Abstract

Background

Small cell carcinoma of the rectum is a rare neoplasm with scant literature to guide treatment. We used the Surveillance Epidemiology and End Results (SEER) database to investigate the role of radiation therapy in the treatment of this cancer.

Methods

The SEER database (National Cancer Institute) was queried for locoregional cases of small cell rectal cancer. Years of diagnosis were limited to 1988–2010 (most recent available) to reduce variability in staging criteria or longitudinal changes in surgery and radiation techniques. Two month conditional survival was applied to minimize bias by excluding patients who did not survive long enough to receive cancer-directed therapy. Patient demographics between the RT and No_RT groups were compared using Pearson Chi-Square tests. Overall survival was compared between patients who received radiotherapy (RT, n = 43) and those who did not (No_RT, n = 28) using the Kaplan-Meier method. Multivariate Cox proportional hazards model was used to evaluate important covariates.

Results

Median survival was significantly longer for patients who received radiation compared to those who were not treated with radiation; 26 mo vs. 8 mo, respectively (log-rank P = 0.009). We also noted a higher 1-year overall survival rate for those who received radiation (71.1% vs. 37.8%). Unadjusted hazard ratio for death (HR) was 0.495 with the use of radiation (95% CI 0.286-0.858). Among surgery, radiotherapy, sex and age at diagnosis, radiation therapy was the only significant factor for overall survival with a multivariate HR for death of 0.393 (95% CI 0.206-0.750, P = 0.005).

Conclusions

Using SEER data, we have identified a significant survival advantage with the use of radiation therapy in the setting of rectal small cell carcinoma. Limitations of the SEER data apply to this study, particularly the lack of information on chemotherapy usage. Our findings strongly support the use of radiation therapy for patients with locoregional small cell rectal cancer.

Similar content being viewed by others

Background

Neuroendocrine neoplasias (NEN) arise from neural and endocrine cell types and can occur all throughout the body. NEN are broadly grouped into pulmonary and extrapulmonary primary sites and encompass a heterogeneous class of malignancies that vary widely in their clinical presentations and characteristics. The number of different iterations of NEN that arise as a function of primary site, grade and clinical presentation compounded by their relative infrequency has made clinical trial execution difficult and slowed the pace at which outcomes can be improved for the many subtypes [1-3]. Grade I/II NEN are by definition neuroendocrine tumors (NET). Some of the literature use the term NET to refer more broadly to NEN, which encompass all grades of neuroendocrine neoplasms. The more aggressive and poorly differentiated grade III neuroendrocrine carcinomas (NEC) are further subdivided into small cell carcinomas (SCC) and large cell carcinomas (LCC).

Surveillance, Epidemiology and End Results (SEER) studies examining NEN epidemiology revealed an incidence rate of 5.25 and 5.76 per 100,000 for the 2000–2004 and 2003–2007 periods, respectively [4,5]. Both of these studies note a greater than four-fold increase in the incidence of NEN for the data available since 1973, which the authors of the studies attribute to improved diagnostic capabilities and greater disease awareness. Patients with well or moderately differentiated diagnoses had median survival times of 124 and 64 months, respectively, while those diagnosed with poorly differentiated tumors (such as SCC or LCC) had a 10 month median survival time [5]. The stark difference between mortality rates of low and high grade NEN highlights the importance of establishing more accurate and consistent grading criteria to guide future treatments, distinguish between indolent and aggressive subtypes and provide meaningful prognostic information.

Extrapulmonary GI NEN as a group make up 61% of all NEN diagnoses, with the rectum being the most common site (17.7%), followed by the small intestines (17.3%) and colon (10.1%) [4]. Amongst the more aggressive and rare GI SCC, the most common site of incidence is the esophagus (53%) followed by the colon (13%), stomach (11%), gall bladder (8.4%) and rectum (7.3%) [4,6]. SCC of the rectum are aggressive and rare tumors compromising less than 1% of all GI neoplasms, with reported median survival ranging from 7 to 11 months and estimated five year survival rates of 8-15% [5,7-12]. Due to its low incidence, there is a paucity of literature to guide treatment and we are currently limited to case reports and small retrospective studies. Treatments for extrapulmonary GI SCC have been guided by extrapolating from treatment modalities used for small cell lung cancer [2,9,13]. Nonetheless, in the published literature there was tremendous variation in treatment approaches, outcomes and follow-up information. Given the scarcity of literature and rare incidence of rectal SCC, we performed a SEER database analysis to understand the potential role of radiotherapy in the treatment of this malignancy.

