Abstract

Background

Anomalous systemic arterial supply to normal basal lung segments is a rare congenital malformation, in which aberrant arteries arising from the systemic circulation flow into the basal segment of the lung and return to normal pulmonary veins without abnormal bronchial branching. It presents a left-to-right shunt, resulting in volume overload of the pulmonary circulation, and consequently, pulmonary hypertension. Therefore, nearly all cases require surgery. Herein, we present a case, in which indocyanine green was used to demarcate the lung segment perfused by an anomalous systemic artery.

Case presentation

A 15-year-old boy was diagnosed with an anomalous artery originating from the celiac artery and supplying the right dorsobasal lung segment (S10). Via three-port video-assisted thoracoscopic surgery, the anomalous artery was ligated and processed with an auto-stapler. Indocyanine green was injected intravenously to identify the tissue perfused by the anomalous artery, and the lung was resected.

Conclusions

With anomalous systemic arterial supply to normal basal lung segments, indocyanine green can be particularly helpful in identifying the boundaries of the perfused area. Then, the affected tissue can be resected by thoracoscopic surgery.

Similar content being viewed by others

Background

Anomalous systemic arterial supply (ASA) to normal basal lung segments is a rare congenital malformation, in which aberrant arteries from the systemic circulation flow into the basal segments of the lung and return to the normal pulmonary veins, with normal bronchial branching [1]. Although it has been classified as Pryce type I pulmonary sequestration (PS), in recent years, it is considered an independent condition. It presents a left-to-right shunt because blood from the systemic circulation returns to the pulmonary veins, resulting in volume overload of the pulmonary circulation, and consequently, pulmonary hypertension. In advanced cases, hemoptysis and heart failure occur due to pulmonary hypertension; therefore, nearly all cases require surgery. Herein, we report a case, in which an aberrant artery arose from the celiac artery and supplied the right dorsobasal lung segment (S10). Indocyanine green (ICG) was particularly useful for identifying the demarcation line of the perfused area.

Case presentation

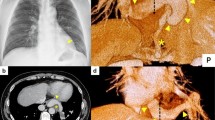

A 15-year-old boy was found to have an abnormal shadow on a chest radiographic examination at a school checkup. He was asymptomatic and had no history of heart disease. Physical examination and laboratory findings were within the normal limits. Chest radiographic findings showed a slight opacity around the right cardiophrenic angle. Non-contrasted chest computed tomography (CT) findings showed a rod-shaped shadow from the inside of the right S10 segment toward the pulmonary ligaments (Fig. 1a–c). On contrast-enhanced (CE) chest CT and three-dimensional angiography indicated that aberrant branches from the celiac artery flowed into the right S10 segment (Fig. 1d–e). Bronchoscopy was not performed because of declination of consent. Meanwhile, CT findings showed no abnormal bronchial bifurcation. Therefore, we diagnosed ASA to the normal S10 segment.

Non-contrasted axial (a, b) and coronal (c) computed tomography (CT) images; d contrast-enhanced coronal CT image; and e three-dimensional (3D) angiography showed the aberrant artery from the celiac artery (yellow arrow) flowing into the right dorsobasal segment (S10). f The findings of 3D angiography at the 3-month follow-examination showed that the remnants of the anomalous artery had become cord-like, without aneurysmal formation

Given the option of either catheter embolization of the anomalous artery or lung resection, the patient chose the latter, and we performed three-port video-assisted thoracic surgery as follows. First, the aberrant artery was identified. When the lower lobe of the right lung was raised to the cranial side and the pulmonary ligament was detached, an aberrant artery that ascended through the diaphragm and flowed into the S10 segment was confirmed. The central side of the artery was ligated, and the artery was processed with an auto-stapler (Fig. 2a, b). The outer diameter of the aberrant artery was 8 mm. Subsequently, to visualize the demarcation line based on near- infrared (NIR) fluorescence imaging, 5 mg of ICG was injected intravenously to identify the area perfused by the anomalous artery. We used 1688 AIM (Stryker, Tokyo, Japan) NIR thoracoscopy system in this case. Then, the lung parenchyma was resected using an auto-stapler (Fig. 2c, d). Finally, we completed the wedge resection of S10 segment. Histopathologically, the endometrium of the dilated aberrant artery was thickened, and the intime thickening continued to the peripheral pulmonary artery (Fig. 2e, f). In addition, plexiform lesions and vasculitis were found in the pulmonary artery. These were considered to be findings of pulmonary hypertension due to ASA. At the 3-month follow up, the patient was in good health and CE-CT showed that the remnants of the anomalous artery had become cord-like, without aneurysmal formation (Fig. 1f). Written informed consent was obtained from the patient for the publication of this report and its accompanying images.

