period, determine oasis vegetation water consumption using GLEAM-AET data combined with surveys of water utilization in life and industrial systems, calculate oasis water consumption and water deficit, and then assess groundwater abstraction and its effectiveness in the regional groundwater system. The study could help residents better understand the artificial impacts on arid hydrological processes and benefit water planning and watershed management in arid regions under the background of climate change.

Method

Study area

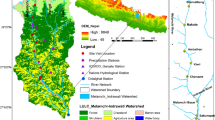

The Shiyang River Basin (SYRB) is located in the easternmost part of the Hexi Corridor, which is mainly formed by 7 upstream rivers sourced from Qilian Mountain (southwestern area shown in Fig. 1). The Shiyang River flows north and passes Hongya Mountain, flowing into the Minqin district in the lower reaches. The flow generation area is located in the alpine zones with elevations ranging from 5130 to 1855 m, and this area is dominated by lower Paleozoic epimetamorphic rocks and intensively cutting river networks. Groundwater is mainly fissure vein and interlayer water, which discharges into the river channels, flowing out of the mountainous outlets and into the middle and lower reaches where the elevation ranges between 1855 and 1260 m, from the northernmost part of the southern mountains to the edge of the northern desert. Channel river water infiltrates and percolates into the deep Quaternary alluvial fans and deep underground from 100 m to more than 200 m in the south slope area of the mountains, overflowing at the edge of the fans as springs and accumulating again in the land surface rivers; finally, this water cuts through the northern mountain valleys and partially becomes groundwater in the lacustrine deposit system. The remaining water forms ephemeral rump lakes and is eventually consumed by evapotranspiration, maintaining the regional water balance in the area [44]. Land covers show significant spatial heterogeneity, with distinct vertical zonation across the basin. The hydrological conditions in the area are representative of inland river basins [45].

Location map and oasis distribution in the SYRB. The basin is divided into upper, middle and lower reach areas according to regional hydrogeomorphology. The oases are mainly located in the latter two reach areas, which north of the Hongya Reservoir are considered to be in the lower reaches (administratively part of the Minqin district), and others are considered to be in the middle reaches (administratively part of the Wuwei, Jingchang and Yongchang districts)

At present, there are nearly 2.4 million people in the SYRB, and the population density is over 600 people per km2 in the oasis area. The amount of water required to match socioeconomic development in the area has dramatically increased since the early 1980s in conjunction with the extension of arable land. The irrigated area in the 1970s was approximately 0.25 million ha, which expanded to over 0.4 million ha from the 1980s to 2010s. The large demand for agricultural irrigation has increased the use of mountainous discharge and groundwater abstraction. The overexploitation of water resources has strained the regional developmental capacity for a relatively long time [46], resulting in a series of hydrological consequences, including considerable drawdown of groundwater [47]. Land surface ecology has deteriorated due to the groundwater system decline; most xerophytic shrubs, such as elaeagnus angustifolia and white spines, have died out. As desertification increased, native farmers were forced to migrate out of the area as “environmental refugees” [16].

Data collection and processing

Hydrometeorological data were collected in or near the SYRB, including data from 10 national weather stations (China meteorological data sharing network, http://cdc.cma.gov.cn) and seven hydrological observational stations (Gansu Province Bureau of Hydrology and Water Resources Monitoring) at the outlets of the mountainous sub-basins. The double-mass curve method [48] was used to check consistency for each hydrometeorological factor. The analogy method (linear) was adopted to interpolate or extend the missing data to complete the full 30-year series from 1981 to 2010. Actual evapotranspiration (AET) data were sourced from GLEAM (Global Land Evaporation Amsterdam Model, http://www.gleam.eu) datasets with a spatial resolution of 0.25°, which have been verified to agree well with land surface flux observations in China [49,50,51]. Especially in arid northwestern China, which has few observation stations, GLEAM-AET can help to obtain spatially and temporally better regional AET [52, 53]. Compared with other AET products (e.g., MOD16, JRA, GLDAS), GLEAM-AET has higher spatial and temporal resolutions (0.25°, 1 day) and matches better with data requirements in basin-scale studies. The spatial distribution of different AET products was similar to some extent, although the expression of high values of MOD16 AET was too large [54], and the seasonal volatility of GLDAS AET was relatively high, especially in spring [55]. Monthly GLEAM-AET data collected over a year was accumulated into the annual GLEAM-AET from 1981 to 2010. All AET data are resampled to a 250 m resolution to maintain consistency with other data. We collected well-monitored groundwater data from administrative units, including the Gansu Province Bureau of Hydrology and Water Resources Monitoring, Gansu Province Geology Survey, and Gansu Province Environmental Protection Agency. Data from the 129 monitoring wells were mainly distributed in the oasis area. Data for the local socioeconomy and the related water utilization were sourced from official statistics. The NDVI data required for the study were derived from the AVHRR, 8 km resolution, 1981 to 2006, https://ecocast.arc.nasa.gov/) and the MODIS, 250 m resolution, 2001 to 2010, http://glovis.usgs.gov/). The land use/cover map used as the basis for calibration and validation of land cover classification was obtained from China’s National Land Cover Dataset (NLCD 2000, http://www.resdc.cn/).

