Abstract

Background

Numerous implementation strategies to improve utilization of statins in patients with hypercholesterolemia have been utilized, with varying degrees of success. The aim of this systematic review is to determine the state of evidence of implementation strategies on the uptake of statins.

Methods and results

This systematic review identified and categorized implementation strategies, according to the Expert Recommendations for Implementing Change (ERIC) compilation, used in studies to improve statin use. We searched Ovid MEDLINE, Embase, Scopus, Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews, Cochrane Central Register of Controlled Trials, and Clinicaltrials.gov from inception to October 2018. All included studies were reported in English and had at least one strategy to promote statin uptake that could be categorized using the ERIC compilation. Data extraction was completed independently, in duplicate, and disagreements were resolved by consensus. We extracted LDL-C (concentration and target achievement), statin prescribing, and statin adherence (percentage and target achievement). A total of 258 strategies were used across 86 trials. The median number of strategies used was 3 (SD 2.2, range 1–13). Implementation strategy descriptions often did not include key defining characteristics: temporality was reported in 59%, dose in 52%, affected outcome in 9%, and justification in 6%. Thirty-one trials reported at least 1 of the 3 outcomes of interest: significantly reduced LDL-C (standardized mean difference [SMD] − 0.17, 95% CI − 0.27 to − 0.07, p = 0.0006; odds ratio [OR] 1.33, 95% CI 1.13 to 1.58, p = 0.0008), increased rates of statin prescribing (OR 2.21, 95% CI 1.60 to 3.06, p < 0.0001), and improved statin adherence (SMD 0.13, 95% CI 0.06 to 0.19; p = 0.0002; OR 1.30, 95% CI 1.04 to 1.63, p = 0.023). The number of implementation strategies used per study positively influenced the efficacy outcomes.

Conclusion

Although studies demonstrated improved statin prescribing, statin adherence, and reduced LDL-C, no single strategy or group of strategies consistently improved outcomes.

Trial registration

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Statin medications reduce low-density lipoprotein cholesterol (LDL-C) blood concentrations and cardiovascular events in patients with hypercholesterolemia, and guidelines recommend statin therapy to lower LDL-C in patients who are at risk for developing or have known atherosclerotic cardiovascular disease [1]. Despite evidence for the benefits of statins, the medications are widely underutilized [2,3,4,5,6]. Previous studies highlight both patient- and prescriber-barriers to statin use including side effects, competing medical conditions, busy clinics, and patient reluctance affecting adherence to prescribed medications [7,8,9]. Lack of adherence is associated with increased mortality in a dose dependent relationship [10].

Implementation strategies can be used to promote the uptake of interventions, such as statin therapy, and are defined as “methods or techniques used to enhance the adoption, implementation, and sustainability of a clinical program or practice” [11]. Numerous implementation strategies have been attempted to improve utilization of statins, all with varying degrees of success. These studies have targeted a variety of actors (e.g., patients, clinicians, or systems) and employed a variety of implementation strategies (e.g., education, reminders, or financial incentives). A computer-based clinical decision support system to aid in prescribing of evidence-based treatment for hyperlipidemia, which targeted clinicians, was found to significantly reduce blood LDL-C concentrations [12]. However, when providing financial incentives to providers, patients, or both, a study found that only the combination incentive was successful in reducing LDL-C levels to target [13]. The absolute and comparative effectiveness of these strategies, however, is unclear. Knowing which strategies are most effective can facilitate the uptake of statins and lead to reduce mortality.

To address this issue, we aimed to address the following key questions:

-

1.

What implementation strategies have been used to promote the uptake of statins?

-

2.

How completely are the implementation strategies utilized reported in studies designed to promote statin uptake?

-

3.

Which implementation strategy, or combination of strategies, is (are) the most effective at promoting the uptake of statins?

We conducted a systematic review of studies aimed at improving statin use and categorized implementation strategies by the Expert Recommendations for Implementing Change (ERIC) compilation [14]. Our primary objective was to better understand the impact of specific implementation strategies on the utilization of statins in patients with hypercholesterolemia. Our secondary objective was to evaluate statin adherence, statin prescribing, and lowering of LDL-C after intervention.

Methods

This registered (PROSPERO CRD42018114952) systematic review adhered to the reporting guidelines of the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-analyses (PRISMA) statement [15].

Search strategy

A medical librarian (L.H.Y.) searched the literature for records including the concepts of hypercholesterolemia, hyperlipidemia, and statins. The search strategies used a combination of keywords and controlled vocabulary and searched the following databases from inception to October 2018: MEDLINE, Embase, Scopus, Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews, Cochrane Central Register of Controlled Trials, and Clinicaltrials.gov. References were imported into Endnote™ and duplicates were identified and removed. An example of the search string can be found in Table 1 and the fully reproducible search strategies for each database can be found in Additional file 1: Appendix 1.

Study selection

We included studies reported in English, regardless of the country where the study was conducted, that had at least one strategy promoting statin uptake that could be categorized using the ERIC compilation [14, 16]. Seven manuscripts were excluded for this reason. The ERIC compilation was created so that researchers have a standardized way to name, define, and categorize implementation strategies. The ERIC compilation was selected for use in this review because the implementations strategies in the included articles most closely matched the ERIC taxonomy compared to other available choices [17]. For key questions 1 and 2, we did not limit inclusion based on study design or outcome. For key question 3, we limited inclusion to randomized controlled trials (RCTs). Studies were excluded for key questions if full text was not available.

Search results were uploaded into systematic review software (DistillerSR, Ottawa, Canada). In the first round of screening, abstracts and titles were evaluated for inclusion. Following abstract screening, eligibility was assessed through full-text screening. Prior to both abstract and full text screening, reviewers underwent training to ensure a basic understanding of the background of the field and purpose of the review as well as comprehension of the inclusion and exclusion criteria. The initial 20 abstracts were reviewed independently and then discussed as a group. Eligibility at both levels (abstract and full-text) was assessed independently and in duplicate (L.K.J., S.T., L.R.F., and C.G.). Disagreements at the level of abstract and full text screening were resolved by consensus. If consensus could not be achieved between the two reviewers, a third reviewer arbitrated (M.R.G., T.W., or T.S.).

Data collection

The following characteristics were extracted from included studies: first author, year of publication, location, age of patient population (adult vs. child), study design, implementation strategies, inclusion and exclusion criteria, and any of the following outcomes: statin prescribing or use, statin adherence, or LDL-C measurements.

Key question 1: what implementation strategies have been used to promote the uptake of statins?

