Abstract

Background

Maternal smoking is suspected to have negative impacts on breastfeeding, such as decreasing the quantity of breast milk, and reducing vitamin and fat concentrations in the milk in the late lactation period. Cigarette and water pipe tobacco products are widely used in Jordan. We aimed to estimate the association between use of different tobacco products and the rates of current breastfeeding.

Methods

Data from Jordan’s Population and Family Health Surveys 2012 and 2017–18 were examined. Last-born, living children, aged < 25 months, from singleton births, ever breastfed, and living with their mother were included. The key outcome variables were the current breastfeeding (during last 24 h) and tobacco usage status [water pipe tobacco (hookah or narghile) and/or cigarette tobacco]. Complex sample multivariate logistic regression analysis was used to evaluate the association of the current breastfeeding with maternal smoking status.

Results

Overall, 6726 infants were included in the study. The current breastfeeding rate in infants aged 0–6 months was 87%, compared with 43.9% in infants aged 12–17 months and 19.4% in infants aged 18–24 months. Overall, 4.4% had mothers who smoked cigarettes, 5.4% smoked water pipe, and 1.6% both cigarettes and water pipe. The proportion of breastfed infants in non-smoking mothers was 57.7% and, those in smoke water pipe, cigarette and both tobacco products were 55.4, 44.9, and 51.0% respectively. Univariate analysis revealed that women cigarette smokers had a lower odds ratio (OR) for current breastfeeding (OR 0.60, 95% Confidence Interval [CI] 0.39, 0.92). Multivariate analysis revealed that maternal cigarette smoking was associated with a lower odds ratio for current breastfeeding compared with mothers who smoked neither water pipe nor cigarettes (AOR 0.51, 95% Cl 0.30, 0.87).

Conclusions

These results indicate that maternal smoking is associated with termination of breastfeeding, suggesting that structured training should be organized for healthcare professionals, expectant mothers and the general public about the association between maternal smoking and cessation of lactation.

Similar content being viewed by others

Background

Exclusive breastfeeding during the first 6 months and then continued breastfeeding combined with family foods for 2 years or more, for as long as the mother and baby desire, are the most effective ways to ensure a child’s health [1]. However, nearly two in three infants are not exclusively breastfed for the recommended 6 months, a rate that has not improved in the last two decades. Previous reports show that certain sociodemographic characteristics such as maternal age, parity, education, occupation, cultural characteristics and socio-economic status can influence the initiation and duration of exclusive breastfeeding [2,3,4]. Additionally, both maternal smoking and smoke exposure have been reported to influence breastfeeding success rates in different countries [5,6,7,8,9,10].

Harmful effects of smoking on the health of the fetus and neonate, such as low birthweight and prematurity, have been well documented [11, 12]. In addition, maternal smoking during breastfeeding has been characterized by decreased antioxidant properties of breast milk and an altered immune status [13]. Moreover, breast milk content in those who smoke differs in terms of total fat concentration [13, 14], vitamin A, E, and C levels [15] and milk metabolic properties [13]. Infants whose mothers smoked during the lactation period were shown to have a shorter sleeping time [16]. A new study investigating longitudinal effects of environmental tobacco smoke exposure in 37 infants aged 0–24 months suggests that prolonged breastfeeding and reduced smoke exposure may be beneficial for the composition and diversity of gut microbiota [17]. A study with experimental models suggests that smoking exposure during the breastfeeding period can have late effects such as obesity and the associated metabolic syndrome in adulthood [18].

Smoking also affects the sustainability of breastfeeding [19]. A meta-analysis conducted in 2018 detected a relationship between smoking and cessation of breastfeeding [3]. A study of 36,324 infants showed that prenatal maternal tobacco use was related to failure to exclusively breastfeed at about 2 weeks after delivery [20].

