Abstract

Background

There is little study of lifetime trauma exposure among individuals engaged in medication treatment for opioid use disorder (MOUD). A multisite study provided the opportunity to examine the prevalence of lifetime trauma and differences by gender, PTSD status, and chronic pain.

Methods

A cross-sectional study examined baseline data from participants (N = 303) enrolled in a randomized controlled trial of a mind–body intervention as an adjunct to MOUD. All participants were stabilized on MOUD. Measures included the Trauma Life Events Questionnaire (TLEQ), the Brief Pain Inventory (BPI), and the Posttraumatic Stress Disorder Checklist (PCL-5). Analyses involved descriptive statistics, independent sample t-tests, and linear and logistic regression.

Results

Participants were self-identified as women (n = 157), men (n = 144), and non-binary (n = 2). Fifty-seven percent (n = 172) self-reported chronic pain, and 41% (n = 124) scored above the screening cut-off for PTSD. Women reported significantly more intimate partner violence (85%) vs 73%) and adult sexual assault (57% vs 13%), while men reported more physical assault (81% vs 61%) and witnessing trauma (66% vs 48%). Men and women experienced substantial childhood physical abuse, witnessed intimate partner violence as children, and reported an equivalent exposure to accidents as adults. The number of traumatic events predicted PTSD symptom severity and PTSD diagnostic status. Participants with chronic pain, compared to those without chronic pain, had significantly more traumatic events in childhood (85% vs 75%).

Conclusion

The study found a high prevalence of lifetime trauma among people in MOUD. Results highlight the need for comprehensive assessment and mental health services to address trauma among those in MOUD treatment.

Trial registration

NCT04082637.

Similar content being viewed by others

Explore related subjects

Discover the latest articles, news and stories from top researchers in related subjects.Introduction

A growing body of literature documents the high prevalence of trauma exposure and PTSD among individuals with substance use disorders (SUD) [1, 2], with rates of co-occurring post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD) ranging from 33–50% [3]. However, with the opioid overdose epidemic, more trauma-related research is needed about lifetime trauma exposure among persons engaged in treatment with medication for opioid use disorder [4]. Medication for Opioid Use Disorder (MOUD) involves pharmacological treatment with buprenorphine or methadone to stabilize individuals with opioid dependence and decrease the potential for opioid misuse. These medications are associated with substantial reductions in overdose mortality [5]. This study examines the prevalence of lifetime trauma among individuals who are engaged in MOUD, particularly those stabilized on buprenorphine and methadone, to provide insights into the needs of this population, critical for improving integrative and comprehensive care for those engaged in MOUD.

Numerous studies have consistently shown a strong correlation between lifetime trauma and opioid use disorder [6]. This is especially relevant for individuals undergoing medication opioid use disorder treatment (MOUD), as they may have experienced various traumatic events, such as childhood trauma, interpersonal trauma, or traumatic accidents across their lifespan that have implications for treatment [7, 8]. It is crucial to understand these trauma profiles to tailor interventions and enhance treatment outcomes, involving assessment of lifetime trauma among those engaged in MOUD to deliver effective and comprehensive care.

An examination of traumatic events across the lifespan allows for differentiation between types of traumatic experiences (e.g., interpersonal, non-interpersonal, childhood), as well as the opportunity to examine related sex/gender differences and the relationship to PTSD symptoms, all of which are crucial for understanding the impact of trauma on any health condition or population [9]. For example, intimate interpersonal trauma is significantly more likely to be associated with symptoms of PTSD when compared to non-interpersonal trauma and non-intimate interpersonal trauma (e.g., physical assaults perpetrated by non-intimates) [10], and there is a significant relationship between the number of traumatic events and the development of PTSD [11]. Also, the potential health consequences of childhood trauma are increasingly evident. Systematic reviews consistently show a link between exposure to childhood violence and substance use disorder [12], with a 73% increased risk for SUD if there is a history of sexual abuse in childhood and a 74% increased risk if there is a history of physical abuse in childhood [13]. Sexual trauma is more prevalent among women than men. Women with a history of sexual trauma are at increased risk for SUD compared to men [13] and have specific treatment-related needs due to the type of trauma endured and its impact on mental health [14].

In research specific to trauma for those with opioid use disorder (OUD) (N = 20,522), a recent systematic review examining child maltreatment demonstrated the high prevalence of childhood physical abuse in 43% of the total sample and significantly more childhood sexual abuse among women (41%) compared to men (16%) [15]. Studies specific to examining trauma among those treated with MOUD have been relatively limited in scope and/or small in sample size. For example, one study (N = 919) examined interpersonal trauma only (physical, sexual, or emotional abuse) and found that 23% reported sexual abuse, 43% physical abuse, and 58% emotional abuse and that there were no differences by gender on any of these categories [16]. Unfortunately, this study by Powers did not distinguish whether the traumatic events occurred in childhood or as adults. Another study (N = 36) examined both interpersonal and non-interpersonal types of trauma (e.g., accidents, natural disasters) and found both to significantly predict OUD [6]. A third study (N = 135) examined current trauma only (over period of last 12 months) among those engaged in MOUD and found that more than one third reported interpersonal trauma (combining reported interpersonal traumas such as intimate partner violence, sexual assault, physical assault) and found similar overall rates among men (36%) and women (40%) [17].

