Abstract

Background

Despite the availability of evidence-based guidelines for the management of mild traumatic brain injury in the emergency department (ED), variations in practice exist. Interventions designed to implement recommended behaviours can reduce this variation. Using theory to inform intervention development is advocated; however, there is no consensus on how to select or apply theory. Integrative theoretical frameworks, based on syntheses of theories and theoretical constructs relevant to implementation, have the potential to assist in the intervention development process. This paper describes the process of applying two theoretical frameworks to investigate the factors influencing recommended behaviours and the choice of behaviour change techniques and modes of delivery for an implementation intervention.

Methods

A stepped approach was followed: (i) identification of locally applicable and actionable evidence-based recommendations as targets for change, (ii) selection and use of two theoretical frameworks for identifying barriers to and enablers of change (Theoretical Domains Framework and Model of Diffusion of Innovations in Service Organisations) and (iii) identification and operationalisation of intervention components (behaviour change techniques and modes of delivery) to address the barriers and enhance the enablers, informed by theory, evidence and feasibility/acceptability considerations. We illustrate this process in relation to one recommendation, prospective assessment of post-traumatic amnesia (PTA) by ED staff using a validated tool.

Results

Four recommendations for managing mild traumatic brain injury were targeted with the intervention. The intervention targeting the PTA recommendation consisted of 14 behaviour change techniques and addressed 6 theoretical domains and 5 organisational domains. The mode of delivery was informed by six Cochrane reviews. It was delivered via five intervention components : (i) local stakeholder meetings, (ii) identification of local opinion leader teams, (iii) a train-the-trainer workshop for appointed local opinion leaders, (iv) local training workshops for delivery by trained local opinion leaders and (v) provision of tools and materials to prompt recommended behaviours.

Conclusions

Two theoretical frameworks were used in a complementary manner to inform intervention development in managing mild traumatic brain injury in the ED. The effectiveness and cost-effectiveness of the developed intervention is being evaluated in a cluster randomised trial, part of the Neurotrauma Evidence Translation (NET) program.

Similar content being viewed by others

Background

Guidance for developing complex interventions, such as those focussed on implementation, advocate the use of theory in the intervention development process [1]. It is argued that interventions are more likely to be effective if they target causal determinants of behaviour and behaviour change, and theory can be useful in gaining an understanding of these causal mechanisms [2]. In addition, there have been calls for better descriptions and reporting of implementation interventions to enable replication and refinement of interventions [3, 4]. Few studies report the rationale, process of development and detailed description of the intervention content, mode of delivery and the setting in which it is delivered to inform replication and/or refinement of interventions [5–7].

There are several approaches to the use of theory for developing interventions [2, 8–10], but there is currently no consensus on how best to select or apply theory. Multiple theories and theoretical frameworks of individual and organisational behaviour change exist, but choosing an appropriate theory can be challenging [9, 11–13]. Drawing on multiple relevant theories rather than a single theory is considered to facilitate a more comprehensive assessment of potential determinants of change and therefore an intervention that is more likely to be effective [9].

The Theoretical Domains Framework (TDF) [14, 15] is a comprehensive framework of 14 theoretical domains from 33 behaviour change theories and 128 constructs. It was developed using an expert consensus and validation process to identify an agreed set of theoretical domains that could be used when studying implementation and developing implementation interventions. The TDF has been successfully used in a wide range of settings, including the emergency department (ED) setting, to explore factors influencing clinical behaviour change and to design implementation interventions [16]. The ED environment is complex and has unique characteristics that can have an impact on its responsiveness to change, e.g. high staff turnover, lack of follow-up and a high number of decisions per unit of time [17].

Mild traumatic brain injury (mTBI) or concussion accounts for up to 90 % of patients who present to the ED with a traumatic brain injury (TBI) [18, 19] and has an incidence rate of between 100 and 300/100,000 inhabitants per year [20]. A recent study from the USA found that between the years 2006 and 2010, the rate of increase in TBI visits was eightfold greater than the rate of increase of total ED visits, and this increase was largely due to mTBI patients [21]. Mild TBI patients are predominately managed in the ED and discharged within hours [22]. While the majority will make a full recovery within a few weeks or months, approximately 15–25 % of patients will go on to have post-concussion symptoms, e.g. subjective, self-reported ongoing headaches and cognitive problems [23, 24]. A small minority (approximately 1 %) deteriorate and require neurosurgical intervention [25].

Evidence-based guideline recommendations are available to guide the care of patients with mTBI in the ED. However, studies indicate there is variability in management practices and care is often inconsistent with guideline recommendations [26–32]. The Neurotrauma Evidence Translation (NET) program is a 5-year knowledge translation program that aims to increase the uptake of research evidence to inform the care of patients who have sustained a TBI [33]. One of the program’s objectives is to systematically develop and evaluate a targeted, theory- and evidence-informed intervention to increase the uptake of evidence in the ED management of mTBI. The intervention will be implemented in EDs across the states of Australia and its effectiveness will be evaluated in a cluster randomised trial [34].