We first summarized and described the populations, interventions, comparisons, and outcomes presented for all studies that reported at least one implementation strategy that could be mapped to the ERIC compilation. The ERIC compilation of nine implementation strategies categories (73 total strategies) was applied to each of the interventions to (1) count the total number of strategies and (2) describe how complete each implemented strategy was defined. One study team member, who was an author on the original ERIC compilation, ensured validity of the categories selected (T.W.) [14].

Key question 2: how completely are the implementation strategies utilized reported in studies designed to promote statin uptake?

Based on guidance from proctor and colleagues, we assessed the degree to which each strategy was completely reported including actor, action, action target, temporality, dose, implementation outcome affected, and justification (Table 2) [11].

Key question 3: which implementation strategy, or combination of strategies, is (are) the most effective at promoting the uptake of statins?

When present, we extracted data related to statin prescribing, statin adherence, and LDL-C reported from included RCTs. All outcomes were collected at intervention completion. Statin prescribing or use included all orders for statin medications. Statin adherence included only objective measures of adherence by either medication possession ratio (MPR) or proportion of days covered (PDC) [18]. MPR or PDC were captured as a percentage or attainment of greater than 80% adherence. LDL-C levels were recorded as LDL-C measured or achievement of an LDL-C target.

Risk of bias assessment

The Cochrane Collaboration’s risk of bias tool version 2 to evaluate methodological quality of studies included in the meta-analysis for key question 3 [19]. The risk of bias in included studies was assessed in duplicate by two reviewers (L.K.J. and L.R.F.) working independently. Any disagreements were resolved by consensus; if consensus was unable to be achieved, a third reviewer arbitrated (M.R.G.).

Statistical analysis

Standardized mean differences (SMDs) with corresponding 95% CIs were estimated for continuous outcomes, and odds ratios (ORs) and 95% confidence intervals (CIs) were calculated for binary outcomes from included studies. Publication bias was evaluated by Egger’s test [20]. Variability between included studies was assessed by heterogeneity tests using I2 statistic [21]. If overall results showed significant heterogeneity, potential sources of heterogeneity were explored by subgroup analysis. All analyses were conducted using RStudio (Version 1.0.136) using the “Meta” and “Metafor” package.

Results

Description of study selection

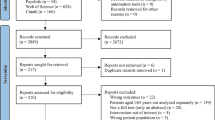

We initially identified 65,118 studies. After removing duplicates, we identified 38,585 unique citations (Fig. 1). Through abstract and title screening, 208 reports were identified for full-text review. During full-text review, 86 were selected for inclusion [12, 13, 22,23,24,25,26,27,28,29,30,31,32,33,34,35,36,37,38,39,40,41,42,43,44,45,46,47,48,49,50,51,52,53,54,55,56,57,58,59,60,61,62,63,64,65,66,67,68,69,70,71,72,73,74,75,76,77,78,79,80,81,82,83,84,85,86,87,88,89,90,91,92,93,94,95,96,97,98,99,100,101,102,103,104,105]. A complete list of excluded full-text studies with rationale for exclusion is available in Additional file 1: Appendix 2.

Description of studies

Table 3 describes the included studies (more details are included in Additional file 1: Appendix 3). Almost all the implementation strategies targeted adults (two studies included pediatric patients), half were implemented in the USA, and almost all were conducted in individuals with hypercholesterolemia (two studies were conducted in individuals with familial hypercholesterolemia).

Implementation strategies

All implementation strategies except “provide interactive assistance” were used (Table 4). A total of 258 uses of strategies were identified across 86 studies. On average, each study utilized three strategies (SD 2.2, range 1–13). The most utilized strategies were “train and educate the stakeholders” (studies utilized strategies in this grouping 79 times), “support clinicians” (68), and “engage consumers” (47). The most utilized individual strategies were “intervene with patients and consumers to enhance uptake and adherence” (41), and “distribute educational materials” (41) (Additional file 1: Appendix 4). Implementation strategies often did not include key defining characteristics: temporality was reported 59% of the time, dose 52%, affected outcome 9%, and justification 6% (Table 2 provides a summary and Additional file 1: Appendix 5 provides a more detailed version).

Meta-analysis

Due to the large heterogeneity between studies, effectiveness outcomes (statin prescribing, statin adherence, and LDL-C) were only extracted from RCTs. Thirty-one trials reported at least one of the three outcomes of interest. The implementation strategies examined demonstrated: significantly reduced LDL-C (LDL-C reduction: SMD − 0.17, 95% CI − 0.27 to − 0.07, p = 0.0006; met LDL-C target: OR 1.33, 95% CI 1.13 to 1.58, p = 0.0008) (Fig. 2), increased rates of statin prescribing (OR 2.21, 95% CI 1.60 to 3.06, p < 0.0001) (Fig. 3), and improved statin adherence (PDC/MPR: SMD 0.13, 95% CI 0.06 to 0.19; p = 0.0002; ≥ 80% PDC/MPR: OR 1.30, 95% CI 1.04 to 1.63, p = 0.023) (Fig. 4). There was inconsistency across trials based on the outcome measured; statin prescribing (I2 = 73%), statin adherence (I2 = 0%), and LDL-C (I2 = 79% (LDL-C reduction) and 76% (met LDL-C targets)). Publication bias using the Egger’s test indicated no publication bias for statin prescribing (p = 0.63), statin adherence (p = 0.83 for SMD, p = 0.22 for OR), and potential publication bias for LDL-C (p = 0.08 for SMD, p = 0.01 for OR).

Although subgroup analyses were conducted for statin prescribing and LDL-C, there were not enough studies to conduct a subgroup analysis for statin adherence (Table 5). We identified a significant difference among studies published in 2013 or later for LDL-C measured as a binary outcome (OR 1.62, 95% CI1.19–2.19, p = 0.05). We also found a significant effect on LDL-C measured as a continuous variable when more than 2 implementation strategies were utilized (SMD − 0.38 95% CI − 0.67; − 0.09, p = 0.05). There was no significant effect in the between country analysis.

Most studies were found to be at a low risk of bias (Fig. 5 and Additional file 1: Appendix 6); therefore, we did not conduct subgroup analyses based on the risk of bias.

Discussion

Our findings

In this review of implementation strategies regarding uptake of statins in hypercholesterolemia, we found that 38 different strategies were utilized to lower LDL-C, improve statin prescribing, and promote adherence. However, strategy components were not well defined and there was not a single strategy or group of strategies that demonstrated superior impact compared to others. Consistent with management of other diseases and conditions and literature from implementation science [106], we found evidence to support the use of multiple concurrent strategies; the use of three or more implementation strategies was associated with a greater reduction in LDL-C. We also found that studies published after 2012 had, on average, greater reductions in LDL-C through the use of the reported implementation strategies. While it cannot be definitely attributed, this could result from a better understanding of which strategies work best or could reflect a switch toward the utilization of high dose statin therapy. There was no difference in outcomes based on country where the study was conducted.

