Abstract

Background

Prenatal knowledge, attitude, and intention related to breastfeeding are postulated as important modulators of feeding practices. Using data from the Mother and Infant Nutritional Assessment (MINA) study, a three year cohort conducted in Lebanon and Qatar, this study aimed to characterize breastfeeding practices during the first six months postnatally and examine their associations with prenatal breastfeeding knowledge, attitude, exposure, and intention.

Methods

Pregnant women during their first trimester were recruited from primary healthcare centers in Beirut and Doha. Data collection was conducted in 2015 − 2018. Participants were followed-up until the child was twoyears old. Exposure, knowledge, attitude, and intentions regarding breastfeeding were assessed during the third trimester of pregnancy (n = 230), using validated questionnaires and scales. Breastfeeding practices were evaluated at four months (n = 185) and six months (n = 151) postpartum. Early initiation of breastfeeding was defined as putting the infant to the breast within one hour of birth, and exclusive breastfeeding (EBF) as feeding exclusively with breast milk.

Results

Breastfeeding practices were as follows: ever breastfeeding: 95.8%; early initiation of breastfeeding: 72.8%; breastfeeding at four and six months: 70.3% and 62.3%; EBF at four and six months: 35.7% and 18.5%. Over 95% of participants had high breastfeeding exposure, and 68.8% had strong / very strong intentions to breastfeed. Only 25% had very good knowledge, and 9.2% reported positive/strong positive attitude towards breastfeeding. After adjustment, high exposure was associated with greater odds of breastfeeding initiation (OR 10.1: 95% CI 1.25, 80.65). Both positive attitude towards breastfeeding and strong intention to breastfeed were associated with EBF at four months (OR 2.51; 95% CI 1.02, 6.16 and OR 4.0; 95% CI 1.67, 9.6), breastfeeding at four months (OR 2.92: 95% CI 1.29, 6.62 and OR 5.00: 95% CI 2.25, 11.1), and breastfeeding at six months (OR 3.74: 95% CI 1.24, 11.32 and OR 8.29: 95% CI 2.9, 23.68).

Conclusions

Findings of this study documented suboptimal knowledge and attitude towards breastfeeding and showed that prior exposure, a positive attitude, and a strong intention to breastfeed prenatally were significant predictors of breastfeeding practices postnatally. This highlights the need to develop specific interventions and policies aimed at improving breastfeeding attitudes and creating an enabling environment that supports women throughout their breastfeeding journey.

Similar content being viewed by others

Background

Adequate nutrition during the first 1000 days of life [1], has been recognized as a window of opportunity for fostering optimal health and development, while also reducing the risk of non-communicable diseases (NCDs) later in life [2, 3]. The World Health Organization (WHO) recommends breastfeeding (BF) newborns within one hour after birth, exclusive breastfeeding (EBF) for the first six months of life, and continued BF until two years of age with appropriate complementary feeding initiated at six months [4]. EBF for the first six months of life was found to promote sensory, cognitive and socio-emotional development in infants, decrease the risk of respiratory and gastro-intestinal infections, improve growth, and reduce the risk of stunting [5,6,7,8,9,10,11,12,13,14]. Despite the evidence supporting the importance of BF for child health, early life feeding practices remain suboptimal at the global level [15, 16]. To improve infant and young child nutrition, the World Health Assembly endorsed, in 2012, the WHO global nutrition targets, which include increasing the rate of EBF in the first six months up to at least 50% in 2025 (Target 5) [17].

As infant feeding decisions appear to be made prenatally [18], pregnant women represent a key population of interest for characterizing the culturally prevalent norms, knowledge, and attitude towards BF, and for identifying misconceptions and negative perceptions that may lead to inadequate BF practices [19,20,21]. Studies have shown that the determinants of BF initiation, duration, and exclusivity are multifactorial and operate at multiple levels [10, 11, 22,23,24,25,26,27,28,29]. They include demographic and socioeconomic factors such as maternal age, education, parity, monthly income, and mother’s working status [23]; community support and structural factors; sociocultural beliefs and misconceptions prevalent in the community and among healthcare practitioners [24─26], as well as personal factors such as knowledge about the benefits of BF [27]. The theory of planned behavior has been extensively used to predict BF practices in various cultural settings [30]. According to this theory, BF intention is a direct precursor to BF behavior and practices. The intention to breastfeed is in turn influenced by maternal knowledge and attitude towards BF as well as the mother’s prior exposure to BF [31, 32]. Several cross-sectional studies conducted among pregnant women have established a link between BF exposure, knowledge, and attitude, with the intention to BF prenatally [20, 23, 29, 33]. However, few studies have investigated, longitudinally, the association between these maternal prenatal attributes and actual BF practices postnatally [22, 34]. This is important given that some studies have shown that, even among women who expressed their intention to breastfeed, few were able to achieve their intended BF or EBF duration [35]. Gaining a deeper understanding of the context-specific determinants of infant feeding practices is vital for the development of more effective BF promotion programs and informing local policies [36]. This may be particularly true for the Eastern Mediterranean Region (EMR), a region where the prevalence of EBF for the first six months postnatally does not exceed 30% [9, 37], and where data on the determinants of infant feeding practices are scarce [10, 11, 23, 29, 33].

To move this agenda forward, the ‘Mother and Infant Nutritional Assessment’ (MINA) cohort, was launched in 2015, as the first mother and child cohort in the EMR. It consists of a three year follow-up study of pregnant women and their children, in two Arab countries of the EMR, Lebanon and Qatar [38, 39]. Despite having discrepant income and development indicators, the prevalence of EBF is low in both Lebanon (12.3% in 2012, based on a questionnaire administered in a face-to-face interview) and Qatar (26% in 2019, based on a questionnaire administered via phone) [40, 41]. Using data stemming from the MINA cohort, the objectives of this study are to 1) characterize BF practices among the MINA cohort participants during the first six months postnatally and identify their correlates, 2) describe prenatal BF knowledge, attitude, exposure, and intention in the study sample, and 3) examine the association of prenatal BF knowledge, attitude, exposure, and intention with BF practices during the first six months postnatally.

Methods

Study design

Data for this study were derived from the MINA cohort conducted in Lebanon and Qatar. Details about the protocol and data collection of this cohort are described elsewhere [38]. Briefly, the MINA cohort is a three year longitudinal prospective study, where pregnant women are recruited during their first trimester. After delivery, women and their children are followed-up until the child is two years of age. Recruitment of subjects took place in various primary healthcare centers in Doha and Beirut. Over the course of the MINA cohort study, data collection was carried out in nine visits.