Previous implementation research undertaken in the ED setting has identified influential factors at the levels of the individual clinician, the environment and the organisation [35–37]. Although some organisational constructs are represented in the TDF (e.g. under the domains ‘Environmental Context and Resources’, ‘Social Influences’, ‘Social/Professional Role and Identity’ and ‘Behavioural Regulation’), further elaboration of the framework to include organisation-level influences has been suggested as a means of enhancing the usefulness of the framework [16]. Therefore, a conceptual model for considering potential factors influencing the organisational context of organisations was chosen to elaborate these domains. There are several frameworks available to explore the contextual factors influencing implementation of interventions in complex organisations such as the ED [38, 39]. Context can be defined as ‘influences which interact with each other, and interact with the implementation process’ [40]. The Model of Diffusion of Innovations in Service Organisations [41] was chosen as it was developed through a systematic review of the literature, covering 13 research areas in various disciplines (e.g. sociology, psychology, organisation and management), and the domains exploring organisational characteristics were comprehensive and deemed relevant for this setting. It identifies the main domains or areas in which factors influence the uptake and implementation of interventions in organisations. This model is only one way to investigate this issue but it is important to apply a model that has been developed from a strongly organisational perspective.

This paper describes the process of developing a targeted, theory- and evidence-informed intervention aiming to improve the management of mTBI in the ED, drawing on these two theoretical frameworks. It discusses the manner in which these frameworks were used in a complementary way to develop the intervention components and provides descriptions of the behaviour change techniques (BCTs) and modes of delivery used in the intervention and the causal processes targeted by the BCTs.

Methods

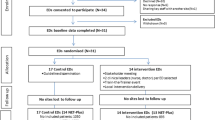

A stepped approach was used to develop the intervention (see Fig. 1) and is described in detail below. This approach was developed drawing on the methods outlined by French et al. [9], which was used to design an intervention to improve the management of low back pain in general practice [42].

Identify who needs to do what, differently

Identify or develop locally applicable, actionable evidence-based recommendations

In the absence of an up to date, locally relevant evidence-based guideline (EBG), a systematic search to identify guidelines relevant to the management of mTBI was undertaken and the quality of the identified EBGs was rated using the Appraisal of Guidelines Research and Evaluation (AGREE) Instrument [43]. Recommendations from guidelines that met our quality criteria were extracted from the EBGs and included in a recommendation matrix [32]. To determine the focus of our study, we identified strong evidence-based recommendations (i.e. grade A or B) in key clinical management areas (i.e. present in the majority of included EBGs). An additional search of the literature from the date of the last search of the most up to date EBG was undertaken to identify additional studies. Evidence overview tables were developed that incorporated the supporting evidence from the recommendation matrix and the additional studies. These tables were discussed at an international consensus meeting to agree upon the evidence statements. Eleven participants attended the meeting representing a range of organisations located in Australia, the USA and Canada including major trauma centres and/or foundations. All participants had a background in (clinical) research with all but three of the participants being clinically trained. Two local stakeholder meetings were then held in conjunction with relevant local clinical conferences in Melbourne, Australia to discuss the relevance of these evidence statements to the Australian ED setting, and to develop recommendations in the form of statements about who does what, when and how. The 1.5 h meetings were attended by 15 participants representing stakeholders in metropolitan and rural hospitals throughout Australia, in a variety of (clinical) roles [44].

Identify the evidence-practice gap

In order to quantify gaps between the recommendations agreed in ‘Identify or develop locally applicable, actionable evidence-based recommendations‘ section and current practice, two activities were undertaken: (i) a scoping search of the literature to identify studies conducted measuring practice patterns relevant to the management of mTBI patients in the ED, and (ii) a retrospective audit of the medical records of consecutive adult patients presenting with mTBI to the EDs of two inner-city hospitals in the Australian state of Victoria over a 2-month period (April to May 2011) [45].

Identify the barriers and enablers that need to be addressed using theoretical frameworks

Semi-structured qualitative interviews were conducted with a sample of ED staff in the Australian state of Victoria to explore barriers and enablers to practice change [46]. Using a topic guide, questions relating to the TDF were used to investigate each of the recommended clinical behaviours [14] and questions relating to the Model of Diffusion of Innovations in Service Organisations were used to explore the organisational context in which the management of mTBI and change occurs [41]. Interviews were recorded and recordings were transcribed verbatim and anonymised. The interview transcripts were coded using thematic content analysis according to theoretical domains. Important (i.e. salient) domains were identified according to how frequently they were mentioned and/or deemed to be of high importance by the researchers or participant [47].

Identify intervention components to address the modifiable barriers and enhance the enablers

Intervention components, that is, behaviour change techniques and modes of delivery, were identified as described below and in Fig. 1.

Identify potential behaviour change techniques and modes of delivery for each evidence-based recommendation

To select the behaviour change techniques (BCTs) most likely to bring about change for each recommended clinical behaviour, we mapped the important barriers and enablers, grouped by TDF domains (identified in ‘Identify the barriers and enablers that need to be addressed using theoretical frameworks‘ section), to appropriate BCTs using the matrix developed by Michie et al. [2]. The matrix links a taxonomy of BCTs to the theoretically derived theoretical domains that form the TDF and indicates which BCTs are likely to be effective in changing that particular domain. Additional techniques were identified from Cane et al. [48] that link BCTs from the BCT Taxonomy [49] to the refined TDF [15].