Methods

The SEER database (National Cancer Institute) was queried with SEER*Stat8.1.2 software for rectal small cell cancer cases. In order to exclude patients with distant metastatic disease, we restricted the search to locoregional cases by using the “SEER Historic Stage A” variable. Years of diagnosis were restricted to 1988–2010, in order to reduce bias or error due to variability in staging/grading criteria and longitudinal changes in chemotherapy, surgery or radiation treatment techniques. Radiation in the RT group was limited to external beam radiation therapy for all cases. Surgical procedures were grouped based on the extent of resection. A two month conditional survival was applied to minimize bias by excluding patients who did not survive long enough to receive cancer-directed therapy. Overall survival was compared between patients who received radiation (RT) and those who did not (No_RT) using the Kaplan-Meier method. Multivariate Cox proportional hazards statistical modeling was used to evaluate important covariates, with AJCC Stage as a stratification variable. Patient demographics between the RT and No_RT groups were compared using Pearson Chi-Square tests.

Results

The SEER database included 71 patients that fit our study criteria. This patient cohort had 43 patients treated with radiation (RT group) and 28 patients without radiation (No_RT group). There were no significant difference between the RT and No_RT groups when considering demographic factors such as sex, race and stage (Table 1 ). There were also no statistical differences between patient location, marital status and year of diagnosis (data not shown). We did note a statistically significant difference in the sequence number in which rectal SCC was diagnosed; patients in the No_RT arm had a significant portion of rectal SCC diagnoses following another malignancy. Between the two arms of the study, the RT group received surgery 32.6% of the time, while the No_RT group received surgery 50% of the time, but this was not statistically significant with a p-value of 0.142. Chemotherapy regimen was not available through the SEER database.

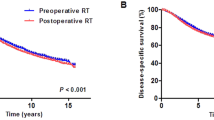

Overall survival between the two groups differed significantly, with median survival of 26 months for the RT group versus 8 months for the No_RT group (P = 0.009) (Figure 1 ). Patients who were treated with radiation had a 1 year overall survival rate of 71.1% compared to 37.8% for patients who were not treated with radiation. The unadjusted hazard ratio (HR) for death for patients that received radiation was 0.495 (95% CI 0.286-0.858). To understand how age at diagnosis, sex, surgery, and radiation affect survival, we performed univariate and multivariate cox proportional hazards modeling using AJCC stage as a stratification variable (Table 2 ). Radiation therapy was the only significant factor for overall survival, with a multivariate HR for death of 0.393 (95% CI 0.206-0.750, P = 0.005). We did not observe a significant survival benefit from the use of surgery.

Kaplan-Meier plot of rectal small cell carcinoma cases treated with or without radiation. Rectal small cell carcinoma cases stratified by radiation treatment from the SEER database were subject to Kaplan-Meier analysis for retrospective survival benefit analysis. The no radiation therapy (No_RT) arm consisted of 28 cases. The group that received radiation therapy (RT) consisted of 43 cases.