An important limitation of the many strategies described was incomplete definitions, limiting generalizability to other settings. Often, we were able to discern the actor, action, and action target but were unable to determine temporality, dose, implementation outcome affected, or justification. Without clear reporting of these factors, we are unable to interpret when these strategies should be used (temporality), how often (dosage), how the success of a specific strategy is measured (implementation outcomes affected), or when to justify the choice of a particular strategy (justification) to influence clinical practice. While the interventions appeared to be effective at increasing the utilization of statins and reducing LDL-C overall, the variable nature of the interventions studied and outcomes examined, the effectiveness of any specific strategy or set of strategies was unclear.

In addition, one category of strategies, “provide interactive assistance,” was not utilized in any of the studies included in the analysis. Among the strategies that were used, many were used in combination, but specific combinations were not used frequently enough to permit reliable subgroup analysis.

Comparison with other studies

In the field of implementation science, there has recently been a desire to improve specification of implementation strategies utilized in practice and to develop standard language and definitions for reporting these implementation strategies [11, 14, 107]. This trend has led to the development of two implementation strategy taxonomies: the ERIC compilation [14], used in this study, and the Effective Practise and Organization of Care (EPOC) taxonomy [17]. Use of these taxonomies has allowed for consistent language in reporting implementation strategies and development of tailored compilations of strategies specific to certain disease states [108, 109]. Other systematic reviews of implementation strategies in other fields (i.e., intensive care setting and oral health) have found improved outcomes when multiple implementation strategies are used but have not been able to identify the groups of strategies most likely to produce the most favorable outcomes [110,111,112].

An investigation of enablers and barriers to treatment adherence in familial hypercholesterolemia found seven enablers for patients that could be used to develop new interventions and matched to implementation strategies we identified in our study [113]. These enablers were “other family members following treatment regime,” “commencement of treatment from a young age,” “parental responsibility to care for children,” “confidence in ability to successfully self-manage their condition,” “receiving formal diagnosis of familial hypercholesterolemia,” “practical resources and support for following lifestyle treatment,” and a “positive relationship with healthcare professionals” [113]. By linking the two most frequently used strategies identified in our systematic review “intervene with patients and consumers to enhance uptake and adherence” and “distribute educational materials,” with the enablers identified above, effective implementations strategies for statin utilization can be designed.

The sustainability of interventions to promote the uptake of guidelines when intervening at the clinician level has been limited in a variety of settings [114,115,116]. Specifically, in cardiovascular disease, a systematic review of interventions to improve uptake of heart failure medications saw an increase in guideline uptake but not improvement in clinical outcomes [117]. Similar findings have been found in hypertension [118]. However, the success of these interventions have been limited.

Limitations and strengths

Our review is the first to comprehensively map the strategies used to increase utilization of statins among persons with hypercholesterolemia to the ERIC compilation. We chose to use ERIC due to a perceived better fit over alternatives (i.e. EPOC); however, we identified 7 studies (out of 208 identified) which could not be mapped to ERIC, exclusion of which could lead to missing important strategies. Other strengths include utilization of a medical librarian to conduct the search, searching of multiple databases which covered parts of the gray literature, and utilizing trained reviewers. Finally, we limited our search to studies in English with full-texts available. Thus, we may have missed studies not published in English or published in the gray literature (e.g., only conference abstract available in published literature) and be at risk for language bias [119] or publication bias [120]. While the Egger’s test suggested possible publication bias, we think that the risk of this is low due to our comprehensive search strategy. Further, while language bias is a possibility [119], few studies were excluded based on language so any potential impact is likely to be small.

Suggestions for future research

Consistent strategies for reporting LDL-C would significantly improve the ability to assess efficacy of an intervention. Some studies used arbitrary cut-offs for LDL-C, some used absolute values, and others used thresholds published in cholesterol guidelines [121]. This led to difficulty in aggregating data across studies. Future studies should report absolute values of LDL-C to facilitate meta-analyses directed at change of LDL-C with intervention. Generating a core outcome set for trials in hypercholesterolemia would facilitate meta-analyses and ensure all relevant outcomes are consistently measured [122]. Ideally, these studies should be registered and included in a meta-analysis in a prospective manner [123].

Clarity in the terminology, definition, and description of implementation strategies by researchers would help translation and replication of efforts. Completely reporting implementation strategies facilitates interpretation of results as well as facilitating reproducibility and scalability [11]. The field of implementation science offers guidance on how to name and report these strategies [11]. Even though this study was unable to identify a single or gold standard approach to improving statin therapy for hypercholesterolemia disorders, it provides examples of many different approaches that have some impact on outcomes relevant to care. In this way, this study provides a roadmap for future implementation to better define implementation strategies and to rigorously define and test the outcomes associated with those strategies. More guidance will be needed on the impact of strategies in different healthcare settings, because different strategies may work better in different healthcare settings so these idiosyncrasies need to be understood.

Conclusion

Implementation strategies to improve the uptake of statins among patients with hypercholesterolemia exist but they are poorly reported and generalizability is limited. While these strategies lowered LDL-C and improved adherence, significant heterogeneity made assessment of the comparative effectiveness of strategies difficult. Future studies for increasing the utilization of statins among patients with hypercholesterolemia should more clearly define strategies used, prospectively test comparative effectiveness of different strategies, and use standardized efficacy endpoints.

Availability of data and materials

All data generated or analyzed during this study are included in this published article and its supplementary information files.

Abbreviations

- CIs:

-

Confidence intervals

- ERIC:

-

Expert Recommendations for Implementing Change

- LDL-C:

-

Low density lipoprotein cholesterol

- ORs:

-

Odds ratios

- PRISMA:

-

Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-analyses

- SMDs:

-

Standardized mean differences

- RCTs:

-

Randomized clinical trails

References

Grundy SM, Stone NJ, Bailey AL, et al. 2018 AHA/ACC/AACVPR/AAPA/ABC/ACPM/ADA/AGS/APhA/ASPC/NLA/PCNA Guideline on the management of blood cholesterol: a report of the American College of Cardiology/American Heart Association Task Force on Clinical Practice Guidelines. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2019;139(25):e1082–143.

Akhabue E, Rittner SS, Carroll JE, et al. Implications of American College of Cardiology/American Heart Association (ACC/AHA) cholesterol guidelines on statin underutilization for prevention of cardiovascular disease in diabetes mellitus among several US networks of community health centers. J Am Heart Assoc. 2017;6(7):e005627.

Bansilal S, Castellano JM, Garrido E, Wei HG, Freeman A, Spettell C, et al. Assessing the impact of medication adherence on long-term cardiovascular outcomes. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2016;68(8):789–801. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jacc.2016.06.005.

