Abstract

Background

The Total Abdominal Colectomy (TAC) is the recommended procedure for Fulminant Clostridium Difficile Colitis (FCDC), however, occasionally, FCDC is also treated with partial colectomies. The purpose of the study was to identify the outcomes of partial colectomy in FCDC cases.

Method

The National Surgical Quality Improvement Program database was accessed and eligible patients from 2012 through 2016 were reviewed. Patients 18 years and older who were diagnosed with FCDC and who underwent colectomies were included in the study. Patients’ demography, clinical characteristics, comorbidities, mortality, morbidities, length of hospital stay and discharge disposition were compared between the group who underwent partial colectomy and the group who underwent TAC. Univariate analysis followed by propensity matching was performed. A P value of < 0.05 is considered as statistically significant.

Results

Out of 491 patients who qualified for the study, 93 (18.9%) patients underwent partial colectomy. The pair matched analysis showed no significant difference in patients’ characteristics and comorbidities in the two groups. There was no significant difference found in mortality between the two groups (30.1% vs. 30.1%, P > 0.99). There were no differences found in the median [95% CI] hospital length of stay (LOS) (23 days [19–31] vs. 21 [17–25], P = 0.30), post-operative complications (all P > 0.05), and discharged disposition to home ( 33.8% vs. 43.1%) or transfer to rehab (21.55 vs. 12.3%, P = 0.357) between the TAC and partial colectomy groups.

Conclusion

The overall 30 days mortality remains very high in FCDC. Partial colectomy did not increase risk of mortality or morbidities and LOS.

Level of evidence

Level IV.

Study type

Observational cohort.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Fulminant Clostridium Difficile Colitis (FCDC) is one of the severe conditions of colon that is associated with very high mortality [1]. Approximately 4% of patients with Clostridium difficile colitis progress into fulminant course [2]. Aggressive resuscitation and early colectomy resulted in lower mortality [3, 4]. Total abdominal colectomy (TAC) is a standardized procedure for FCDC [5].

Alternate to TAC, another procedure was proposed almost 10 years ago, loop ileostomy (LI) and colonic lavage [6]. This new procedure was compared to TAC but no significant difference in overall mortality was found in a small study including 10 patients of (LI) compared to 13 patients of TAC [7].

Recent studies from the NSQIP database showed colectomy is still the procedure of choice [3, 8] but as an alternative to TAC, studies suggest a partial colectomy which does not appear to increase mortality [8]. In addition, the partial colectomy could ensure that part of the colon can be saved thus minimizing the metabolic consequences that ensues with TAC [9]. The study that compared the partial colectomy with standardized total abdominal colectomy for FCDC adjusted the characteristics of patients on multivariable logistic regression analysis [8]. However, propensity score comparison methodology was reported to be a better mode of performing observational studies [10]. As a result, we decided to conduct a study using propensity score matching analysis to find out the outcomes of patients who underwent partial colectomy for FCDC.

Methods

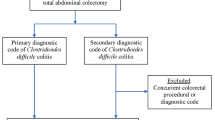

All adult patients age 18 years and older who were diagnosed with Clostridium difficile colitis and underwent emergency colectomy for the indication of Clostridium difficile colitis were included in the study. The data came from the National Surgical Quality Improvement Program (NSQIP) database from the calendar years 2012–2016. The American College of Surgeons developed the NSQIP database for the improvement of outcomes in surgical patients [11]. More than 700 institutions across the US participate in the NSQIP. The Clostridium difficile colitis defined as if the patient develops diarrhea with positive Clostridium difficile on laboratory test of stool by culture or PCR assay or Glutamate dehydrogenase EIA/ latex agglutination or cytotoxin test. Excluded from the study all emergency colectomies that were performed other than the indication of Clostridium difficile colitis. All elective colectomies were also excluded from the study.

We analyzed two groups, (partial colectomy [when a segment of the colon {right sided or left sided} was removed] versus total colectomy [where the entire colon was removed]), looking at gender, race, preoperative sepsis status, white blood cell counts, blood transfusion before the surgery and ventilator dependent respiratory failure prior to surgery, the American Society of Anesthesiologists (ASA) classification of the surgery, wound classification and comorbidities; history of diabetes mellitus (DM), smoking, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD), ascites, hypertension on medication (HTN), congestive heart failure, chronic renal failure (CRF), CRF on dialysis (CRF-D), disseminated cancer, steroid use. All comorbidities, sepsis and septic shock were defined as per NSQIP data dictionary.

The primary outcome of the study was 30 days all-cause mortality, while secondary outcomes were post-operative complications, hospital length of stay and discharge disposition.