NDVI data cross-calibration

The AVHRR and MODIS NDVI products were used for determination of the maximum pixel NDVI value by the maximum-value composite (MVC) method in this study. All of the remotely sensed data were resampled into 250 m × 250 m images to keep the spatial resolution identical. Next, series consistency was assessed and cross-calibrated by correlating corresponding pixels during the overlapping time period from 2001 to 2006 [34]. A linear regression method implemented for the overlapping time period was used to assimilate the two series for the extension of data to the full time series from 1981 to 2010. The regressive equation for cross-calibration was found in the following linear form:

The consistency of the two NDVI series was verified, with a correlation coefficient of 0.79 (P ≤ 0.05). The assimilated NDVI dataset could be considered satisfactory for series extension, and the data resolution was treated at the same level as the MODIS data.

Variation statistics

The spatiotemporal variations in the key factors are analyzed using zonal statistics and Sen’s slope method [56]. Sen’s slope is a widely used method for variation analyses of hydrological and meteorological series. Judgment is based on the median of the series of slopes. When evaluating the variation trend and amplitude of the time series, the Sen’s slope method can reduce or avoid the impact of data anomalies and omissions. The formula is outlined as follows:

where Senij is Sen’s slope; and Xi and Xj represent the sequential values corresponding to times i and j, respectively, where 1 < i < j < n, n is the length of the series.

Determination of oasis extent

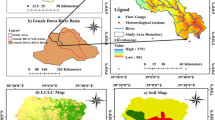

The area of the oasis was determined by coupling thresholds from the remotely sensed NDVI value and DTM datasets. Thresholds of vegetation greenness (NDVI value), altitude (DEM) and slope (derived from DEM) were defined according to the AOI (Area of Interest) training samples corresponding to the land cover types illustrated in an NLCD map. The above thresholds were used to determine the yearly extent of the oasis in the plain area of the SYRB.

Analysis of the AOIs resulted in thresholds of altitude ≤ 2200 m and slope ≤ 7°, corresponding to locations of arable oases that were mainly distributed in plain areas, reflecting that significant cultivation occurred in the relatively flat area with lower altitude in the SYRB. The annual maximum NDVI value based on the MVC method was trained into ≥ 0.4 in these areas, including small areas of forest and grassland with high land coverage supported by irrigation, near water bodies or in areas with shallow groundwater burial. Other land cover types, such as sparse vegetation (arid or semiarid shrubs or grassland) and bare land (desert or Gobi), were excluded because the focus of this study is mainly on artificial water utilization and its effectiveness in groundwater systems.

Regressive module of AET

The driving mechanism of oasis AET was explored based on regressions by setting areal averages of air temperature (T), precipitation (P) and the NDVI values as independent variables under a multi-linear module at the monthly time scale. For reasonable regression fittings, AIC (Akaike information criterion) values [57] were calculated step by step under different parameter settings to assess the reliability of the model’s capacity and parameter selection. The data used to interpret the influencing mechanism of the AET dynamics is the GLEAM-AET product, which is considered to be the observed AET series. During the process of the stepwise regression, we used the whole time series (1981–2010) for exploration of the driven module:

where \(b_{i}\) is the regression coefficient for the key climatic or vegetative index (\(C_{i}\)) and \({\upvarepsilon}\) is a constant term.

Groundwater dynamics

Flooding irrigation in the study area dominated infiltration and percolation through the soil layer to the phreatic system. We assume that the recharged groundwater part would finally provide abstraction and contribute to AET consumption in the oasis area. Thus, groundwater utilization could be generally illustrated by a simple water balance module under a “net” framework (Eq. 4). Precipitation is excluded because it is rarely able to recharge groundwater systems in arid regions where precipitation is within 100–200 mm/a [47, 58, 59]:

where \({\text{GW}}_{\text{U}}\) is the annually positive/negative balance of the groundwater (108 m3);\({\text{A}}_{\text{O}}\) is the area of the oasis (104 ha); \({\text{V}}_{\text{LI}}\) is the surveyed water consumption for life and industrial purposes (108 m3); and \({\text{V}}_{\text{D}}\) is the division of mountainous discharge (Fig. 2) that supports oasis water utilization (108 m3, which could be determined by surveying water division works at the mountain outlets and the Hongya Reservoir, which provides water to the lower area of the basin). Number 1000 is the arithmetic operator.

We consider the groundwater dynamics to be a holistic consequence influenced by land surface and underground water supply and utilization (Fig. 2). Thus, considering the observations of mountainous discharges, surveyed life and industrial water utilization and the simulated/monitored AET and \({\text{A}}_{\text{O}}\), the relationships between groundwater level dynamics and other factors could be further explored using the following regressive formation:

where \(\Delta {\text{G}}_{\text{W}}\) is the accumulative dynamics of the groundwater level according to the regional average of well monitoring.

Results

Oasis scale from 1981 to 2010

The scale of the oasis continued to increase during the period. Surveys and our analysis both pointed to a significant extension of the irrigated oasis scale during the 1980s (Fig. 3). The oasis area increased from 24.5 × 104 ha to nearly 40 × 104 ha over the ten-year period. Subsequently, the increase in oasis area became slighter than previously. In the late 2000s, a small shrinkage was found in the middle reaches, which occupied approximately 77% of the total oasis area of the basin.