Martin-Ruiz E, Olry-de-Labry-Lima A, Ocaña-Riola R, Epstein D. Systematic review of the effect of adherence to statin treatment on critical cardiovascular events and mortality in primary prevention. J Cardiovasc Pharmacol Ther. 2018;23(3):200–15. https://doi.org/10.1177/1074248417745357.

De Vera MA, Bhole V, Burns LC, Lacaille D. Impact of statin adherence on cardiovascular disease and mortality outcomes: a systematic review. Br J Clin Pharmacol. 2014;78(4):684–98. https://doi.org/10.1111/bcp.12339.

Rodriguez F, Maron DJ, Knowles JW, Virani SS, Lin S, Heidenreich PA. Association of statin adherence with mortality in patients with atherosclerotic cardiovascular disease. JAMA Cardiol. 2019;4(3):206–13. https://doi.org/10.1001/jamacardio.2018.4936.

Jones LK, Sturm AC, Seaton TL, Gregor C, Gidding SS, Williams MS, et al. Barriers, facilitators, and solutions to familial hypercholesterolemia treatment. PLoS One. 2020;15(12):e0244193. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0244193.

Tanner RM, Safford MM, Monda KL, Taylor B, O’Beirne R, Morris M, et al. Primary care physician perspectives on barriers to statin treatment. Cardiovasc Drugs Ther. 2017;31(3):303–9. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10557-017-6738-x.

Ju A, Hanson CS, Banks E, Korda R, Craig JC, Usherwood T, et al. Patient beliefs and attitudes to taking statins: systematic review of qualitative studies. Br J Gen Pract. 2018;68(671):e408–19. https://doi.org/10.3399/bjgp18X696365.

Lansberg P, Lee A, Lee Z-V, Subramaniam K, Setia S. Nonadherence to statins: individualized intervention strategies outside the pill box. Vasc Health Risk Manag. 2018;14:91–102. https://doi.org/10.2147/VHRM.S158641.

Proctor EK, Powell BJ, McMillen JC. Implementation strategies: recommendations for specifying and reporting. Implement Sci. 2013;8(1):139. https://doi.org/10.1186/1748-5908-8-139.

Zamora A, Fernández De Bobadilla F, Carrion C, et al. Pilot study to validate a computer-based clinical decision support system for dyslipidemia treatment (HTE-DLP). Atherosclerosis. 2013;231(2):401–4. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.atherosclerosis.2013.09.029.

Asch DA, Troxel AB, Stewart WF, Sequist TD, Jones JB, Hirsch AMG, et al. Effect of financial incentives to physicians, patients, or both on lipid levels: a randomized clinical trial. JAMA. 2015;314(18):1926–35. https://doi.org/10.1001/jama.2015.14850.

Powell BJ, Waltz TJ, Chinman MJ, Damschroder LJ, Smith JL, Matthieu MM, et al. A refined compilation of implementation strategies: results from the Expert Recommendations for Implementing Change (ERIC) project. Implement Sci. 2015;10(1):21. https://doi.org/10.1186/s13012-015-0209-1.

Moher D, Liberati A, Tetzlaff J, Altman DG. Preferred reporting items for systematic reviews and meta-analyses: the PRISMA statement. PLoS Med. 2009;6(7):e1000097. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pmed.1000097.

Waltz TJ, Powell BJ, Matthieu MM, Damschroder LJ, Chinman MJ, Smith JL, et al. Use of concept mapping to characterize relationships among implementation strategies and assess their feasibility and importance: results from the Expert Recommendations for Implementing Change (ERIC) study. Implement Sci. 2015;10(1):109. https://doi.org/10.1186/s13012-015-0295-0.

Effective Practice and Organisation of Care (EPOC). 2015; epoc.cochrane.org/epoc-taxonomy Accessed 1 Feb 2021.

Nau DP. Proportion of days covered (PDC) as a preferred method of measuring medication adherence: Pharmacy Quality Alliance; 2012.

Sterne JAC, Savovic J, Page MJ, et al. RoB 2: a revised tool for assessing risk of bias in randomised trials. BMJ. 2019;366:l4898.

Sterne JA, Egger M. Funnel plots for detecting bias in meta-analysis: guidelines on choice of axis. J Clin Epidemiol. 2001;54(10):1046–55. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0895-4356(01)00377-8.

Higgins JP, Thompson SG, Deeks JJ, Altman DG. Measuring inconsistency in meta-analyses. BMJ. 2003;327(7414):557–60. https://doi.org/10.1136/bmj.327.7414.557.

Weng S, Kai J, Tranter J, Leonardi-Bee J, Qureshi N. Improving identification and management of familial hypercholesterolaemia in primary care: Pre- and post-intervention study. Atherosclerosis. 2018;274:54–60. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.atherosclerosis.2018.04.037.

Webster R, Li SC, Sullivan DR, Jayne K, Su SY, Neal B. Effects of internet-based tailored advice on the use of cholesterol-lowering interventions: a randomized controlled trial. J Med Internet Res. 2010;12(3):e42. https://doi.org/10.2196/jmir.1364.

Vrijens B, Belmans A, Matthys K, de Klerk E, Lesaffre E. Effect of intervention through a pharmaceutical care program on patient adherence with prescribed once-daily atorvastatin. Pharmacoepidemiol Drug Saf. 2006;15(2):115–21. https://doi.org/10.1002/pds.1198.

Viola RA, Abbott KC, Welch PG, McMillan RJ, Sheikh AM, Yuan CM. A multidisciplinary program for achieving lipid goals in chronic hemodialysis patients. BMC Nephrol. 2002;3:1–7.

Vinker S, Bitterman H, Comaneshter D, Cohen AD. Physicians’ behavior following changes in LDL cholesterol target goals. Isr J Health Policy Res. 2015;4(1):20.

Truppo C, Keller VA, Reusch MT, Pandya B, Bendich D. The effect of a comprehensive, mail-based motivational program for patients receiving lipid-lowering therapy. Manag Care Interface. 2003;16(3):35–40+62.

Straka RJ, Taheri R, Cooper SL, Smith JC. Achieving cholesterol target in a managed care organization (ACTION) trial. Pharmacotherapy. 2005;25(3):360–71. https://doi.org/10.1592/phco.25.3.360.61601.

Stockl KM, Tjioe D, Gong S, Stroup J, Harada ASM, Lew HC. Effect of an intervention to increase statin use in medicare members who qualified for a medication therapy management program. J Manag Care Pharm. 2008;14(6):532–40. https://doi.org/10.18553/jmcp.2008.14.6.532.

Stephenson SH, Larrinaga-Shum S, Hopkins PN. Benefits of the MEDPED treatment support program for patients with familial hypercholesterolemia. J Clin Lipidol. 2009;3(2):94–100. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jacl.2009.02.004.

