Abstract

Background

To validate a gradient-based segmentation method for gross tumor volume(GTV) delineation on 8F-fluorothymidine (FLT)positron emission tomography (PET)/ computer tomography (CT) in esophageal squamous cell cancer through pathologic specimen, in comparison with standardized uptake values (SUV) threshold-based methods and CT. The corresponding impact of this GTV delineation method on treatment planning was evaluated.

Methods and materials

Ten patients with esophageal squamous cell cancer were enrolled. Before radical surgery, all patients underwent FLT-PET/CT. GTVs were delineated by using four methods. GTVGRAD, GTV1.4 and GTV30%max were segmented on FLT PET using a gradient-based method, a fixed threshold of 1.4 SUV and 30% of SUVmax, respectively. GTVCT was based on CT data alone. The maximum longitudinal tumor length of each segmented GTV was compared with the measured tumor length of the pathologic gross tumor length (LPath). GTVGRAD, GTV1.4 and GTV30%max were compared with GTVCT by overlap index. Two radiotherapy plannings (planGRAD) and (planCT) were designed for each patient based on GTVGRAD and GTVCT. The dose-volume parameters for target volume and normal tissues, CI and HI of planGRAD and planCT were compared.

Results

The mean ± standard deviation of LPath was 6.47 ± 2.70 cm. The mean ± standard deviation of LGRAD,L1.4, L30%max and LCT were 6.22 ± 2.61, 6.23 ± 2.80, 5.95 ± 2.50,7.17 ± 2.28 cm, respectively. The Pearson correlation coefficients between LPath and each segmentation method were 0.989, 0.920, 0.920 and 0.862, respectively. The overlap indices of GTVGRAD, GTV1.4, GTV30%max when compared with GTVCT were 0.75 ± 0.12, 0.71 ± 0.12, 0.57 ± 0.10, respectively. The V5, V10, V20, V30 and mean dose of total-lung,V30 and mean dose of heart of planGRAD were significantly lower than planCT.

Conclusions

The gradient-based method provided the closest estimation of target length. The radiotherapy plannings based on the gradient-based segmentation method reduced the irradiated volume of lung, heart in comparison to CT.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Radiotherapy (RT) is one of the most important treatment modalities for esophageal cancer. CT has been the standard of GTV delineationn in esophageal cancer, however, there is growing interest in using PET-guided GTV delineation [1] to take advantage of increased contrast between tumor and surrounding normal tissue.

18F-fluorodeoxyglucose (FDG) is the most frequently used radiopharmaceutical for oncologic PET scanning. However, FDG-PET has limitations in specificity. False-positive results can be caused by inflammation, including peritumoural inflammatory reactions [2]. Studies have shown that FLT is a good imaging tracer for cell proliferation [3-6] and tumor volume change [7]. However, little data is available on the clinical use of FLT-PET in various carcinomas [8-10], including esophageal cancer.

A number of methods have been used for GTV delineation in PET including manual contouring [11,12] and semi-automatic threshold-based segmentation [13,14]. However, these methods have inherent limitations. To overcome these limitations gradient-based segmentation method has been developed to identify the tumor based on changes in count levels at the tumor border. This method has been validated using phantoms [15,16] and through comparison to pathologic specimens for head and neck carcinoma [15] and non-small-cell lung cancer (NSCLC) [17]. However, data for GTV delineation in esophageal cancer using gradient-based segmentation is lacking and in particular using FLT-PET. Our goal in this current study was to validate a gradient-based segmentation method for GTV delineation in esophageal cancer through pathologic specimens in comparison with SUV thresholds and CT. The impact of using the gradient-based delineated GTV in comparison to the CT delineated GTV was evaluated using dose volume parameters of the lung, heart, and spinal cord.

Methods and materials

Patients selection

Ten patients (mean age 60 years, range 52-75) with histologically proven esophageal squamous cell carcinoma were prospectively enrolled in this study between September 2008 and January 2009. Four patients had middle thoracic esophageal cancer, and six had lower thoracic disease. None of the patients had previously been treated with preoperative chemotherapy or RT. First, all patients underwent routine pretreatment evaluation, including physical examination, complete blood count, biochemistry surveys of liver and kidney function, chest radiographs, electrocardiograms, barium esophagograms, esophagogastroscopy with tumor biopsy, ultrasound evaluation of the neck and abdomen, and pulmonary function testing. Informed consent was obtained from all patients.