Chronic pain is a co-occurring condition common among people with OUD, occurring in approximately two-thirds of patients [18, 19], and there is established high comorbidity between PTSD and chronic pain among individuals engaged in MOUD [20, 21]. While having chronic pain is not associated with return to nonprescribed use among those with MOUD [22, 23], it is a risk factor for return to nonprescribed use among those with highly volatile pain or severe pain [23,24,25]. Prior research demonstrates that trauma exposure is associated with an increased risk of developing chronic pain [1, 2], defined as persistent pain lasting for at least three months that adversely affects the function or well-being of the individual [26]. In addition, individuals with a trauma history are approximately three times more likely to develop a chronic pain condition than those without a trauma history [27]. Within the population of individuals affected by chronic pain, individuals with a trauma history report more intense pain [28, 29], greater affective distress, and a higher disability [30, 31] than individuals without a trauma history. Thus, it is highly relevant to examine the relationship between lifetime trauma exposure and chronic pain in this population.

As noted above, the type of traumatic experience appears to matter; specifically, the type of traumatic experience appears to be differentially associated with the development of chronic pain. The relationship between exposure to non-interpersonal trauma (e.g., traumatic accidents) and the development of chronic pain is well-established in individuals with and without SUD, with research demonstrating that accident-related pain is associated with greater pain severity and related disability in those with vs. without SUD [32]. The relationship between exposure to interpersonal trauma, childhood trauma in particular, and the development of chronic pain has also been established in the general population [33,34,35], replicated in SUD populations [36] and documented in OUD populations [37,38,39,40,41]. However, in most studies examining chronic pain or OUD, childhood trauma exposure has been defined and limited to single types of childhood abuse or neglect [38, 42]. Different types of trauma (e.g., interpersonal, non-interpersonal, adult and/or child, etc.) have yet to be investigated among persons with OUD. Doing so may illuminate important risk factors for those with co-occurring chronic pain and OUD [43].

The purpose of this study is to comprehensively examine lifetime trauma exposure among individuals engaged in treatment with MOUD. The four aims of this study are to: 1) examine the prevalence of different types of trauma exposure among individuals in MOUD; 2) identify gender differences in lifetime trauma exposure; 3) examine whether the number of traumatic events predicts PTSD symptom severity, and 4) compare types of trauma exposure among those with and without chronic pain.

Method

Study design, setting and enrollment

A National Center for Complementary and Integrated Health (NCCIH)-funded randomized controlled trial to examine mindful body awareness training in individuals engaged in MOUD treatment provided the opportunity to examine the prevalence of self-reported lifetime trauma exposure and differences in trauma exposure by gender and among those with and without chronic pain. This study received approval from the Human Subjects Institutional Review Board of a university in the northwestern United States. Data for this project was collected at baseline, prior to randomization to study treatment groups.

Study participants were recruited from six community clinics in urban and rural settings that offer outpatient MOUD in Washington State. Five out of six clinics prescribed buprenorphine and one prescribed methadone for MOUD. Three clinics were primary care clinics with embedded buprenorphine programs using a nurse-care model [44], one was a mental health clinic offering buprenorphine treatment, one was a MOUD-only community clinic offering buprenorphine, and one was an opioid treatment program offering methadone. All clinics had mental health services available on-site, although access to services varied and was often limited. The overall level of MOUD care was comparable with all sites offering regular 1:1 appointments with a medical provider (nurse and/or physician) with an emphasis on attention to medical and other social service supports needed; the exception was the methadone clinic where regular appointments were with a counselor who focused on substance use counseling and social service support.

Recruitment was based on referral of interested and potentially eligible patients by clinic staff (i.e., nurses, physicians, and counselors). The Research Coordinator at each clinical site screened for eligibility and enrolled patients interested in study participation. Screening criteria aimed to select patients with adequate treatment engagement and clinical stability to participate in the mindful body awareness intervention sessions. Evidence of medication dose stability: buprenorphine/naloxone was defined as at least 30 days of medication treatment and an appointment frequency of less than once weekly. For methadone, this was defined as at least 90 days in treatment with a minimum dose of 60 mg and no more than three missed doses or any missed dose evaluation appointments in the past 30 days. Patients also needed to speak English and be willing to attend intervention sessions when offered. They were excluded if they were unwilling or unable to remain in MOUD treatment for the one-year trial, if they were not on medication to treat psychosis, or reported cognitive impairment due to head injury or other reasons.

Measures

Demographic characteristics, chronic pain status and substance use history

Demographic characteristics, including self-identified gender, along with other information specific to health history, was collected by patient self-report. Substance use was assessed using the Timeline Follow-Back Interview (TLFB) [45]; a calendar method used to identify substance use over the 90 days prior to study enrollment. The presence of Chronic pain was determined by a survey question: “Are you currently experiencing any bodily pain that has been present for 3 months or more?”.

Trauma history

The Trauma Life Events Questionnaire (TLEQ) was used to assess the prevalence and number of traumatic events across the lifespan [46]. The TLEQ is a 23-item self-report measure to assess lifetime exposure to a broad range of potentially traumatic events. Two sex-specific items were removed and not administered to participants: one specific to miscarriage and one specific to abortion. Participants are asked to report the number of times they experienced each event (event frequency) on a 7-point scale ranging from never to more than 5 times.