Stacy JN, Schwartz SM, Ershoff D, Shreve MS. Incorporating tailored interactive patient solutions using interactive voice response technology to improve statin adherence: results of a randomized clinical trial in a managed care setting. Popul Health Manage. 2009;12(5):241–54. https://doi.org/10.1089/pop.2008.0046.

Shibley MCH, Pugh CB. Implementation of pharmaceutical care services for patients with hyperlipidemias by independent community pharmacy practitioners. Ann Pharmacother. 1997;31(6):713–9. https://doi.org/10.1177/106002809703100608.

Schwed A, Fallab CL, Burnier M, Waeber B, Kappenberger L, Burnand B, et al. Electronic monitoring of compliance to lipid-lowering therapy in clinical practice. J Clin Pharmacol. 1999;39(4):402–9. https://doi.org/10.1177/00912709922007976.

Schectman G, Wolff N, Byrd JC, Hiatt JG, Hartz A. Physician extenders for cost-effective management of hypercholesterolemia. J Gen Intern Med. 1996;11(5):277–86. https://doi.org/10.1007/BF02598268.

Riesen WF, Noll G, Dariolu R. Impact of enhanced compliance initiatives on the efficacy of rosuvastatin in reducing low density lipoprotein cholesterol levels in patients with primary hypercholesterolaemia. Swiss Med Wkly. 2008;138(29-30):420–6 DOI: 2008/29/smw-12120.

Rachmani R, Slavacheski I, Berla M, Frommer-Shapira R, Ravid M. Treatment of high-risk patients with diabetes: motivation and teaching intervention: a randomized, prospective 8-year follow-up study. J Am Soc Nephrol. 2005;16(3 SUPPL. 1):S22–6.

Nordmann A, Blattmann L, Gallino A, Khetari R, Martina B, Müller P, et al. Systematic, immediate in-hospital initiation of lipid-lowering drugs during acute coronary events improves lipid control. Eur J Internal Med. 2000;11(6):309–16. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0953-6205(00)00110-2.

Nguyen G, Cruickshank J, Mouillard A, Dumuis ML, Picard C, Cailleteau X, et al. Comparison of achievement of treatment targets as perceived by physicians and as calculated after implementation of clinical guidelines for the management of hypercholesterolemia in a randomized, clinical trial. Curr Ther Res Clin Exp. 2000;61(9):597–608. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0011-393X(00)88012-1.

Lindholm LH, Ekbom T, Dash C. Changes in cardiovascular risk factors by combined pharmacological and nonpharmacological strategies: the main results of the CELL study. J Intern Med. 1996;240(1):13–22. https://doi.org/10.1046/j.1365-2796.1996.492831000.x.

Lima EMO, Gualandro DM, Yu PC, Giuliano ICB, Marques AC, Calderaro D, et al. Cardiovascular prevention in HIV patients: results from a successful intervention program. Atherosclerosis. 2009;204(1):229–32. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.atherosclerosis.2008.08.017.

Lester WT, Grant RW, Barnett GO, Chueh HC. Randomized controlled trial of an informatics-based intervention to increase statin prescription for secondary prevention of coronary disease. J Gen Intern Med. 2006;21(1):22–9. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1525-1497.2005.00268.x.

Kooy MJ, Van Wijk BLG, Heerdink ER, De Boer A, Bouvy ML. Does the use of an electronic reminder device with or without counseling improve adherence to lipid-lowering treatment? The results of a randomized controlled trial. Front Pharmacol. 2013;4:69.

Kardas P. An education-behavioural intervention improves adherence to statins. Cent Eur J Med. 2013;8(5):580–5.

Jakobsson S, Huber D, Björklund F, Mooe T. Implementation of a new guideline in cardiovascular secondary preventive care: subanalysis of a randomized controlled trial. BMC Cardiovasc Disord. 2016;16(1):1–9.

Hilleman DE, Faulkner MA, Monaghan MS. Cost of a pharmacist-directed intervention to increase treatment of hypercholesterolemia. Pharmacotherapy. 2004;24(8):1077–83. https://doi.org/10.1592/phco.24.11.1077.36145.

Harrison TN, Green KR, Liu ILA, Vansomphone SS, Handler J, Scott RD, et al. Automated outreach for cardiovascular-related medication refill reminders. J Clin Hypertens. 2016;18(7):641–6. https://doi.org/10.1111/jch.12723.

Harats D, Leibovitz E, Maislos M, Wolfovitz E, Chajek-Shaul T, Leitersdorf E, et al. Cardiovascular risk assessment and treatment to target low density lipoprotein levels in hospitalized ischemic heart disease patients: results of the HOLEM study. Isr Med Assoc J. 2005;7(6):355–9.

Goldberg KC, Melnyk SD, Simel DL. Overcoming inertia: improvement in achieving target low-density lipoprotein cholesterol. Am J Manag Care. 2007;13(9):530–4.

Gitt AK, Jünger C, Jannowitz C, Karmann B, Senges J, Bestehorn K. Adherence of hospital-based cardiologists to lipid guidelines in patients at high risk for cardiovascular events (2L registry). Clin Res Cardiol. 2011;100(4):277–87. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00392-010-0240-9.

Geber J, Parra D, Beckey NP, Korman L. Optimizing drug therapy in patients with cardiovascular disease: the impact of pharmacist-managed pharmacotherapy clinics in a primary care setting. Pharmacotherapy. 2002;22(6 I):738–47.

Gavish D, Leibovitz E, Elly I, Shargorodsky M, Zimlichman R. Follow-up in a lipid clinic improves the management of risk factors in cardiovascular disease patients. Isr Med Assoc J. 2002;4(9):694–7.

Ford DR, Walker J, Game FL, Bartlett WA, Jones AF. Effect of computerized coronary heart disease risk assessment on the use of lipid-lowering therapy in general practice patients. Coron Health Care. 2001;5(1):4–8. https://doi.org/10.1054/chec.2000.0103.

Etxeberria A, Alcorta I, Pérez I, Emparanza JI, Ruiz de Velasco E, Iglesias MT, et al. Results from the CLUES study: a cluster randomized trial for the evaluation of cardiovascular guideline implementation in primary care in Spain. BMC Health Serv Res. 2018;18(1):93. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12913-018-2863-x.

Mols RE, Jensen JM, Sand NP, et al. Visualization of coronary artery calcification: influence on risk modification. Am J Med. 2015;128(9):1023.e1023–31.