Ethical considerations

The protocols used in the MINA cohort were reviewed and approved by two independent research ethics boards: the Institutional Review Board at the American University of Beirut (Protocol ID: NUT. FN. 12) and the Primary Health Care Corporation in Qatar (Protocol ID: PHCC / RC / 15 / 04 / 006). All MINA participants provided a written signed consent form. Subjects were reassured that their participation is completely voluntary, that they can withdraw at any time, and that their decision to continue or not in the study will not influence their provision of healthcare services.

Study population

Subjects’ recruitment and data collection were performed in 2015 − 2018. To be eligible to participate, women had to be pregnant during their first trimester, pregnant with a singleton, of Lebanese or Qatari nationality, living in Lebanon or Qatar for more than five years, not planning to leave the current country of residence during the timeframe of the study, and not suffering from any chronic condition. In order to estimate the prevalence of exclusive BF, a total of 218 participants were needed for an effect size of 29%, a margin of error of 6% and a 95% confidence interval [42]. The 29% prevalence estimate was selected as an effect size as it reflected the average EBF for six months in the countries of the EMR [9].

Study protocol and data collection

Through the MINA cohort, data collection was conducted during a one-to-one interview with the research personnel. All interviewers had received extensive training prior to the initiation of data collection in order to minimize interviewer errors. For the purpose of this study, data were extracted from visit 1 (first trimester), visit 3 (third trimester), the medical chart (at birth), visit 4 (four months after delivery), and visit 5 (six months after delivery) of the MINA cohort, as shown in Fig. 1. Below is a brief description of the data extracted from the MINA cohort and used in the study. Further details can be found at Naja et al. (2016) [38]:

- Sociodemographic characteristics (visit 1): age of the mother, number of children (excluding the current pregnancy), number of individuals living in the house, number of rooms in the house, education level, employment status, being related to husband, education level and employment status of the husband, and income. Crowding Index (CI), calculated as a ratio of the number of individuals living in the house over the number of the rooms in the house, was used as a proxy of socioeconomic status (SES) [43].

- Delivery and infant characteristics (medical charts): type of delivery, occurrence of complications during delivery, gestational age classification of the offspring, and birth weight of the offspring (in grams); classified as either low birth weight (< 2500 g), normal weight (2500 − 4000 g) or macrosomic (> 4000 g) [44].

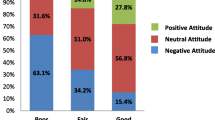

- Exposure, knowledge, attitude, and intentions regarding BF (visit 3): Information regarding exposure, knowledge, attitude, and intentions regarding BF were collected at visit 3. Prior exposure to BF was examined using the three questions proposed by Kavangh et al.: Ever been breastfed, knowing someone who has breastfed, and whether or not the participants have witnessed other women BF [31]. The answers to these questions were either yes (1 point) or no (0 points), except for ever been breastfed where a third option was given (unsure, also given 0 points). Using the total BF exposure score, participants were classified into low BF exposure (0 − 1 score) and high BF exposure (2 − 3 scores) [45]. The validated Arabic Breastfeeding Knowledge Questionnaire (BFK-A) was used to investigate the knowledge of participants with regards to BF [46]. Participants who gave the ‘correct’ or ‘wrong’ answers to any of the 20 questions were given a score of 1 or 0, respectively. The total BF knowledge score was categorized into: less than 9 (poor BF knowledge); 9 − 11 (fair knowledge); 12 − 13 (good knowledge) and higher than 14 (very good knowledge) [46]. The validated Arabic version of the IIFAS was used to explore the participants’ attitudes towards BF. The IIFAS consists of 17 items with a five-point Likert scale that ranges from 1 (strongly disagree) to 5 (strongly agree) [47, 48]. The total BF attitude score ranged from 17 to 85 and was classified as a strong positive attitude toward formula feeding (a score of 17 − 52), positive attitude toward formula feeding (a score of 53 − 59), neutral attitude (a score of 60 − 75), positive attitude toward BF (a score of 76 − 82), and strong positive attitude toward BF (a score of 83 − 85) [48]. BF intentions were examined using the validated Arabic Infant Feeding Intention (IFI) Scale. The IFI scale includes five infant feeding statements with a five-point Likert scale ranging from 0 (very much disagree) to 4 (very much agree) [49, 50]. The total score ranged from 0 to 16, and was classified into weak (0 to 7.5), fair (8 to 11.5), strong (12 to 15.5), and very strong (greater than 16) [50].

- Infant feeding practices at four months after delivery (visit 4): Data for the infant feeding practices were obtained during a one-to-one interview at the participant’s home and included information on ever BF, early initiation of BF, as well as current feeding practices [4]. The mother was asked if she is still breastfeeding her child and if yes, if her child is exclusively breastfed. BF was considered exclusive (EBF) when the mother reported that she has been exclusively feeding her infant with breast milk since birth, with no additional water, fluids, formula milk or foods [51]. The mother was also asked if she had practiced early initiation of breastfeeding, which was defined as putting the infant to the breast within one hour of birth [52]. Infant feeding practices at six months after delivery (visit 5): Information related to BF and EBF were obtained during the fifth visit, using similar protocol to that of the fourth visit.

Statistical analysis

Frequencies and proportions as well as means ± standard deviation (SD) were used to described categorical and continuous variables, respectively. The feeding practices considered in this study were ever BF, BF initiation within the first hour after birth, BF at four months, EBF at four months, BF at six months, and EBF at six months. The answers of participants on each of the scales for exposure, knowledge, attitude, and intentions regarding BF were presented as frequencies and proportions. The total scores for knowledge, attitude, and intentions were computed and presented as means and SD as well as in categories as described earlier in this section. Simple and multiple logistic regressions were used to examine the determinants (sociodemographic and delivery characteristics) of feeding practices. The associations among exposure, knowledge, attitude, and intentions related to BF with feeding practices were also examined using simple and multiple logistic regression analyses. In all regression analyses the outcome variables were the feeding practices considered in this study. More specifically, the outcomes were ever BF (yes / no), BF initiation, EBF for four months, BF for four months and EBF for six months. For all analyses, predictor variables with a p-value of 0.2 in the simple regression were entered in the multiple regression models. All statistical analyses were carried out using Statistical Package for Social Sciences (SPSS) software 25 (SPSS Inc., Chicago, IL). P-values less than 0.05 were considered statistically significant.

Results

A flow chart describing the numbers of participants at each of the visits is presented in Fig. 2. The largest dropout rate was observed after the first visit, with lower dropout rates being noted after the visits at four and six months postpartum (Fig. 2).

Table 1 displays the sociodemographic characteristics of participants who completed the third visit (n = 230). The study population consisted of 135 Lebanese and 95 Qatari pregnant women. Almost 38% of participants were 30 years of age or older, and 61% had one or more children (aside from the current pregnancy) (Table 1).