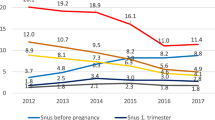

In Turkey, the 2008 Demographic and Health Survey (DHS) showed that 16.5% of lactating women and 11.4% of pregnant women smoked tobacco products [21]. In Spain, in 2018, smoking rates postpartum in 948 women were reported to be 12.5% [2]. The maternal smoking rate in pregnancy was found to be 5.7% in Sydney, Australia, in a study conducted in 2020 [8] and 17.8% in France in 2014, according to INPES (French National Institute for Health Prevention and Education) [49]. According to the Jordan Population and Family Health Survey (JPFHS), the respective rates for cigarette smoking and water pipe use in breastfeeding mothers were 5.8 and 8.4% in 2012, increasing to 9.3 and 10.8% in 2017 [22, 23]. Studies comparing data from different countries show that Jordan has one of the highest national prevalence rates of maternal smoking and second-hand smoking [24,25,26]. Therefore, maternal smoking of both cigarette and water pipe tobacco is a public health problem in Jordan. Smoking has been proposed to influence child health and breastfeeding practices adversely all around the world [2, 27, 28]. To date, the majority of studies on tobacco use have focused on cigarette smoking and have included either hospital-based cases or population with limited sample size [29, 30]. Only one study, a further analysis of the Turkey DHS, evaluated associations between tobacco smoking and breastfeeding at a national level [9]. While experimental studies of effects of water pipe tobacco smoking on breastfeeding exist, no human study investigating the effect of water pipe smoking on lactation was found. In our study, we therefore aimed to investigate the association between use of different tobacco products and current breastfeeding in children under 25 months of age by analyzing data of the 2012 and 2017–18 JPFHS. Our results can provide a basis for infant-friendly initiatives in different countries to heighten awareness among mothers, healthcare providers and the general public of smoking-related effects on breastfeeding, in order increase the prevalence of successful breastfeeding and thereby improve infant health.

Methods

Data sources

The study includes data from two Jordan Population and Family Health Surveys (JPFHS; Jordan DHS), from 2012 and 2017–18. The JPFHS 2012 and 2017–18 were the sixth and seventh of a series of surveys carried out with the support of the Jordanian government, the U.S. Agency for International Development (USAID), the United Nations Children’s Fund (UNICEF) and the United Nations Population Fund (UNFPA). The survey is designed to provide up-to-date information on maternal and child health and nutrition, collecting produce representative data for the country as a whole as well as separate data for the urban and rural areas, for each of the 12 provinces, and for two special domains: the Badia (desert) regions and the populations of refugee camps. Individuals from a total of 13,025 clusters in JPFHS 2012 and 18,286 clusters in JPFHS 2017–18 were interviewed for the survey, the average cluster sizes being 72 and 107 households, respectively. The women’s questionnaire has been analyzed. All women who had ever been married aged 15–49 years who were members of the selected households or who spent the day and night before the survey at that household were eligible for questioning. The total numbers of performed interviews of ever-married women aged 15–49 in JPFHS 2012 and JPFHS 2017-18 were 11,000 and 13,639, respectively [22, 23].

The analysis was restricted to children younger than 25 months born of a singleton birth, who were breastfed, who were the youngest living child of their mother, whose mothers were not in the second or third trimester of pregnancy at the time of questioning, and who were living with their mother. From the 2012 and 2017–18 JPFHS datasets, 3305 and 3421 infants, respectively, were eligible for the study (Fig. 1).

Variables

The following variables were extracted from the data of the JPFHS 2012 and 2017–18: maternal characteristics (region and place of residence, wealth index, maternal age, maternal occupation, maternal education, smoking status), child characteristics [wanted last child (wanted then, wanted later, wanted no more), number of antenatal visits, birth interval, place of delivery, type of delivery, birth order, birth size according to the mother, birthweight, infant age and sex, prelacteal food intake status, current breastfeeding status at time of survey]. The wealth index, a composite measure of a household’s cumulative living standard used in JPFHS surveys, was calculated according to each household’s ownership of selected assets, types of water access and sanitation facilities. The index was characterized as poorest, poorer, middle, richer, or richest.

The key outcome variables were current breastfeeding status and tobacco usage status [water pipe tobacco (hookah or narghile) and/or cigarette tobacco]. The current breastfeeding rate was defined as the proportion of children who had received breast milk during the last 24 h at the time of the survey. In order to evaluate the maternal smoking status, the questions, “Do you currently smoke cigarettes?” and “Do you currently smoke water pipe/hookah/nargila?” were analyzed from the JPFHS questionnaire. Women who replied with “No” in the JPFHS 2012 and “Not at all” in the JPFHS 2017–18 were taken to be “nonsmokers”. The percentages of women who smoked cigarettes or water pipe were calculated both separately and in combination. As maternal smoking was quantified only in the JPFHS 2017–18 survey, only this quantification was used in the analysis.

