Abstract

Background

In a sedated patient, airway compression by a large mediastinal mass can cause acute fatal cardiopulmonary arrest. Extracorporeal membrane oxygenation (ECMO) has been investigated to protect the airway and provided cardiopulmonary stability. The use of ECMO in the management of mediastinal masses was reported, however, the management complicated by cardiopulmonary arrest is poorly documented.

Case presentation

32-year-old female presented with acute onset of left arm swelling and subacute onset of dry cough. Further investigation showed a deep venous thrombosis in left upper extremity as well as a large mediastinal mass. She underwent mediastinoscopy with biopsy of the mass which was complicated by cardiopulmonary arrest secondary to airway obstruction by the mediastinal mass. Venoarterial ECMO was initiated, while concurrently treating with a chemotherapy. The mediastinal mass responded to the chemotherapy and reduced in size during 2 days of ECMO support. She was extubated successfully and decannulated after 2 days of ECMO and discharged later.

Conclusions

Extracorporeal membrane oxygenation can serve as a viable strategy to facilitate cardiopulmonary support while concurrently treating the tumor with chemotherapy, ultimately allowing for the recovery of cardiopulmonary function, and achieving satisfactory outcomes.

Similar content being viewed by others

Background

An anterior mediastinal mass significantly increases the risk of airway compromise and circulatory arrest [1]. In a sedated patient, airway compression by a large mediastinal mass can cause acute fatal cardiopulmonary arrest. Extracorporeal membrane oxygenation (ECMO) has been investigated to protect the airway and provided cardiopulmonary stability. However, the use of ECMO in the management of mediastinal masses is poorly documented.

Case presentation

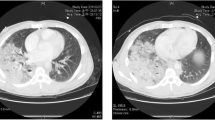

This previously healthy 32-year-old female presented to the emergency department with one day of left upper extremity (LUE) swelling, two-month history of dry cough, and one-year history of progressive exertional dyspnea. Further investigation revealed an acute LUE deep venous thrombosis (DVT) as well as a large mediastinal mass. Computer tomography revealed a large heterogeneous 12 × 8 × 14 cm soft tissue mass within the anterior mediastinum with local mass-effect on the heart resulting in compression of the right main pulmonary artery and distal trachea against the vertebral column (Fig. 1). There was an acute LUE DVT and stenosis of superior vena cava (SVC) and right distal subclavian vein (Fig. 1). Heparin drip was initiated, and she was transferred to our facility for a mediastinoscopy with biopsy of the mass. Induction of general anesthesia and intubation were performed without any issues. She tolerated ventilation during her uncomplicated mediastinoscopy. After the surgical team and anesthesiologists discussed the timing of extubation, the decision was made to proceed with extubation after the procedure. However, several minutes after extubation, she developed profound hypoxia refractory to bag mask ventilation and went into cardiopulmonary arrest (CPA). One minute of cardiopulmonary resuscitation (CPR) was required prior to achieving return of spontaneous circulation (ROSC). Reintubation was performed during this time and right femoral arterial and left femoral venous access was obtained. The decision was made to hold off on placing ECMO cannulas at this point since she was easily able to be ventilated with normal oxygenation. However, as her sedation wore off, the second CPA secondary to profound hypoxia happened while she was still intubated. One minute of CPR was performed and she was re-sedated and paralyzed with subsequent ROSC. Venoarterial (VA) ECMO was chosen to support her heart function damaged by two CPA events and due to the fact that the superior vena cava (SVC) was compressed by the mass and not suitable for internal jugular venous return in VV ECMO. An arterial cannula was placed in the right femoral artery with a distal perfusion cannula and a venous cannula was placed in the left femoral vein (Fig. 1). VA ECMO was initiated. A preliminary diagnosis of lymphoma was made, and she was initiated on EPOCH chemotherapy regimen and steroids on the evening of the cannulation of ECMO. Her hemodynamics and respiratory status were clinically improved after the initiation of the chemotherapy. She was successfully extubated and decannulated on post ECMO day 2. The final pathology demonstrated B cell lymphoma. Repeated CT on post ECMO day 11 showed significant reduction in size of the mediastinal mass (Fig. 2). She was discharged home on post ECMO day 12 on apixaban for her DVT with plans to continue her EPOCH regimen.

Pretreatment chest computed tomography (A) a mediastinal mass compressing the distal trachea against the vertebral column (white arrow). (B) Stenosis of the superior vena cava compressed by a mediastinal mass (white arrow). (C) a large heterogeneous 12 × 8 × 14 cm soft tissue mass within the anterior mediastinum (D) Xray abdomen after VA ECMO cannulation

Discussion and conclusions

We present the use of ECMO as a bridge to urgent chemotherapy. Emergent ECMO has been documented in several case reports involving patients with mediastinal masses [2]. ECMO was indicated in the patient because the patient sustained two circulatory arrests caused by hypoxia: the first after extubation and the second after re-intubation due to compression of her trachea distal to the endotracheal tube. We could not therefore extubate her without first shrinking her mediastinal mass. Frey TK et al. reported the use of ECMO in a patient receiving chemotherapy [3]. Two ECMO options are available: venoarterial (VA) and venovenous (VV). In our case, considering the presence of cardiac arrest and compressed SVC, VA ECMO was deemed beneficial for both cardiac and respiratory support. However, in the absence of cardiac issues, VV ECMO with endoscopic stenting for airway protection could be an alternative option [4, 5]. In our case, the mass compressed the airway from the distal trachea to right and left main bronchi. The compression area was too distal and long to place on stent.