Feeding practices in the study sample are presented in Fig. 3. The majority of participants indicated ever BF (95.8%), and 72.8% reported BF within the first hour after giving birth. Rates of BF were estimated at 70.3% at four months and 62.3% at six months, while those of EBF were estimated at 35.7% and 18.5% at four and six months, respectively (Fig. 3).

The exposure to BF among participants is presented in Table 2 and Fig. 4a. High exposure to BF was observed among 96.5% of participants, with the lowest exposure reported for the question about ever been breastfed (86.1%). Table 3 details the answers of study participants to the BFK-A. The lowest proportions of correct answers were noted for the following two questions: ‘After a baby loses weight following birth, he / she will probably gain it back faster if’ (correct option: He / she is bottle-fed) and ‘Because babies may get a bad reaction to certain foods, BF mothers should never eat’ (correct option: none of the options is correct. Other important knowledge gaps were related to the best way to identify if the baby is getting enough milk; BF and its impact on the mother’s lifestyle; and the impact of BF on breast shape. Interestingly only half of the participating women provided a correct answer related to the ability of women to make enough milk to feed their baby and related to breast milk making up a complete diet for a baby. Less than half of the women identified factors that could lead to sore nipples. On the other hand, most of the mothers acknowledged that breast milk is the best food for the newborn, and that they should try to breastfeed even if they are planning to go back to work or school (Table 3). Overall, 25.8% of participants had very good knowledge while 7% had poor knowledge of BF (Fig. 4b).

Distribution of breastfeeding (a) exposure, (b) knowledge, (c) attitude, and (d) intention among the MINA participants during the third trimester (n = 230) a, b, c, d.aA score of 0 or 1 indicates low exposure to breastfeeding, and a score of 2 or 3 indicates high exposure (Hamade et al., 2014). bA score less than 9 indicates poor breastfeeding knowledge, 9 to 11 indicates fair knowledge, 12 to 13 indicates good knowledge, and greater than 14 indicates very good knowledge (Tamim et al., 2016). cA score of 17 − 52 indicates strong negative attitude toward breastfeeding, 53 − 59 indicates negative attitude toward breastfeeding, 60–75 indicates neutral attitude, 76 − 82 positive attitude toward breastfeeding, and 83 − 85 strong positive attitude toward breastfeeding. (Charafeddine et al., 2016). dA score of 0 − 7.5 indicates weak breastfeeding intention, 8 − 11.5 indicates fair intentions, 12 − 15.5 indicates strong intentions, and greater than 16 very strong intentions (Yehya et al., 2017)

The attitudes and intentions to BF of study participants, as examined by the IIFAS and the IFI Scale are presented in Table 4 and Figs. 4c and 4d. For the attitude, the statements with the lowest means ± SD were ‘A mother who occasionally drinks alcohol should not breastfeed her baby’ and ‘The nutritional benefits of breast milk last only until the baby is weaned from breast milk’. In addition, more than half of the participants disagreed that formula feeding is the better choice for women who plan to work (52.8%) and that women should not breastfeed in public places (53.7%). The overall attitude score showed a sizeable proportion of participants (67.1%) reporting a neutral attitude, with only 1% displaying a strong positive attitude to BF and 5.7% having strong negative attitudes to BF (Fig. 4c). For the intention to breastfeed, 43.4% of women had very strong intentions to breastfeed, 25.4% had strong intentions, 18.4% fair intentions and 12.7% weak intentions (Fig. 4d).

The age-adjusted associations of sociodemographic and birth characteristics with BF practices, as derived from logistic regression, are presented in Table 5. After adjustment, using multiple regression, the following variables retained significance in predicting BF practices: Belonging to the Qatari arm of the cohort women were more likely to initiate BF as compared to their Lebanese counterparts (OR 3.47: 95% CI 1.07, 11.21); mothers having one or more children were more likely to continue BF until the fourth and sixth months (OR 2.82: 95% CI 1.19, 6.67 and OR 3.37; 95% CI 1.24, 9.21, respectively), while mothers having a crowding index of one or greater were less likely to do so (OR 0.31; 95% CI 0.13, 0.71 and OR 0.24; 95% CI: 0.09, 0.65, respectively); and employment was associated with lower odds of BF at four months (OR 0.43; 95% CI 0.2, 0.93). Women who experienced no complications during delivery were more likely to exclusively breastfeed at six months as compared to mother who had complications (OR 2.64; 95% CI 1.09, 6.44) (Data shown in Additional file 1).

Multiple logistic regressions for the associations of exposure, knowledge, attitude, and intentions related to breastfeeding with feeding practices are presented in Table 6. A high exposure to breastfeeding was associated with greater odds of BF initiation. Knowledge about breastfeeding was not associated with any of the breastfeeding practices. Both positive attitude towards breastfeeding and strong intention to breastfeed were associated with EBF at four months, breastfeeding at four months, and breastfeeding at six months (Table 6).

Discussion

This study is the first from the EMR to investigate maternal breastfeeding knowledge, attitude, and intention prenatally, and their association with actual feeding practices during the first six months postnatally. It showed that only 25% of women participating in the MINA cohort had very good knowledge, and 9.2% reported a positive / strong positive attitude towards breastfeeding, while the majority (96.5%) reported high previous exposure to breastfeeding. Even though the majority of participating women (70%) reported a strong intention to breastfeed, and actually initiated BF within the first hour after birth (72.8%), a sizable proportion could not meet the WHO recommendations in terms of EBF and breastfeeding duration. In fact, only 18.5% of participating women were able to exclusively breastfeed their baby for six months postpartum. The study showed that both a positive attitude towards breastfeeding and strong intention to breastfeed were independent predictors of EBF at four months, as well as breastfeeding at four and six months, while breastfeeding knowledge was not associated with any of the breastfeeding outcomes.

The observed high rate of early breastfeeding initiation in our cohort (72.8%) is comparable to previous estimates reported from Lebanon (77%) [50], while exceeding those reported from Qatar (57%) [53]. Despite these high initiation rates, the prevalence of EBF for six months was low, estimated at 18.5% in the study sample. This low prevalence confirms previous data described in Lebanon (10.1 − 26.6% EBF) [37, 40, 54, 55] and Qatar (18.9 − 26%) [37, 41], while showing that EBF rates in these two countries are lower than the average for the EMR as well as the global average (29.3% and 42%, respectively) [9, 37, 56]. The sharp decrease in the rates of EBF from 35.7% at four months to 18.5% at six months has been described by previous studies conducted in both Lebanon and Qatar [33, 57].