Dresser GK, Nelson SAE, Mahon JL, Zou G, Vandervoort MK, Wong CJ, et al. Simplified therapeutic intervention to control hypertension and hypercholesterolemia: a cluster randomized controlled trial (STITCH2). J Hypertens. 2013;31(8):1702–13. https://doi.org/10.1097/HJH.0b013e3283619d6a.

de Velasco JA, Cosín J, de Oya M, de Teresa E. Intervention program to improve secondary prevention of Myocardial infarction. Results of the PRESENTE (Early Secondary Prevention) study. Rev Esp Cardiol. 2004;57(2):146–54.

De Lusignan S, Belsey J, Hague N, Dhoul N, Van Vlymen J. Audit-based education to reduce suboptimal management of cholesterol in primary care: a before and after study. J Public Health. 2006;28(4):361–9. https://doi.org/10.1093/pubmed/fdl052.

Chung JST, Lee KKC, Tomlinson B, Lee VWY. Clinical and economic impact of clinical pharmacy service on hyperlipidemic management in Hong Kong. J Cardiovasc Pharmacol Ther. 2011;16(1):43–52. https://doi.org/10.1177/1074248410380207.

Casebeer L, Huber C, Bennett N, et al. Improving the physician-patient cardiovascular risk dialogue to improve statin adherence. BMC Fam Pract. 2009;10:48. https://doi.org/10.1186/1471-2296-10-48.

Brath H, Morak J, Kästenbauer T, Modre-Osprian R, Strohner-Kästenbauer H, Schwarz M, et al. Mobile health (mHealth) based medication adherence measurement—a pilot trial using electronic blisters in diabetes patients. Br J Clin Pharmacol. 2013;76(S1):47–55. https://doi.org/10.1111/bcp.12184.

Bosworth HB, Brown JN, Danus S, Sanders LL, McCant F, Zullig LL, et al. Evaluation of a packaging approach to improve cholesterol medication adherence. Am J Manag Care. 2017;23(9):e280–6.

Bhattacharyya O, Harris S, Zwarenstein M, Barnsley J. Controlled trial of an intervention to improve cholesterol management in diabetes patients in remote Aboriginal communities. Int J Circumpolar Health. 2010;69(4):333–43. https://doi.org/10.3402/ijch.v69i4.17629.

Bassa A, Del Val M, Cobos A, et al. Impact of a clinical decision support system on the management of patients with hypercholesterolemia in the primary healthcare setting. Dis Manag Health Outcomes. 2005;13(1):65–72. https://doi.org/10.2165/00115677-200513010-00007.

Andrews SB, Marcy TR, Osborn B, Planas LG. The impact of an appointment-based medication synchronization programme on chronic medication adherence in an adult community pharmacy population. J Clin Pharm Ther. 2017;42(4):461–6. https://doi.org/10.1111/jcpt.12533.

Bogden PE, Koontz LM, Williamson P, Abbott RD. The physician and pharmacist team: An effective approach to cholesterol reduction. J Gen Intern Med. 1997;12(3):158–64.

Rehring TF, Stolcpart RS, Sandhoff BG, Merenich JA, Hollis HW Jr. Effect of a clinical pharmacy service on lipid control in patients with peripheral arterial disease. J Vasc Surg. 2006;43(6):1205–10. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jvs.2006.02.019.

Hatfield J, Gulati S, Abdul Rahman MNA, Coughlin PA, Chetter IC. Nurse-led risk assessment/management clinics reduce predicted cardiac morbidity and mortality in claudicants. J Vasc Nurs. 2008;26(4):118–22. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jvn.2008.09.004.

Aziz EF, Javed F, Pulimi S, Pratap B, de Benedetti Zunino ME, Tormey D, et al. Implementing a pathway for the management of acute coronary syndrome leads to improved compliance with guidelines and a decrease in angina symptoms. J Healthc Qual. 2012;34(4):5–14. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1945-1474.2011.00145.x.

Lappé JM, Muhlestein JB, Lappé DL, et al. Improvements in 1-year cardiovascular clinical outcomes associated with a hospital-based discharge medication program. Ann Intern Med. 2004;141(6):446–453+I-443.

Hilleman D, Monaghan M, Ashby C, Mashni J, Wooley K, Amato C. Simple physician-prompting intervention drastically improves outcomes in CHD. Formulary. 2002;37:209–10.

Faulkner MA, Wadibia EC, Lucas BD, Hilleman DE. Impact of pharmacy counseling on compliance and effectiveness of combination lipid-lowering therapy in patients undergoing coronary artery revascularization: a randomized, controlled trial. Pharmacotherapy. 2000;20(4):410–6. https://doi.org/10.1592/phco.20.5.410.35048.

Goswami NJ, DeKoven M, Kuznik A, et al. Impact of an integrated intervention program on atorvastatin adherence: a randomized controlled trial. Int J Gen Med. 2013;6:647–55. https://doi.org/10.2147/IJGM.S47518.

Clark B, DuChane J, Hou J, Rubinstein E, McMurray J, Duncan I. Evaluation of increased adherence and cost savings of an employer value-based benefits program targeting generic antihyperlipidemic and antidiabetic medications. J Manag Care Pharm. 2014;20(2):141–50. https://doi.org/10.18553/jmcp.2014.20.2.141.

Farley JF, Wansink D, Lindquist JH, Parker JC, Maciejewski ML. Medication adherence changes following value-based insurance design. Am J Manag Care. 2012;18(5):265–74.

Chen C, Chen K, Hsu CY, Chiu WT, Li YC. A guideline-based decision support for pharmacological treatment can improve the quality of hyperlipidemia management. Comput Methods Prog Biomed. 2010;97(3):280–5. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cmpb.2009.12.004.

Choudhry NK, Isaac T, Lauffenburger JC, et al. Effect of a remotely delivered tailored multicomponent approach to enhance medication taking for patients with hyperlipidemia, hypertension, and diabetes the STIC2IT cluster randomized clinical trial. JAMA Intern Med. 2018;178(9):1190–8.

Khanal S, Obeidat O, Hudson MP, et al. Active lipid management in coronary artery disease (ALMICAD) study. Am J Med. 2007;120(8):734.e711–7.

Lee JK, Grace KA, Taylor AJ. Effect of a pharmacy care program on medication adherence and persistence, blood pressure, and low-density lipoprotein cholesterol: a randomized controlled trial. J Am Med Assoc. 2006;296(21):2563–71. https://doi.org/10.1001/jama.296.21.joc60162.

Damush TM, Myers L, Anderson JA, Yu Z, Ofner S, Nicholas G, et al. The effect of a locally adapted, secondary stroke risk factor self-management program on medication adherence among veterans with stroke/TIA.[Erratum appears in Transl Behav Med. 2016 Sep;6(3):469; PMID: 27528534]. Transl Behav Med. 2016;6(3):457–68. https://doi.org/10.1007/s13142-015-0348-6.

