Abstract

Background

Early initiation of breastfeeding after birth and exclusive breastfeeding for the first six months improves child survival, nutrition and health outcomes. However, only 42% of newborns worldwide are breastfed within the first hour of life. Small and sick newborns are at greater risk of not receiving breastmilk and often require additional support for feeding. This study compares breastfeeding practices in Rwandan neonatal care units (NCUs) before and after the implementation of a package of interventions aimed to improve breastfeeding.

Methods

This pre-post intervention study was conducted at two district hospital NCUs in rural Rwanda from October–December 2017 (pre-intervention) and September 2018–March 2019 (post-intervention). Only newborns admitted before their second day of life (DOL) were included. Data were extracted from patient charts for clinical and demographic characteristics, feeding, and patient outcomes. Exclusive breastfeeding at discharge was based on last recorded infant feeding on the day of discharge. Logistic regression analysis was used to evaluate factors associated with exclusive breastfeeding at discharge.

Results

Pre-intervention, 255 newborns were admitted in the NCUs and 793 were admitted in post-intervention. Exclusive breastfeeding on the day of birth (DOL0) increased from 5.4% (12/255) to 35.9% (249/793). At discharge, exclusive breastfeeding increased from 69.6% (149/214) to 87.0% (618/710). The mortality rate decreased from 16.1% (41/255) to 10.5% (83/793). Factors associated with greater odds of exclusive breastfeeding at discharge included admission during the post-intervention period (aOR 4.91; 95% CI 1.99, 12.11), and admission for infection (aOR 2.99; 95% CI 1.13, 7.93). Home deliveries (aOR 0.15; 95% CI 0.05, 0.47), preterm delivery (aOR 0.36; 95% CI 0.15, 0.87) and delayed first breastmilk feed (aOR 0.04 for DOL3 vs. DOL0; 95% CI 0.01, 0.35) reduced odds of exclusive breastfeeding at discharge.

Conclusions

Expansion and adoption of evidenced-based guidelines, using innovative approaches, aimed at the unique needs of small and sick newborns may help to improve earlier initiation of breastfeeding, decrease mortality, and improve exclusive breastfeeding on discharge from hospital among small and sick newborns. These interventions should be replicated in similar settings to determine their effectiveness.

Similar content being viewed by others

Background

Breastfeeding plays a paramount role in child survival, development and maternal health [1]. Early initiation of breastfeeding within one hour after birth and exclusive breastfeeding for the first six months is recommended by the World Health Organization (WHO) [2]. Immediate and early initiation of breastfeeding after birth is associated with better neonatal outcomes, in low- and middle-income countries (LMICs), such as reduction of neonatal deaths, length of hospital stay for sick infants and neonatal infections [3, 4]. A meta-analysis of LMIC settings, showed that non-breastfed infants under six months of age have a 14 times higher risk of death, and partially breastfed infants have a 4.8-fold higher risk of death compared to predominantly breastfed infants [5].

Even though the majority of deliveries globally are attended by skilled healthcare providers, only 42% of newborns are breastfed within the first hour of life worldwide [6]. Small and sick newborns requiring inpatient care after birth face unique challenges since the neonatal care unit environment is not always conducive for initiation of early and exclusive breastfeeding, including in settings such as Denmark, when an infant requires mechanical ventilation or is separated from the mother [7]. In addition, small and sick newborns may experience difficulties breastfeeding, or are too immature or unstable to breastfeed immediately after birth, so mothers require specialized support to establish and maintain their milk supply [8, 9]. Despite the strong recommendation from WHO that maternity and newborn services have trained and competent staff who can provide successful breastfeeding support to lactating mothers [10], they have noted that early breastfeeding is compromised by inappropriate procedures, such as infant-mother separation, performed by healthcare providers and outdated policies [6].