The study findings identified several sociodemographic attributes that were associated with infant feeding practices in the study sample. In agreement with previous studies conducted in Lebanon, Qatar [23, 33, 57], and elsewhere [34], maternal employment was associated with lower odds of breastfeeding. Similarly, women with a lower SES (as assessed by a crowding index ≥ 1) had lower odds of breastfeeding compared to those with higher SES, a finding that is in line with previous reports in the literature [58], highlighting the numerous social and environmental factors that contribute to the complex decision on infant feeding [10, 59]. The fact that participants from Qatar were more likely to initiate breastfeeding compared to their Lebanese counterparts may be a reflection of the higher SES in Qatar, or alternatively a reflection of the higher breastfeeding support within the hospital sites in Qatar compared to Lebanon [60]. In our study, mothers having one or more children were more likely to continue BF until the fourth and sixth month, which is consistent with earlier findings reported from Qatar [23], Lebanon [61], the United Arab Emirates (UAE) [62], as well as several other studies [63,64,65]. Higher parity may in fact be linked to better experience and enhanced maternal self-confidence, thus contributing to higher breastfeeding rates and longer breastfeeding duration [61].

Besides the demographic and socioeconomic factors that may modulate infant feeding decisions, it has been proposed that personal psychosocial factors and previous exposure to breastfeeding are important determinants of breastfeeding practices [27]. Several cross-sectional studies conducted among pregnant women have shown a direct association between breastfeeding exposure, knowledge, and attitude, with the intention to breastfeeding prenatally [20, 23, 29, 33]. However, few studies have investigated, longitudinally, the association between these maternal prenatal attributes and actual breastfeeding practices postnatally [22, 34]. Interestingly, the findings of our study showed that the proportions of women who had very good breastfeeding knowledge (25%) or positive / strong positive attitude towards breastfeeding (9.2%) were considerably lower than those practicing adequate breastfeeding practices such as early initiation of breastfeeding (72.8%) and breastfeeding at four and six months (70.3% and 62.3%).

In other instances in the literature, opposite findings were reported such as those described by Mogre et al. [66] and by Osibogun et al. [67], where high proportions of mothers displayed favorable breastfeeding knowledge and attitudes, but engaged in suboptimal breastfeeding practices. A direct association between breastfeeding practices and psychosocial factors is therefore not always observed, and the relationship between these constructs may be more complex than a simple lock-step relationship. Indeed, factors like breastfeeding protection and support as well as social normalization of breastfeeding may be more important than maternal breastfeeding knowledge [68]. In our study, antenatal breastfeeding knowledge was not associated with any of the investigated postnatal feeding practices, which lends further support to the complex relation between these constructs [69, 70]. In contrast, prior exposure to breastfeeding, which can be reflective of some form of social normalization of breastfeeding, was associated with a ten-fold increase in the odds of breastfeeding initiation among the cohort participants. Prior exposure to breastfeeding, such as the type of feeding women received from their own mothers, may in fact enhance the cultural acceptability of breastfeeding and contribute to more favorable attitudes towards this feeding modality [71, 72].

Our study findings showed that a positive attitude towards breastfeeding was associated with approximately a three-fold increase in EBF and breastfeeding at four months, and with a four-fold increase in the odds of breastfeeding at six months. In line with our findings, previous research has shown that improving maternal attitude and behavioral perceptions toward breastfeeding can significantly increase the likelihood of breastfeeding and improve its duration [73,74,75,76]. In the longitudinal US Infant feeding Practices Study II where breastfeeding attitude was assessed based on the perceived importance of EBF for the first six months, women who strongly valued EBF had more than twice the odds of EBF for three months and for six months compared to those with negative perceived value towards EBF [34]. A worrisome observation in our study is the fact that close to 70% of participating women displayed a neutral attitude towards breastfeeding, with only 1% displaying a strong positive attitude.

Recognizing that maternal attitude towards breastfeeding may be modifiable, these findings highlight the need for BF intervention programs that place a strong focus on prenatal breastfeeding attitudes and the value that mothers consign to breastfeeding [34]. In this context, our study identified specific items within the IIFAS that were particularly associated with a negative attitude, and that can be the target of future interventions. These essentially pertained to breastfeeding in public and the convenience of breastfeeding for a working mother, with more than half of participants stating that women should not breastfeed in public, and that formula feeding is more convenient than breastfeeding for working mothers. Interestingly, the negative attitude towards breastfeeding in public and towards the suitability of BF for working mothers were reported by a previous study conducted among undergraduate female students in Lebanon, showing how deep these negative perceptions are engraved within the local culture [45]. These negative attitudes may result from the dominating societal disapproval and the stigmatization of breastfeeding in public places, rendering it taboo in the Arab culture [45]. The negative attitude toward breastfeeding in working mothers, is worrisome, given that women are increasingly part of the labor force in both Lebanon and Qatar [33, 77].

In line with previous research showing that the intention to breastfeed is a well-established determinant of BF behavior, and particularly EBF [34, 78, 79], our study showed that a strong intention to breastfeed was associated with a three-fold increase in the odds of EBF and breastfeeding at four months, and with a four-fold increase in the odds of breastfeeding at six months. Hamade et al. [36] have also previously highlighted the intention to breastfeed as one of the significant predictors of EBF among Lebanese mothers. In a study conducted in the US, DiGirolamo et al. investigated the effects of prenatal intention on breastfeeding initiation and duration and showed that prenatal intention was a significant predictor of positive BF practices postnatally [79]. However, the study by DiGirolamo et al. also showed that, in addition to prenatal intention, the initial breastfeeding experiences of the mother were significantly associated with breastfeeding outcomes, and particularly with early termination.

This may explain the intention vs behavior gap that was reported by several previous investigations [22, 34], and was also a main observation in our study. In fact, although close to 70% of women participating in the MINA cohort had expressed a strong or very strong intention to breastfeed their baby, only 18.5% had exclusively breastfed for six months and 35.7% for four months. These findings suggest that women’s initial intention, assessed during pregnancy, can potentially change throughout the six months period postnatally. Mothers may in fact be challenged postnatally, by certain environmental barriers to breastfeeding such as the lack of support at home, workplace, or hospitals [22, 34] or by emotional and psychological barriers [22, 79]. According to Rothman’s (2000) [80], the factors that lead to behavioral intention or initiation differ from those leading to behavioral maintenance, the latter being influenced not only by intention but also by perceived satisfaction with the outcome [80]. For example, DiGirolamo et al. [79] showed that women with a relatively negative initial experience with BF, such as problems or complications during the first week or a reported lack of comfort, were less likely to continue breastfeeding by ten weeks postpartum. In a qualitative study, Ahishakiye et al. also reported that postnatal discomfort, personal confidence in the ability to breastfeed, and perceived breastmilk insufficiency were among the factors that modulated breastfeeding behavior postnatally [22].