The BCTs were reviewed by the research team and potential modes of delivery were suggested. The BCTs and modes of delivery were reviewed in terms of feasibility and appropriateness for the local ED setting, informed by an analysis of the organisational context (see below).

Identify the implications of the analysis of organisational context on intervention components

Where factors derived from the analyses of organisational context were considered important and potentially modifiable, reviews/literature on specific theories and overviews of implementation interventions were consulted [41, 50–53] to identify intervention components that may be effective in targeting those factors. Other non-modifiable factors (moderators) were taken into consideration to maximise the likelihood that the intervention components were a good fit with the ED environment, e.g. influencing modes of delivery, duration of intervention components informing the choice between various BCTs. Implications of organisational context for intervention design were agreed in a research team meeting.

Identify evidence from systematic reviews of effects of implementation interventions to inform the selection of intervention components

Systematic reviews of interventions designed to improve healthcare systems and healthcare delivery published by the Cochrane Effective Practice and Organisation of Care (EPOC) Group [54] were searched in November 2012. Their findings, together with those from Grimshaw et al.’s overview of implementation interventions [55] were discussed in a research team meeting and intervention components were proposed. The overview provides a definition for each intervention, the likely mechanisms of action of interventions and comments on the practical delivery of interventions [55].

Identify feasibility, local relevance and acceptability of the intervention

Feasibility, local relevance and acceptability were assessed by the research team that included ED clinicians and behavioural scientists who used their experience to consider the practicality of delivery of the intervention components in the ED setting.

To facilitate reproducibility of the intervention, recommendations provided by the WIDER Group [3], TIDieR [4] and Proctor, et al. [6] were used to guide the development of descriptions of the intervention components. The following criteria were used to operationalise the intervention components: (1) characteristics of those delivering the intervention, (2) characteristics of the recipients (toward what or whom and at what level), (3) the setting (time and place of intervention), (4) intervention content, (5) mode of delivery, (6) intensity or dose (what frequency and intensity), (7) the duration (number of sessions, time) and (8) justification (theoretical, empirical or pragmatic).

Results

Identify who needs to do what, differently

Identify or develop locally applicable, actionable evidence-based recommendations

Six high-quality EBGs met the inclusion criteria and strong evidence-based recommendations were extracted. The quality of the EBGs and the extracted recommendations, along with the process of using these recommendations to develop locally applicable evidence-based recommendations, are described in detail elsewhere [32, 44]. Four target evidence-based recommendations were identified (see Table 1). To demonstrate the process of developing the intervention, the first of these recommendations will be used as an example throughout the paper: ‘post-traumatic amnesia (PTA) should be prospectively assessed in the ED using a validated tool’.

Identify the evidence-practice gap

The scoping search of the literature identified studies from the UK, Ireland, USA, Canada and Norway that provided evidence of inter- and intra-hospital variability in the management of mTBI in the ED and the recommended clinical behaviours [26–31]. There were no published studies identified that reported rates of PTA assessment for mTBI.

The medical files of 206 consecutive patients presenting with mTBI at two EDs in the Australian state of Victoria were audited [45]. For the recommended behaviour, prospectively assessing patients for PTA using a validated tool, the rates of assessment of PTA in adults with mTBI were 0 % (95 % CI 0 to 14 %, n = 24) in one hospital and 31 % (95 % CI 24 to 39 %, n = 164) for the second [34, 45].

Identify the barriers and enablers that need to be addressed using theoretical frameworks

Interviews with 42 ED staff from 13 hospitals were conducted between November 2010 and May 2011. The detailed findings from the interviews are described separately [46]. The key barriers and enablers for prospectively assessing patients for PTA using a validated tool were associated with six of the TDF domains ‘Knowledge’, ‘Environmental context and resources’, ‘Skills’, ‘Beliefs about consequences’, ‘Social/professional role and identity’ and ‘Beliefs about capabilities’ (see Table 2). Key organisational factors in relation to the management of this patient group, organising change in general and the organisational context in which the four recommended clinical behaviours take place are presented in Table 3.

Identify intervention components to address the modifiable barriers and enhance the enablers

Identify potential behaviour change techniques and modes of delivery for each evidence-based recommendation

Fourteen BCTs were selected to target the modifiable barriers and enhance the enablers for assessing PTA using a validated tool (grouped into six of the TDF domains). Table 4 provides details of the mapping process for selecting BCTs and the subsequent intervention components. For example, for the domain ‘Knowledge’, the BCTs ‘Information regarding behaviour, outcome’, ‘Antecedents’, ‘Health consequences’ and ‘Feedback on behaviour’ were advocated. Of the intervention components suggested, the provision of ‘Feedback on behaviour’ using audit data was not deemed feasible (see ‘Identify feasibility, local relevance and acceptability of the intervention‘ section). A summary of the intervention components that were decided upon for the PTA behaviour is included in Table 5 and illustrated in Fig. 2.