Many interventions exist at community and facility levels worldwide to promote early and exclusive breastfeeding. UNICEF and WHO launched the Baby-Friendly Hospital Initiative (BFHI) in 2009 to integrate breastfeeding with maternal and newborn care in hospitals. Through this multi-level approach, hospitals must implement the “Ten Steps to Successful Breastfeeding” to attain BFHI status, including having a breastfeeding policy, allowing rooming-in, and providing adequate training to staff [10, 11]. Specific recommendations for expanding BFHI to include the unique needs of small and sick newborns have also been developed [9, 12]. Additionally, utilizing lactation consultants for breastfeeding support and lactation education has shown to increase rates of initiation, duration of any breastfeeding and exclusive breastfeeding compared to usual practices in a systematic review of high-income countries [13]. Peer counseling approaches have also demonstrated improved early and continuous exclusive breastfeeding in an urban United States hospital setting [14].

In Rwanda, 81% of newborns are breastfed within one hour of life and 87% are exclusively breastfed up to six months [15], however little is known about rates among small and sick newborns. Data from a neonatal care unit (NCU) in rural Rwanda found a large proportion of small and sick newborns had breastfeeding difficulties after discharge leading to use of infant formula and poor growth [16]. To address this, Partners In Health/Inshuti Mu Buzima (PIH/IMB) in collaboration with the Ministry of Health, implemented interventions for breastfeeding support for newborns and infants with feeding difficulties in NCUs. This included training of healthcare providers, breastfeeding counselling for mothers and health system strengthening to promote early and exclusive breastfeeding. This study aims to compare breastfeeding rates of newborns admitted to district hospital neonatal special care units before and after the implementation of a package of interventions aimed to improve breastfeeding practices.

Methods

Study setting

We conducted this study in the Rwinkwavu District Hospital (RDH) and Kirehe District Hospital (KDH) NCUs. RDH and KDH are Rwandan Ministry of Health public hospitals located in Kayonza and Kirehe Districts in the eastern province of Rwanda. Both RDH and KDH have been supported by PIH/IMB, an international non-governmental organization, since 2005 and 2007, respectively. RDH supervises eight health centers in its catchment area with a population of 215,555 and KDH supervises 16 health centers in its catchment area with a population of 384,776 [17], in addition to two health centers and over 60,000 people in a refugee camp in the catchment area [18]. The NCUs provide care for small and sick newborns and are equipped with incubators, radiant warmers, syringe pumps, phototherapy, oxygen and continuous positive airway pressure machines for the management of common neonatal conditions. They are staffed by nurses, with an average nurse to patient ratio of 1 to 8.5 [19], and general practitioners, with mentorship by a pediatrician and midwife. Typically, there is one general practitioner who conducts rounds on patients on the neonatal unit each day. The education level of the nurses vary, and include, either a general nurse with a two-year diploma (A1 level) or a general nurse with a Bachelor’s degree (A0 level).

Intervention

Several inputs were introduced into the hospital neonatal care units to promote exclusive breastfeeding, including porridge for mothers and water filters to provide a high calorie, high protein supplement and ensure adequate hydration; pillows for more comfortable breastfeeding positioning; screens for mothers to breastfeed or express breastmilk privately; refrigerator and materials for storage of expressed breastmilk, and educational posters promoting exclusive breastfeeding and Kangaroo Mother Care (KMC). In addition to these inputs, a training was conducted in February 2018 called Working with Infants with Feeding Difficulties delivered by two Speech and Language Therapists who are experts in infant feeding. A description of that training package and a case study from its implementation in Rwanda has been described elsewhere [20]. As a result of the training and in an effort to ensure sustainability of the skills learned during the training, each hospital hired two Expert Mothers to serve as peer counsellors to support mothers in assessing breastfeeding readiness, improve positioning and attachment, and create a breastfeeding-friendly, caring environment for mothers with a focus on one-to-one as well as group counselling. The Expert Mothers were chosen based on criteria including previously having an infant in the neonatal unit and commitment to sharing her experience with other mothers. The Expert Mothers are trained on the Working with Infants with Feeding Difficulties package, provided with a job aid and tablet loaded with Global Health Media videos for counselling of mothers.