Based on the responses to the 21-item TLEQ, we chose to categorize the items by constructs identified in the literature – i.e., adult interpersonal trauma, adult non-interpersonal trauma, or childhood trauma [9]. We then examined the type of event to determine if any could be combined conceptually to minimize the number of total categories for analysis (for example, we combined natural disasters with other types of accidents to create a non-interpersonal category titled “accident”). We excluded 6 items from the original measure for which the response rate was relatively low; these were items 4 (military trauma), 6 (the survival of someone you loved after a life-threatening accident or illness), 7 (having had a life-threatening illness), 11 (witnessing a stranger beat, attack or kill someone), 19 (subjected to uninvited or unwanted sexual attention other than sexual contact covered by items 15, 16, 17, or 18), and 21 (experienced other events that were highly distressing such as lost in the wilderness; a serious animal bite; violent death of a pet; being kidnapped or held hostage; seeing a mutilated body or body parts). Our final set of 15 items and 11 categorizations are listed in Table 1.

PTSD Symptom severity

The Posttraumatic Stress Disorder Checklist for DSM 5 (PCL-5) assesses PTSD symptom severity [47]. Participants were asked to indicate how much they have been bothered by each PTSD symptom in the past month. It includes 20 items with a 5-point scale ranging from 0 (not at all) to 4 (extremely). We used a screening cut-off of > 31, indicative of probable PTSD [48]. The reliability of the PCL-5 in this sample was 0.93.

Analyses

Descriptive statistics (counts, percentages, mean values, and SDs) were used to summarize sample demographics, self-report indices, and survey scales. Independent sample t-tests were used to examine differences in trauma exposure between men and women and between those with and without chronic pain. Linear regression was used to examine whether the number of trauma events predicted PTSD symptoms. Logistic regression was used to examine whether the number of trauma events predicted PTSD status (scoring above the screening cut-point for PTSD). We examined potential covariates of sex, age, education, and time in treatment prior to study enrollment; none were significant and so were not included in the regression analyses. All analyses were conducted using Stata version 18.0 (College Station, TX, USA).

Results

Participants

This sample (N = 303) had a median age of 40, with ages ranging from 21–73. Self-reported gender in the sample was 144 male, 157 female, and two non-binary. The majority (79%) of the sample identified as White, 9% as mixed-race, 5% as Black, 4% as Native American, 1% as Asian, and 1% as Native Hawaiian or Pacific Islander. Nine percent identified as Hispanic. The highest level of education was high school for 66% of the sample. Socioeconomic status was low, reflected in the overall low employment rate (34% employed (at either full or half-time) and high public insurance rate (72%) on Medicaid. Before study enrollment, most participants (67%) were engaged in MOUD treatment for over 12 months and reported high levels of abstinence from opioids and other substances. Mental health distress was high, and chronic pain was reported in 57% of the sample [49]. Nonetheless, the majority (53%) reported no mental health services in the past 90 days, and similar numbers reported minimal engagement in lifetime mental health services (see Table 2).

Lifetime trauma exposure

All participants in the sample, with one exception (n = 302), reported at least one lifetime traumatic event. Over 70% of the sample reported exposure to five types of traumatic events. Within the category of adult interpersonal trauma: 71% reported physical assault (e.g., robbed or witnessing a robbery when a weapon was used or physically assaulted by a stranger), 79% reported intimate partner violence (IPV), and 89% reported the experience of a sudden and unexpected death of a close friend or loved one. Within the category of adult non-interpersonal trauma: 86% reported an accident (e.g., a natural disaster or injurious accident. Within the category of childhood trauma: 89% reported at least one type of traumatic event (see Table 3).

Trauma exposure and gender

Women reported significantly more trauma than men in many categories (IPV, sexual assault, being stalked, total childhood violence, childhood witness of IPV, childhood sexual abuse, and sudden death of a loved one). Men reported significantly more trauma than women in witnessing a traumatic event, physical assault, and childhood physical abuse. Notably, despite gender differences the prevalence of exposure to some of these events was very high for both men and women; for example, IPV (men 73%; women 85%), physical assault (women 61%; men 81%), total childhood violence (men 72%; women 89%), and sudden death of a loved one (men 83%; women 94%). There was equivalent exposure to accidents across genders (see Table 3).

Trauma exposure and PTSD status

In this study sample, 41% (n = 124) met the screening criteria for PTSD. Exposure to trauma was significantly higher across all categories of trauma for those positive for PTSD compared to those without, with the exception of childhood witnessing of IPV, accidents, or sudden death of a loved one (see Table 4). Notably, those with subthreshold symptoms of PTSD still reported exposure to a great deal of trauma; for example, 72% experienced IPV, 77% experienced childhood violence, and 64% reported physical assault.

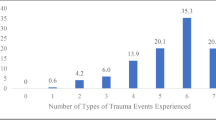

Number of trauma exposure events and PTSD symptoms and status

The number of reported traumatic events (i.e., the total number of events reported within each trauma category) predicted PTSD symptoms. Results from the univariate linear regression model showed that for every 1-point increase in the number of trauma events, there was an increase of 6.5 on the PTSD symptom scale (β = 6.5, 95% CI, 4.8–8.2; Fig. 1). Likewise, the number of traumatic events predicted PTSD status (scoring above the PTSD screening cut-off on the PCL-5; OR = 2.1; 95% CI, 1.6–27.7; Fig. 2).

Trauma exposure and chronic pain

Individuals with chronic pain, compared to those without chronic pain, reported significantly more trauma in the following categories: accidents (n = 155, 91%), childhood violence (total; n = 147, 85%), childhood physical abuse (n = 82, 48%), witnessing IPV in childhood (n = 144, 78%), childhood sexual abuse (n = 106, 62%: Table 5).