Identify the implications of the analysis of organisational context on intervention components

Table 3 describes the implications of taking into account important factors from the analysis of the organisational context. Some overarching intervention components such as the stakeholder meeting and recruitment of local opinion leaders to deliver local training and the provision of reimbursement were proposed to overcome important organisational barriers and enhance enablers. These components were designed to address factors relevant to more than one clinical behaviour and, more broadly, to increase the compatibility of the intervention with the organisational setting. For instance, the primary reason for selecting local stakeholder meetings was to enhance organisational buy-in, e.g. provide the ED senior leadership with an opportunity to express commitment; to start the conversation with local stakeholders such as neuropsychologists and/or occupational therapists (as changes in ED practice may influence others in the hospital); to discuss how the recommended clinical behaviours fit with their current practices (e.g. protocols or pathways as relevant) and whether they foresaw any potential hurdles in introducing the intervention from an organisational point of view. The stakeholder meeting was also a first opportunity to introduce some of the BCTs selected to address TDF factors in relation to each recommended clinical behaviour (e.g. persuasive messages). Other organisational factors influenced decisions regarding the mode of delivery or feasibility of decisions (e.g. the high staff turnover rate in combination with an environment that is stretched means that local sessions need to be very brief, so they can be delivered frequently, and back-up materials (e.g. presentations with spoken script) need to be available for (new) staff to watch outside scheduled training moments. Fig. 2 illustrates how the organisational factors influenced the selection of intervention components targeting the assessment of PTA.

Identify evidence from systematic reviews of effects of implementation interventions to inform the selection of intervention components

Six Cochrane EPOC reviews were identified that focused on interventions to change practitioner behaviour and contained interventions deemed to be effective [56–61]. Table 6 includes the key findings from the reviews, the interventions’ hypothesised mechanisms of action, the practicalities of implementing them and the intervention components that were proposed by the research team when considering the findings of the reviews in relation to this implementation problem.

Identify feasibility, local relevance and acceptability of the intervention

The feasibility of delivering each of the proposed intervention components within the context of the ED was discussed by the research team, e.g. providing training and education in the ED with a high turnover of staff. The discussions resulted in the identification of five intervention components: local stakeholder meetings, identification of local opinion leader team (one medical and one nurse in each site), a train-the-trainer workshop for identified local opinion leaders, local training workshops facilitated by the trained local opinion leaders and the provision of tools and materials to prompt recommended behaviours. Several intervention components were deemed not feasible for implementation in the ED setting due to the limited time and resources available. These included changes to the electronic patient record system whereby a patient cannot be discharged without a patient information leaflet being printed out and the provision of regular audit and feedback data to clinical staff. Although there is evidence that regular audit and feedback can lead to improvements in professional performance [59], the outcomes of interest (including the primary outcome for the cRCT) are not routinely collected, and it was not feasible to deliver across the 34 included EDs. Table 7 provides details of the intervention components and how they were operationalised. Fig. 2 shows how the two frameworks influenced the design of the intervention for the recommended PTA behaviour, including details of where each of the intervention components originated and provides a justification for its inclusion, e.g. as part of the mapping process or evidence from EPOC reviews. The figure also includes overarching components and content (i.e. that apply not just to PTA, such as the stakeholder meetings and opinion leaders, which were identified as important to ensure an intervention that was suited to the organisational setting, rather than just targeting individual clinicians with behaviour-specific techniques).

Discussion

This paper illustrates a systematic, theory- and evidence-informed approach to developing an intervention that aims to improve the care of mTBI patients in the ED, that was informed by two theoretical frameworks: the TDF and the Model of Diffusion of Innovations in Service Organisations. Four evidence-based recommendations were identified to improve the care of this patient group, and the intervention components targeting the PTA behaviour consisted of 14 behaviour change techniques and addressed 6 TDF domains and 5 organisational domains. The modes of delivery were informed by six Cochrane reviews. There were five intervention components.

The TDF is frequently being used by researchers to explore clinical behaviour change and develop implementation interventions. It covers a range of behavioural influences including capability, motivation and opportunity; further elaboration of the domains to include organisation-level influences has been suggested [16]. It is recommended that studies targeting multiple levels (e.g. clinician and organisational) should draw upon multiple theories [62]. The benefit of studying change at the organisational level using organisational level theory, to complement the analyses regarding each recommended behaviour using the TDF, is that it facilitates exploration of the organisational context in greater detail and facilitates the inclusion of intervention components to directly target these influencing factors. There are limited practical examples in the literature of how to use theoretical frameworks when developing implementation interventions and this is, to our knowledge, the only study in the ED setting that has explicitly demonstrated how to use multiple theoretical frameworks to explore behaviour change and use these data to identify BCTs and develop intervention components.

The content of the intervention was designed to target hypothesised influences on behaviour and organisational change. This was achieved by selecting overarching strategies that were designed to address some of the organisational factors and/or maximise the likelihood that the intervention was fit for an organisational setting (e.g. stakeholder meetings and local opinion leaders), in addition to specifying BCTs relevant and tailored to each particular clinical behaviour. Synthesised evidence of professional behaviour change interventions and practical considerations of the mode of delivery informed development alongside theory and increased the likelihood that the end product was evidence-informed, feasible to deliver and acceptable to the ED community [63].