Statistical analysis

Data analyses were performed using IBM SPSS version 22.0 (IBM Corporation, Armonk, NY, USA). Descriptive statistics were given with unweighted and weighted case numbers and frequencies. For each included parameter, the current breastfeeding rate was analyzed by complex sample binary logistic regression analysis. Then, complex sample multivariate logistic regression analysis was used to evaluate the association of the current breastfeeding rate with maternal smoking status after adjusting for sociodemographic factors (Model 1), birth and postnatal factors (Model 2), and all parameters (Model 3). Distributions of current breastfeeding according to the characteristics were calculated as estimated odds ratios (OR) and 95% confidence intervals (CI).

Ethical considerations

Permission to access data was taken from the DHS Program (DHS Download Account Application 10/10/2020). The data sets were kept confidential.

Results

A total of 6726 suitable mother/infant dyads were included in the study (Table 1). Overall, 53.3% of the infants were boys. The birthweight of 79.8% of the infants was over 2500 g. The current breastfeeding in infants aged 0–6 months was 87%, compared with 19.4% in infants aged 18–24 months. Overall, 4% of mothers were under 20 years of age, 6.8% were over 40 years old. The data indicated that 36.8% of mothers had higher education and 12.7% were in employment. Overall, 4.4% of mothers smoked cigarettes, 5.4% smoked water pipe, and 1.6% smoked both cigarettes and water pipe.

In the JPFHS 2017–18, the number of cigarettes smoked per day was known for 91.4% of mothers who smoked cigarettes; the median number was 10 (3–20 for the 25th to 75th percentiles). In mothers who smoked both cigarettes and water pipe, the daily number smoked was known for 85.0%, the median being 5 (2–20 for the 25th to 75th percentiles).

Of mothers who wanted their last babies when they learnt of their pregnancy (“wanted then”), the proportion who smoked was 48% (OR 0.52, 95% CI 0.31, 0.88), which is lower than in mothers who wanted no more babies. There was no statistically meaningful difference (OR 0.86, 95% CI 0.45, 1.64) in the percentage of smokers between mothers who wanted their babies after learning of their pregnancy (“wanted later”) and mothers who did not.

Factors associated with continued breastfeeding in infants up to 24 months of age in Jordan

The univariate analysis showed no difference in breastfeeding rates between the 2012 and 2017–18 surveys (Table 2). current breastfeeding was found to be more prevalent in the northern region (OR 1.20, 95% Cl 1.04, 1.40) than in the southern region. Women who smoked cigarettes had a lower odds ratio for current breastfeeding (OR 0.60, 95% CI 0.39, 0.92). Mothers having the “poorest” (OR 1.26, 95% Cl 1.03, 1.54) or “poorer” (OR 1.52, 95% Cl 1.21, 1.91) wealth index had higher odds ratios for current breastfeeding than mothers with middle income. The current breastfeeding rate of mothers educated to secondary level was 20% greater compared to mothers with higher education (95% Cl 1.01, 1.43). Women in employment had 41% lower current breastfeeding rates than women who did not work (95% Cl 0.47, 0.75).

Current breastfeeding of infants with a birthweight of over 2500 g was 49% more prevalent compared with those who had a low birthweight (95% Cl 1.23, 1.81). The breastfeeding rate decreased with increasing age of the baby and the lowest current breastfeeding was found in infants aged 18–24 months (OR 0.04, 95% Cl 0.03, 0.05). The current breastfeeding rate for infants given prelacteal food was 20% lower than in those who were not (95% Cl 0.68, 0.94). Infants fed by bottle had a lower odds ratio for current breastfeeding than those not fed by bottle (OR 0.50, 95% Cl 0.42, 0.58). No significant differences in current breastfeeding rate were detected in association with the other factors such as birth order, maternal age, preceding birth interval, antenatal care, place of delivery, birth size, infant sex and “wanted last child status”.

Multivariate analysis of cigarette smoking and water pipe smoking for current breastfeeding up to 24 months of age

When the sociodemographic characteristics were included in multivariate analysis, the year of the JPFHS, region, infant age, maternal tobacoo smoking , the wealth index, and working status of the mothers were associated with current breastfeeding (Table 3). Current breastfeeding in the JPFHS 2017–18 was associated with a 26% lower odds ratio (95% Cl 0.61, 0.90) than the JPFHS 2012. Mothers having the “poorest” (AOR 1.31, 95% Cl 1.00, 1.73) or “poorer” (AOR 1.39, 95% Cl 1.07, 1.81) wealth index had higher odds ratios for current breastfeeding than those with a “middle” wealth index. Among tobacco types, maternal cigarette smoking alone had a lower odds ratio for current breastfeeding compared to use of neither water pipe nor cigarettes (AOR 0.53, 95% Cl 0.32, 0.89). The current breastfeeding of mothers in employment was 52% (95% Cl 0.39, 0.70), a lower rate than that observed for mothers who did not work.