Intraoperative and pathological findings. a The aberrant artery (white arrow) was identified. b The central side of the aberrant artery (white arrow) was ligated, and the artery was processed with an auto-stapler. The black arrow indicates the inferior vena cava and the asterisk indicates the diaphragm. c The region perfused by the anomalous artery was clearly shown by intravenous injection of ICG, and d the segment was resected using an auto-stapler. e Macroscopically, a large blood vessel dilated in the resected lung was observed. The length of the red bar is 1.0 cm. f Histopathologically, the endometrium of the dilated aberrant artery was thickened, and the intime thickening continued to the peripheral pulmonary artery (Hematoxylin–eosin stain, loupe magnification). The length of the black bar is 1.0 cm

Discussion and conclusions

ASA to the normal basal segments was formerly known as PS. Most aberrant systemic arteries that drain into the lungs originate directly from either the thoracic or abdominal aorta. Wei et al. examined 2625 cases of PS; only one case originated from the celiac artery, an extremely rare finding [2]. Even in Japan, there were only 10 reported cases in the last 30 years (Table 1) [3, 4]. Seven patients were male and three were female, with an average age of 26.2 years. In seven and three cases, ASA was observed on the right and left sides, respectively. All patients underwent surgery. Until 2010, there were many reported cases, in which the aberrant artery was ligated and dissected; however, recently, with the development of auto-suture, most cases were treated aberrant artery with auto-suture. However, a previous report indicated that it is better to ligate the central side of auto-suture as insurance for the event of misfire [3].

The management of asymptomatic PS is controversial. Surgical resection is recommended because of the possibility of hemorrhage and heart failure secondary to the progression of pulmonary hypertension in advanced cases. In recent years, successful cases of endovascular coil embolization have also been reported [5].

In recent years, ICG has been extensively used in the field of general thoracic and pulmonary surgery, such as in the identification of the demarcation line in lung segmentectomy or evaluation of the blood flow of the bronchial anastomosis in bronchoplasty [6, 7].

The strategy underlying surgery for ASA to the normal basal segment is excision of the lung area perfused by the anomalous artery. We have previously reported cases, in which ICG was useful in identifying the borders of Pryce type III intralobular sequestration [8]. To our knowledge, this is the first study to use ICG to identify the area of the normal basal segment perfused by an anomalous arterial supply (Pryce type I intralobular PS); we could clearly identify the demarcation line of the perfused area with ICG. In conclusion, ICG was particularly helpful in identifying the boundaries of the perfused area, and surgery was performed safely.

Availability of data and materials

All data generated or analyzed during this study are included in this published article.

Abbreviations

- ASA:

-

Anomalous systemic arterial supply

- PS:

-

Pulmonary sequestration

- CT:

-

Computed tomography

- CE:

-

Contrast-enhanced

- ICG:

-

Indocyanine green

- NIR:

-

Near-infrared

References

Campbell DC, Murney JA, Dominy DE. Systemic arterial blood supply to a normal lung. JAMA. 1962;182:497–9.

Wei Y, Li F. Pulmonary sequestration: a retrospective analysis of 2625 cases in China. Eur J Cardiothorac Surg. 2011;40:e39-42.

Hachisuka Y, Fujioka S, Uomoto M. A case of intralobar sequestration with an aberrant artery arising from the celiac artery. Jpn J Chest Surg. 2021;35:188–92. https://doi.org/10.2995/jacsurg.35.188. (in Japanese)

Utsumi T, Hino H, Kuwauchi S, Zempo N, Ishida K, Maru N, et al. Anomalous systemic arterial supply to the basal segment of the lung with giant aberrant artery: a case report. Surg Case Rep. 2020;6:285.

Machida Y, Motono N, Matsui T, Usuda K, Uramoto H. Successful endocascular coil embolization in an elder and asymptomatic case of anomalous systemic arterial supply to the normal basal segment. Int J Surg Case Rep. 2017;34:103–5.

Motono N, Iwai S, Funasaki A, Sekimura A, Usuda K, Uramoto H. Low-dose indocyanine green fluorescence-navigated segmentectomy: prospective analysis of 20 cases and review of previous reports. J Thorac Dis. 2019;11:702–7.

Uramoto H, Motono N. Indocyanine green fluorescence detects the blood flow of the bronchial anastomosis for bronchoplaasty “case report.” Ann Med Surg (Lond). 2020;59:151–2.

Motono N, Iwai S, Funasaki A, Sekimura A, Usuda K, Uramoto H. Indocyanine green fluorescence-guided thoracoscopic pulmonary resection for intralobar pulmonary sequestration: a case report. J Med Case Rep. 2019;13:228.

Acknowledgements

We would like to thank Editage (www.editage.jp) for English language editing.

Funding

Not applicable.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

YI composed the manuscript, and all the remaining authors provided critical edits to the final draft. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate

The institutional review boards of Kanazawa Medical University approved the protocol (approval number, M416).

Consent for publication

Written informed consent was obtained from the patient for the publication of this report and its accompanying images.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary Information

Additional file 1: Intraoperative findings. The aberrant artery that ascended through the diaphragm and flowed into the S10 segment was confirmed. The central side of the aberrant artery was ligated, and the artery was processed with an auto-stapler. The region perfused by the anomalous artery was clearly shown by intravenous injection of indocyanine green, and the segment was resected using an auto-stapler.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/. The Creative Commons Public Domain Dedication waiver (http://creativecommons.org/publicdomain/zero/1.0/) applies to the data made available in this article, unless otherwise stated in a credit line to the data.

About this article

Cite this article

Iijima, Y., Ishikawa, M., Iwai, S. et al. Role of indocyanine green in anomalous arterial supply to the normal dorsobasal segment of the lung. J Cardiothorac Surg 17, 52 (2022). https://doi.org/10.1186/s13019-022-01791-0

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/s13019-022-01791-0