The core components of the intervention, the training of local opinion leaders to deliver local training workshops, addressed the majority of the identified facilitators of behaviour change using the TDF. The TDF domain ‘Environmental context and resources’ was not covered by the training components, and this domain was addressed with the provision of online and printed tools and materials, e.g. PTA assessment sheets and point of care reminder stickers. Intervention components, such as the involvement of senior leaders in local stakeholder meetings to create buy-in and the nomination of ‘multidisciplinary’ local opinion leaders to provide regular, brief training sessions in the ED, were chosen to target key organisational factors. There were, however, several intervention components that were deemed as not feasible for the ED setting. A major strength of this study, and the process used, is the documentation of decisions, throughout the process, of why intervention components were chosen and why they may have been modified. This enables researchers to understand the reasons for selecting content.

On conceptual grounds, there is reason to propose that the intervention, being based on robust theories and methods, is more likely to be effective than interventions that are not based on theory and evidence. However, it requires a cluster randomised controlled trial (cRCT) to address the empirical question as to whether this robust process leads to measurable effectiveness. The effectiveness of this intervention to improve care of patients with mTBI will be evaluated in a cluster randomised controlled trial [34] and outcome measures of behaviour change and factors thought to mediate the effect of the intervention along the proposed pathway of change will be assessed. These include mediators of behaviour change (e.g. beliefs about capabilities, beliefs about consequences), measures of practitioner behaviour (e.g. primary practitioner outcome is appropriate PTA screening), patient outcomes and cost. The evaluation of the factors along the causal pathway will be complemented by other components that form part of a process evaluation. The details of these outcomes and the process evaluation measures are reported separately [34]. Implementation research is a cumulative science, and this intervention is in the process of a robust evaluation that will add to the evidence of the effectiveness of theory-informed interventions to improve clinical practice.

Although there have been a number of publications on the development of theory-informed interventions to improve clinical practice [63–66], to our knowledge there have been few studies of this kind undertaken in the ED setting. A theory-informed intervention to implement two paediatric clinical pathways in the ED is being developed by Jabbour et al., but this is at the protocol stage [67]. Gould et al. are developing two theoretically enhanced audit and feedback interventions to improve the uptake of evidence-based transfusion practice using the TDF in combination with the Consolidated Framework for Implementation Research (CFIR) [64, 68]. The study is not focussed in the ED setting and is at the protocol stage. The research detailed in this paper may offer insights and guidance to those wanting to design implementation interventions in the ED setting and to those interested in using multiple theoretical frameworks, in addition to evidence and feasibility considerations in the design of implementation interventions.

One of the criticisms of past implementation research is the difficulty of understanding what intervention components were selected and their hypothesised mechanism of action [69]. This study followed a systematic process detailing how the intervention was developed and providing detailed descriptions of the intervention content. The intervention components have been described according to the WIDER and TIDieR Guidance [3, 4] and in terms of BCTs and modes of delivery [49, 66]. This differentiation between intervention content (BCTs) and models of delivery enables other researchers to explore the effectiveness of the BCTs when a different mode of delivery is applied [69].

The recent validation and refinement of the TDF domains has strengthened the rationale for its methodology and use in implementation research [15]. The validation of the TDF was published after the conduct of the interviews and therefore the original TDF was used to explore barriers and enablers with ED staff [14]. Although the BCTs were mapped to the original TDF domains, this process was supplemented with the BCTs proposed in the validation paper [48] linking the BCT Taxonomy v1 [49] to the refined TDF [15]. This taxonomy was recently updated to include 93 BCTs and 14 domains [66].

If theory is poorly operationalised, it will be less useful in identifying factors that influence outcomes in specified settings. Thus, an intervention may be ineffective due to the research team’s operationalisation of theory when developing the intervention [8]. This is potentially a methodological limitation of this study; although we used a systematic and replicable process to operationalise the theoretical domains in terms of appropriate intervention components, the process was conducted by just one research team. There is, however, little research on how best to operationalise theory in the context of intervention development and selecting or designing intervention components [70]. The research team did, however, include a wide range of ED clinicians, behavioural scientists and evidence-based researchers to incorporate a breadth of experience.

Conclusions

This paper provides a systematic, theory- and evidence-informed approach to developing an intervention aiming to change professional practice in the ED setting. Theoretical frameworks, evidence-based behaviour change techniques, evidence about the effects of modes of delivery (EPOC systematic reviews) and feasibility information were systematically brought together to develop an intervention that aims to improve the management of mTBI patients in the ED. This study demonstrated the use of the TDF in addition to a model designed to explore organisational factors to develop a theory-informed intervention in a complex organisational setting. The effectiveness of this intervention will be evaluated in a large national cluster randomised controlled trial which forms part of a larger program of work called the Neurotrauma Evidence Translation (NET) program [33, 34].

Abbreviations

- mTBI:

-

Mild traumatic brain injury

- ED:

-

Emergency department

- TDF:

-

Theoretical domains framework

- PTA:

-

Post-traumatic amnesia

- NET:

-

Neurotrauma evidence translation

- BCT:

-

Behaviour change techniques

- EBG:

-

Evidence-based guideline

- EPOC:

-

Effective practice and organisation of care

References

Craig P, Dieppe P, Macintyre S, Michie S, Nazareth I, Petticrew M. Developing and evaluating complex interventions: the new Medical Research Council guidance. BMJ. 2008;337:a1655.

Michie S, Johnston M, Francis JJ, Hardeman W, Eccles M. From theory to intervention: mapping theoretically derived behavioural determinants to behaviour change techniques. Appl Psychol. 2008;57:660–80.