Discussion

Rectal small cell carcinoma is an aggressive and rare cancer with no standard treatment protocol. In the literature, and consistent with our own SEER analysis, the overall median survival for rectal SCC cases has ranged from 7 to 11 months [5,7-12]. Small cell lung carcinoma (SCLC) has primarily been treated with platinum based chemotherapies in conjunction with thoracic radiotherapy, and in some cases, prophylactic cranial irradiation [13-17]. However, SCLC treatments and outcomes may only go so far in translating to extrapulmonary SCC treatment. Platinum based chemotherapeutic approaches similar to those used in lung SCC have been the mainstay of treatment for many reported cases of extrapulmonary SCC [17-23]. Surgery has been used for localized disease in combination with chemotherapy or radiotherapy, but strong correlative benefits have not been established [2,9,13,23,24]. Radiotherapy used to treat extrapulmonary SCCs, with or without concurrent chemotherapy, has been reported to result in a clinical response in many cases [6,13,24-28]. Of the 12 patients who received radiotherapy for GI SCC reported by Brenner et al., 11 out of 12 saw a partial/complete response or residual disease, with a survival of 3–17 months [6]. A larger 127 patient study of limited stage esophageal SCC demonstrated a 33 month median survival for patients who received chemoradiotherapy, while those who received surgery and chemotherapy had a 17.5 month median survival [26].

We looked to the literature for rectal SCC case reports, and found a broad range of treatment strategies and patient outcomes (Table 3 ). Although some rectal SCC cases were treated with chemotherapy regimens similar to that of lung SCC, only a small portion of reported cases fell into that category. The most commonly employed treatment appeared to be surgery alone, followed by surgery and chemotherapy and lastly chemoradiotherapy. There were only three reported cases in which trimodality therapy was used. In some cases, radiotherapy was used for palliative measures in the setting of metastatic disease. The overall survival times in these case studies varied widely, and this may be partly due to differences in tumor stage at diagnosis. Although this literature search gives us a snapshot of the variety of treatment strategies on a case-by-case basis, it lacks the statistical power to guide treatment for future cases.

We cannot rule out the benefit of surgery from this study due to small sample sizes and insufficient power. It is also important to consider the limitations of using this retrospective SEER analysis to draw strong correlative conclusions. There is no chemotherapy data available in our SEER cohort, so we cannot account for any effects arising from differences in chemotherapy regimens. We were not able to determine from the SEER database whether radiation given to the RT group was with curative or palliative intent. Within our No_RT arm, a significantly greater proportion of the patients had a history of other prior malignancy before receiving a diagnosis of rectal SCC; these patients may have received previous radiation treatment to the pelvic area or previous chemotherapy. Despite the inherent limitations with using the SEER database, this study provides evidence for the benefit of radiation therapy for the treatment of rectal SCC.

Conclusions

Given the scarcity of literature, we performed an analysis of rectal SCC patients entered into the SEER database from 1988 to 2010 in the United States. We were interested in the effect of radiation therapy and surgery on overall survival in rectal SCC. Radiation has been shown to confer a benefit in other extrapulmonary SCCs and in lung SCC [6,9,13-16,26]. And, the role of surgery in extrapulmonary SCC is controversial [2,9,13,23,24]. Our analysis revealed a significant survival benefit to patients that received radiotherapy, with or without surgery. Radiation therapy was the strongest prognostic variable amongst sex, age at diagnosis or surgery for overall survival. Although this SEER analysis has limitations, such as lack of chemotherapy information and retrospective study design, it provides guidance on how to manage this rare and aggressive cancer. These findings may also influence future prospective studies to establish a standard treatment regimen for rectal SCC.

References

Klimstra DS, Modlin IR, Coppola D, Lloyd RV, Suster S. The pathologic classification of neuroendocrine tumors: a review of nomenclature, grading, and staging systems. Pancreas. 2010;39(6):707–12. doi:10.1097/MPA.0b013e3181ec124e. PubMed.

Smith J, Reidy-Lagunes D. The management of extrapulmonary poorly differentiated (high-grade) neuroendocrine carcinomas. Semin Oncol. 2013;40(1):100–8. doi: 10.1053/j.seminoncol.2012.11.011. PubMed.

Modlin IM, Oberg K, Chung DC, Jensen RT, de Herder WW, Thakker RV, et al. Gastroenteropancreatic neuroendocrine tumours. Lancet Oncol. 2008;9(1):61–72. doi:10.1016/S1470-2045(07)70410-2. PubMed.