Correlation between AET and climatic and vegetative factors

Changes in the key variables

Statistics of the monthly variation in the 30-year span resulted in different changeable amplitudes for all 4 variables (Fig. 4). Generally, warming facilitated aridity in arid areas because of sparse precipitation, although artificial irrigation changed the water supply and supported vegetation growth. Greenness reflected by NDVI presented suppression in most of the initial growing stages, regardless of whether the precipitation increased or decreased. The AET increased along with the upward air temperature in each stage (Fig. 4, columns 3–4), reflecting the facilitation of warming on the regional AET. Most crops in the study area turned into developing/middle stages from May to July. Statistics showed in an obvious decrease in precipitation but a remarkable increase in AET in June (Fig. 4, column 6). Given the small amount of rainfall, irrigation played an important role in this stage. Additionally, less precipitation may correspond to more sunny days, verifying the increasing AET requirement at this stage. Similarly, increased rainfall (more cloudy days), combined with the decrease in air temperature in September, suppressed AET to some extent, although the greenness (NDVI) strengthened (Fig. 4, column 9). This indicates that except for vegetative transpiration, environmental loss through soil evaporation was necessary to support the total AET water consumption.

Regressive module of AET

For a better understanding of AET variation under the background of climate change and human activities in the oasis area, the growing season GLEAM-AET (mainly during the time period from March to November in the area) was regressed in a stepwise manner using the key factors of T, P and NDVI, as illustrated in Eq. (3). Zonal statistics were used to calculate values of the four factors at a monthly time scale. We used the forward stepwise regression method to input factors and compared the AIC values. The AICs decreased to 994.93, 970.48, and 954.79 as the number of parameters increased from 1 to 3, respectively, indicating that the effectiveness of the selected model and variables in AET simulation is reliable. Regressions showed positive influences of T and NDVI but a negative influence of P on regional AET variations. The final module by stepwise regression was calibrated as follows:

where AET represents the simulated AET in the oasis area when key climatic factors and the vegetative index are considered to be auxiliary variables, T is the average monthly air temperature (°C), P is the monthly total precipitation (mm), and NDVI is the MVC-based monthly NDVI.

The stepwise regression was fitted with satisfactory precision, and the correlation coefficient was 0.87 when compared with the GLEAM-AET. (Figure 5), meaning that the regressive module could explain approximately 87% of the GLEAM-AET.

Relationship between AET and the influential factors

Module applications and statistics revealed that during the 1981 to 2010 period, the air temperature increased by 1.74 °C, facilitating an increase in AET by 56.2 mm (approximately 32.3 mm/ °C). The increase in precipitation during the growing season over the 30-year period was summed to 41.7 mm, with an approximately 6.7 mm suppression of AET (an approximate ratio of − 1.6 mm/10 mm). The oasis scale presented extension according to remote sensing monitoring, and the NDVI value averaged into a total increase of 0.12, resulting in an AET of an additional 13.7 mm (an approximate ratio of 11.4 mm corresponding to the strengthened unit greenness of 0.1). The above aggregated findings pointed to unit influences of 32.3 mm/ °C, − 1.6 mm/10 mm and 11.4 mm/0.1 in the changeable T, P and NDVI, respectively, on oasis AET variations in the SYRB (Fig. 9b). Consequently, the contribution ratios of climate change (varied T and P) and oasis ecology (mainly supported by irrigation) to the changed AET were calculated to be 78% and 22%, respectively, at the 30-year time scale. Although artificial irrigation basically supported the oasis ecology, it was warming that dominated the increase in the consumptive oasis AET in arid regions, as in the SYRB, given a growing vegetation condition of adequate water supply.

Net water consumption in the oasis area of the SYRB

Net oasis water consumption was determined by the product of GLEAM-AET and the remote sensing-based delineation of the oasis scale. Spatial statistics resulted in average AET consumptions of 359.97 mm/a and 442.46 mm/a, corresponding to total oasis water utilizations of 11.04 × 108 m3 and 3.89 × 108 m3 in the middle and lower reaches, respectively. Combined with household and industry water consumption, averaged as 1.96 × 108 m3 and 0.17 × 108 m3 in the middle and lower oases during the reference period, respectively, the net water consumption in the oasis area of the SYRB was 17.06 × 108 m3, although multi-yearly monitored mountainous discharges were averaged as a total volume of 13.99 × 108 m3 over the 30-year period. When considering possible water loss through evaporation in rivers, wetlands and reservoirs, the total water demand far exceeded the available water resources in the SYRB.

Responses of the groundwater system to oasis water utilization

Net consumption of groundwater

Due to the large water requirement in the oasis area, water utilization has continuously increased in China’s inland river basins in recent decades. At the basin level, the gross supply of water resources consists of two parts: the water amounts extracted from mountainous discharges and groundwater abstractions. According to our statistics, the reservoir-canal systems extracted almost all mountainous discharges for oasis water utilization in the middle and lower reaches, which provided approximately 82% of the total oasis water consumption; the remainder was mainly supported by local groundwater abstraction.