WIDER recommendations to improve reporting of the content of behaviour change interventions. [http://www.implementationscience.com/content/supplementary/1748-5908-7-70-s4.pdf]

Hoffmann TC, Glasziou PP, Boutron I, Milne R, Perera R, Moher D, et al. Better reporting of interventions: template for intervention description and replication (TIDieR) checklist and guide. BMJ. 2014;348:g1687.

Hoffmann TC, Erueti C, Glasziou PP. Poor description of non-pharmacological interventions: analysis of consecutive sample of randomised trials. BMJ. 2013;347:f3755.

Proctor EK, Powell BJ, McMillen JC. Implementation strategies: recommendations for specifying and reporting. Implement Sci. 2013;8:139.

Lloyd JJ, Logan S, Greaves CJ, Wyatt KM. Evidence, theory and context–using intervention mapping to develop a school-based intervention to prevent obesity in children. Int J Behav Nutr Phys Act. 2011;8:73.

(ICEBeRG) TICEtBRG. Designing theoretically-informed implementation interventions. Implement Sci. 2006;1:4.

French SD, Green SE, O’Connor DA, McKenzie JE, Francis JJ, Michie S, et al. Developing theory-informed behaviour change interventions to implement evidence into practice: a systematic approach using the theoretical domains framework. Implement Sci. 2012;7:38.

Michie S, van Stralen MM, West R. The behaviour change wheel: a new method for characterising and designing behaviour change interventions. Implement Sci. 2011;6:42.

Lippke S, Ziegelmann JP. Theory-based health behavior change: developing, testing, and applying theories for evidence-based interventions. Appl Psychol. 2008;57:698–716.

Grol RP, Bosch MC, Hulscher ME, Eccles MP, Wensing M. Planning and studying improvement in patient care: the use of theoretical perspectives. Milbank Q. 2007;85:93–138.

Michie S, West R, Campbell R, Brown J, Gainforth H. ABC of behaviour change theories. Sutton, UK: Silverback Publishing; 2014.

Michie S, Johnston M, Abraham C, Lawton R, Parker D, Walker A. Making psychological theory useful for implementing evidence based practice: a consensus approach. Qual Saf Health Care. 2005;14:26–33.

Cane J, O’Connor D, Michie S. Validation of the theoretical domains framework for use in behaviour change and implementation research. Implement Sci. 2012;7:37.

Francis JJ, O’Connor D, Curran J. Theories of behaviour change synthesised into a set of theoretical groupings: introducing a thematic series on the theoretical domains framework. Implement Sci. 2012;7:35.

Brehaut JC, Hamm R, Majumdar S, Papa F, Lott A, Lang E. Cognitive and social issues in emergency medicine knowledge translation: a research agenda. Acad Emerg Med. 2007;14:984–90.

Cassidy JD, Carroll LJ, Peloso PM, Borg J, von Holst H, Holm L, et al. Incidence, risk factors and prevention of mild traumatic brain injury: results of the WHO collaborating centre task force on mild traumatic brain injury. J Rehabil Med. 2004;43S:28–60.

Wasserberg J. Treating head injuries. BMJ. 2002;325:454–5.

Holm L, Cassidy JD, Carroll LJ, Borg J. Summary of the WHO collaborating centre for neurotrauma task force on mild traumatic brain injury. J Rehabil Med. 2005;37:137–41.

Marin JR, Weaver MD, Yealy DM, Mannix RC. Trends in visits for traumatic brain injury to emergency departments in the United States. JAMA. 2014;311:1917–9.

Thurman D, Guerrero J. Trends in hospitalization associated with traumatic brain injury. JAMA. 1999;282:954–7.

Ponsford J, Willmott C, Rothwell A, Cameron P, Kelly AM, Nelms R, et al. Factors influencing outcome following mild traumatic brain injury in adults. J Int Neuropsychol Soc. 2000;6:568–79.

Faux S, Sheedy J. A prospective controlled study in the prevalence of posttraumatic headache following mild traumatic brain injury. Pain Med. 2008;9:1001–11.

Stiell IG, Wells GA, Vandemheen K, Clement C, Lesiuk H, Laupacis A, et al. The Canadian CT Head Rule for patients with minor head injury. Lancet. 2001;357:1391–6.

Bazarian JJ, McClung J, Cheng YT, Flesher W, Schneider SM. Emergency department management of mild traumatic brain injury in the USA. Emerg Med J. 2005;22:473–7.

Ingebrigtsen T, Romner B. Management of minor head injuries in hospitals in Norway. Acta Neurol Scand. 1997;95:51–5.

Stiell IG, Wells GA, Vandemheen K, Laupacis A, Brison R, Eisenhauer MA, et al. Variation in ED use of computed tomography for patients with minor head injury. Ann Emerg Med. 1997;30:14–22.

Kerr J, Smith R, Gray S, Beard D, Robertson CE. An audit of clinical practice in the management of head injured patients following the introduction of the Scottish Intercollegiate Guidelines Network (SIGN) recommendations. Emerg Med J. 2005;22:850–4.

Heskestad B, Baardsen R, Helseth E, Ingebrigtsen T. Guideline compliance in management of minimal, mild, and moderate head injury: high frequency of noncompliance among individual physicians despite strong guideline support from clinical leaders. J Trauma. 2008;65:1309–13.