Image acquisition

FLT-PET/CT image acquisitions were performed within 4 days prior to surgical tumor resection with a dedicated PET/CT scanner (Discovery LS, GE Healthcare). The patients fasted for at least 6 hours and rested for 15 minutes before the injection of 300–400 MBq of FLT. Images were obtained 60 min after injection. The scans were performed for 5 min/ bed position from head to femur, each covering 14.5 cm, at an axial sampling thickness of 4.25 mm/slice. Both PET and CT acquisition were performed in free respiration. Data were reconstructed using an iterative reconstruction technique and attenuation correction derived from CT data. The CT,PET and fused PET/CT images were transmitted to MIM Maestro (MIM Software Inc, Cleveland, OH) for GTV delineation.

Delineation of GTV

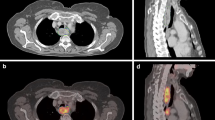

For each patient, four different GTVs were generated (Figure 1). The PET/CT images were reviewed by one experienced nuclear medicine physician and a radiation oncologist, GTVGRAD, GTV1.4 and GTV30%max were automatically segmented on PET images using the gradient-based method, fixed threshold values at 1.4 SUV and 30% of SUVmax. The longitudinal gross tumor length of GTVGRAD, GTV1.4 and GTV30%max, were recorded as LGRAD, L1.4 and L30%max, respectively. One experienced radiologist and one radiation oncologist, both unaware of the results from PET or surgery, segmented the CT images (GTVCT), using esophageal wall thickness of 5 mm or more and esophageal wall diameter without gas more than 10mm as the criteria of primary tumor. The longitudinal gross tumor length of CT was measured and recorded as LCT. Figure 1 shows case that overview of the tumor delineated by different methods. The 1.4 SUV threshold was chosen based on a previous study [7] and the 30% of SUVmax was based on clinical experience. The method for gradient-based segmentation has been previously described. “It calculates spatial derivatives along the tumor radii and then defines the tumor edge on the basis of derivative levels and continuity of the tumor edge. The software relies on an operator- defined starting point near the center of the lesion. As the operator drags out from the center of the lesion, 6 axes extend out, providing visual feedback for the starting point of gradient segmentation. Spatial gradients are calculated along each axis interactively, and the length of an axis is restricted when a large spatial gradient is detected along that axis. The 6 axes define an ellipsoid that is then used as an initial bounding region for gradient detection [16]”. The fixed SUV threshold methods involved placing a user-defined sphere over the tumor and applying the threshold inside of the sphere to segment the tumor.

Overview of the tumor delineation for one patient with middle thoracic esophageal cancer. (A) Gross tumor lengths delineated on CT images by different methods. (B) Gross tumor lengths delineated on FLT PET/CT images by different methods. Volumes are displayed in transaxial, sagittal and coronal planes. Purple, orange, blue and Red contours illustrate different parameters (e.g. GRAD, 1.4 SUV threshold, 30% of SUVmax and CT).

Processing of the surgical specimen

All patients underwent transthoracic esophagectomy with conventional two-or three-field lymphadenectomy. The specimens were flattened within 30 min after surgical resection, stretched to same length as measured in-situ, pinned on a plastic foam-board, then soaked and fixed with 10% formaldehyde. The specimens were cut into 5mm-wide strips of tissue following longest dimension of the tumor (including upper and lower margin)to create the pathological sections [7]. LPath is defined as the pathological gross tumor length as measured under a low magnification microscope.

GTV data analysis

The longitudinal gross tumor length and volumes of GTVs derived from different delineation methods were compared.

The mean and standard deviation of longitudinal gross tumor length for each of the segmentation method was calculated. LGRAD, L1.4 and L30%max were compared with LPath by means of the correction coefficients. The Lpath were defined as the “gold standard,” but because the correction coefficient does not allow preference between GTVPET and GTVCT, an overlap index (OI) was also calculated for each set of contours according to the expression:

The OI reflects the inclusion of GTVPET within GTVCT [18].