A series of simulated oasis AET and remote sensing monitored oasis scale data, combined with monitored or surveyed mountainous discharges and life and industrial water use, were input as parameters into Eq. (4) to determine the net balance of the groundwater system (\({\text{GW}}_{\text{U}}\)). Groundwater levels from monitoring wells (Fig. 1) were treated as differential series to illustrate the dynamics, which were spatially averaged to represent the regional responses corresponding to net groundwater consumption. Collaborative trends of the two accumulative series in both the middle and lower reaches (Fig. 6) indicated that quantification under a net balance module was reliable for estimating the influences of oasis water utilization on the groundwater system. Obvious differences in groundwater utilization and responses were found in the middle and lower reaches. More net consumption of groundwater led to near-linear and greater drawdown of the groundwater level in the lower reaches, while that in the middle oasis area fluctuated occasionally as a result of the large percolation recharge from channel transfer and irrigation. Consequently, before 1995, there was an overall positive groundwater balance in the middle part of the basin, and the total water consumption in the area was less than the mountainous discharge provided. Conversely, there was continual drawdown in the lower oasis area over the whole period, indicating a continuously negative balance in the groundwater system there. Considering water sources, the relatively smaller drawdown of the groundwater level in the area of the middle reaches benefitted from the advantages of the mountainous discharge, while the obviously severe decline in the underground water system in the lower reaches was mainly because of the finite water division into the Hongya Reservoir and the intensive abstraction.

Relationship between groundwater dynamics and influential factors

Accumulative series of the variables in Eq. (5) were stepwise regressed to calibrate the key factors affecting the groundwater dynamics. Life and industrial water (VLI) was considered to be one of the potential factors influencing groundwater dynamics in the equation. This value increased from 0.9 × 108 to 3.29 × 108 from 1981 to 2010, although the proportions were still small (only 7–17% to the annual total, Fig. 7). VLI was excluded during the regressive exploration for the relatively small fitting contributions, meaning that the groundwater dynamics were not synergetic or significant to the increase in life and industrial water use, and key factors influencing regional groundwater dynamics were mountainous discharge and oasis ecological water utilization.

Stepwise regression resulted in the following expression:

The regression revealed that the main factors influencing groundwater variation were oasis AET, oasis scale and water diversion by different kinds of water conservancy projects. The regression coefficient was calibrated to an R2 of 0.89 (Fig. 8), indicating that the relationship between the four variables (dependent variable was the monitored groundwater dynamics) was essential. A negative value indicates an increase in the groundwater level, generally corresponding to slight dynamics (points in the ellipse). Equation (7) is considered to express the relationship among the four variables with satisfactory reliability at a regional level.

Ideal oasis scale for a sustainable groundwater system

Under the framework illustrated in Eq. (7), the combination of irrigation area and oasis AET impacted the groundwater level drawdown, while the diversion of land surface water could counteract and retard the decline in the groundwater system. Given the neglect of local interactions between the land surface and underground water system (e.g., temporary exchanges of water in some of the river sections, local depressions due to intensive abstractions, evaporation in water bodies) and the induced errors in quantifying the relationships, the scenario of no groundwater drawdown could aid in further exploring the rational or ideal oasis water utilization under the background of human regulation and climate change. Figure 9 was plotted in correspondence to different surface water divisions under the hypothesis of no groundwater level drawdown, which could also aid in understanding oasis water utilization when considering groundwater system recovery. Ellipses present ranges of oasis AET and scale from 1981 to 2010 in the SYRB. Triangles indicate the average of the variables, while the crosses represent the ideally rational oasis area supported by the real land surface water diversion without groundwater drawdown. During the time period from 1981 to 2010, observations and simulations revealed numerical ranges of oasis AET (334–396, in mm) and oasis scale (18.4–45.0, in 104 ha) in the middle reaches, while those in the lower reaches were in the ranges of 408–483, in mm and 4.5–11.1, in 104 ha for oasis AET and scale, respectively (ellipse in Fig. 9a). Oasis AET and scale were averaged into to mm and 30 × 104 ha in the period in the middle reaches, respectively, pointing to a virtual water diversion of 14 × 108 m3 if there were no groundwater drawdown. This scenario was impossible because of policy-regulated water division to the lower reaches. The deficit was matched by groundwater abstractions. The situation was the same in the lower reaches, where the 30-year average oasis AET and scale were 442 mm and 9 × 104 ha, respectively, corresponding to a requirement of 5.5 × 108 m3 for land surface water division. This situation occurred in the 1950–1960s when the oasis scale in the middle reaches was relatively small. Real water diversion for oasis utilization in the middle reaches and lower reaches averaged approximately 12 × 108 m3 and 1.8 × 108 m3, respectively, from 1981 to 2010. If the decline in the groundwater system did not continue, the ideal oasis scale should be approximately 26 × 104 ha and 2 × 104 ha in the middle and lower reaches (bold red numbers in Fig. 9a), respectively, meaning that the ideal shrinkage of the oasis scale for a healthy groundwater system in the SYRB may be 11 × 104 ha. Notably, the above analysis was based on the exclusion of VLI when applying the module for discussion. Considering this part of water use would lead to more water consumption and a higher impact on the health of the underground water system.

Discussion

A 30-year basin water balance in the SYRB

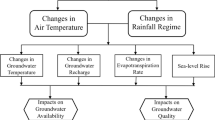

In the SYRB, mountainous discharges and abstractions of groundwater supported a large oasis AET requirement, combined with industrial water use and household water consumption. Sen’s slope was used to test T, which presented an overall increase across the whole basin (Fig. 9c), while P decreased in mountains and increased in plain areas during the 1981 to 2010 period. Under the background of climate change, mountainous discharges presented an overall decrease, while the extension of arable land led to an aggregation of land surface AET in the irrigated oasis (Fig. 10). Reservoir-canal-well systems, initially developed to support the large irrigation demand, led to dried-up river channels in addition to regional groundwater drawdown. Statistics in the SYRB revealed that the annual rate of groundwater drawdown in the lower area was at a high rate of 0.31 m/a, resulting in near-bare spring outflow for a relatively long time. The average drawdown rate was 0.17 m/a in the middle reaches. Spring outflow there declined at an annual rate of 0.017 × 108 m3/a during that time period [60].