Peachey T, Hawley CA, Cooke M, Mason L, Morris R. Minor head injury in the Republic of Ireland: evaluation of written information given at discharge from emergency departments. Emerg Med J. 2010;28(8):707–8.

Tavender EJ, Bosch M, Green S, O’Connor D, Pitt V, Phillips K, et al. Quality and consistency of guidelines for the management of mild traumatic brain injury in the emergency department. Acad Emerg Med. 2011;18:880–9.

Green SE, Bosch M, McKenzie JE, O’Connor DA, Tavender EJ, Bragge P, et al. Improving the care of people with traumatic brain injury through the Neurotrauma Evidence Translation (NET) program: protocol for a program of research. Implement Sci. 2012;7:74.

Bosch M, McKenzie JE, Mortimer D, Tavender EJ, Francis JJ, Brennan SE, et al. Implementing evidence-based recommended practices for the management of patients with mild traumatic brain injuries in Australian emergency care departments: study protocol for a cluster randomised controlled trial. Trials. 2014;15:281.

Toma A, Bensimon CM, Dainty KN, Rubenfeld GD, Morrison LJ, Brooks SC. Perceived barriers to therapeutic hypothermia for patients resuscitated from cardiac arrest: a qualitative study of emergency department and critical care workers. Crit Care Med. 2009;38:504–9.

Scott SD, Osmond MH, O’Leary KA, Graham ID, Grimshaw J, Klassen T. Barriers and supports to implementation of MDI/spacer use in nine Canadian pediatric emergency departments: a qualitative study. Implement Sci. 2009;4:65.

Bessen T, Clark R, Shakib S, Hughes G. A multifaceted strategy for implementation of the Ottawa ankle rules in two emergency departments. BMJ. 2009;339:b3056.

Flottorp SA, Oxman AD, Krause J, Musila NR, Wensing M, Godycki-Cwirko M, et al. A checklist for identifying determinants of practice: a systematic review and synthesis of frameworks and taxonomies of factors that prevent or enable improvements in healthcare professional practice. Implement Sci. 2013;8:35.

Tabak RG, Khoong EC, Chambers DA, Brownson RC. Bridging research and practice: models for dissemination and implementation research. Am J Prev Med. 2012;43:337–50.

Ovretveit JC, Shekelle PG, Dy SM, McDonald KM, Hempel S, Pronovost P, et al. How does context affect interventions to improve patient safety? An assessment of evidence from studies of five patient safety practices and proposals for research. BMJ Qual Saf. 2011;20:604–10.

Greenhalgh T, Robert G, Macfarlane F, Bate P, Kyriakidou O. Diffusion of innovations in service organizations: systematic review and recommendations. Milbank Q. 2004;82:581–629.

French SD, McKenzie JE, O’Connor DA, Grimshaw JM, Mortimer D, Francis JJ, et al. Evaluation of a theory-informed implementation intervention for the management of acute low back pain in general medical practice: the IMPLEMENT cluster randomised trial. PLoS One. 2013;8:e65471.

AGREE instrument. [http://www.agreetrust.org/]

Bosch M, Tavender E, Bragge P, Gruen R, Green S. How to define ‘best practice’ for use in Knowledge Translation research: a practical, stepped and interactive process. J Eval Clin Pract. 2012;19(5):763–8.

Goh M. Mild traumatic brain injury in the emergency department: an audit of practice. Melbourne: Monash University, Central Clinical School; 2012.

Tavender EJ, Bosch M, Gruen RL, Green SE, Knott J, Francis JJ, et al. Understanding practice: the factors that influence management of mild traumatic brain injury in the emergency department-a qualitative study using the theoretical domains framework. Implement Sci. 2014;9:8.

Buetow S. Thematic analysis and its reconceptualization as ‘saliency analysis’. J Health Serv Res Policy. 2009;15:123–5.

Cane J, Richardson M, Johnston M, Ladha R, Michie S. From lists of behaviour change techniques (BCTs) to structured hierarchies: comparison of two methods of developing a hierarchy of BCTs. Br J Health Psychol. 2014;20(1):130–50.

Michie S, Richardson M, Johnston M, Abraham C, Francis J, Hardeman W, et al. The behavior change technique taxonomy (v1) of 93 hierarchically clustered techniques: building an international consensus for the reporting of behavior change interventions. Ann Behav Med. 2013;46:81–95.

Colquhoun H, Leeman J, Michie S, Lokker C, Bragge P, Hempel S, et al. Towards a common terminology: a simplified framework of interventions to promote and integrate evidence into health practices, systems, and policies. Implement Sci. 2014;9:51.

Leeman J, Baernholdt M, Sandelowski M. Developing a theory-based taxonomy of methods for implementing change in practice. J Adv Nurs. 2007;58:191–200.

Mazza D, Bairstow P, Buchan H, Chakraborty SP, Van Hecke O, Grech C, et al. Refining a taxonomy for guideline implementation: results of an exercise in abstract classification. Implement Sci. 2013;8:32.

Powell BJ, McMillen JC, Proctor EK, Carpenter CR, Griffey RT, Bunger AC, et al. A compilation of strategies for implementing clinical innovations in health and mental health. Med Care Res Rev. 2011;69:123–57.