The possibility that environmental or psychological barriers may emerge and affect breastfeeding behavior postnatally may also explain why, in our study, breastfeeding knowledge, which was previously shown to be associated with breastfeeding intention or positive breastfeeding outcomes [74,75,76,77,78,79,80,81,82,83] was not found to predict breastfeeding behavior among MINA participants. There is a need for future studies that provide an-in-depth appraisal of factors that could lead to improvements in BF outcomes postnatally and identify context-specific barriers and facilitators.

The strengths of this study include its prospective nature, thus minimizing recall bias that is often associated with cross-sectional studies. Furthermore, despite the MINA cohort being a multi-country cohort, the study protocols and data collection procedures were standardized across both study sites [38]. However, the results of this study ought to be considered in view of the following limitations. First, the small sample size in our cohort may have led to underpowered analyses. Second, psychosocial characteristics and feeding practices were assessed using questionnaires that were administered in an interview setting. As is the case with most questionnaire-based studies, the interview-based approach may result in social desirability bias [84]. In our study, all interviewers had received extensive training prior to the initiation of data collection in order to minimize judgmental verbal and nonverbal communication and consequently reduce the likelihood of social desirability bias.

Conclusions

In conclusion, this study documented suboptimal knowledge and attitude towards breastfeeding in a sample of Middle Eastern women, coupled with low rates of EBF. While knowledge was not associated with breastfeeding practices, a high prior exposure, a positive breastfeeding attitude, and a strong intention to breastfeed prenatally were significant predictors of breastfeeding practices postnatally. Interestingly, although close to 70% of women had expressed a strong intention to breastfeed, only 18.5% had exclusively breastfed for six months, a finding that may reflect the challenges encountered postnatally by women, and which often include poor self-efficacy, and / or lack of support at home, workplace, or hospitals [85].

Taken together, the study findings highlight the need for developing specific interventions and policies aimed at protecting, supporting and normalizing breastfeeding as a social norm, and improving breastfeeding attitudes among women, while tailoring these interventions to the local context and culture. By abating societal taboos and promoting breastfeeding, such interventions may play a central role in addressing the prevalent negative attitudes such as the issue of BF in public and the suitability of breastfeeding for a working mother. The study results also highlight the need to better understand what influences prenatal breastfeeding intentions, given that it was shown to be an important predictor of a mother’s behavior after delivery [79]. It is through the investment in BF and enhanced infant nutrition that countries step towards the path of building their human capital, developing their economies, and shaping their future prosperity [86].

Availability of data and materials

The datasets used and / or analysed during the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

Abbreviations

- BF:

-

Breastfeeding

- BFK-A:

-

Breastfeeding Knowledge Questionnaire

- CI:

-

Confidence interval

- CI:

-

Crowding index

- EBF:

-

Exclusive breastfeeding

- EMR:

-

Eastern Mediterranean Region

- IFI:

-

Infant Feeding Intention

- IIFAS:

-

Iowa Infant Feeding Attitude Scale

- MINA:

-

Mother and Infant Nutritional Assessment

- NCDs:

-

Non-communicable diseases

- SD:

-

Standard deviation

- SES:

-

Socioeconomic status

- UAE:

-

United Arab Emirates

- US:

-

United States

- WHO:

-

World Health Organization

References

Kuh D, Ben-Shlomo Y, Lynch J, Hallqvist J, Power C. Life course epidemiology. J Epidemiol Community Health. 2003;57(10):778–83. https://doi.org/10.1136/jech.57.10.778.

Kelishadi R, Farajian S. The protective effects of breastfeeding on chronic non-communicable diseases in adulthood: A review of evidence. Adv Biomed Res. 2014;3. https://doi.org/10.4103/2277-9175.124629.

Grummer-Strawn LM, Rollins N. Summarising the health effects of breastfeeding. Acta Paediatr. 2015;104(467):1–2. https://doi.org/10.1111/apa.13136.

World Health Organization. Indicators for assessing infant and young child feeding practices: part 1: definitions: conclusions of a consensus meeting held 6–8 November 2007. 2008. Washington DC, USA: World Health Organization. http://www.apps.who.int/iris/bitstream/handle/10665/43895/9789242596663_fre.pdf.

Duijts L, Jaddoe VW, Hofman A, Moll HA. Prolonged and exclusive breastfeeding reduces the risk of infectious diseases in infancy. Pediatrics. 2010;126(1):e18–25. https://doi.org/10.1542/peds.2008-3256.

Chantry CJ, Howard CR, Auinger P. Full breastfeeding duration and associated decrease in respiratory tract infection in US children. Pediatrics. 2006;117(2):425–32. https://doi.org/10.1542/peds.2004-2283.

Kramer MS, Aboud F, Mironova E, Vanilovich I, Platt RW, Matush L, et al. Breastfeeding and child cognitive development: new evidence from a large randomized trial. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 2008;65(5):578–84. https://doi.org/10.1001/archpsyc.65.5.578.

Dewey KG. Huffman SL. Maternal, infant, and young child nutrition: combining efforts to maximize impacts on child growth and micronutrient status. 2009;39(2 Suppl):S187–9. https://doi.org/10.1177/15648265090302S201.

Victora CG, Bahl R, Barros AJ, França GV, Horton S, Krasevec J, et al. Breastfeeding in the 21st century: epidemiology, mechanisms, and lifelong effect. Lancet. 2016;387(10017):475–90. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0140-6736(15)01024-7.

Mattar L, Hobeika M, Zeidan RK, Salameh P, Issa C. Determinants of exclusive and mixed breastfeeding durations and risk of recurrent illnesses in toddlers attending day care programs across Lebanon. J Pediatr Nurs. 2019;45:e24–34. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.pedn.2018.12.015.

Issa C, Hobeika M, Salameh P, Zeidan RK, Mattar L. Longer durations of both exclusive and mixed breastfeeding are associated with better health in infants and toddlers. Breastfeed Rev. 2019;27(2):17–27.

El Din EMS, Rabah TM, Metwally AM, Nassar MS, Elabd MA, Shalaan A, et al. Potential risk factors of developmental cognitive delay in the first two years of life. Open Access Maced J Med Sci. 2019;7(12):2024–30. https://doi.org/10.3889/oamjms.2019.566.

Metwally AM, Salah El-Din EM, Shehata MA, Shaalan A, El Etreby LA, Kandeel WA, et al. Early life predictors of socio-emotional development in a sample of Egyptian infants. PLoS ONE. 2016;11(7): e0158086. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0158086.

El-Din EMS, Elabd MA, Nassar MS, Metwally AM, Abdellatif GA, Rabah TM, et al. The interaction of social, physical and nutritive factors in triggering early developmental language delay in a sample of egyptian children. Open Access Maced J Med Sci. 2019;7(17):2767–74. https://doi.org/10.3889/oamjms.2019.642.