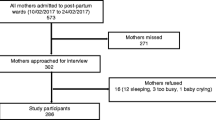

Study design and population

We conducted a pre-post study. We included all newborns admitted to the RDH and KDH neonatology units in two periods including pre-intervention from October 2017 to December 2017 and post-intervention from September 2018 to March 2019 who were admitted before their second day of life. The manuscript was prepared following the Standards for Quality Improvement Reporting Excellence (SQUIRE 2.0) Guidelines [21].

Data collection

Data from nationally standardized neonatology patient charts is routinely collected by trained data collectors on a structured paper, two-page form and then entered in a Microsoft Access database. Data completeness and accuracy were checked through routine data quality assessment activities that are conducted by monitoring and evaluation staff. Types of data collected about the infant include the infant’s reason for admission, day of life on admission, relevant perinatal history, length of stay, and discharge outcomes. Data collected about the mother includes maternal history, such as age, gravida, and para, and type of delivery. A very detailed feeding and weight gain history is recorded on the paper form, including the nutrition method through which the infant was receiving nutritional support (via the breast, via a naso-gastric tube, via a cup, or nil per os [NPO, nothing by mouth].) and the nutrition type (breastmilk only, breastmilk and artificial milk, artificial milk only, or intravenous fluids).

Definition of variables

Our primary outcome was exclusive intake of breast milk at the time of discharge among infants discharged alive. Data on the infant’s feeding history which was last recorded in the patient chart on the day of discharge was used to assess exclusive breastfeeding at the time of discharge. Day of life 0 (DOL0) referred to the child’s day of birth. Newborns exclusively fed breastmilk were defined as the feeding type recorded in the patient’s chart as ‘only breast milk’, regardless of the method of feeding (i.e., via breast, via naso-gastric tube, etc.). Fed on breast was defined as the method of feeding recorded in the patient’s chart as ‘only on the mother’s breast’ (i.e., not via cup, not via naso-gastric tube, etc.). Low birthweight (LBW) was defined as any birth below 2,500 g and premature births are births before 37 weeks gestation. Home delivery was defined as a birth that takes place in the community outside of the care of a skilled healthcare provider, regardless of whether the home delivery was planned delivery or a precipitous delivery.

Data analysis

We described sociodemographic characteristics of infants and their mothers, and clinical and feeding characteristics of infants using frequencies and percentages for categorical data and median and interquartile ranges for continuous data. We conducted bivariate analysis using Chi-square test to compare the pre- and post-intervention periods for all categorical sociodemographic, clinical and feeding characteristics described for infants with data recorded unless a cell contained a value of less than five, in which case Fisher’s exact test was used. Wilcoxon Ranksum test was used for bivariate analysis of continuous variables for infants with data recorded. We assessed change in mortality from pre- to post-intervention using multivariable logistic regression controlling for the child’s condition, birthweight in grams, and child’s sex. Then, we used multivariable logistic regression models to identify predictors associated with the outcome ‘exclusive breastfeeding on discharge’, built using backward stepwise procedures for all variables significant at α = 0.20 in bivariate analyses. All factors significant at the α = 0.05 significance level were retained in the final model. The data were analyzed using Stata v.15.1 (Stata Corp, College Station, TX, USA).

Ethics

The study received ethical approval from the Rwanda National Ethics Committee (No. 105/RNEC/20). Data was captured through review of routine records and so additional informed consent specific to this study was not required.

Results

In total, 255 newborns were admitted in the neonatology care units during the pre-intervention and 793 were admitted in the post-intervention periods (Table 1). There were no significant differences in admissions for prematurity at pre-intervention compared to post-intervention (40.0% [n = 96/240] vs. 40.6% [n = 309/762], p = 0.88), maternal age (50.0% [n = 12/240] age 25–34 years vs. 43.7% [n = 332/759], p = 0.24) maternal gravidity (27.1% [n = 66/244] primigravida vs 31.5% [n = 238/755], p = 0.40), and age on admission (83.1% [n = 212/255] admitted on DOL0 vs. 85.4% [n = 677/793, p = 0.39). Compared to the pre-intervention period, infants were also more likely than in the post-intervention period to be delivered by caesarean section (31.5% [n = 79/251] vs. 41.1% [n = 315/767], p = 0.01) and weigh more than 1,500 grams (86.6% [n = 220/254] vs. 91.9% [n = 722/786], p = 0.02).