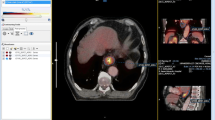

Treatment planning design and evaluation

Both PET and CT data for all patients were transmitted to a Pinnacle3 treatment planning station (Philips, 8.0 m). The clinical target volume (CTV) was created using a 3 cm margin in the craniocaudal direction (following the course of the esophagus) and a 1 cm margin in the lateral and anteroposterior directions beyond GTVGRAD and GTVCT. The CTV was then expanded in all directions by 0.5 cm to create the planning target volume (PTV): PTVGRAD and PTVCT. Two treatment plannings, planGRAD and planCT were designed based on PTVGRAD and PTVCT, respectively. The radiation dose was prescribed as 60Gy in 30 fractions using a five-beam conformal radiotherapy treatment. The treatment plannings of a 67-years-old female patient with middle thoracic esophageal cancer were showed in Figure 2. The plans were designed to meet the following treatment planning goals: >95% of the PTV covered by the prescription isodose line, V20 of total lung < 30%, V40 of heart < 30% and Dmax of spinal cord < 45 Gy.It was required that there was no cold spot in the PTV and no hot spot in esophageal wall. Cumulative DVHs were generated for evaluation and comparison of planGRAD and planCT. For PTV, the values of HI (heterogeneity index) and CI (conformal index) were compared. The mean lung dose (MLD), V5 (volume included by 5Gy isodose curve), V10, V20, V30 and mean lung dose of total lung, V30 (volume included by 30Gy isodose curve), V40, mean heart dose (MHD) of heart and maximum dose of spinal cord (Dmax) were recorded.

Statistical analysis

The Statistical Package for Social Sciences, version 13.0 (SPSS, Chicago, IL) was used for statistical analysis. The two-tailed paired Student’s t-test was applied to assess the differences between groups and Pearson’s correlation were performed to assess the relationship between groups. A p value of <0.05 was considered statistically significant. HI = (D2-D98)/prescription dose * 100% [19]; and CI = Vt,ref/Vt * Vt,ref/Vref [20]. [Note: Vt = target volume, Vt,ref = target volume wrapped by reference isodose, Vref = all volume wrapped by reference isodose]. CI values range beetween 0 and 1 with a value closer to 1 represents a better conformity.

Results

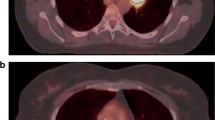

The mean of LPath was (6.47 ± 2.7) cm (range, 3.44-11.00 cm). Of the 10 primary cancers, 4 were >5 cm and 6 were <5 cm. The mean length obtained using each segmentation method was depicted in Figure 3. The correlation coefficients of LGRAD, L1.4, L30%max, LCT with LPath were 0.989 (P < 0.05), 0.920 (P < 0.05), 0.920 (P < 0.05), 0.862 (P < 0.05), respetively. In comparison to the PET determined GTV, LCT led to a large over estimation of LPath. LGRAD seemed to more greatly approximate to LPath.

The mean volume of GTVCT was (38.37 ± 30.04) cm3 (range: 14.41-105.11 cm3),the mean volume obtained using each segmentation method was depicted in Figure 4. The GTVs generated from FLT PET/CT were significantly smaller than GTVCT (P < 0.05). The mean OI of GTVGRAD, GTV1.4 and GTV30%max with GTVCT were 0.75 ± 0.12, 0.71 ± 0.12 and 0.50 ± 0.10, the OI of GTVGRAD with GTVCT was higher than GTV1.4, but the difference between GTVGRAD and GTV1.4 was not significant.

Next, two RT simulation plannings using gradient-based segmentation method on FLT PET/CT and CT delineating target volumes in the Philips Pinnacle3 treatment planning system were compared. All the treatment plannings met the criteria that >95% of the PTV were covered by the prescription isodose line and the global hotspot was <10%. In Tables 1 and 2 the evaluation factors of PTVGRAD and PTVCT were listed. The difference in CI, HI, V40 of heart and Dmax of spinal cord between planGRAD and planCT were not significantly different. However, the V5,V10,V20, V30 and mean dose of total-lung, V30 and mean dose of heart of planGRAD were significantly lower than planCT.

Discussion

The developments of functional imaging techniques such as PET/CT have brought biologically-guided IMRT to the forefront of radiotherapy. Biologically-guided intensity-modulated radiation therapy (IMRT) has shown the advantages over traditional anatomically-based IMRT, in terms of GTV contouring, treatment planning optimization, and prognosis determination [21]. PET has been shown to supplement the information lacking in anatomical images and improves the accuracy of target volume segmentation [22]. FDG-PET image has shown the capability to accurately determine the length of esophageal tumors and GTV delineation more accurate, and improving treatment planning compared to anatomical imaging [23]. While FDG-PET has long been the most used tracer for biologic tumor imaging, in recent years, FLT has garnered attention due to its ability to characterize tumor proliferation.