Statistics

First, patient demographic information and outcomes were summarized using summary statistics (median with interquartile range (IQR) [first quartile–third quartile]) for continuous variables, and frequency and percentage for categorical variables). Then, the group that underwent total abdominal colectomy was compared with the group that underwent partial colectomy on patient’s demography, diseases severity, comorbidities, and outcomes. The Wilcoxon Rank Sum test was used for continuous variables, and the Chi-square test was used for the categorical variables.

The propensity score for total abdominal colectomy was calculated for each patient and the one-to-one matching was performed using the “nearest neighbor” as the matching method to pair a subject who had TAC with the subject who underwent partial colectomy. The propensity score matching was performed using the R package “MatchIt” [12]. The propensity scores were calculated using all the variables that may have impacted the decision to perform one procedure type versus other procedure type and that included (gender, age, race [white versus non-white], sepsis status, blood transfusion, respiratory failure, ASA class, wound class and all comorbidities mentioned above. After matching, the numeric and graphical diagnostics were used to evaluate the improvement in the variables. Again, summary statistics were performed as described above. One-to-one comparison between the two matched groups was performed using Wilcoxon Signed Rank test for the continuous variables. The McNemar’s test was used to compare the categorical variables between the two matched groups. If the level of a categorical variable was more than two, the Stuart-Maxwell test was used. For the total hospital length stay, the Kaplan–Meier procedure was used to estimate the median time, and the standard error was estimated using the Greenwood’s formula. The log-rank test was used to compare the time (Kaplan–Meier curves) between the two groups. The 2-sided P value was reported for each test. A P value of < 0.05 was considered an indication of statistical significance. Statistical analysis was performed using the R language [13].

Results

Patients’ characteristics & Univariate analysis

Out of 491 patients who qualified for the study, 398 (81.1 %) patients underwent total abdominal colectomy. Only 93 (18.9%) patients underwent partial colectomy. Fifty one out of 93 (54.83%) patients underwent right sided colectomy and remaining 42 (45.17%) patients had left sided colectomy. Approximately 84% of patient underwent colectomy for toxic colon and approximately 16% of patients underwent colectomy for perforation. The median [IQR] age of the patient who underwent partial colectomy was 66 [55–75], the male and female distribution was almost split equally with slight increase of male dominance, ~ 53% and about 77% of patients were Caucasians. There were significant differences found between the two groups, TAC and partial colectomy groups, regarding the presence of septic shock prior to surgery (67.8% versus 52.7%, P = 0.03). TAC group presented with higher percentage of life threatening of ASA class (66.3% versus 59.1%, P = 0.029) and found to have higher percentage of patients with history of steroid use (22.9% versus 12.9%, P = 0.047). Significantly higher proportion of patients in TAC group mounted severe leukocytosis (≥ 20 × 109/L) (Table 1).

Propensity matching analysis

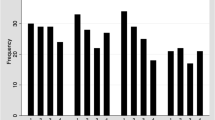

The propensity matching created 93 pairs. There was significant improvement in patients’ characteristics after the matching. The pair matched analysis showed that all the differences between the two groups found in univariate analysis were balanced after the matching. (Figure) 1.

There were no differences between the groups, TAC versus partial colectomy, regarding median age 65[57–75] vs. 66 [55–75], race [Caucasians] 73.1% vs. 77.4%, gender [male] (49.5% vs. 52.7%), septic shock prior to surgery (55.9% vs. 52.7%) and ventilator dependent respiratory failure (37.6% vs. 29%) and comorbidities, all P values were > 0.05 (Table 2).

There was no significant difference in mortality between the TAC and partial colectomy groups (30.1% vs. 30.1%, P > 0.99). The median [95% CI] hospital length of stay between the TAC and partial colectomy was (23 [19–31] vs. 21 [17–25], P = 0.30). There was no significant difference found between the groups, TAC and partial colectomy, regarding the discharged disposition to home (33.8% vs. 43.1%) or transfer to rehab (21.55 vs. 12.3%, P = 0.357) (Table 3).

There were no significance differences found between the two groups regarding surgical site infections, incidence of pneumonia, urinary tract infections, sepsis, septic shock, return to operating room, failure to wean from the ventilator and readmission rates Table 4.

Discussion

Our study showed that the majority, ~ 81% of FCDC patients underwent total abdominal colectomy while only ~ 19% of patients had partial colectomy. The all-cause 30-days mortality in the matched group was 30.1%. Partial colectomy did not show any difference in overall mortality or post-operative complications and discharge disposition to home.

Prior studies showed that early colectomy had a better survival probability than no colectomy [4, 14]. Total abdominal colectomy has been the practice pattern for many decades in fulminant cases of FCDC [5]. In 2015, World Society of Emergency Surgery (WSES) recommendation was to perform early TAC in the management of FCDC [15]. The updated WSES guidelines in 2019 kept the TAC as a primary choice of surgical intervention [16].