The percentage of infants who were fed on the breast on DOL0 increased from 5.8% (n = 13/223) to 35.6% (n = 247/694), (p < 0.001) and exclusively breastfed on DOL0 increased from 5.4% (n = 12/255) to 35.9% (n = 249/793) (p < 0.001) (Table 2). On DOL1, feeding on the breast increased from 30.5% (n = 75/246) to 68.6% (n = 532/776) (p < 0.001) and exclusive feeding on breastmilk increased from 37.4% (n = 92/255) to 70.2% (n = 545/793) (p < 0.001). For newborns discharged alive, the proportion fed on the breast increased from 59.8% (n = 128/255) to 84.7% (n = 601/793) (p < 0.001) and the proportion exclusively feeding on breastmilk increased from 69.6% (n = 149/255) to 87.0% (n = 618/793) (p < 0.001). Introduction of first breast milk feeding on DOL0 increased from 7.1% (n = 18/255) pre-intervention to 31.9% (n = 253/793) in post-intervention (p < 0.001).

The median length of hospital stay among infants admitted to the neonatal unit was reduced from eight days in the pre- to seven days in the post-intervention periods (p < 0.001) (Tables 3 and 4). The overall mortality rate for all newborns admitted decreased from 16.1% (n = 41/255) in pre- to 10.5% (n = 83/793) in post-intervention periods (p = 0.02). Mortality rate for LBW newborns reduced from the pre-intervention to post-intervention period (23.6% [n = 29/255] vs. 15.0% [n = 61/793], p = 0.03), but remained similar among babies diagnosed with other conditions. Reduced odds of mortality post-intervention were significant when controlling for diagnosis, birthweight, and child’s sex (adjusted odds ratio [aOR] 0.57; 95% confidence interval [CI] 0.34, 0.96).

In the final model (Table 5), there was a significant increase in exclusive feeding of breastmilk at discharge if admitted in the post-intervention period (aOR 4.91; 95% CI 1.99, 12.11). Factors associated with increased odds of exclusive breastfeeding at discharge included diagnosis of infection or infection risk (aOR 2.99; 95% CI 1.13, 7.93). Factors associated with reduced odds of exclusive breastfeeding at discharge included home birth (aOR 0.15; 95% CI 0.05, 0.47), prematurity (aOR 0.36; 95% CI 0.15, 0.87), and later timing of first breastmilk feed (DOL2 aOR 0.11; 95% CI 0.01, 0.995; DOL3 or later aOR 0.04; 95% CI 0.005, 0.35).

Discussion

Our study showed that a multi-level intervention, aimed at improving rates of exclusive breastfeeding on a hospital neonatology unit in rural Rwanda, increased early and exclusive breastmilk feeding, and was also associated with a reduced length of stay and decreased mortality among small and sick newborns. These strategies have potential for expansion to other similar contexts, and may improve hospital neonatal outcomes and ensure small and sick newborns will benefit from the well-known long-term benefits of breastfeeding [1].

We found that from the pre- to post-intervention period, significantly more infants were fed on the breast and were exclusively fed breastmilk. We also observed earlier initiation of breastfeeding in the post-intervention and this earlier initiation increased the odds that an infant was discharged exclusively feeding on breastmilk. This is consistent with other literature as it is well known that if milk removal does not occur either by infant suckling or expression by hand or pump, milk secretion will start to decline around day three postpartum [22, 23]. A study from the United States comparing milk expression within one hour after delivery to within 1–6 h after delivery showed that the earlier expression group had earlier lactogenesis stage II (transition from colostrum to copious breast milk production) and resulted in higher milk volume [24]. Another study from the United States showed that milk volume on postpartum day four is predictive of having an adequate milk supply at six weeks [25]. These studies demonstrate the critical need for early expression of breast milk after delivery, whether the infant is able to breastfeed on the breast or if the mother expresses breastmilk and the infant receives breastmilk through other enteral feeding routes (i.e., cup, nasogastric tube).