In our study, we evaluated the accuracy of a gradient-based segmentation method for GTV delineation with FLT-PET using pathologically determined EC length as the gold standard. SUV threshold methods and CT visual delineation were used for comparison. Additionally we explored the feasibility of the use of FLT-PET with gradient-based segmentation for treatment planning. While all segmentation methods were found to correlate well with LPath, the gradient-based results were the most consistent with the pathologic results. Werner-Wasik M et al [16] demonstrated similar results for their gradient-based segmentation method when they found their method was more accurate than SUV thresholds and CT visual delineation for NSCLC when compared to a volumetric pathology gold standard.

Common methods of GTV segmentation for PET/CT images included visual judgement and SUV thresholds. Visual judgement relies solely on the visual discrimination of tumor boundaries, which is subjective and leads to inter observer bias. In addition, differences in window and level contrast settings contribute to variability [22]. Threshold methods often use a fixed SUV or a certain percentage of the maximum SUV as the threshold [23]. These methods are limited with regard to variations in tumor size which affect image count levels due to partial volume effects, variable tumor to background activity, and heterogeneous tracer uptake in the tumor. Gradient-based methods use the maximum spatial gradient to detect boundaries between lesions and normal tissue [24], which is not affected by different imaging equipments, reconstruction algorithms and sphere diameter effects [16]. It overcomes the limitations of visual judgement and SUV threshold methods.

The gradient and 1.4 SUV threshold methods had tumor lengths that were the most closely related to pathologically determined tumor lengths acquisition, and reconstruction variables that can significantly affect SUV measurements in typical less controlled clinical situations [1]. These factors would also impact the size of lesions detected with the absolute 1.4 SUV threshold, but do not affect the gradient –based measurement of lesion size which is based on detecting the maximum change in SUV levels regardless of their absolute value.

The CT segmentation result was found to overestimate the tumor length compared to pathology. This coincides with the results of Konski et al. [25], in which 25 esophageal cancer patients were scanned using CT and PET/CT. In their study the PET/CT scans showed a mean tumor length of 5.4 cm compared to 6.77 cm from CT, representing a statistically significant difference.

The CT-based contours also were found to be larger in size than the gradient-based contours, which may be due to the fact that the entirety of the esophageal wall is typically included in the CT-defined GTV, regardless of which part of the wall the tumor is in. Since the target volume shown in FLT-PET images represents FLT uptake activity, it could include the entire esophageal wall or just part of the wall. In addition, inflammation will show a thickened esophageal wall in CT images, whereas this may not affect the uptake activity shown in FLT PET images.

3DCRT plans using PTVGRAD and PTVCT were designed to compare dosimetric differences between treatment plannings using target volumes delineated with gradient-based and CT-based methods respectively. As shown, GTVGRAD was smaller in volume than GTVCT, and the outer borders caused even greater differences in PTV volume, which has a direct impact on the dose given to normal tissue. While conformality and homogeneity of the two groups of PTVs were similar, planGRAD resulted in significantly lower organ at risk doses than planCT. To some extent, this would reduce the side effects of radiotherapy, thereby improving patient quality of life and prognosis. However, it has also been reported in the literature that FLT PET/CT will miss some small primary tumors [26], so a variety of imaging modalities should be combined with caution in clinical practice.

The major limitation of our study is that the GTV information on the specimens was not obtained due to some technical reasons. The esophagus is an organ composed of musculature and lumen; the esophageal specimen will contract and deform after being resected, including the tumor [27]. Therefore, the volume measured on a specimen may not reflect their real values in situ. We measured the length of the specimen in situ and pinned the specimen to a flat board before fixing it with 10% formaldehyde, hoping this method would be less influenced by the deformation of esophageal lumen and thus provide an approximate estimation. Another limitation of the present study was the limited number of patients, to evaluate whether the integration of FLT PET/CT into radiotherapy of esophageal cancer can actually improve the treatment outcomes, a larger sample prospective investigation with data of treatment failures after radiotherapy planning based on PET/CT is worthy of expectation.

Conclusions

Gradient-based segmentation provides a more precise method for esophageal cancer delineating than SUV thresholds or CT visual delineation using FLT-PET/CT, laying the foundation for future development in FLT-PET/CT and BTV-based treatment planning of esophageal cancer. Further research needs to be done to validate this work using larger sample sizes and assessing the clinical impact of treatment plannings designed using gradient-defined biologic tumor volumes.