Very few prior studies have examined the comparison of mortality outcome of TAC with partial colectomy. A study examined the surgical mortality of the FCDC found that patients underwent partial colectomy had the worse outcome than the TAC [17]. The major limitation of the study was a very small sample size. The total number of patients included in the study was 14 and the major reasons for the high mortality in partial colectomy were not very clear. Byrn and colleagues examined 73 patients with FCDC who underwent colectomy [18]. Most colectomies (86%) were subtotal colectomy, only 4 patient had right hemicolectomy and 5 had left hemicolectomy and one patient had total colectomy. One patient who had left hemicolectomy was converted to total colectomy. No significant difference was found in overall mortality whether the patient underwent partial colectomy or subtotal colectomy (10% vs 38%, respectively; P > 0.05). A recent NSQIP database study included all patients with FCDC who underwent colectomies from 2007 through 2015 [8]. The study consisted of 733 patients and found slightly higher mortality rate in partial colectomy group when compared to TAC (37.1% vs 34.7%, P=0.58) in univariate analysis. However, multiple logistic regression analysis did not show any significant difference in mortality of partial colectomy group when compared with TAC, the odds ratio [OR] was 1.21, 95% CI 0.76 to 1.96.

Contrary to above studies, our study included relatively recent NSQIP data set and used propensity-matched analysis, which is better modality for observational study [10]. Our results showed 81% of patients underwent TAC as recommended by the WSES [16]. Approximately 19% of patients underwent partial colectomy. The reasons for lower compliance with WSES were not available. There is a possibility that in certain cases, the point of care surgeon made the decision to perform partial colectomy was based on findings observed during the operation. Patients who underwent partial colectomy showed no difference in 30 days mortality (30.1% vs. 30.1%) when compared with TAC. Our mortality was little lower than the published report [8]. The reason may be that we used the most recent dataset that may have reflected the better selection of patients to critical care management and aggressive treatment of the FCDC [19]. The other reason for lower mortality in our study could be the inclusion of all comorbidities in our propensity-matching model that can influence the post-operative mortality [20]. Our study did not find any significant difference in median hospital length of stay and 30-day post-operative complications regardless of the type of surgery was performed (TAC vs. partial colectomy). Our study added one more outcome to evaluate the discharged disposition to home and found no significant difference between the TAC vs. partial colectomy Table 3.

Limitation

The study was done from the NSQIP database; however, the database lacks the detailed information of the some of the patients’ characteristics, the timing of the contraction of the clostridium difficile colitis, progression to FCDC and the timing of the colectomy from the time of identification of the FCDC. We used the most recommended analysis method of observational study, the propensity score matching. However, that method does not take into account any unobserved or unmeasured variables that may have influenced the results.

Conclusion

The surgical mortality of FCDC remains high. Total abdominal colectomy was the procedure of choice and adapted by majority of surgeons. Partial colectomy did not increase the risk of 30 days mortality or morbidity. The discharge disposition of patients to home or rehabilitation were same regardless of the patient underwent TAC or partial colectomy.

Implications. If the disease pathology limited to one area of the colon, partial colectomy can be an alternative procedure for the FCDC patients.

Availability of data and materials

Data are available from the American College of Surgeons.

Abbreviations

- FCDC:

-

Fulminant Clostridium Difficile Colitis

- TAC:

-

The Total Abdominal Colectomy

- NSQIP:

-

The National Surgical Quality Improvement Program

- LOS:

-

Length of stay

- CI:

-

Confidence interval

- LI:

-

Loop ileostomy

- PCR:

-

Polymerase chain reaction

- EIA:

-

Enzyme immunoassays

- ASA:

-

American Society of Anesthesiologists

- DM:

-

Diabetes mellitus

- COPD:

-

Chronic obstructive pulmonary disease

- HTN:

-

Hypertension on medication

- CRF:

-

Chronic renal failure

- CRF-D:

-

Chronic renal failure on dialysis

- WSES:

-

World Society of Emergency Surgery

References

Loo VG, Poirier L, Miller MA, et al. A predominantly clonal multi-institutional outbreak of Clostridium difficile-associated diarrhea with high morbidity and mortality. N Engl J Med. 2005;353(23):2442–9.

Dallal RM, Harbrecht BG, Boujoukas AJ, Sirio CA, Farkas LM, Lee KK, Simmons RL. Fulminant Clostridium difficile: an underappreciated and increasing cause of death and complications. Ann Surg. 2002;235(3):363–72.

Ahmed N, Kuo YH. Early colectomy safes lives in toxic mega-colon due to Clostridium difficile infection. Southern Med J. 2020;113(7):345–9.

Stewart D, Hollenbeak C, Wilson M. Is colectomy for fulminant Clostridium difficile colitis life saving? A systematic review. Colorectal Dis. 2013;15:798–804.

Napolitano LM, Edmiston CE Jr. Clostridium difficile disease: diagnosis, pathogenesis, and treatment update. Surgery. 2017;162(2):325–48.