Mortality among newborns decreased from the pre- to post-intervention period, particularly among infants born with a low birthweight. The association between decreased mortality and exclusive breastfeeding among infants in all settings has been well established in the literature and is often promoted as strong support for initiation of early and exclusive breastfeeding [1, 3,4,5,6, 26].

Overall length of hospital stay showed a significant reduction from the pre- to post-intervention period. While hospital neonatology units are meant to be an environment for infants to improve from various illnesses or conditions, a study from a United States hospital has shown that long length of stay in hospitals also increases an infant’s chance of contracting hospital acquired infections [27]. Therefore, the ability to reduce the length of stay for newborns may have an impact on the overall morbidity of the infant. While we did not measure morbidity in this study, early initiation of breastfeeding has been shown to reduce morbidity in newborns in LMIC settings [3], which likely has a positive impact on the total length of hospitalization. Studies from the United States and New Zealand have shown that reducing the time families, particularly mothers, spend in hospitals can also have a significant impact on the mother’s stress, and the family’s economic situation [28, 29]. Reduced length of stay was likely a secondary outcome of improved breastfeeding rates in the post-intervention period. The overall larger number of admissions with a birthweight greater than 1,500 g and gestational age over 32 weeks in the post-intervention period may have also contributed to lower mortality and shorter length of stay.

We found that the location of where the infant is born was associated with whether they are discharged from the hospital with exclusive breastfeeding or not. Infants born at health centers or in the home (including both planned home deliveries and precipitous deliveries) were less likely to be discharged with exclusive breastfeeding, compared to those born in the hospital which has also been seen in other studies of sub-Saharan Africa and LMIC settings [30, 31]. There may be many reasons for this. Infants born at home need to first be transferred to the health center, and subsequently to the hospital which may delay the introduction of breastmilk for those infants, and subsequently impact whether the infant is discharged exclusively breastfeeding. The clinical staff at health centers may also be less experienced in caring for high-risk newborns, and may not follow essential newborn care practices and delay introduction of breastmilk since the infant needs to be clinically stabilized and then transferred to the hospital.

Infants born preterm were less likely to be discharged exclusively breastfeeding compared to infants born at term. Infants born preterm have unique feeding needs that require specialized interventions and management, and a study from Australia has demonstrated similar findings of reduced exclusive breastfeeding rates even among moderate to late preterm newborns compared to term newborns [32]. Similarly, infants admitted for infection risk or neonatal infection in our study had much higher odds of exclusive breastfeeding. These findings are not surprising, as these infants are often term and feed easily. But notably, even when considering all of these factors in multivariate analysis the admission during the post-intervention period was the strongest predictor of exclusive breastfeeding at the time of discharge with nearly double the odds of exclusive breastfeeding compared to the pre-intervention period. Other factors in the neonatal care unit environment may also interfere with early and exclusive breastfeeding, including delayed initiation of KMC, or skin-to-skin contact, especially for sick newborns as seen in high- and middle-income country setting [33]. We were unable to measure timing or duration of KMC but this is an area that warrants further attention to reduce breastfeeding barriers.