Mehrpooya M, Larki-Harchegani A, Ahmadimoghaddam D, et al. Evaluation of the effect of education provided by pharmacists on hyperlipidemic patient’s adherence to medications and blood level of lipids. J Appl Pharm Sci. 2018;8(1):029–33.

Párraga-Martínez I, Escobar-Rabadán F, Rabanales-Sotos J, Lago-Deibe F, Téllez-Lapeira JM, Villena-Ferrer A, et al. Efficacy of a combined strategy to improve low-density lipoprotein cholesterol control among patients with hypercholesterolemia: a randomized clinical trial. Rev Esp Cardiol. 2018;71(1):33–41. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.recesp.2017.03.019.

Patel A, Cass A, Peiris D, Usherwood T, Brown A, Jan S, et al. A pragmatic randomized trial of a polypill-based strategy to improve use of indicated preventive treatments in people at high cardiovascular disease risk. Eur J Prev Cardiol. 2015;22(7):920–30. https://doi.org/10.1177/2047487314530382.

McAlister FA, Majumdar SR, Padwal RS, et al. Case management for blood pressure and lipid level control after minor stroke: PREVENTION randomized controlled trial. CMAJ. 2014;186(8):577–84. https://doi.org/10.1503/cmaj.140053.

Shoulders BR, Franks AS, Barlow PB, Williams JD, Farland MZ. Impact of pharmacists’ interventions and simvastatin dose restrictions. Ann Pharmacother. 2014;48(1):54–61. https://doi.org/10.1177/1060028013511323.

Derose SF, Green K, Marrett E, Tunceli K, Cheetham TC, Chiu VY, et al. Automated outreach to increase primary adherence to cholesterol-lowering medications. JAMA Intern Med. 2013;173(1):38–43. https://doi.org/10.1001/2013.jamainternmed.717.

Nieuwkerk PT, Nierman MC, Vissers MN, Locadia M, Greggers-Peusch P, Knape LPM, et al. Intervention to improve adherence to lipid-lowering medication and lipid-levels in patients with an increased cardiovascular risk. Am J Cardiol. 2012;110(5):666–72. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.amjcard.2012.04.045.

Schmittdiel JA, Karter AJ, Dyer W, Parker M, Uratsu C, Chan J, et al. The comparative effectiveness of mail order pharmacy use vs. local pharmacy use on LDL-C control in new statin users. J Gen Intern Med. 2011;26(12):1396–402. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11606-011-1805-7.

Coodley GO, Jorgensen M, Kirschenbaum J, Sparks C, Zeigler L, Albertson BD. Lowering LDL Cholesterol in adults: a prospective, community-based practice initiative. Am J Med. 2008;121(7):604–10. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.amjmed.2008.02.031.

Willich SN, Englert H, Sonntag F, Völler H, Meyer-Sabellek W, Wegscheider K, et al. Impact of a compliance program on cholesterol control: Results of the randomized ORBITAL study in 8108 patients treated with rosuvastatin. Eur J Prev Cardiol. 2009;16(2):180–7. https://doi.org/10.1097/HJR.0b013e3283262ac3.

Hung CS, Lin JW, Hwang JJ, Tsai RY, Li AT. Using paper chart based clinical reminders to improve guideline adherence to lipid management. J Eval Clin Pract. 2008;14(5):861–6. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1365-2753.2008.01066.x.

Brady AJB, Pittard JB, Grace JF, Robinson PJ. Clinical assessment alone will not benefit patients with coronary heart disease: failure to achieve cholesterol targets in 12,045 patients - The Healthwise II study. Int J Clin Pract. 2005;59(3):342–5. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1742-1241.2005.00365.x.

Robinson JG, Conroy C, Wickemeyer WJ. A novel telephone-based system for management of secondary prevention to a low-density lipoprotein cholesterol < or = 100 mg/dl. Am J Cardiol. 2000;85(3):305–8. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0002-9149(99)00737-7.

Birtcher KK, Bowden C, Ballantyne CM, Huyen M. Strategies for implementing lipid-lowering therapy: pharmacy-based approach. Am J Cardiol. 2000;85(3 SUPPL. 1):30–5.

Shaffer J, Wexler LF. Reducing low-density lipoprotein cholesterol levels in an ambulatory care system: results of a multidisciplinary collaborative practice lipid clinic compared with traditional physician-based care. Arch Intern Med. 1995;155(21):2330–5. https://doi.org/10.1001/archinte.1995.00430210080012.

Choe HM, Stevenson JG, Streetman DS, Heisler M, Sandiford CJ, Piette JD. Impact of patient financial incentives on participation and outcomes in a statin pill-splitting program. Am J Manag Care. 2007;13(6 Part 1):298–304.

McLeod AL, Brooks L, Taylor V, Wylie A, Currie PF, Dewhurst NG. Non-attendance at secondary prevention clinics: the effect on lipid management. Scott Med J. 2005;50(2):54–6. https://doi.org/10.1177/003693300505000204.

Rabinowitz I, Tamir A. The SaM (Screening and Monitoring) approach to cardiovascular risk-reduction in primary care—cyclic monitoring and individual treatment of patients at cardiovascular risk using the electronic medical record. Eur J Cardiovasc Prev Rehabil. 2005;12(1):56–62.

Ryan MJ, Gibson J, Simmons P, Stanek E. Effectiveness of aggressive management of dyslipidemia in a collaborative-care practice model. Am J Cardiol. 2003;91(12):1427–31. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0002-9149(03)00393-X.

Sebregts EH, Falger PR, Bär FW, Kester AD, Appels A. Cholesterol changes in coronary patients after a short behavior modification program. Int J Behav Med. 2003;10(4):315–30. https://doi.org/10.1207/S15327558IJBM1004_3.

Lowrie R, Lloyd SM, McConnachie A, Morrison J. A cluster randomised controlled trial of a pharmacist-led collaborative intervention to improve statin prescribing and attainment of cholesterol targets in primary care. PLoS One. 2014;9(11):e113370. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0113370.

McAlister FA, Fradette M, Majumdar SR, et al. The enhancing secondary prevention in coronary artery disease trial. CMAJ. 2009;181(12):897–904. https://doi.org/10.1503/cmaj.090917.

Persell SD, Shah S, Brown T, et al. Individualized risk communication and lay outreach for the primary prevention of cardiovascular disease in community health centers: a randomized controlled trial. Circulation. 2015;130:A14008.

Villeneuve J, Genest J, Blais L, Vanier MC, Lamarre D, Fredette M, et al. A cluster randomized controlled trial to evaluate an ambulatory primary care management program for patients with dyslipidemia: the TEAM study. CMAJ. 2010;182(5):447–55. https://doi.org/10.1503/cmaj.090533.