Mountain discharges from the upper river basins vary over time due to the effects of climate change on land surface water flux, while hydrological responses in the middle and lower plains are predominantly impacted by human activities. A decrease in mountainous discharges, along with an increase in the oasis AET requirement in the middle and lower reaches, not only led to depressions of spring outflow and phreatic evaporation but also to a reduction in necessary water absorption by roots [61]. Degeneration of land cover would lead to a higher risk of oasis destruction due to interior and circumjacent desertification. In particular, the high risk of oasis survival in the lower reaches of the SYRB has been verified over the past several decades, coinciding with desert extension in other areas and with strengthening dust storms in northwestern China [62]. These impacts indicate the negative results of overexploitation on water resources and its gradual consequences for regional hydrology and ecology; additionally, these impacts serve as a warning for pursuing economic well-being at the expense of the environment. Our study could be considered a 30-year case example when the above contradictions were remarkable in inland river systems in arid regions.

Oasis and water management

For the large population (especially farmers) survival, resource shortage-induced water problems are still crucial to oasis health in the SYRB. Furthermore, an increase in air temperature, together with strengthened vegetation dynamics, facilitated regional AET requirements. According to this study, increasing precipitation suppressed oasis AET, and combined with a reduction in water utilization to some extent, the effectiveness was slight when compared with the former two factors. Under a background of warming and facing deterioration of the underground system, rational development of oasis soil and water needs more attention and better planning. In the late 2000s, strict rules were implemented to partition water resources between the middle and lower reaches (division part should not be less than 2.7 × 108 m3 in a year [63], corresponding to a suitable oasis area of 4 × 104 ha according to our study), to cut down groundwater abstraction to maintain a healthy underground system and to demonstrate advanced water-saving methods in experimental regions (which may lead to a decrease in the AET requirement). All of these methods have helped but not enough. On the one hand, we should further improve the crop types in oases by planting more low water consumption crops and reducing high water consumption crops. On the other hand, we can reduce cultivated land area, return farmland to forest and grassland, supervise ground water extraction and even close wells to protect the groundwater system. In addition, water diversion from outside the SYRB would be the key to achieving better socioeconomic development under the background of a changing climate.

Conclusion

In this study, various-source data were used to calibrate and determine the driving factors that influence net oasis water consumption and regional groundwater dynamics in the selected SYRB of arid northwestern China. Module analyses revealed a warming-dominated AET increase, while oasis extension led to large amounts of water consumption and remarkable drawdown of regional groundwater during the 1981 to 2010 period. The drawdown rates of regional groundwater averaged 0.17 m/a and 0.31 m/a in the middle and lower reaches, respectively, indicating an approximately continuous decline in the basin groundwater system. From the perspective of groundwater system recovery, our study quantitatively pointed to prominent gaps between real oasis scales and rational scales in both the middle and lower reaches. For a sustainable future of population survival and land surface ecology in the SYRB, moderate shrinkage of the oasis scale and water diversion from outside into the basin would be essential.

Availability of data and materials

The gauge-based hydrometeorological observations are available in China’s National Meteorological Information Center database at http://www.cma.gov.cn/; hydrological observational data are supplied by the Gansu Province Bureau of Hydrology and Water Resources Monitoring; well-monitored groundwater data are from administrative units, including the Gansu Province Bureau of Hydrology and Water Resources Monitoring, Gansu Province Geology Survey, and Gansu Province Environmental Protection Agency; the NDVI that supports the findings of this study are available from the Advanced Very High Resolution Radiometer (https://ecocast.arc.nasa.gov/) and the Moderate Resolution Imaging Spectroradiometer (http://glovis.usgs.gov/); NLCD data are supported by China’s National Land Cover Dataset (http://www.resdc.cn/); and the GLEAM-AET data that support the findings of this study are available on the VU University Amsterdam Geoservices website (http://geoservices.falw.vu.nl).

Abbreviations

- SYRB:

-

Shiyang River Basin

- T:

-

Temperature

- P:

-

Precipitation

- NDVI:

-

Normalized difference vegetation index

- AET:

-

Actual evapotranspiration

- GLEAM:

-

Global land evaporation Amsterdam model

- AVHRR:

-

Advanced very high resolution radiometer

- MODIS:

-

Moderate resolution imaging spectroradiometer

- IDW:

-

Inverse distance weighted

- NLCD:

-

China’s National Land Cover Dataset

- DTM:

-

Digital terrain mode

- DEM:

-

Digital elevation model

- AOI:

-

Area of interest

- MVC:

-

Maximum-value composite

- Dis.:

-

Discharge

- GW:

-

Groundwater

- Spr.:

-

Spring outflow

References

Scanlon BR, Jolly I, Sophocleous M, Zhang L. Global impacts of conversions from natural to agricultural ecosystems on water resources: quantity versus quality. Water Resour Res. 2007;43:W03437. https://doi.org/10.1029/2006.WR005486.