Discussion

This is the first study to examine lifetime trauma experiences among a large sample of individuals in MOUD. The results highlight the high prevalence of trauma in both childhood and in adulthood, as well as both interpersonal and non-interpersonal traumatic events in both men and women. While differences across gender and chronic pain status are notable, there was remarkably high prevalence of exposure to all trauma categories across both men and women and those with and without chronic pain, pointing to the critical need for both trauma assessment and mental health services that are accessible and integrated into MOUD treatment. Individuals in this sample were stabilized on MOUD for a substantial amount of time and reported high levels of abstinence from substance use yet were not accessing a level of mental health care commensurate with their need. Also notable is the particularly high report of sudden and unexpected death of a close friend or loved one – reflecting the tragic experience of loss among this sample likely due to drug overdose in their communities and the need for related support services.

There were distinct gender differences in trauma exposure, the most striking being the higher number of women who reported sexual abuse in childhood and sexual assault in adulthood compared to men. This finding aligns with prior research and the identified need for women-specific programs in SUD treatment to address the high prevalence of sexual trauma [13, 14]. Perhaps unexpected, although similar to study findings examining interpersonal trauma in the past 12 months among those in MOUD [17], was the high number of men who reported being victims of intimate partner violence (IPV); while not as high as the report of IPV among women, this finding warrants further research and clinical attention as it points to the need for more assessment and clinical support for IPV, for everyone regardless of gender/sex. Overall, these results point to the need to ensure that support services and trauma treatment are available and integrated into treatment to optimize outcomes for those receiving MOUD.

In this study, 41% of participants screened positive for PTSD, congruent with previously published literature [50, 51]. Given the high prevalence of many types of traumatic experiences among the participants in this sample, we could not link PTSD diagnostic status to particular types of traumatic events (i.e., whether they occurred during childhood or as an adult, whether interpersonal or non-interpersonal). However, the results demonstrate the link between the number of traumatic events experienced and PTSD symptomatology and diagnosis. These findings align with previous studies [52], including the understanding that sub-threshold PTSD symptoms are important to address and that traumatic events in both childhood or adulthood can impact symptom severity, expression, and complexity [53].

The high prevalence of chronic pain in MOUD populations allowed us to examine the relationship between trauma exposure and chronic pain. Congruent with previous studies among individuals with and without SUD, our study found that individuals with OUD and chronic pain were more likely to report traumatic accidents (e.g., car accidents, falls, natural disasters) [32,33,34,35, 37, 38, 40,41,42, 54]. Impaired cortisol secretion and psychological stress in response to a traumatic injury/ accident have been associated with the development of chronic pain over time [32]. Prior life circumstances that result in sustained, long-term cortisol surges or activations are known to contribute to cortisol dysfunction and may then increase the risk of developing chronic pain [55]. The relationship between abnormal physiological stress reactivity (i.e., heart rate, blood pressure, respiration rate, cortisol secretion) on negative health outcomes is well-established [56] and linked to pain somatization disorders [57, 58].

We also found that individuals who endorsed chronic pain were more likely to report childhood violence, including physical abuse, sexual abuse, and witnessing IPV in childhood. Most prior studies that have examined chronic pain, OUD, and childhood trauma exposure have been limited to single types of childhood abuse or neglect [38, 41]. Our findings align with prior research showing a link between childhood trauma and chronic pain in community and SUD samples, highlighting the importance of assessing PTSD symptoms among those with chronic pain in MOUD and the potential need for psychological treatment in the context of recovery.

Providing trauma-focused therapy alongside treatment for opioid use disorder [50, 58], may prove to be beneficial. Research and clinical reports describe the indirect and successful treatment of intractable and chronic pain in patients with comorbid PTSD, only after instituting behavioral therapy targeting the PTSD symptoms [60,61,62]. Cognitive-behavioral therapies with proven efficacy for the treatment of PTSD are now available to pain practitioners, and it is noteworthy that these interventions are now being tailored within comprehensive pain rehabilitation programs. Incorporating novel mindfulness and body therapy approaches to increase sensory and emotional awareness may also benefit individuals with elevated trauma symptoms and/or PTSD and co-occurring OUD, and further research is needed in this area.

There are important related clinical implications of these findings for medical providers. Given the high prevalence of trauma exposure and PTSD among individuals with OUD, evidence-based PTSD screenings, assessments, and treatments should be provided alongside MOUD [63]. Although calls to lower barriers and increase access to MOUD treatment have resulted in more primary care providers treating people with OUD [64,65,66,67] and national guidelines recommend that primary care clinics screen for depression [68] and anxiety [69], there is not a similar recommendation for universal PTSD screening [70] and, thus, the detection rate of trauma symptoms is low [71, 72].

Study limitations include the characteristics of the sample: the majority were white, low SES, and from one region of the United States, limiting generalizability. Also, only two individuals in this study identified as non-binary, limiting our ability to learn more about this population and highlighting an important line of future research. That said, while racial discrimination can increase the risk of exposure to potentially traumatic events and may influence response to traumatic events, studies have not found a difference in lifetime trauma exposure due to race among those with a substance use disorder [73,74,75]. Also, while the majority of this sample were not receiving mental health services there were participants who were; future research examining access to care and impact of services on mental and physical health symptoms among those with trauma histories is needed. This study’s strengths speak to the ways in which the findings are likely generalizable in that it includes participants from urban and rural areas and multiple practice settings. Patients reported a high proportion of days abstinent, and the majority had been in MOUD treatment for over a year, reducing the possibility that mental health symptoms were primarily substance-induced. Also, the equal number of males and females in this sample provided a unique look at the similarities as well as differences in lifetime trauma exposure among those engaged in medication treatment for OUD.