After adjusting for birth and postnatal characteristics, maternal tobacco smoking, preceding birth interval, birth weight, and infant age were associated with current breastfeeding. There was no statistical difference in terms of breastfeeding status between mothers who used and mothers who did not use a water pipe, or mothers who used both cigarettes and water pipe and mothers who used neither. However, maternal use of cigarettes alone showed a lower odds ratio for current breastfeeding compared to nonsmokers (AOR 0.57, 95% Cl 0.33, 0.99). In addition, infants over 2500 g at birth were more likely to be receiving current breastfeeding than infants under 2500 g (AOR 1.45, 95% Cl 1.15, 1.83).

When all factors were included in a multivariate analysis, the year of the JPFHS, maternal tobacco smoking, wealth index, the mother’s working status, birthweight and infant age were associated with current breastfeeding. The AOR of current breastfeeding in the JPFHS 2017–18 was 0.70 (95% Cl 0.54, 0.89) compared to that in the JPFHS 2012. Among tobacco types, only maternal cigarette smoking had a lower odds ratio for current breastfeeding compared with nonsmokers (AOR 0.51, 95% Cl 0.30, 0.87). Mothers having a “poorer” (AOR 1.42, 95% Cl 1.10, 1.83) wealth index had an increased prevalence of current breastfeeding compared with mothers classified with a “middle” wealth index. The current breastfeeding rate of the working mothers was 55% (95% Cl 0.41, 0.75), and thus lower compared with mothers who did not work. Infants over 2500 g at birth had a higher odds ratio than infants who weighed less than 2500 g (AOR 1.49, 95% Cl 1.18, 1.89). Breastfeeding status decreased with increasing age of the infant.

Discussion

In this study, after controlling for sociodemographic features and antenatal characteristics of their infants, breastfeeding amongst mothers who smoked was associated with a 49% lower odds ratio compared with non-smoking mothers. This result is in line with findings of similar studies conducted previously. In a study by Najdawi and Faouri [31] involving 500 mothers in 1995 in Jordan, the percentage of breastfeeding women was 63% for smokers and 90% for nonsmokers in the second month and 43% for smokers and 88% for nonsmokers in the fourth month. Manhire et al.’s study in 2018, with 197 mothers, showed that maternal smoking had a negative influence on breastfeeding duration [27]. Wallenborn and Masho [32] reported that the odds of breastfeeding 8 weeks or less in smokers and nonsmokers were 4.1 and 2.4 times higher in women who had repeat cesarean section compared with women who gave birth vaginally after ceserean section. In a meta-analysis conducted by Cohen et al. in 2018, smoking was the factor most consistently associated with early breastfeeding cessation [3]. Also, a study of women in Erzincan, Turkey, reported that in mothers who did not use tobacco after the birth, the period of exclusive feeding with breast milk was longer compared with mothers who smoked [4].

The reasons why mothers’ smoking habits may adversely affect breastfeeding status have been investigated in a number of studies. Many findings have suggested that smoking reduces the amount of fat in breast milk [14, 33, 34], which in turn disrupts the taste of the breast milk and causes reluctance of the baby to feed [34]. It has also been reported that smoking decreases prolactin (PRL), a hormone that plays an important role in milk production by activating the lipoprotein lipase [34, 35]. Moreover, smoking reduces the amount of breast milk produced [34]. Although these effects have been proposed, the underlying physiological causes have not been fully elucidated. Exposure to tobacco smoke was reported to disturb oxidoreductive balance and influence oxytocin fluctuations during the lactation period in an experimental model in rats [50]. Lactating epithelial cells express alpha-2, alpha-3, beta-2 and beta-4 subtypes of nicotinic acetylcholine receptors [36]. Secretion levels of α- and β-casein and adipophilin (a protein that coats lipid droplets) were found to be significantly decreased in mammary epithelial cells treated with 1.0 μM nicotine. Furthermore, in a culture model, Kobayashi et al. found nicotine to cause apoptosis of mammary epithelial cells via inactivation of the STAT5 and Akt pathways and therefore suggest that nicotine influences milk production in lactating mammary epithelial cells by concurrent inactivation of STAT5 and the glucocorticoid receptor [36]. In a murine model, nicotine was found to exert a direct effect on pituitary PRL-secreting cells, thus inhibiting transcription of the PRL gene [37]. Thus, evidence suggests that postpartum maternal tobacco smoking diminishes milk production, alters the composition and flavor of milk and induces early weaning [38]. Therefore, mothers should be made aware not only of the toxic effects of smoking on the fetus, but also the fact that nicotine use even during pregnancy can have detrimental effects on breast milk production and cause early cessation of breastfeeding [39].