Lawrence B, Gustafsson BI, Chan A, Svejda B, Kidd M, Modlin IM. The epidemiology of gastroenteropancreatic neuroendocrine tumors. Endocrinol Metab Clin North Am. 2011;40(1):1–18. doi:10.1016/j.ecl.2010.12.005. PubMed.

Yao JC, Hassan M, Phan A, Dagohoy C, Leary C, Mares JE, et al. One hundred years after “carcinoid”: epidemiology of and prognostic factors for neuroendocrine tumors in 35,825 cases in the United States. J Clin Oncol. 2008;26(18):3063–72. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2007.15.4377. PubMed.

Brenner B, Tang LH, Klimstra DS, Kelsen DP. Small-cell carcinomas of the gastrointestinal tract: a review. J Clin Oncol. 2004;22(13):2730–9. doi:10.1200/JCO.2004.09.075. PubMed.

Robidoux A, Monte M, Heppell J, Schurch W. Small-cell carcinoma of the rectum. Dis Colon Rectum. 1985;28(8):594–6. PubMed.

Clery AP, Dockerty MB, Waugh JM. Small-cell carcinoma of the colon and rectum. A clinicopathologic study. Arch Surg. 1961;83:164–72. PubMed.

Brenner B, Shah MA, Gonen M, Klimstra DS, Shia J, Kelsen DP. Small-cell carcinoma of the gastrointestinal tract: a retrospective study of 64 cases. Br J Cancer. 2004;90(9):1720–6. doi:10.1038/sj.bjc.6601758. PubMed PMID: 15150595; PubMed Central PMCID: PMC2409752.

Bernick PE, Klimstra DS, Shia J, Minsky B, Saltz L, Shi W, et al. Neuroendocrine carcinomas of the colon and rectum. Dis Colon Rectum. 2004;47(2):163–9. PubMed.

Strosberg J, Nasir A, Coppola D, Wick M, Kvols L. Correlation between grade and prognosis in metastatic gastroenteropancreatic neuroendocrine tumors. Hum Pathol. 2009;40(9):1262–8. doi: 10.1016/j.humpath.2009.01.010. PubMed.

Staren ED, Gould VE, Warren WH, Wool NL, Bines S, Baker J, et al. Neuroendocrine carcinomas of the colon and rectum: a clinicopathologic evaluation. Surgery. 1988;104(6):1080–9. PubMed.

Walenkamp AM, Sonke GS, Sleijfer DT. Clinical and therapeutic aspects of extrapulmonary small cell carcinoma. Cancer Treat Rev. 2009;35(3):228–36. doi: 10.1016/j.ctrv.2008.10.007. PubMed.

Califano R, Abidin AZ, Peck R, Faivre-Finn C, Lorigan P. Management of small cell lung cancer: recent developments for optimal care. Drugs. 2012;72(4):471–90. doi:10.2165/11597640-000000000-00000. PubMed.

Kallianos A, Rapti A, Zarogoulidis P, Tsakiridis K, Mpakas A, Katsikogiannis N, et al. Therapeutic procedure in small cell lung cancer. J Thorac Dis. 2013;5 Suppl 4:S420–4. doi: 10.3978/j.issn.2072-1439.2013.09.16. PubMed PMID: 24102016; PubMed Central PMCID: PMC3791494.

Turrisi 3rd AT, Kim K, Blum R, Sause WT, Livingston RB, Komaki R, et al. Twice-daily compared with once-daily thoracic radiotherapy in limited small-cell lung cancer treated concurrently with cisplatin and etoposide. N Engl J Med. 1999;340(4):265–71. doi:10.1056/NEJM199901283400403. PubMed.

Spiliopoulou P, Panwar U, Davidson N. Rectal small cell carcinoma: a case report and review of the literature. Case Rep Oncol. 2011;4(3):475–80. doi:10.1159/000332760. PubMed PMID: 22114573; PubMed Central PMCID: PMC3220900.

Okuyama T, Korenaga D, Tamura S, Yao T, Maekawa S, Watanabe A, et al. The effectiveness of chemotherapy with cisplatin and 5-fluorouracil for recurrent small cell neuroendocrine carcinoma of the rectum: report of a case. Surg Today. 1999;29(2):165–9. PubMed.