Guo Q, Yang Y, Xiong X. Using hydrologic simulation to identify contributions of climate change and human activity to runoff changes in the Kuye river basin, China. Environ Earth Sci. 2016;75(5):417.

Kniveton DR, Todd MC. Water resources in regional development: the Okavango river. J Hydrol. 2006;331(1):1–2. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jhydro2006.04.038.

Valdés-Pineda R, Pizarro R, García-Chevesich P, Valdés JB, Olivares C, Vera M, Balocchi F, Pérezd F, Vallejos C, Fuentes R, Abarza A, Helwig B. Water governance in Chile: availability, management and climate change. J Hydrol. 2014;519:2538–67. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jhydrol.2014.04.016.

Wang J, Li Y, Huang J, Yan T, Sun T. Growing water scarcity, food security and government responses in China. Global Food Secur. 2017;14:9–17. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.gfs.2017.01.003.

Li C, Wang L, Wang W, Qi J, Yang L, Zhang Y, Wu L, Cui X, Wang P. An analytical approach to separate climate and human contributions to basin streamflow variability. J Hydrol. 2018;2018(559):30–42.

Field CB, Barros VR, Dokken DJ, et al. Climate change 2014: impacts, adaptation, and vulnerability. Summaries, frequently asked questions, and cross-chapter boxes. A contribution of working group II to the fifth assessment report of the intergovernmental panel on climate change. Geneva: World Meteorological Organization; 2014.

Kang Y, Khan S, Ma X. Climate change impacts on crop yield, crop water productivity and food security–a review. Prog Nat Sci. 2009;19(12):1665–74. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.pnsc.2009.08.001.

Gorelick SM, Zheng C. Global change and the groundwater management challenge. Water Resour Res. 2015;51:3031–51.

Aeschbach-Hertig W, Gleeson T. Regional strategies for the accelerating global problem of groundwater depletion. Nature Geosci. 2012;5(12):853–61. https://doi.org/10.1038/ngeo1617.

Edmunds WM, Ma JZ, Aeschbach-Hertig W, Kipfer R, Darbyshire DPF. Groundwater recharge history and hydrogeochemical evolution in the Minqin Basin, North West China. Appl. Geochem. 2006;21(12):2148–70. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.apgeochem.2006.07.016.

Feng Q, Miao Z, Li ZX, Li JG, Si JH, Su YH, Chang Z. Public perception of an ecological rehabilitation project in inland river basins in northern China: success or failure. Environ Res. 2015;139:20–30.

Chen Q, Liu J. Development process and perspective on ecological risk assessment. Acta Ecol Sin. 2014;34(5):239–45.

Currell MJ, Han D, Chen Z, Cartwright I. Sustainability of groundwater usage in northern china: dependence on palaeowaters and effects on water quality, quantity and ecosystem health. Hydrol Process. 2012;26(26):4050–66.

Cheng G, Li X, Zhao W, Xu Z, Feng Q, Xiao S, Xiao H. Integrated study of the water-ecosystem-economy in the Heihe River Basin. Natl Sci Rev. 2014;1(3):413–28. https://doi.org/10.1093/nsr/nwu017.

Bao C, Fang CL. Water resources constraint force on urbanization in water deficient regions: a case study of the Hexi Corridor, arid area of NW China. Ecol Econ. 2007;62(3):508–17. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ecolecon.2.006.07.013.

Gu CL, Wu LY, Cook L. Progress in research on Chinese urbanization. Front Archit Res. 2012;1(2):101–49. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.foar.2012.02.013.

Schaller MF, Fan Y. River basins as groundwater exporters and importers: implications for water cycle and climate modeling. J Geophys Res Atmos. 2009;114(D04103):1–21. https://doi.org/10.1029/2008JD010636.

Grogan DS, Zhang F, Prusevich A, Lammers RB, Wisser D, Glidden S, Li C, Frolking S. Quantifying the link between crop production and mined groundwater irrigation in China. Sci Total Environ. 2015;511:161–75. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.scitotenv.2014.11.076.

Langroodi SHM, Masoum MG, Nasiri H, Javi ST. Spatial and temporal variability analysis of groundwater quantity to land-use/land-cover change in the Khanmirza agricultural plain in Iran. Arab J Geosci. 2015;8(10):8385–97. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12517-015-1786-7.

Li Z, Quan J, Li XY, Wu XC, Wu HW, Li YT, Li GY. Establishing a model of conjunctive regulation of surface water and groundwater in the arid regions. Agr. Water Manage. 2016;174:30–8. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.agwat.2016.04.030.

Sun P, Wu Y, Xiao J, Hui J, Hu J, Zhao F, Qiu L, Liu S. Remote sensing and modeling fusion for investigating the ecosystem water-carbon coupling processes. Sci Total Environ. 2019. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.scitotenv.2019.134064.

Yang Q, Mu H, Wang H, Ye X, Ma H, Martín JD. Quantitative evaluation of groundwater recharge and evaporation intensity with stable oxygen and hydrogen isotopes in a semi-arid region, northwest china. Hydrol Process. 2018;32:1130–6.

Liu M, Jiang Y, Xu X, Huang Q, Huo Z, Huang G. Long-term groundwater dynamics affected by intense agricultural activities in oasis areas of arid inland river basins, northwest China. Agric Water Manag. 2018;203:37.