Imdad A, Yakoob MY, Bhutta ZA. Effect of breastfeeding promotion interventions on breastfeeding rates, with special focus on developing countries. BMC Public Health. 2011;11(Suppl 3):S24. https://doi.org/10.1186/1471-2458-11-S3-S24.

United Nations Children's Fund, World Health Organization. Breastfeeding Advocacy Initiative: For the Best Start in Life. WHO/NMH/NHD/15.1. 2015. http://www.sites.unicef.org/nutrition/files/Breastfeeding_Advocacy_Strategy-2015.pdf.

World Health Organization and UNICEF. Global nutrition targets 2025: breastfeeding policy brief. 2014. Geneva, Switzerland: World Health Organization. http://www.apps.who.int/iris/bitstream/handle/10665/149022/WHO_NMH_NHD_14.7_eng.pdf?ua=1.

Dykes F. Breastfeeding in hospital: mothers, midwives and the production line. London: Routledge; 2006.

Goulet C, Lampron A, Marcil I, Ross L. Attitudes and subjective norms of male and female adolescents toward breastfeeding. J Hum Lact. 2003;19(4):402–10. https://doi.org/10.1177/0890334403258337.

Senghore T, Omotosho TA, Ceesay O, Williams DCH. Predictors of exclusive breastfeeding knowledge and intention to or practice of exclusive breastfeeding among antenatal and postnatal women receiving routine care: a cross-sectional study. Int Breastfeed J. 2018;13:9. https://doi.org/10.1186/s13006-018-0154-0.

Thomas JS, Elaine AY, Tirmizi N, Owais A, Das SK, Rahman S, et al. Maternal knowledge, attitudes and self-efficacy in relation to intention to exclusively breastfeed among pregnant women in rural Bangladesh. Matern Child Health J. 2015;19(1):49–57. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10995-014-1494-z.

Ahishakiye J, Bouwman L, Brouwer ID, Vaandrager L, Koelen M. Prenatal infant feeding intentions and actual feeding practices during the first six months postpartum in rural Rwanda: a qualitative, longitudinal cohort study. Int Breastfeed J. 2020;15:29. https://doi.org/10.1186/s13006-020-00275-y.

Nasser A, Omer F, Al-Lenqawi F, Al-Awwa R, Khan T, El-Heneidy A, et al. Predictors of continued breastfeeding at one year among women attending primary healthcare centers in Qatar: A cross-sectional study. Nutrients. 2018;10(8):983. https://doi.org/10.3390/nu10080983.

Cattaneo A. Academy of breastfeeding medicine founder’s lecture 2011: inequalities and inequities in breastfeeding: an international perspective. Breastfeed Med. 2012;7(1):3–9. https://doi.org/10.1089/bfm.2012.9999.

Krishnendu M, Devaki G. Knowledge, attitude and practice towards breasfeeding among lactating mothers in rural areas of Thrissur District of Kerala, India: a cross-sectional study. Biomed Pharmacol J. 2017;10(2):683–90. https://doi.org/10.13005/bpj/1156.

Labbok M, Taylor E. Achieving exclusive breastfeeding in the United States: findings and recommendations. 2008. Washington DC, USA: United States Breastfeeding Committee. http://www.usbreastfeeding.org/p/cm/ld/fid=197.

Kanhadilok S, McGrath JM. An integrative review of factors influencing breastfeeding in adolescent mothers. J Perinat Educ. 2015;24(2):119–27. https://doi.org/10.1891/1946-6560.24.2.119.

Kandeel WA, Rabah TM, Zeid DA, El-Din EMS, Metwally AM, Shaalan A, et al. Determinants of exclusive breastfeeding in a sample of Egyptian infants. Open Access Maced J Med Sci. 2018;6(10):1818–23. https://doi.org/10.3889/oamjms.2018.359.

Khasawneh W, Kheirallah K, Mazin M, Abdulnabi S. Knowledge, attitude, motivation and planning of breastfeeding: a cross-sectional study among Jordanian women. Int Breastfeed J. 2020;15:60. https://doi.org/10.1186/s13006-020-00303-x.

Dodgson JE, Henly SJ, Duckett L, Tarrant M. Theory of planned behavior-based models for breastfeeding duration among Hong Kong mothers. Nurs Res. 2003;52(3):148–58. https://doi.org/10.1097/00006199-200305000-00004.

Kavanagh K, Lou Z, Nicklas J, Habibi M, Murphy L. Breastfeeding knowledge, attitudes, prior exposure, and intent among undergraduate students. J Hum Lact. 2012;28(4):556–64. https://doi.org/10.1177/0890334412446798.

Sheeham A, Schmied V. The need for strategies that support women who are breastfeeding. Infant feeding practices: a cross-cultural perspective. Liamputtong P ed. London, UK: Springer; 2011. p. 70–2.

Hendaus MA, Alhammadi AH, Khan S, Osman S, Hamad A. Breastfeeding rates and barriers: a report from the state of Qatar. Int J Womens Health. 2018;10:467–75. https://doi.org/10.2147/IJWH.S161003.

Nnebe-Agumadu UH, Racine EF, Laditka SB, Coffman MJ. Associations between perceived value of exclusive breastfeeding among pregnant women in the United States and exclusive breastfeeding to three and six months postpartum: a prospective study. Int Breastfeed J. 2016;11:8. https://doi.org/10.1186/s13006-016-0065-x.

Odom EC, Li R, Scanlon KS, Perrine CG, Grummer-Strawn L. Reasons for earlier than desired cessation of breastfeeding. Pediatrics. 2013;131(3):e726–32. https://doi.org/10.1542/peds.2012-1295.

Hamade H, Chaaya M, Saliba M, Chaaban R, Osman H. Determinants of exclusive breastfeeding in an urban population of primiparas in Lebanon: a cross-sectional study. BMC Public Health. 2013;13:702. https://doi.org/10.1186/1471-2458-13-702.

Nasreddine L, Ayoub JJ, Al JA. Review of the nutrition situation in the Eastern Mediterranean Region. East Mediterr Health J. 2018;24(1):77–91.

Naja F, Nasreddine L, Yunis K, Clinton M, Nassar A, Jarrar SF, et al. Study protocol: mother and infant nutritional assessment (MINA) cohort study in Qatar and Lebanon. BMC Pregnancy Childbirth. 2016;16:98. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12884-016-0864-5.

Abdulmalik MA, Ayoub JJ, Mahmoud A, collaborators M, Nasreddine L, Naja F. Pre-pregnancy BMI, gestational weight gain and birth outcomes in Lebanon and Qatar: Results of the MINA cohort. PloS One. 2019;14(7):e0219248. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0219248.