Our study has some limitations. First, we used routinely collected data for the study, which results in some missing data and reliance on clinician skills in completion of medical files. In addition, precise measurement of gestational age is a challenge in Rwanda like in other low- and middle-income countries where availability of ultrasound dating is limited. Due to the use of routine data, it was not possible to reliably discriminate between newborns with infection or those with risk of infection and so we included all of these newborns in our sample. We also had a small sample size of patients born with HIE and those born with extremely low birthweight, which prevented measurement of the impact of interventions on these subsets. In addition, our pre-post design without a comparison group in only two hospitals does not allow us to determine effectiveness of the intervention as changes over time could be influenced by other factors and may not be generalizable to other hospitals. Another potential limitation of this study is that the two study periods, pre-intervention from October 2017 to December 2017 and post-intervention from September 2018 to March 2019, were not exactly aligned which may have led to differences in characteristics among the study populations, including the nutritional status of the mother in both the prenatal and postpartum periods. We also had a small proportion of cases of home births (6.3% in the pre-intervention and 8.9% in the post-intervention group). While most deliveries in Rwanda take place in a health facility (greater than 90%) [15], we do not know whether the home births in our study were planned deliveries or precipitous deliveries, which may also have implications for the prenatal care that was received, as well as other factors.

Conclusions

A multi-level breastfeeding intervention was feasible to implement in rural Rwandan hospitals and was associated with improvements in earlier initiation of breastmilk feeding, exclusive breastfeeding on discharge, reduced length of stay, and decreased mortality among infants admitted to the hospital neonatal care units. Adoption of evidenced-based guidelines such as the Baby Friendly Hospital Initiative aimed at the unique needs of small and sick newborns and innovative interventions should be expanded and adapted in similar settings to improve outcomes for these infants.

Availability of data and materials

The datasets used and/or analyzed during the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

Abbreviations

- BFHI:

-

Baby-Friendly Hospital Initiative

- DOL:

-

Day of life

- HIE:

-

Hypoxic ischemic encephalopathy

- LBW:

-

Low birth weight

- LMIC:

-

Low- and middle-income countries

- KMC:

-

Kangaroo Mother Care

- KDH:

-

Kirehe District Hospital

- NCU:

-

Neonatal Care Unit

- PIH/IMB:

-

Partners In Health/Inshuti Mu Buzima

- RDH:

-

Rwinkwavu District Hospital

References

Victora CG, Bahl R, Barros AJ, França GVA, Horton S, Krasevec J, et al. Breastfeeding in the 21st century: epidemiology, mechanisms, and lifelong effect. Lancet. 2016;387(10017):475–90. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0140-6736(15)01024-7.

WHO. Exclusive breastfeeding for six months best for babies everywhere. World Health Organization. 2011. https://www.who.int/mediacentre/news/statements/2011/breastfeeding_20110115/en/. Accessed 20 February 2020.

Debes AK, Kohil A, Walker N, Edmond K, Mullany LC. Time to initiation of breastfeeding and neonatal mortality and morbidity: a systematic review. BMC Public Health. 2013;13(3):S19. https://doi.org/10.1186/1471-2458-13-S3-S19.

Smith ER, Hurt L, Chowdhury R, Sinha B, Fawzi W, Edmond KM, et al. Delayed breastfeeding initiation and infant survival: A systematic review and meta-analysis. PLoS ONE. 2017;12(7): e0180722. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0180722.

Sankar MJ, Sinha B, Chowdhury R, Bhandari N, Taneja S, Martines J, et al. Optimal breastfeeding practices and infant and child mortality: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Acta Paediatr. 2015;104(467):3–13. https://doi.org/10.1111/apa.13147.

UNICEF, WHO. Capture the moment – early initiation of breastfeeding: the best start for every newborn. New York: UNICEF; 2018.

Maastrup R, Hansen BM, Kronborg H, Bojesen SN, Hallum K, Frandsen A, et al. Breastfeeding progression in preterm infants is influenced by factors in infants, mothers and clinical practice: the results of a national cohort study with high breastfeeding initiation rates. PLoS ONE. 2014;9(9): e108208. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0108208.

Lavallée A, De Clifford-Faugère G, Garcia C, Fernandez Oviedo AN, Héon M, Aita M. Part 1: Narrative overview of developmental care interventions for the preterm newborn. J Neonatal Nurs. 2019;25(1):3–8. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jnn.2018.08.008.