The TLEQ, the questionnaire we used to collect trauma exposure data, is comprehensive and has been used in prior research; however, until there is a more standard measure used consistently across studies, it will continue to be challenging to compare findings from one study to another in order to gather a more subtle understanding of the sequelae of trauma exposure across the lifespan [9].

In conclusion, the findings highlight the complex connection between trauma exposure, OUD, gender, PTSD symptoms, and chronic pain. This study provides valuable insights into the prevalence of trauma across genders and points to the potential impact on individuals engaged in MOUD. These findings may inform the need for enhanced screening, mental health services and approaches, and gender-specific interventions for patients engaged in MOUD treatment, potentially addressing the interconnectedness of trauma, chronic pain, and psychological distress in this population that are critical for recovery.

Availability of data and materials

The datasets generated and/or analyzed during the current study are available in the Dryad Data Repository (https://doi.org/10.5061/dryad.76hdr7t37).

Abbreviations

- SUD:

-

Substance use disorder

- PTSD:

-

Post-traumatic stress disorder

- OUD:

-

Opioid use disorder

- MOUD:

-

Medication for opioid use disorder

- TLFB:

-

Timeline follow-back interview

- TLEQ:

-

Trauma life events questionnaire

- PCL-5:

-

Posttraumatic stress disorder checklist for DSM 5

- BPI:

-

Brief pain inventory

- IPV:

-

Intimate partner violence

References

Chandler GE, Kalmakis KA, Murtha T. Screening Adults With Substance Use Disorder for Adverse Childhood Experiences. J Addict Nurs. 2018;29(3):172–8.

Pirard S, Sharon E, Kang SK, Angarita GA, Gastfriend DR. Prevalence of physical and sexual abuse among substance abuse patients and impact on treatment outcomes. Drug Alcohol Depend. 2005;78(1):57–64.

Ouimette P, Read JP, editors. Trauma and substance abuse: Causes, consequences, and treatment of comorbid disorders. 2nd ed. American Psychological Association; 2014. https://doi.org/10.1037/14273-000.

Blanco C, Wiley TRA, Lloyd JJ, Lopez MF, Volkow ND. America’s opioid crisis: the need for an integrated public health approach. Transl Psychiatry. 2020;28(10):167.

Sordo L, Barrio G, Bravo MJ, Indave BI, Degenhardt L, Wiessing L, et al. Mortality risk during and after opioid substitution treatment: systematic review and meta-analysis of cohort studies. BMJ. 2017;26(357): j1550.

Garami J, Valikhani A, Parkes D, Haber P, Mahlberg J, Misiak B, et al. Examining Perceived Stress, Childhood Trauma and Interpersonal Trauma in Individuals With Drug Addiction. Psychol Rep. 2019;122(2):433–50.

Adams RS, Dams-O’Connor K, Corrigan JD. Opioid Use among Individuals with Traumatic Brain Injury: A Perfect Storm. J Neurotrauma. 2020;37(1):211.

Lawson KM, Back SE, Hartwell KJ, Maria MMS, Brady KT. A Comparison of Trauma Profiles among Individuals with Prescription Opioid, Nicotine or Cocaine Dependence. Am J Addict Am Acad Psychiatr Alcohol Addict. 2013;22(2):127–31.

Belfrage A, Mjølhus Njå AL, Lunde S, Årstad J, Fodstad EC, Lid TG, et al. Traumatic experiences and PTSD symptoms in substance use disorder: A comparison of recovered versus current users. Nord Stud Alcohol Drugs. 2023;40(1):61–75.

Forbes D, Lockwood E, Phelps A, Wade D, Creamer M, Bryant RA, et al. Trauma at the Hands of Another: Distinguishing PTSD Patterns Following Intimate and Nonintimate Interpersonal and Noninterpersonal Trauma in a Nationally Representative Sample. J Clin Psychiatry. 2013;74(2):21205.

Scott ST. Multiple Traumatic Experiences and the Development of Posttraumatic Stress Disorder. J Interpers Violence. 2007;22(7):932–8.

Brady KT, Back SE. Childhood Trauma, Posttraumatic Stress Disorder, and Alcohol Dependence. Alcohol Res Curr Rev. 2012;34(4):408–13.

Halpern SC, Schuch FB, Scherer JN, Sordi AO, Pachado M, Dalbosco C, et al. Child Maltreatment and Illicit Substance Abuse: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis of Longitudinal Studies. Child Abuse Rev. 2018;27(5):344–60.

Covington SS. Women and Addiction: A Trauma-Informed Approach. J Psychoactive Drugs. 2008;40(sup5):377–85.

Santo TJr, Campbell G, Gisev N, Tran LT, Colledge S, Di Tanna GL, et al. Prevalence of childhood maltreatment among people with opioid use disorder: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Drug Alcohol Depend. 2021 Feb 1;219. Available from: https://libproxy.unm.edu/login?url=https://search.ebscohost.com/login.aspx?direct=true&db=psyh&AN=2021-12817-001&site=ehost-live&scope=site. Cited 2022 Feb 4.