Currently, there are no established guidelines for the rescue use of ECMO in cases involving mediastinal masses. Nevertheless, some authors have suggested implementing a contingency plan to mitigate potential complications. They recommended placing 5 Fr sheaths in the femoral vein and artery before intubation in high-risk patients to enable swift cannulation in the event of unstable hemodynamics [6]. We concur with this approach, as using a guide wire during placement may facilitate rapid cannulation. Another factor to consider in this case is the possibility of tumor lysis syndrome (TLS), which often occurs following the initiation of cytotoxic therapy in patients with clinically aggressive and highly aggressive tumors such as lymphoma. TLS is characterized by the massive lysis of tumor cells, releasing large amounts of potassium, phosphate, and nucleic acids into the systemic circulation [7]. In our case, the patient responded well to chemotherapy and there was no siginificant issue related to TLS while on VA ECMO support. In some cases, ECMO might be crucial in managing specific TLS-related consequences, including electrolyte abnormalities [8].

This case is an example of a patient experiencing significant respiratory compromise secondary to mechanical compression from a mediastinal mass, resulting in CPA. We have demonstrated that VA ECMO can serve as a viable strategy to facilitate cardiopulmonary support while concurrently treating the tumor with chemotherapy, ultimately allowing for the recovery of cardiopulmonary function, and achieving satisfactory outcomes.

Data availability

No datasets were generated or analysed during the current study.

Abbreviations

- ECMO:

-

Extracorporeal membrane oxygenation

- LUE:

-

Left upper extremity

- DVT:

-

Deep venous thrombosis

- SVC:

-

Superior vena cava

- CPA:

-

Cardiopulmonary arrest

- CPR:

-

Cardiopulmonary resuscitation

- ROSC:

-

Return of spontaneous circulation

- VA:

-

Venoarterial

- VV:

-

Venovenous

References

Narang S, Harte BH, Body SC. Anesthesia for patients with a mediastinal mass. Anesthesiol Clin North Am. 2001;19:559–79.

Chao VT, Lim DW, Tao M, Thirugnanam A, Koong HN, Lim CH. Tracheobronchial obstruction as a result of mediastinal mass. Asian Cardiovasc Thorac Ann. 2006;14:e17–8.

Frey TK, Chopra A, Lin RJ, Levy RJ, Gruber P, Rheingold SR, et al. A child with anterior mediastinal mass supported with veno-arterial extracorporeal membrane oxygenation. Pediatr Crit Care Med. 2006;7:479–81.

Nokes BT, Vaszar L, Jahanyar J, Swanson KL. VV-ECMO-Assisted high-risk endobronchial stenting as rescue for asphyxiating Mediastinal Mass. J Bronchol Interv Pulmonol. 2018;25:144–7.

Booka E, Kitano M, Nakano Y, Mihara K, Nishiya S, Nishiyama R, et al. Life-threatening giant esophageal neurofibroma with severe tracheal stenosis: a case report. Surg Case Rep. 2018;4:107.

Ramanathan K, Leow L, Mithiran H. ECMO and adult mediastinal masses. Indian J Thorac Cardiovasc Surg. 2021;37:338–43.

Cairo MS, Bishop M. Tumour lysis syndrome: new therapeutic strategies and classification. Br J Haematol. 2004;127:3–11.

Shekar K, Fraser JF, Smith MT, Roberts JA. Pharmacokinetic changes in patients receiving extracorporeal membrane oxygenation. J Crit Care. 2012;27:741.

Acknowledgements

Not applicable.

Funding

The authors received no financial support for the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

DW was the lead author in the original draft and images. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate

Albany Med Office of Research Affairs confirmed this case report did not require review or approval by IRB as long as consent for the study was obtained from the patient.

Consent for publication

Consent for publication was obtained from the patient.

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/. The Creative Commons Public Domain Dedication waiver (http://creativecommons.org/publicdomain/zero/1.0/) applies to the data made available in this article, unless otherwise stated in a credit line to the data.

About this article

Cite this article

Wilkinson, D., Yeung, E., Samy, S. et al. Extracorporeal membrane oxygenation bridging for chemotherapy in obstructing mediastinal mass after cardiopulmonary arrest. J Cardiothorac Surg 19, 382 (2024). https://doi.org/10.1186/s13019-024-02918-1

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/s13019-024-02918-1