Joshua AM, Adams D, McKenzie P, Solomon M, Clarke SJ. Small blue cell tumors of the rectum. Case 2. Small-cell carcinoma of the rectum. J Clin Oncol. 2005;23(4):912–3. doi:10.1200/JCO.2005.03.094. PubMed.

Ihtiyar E, Algin C, Isiksoy S, Ates E. Small cell carcinoma of rectum: a case report. World J Gastroenterol. 2005;11(20):3156–8. PubMed.

Cebrian J, Larach SW, Ferrara A, Williamson PR, Trevisani MF, Lujan HJ, et al. Small-cell carcinoma of the rectum: report of two cases. Dis Colon Rectum. 1999;42(2):274–7. PubMed.

Gupta S, Engstrom PF, Cohen SJ. Emerging therapies for advanced gastroenteropancreatic neuroendocrine tumors. Clin Colorectal Cancer. 2011;10(4):298–309. doi:10.1016/j.clcc.2011.06.006. PubMed.

Sarsfield P, Anthony PP. Small cell undifferentiated (‘neuroendocrine’) carcinoma of the colon. Histopathology. 1990;16(4):357–63. PubMed.

Brenner B, Tang LH, Shia J, Klimstra DS, Kelsen DP. Small cell carcinomas of the gastrointestinal tract: clinicopathological features and treatment approach. Semin Oncol. 2007;34(1):43–50. doi:10.1053/j.seminoncol.2006.10.022. PubMed.

Medgyesy CD, Wolff RA, Putnam Jr JB, Ajani JA. Small cell carcinoma of the esophagus: the University of Texas M. D. Anderson Cancer Center experience and literature review. Cancer. 2000;88(2):262–7. PubMed.

Meng MB, Zaorsky NG, Jiang C, Tian LJ, Wang HH, Liu CL, et al. Radiotherapy and chemotherapy are associated with improved outcomes over surgery and chemotherapy in the management of limited-stage small cell esophageal carcinoma. Radiother Oncol. 2013;106(3):317–22. doi:10.1016/j.radonc.2013.01.008. PubMed.

Huncharek M, Muscat J. Small cell carcinoma of the esophagus. The Massachusetts General Hospital experience, 1978 to 1993. Chest. 1995;107(1):179–81. PubMed.

Matsui K, Kitagawa M, Miwa A, Kuroda Y, Tsuji M. Small cell carcinoma of the stomach: a clinicopathologic study of 17 cases. Am J Gastroenterol. 1991;86(9):1167–75. PubMed.

Sato Y, Fujisawa J, Saji Y, Misawa K, Yabuki H, Kotani H, et al. [A case of small cell undifferentiated carcinoma (SCUC) of the rectum treated with etoposide, cis-platinum and radiotherapy]. Gan To Kagaku Ryoho. 1992;19(13):2245–9. PubMed.

Kosmidis C, Efthimiadis C, Anthimidis G, Vasiliadou K, Tzeveleki I, Fotiadis P, et al. Small cell carcinoma in ulcerative colitis–new treatment option: a case report. World J Surg Oncol. 2010;8:100. doi:10.1186/1477-7819-8-100. PubMed PMID: 21087512; PubMed Central PMCID: PMC2999595.

Vergeli-Rojas JA, Santiago-Caraballo DL, Caceres-Perkins W, Magno-Pagatzartundua P, Toro DH, et al. Small cell neuroendocrine carcinoma of rectum with associated paraneoplastic syndrome: a case report. P R Health Sci J. 2013;32(1):51–3. PubMed.

Khansur TK, Routh A, Mihas TA, Underwood JA, Smith GF, Mihas AA, et al. Syndrome of inappropriate ADH secretion and diplopia: oat cell (small cell) rectal carcinoma metastatic to the central nervous system. Am J Gastroenterol. 1995;90(7):1173–4. PubMed.