Driscoll Powers L, Cook PF, Weber M, Techau A, Sorrell T. Comorbidity of Lifetime History of Abuse and Trauma With Opioid Use Disorder: Implications for Nursing Assessment and Care. J Am Psychiatr Nurses Assoc. 2022;10:10783903221083260.

Martin CE, Parlier-Ahmad AB, Beck L, Thomson ND. Interpersonal Trauma Among Women and Men Receiving Buprenorphine in Outpatient Treatment for Opioid Use Disorder. Violence Women. 2022;28(10):2448–65.

Hser YI, Mooney LJ, Saxon AJ, Miotto K, Bell DS, Huang D. Chronic Pain among Patients with Opioid Use Disorder: Results from Electronic Health Records Data. J Subst Abuse Treat. 2017;77:26–30.

John WS, Wu LT. Chronic non-cancer pain among adults with substance use disorders: prevalence, characteristics, and association with opioid overdose and healthcare utilization. Drug Alcohol Depend. 2020;1(209): 107902.

Barry DT, Beitel M, Cutter CJ, Garnet B, Joshi D, Rosenblum A, et al. Exploring relations among traumatic, posttraumatic, and physical pain experiences in methadone-maintained patients. J Pain Off J Am Pain Soc. 2011;12(1):22–8.

Bilevicius E, Sommer JL, Asmundson GJG, El-Gabalawy R. Posttraumatic stress disorder and chronic pain are associated with opioid use disorder: Results from a 2012–2013 American nationally representative survey. Drug Alcohol Depend. 2018;1(188):119–25.

Weiss RD, Potter JS, Fiellin DA, Byrne M, Connery HS, Dickinson W, et al. Adjunctive Counseling During Brief and Extended Buprenorphine-Naloxone Treatment for Prescription Opioid Dependence. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 2011;68(12):1238–46.

Fox AD, Sohler NL, Starrels JL, Ning Y, Giovanniello A, Cunningham CO. Pain is not associated with worse office-based buprenorphine treatment outcomes. Subst Abuse Off Publ Assoc Med Educ Res Subst Abuse. 2012;33(4):361–5.

Worley MJ, Heinzerling KG, Shoptaw S, Ling W. Pain Volatility and Prescription Opioid Addiction Treatment Outcomes in Patients with Chronic Pain. Exp Clin Psychopharmacol. 2015;23(6):428–35.

Messina BG, Worley MJ. Effects of Craving on Opioid Use Are Attenuated After Pain Coping Counseling in Adults With Chronic Pain and Prescription Opioid Addiction. J Consult Clin Psychol. 2019;87(10):918–26.

Harris IA, Young JM, Rae H, Jalaludin BB, Solomon MJ. Factors Associated With Back Pain After Physical Injury: A Survey of Consecutive Major Trauma Patients. Spine. 2007;32(14):1561.

Afari N, Ahumada SM, Wright LJ, Mostoufi S, Golnari G, Reis V, et al. Psychological Trauma and Functional Somatic Syndromes: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Psychosom Med. 2014;76(1):2–11.

Morasco BJ, Lovejoy TI, Lu M, Turk DC, Lewis L, Dobscha SK. The Relationship between PTSD and Chronic Pain: Mediating Role of Coping Strategies and Depression. Pain. 2013;154(4):609–16.

Outcalt SD, Ang DC, Wu J, Sargent C, Yu Z, Bair MJ. Pain experience of Iraq and Afghanistan Veterans with comorbid chronic pain and posttraumatic stress. J Rehabil Res Dev. 2014;51(4):559–70.

Finestone HM, Stenn P, Davies F, Stalker C, Fry R, Koumanis J. Chronic pain and health care utilization in women with a history of childhood sexual abuse11Submitted for publication November 10, 1997; final revision received July 15, 1999; accepted July 21, 1999. Child Abuse Negl. 2000;24(4):547–56.

Nicol AL, Sieberg CB, Clauw DJ, Hassett AL, Moser SE, Brummett CM. The Association Between a History of Lifetime Traumatic Events and Pain Severity, Physical Function, and Affective Distress in Patients With Chronic Pain. J Pain. 2016;17(12):1334–48.

Trevino CM, deRoon-Cassini T, Brasel K. Does opiate use in traumatically injured individuals worsen pain and psychological outcomes? J Pain. 2013;14(4):424–30.

Paras ML, Murad MH, Chen LP, Goranson EN, Sattler AL, Colbenson KM, et al. Sexual Abuse and Lifetime Diagnosis of Somatic Disorders: A Systematic Review and Meta-analysis. JAMA. 2009;302(5):550–61.

Raphael KG, Widom CS. Post-traumatic Stress Disorder Moderates the Relation Between Documented Childhood Victimization and Pain 30 Years Later. Pain. 2011;152(1):163–9.

Sansone RA, Watts DA, Wiederman MW. Childhood Trauma and Pain and Pain Catastrophizing in Adulthood: A Cross-Sectional Survey Study. Prim Care Companion CNS Disord. 2013;15(4):PCC.13m01506.

Taghian NR, McHugh RK, Griffin ML, Chase AR, Greenfield SF, Weiss RD. Associations between Childhood Abuse and Chronic Pain in Adults with Substance Use Disorders. Subst Use Misuse. 2021;56(1):87–92.

Austin AE, Shanahan ME. Association of childhood abuse and neglect with prescription opioid misuse: Examination of mediation by adolescent depressive symptoms and pain. Child Youth Serv Rev. 2018;1(86):84–93.