Our data analysis detected no difference concerning the rate of current breastfeeding in mothers who smoked water pipe tobacco. This is in line with Al-Sawalha et al. [40], who reported no change in either the prolactin level or the volume of produced milk in rat dams exposed to water pipe tobacco smoke during lactation. However, several adverse effects were noted in male offspring of the dams, including impairment of long-term memory, a reduction in brain-derived neurotrophic factor, and the induction of oxidative stress in the hippocampus [41]. Previous study reported some changes in milk composition, reduced levels of milk lactose and blood glucose, and increased levels of blood triglycerides, low-density lipoprotein and leptin in lactating dams after exposure to water pipe tobacco smoke [40].

Maternal smoking during pregnancy has harmful consequences, such as low birthweight and colic of the infant and short breastfeeding duration [12]. Moreover, even if smoking is stopped for the duration of pregnancy, postpartum relapse is not uncommon. According to a meta-analysis conducted in 2016, 43% of women who stopped smoking due to pregnancy started smoking again within 6 months after giving birth [42]. Hence, considering the evidentially negative consequences of smoking on breastfeeding and child health during pregnancy and the lactation period, effective interventions should be planned and new studies conducted. In a study investigating effects of smoking restrictions in the USA, it was shown that parents counseled about smoking habits were more likely to reduce tobacco use [43]. Interestingly, despite the negative effects of tobacco on milk production and quality, breastfeeding has been shown to be protective against adverse effects of smoke exposure [44]. In infants who are exposed to tobacco smoke, breastfeeding has still promoted the growth and protected them against infections [45]. Breastfeeding was also found to counteract the effect of passive smoking on the growing respiratory organs and lung function [44].

Strengths and limitations

A strength of the study is that the survey includes two cross-sectional samples from the national studies. However, since it was a cross-sectional study. it was not possible to establish a cause-and-effect relationship. Alongside maternal smoking, second-hand or passive smoke (environmental tobacco smoke) is also known to have detrimental effects on breastfeeding. In addition, smoking could not be quantified due to the limited data of the 2017–18 JPFHS survey. In this study, only maternal usage of cigarette and water pipe tobacco was considered.

It has been observed that the reduction in current breastfeeding prevalence in mothers using cigarette tobacco only was greater than that observed in combined smokers. This might be due to lower cigarette consumption in participants who smoked both types of product. However, since only 1.5% of mothers smoked both cigarettes and water pipe, this finding may be misleading as a result of the limited number of cases.

Smoking mothers from socio-economically disadvantaged backgrounds have been reported to have a higher likelihood of discontinuing exclusive breastfeeding [44, 46, 47]. However, socio-economic status was taken into account in our analyses in the form of a wealth index. Furthermore, we observed that the “wanted last child” status had no effect on current breastfeeding of children under 2 years of age. On the other hand, we have no data about the maternal infant feeding intention which might play a role in sustainability of breastfeeding [48].

Conclusions

The use of cigarettes and water pipes is prevalent among mothers in Jordan. The smoking of cigarettes and water pipes is associated with negative effects on the health of both mother and infant. In this study, we analyzed data from two Jordanian national health reports and we found that cigarette smoking, in particular, was associated with a lower rate of continuation of breastfeeding during the first 2 years of the infant’s life. Taking into account socio-economic and mother-infant factors, a reduction in the likelihood of continuing breastfeeding was related to a low birthweight, increasing age of the infant and maternal smoking. These findings indicate the necessity for counseling and educational interventions that can reduce maternal tobacco use during both pregnancy and lactation in Jordan. Studies investigating smoking in pregnant and breastfeeding mothers and the provision of appropriate consultancy in infant-friendly health institutions can contribute to the promotion of successful breastfeeding. The need remains for further research on effects of tobacco smoking on breastfeeding and effective dissemination of the current knowledge.