Chehab RF, Nasreddine L, Zgheib R, Forman MR. Exclusive breastfeeding during the 40-day rest period and at six months in Lebanon: a cross-sectional study. Int Breastfeed J. 2020;15:45. https://doi.org/10.1186/s13006-020-00289-6.

Hendaus M, Alhammadi A, Khan S, Osman S, Hamad A. The influence of husbands on exclusive breastfeeding: A report form the Arab State of Qatar. Am Acad Pediatrics. 2019;144(2_MeetingAbstract):274. https://doi.org/10.1542/peds.144.2MA3.274.

Raosoft. Sample size calculator. http://www.raosoft.com/samplesize.html. Accessed 23 November 2021.

Melki I, Beydoun H, Khogali M, Tamim H, Yunis K. Household crowding index: a correlate of socioeconomic status and inter-pregnancy spacing in an urban setting. J Epidemiol Community Health. 2004;58(6):476–80. https://doi.org/10.1136/jech.2003.012690.

World Health Organization. ICD-10 : international statistical classification of diseases and related health problems : tenth revision, 2nd ed. 2004. Geneva, Switzerland: World Health Organization. http://www.apps.who.int/iris/handle/10665/42980.

Hamade H, Naja F, Keyrouz S, Hwalla N, Karam J, Al-Rustom L, et al. Breastfeeding knowledge, attitude, perceived behavior, and intention among female undergraduate university students in the Middle East: the case of Lebanon and Syria. Food Nutr Bull. 2014;35(2):179–90. https://doi.org/10.1177/156482651403500204.

Tamim H, Ghandour LA, Shamsedine L, Charafeddine L, Nasser F, Khalil Y, et al. Adaptation and validation of the Arabic version of the infant breastfeeding knowledge questionnaire among Lebanese women. J Hum Lact. 2016;32(4):682–8.

Mora Adl, Russell D, Dungy C, Losch M, Dusdieker L. The Iowa infant feeding attitude scale: analysis of reliability and validity 1. J Appl Soc Psychol. 1999;29(11):2362 80.

Charafeddine L, Tamim H, Soubra M, de la Mora A, Nabulsi M, Research, et al. Validation of the Arabic version of the Iowa Infant Feeding Attitude scale among Lebanese women. J Hum Lact. 2016;32(2):309–14.

Nommsen-Rivers L, Dewey K. Development and validation of the infant feeding intentions scale. Matern Child Health J. 2009;13(3):334–42.

Yehya N, Tamim H, Shamsedine L, Ayash S, Abdel Khalek L, Abou Ezzi A, et al. Validation of the Arabic version of the Infant Feeding Intentions Scale among Lebanese women. J Hum Lact. 2017;33(2):383–9. https://doi.org/10.1177/0890334416680790.

World Health Organization. e-Library of Evidence for Nutrition Actions (eLENA): Exclusive breastfeeding for optimal growth, development and health of infants. https://www.who.int/elena/titles/exclusive_breastfeeding/en/#:~:text=Breastfeeding%20has%20many%20health%20benefits%20for%20both%20the%20mother%20and%20infant.&text=Exclusive%20breastfeeding%20means%20that%20the,of%20vitamins%2C%20minerals%20or%20medicines. Accessed 1 Feb 2021.

World Health Organization. Indicators for assessing infant and young child feeding practices: definitions and measurement methods. 2011. Geneva, Switzerland: World Health Organization the United Nations Children’s Fund (UNICEF). https://apps.who.int/iris/bitstream/handle/10665/340706/9789240018389-eng.pdf?sequence=1.

Al-Kohji S, Said HA, Selim NA. Breastfeeding practice and determinants among Arab mothers in Qatar. Saudi Med J. 2012;33(4):436–43.

Central Administration of Statistics, United Nations Children's Fund. Multiple Indicators Cluster Survey round 3 (MICS3). http://www.cas.gov.lb/images/Mics3/CAS_MICS3_survey_2009.pdf. Accessed 5 February 2018.

Central Bureau of Statistics, United Nations Children's Fund. Preliminary report on the Multiple Cluster Survey on the Situation of Children in Lebanon. http://www.mics.unicef.org/surveys. Accessed 27 June 2017.

United Nations Children's Fund, World Health Organization. Tracking Progress for Breastfeeding Policies and Programmes. 2017. https://www.who.int/nutrition/publications/infantfeeding/global-bf-scorecard-2017.pdf.

Nabulsi M. Why are breastfeeding rates low in Lebanon? A qualitative study BMC Pediatr. 2011;11:75. https://doi.org/10.1186/1471-2431-11-75.

Ajami M, Abdollahi M, Salehi F, Oldewage-Theron W, Jamshidi-Naeini Y. The association between household socioeconomic status, breastfeeding, and infants’ anthropometric indices. Int J Prev Med. 2018;9(1):89. https://doi.org/10.4103/ijpvm.IJPVM_52_17.

Pisacane A, Continisio GI, Aldinucci M, D’Amora S, Continisio P. A controlled trial of the father’s role in breastfeeding promotion. Pediatrics. 2005;116(4):e494–8.

World Health Organization. National Implementation of the Baby-friendly Hospital Initiative, 2017. 2017. Geneva.

Al-Sahab B, Tamim H, Mumtaz G, Khawaja M, Khogali M, Afifi R, et al. Predictors of breast-feeding in a developing country: results of a prospective cohort study. Public Health Nutr. 2008;11(12):1350–6. https://doi.org/10.1017/S1368980008003005.

Radwan H. Patterns and determinants of breastfeeding and complementary feeding practices of Emirati Mothers in the United Arab Emirates. BMC Public Health. 2013;13:171.

Amin T, Hablas H, Al Qader AA. Determinants of initiation and exclusivity of breastfeeding in Al Hassa. Saudi Arabia Breastfeed Med. 2011;6(2):59–68.

Forde KA, Miller LJ. 2006–07 north metropolitan Perth breastfeeding cohort study: how long are mothers breastfeeding? Breastfeed Rev. 2010;18(2):14–24.

Kitano N, Nomura K, Kido M, Murakami K, Ohkubo T, Ueno M, et al. Combined effects of maternal age and parity on successful initiation of exclusive breastfeeding. Prev Med Rep. 2016;3:121–6.

Mogre V, Dery M, Gaa PK. Knowledge, attitudes and determinants of exclusive breastfeeding practice among Ghanaian rural lactating mothers. Int Breastfeed J. 2016;11:12. https://doi.org/10.1186/s13006-016-0071-z.