Abbreviations

- RT:

-

Radiotherapy

- GTV:

-

Gross target volume

- CTV:

-

Clinical target volume

- PTV:

-

Planning target volume

- PET:

-

Positron emission tomography

- CT:

-

Computer tomography

- FDG:

-

18F-fluorodeoxyglucose

- FLT:

-

18F-fluorothymidine

- NSCLC:

-

Non-small-cell lung cancer

- IMRT:

-

Intensity-modulated radiation therapy

- SUV:

-

Standardized uptake values

- OI:

-

Overlap index

- MLD:

-

Mean lung dose

- CI:

-

Conformal index

- HI:

-

Heterogeneity index

References

Hatt M, Visvikis D, Albarghach NM, Tixier F, Pradier O, Cheze-le Rest C. Prognostic value of 18F-FDG PET image-based parameters in oesophageal cancer and impact of tumor delineation methodology. Eur J Nucl Med Mol Imaging. 2011;38:1191–202.

Janssen MH, Ollers MC, Riedl RG, van den Bogaard J, Buijsen J, van Stiphout RG, et al. Accurate prediction of pathological rectal tumor response after two weeks of preoperative radiochemotherapy using 18F-fluorodeoxyglucose-positron emission tomography-computed tomography imaging. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys. 2010;77:392–9.

Vesselle H, Grierson J, Muzi M, Pugsley JM, Schmidt RA, Rabinowitz P, et al. In vivo validationof 3′deoxy-3′-[18F] fluorothymidine ([18F]FLT) as a proliferation imaging tracer in humans: correlation of [18F]FLT uptake by positron emission tomography with Ki-67 immunohisto- chemistry and flow cytometry in human lung tumors. Clin Cancer Res. 2002;8:3315–32.

Buck AK, Hetzel M, Schirrmeister H, Halter G, Möller P, Kratochwil C, et al. Clinical relevance of imaging proliferative activity in lung nodules. Eur J NuclMed Mol Imaging. 2005;32:525–33.

Yap CS, Czernin J, Fishbein MC, Cameron RB, Schiepers C, Phelps ME, et al. Evaluation of thoracic tumors with18F-Fluorothymidine and18F-Fluorodeoxyglucose-positron emissiontomography. Chest. 2006;129:393–401.

Dittmann H, Dohmen BM, Paulsen F, Eichhorn K, Eschmann SM, Horger M, et al. 18F-FLT PET for diagnosis and staging of thoracic tumours. Eur J NuclMed Mol Imaging. 2003;30:1407–12.

Han D, Yu J, Yu Y, Zhang G, Zhong X, Lu J, et al. Compasion of 18F-fluorthymidine and 18F-fluorodeoxy -glucose PET/CT in delineating gross tumor by optimal volume by optimal threshold in patients with squamous carcinoma of thoracic esophagus. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys. 2010;76:1235–41.

Cobben DC, van der Laan BF, Maas B, Vaalburg W, Suurmeijer AJ, Hoekstra HJ, et al. 18F-FLT PET for visualizationof laryngeal cancer: comparisonwith18F-FDG PET. J Nucl Med. 2004;45:226–31.

Smyczek-Gargya B, Fersis N, Dittmann H, Vogel U, Reischl G, Machulla HJ, et al. PET with [18F]fluorothymidine for imaging of primary breastcancer:a pilot study. Eur J Nucl Med Mol Imaging. 2004;31:720–4.

Van Westreenen HL, Cobben DC, Jager PL, van Dullemen HM, Wesseling J, Elsinga PH, et al. Comparison of 18F-FLT PET and 18F-FDG PET in esophageal cancer. J Nucl Med. 2005;46:400–4.

Hanna GG, Carson KJ, Lynch T, McAleese J, Cosgrove VP, Eakin RL, et al. 18F-fluorodeoxy glucose positron emission tomography/computed tomography-based radiotherapy target volume definition in non-small-cell lung cancer: delineation by radiation oncologists vs. joint outlining with a PET radiologist? Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys. 2010;78:1040–51.

Schinagl DA, Vogel WV, Hoffmann AL, van Dalen JA, Oyen WJ, Kaanders JH. Comparison of five segmentation tools for 18F-fluoro-deoxy-glucose-positron emission tomography-based target volume definition in head and neck cancer. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys. 2007;69:1282–9.

Grills IS, Yan D, Black QC, Wong CY, Martinez AA, Kestin LL. Clinical implications of defining the gross tumor volume with combination of CT and18FDG-positron emission tomography in non-small-cell lung cancer. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys. 2007;67:709–19.

Deniaud-Alexandre E, Touboul E, Lerouge D, et al. Impact of computed tomography and18F-deoxyglucose coincidence detection emission tomography image fusion for optimization of conformal radiotherapy innon-small-cell lung cancer. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys. 2005;63:1432–41.