Neal M, Alverdy J, Hall D, et al. Diverting loop ileostomy and colonic lavage: an alternative to total abdominal colectomy for the treatment of severe, complicated Clostridium difficile infections. Ann Surg. 2011;254:423–9.

Fashandi AZ, Martin AN, Wang PT, Hedrick TL, Friel CM, Smith PW, Hays RA, Hallowell PT. An institutional comparison of total abdominal colectomy and diverting loop ileostomy and colonic lavage in the treatment of severe, complicated Clostridium difficile infections. Am J Surg. 2017;213(3):507–11. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.amjsurg.2016.11.036.

Peprah D, Chiu AS, Jean RA, Pei KY. Comparison of outcomes between total abdominal and partial colectomy for the management of severe, complicated Clostridium difficile infection. J Am Coll Surg. 2019;228(6):925–30. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jamcollsurg.2018.11.015.

Christl SU, Scheppach W. Metabolic consequences of total colectomy. Scand J Gastroenterol Suppl. 1997;222:20–4. https://doi.org/10.1080/00365521.1997.11720712.

Austin PC. An introduction to propensity score methods for reducing the effects of confounding in observational studies. Multivar Behav Res. 2011;46(3):399–424. https://doi.org/10.1080/00273171.2011.568786.

https://www.facs.org/quality-programs/acs-nsqip, Access date September 3, 2020

Ho DE, Imai K, King G, Stuart EA. MatchIt: nonparametric preprocessing for parametric causal inference. J Stat Softw. 2011;42(8):1–28.

R Core Team (2020). R: A language and environment for statistical computing. R Foundation for Statistical Computing, Vienna, Austria. https://www.R-project.org/.

Sailhamer EA, Carson K, Chang Y, et al. Fulminant Clostridium difficile colitis: patterns of care and predictors of mortality. Arch Surg. 2009;144(5):433–9. https://doi.org/10.1001/archsurg.2009.51.

Sartelli M, Malangoni MA, Abu-Zidan FM, et al. WSES guidelines for management of Clostridium difficile infection in surgical patients. World J Emerg Surg. 2015;10:38. https://doi.org/10.1186/s13017-015-0033-6.

Sartelli M, Di Bella S, McFarland LV, et al. 2019 update of the WSES guidelines for management of Clostridioides (Clostridium) difficile infection in surgical patients. World J Emerg Surg. 2019;14:8. https://doi.org/10.1186/s13017-019-0228-3.

Koss A, Clark MA, Sanders A, Morton D, Keighley MR, Goh J. The outcome of surgery in fulminant Clostridium difficile colitis. Colorectal Dis. 2005. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1463-1318.2005.00876.x.

Byrn JC, Maun DC, Gingold DS, Baril DT, Ozao JJ, Divino CM. Predictors of mortality after colectomy for fulminant Clostridium difficile Colitis. Arch Surg. 2008;143(2):150–4. https://doi.org/10.1001/archsurg.2007.46.

Gillies MA, Harrison EM, Pearse RM, Garrioch S, Haddow C, Smyth L, Parks R, Walsh TS, Lone NI. Intensive care utilization and outcomes after high-risk surgery in Scotland: a population-based cohort study. Br J Anaesth. 2017;118(1):123–31. https://doi.org/10.1093/bja/aew396.

Payá-Llorente C, Martínez-López E, Sebastián-Tomás JC, et al. The impact of age and comorbidity on the postoperative outcomes after emergency surgical management of complicated intra-abdominal infections. Sci Rep. 2020;10:1631. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-020-58453-1.

Acknowledgements

Elli Gourna Paleoudis, MS, PhD performed the critical reading and final editing of the manuscript.

Funding

There was no funding provided for this study.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Nasim Ahmed (NA) conceived and designed the study. NA was responsible for retrieving the study data, while Yen-Hong Kuo (Y-HK) performed the data analysis. NA & Y-HK, contributed to manuscript writing. NA designed the study, accessed the data, and contributed to the manuscript. Y-HK performed the statistical analyses and contributed to the creation of manuscript. NA & Y-HK interpreted the data. NA is also responsible for overall integrity of the study. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Consent for publication

Since the study was performed from the de-identified dataset and a retrospective study. consent from the subject were not applicable.

Competing interests

All authors declare no conflict of interest.

Additional information

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/. The Creative Commons Public Domain Dedication waiver (http://creativecommons.org/publicdomain/zero/1.0/) applies to the data made available in this article, unless otherwise stated in a credit line to the data.

About this article

Cite this article

Ahmed, N., Kuo, YH. Outcomes of total versus partial colectomy in fulminant Clostridium difficile colitis: a propensity matched analysis. World J Emerg Surg 17, 11 (2022). https://doi.org/10.1186/s13017-022-00414-2

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/s13017-022-00414-2