Boscarino JA, Rukstalis MR, Hoffman SN, Han JJ, Erlich PM, Ross S, et al. Prevalence of Prescription Opioid-Use Disorder Among Chronic Pain Patients: Comparison of the DSM-5 vs. DSM-4 Diagnostic Criteria. Diagnostic Criteria. 2011;30(3):185–94.

Groenewald CB, Law EF, Fisher E, Beals-Erickson SE, Palermo TM. Associations Between Adolescent Chronic Pain and Prescription Opioid Misuse in Adulthood. J Pain. 2019;20(1):28–37.

Prangnell A, Voon P, Shulha H, Nosova E, Shoveller J, Milloy MJ, et al. The relationship between childhood emotional abuse and chronic pain among people who inject drugs in Vancouver. Canada Child Abuse Negl. 2019;1(93):119–27.

Webster LR, Webster RM. Predicting Aberrant Behaviors in Opioid-Treated Patients: Preliminary Validation of the Opioid Risk Tool. Pain Med. 2005;6(6):432–42.

Powers A, Fani N, Pallos A, Stevens J, Ressler KJ, Bradley B. Childhood abuse and the experience of pain in adulthood: The mediating effects of PTSD and emotion dysregulation on pain levels and pain-related functional impairment. Psychosomatics. 2014;55(5):491–9.

Davis JP, Eddie D, Prindle J, Dworkin ER, Christie NC, Saba S, et al. Sex differences in factors predicting post-treatment opioid use. Addiction. 2021;116(8):2116–26.

LaBelle CT, Han SC, Bergero A, Samet JH. ffice-Based Opioid Treatment with Buprenorphine (OBOT-B): Statewide Implementation of the Massachusetts Collaborative Care Model in Community Health Centers. J Subst Abuse Treat. 2016;60:6–13.

Robinson SM, Sobell LC, Sobell MB, Leo GI. Reliability of the Timeline Followback for cocaine, cannabis, and cigarette use. Psychol Addict Behav. 2014;28(1):154–62.

Kubany ES, Leisen MB, Kaplan AS, Watson SB, Haynes SN, Owens JA, et al. Development and preliminary validation of a brief broad-spectrum measure of trauma exposure: The Traumatic Life Events Questionnaire. Psychol Assess. 2000;12(2):210–24.

Blevins CA, Weathers FW, Davis MT, Witte TK, Domino JL. The Posttraumatic Stress Disorder Checklist for DSM-5 (PCL-5): Development and Initial Psychometric Evaluation. J Trauma Stress. 2015;28(6):489–98.

Forkus SR, Raudales AM, Rafiuddin HS, Weiss NH, Messman BA, Contractor AA. The Posttraumatic Stress Disorder (PTSD) Checklist for DSM-5: A Systematic Review of Existing Psychometric Evidence. Clin Psychol Publ Div Clin Psychol Am Psychol Assoc. 2023 Mar;30(1). Available from: https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/37378352/. Cited 2023 Aug 7.

Leyde S, Price CJ, Colgan DD, Pike KC, Tsui JI, Merrill JO. Mental Health Distress Is Associated With Higher Pain Interference in Patients With Opioid Use Disorder Stabilized on Buprenorphine or Methadone. Subst Use Addict J. 2024;7:29767342241227400.

Ecker AH, Hundt N. Posttraumatic stress disorder in opioid agonist therapy: A review. Psychol Trauma Theory Res Pract Policy. 2018;10(6):636–42.

Roberts NP, Roberts PA, Jones N, Bisson JI. Psychological interventions for post-traumatic stress disorder and comorbid substance use disorder: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Clin Psychol Rev. 2015;1(38):25–38.

Kaysen D, Rosen G, Bowman M, Resick PA. Duration of Exposure and the Dose-Response Model of PTSD. J Interpers Violence. 2010;25(1):63–74.

Cloitre M, Stolbach BC, Herman JL, van der Kolk B, Pynoos R, Wang J, et al. A developmental approach to complex PTSD: Childhood and adult cumulative trauma as predictors of symptom complexity. J Trauma Stress. 2009;22(5):399–408.

Lampe A, Doering S, Rumpold G, Sölder E, Krismer M, Kantner-Rumplmair W, et al. Chronic pain syndromes and their relation to childhood abuse and stressful life events. J Psychosom Res. 2003;54(4):361–7.

Brodersen L, Lorenz R. Perceived stress, physiological stress reactivity, and exit exam performance in a prelicensure Bachelor of Science nursing program. Int J Nurs Educ Scholarsh. 2020 Jan 1;17(1). Available from: https://www.degruyter.com/document/10.1515/ijnes-2019-0121/html. Cited 2023 Nov 12.

Wrzus C, Luong G, Wagner GG, Riediger M. Longitudinal Coupling of Momentary Stress Reactivity and Trait Neuroticism: Specificity of States, Traits, and Age Period. J Pers Soc Psychol. 2021;121(3):691–706.

Ehlert U, Gaab J, Heinrichs M. Psychoneuroendocrinological contributions to the etiology of depression, posttraumatic stress disorder, and stress-related bodily disorders: the role of the hypothalamus–pituitary–adrenal axis. Biol Psychol. 2001;57(1):141–52.

Hannibal KE, Bishop MD. Chronic Stress, Cortisol Dysfunction, and Pain: A Psychoneuroendocrine Rationale for Stress Management in Pain Rehabilitation. Phys Ther. 2014;94(12):1816–25.