The Cochrane Library. In: Book The Cochrane Library. City: Wiley; 2014. Issue 3

Grimshaw JM, Eccles MP, Lavis JN, Hill SJ, Squires JE. Knowledge translation of research findings. Implement Sci. 2014;7:50.

Forsetlund L, Bjorndal A, Rashidian A, Jamtvedt G, O’Brien MA, Wolf F, et al. Continuing education meetings and workshops: effects on professional practice and health care outcomes. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2009;3:CD003030.

Flodgren G, Parmelli E, Doumit G, Gattellari M, O’Brien MA, Grimshaw J, et al. Local opinion leaders: effects on professional practice and health care outcomes. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2011;8:CD000125.

Giguere A, Legare F, Grimshaw J, Turcotte S, Fiander M, Grudniewicz A, et al. Printed educational materials: effects on professional practice and healthcare outcomes. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2012;10:CD004398.

Ivers N, Jamtvedt G, Flottorp S, Young JM, Odgaard-Jensen J, French SD, et al. Audit and feedback: effects on professional practice and healthcare outcomes. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2012;6:CD000259.

Shojania KG, Jennings A, Mayhew A, Ramsay CR, Eccles MP, Grimshaw J. The effects of on-screen, point of care computer reminders on processes and outcomes of care. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2009;3:CD001096.

O’Brien MA, Rogers S, Jamtvedt G, Oxman AD, Odgaard-Jensen J, Kristoffersen DT, et al. Educational outreach visits: effects on professional practice and health care outcomes. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2007;17:CD000409.

Foy R, Ovretveit J, Shekelle PG, Pronovost PJ, Taylor SL, Dy S, et al. The role of theory in research to develop and evaluate the implementation of patient safety practices. BMJ Qual Saf. 2011;20:453–9.

Porcheret M, Main C, Croft P, McKinley R, Hassell A, Dziedzic K. Development of a behaviour change intervention: a case study on the practical application of theory. Implement Sci. 2014;9:42.

Gould NJ, Lorencatto F, Stanworth SJ, Michie S, Prior ME, Glidewell L, et al. Application of theory to enhance audit and feedback interventions to increase the uptake of evidence-based transfusion practice: an intervention development protocol. Implement Sci. 2014;9:92.

Squires JE, Grimshaw JM, Taljaard M, Linklater S, Chasse M, Shemie SD, et al. Design, implementation, and evaluation of a knowledge translation intervention to increase organ donation after cardiocirculatory death in Canada: a study protocol. Implement Sci. 2014;9:80.

Michie S, Atkins L, West R. The behaviour change wheel: a guide to designing interventions. London, UK: Silverback Publishing; 2014.

Jabbour M, Curran J, Scott SD, Guttman A, Rotter T, Ducharme FM, et al. Best strategies to implement clinical pathways in an emergency department setting: study protocol for a cluster randomized controlled trial. Implement Sci. 2013;8:55.

Damschroder LJ, Aron DC, Keith RE, Kirsh SR, Alexander JA, Lowery JC. Fostering implementation of health services research findings into practice: a consolidated framework for advancing implementation science. Implement Sci. 2009;4:50.

Hrisos S, Eccles M, Johnston M, Francis J, Kaner EF, Steen N, et al. Developing the content of two behavioural interventions: using theory-based interventions to promote GP management of upper respiratory tract infection without prescribing antibiotics #1. BMC Health Serv Res. 2008;8:11.

Kolehmainen N, Francis JJ. Specifying content and mechanisms of change in interventions to change professionals’ practice: an illustration from the Good Goals study in occupational therapy. Implement Sci. 2012;7:100.

Grimshaw JM, Eccles MP, Lavis JN, Hill SJ, Squires JE. Knowledge translation of research findings. Implement Sci. 2012;7:50.

Acknowledgements

The NET Program is funded by the Victorian Transport Accident Commission, Australia. EJT is supported by an Australian Postgraduate Award, Australian National Health and Medical Research Council. DOC is supported by an Australian National Health and Medical Research Council Public Health Fellowship. RLG is supported by a Practitioner Fellowship from the Australian National Health and Medical Research Council.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Additional information

Competing interests

Denise O’Connor and Susan Michie are Associate Editors for Implementation Science. All decisions on this manuscript were made independently by another editor. All other authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Authors’ contributions

EJT/MB drafted the manuscript. SG/RG/DOC conceived the study. SM/JF provided behavioural science input into interview interpretation and intervention design. All authors revised the manuscript for important intellectual content and gave final approval of the version to be published.

Rights and permissions

This article is published under an open access license. Please check the 'Copyright Information' section either on this page or in the PDF for details of this license and what re-use is permitted. If your intended use exceeds what is permitted by the license or if you are unable to locate the licence and re-use information, please contact the Rights and Permissions team.

About this article

Cite this article

Tavender, E.J., Bosch, M., Gruen, R.L. et al. Developing a targeted, theory-informed implementation intervention using two theoretical frameworks to address health professional and organisational factors: a case study to improve the management of mild traumatic brain injury in the emergency department. Implementation Sci 10, 74 (2015). https://doi.org/10.1186/s13012-015-0264-7

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/s13012-015-0264-7