Geets X, Lee JA, Bol A, Lonneux M. A gradient-based method for segmenting FDG-PET images: methodology and validation. Eur J Nucl Med Mol Imaging. 2007;34:1427–38.

Werner-Wasik M, Nelson AD, Choi W, Arai Y, Faulhaber PF, Kang P, et al. What is the best way to contour lung tumors on PET scans? Multiobserver validation of a gradient-based method using a NSCLC digital PET phantom. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys. 2012;82:1164–71.

Fogh S, Karancke J, Nelson AS, McCue P, Axelrod R, Werner-Wasik W. Pathologic Correlation of PET-CT Based Auto-contouring for Radiation Planning in Lung Cancer. World Conference on Lung Cancer Meeting. 2009.

Tsuji SY, Hwang A, Weinberg V, Yom SS, Quivey JM, Xia P. Dosimetric evaluation of automatic segmentation for adaptive IMRT for head-and-neck cancer. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys. 2010;77:707–14.

Wu Q, Mohan R, Morris M, Lauve A, Schmidt-Ullrich R. Simultaneous integrated boost intensity-modulated radiotherapy for locally advanced head-and-neck squamous cell carcinomas. I: dosimetric results. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys. 2003;56:573–85.

Baltas D, Kolotas C, Geramani K, Mould RF, Ioannidis G, Kekchidi M, et al. A conformal index (COIN) to evaluate implant quality and dose specification in brachytherapy. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys. 1998;40:515–24.

MacManus M, Nestle U, Rosenzweig KE, Carrio I, Messa C, Belohlavek O, et al. Use of PET and PET/CT for radiation therapy planning: IAEA expert report 2006-2007. Radiother Oncol. 2009;91:85–94.

Yu W, Fu XL, Zhang YJ, Xiang JQ, Shen L, Jiang GL, et al. GTV spatial conformity between different delineation methods by 18FDG PET/CT and pathology in esophageal cancer. Radiother Oncol. 2009;93:441–6.

Zhong XJ, Yu JM, Zhang BJ, Mu D, Zhang W, Li D, et al. Using 18F-fluorodeoxyglucose positron emission tomography to estimate the length of gross tumor in patients with squamous cell carcinoma of the esophagus. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys. 2009;73:136–41.

Shen G, Nelson D, Adler L. PET tumor segmentation: comparison of gradient-based algorithm to constant threshold algorithm. Med Phys. 2007;34:2395.

Konski A, Doss M, Milestone B, Haluszka O, Hanlon A, Freedman G, et al. The integration of 18-fluorodeoxyglucose positron emission tomography and endoscopic ultrasound in the treatment-planning process for esophageal carcinoma. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys. 2005;61:1123–8.

Buck AK, Halter G, Schirrmeister H, Kotzerke J, Wurziger I, Glatting G, et al. Imaging proliferation in lung tumors with PET: 18F-FLT versus 18F-FDG. J Nucl Med. 2003;44:1426–31.

Ma GW, Rong TH, Long H, Fu JH, Lin P, Huang ZF, et al. Shrinkage of resected specimens of esophageal carcinoma. Chin J Cancer. 2004;23:193–5.

Acknowledgements

This work was supported in part by Natural Science Foundation of China for the Youth, No.81101699, Natural Science Foundation of Shandong Province for the Youth, No.ZR2011HL059, Natural Science Foundation of China for the Youth, No.81301298. The authors would like to thank the reviewers for their insightful suggestions, which helped improve the manuscript.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Additional information

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Authors’ contributions

Dr. GFZ, JL and YY contribute to conception and design, draft the manuscript. Dr. DLH, CS Ma and JWZ contribute to acquire, analyze and interpret data. Dr. JZ, TS and THL contribute to acquire data and enhance its intellectual content. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Guifang Zhang and Dali Han contributed equally to this work.

Rights and permissions

This article is published under an open access license. Please check the 'Copyright Information' section either on this page or in the PDF for details of this license and what re-use is permitted. If your intended use exceeds what is permitted by the license or if you are unable to locate the licence and re-use information, please contact the Rights and Permissions team.

About this article

Cite this article

Zhang, G., Han, D., Ma, C. et al. Gradient-based delineation of the primary GTV on FLT PET in squamous cell cancer of the thoracic esophagus and impact on radiotherapy planning. Radiat Oncol 10, 11 (2015). https://doi.org/10.1186/s13014-014-0304-5

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/s13014-014-0304-5