Osibogun OO, Olufunlayo TF, Oyibo SO. Knowledge, attitude and support for exclusive breastfeeding among bankers in Mainland Local Government in Lagos State. Nigeria Int Breastfeed J. 2018;13:38. https://doi.org/10.1186/s13006-018-0182-9.

Hawley NL, Rosen RK, Strait EA, Raffucci G, Holmdahl I, Freeman JR, et al. Mothers’ attitudes and beliefs about infant feeding highlight barriers to exclusive breastfeeding in American Samoa. Women Birth. 2015;28(3):e80–6. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.wombi.2015.04.002.

Onah S, Osuorah DIC, Ebenebe J, Ezechukwu C, Ekwochi U, Ndukwu I. Infant feeding practices and maternal socio-demographic factors that influence practice of exclusive breastfeeding among mothers in Nnewi South-East Nigeria: a cross-sectional and analytical study. Int Breastfeed J. 2014;9:6. https://doi.org/10.1186/1746-4358-9-6.

Asare BY-A, Preko JV, Baafi D, Dwumfour-Asare B. Breastfeeding practices and determinants of exclusive breastfeeding in a cross-sectional study at a child welfare clinic in Tema Manhean, Ghana. Int Breastfeed J. 2018;13:12. https://doi.org/10.1186/s13006-018-0156-y.

DeMaria AL, Ramos-Ortiz J, Basile K. Breastfeeding trends, influences, and perceptions among Italian women: a qualitative study. Int J Qual Stud Health Well-being. 2020;15(1):1734275.

Scott JA, Shaker I, Reid M. Parental attitudes toward breastfeeding: their association with feeding outcome at hospital discharge. Birth. 2004;31(2):125–31.

Ahluwalia IB, Morrow B, Hsia J. Why do women stop breastfeeding? Findings from the Pregnancy Risk Assessment and Monitoring System. Pediatrics. 2005;116(6):1408–12.

Chezem J, Friesen C, Boettcher J. Breastfeeding knowledge, breastfeeding confidence, and infant feeding plans: effects on actual feeding practices. J Obstet Gynecol Neonatal Nurs. 2003;32(1):40–7.

Dennis CL. Breastfeeding initiation and duration: A 1990–2000 literature review. J Obstet Gynecol Neonatal Nurs. 2002;31(1):12–32.

Li R, Fridinger F, Grummer-Strawn L. Public perceptions on breastfeeding constraints. J Hum Lact. 2002;18(3):227–35.

Khalaf M. The Lebanese woman and the labor market. Al-Raida Journal. 1993;10(61):14–7.

Bai YK, Middlestadt S, Joanne Peng CY, Fly A. Psychosocial factors underlying the mother’s decision to continue exclusive breastfeeding for 6 months: an elicitation study. J Acad Nutr Diet. 2009;22(2):134–40.

DiGirolamo A, Thompson N, Martorell R, Fein S, Grummer-Strawn L. Intention or experience? Predictors of continued breastfeeding. Health Educ Behav. 2005;32(2):208–26.

Rothman AJ. Toward a theory-based analysis of behavioral maintenance. Health Psychol. 2000;19(1S):64.

Kornides M, Kitsantas P. Evaluation of breastfeeding promotion, support, and knowledge of benefits on breastfeeding outcomes. J Child Health Care. 2013;17(3):264–73.

Persad MD, Mensinger JL. Maternal breastfeeding attitudes: association with breastfeeding intent and socio-demographics among urban primiparas. J Community Health. 2008;33(2):53–60.

Voramongkol N, Phupong V. A randomized controlled trial of knowledge sharing practice with empowerment strategies in pregnant women to improve exclusive breastfeeding during the first six months postpartum. J Med Assoc Thai. 2010;93(9):1009–18.

Okamoto K, Ohsuka K, Shiraishi T, Hukazawa E, Wakasugi S, Furuta K. Comparability of epidemiological information between self-and interviewer-administered questionnaires. J Clin Epidemiol. 2002;55(5):505–11.

Marcon AR, Bieber M, Azad MB. Protecting, promoting, and supporting breastfeeding on Instagram. Matern Child Nutr. 2019;15(1): e12658. https://doi.org/10.1111/mcn.12658.

United Nations Children's Fund, World Health Organization, 1000 Days, Alive & Thrive. Nurturing the Health and Wealth of Nations: The Investment Case for Breastfeeding. 2017. https://www.who.int/nutrition/publications/infantfeeding/global-bf-collective-investmentcase.pdf?ua=1.

Acknowledgements

The authors would like to acknowledge the MINA collaborators including Dr. Nahla Hwalla, Dr. Ghina Ghazeeri, Dr. Anwar Nassar, Dr. Khalid Yunis, Dr. Saadeddine Itani, Dr. Al Anoud Al Thani, Dr. Zelaikha Bashwar, Dr. Hiba Bawadi.

Funding

This research was supported by the Qatar National Research Fund (QNRF) under the National Priorities Research Program (NPRP 6–247-3–061). The funder had no role in the design of the study and collection, analysis, and interpretation of data and in writing the manuscript.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Consortia

Contributions

LN: conceptualization, investigation, supervision, writing – original draft, review and editing; AC: data curation; JA: data curation, formal analysis, investigation, methodology, project administration, writing original draft; NA: formal analysis; AM: data curation, investigation, project administration; MAA: data curation, investigation, supervision, FN: conceptualization, funding acquisition, formal analysis, methodology, supervision, writing – original draft, review and editing. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate

The protocols used in the MINA cohort were reviewed and approved by two independent research ethics boards: the Institutional Review Board at the American University of Beirut (Protocol ID: NUT. FN. 12) and the Primary Health Care Corporation in Qatar (Protocol ID: PHCC / RC / 15 / 04 / 006). All MINA participants provided a written signed consent form.

Consent for publication

Not applicable

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary Information

Additional file 1.

Multiple logistic regression analysis of the association between socio-demographic characteristics and birth outcomes (explanatory variables) and feeding practices (outcome variables). Values in this table represent OR and their corresponding 95%CI,ORs with a bold font are statistically significant. aIncludingtechnical diploma.BFbreastfeeding, CI confidence interval, EBF exclusivebreastfeeding, OR odds ratio; ref: reference category

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/. The Creative Commons Public Domain Dedication waiver (http://creativecommons.org/publicdomain/zero/1.0/) applies to the data made available in this article, unless otherwise stated in a credit line to the data.

About this article

Cite this article

Naja, F., Chatila, A., Ayoub, J.J. et al. Prenatal breastfeeding knowledge, attitude and intention, and their associations with feeding practices during the first six months of life: a cohort study in Lebanon and Qatar. Int Breastfeed J 17, 15 (2022). https://doi.org/10.1186/s13006-022-00456-x

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/s13006-022-00456-x