Nyqvist KH, Häggkvist AP, Hansen MN, Kylverg E, Frandsen AL, Maastrup R. Expansion of the baby-friendly hospital initiative ten steps to successful breastfeeding into neonatal intensive care: expert group recommendations. J Hum Lact. 2013;29(3):300–9. https://doi.org/10.1177/0890334413489775.

WHO. Implementation guidance: protecting, promoting and supporting breastfeeding in facilities providing maternity and newborn services – the revised baby-friendly hospital initiative. Geneva: World Health Organization; 2018.

WHO. Baby-friendly hospital initiative: revised, updated and expanded for integrated care. Geneva: World Health Organization; 2009.

Spatz DL. Ten steps for promoting and protecting breastfeeding for vulnerable infants. J Perinat Neonatal Nurs. 2004;18(4):385–96. https://doi.org/10.1097/00005237-200410000-00009.

Patel S, Patel S. The effectiveness of lactation consultants and lactation counselors on breastfeeding outcomes. J Hum Lact. 2016;32(3):530–41. https://doi.org/10.1177/0890334415618668.

Meier PP, Engstrom JL, Rossman B. Breastfeeding peer counselors as direct lactation care providers in the neonatal intensive care unit. J Hum Lact. 2013;29(3):313–22. https://doi.org/10.1177/0890334413482184.

National Institute of Statistics of Rwanda (NISR) [Rwanda], Ministry of Health (MOH) [Rwanda], ICF International. Rwanda Demographic and Health Survey 2014–15. Rockville, Maryland, USA: NISR, MOH and ICF International; 2015.

Beck K, Kirk CM, Bradford J, Mutaganzwa C, Nahimana E, Bigirumwami O. The Paediatric Development Clinic: a model to improve outcomes for high-risk children aged under five in rural Rwanda. Emergency Nutrition Network Field Exchange. 2018;58:51–3.

National Institute of Statistics of Rwanda (NISR) [Rwanda], Ministry of Finance and Economic Planning (MINECOFIN) [Rwanda]. Rwanda Fourth Population and Housing Census. Thematic Report: Population Size, Structure and Distribution. Kigali: Republic of Rwanda; 2012.

United Nations High Commission for Refugees (UNHCR). Operational Update. Kigali. 2019. https://www.unhcr.org/rw/wp-content/uploads/sites/4/2019/10/August-2019-UNHCR-Rwanda-Operational-Update-002.pdf. Accessed 20 February 2020.

MCSP (Maternal and Child Survival Project). Situation analysis of inpatient care of newborns and young infants Rwanda. Kigali: MCSP; 2019.

de Silva M, Asir M, Beck K, Kirk CM, Karangwa E, Saidath G, Manirakiza L. Improving practical skills for breastfeeding vulnerable infants in low resource settings: A case study from Rwanda. Emergency Nutrition Network Field Exchange. 2019;61:7.

Ogrinc G, Davies L, Goodman D, Batalden P, Davidoff F, Stevens D. SQUIRE 2.0 (Standards for QUality Improvement Reporting Excellence): revised publication guidelines from a detailed consensus process. BMJ Qual Saf. 2016;25(12):986–92. https://doi.org/10.1136/bmjqs-2015-004411.

Wambach K, Genna KW. Anatomy and physiology of lactation. In: Breastfeeding and Human Lactation. Enhanced fifth Edition. Edited by Wambach K, Riordan J. Massachusetts, USA: Jones & Battlett Learning; 2016.

Kent JC, Prime DK, Garbin CP. Principles for maintaining or increasing breast milk production. J Obstet Gynecol Neonatal Nurs. 2012;41(1):114–21. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1552-6909.2011.01313.x.

Parker LA, Sullivan S, Krueger C, Kelechi T, Mueller M. Effect of early breast milk expression on milk volume and timing of lactogenesis stage II among mothers of very low birth weight infants: a pilot study. J Perinatol. 2012;32(3):205–9. https://doi.org/10.1038/jp.2011.78.