Osborn D, Burton A, Hunter R, Marston L, Atkins L, Barnes T, et al. Clinical and cost-effectiveness of an intervention for reducing cholesterol and cardiovascular risk for people with severe mental illness in English primary care: a cluster randomised controlled trial. Lancet Psychiatry. 2018;5(2):145–54. https://doi.org/10.1016/S2215-0366(18)30007-5.

Paulós CP, Akesson Nygren CE, Celedón C, Cárcamo CA. Impact of a pharmaceutical care program in a community pharmacy on patients with dyslipidemia. Ann Pharmacother. 2005;39(5):939–43. https://doi.org/10.1345/aph.1E347.

Briss PA, Brownson RC, Fielding JE, Zaza S. Developing and using the guide to community preventive services: lessons learned about evidence-based public health. Annu Rev Public Health. 2004;25(1):281–302. https://doi.org/10.1146/annurev.publhealth.25.050503.153933.

Powell BJ, Fernandez ME, Williams NJ, et al. Enhancing the Impact of Implementation Strategies in Healthcare: A Research Agenda. Front Public Health. 2019;7:3. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpubh.2019.00003.

Powell BJ, McMillen JC, Proctor EK, et al. A compilation of strategies for implementing clinical innovations in health and mental health. Med Care Res Rev. 2012;69(2):123–57. https://doi.org/10.1177/1077558711430690.

Graham AK, Lattie EG, Powell BJ, Lyon AR, Smith JD, Schueller SM, et al. Implementation strategies for digital mental health interventions in health care settings. Am Psychol. 2020;75(8):1080–92. https://doi.org/10.1037/amp0000686.

Trogrlić Z, van der Jagt M, Bakker J, et al. A systematic review of implementation strategies for assessment, prevention, and management of ICU delirium and their effect on clinical outcomes. Crit Care. 2015;19(1):157.

Yi Mohammadi JJ, Franks K, Hines S. Effectiveness of professional oral health care intervention on the oral health of residents with dementia in residential aged care facilities: a systematic review protocol. JBI Database System Rev Implement Rep. 2015;13(10):110–22. https://doi.org/10.11124/jbisrir-2015-2330.

Mills KT, Obst KM, Shen W, Molina S, Zhang HJ, He H, et al. Comparative effectiveness of implementation strategies for blood pressure control in hypertensive patients: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Ann Intern Med. 2018;168(2):110–20. https://doi.org/10.7326/M17-1805.

Kinnear FJ, Wainwright E, Perry R, Lithander FE, Bayly G, Huntley A, et al. Enablers and barriers to treatment adherence in heterozygous familial hypercholesterolaemia: a qualitative evidence synthesis. BMJ Open. 2019;9(7):e030290. https://doi.org/10.1136/bmjopen-2019-030290.

Ament SM, de Groot JJ, Maessen JM, Dirksen CD, van der Weijden T, Kleijnen J. Sustainability of professionals' adherence to clinical practice guidelines in medical care: a systematic review. BMJ Open. 2015;5(12):e008073. https://doi.org/10.1136/bmjopen-2015-008073.

Jordan P, Mpasa F, Ten Ham-Baloyi W, Bowers C. Implementation strategies for guidelines at ICUs: a systematic review. Int J Health Care Qual Assur. 2017;30(4):358–72. https://doi.org/10.1108/IJHCQA-08-2016-0119.

Unverzagt S, Oemler M, Braun K, Klement A. Strategies for guideline implementation in primary care focusing on patients with cardiovascular disease: a systematic review. Fam Pract. 2014;31(3):247–66. https://doi.org/10.1093/fampra/cmt080.

Shanbhag D, Graham ID, Harlos K, Haynes RB, Gabizon I, Connolly SJ, et al. Effectiveness of implementation interventions in improving physician adherence to guideline recommendations in heart failure: a systematic review. BMJ Open. 2018;8(3):e017765. https://doi.org/10.1136/bmjopen-2017-017765.

Milchak JL, Carter BL, James PA, Ardery G. Measuring adherence to practice guidelines for the management of hypertension: an evaluation of the literature. Hypertension. 2004;44(5):602–8.

Morrison A, Polisena J, Husereau D, Moulton K, Clark M, Fiander M, et al. The effect of English-language restriction on systematic review-based meta-analyses: a systematic review of empirical studies. Int J Technol Assess Health Care. 2012;28(2):138–44. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0266462312000086.

Schmucker CM, Blumle A, Schell LK, et al. Systematic review finds that study data not published in full text articles have unclear impact on meta-analyses results in medical research. PLoS One. 2017;12(4):e0176210. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0176210.

Bays HE, Jones PH, Brown WV, Jacobson TA, National LA. National lipid association annual summary of clinical lipidology 2015. J Clin Lipidol. 2014;8(6 Suppl):S1–36. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jacl.2014.10.002.

Williamson PR, Altman DG, Bagley H, et al. The COMET Handbook: version 1.0. Trials. 2017;18(3):280.

Seidler AL, Hunter KE, Cheyne S, Ghersi D, Berlin JA, Askie L. A guide to prospective meta-analysis. BMJ. 2019;367:l5342.

Acknowledgements

Not applicable.

Funding

Research reported in this publication was supported by the National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute of the National Institutes of Health under Award Number K12HL137942.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

LKJ designed the systematic review, reviewed abstracts and full-text, extracted and analyzed data, and prepared the manuscript file. ST and CG reviewed abstracts and full-text for inclusion and extracted data and reviewed manuscript file. LHY completed search and reviewed final manuscript file. YH performed statistical analyses and risk of bias and reviewed final manuscript. ACS, AKR, AG, RCB, and SSG reviewed data and reviewed final manuscript. TLS and TJW reviewed implementation strategies categorization and final manuscript. MSW and MRG designed systematic review, reviewed data, and prepared and reviewed final manuscript. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate

Not applicable. Registered in PROSPERO.

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary Information

Additional file 1: Appendix 1

. Statin uptake search strategy. Appendix 2. Excluded full text articles and rationale. Appendix 3. Detailed study demographics. Appendix 4. Count of implementation strategy organized by category and strategy. Appendix 5. Detailed Proctor’s framework description of each strategy. Appendix 6. Risk of bias

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/. The Creative Commons Public Domain Dedication waiver (http://creativecommons.org/publicdomain/zero/1.0/) applies to the data made available in this article, unless otherwise stated in a credit line to the data.

About this article

Cite this article

Jones, L.K., Tilberry, S., Gregor, C. et al. Implementation strategies to improve statin utilization in individuals with hypercholesterolemia: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Implementation Sci 16, 40 (2021). https://doi.org/10.1186/s13012-021-01108-0

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/s13012-021-01108-0