Fareed A, Eilender P, Haber M, Bremner J, Whitfield N, Drexler K. Comorbid posttraumatic stress disorder and opiate addiction: a literature review. J Addict Dis. 2013;32(2):168–79.

Gilliam WP, Schumann ME, Craner JR, Cunningham JL, Morrison EJ, Seibel S, et al. Examining the effectiveness of pain rehabilitation on chronic pain and post-traumatic symptoms. J Behav Med. 2020;43(6):956–67.

Bosco MA, Gallinati JL, Clark ME. Conceptualizing and Treating Comorbid Chronic Pain and PTSD. Pain Res Treat. 2013;2013: 174728.

Asmundson GJG, Taylor S. PTSD and Chronic Pain: Cognitive-Behavioral Perspectives and Practical Implications. In: Young G, Nicholson K, Kane AW, editors. Psychological Knowledge in Court: PTSD, Pain, and TBI [Internet]. Boston, MA: Springer US; 2006. p. 225–41. Available from: https://doi.org/10.1007/0-387-25610-5_13. Cited 2024 Mar 14.

Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration (US), Office of the Surgeon General (US). Facing Addiction in America: The Surgeon General’s Report on Alcohol, Drugs, and Health. Washington (DC): US Department of Health and Human Services; 2016. (Reports of the Surgeon General). Available from: http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK424857/. Cited 2023 Aug 14.

Chou R, Korthuis PT, Weimer M, Bougatsos C, Blazina I, Zakher B, et al. Medication-Assisted Treatment Models of Care for Opioid Use Disorder in Primary Care Settings [Internet]. Rockville (MD): Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality (US); 2016. (AHRQ Comparative Effectiveness Technical Briefs). Available from: http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK402352/. Cited 2023 Aug 14.

Gertner AK, Rotter JS, Holly ME, Shea CM, Green SL, Domino ME. The Role of Primary Care in the Initiation of Opioid Use Disorder Treatment in Statewide Public and Private Insurance. J Addict Med. 2022;16(2):183–91.

Saitz R, Daaleman TP. Now is the Time to Address Substance Use Disorders in Primary Care. Ann Fam Med. 2017;15(4):306–8.

Wakeman SE, Barnett ML. Primary Care and the Opioid-Overdose Crisis — Buprenorphine Myths and Realities. N Engl J Med. 2018;379(1):1–4.

US Preventive Services Task Force. Screening for Depression and Suicide Risk in Adults: US Preventive Services Task Force Recommendation Statement. JAMA. 2023;329(23):2057–67.

US Preventive Services Task Force. Screening for Anxiety Disorders in Adults: US Preventive Services Task Force Recommendation Statement. JAMA. 2023;329(24):2163–70.

Sonis J. PTSD in Primary Care—An Update on Evidence-based Management. Curr Psychiatry Rep. 2013;15(7):373.

Greene T, Neria Y, Gross R. Prevalence, Detection and Correlates of PTSD in the Primary Care Setting: A Systematic Review. J Clin Psychol Med Settings. 2016;23(2):160–80.

Murray-Krezan C, Dopp A, Tarhuni L, Carmody MD, Becker K, Anderson J, et al. Screening for opioid use disorder and co-occurring depression and post-traumatic stress disorder in primary care in New Mexico. Addict Sci Clin Pract. 2023;18(1):6.

Johnson SD, Striley C, Cottler LB. The association of substance use disorders with trauma exposure and PTSD among African American drug users. Addict Behav. 2006;31(11):2063–73.

Cottler LB, Nishith P, Compton WM. Gender differences in risk factors for trauma exposure and post-traumatic stress disorder among inner-city drug abusers in and out of treatment. Compr Psychiatry. 2001;42(2):111–7.

Dansky BS, Brady KT, Saladin ME, Killeen T, Becker S, Roitzsch J. Victimization and PTSD in Individuals with Substance Use Disorders: Gender and Racial Differences. Am J Drug Alcohol Abuse. 1996;22(1):75–93.

Acknowledgements

Not applicable.

Funding

This research was made possible by Grant Numbers R33AT009932 from the National Center for Complementary and Integrative Health (NCCIH) and R01 AT010742 from the National Center for Complementary and Integrative Health (NCCIH) and the National Institute of Neurological Disorders and Stroke (NINDS). Its contents are solely the authors' responsibility and do not necessarily represent the official views of the NCCIH, NINDS, or the National Institutes of Health.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

CJP and JOM obtained funding and oversaw data collection; CJP and MNR conceptualized the manuscript; KP was responsible for data analysis; MNR, DDC, SL, and CJP wrote the article; JOM manuscript review. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate

This study received Human Subjects Institutional Review Board approval from the University of Washington. All participants involved in this study provided consent prior to their participation. Participants were provided detailed information about the study's purpose, procedures, potential risks, benefits, and confidentiality measures. They were also informed about their right to withdraw from the study at any point without facing any consequences.

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/. The Creative Commons Public Domain Dedication waiver (http://creativecommons.org/publicdomain/zero/1.0/) applies to the data made available in this article, unless otherwise stated in a credit line to the data.

About this article

Cite this article

Rodríguez, M.N., Colgan, D.D., Leyde, S. et al. Trauma exposure across the lifespan among individuals engaged in treatment with medication for opioid use disorder: differences by gender, PTSD status, and chronic pain. Subst Abuse Treat Prev Policy 19, 25 (2024). https://doi.org/10.1186/s13011-024-00608-8

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/s13011-024-00608-8