Ree AH. A complex case of rectal neuroendocrine carcinoma with terminal delirium. Nat Clin Pract Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2006;3(7):408–13. doi:10.1038/ncpgasthep0525. PubMed. quiz 14.

Yaziji H, Broghamer Jr WL. Primary small cell undifferentiated carcinoma of the rectum associated with ulcerative colitis. South Med J. 1996;89(9):921–4. PubMed.

Gaffey MJ, Mills SE, Lack EE. Neuroendocrine carcinoma of the colon and rectum. A clinicopathologic, ultrastructural, and immunohistochemical study of 24 cases. Am J Surg Pathol. 1990;14((11):1010–23. PubMed.

Sakamoto Y, Kitajima Y, Ogawa A, Hidaka K, Miyazaki K. [Successful combination chemotherapy for a case of small cell carcinoma of the rectum with multiple liver metastasis]. Gan To Kagaku Ryoho. 1999;26(4):543–7. PubMed.

Hayashi H, Miyagi Y, Sekiyama A, Yoshida S, Nakao S, Okamoto N, et al. Colorectal small cell carcinoma in ulcerative colitis with identical rare p53 gene mutation to associated adenocarcinoma and dysplasia. J Crohns Colitis. 2012;6(1):112–5. doi: 10.1016/j.crohns.2011.08.009. PubMed.

Al-Jiffry BO, Al-Malki O. Neuroendocrine small cell rectal cancer metastasizing to the liver: a unique treatment strategy, case report, and review of the literature. World J Surg Oncol. 2013;11:153. doi:10.1186/1477-7819-11-153. PubMed PMID: 23844568; PubMed Central PMCID: PMC3717129.

Kuratate S, Inoue S, Chikakiyo M, Kaneda Y, Harino Y, Hirose T, et al. Coexistent poorly-differentiated neuroendocrine cell carcinoma and non-invasive well-differentiated adenocarcinoma in tubulovillous adenoma of the rectum: report of a case. J Med Invest. 2010;57(3–4):338–44. PubMed.

Wu Y, Wang Q, Wang L, He X. Extrapulmonary Small Cell Carcinoma of the Rectum. Journal of gastrointestinal cancer. 2012. doi:10.1007/s12029-012-9418-x. PubMed

Sato K, Yokouchi Y, Saida Y, Ito S, Kitagawa T, Maetani I. A small cell neuroendocrine carcinoma of the rectum diagnosed by colorectal endoscopic submucosal dissection. J Gastrointestin Liver Dis. 2012;21(2):128. PubMed.

Izuishi K, Arai T, Ochiai A, Ono M, Sugito M, Tajiri H, et al. Long-term survival in advanced small cell carcinoma of the colorectum: report of a case. Surg Today. 2002;32(1):72–4. PubMed.

Molas G, Bougis-de-Brux MA, Potet F. [Small-cell anaplastic neuroendocrine carcinoma of the rectum]. Gastroenterol Clin Biol. 1987;11(12):904–7. PubMed.

Shirouzu K, Morodomi T, Isomoto H, Ono S, Kakegawa T, Yasuaki F, et al. Long term survival case of small (oat) cell carcinoma of the rectum. Acta Pathol Jpn. 1987;37(1):111–6. PubMed.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Additional information

Competing interests

The authors declared that they have no competing interests.

Authors’ contributions

ASM, HCH and CGL participated in data acquisition and literature review. Statistical analysis was performed by HCH. KLD and HCH conceived of the study. All authors assisted in preparing the manuscript. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Rights and permissions

This article is published under an open access license. Please check the 'Copyright Information' section either on this page or in the PDF for details of this license and what re-use is permitted. If your intended use exceeds what is permitted by the license or if you are unable to locate the licence and re-use information, please contact the Rights and Permissions team.

About this article

Cite this article

Modrek, A.S., Hsu, H.C., Leichman, C.G. et al. Radiation therapy improves survival in rectal small cell cancer - Analysis of Surveillance Epidemiology and End Results (SEER) data. Radiat Oncol 10, 101 (2015). https://doi.org/10.1186/s13014-015-0411-y

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/s13014-015-0411-y