Hao Y, Xie Y, Ma J, Zhang W. The critical role of local policy effects in arid watershed groundwater resources sustainability: a case study in the Minqin oasis, China. Sci Total Environ. 2017;601–602:1084–96.

Balugani E, Lubczynski MW, Reyes-Acosta L, Van Der Tol C, Francés AP, Metselaar K. Groundwater and unsaturated zone evaporation and transpiration in a semi-arid open woodland. J Hydrol. 2017;547:54–66.

Xie Y, Gong J, Sun P, Gou X. Oasis dynamics change and its influence on landscape pattern on Jintaoasis in arid China from 1963a to 2010a: integration of multi-source satellite images. Int J Appl Earth Obs Geoinf. 2014;33:181–91.

Yang G, Li F, Chen D, He X, Xue L, Long A. Assessment of changes in oasis scale and water management in the arid Manas River Basin, north western China. Sci Total Environ. 2019;691:506–15.

Sefelnasr A, Gossel W, Wycisk P. Groundwater management options in an arid environment: the nubian sandstone aquifer system, eastern sahara. J Arid Environ. 2015;122(2):46–58.

Bormann H, Ahlhorn F, Klenke T. Adaptation of water management to regional climate change in a coastal region–Hydrological change vs. community perception and strategies. J. Hydrol. 2012;454:64–75. https://doi.org/10.1016/.j.jhydrol.2012.05.063.

Irmak S, Kabenge I, Rudnick D, Knezevic S, Woodward D, Moravek M. Evapotranspiration crop coefficients for mixed riparian plant community and transpiration crop coefficients for common reed, cottonwood and peach-leaf willow in the Platte River Basin, Nebraska-USA. J Hydrol. 2013;481:177–90. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jhydrol.2012.12.032.

Wu B, Zheng Y, Wu X, Tian Y, Han F, Liu J, Zheng C. Optimizing water resources management in large river basins with integrated surface water-groundwater modeling: a surrogate-based approach. Water Resour Res. 2015;51(4):2153–73. https://doi.org/10.1002/2014WR016653.

Yao Y, Liang S, Cheng J, Liu S, Fisher JB, Zhang X, Jia K, Zhao X, Qin Q, Zhao B, Han S, Zhou G, Li Y, Zhao S. MODIS-driven estimation of terrestrial latent heat flux in China based on a modified Priestley-Taylor algorithm. Agric For Meteorol. 2013;171:187–202. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.agrformet.2012.11.016.

Li C, Qi J, Yang L, Wang S, Yang W, Zhu G, Zou S. Zhang F regional vegetation dynamics and its response to climate change—a case study in the Tao River Basin in Northwestern China. Environ Res Lett. 2014;9(12):125003. https://doi.org/10.1088/1748-9326/9/12/125003.

Jay S, Potter C, Crabtree R, Genovese V, Weiss D, Kraft M. Evaluation of modelled net primary production using MODIS and landsat satellite data fusion. Carbon Bal Manage. 2016;11:8.

Potter C, Gross P, Genovese V, Smith M. Net primary productivity of forest stands in new hampshire estimated from landsat and MODIS satellite data. Carbon Balance Manage. 2007;2:9. https://doi.org/10.1186/1750-0680-2-9.

Li G, Zhang F, Jiang Y, Liu Y, Sun G. Response of evapotranspiration to changes in land use and land cover and climate in China during 2001–2013. Sci Total Environ. 2017;596:256–65.

Wang H, Xiao W, Zhao Y, Wang Y, Hou B, Zhou Y, Yang H, Zhang X, Cui H. The spatiotemporal variability of evapotranspiration and its response to climate change and land use/land cover change in the three gorges reservoir. Water. 2019;11(9):1–20. https://doi.org/10.3390/w11091739.

Zhao F, Wu Y, Sivakumar B, Long A, Qiu L, Chen J, Wang L, Liu S, Hu H. Climatic and hydrologic controls on net primary production in a semiarid loess watershed. J Hydrol. 2019;568:803–15. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jhydrol.2018.11.031.

Ago E, Serca D, Agbossou E, Galle S, Aubinet M. Carbon dioxide fluxes from a degraded woodland in West Africa and their responses to main environmental factors. Carbon Balance Manage. 2015;10:22.

Ardo J. Comparison between remote sensing and a dynamic vegetation model for estimating terrestrial primary production of Africa. Carbon Balance Manage. 2015;10:8. https://doi.org/10.1186/s13021-015-0018-5.

Pedro-Monzonís M, Solera A, Ferrer J, Estrela T, Paredes-Arquiola J. A review of water scarcity and drought indexes in water resources planning and management. J Hydrol. 2015;527:482–93. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jhydrol.2015.05.003.

Chang G, Wang L, Meng L, Zhang W. Farmers’ attitudes toward mandatory water-saving policies: a case study in two basins in northwest China. J Environ Manage. 2016;181:455–64. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jenvman.2016.07.007.

Xiao SC, Li JX, Xiao HL, Liu FM. Comprehensive assessment of water security for inland watersheds in the Hexi Corridor, Northwest China. Environ Geol. 2008;55(2):369–76. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00254-007-0982-5.