Hill PD, Aldag JC. Milk volume on day 4 and income predictive of lactation adequacy at 6 weeks of mothers of nonnursing preterm infants. J Perinat Neonatal Nurs. 2005;19(3):273–82. https://doi.org/10.1097/00005237-200507000-00014.

WHO. Survive and thrive: transforming care for every small and sick newborn. Geneva: World Health Organization; 2019.

Saiman L. Risk factors for hospital-acquired infections in the neonatal intensive care unit. Semin Perinatol. 2002;26(5):315–21. https://doi.org/10.1053/sper.2002.36264.

Rogers CE, Kidokoro H, Wallendorf M, Inder TE. Identifying mothers of very preterm infants at-risk for postpartum depression and anxiety before discharge. J Perinatol. 2013;33(3):171–6. https://doi.org/10.1038/jp.2012.75.

Carter J, Mulder R, Bartram A, Darlow B. Infants in a neonatal intensive care unit: parental response. Arch Dis Child Fetal Neonatal Ed. 2005;90(2):F109–13. https://doi.org/10.1136/adc.2003.031641.

Yalçin SS, Berde AS, Yalçin S. Determinants of exclusive breastfeeding in sub-Saharan Africa: a multilevel approach. Paediatr Perinat Epidemiol. 2016;30(5):439–49. https://doi.org/10.1111/ppe.12305.

Kavle JA, LaCroix E, Dau H, Engmann C. Addressing barriers to exclusive breast-feeding in low- and middle-income countries: a systematic review and programmatic implications. Public Health Nutr. 2017;20(17):3120–34. https://doi.org/10.1017/S1368980017002531.

Ayton J, Hansen E, Quinn S, Nelson M. Factors associated with initiation and exclusive breastfeeding at hospital discharge: late preterm compared to 37 week gestation mother and infant cohort. Int Breastfeed J. 2012;7:16. https://doi.org/10.1186/1746-4358-7-16.

Cartwright J, Atz T, Newman S, Mueller M, Demirci JR. Integrative review of interventions to promote breastfeeding in the late preterm infant. J Obstet Gynecol Neonatal Nurs. 2017;46(3):347–56. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jogn.2017.01.006.

Acknowledgements

We would like to acknowledge the contributions of the neonatal unit nurses and the Expert Mothers for their commitment to the care of small and sick newborns. The manuscript was developed as part of a research-capacity building training in maternal and child health research at Partners In Health/Inshuti Mu Buzima led by Alphonse Nshimyiryo, Catherine M. Kirk, and Kathryn Beck and based on the Intermediate Operational Research Training developed by Bethany Hedt-Gauthier at Harvard Medical School

Funding

This study was funded by the Primates World Relief and Development Fund and Global Affairs Canada, who provided the funding for the interventions and evaluations. MAITS provided funding for the Infants with Feeding Difficulties trainers. Primates World Relief and Development Fund,Global Affairs Canada,MAITS

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

SG, AM, and FB led the study design, literature search, data cleaning and analysis, results interpretation, and writing manuscript. HH, CMK, and KB provided input in the study design, literature search, data cleaning and analysis, results interpretation, and critically reviewed the writing manuscript. CPDS, MA, HDS, AN, MLM, EK, and TA contributed to the interpretation of results and review of final manuscript. All authors reviewed and approved the final manuscript and had access to the data.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate

This study was approved by the Rwanda National Ethics Committee (No. 105/RNEC/20). Data was captured through review of routine records and so informed consent was not required.

Consent for publication.

Not applicable.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/. The Creative Commons Public Domain Dedication waiver (http://creativecommons.org/publicdomain/zero/1.0/) applies to the data made available in this article, unless otherwise stated in a credit line to the data.

About this article

Cite this article

Gato, S., Biziyaremye, F., Kirk, C.M. et al. Promotion of early and exclusive breastfeeding in neonatal care units in rural Rwanda: a pre- and post-intervention study. Int Breastfeed J 17, 12 (2022). https://doi.org/10.1186/s13006-022-00458-9

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/s13006-022-00458-9