Wei W, Zhao J, Wang XF, Zhou ZY, Li HL. Landscape pattern MACRS analysis and the optimal utilization of Shiyang River Basin based on RS and GIS approach. Acta Ecol Sin. 2009;29(4):216–21.

Bai J, Chen X, Li L, Luo G, Yu Q. Quantifying the contributions of agricultural oasis expansion, management practices and climate change to net primary production and evapotranspiration in croplands in arid northwest China. J Arid Environ. 2014;100:31–41. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jaridenv.2013.10.004.

Ma J, Ding Z, Edmunds WM, Gates JB, Huang T. Limits to recharge of groundwater from Tibetan plateau to the Gobi desert, implications for water management in the mountain front. J Hydrol. 2009;364(1):128–41. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jhydrol.2008.10.010.

Mu M, Zhang X, Gao P, Wang F. Theory of double mass curves and its applications in hydrology and meteorology. J China Hydrol. 2010;30(4):47–51.

Liu W. Evaluating remotely sensed monthly evapotranspiration against water balance estimates at basin scale in the Tibetan Plateau. Hydrol Res. 2018;49(6):1977–90.

Liu W, Wang L, Zhou J, Li Y, Sun F, Fu G, Li X, Sang Y. A worldwide evaluation of basin-scale evapotranspiration estimates against the water balance method. J Hydrol. 2016;538:82–95.

Martens B, Gonzalez Miralles D, Lievens H, Van Der Schalie R, De Jeu RA, Fernández-Prieto D, Beck HE, Dorigo W, Verhoest N. GLEAM v3: satellite-based land evaporation and root-zone soil moisture. Geosci Model Dev. 2017;10(5):1903–25.

Bai P, Liu X. Intercomparison and evaluation of three global high-resolution evapotranspiration products across China. J Hydrol. 2018;566:743–55.

Ma Z, Yan N, Wu B, Stein A, Zhu W, Zeng H. Variation in actual evapotranspiration following changes in climate and vegetation cover during an ecological restoration period (2000–2015) in the Loess Plateau, China. Sci Total Environ. 2019;689:534–45.

Yao G, Wang W, Li J. Evaluation of various remote sensing evapotranspiration products in Han River Basin. China Rural Water Hydropower. 2018;5:103–8.

Huang J, Wang W, Cui W, Wang P. Evaluation of several evapotranspiration products over Yunnan–Guizhou region in China. Yangtze River. 2019;50(12):73–90.

Sen PK. Estimates of the regression coefficient based on Kendall’s tau. J Am Stat Assoc. 1968;63(324):1379–89.

Ingdal M, Johnsen R, Harrington DA. The Akaike information criterion in weighted regression of immittance data. Electrochimica Acta. 2019;317(10):648–53. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.electacta.2019.06.030.

Li W, Chen Z, Li B, Fu A, Zhou H. Analysis of water demand and stability for oasis in Kaidu-Kongque River Basin, Southern Xinjiang. J Glaciol Geocryol. 2012;34(6):1470–7.

Dong Z, Man D, Luo W, Qian G, Wang J, Zhao M, Liu S, Zhu G, Zhu S. Horizontal aeolian sediment flux in the Minqin area, a major source of Chinese dust storms. Geomorphology. 2010;116(1):58–66. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.geomorph.2009.10.008.

Xiong W, Li C, Zuo Y, Li W, Yang W, Yang L, Zhang S, Zhang J. Rational utilization of water resources in South Shiyang River Basin, Institute of water conservancy and hydropower survey and design in Gansu Province. Report; 2012.

Zhao F, Wu Y, Yao Y, Sun K, Zhang X, Winowiecki L, Vagen T, Xu J, Qiu L, Sun P, Sun Y. Predicting the climate change impacts on water-carbon coupling cycles for a loess hilly-gully watershed. J Hydrol. 2020;581:124388. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jhydrol.2019.124388.

Wang Z, Jiang J, Fang G, Chen Z, Cai M, Li W. Analysis on the suitable scale of the Aksu Oasis under the limit of water resources. J Glaciol Geocryol. 2019;41(4):986–92.

Xiong W, et al. Key Comprehensive Management and Planning of the Water Utilization in the SYRB. Report; 2007.

Acknowledgements

We are grateful to the following institutions, including NASA, USGS, Gansu Province Bureau of Hydrology and Water Resources Monitoring, Meteorological Bureau of China, VU University Amsterdam, and so on for allowing us open access to data collections and archives.

Funding

This study was supported by the National Key Research and Development Programs of China (No. 2017YFC0504306) and partially supported by the National Natural Science Foundation of China (Grant No. 41671017) and the National Key Research and Development Programs of China (No. 2017YFC0504801).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

LC, WL and HZ designed the study and drafted the manuscript; XX, WW and ZY collected data and conducted analysis and module regressions; and WJ and LJ conducted the field surveys and manuscript revisions. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/. The Creative Commons Public Domain Dedication waiver (http://creativecommons.org/publicdomain/zero/1.0/) applies to the data made available in this article, unless otherwise stated in a credit line to the data.

About this article

Cite this article

Lei, W., Changbin, L., Xuhong, X. et al. The impact of increasing land productivity on groundwater dynamics: a case study of an oasis located at the edge of the Gobi Desert. Carbon Balance Manage 15, 7 (2020). https://doi.org/10.1186/s13021-020-00142-7

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/s13021-020-00142-7