Availability of data and materials

The data that support the findings of this study are available from the DHS. However, restrictions apply to the availability of the data, which were used under license for the current study; thus, the data are not publicly available. However, they can be made available from the authors upon reasonable request with the permission of DHS programs.

References

World Health Organization. UNICEF. In: Global Strategy for Infant and Young Child Feeding. Geneva: World Health Organization; 2003.

Lechosa Muniz C, Paz-Zulueta M, Del Rio EC, Sota SM, Saez de Adana M, Perez MM, et al. Impact of maternal smoking on the onset of breastfeeding versus formula feeding: A cross-sectional study. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2019;16(24):4888.

Cohen SS, Alexander DD, Krebs NF, Young BE, Cabana MD, Erdmann P, et al. Factors associated with breastfeeding initiation and continuation: a meta-analysis. J Pediatr. 2018;203:190–196 e21 https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jpeds.2018.08.008.

Salcan S, Topal I, Ates I. The frequency and effective factors of exclusive breastfeeding for the first six months in babies born in Erzincan province in 2016. Eurasian J Med. 2019;51(2):145–9 https://doi.org/10.5152/eurasianjmed.2018.18310.

Lok KYW, Wang MP, Chan VHS, Tarrant M. Effect of secondary cigarette smoke from household members on breastfeeding duration: a prospective cohort study. Breastfeed Med. 2018;13(6):412–7 https://doi.org/10.1089/bfm.2018.0024.

Wu X, Gao X, Sha T, Zeng G, Liu S, Li L, et al. Modifiable individual factors associated with breastfeeding: a cohort study in China. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2019;16(5):820 https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph16050820.

Lechosa-Muniz C, Paz-Zulueta M, Sota SM, de Adana Herrero MS, Del Rio EC, Llorca J, et al. Factors associated with duration of breastfeeding in Spain: a cohort study. Int Breastfeed J. 2020;15(1):79 https://doi.org/10.1186/s13006-020-00324-6.

Chimoriya R, Scott JA, John JR, Bhole S, Hayen A, Kolt GS, et al. Determinants of full breastfeeding at 6 months and any breastfeeding at 12 and 24 months among women in Sydney: findings from the HSHK birth cohort study. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2020;17(15):5384 https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph17155384.

Yalcin SS, Yalcin S, Kurtulus-Yigit E. Determinants of continued breastfeeding beyond 12 months in Turkey: secondary data analysis of the demographic and health survey. Turk J Pediatr. 2014;56(6):581–91.

Nordhagen LS, Kreyberg I, Bains KES, Carlsen KH, Glavin K, Skjerven HO, et al. Maternal use of nicotine products and breastfeeding 3 months postpartum. Acta Paediatr. 2020;109(12):2594–603 https://doi.org/10.1111/apa.15299.

Al-Sheyab NA, Al-Fuqha RA, Kheirallah KA, Khabour OF, Alzoubi KH. Anthropometric measurements of newborns of women who smoke waterpipe during pregnancy: a comparative retrospective design. Inhal Toxicol. 2016;28(13):629–35 https://doi.org/10.1080/08958378.2016.1244227.

Olives JP, Elias-Billon I, Barnier-Ripet D, Hospital V. Negative influence of maternal smoking during pregnancy on infant outcomes. Arch Pediatr. 2020;27(4):189–95 https://doi.org/10.1016/j.arcped.2020.03.009.

Macchi M, Bambini L, Franceschini S, Alexa ID, Agostoni C. The effect of tobacco smoking during pregnancy and breastfeeding on human milk composition-a systematic review. Eur J Clin Nutr. 2020; https://doi.org/10.1038/s41430-020-00784-3.

Burianova I, Bronsky J, Pavlikova M, Janota J, Maly J. Maternal body mass index, parity and smoking are associated with human milk macronutrient content after preterm delivery. Early Hum Dev. 2019;137(104832):104832 https://doi.org/10.1016/j.earlhumdev.2019.104832.

Yilmaz G, Isik Agras P, Hizli S, Karacan C, Besler HT, Yurdakok K, et al. The effect of passive smoking and breast feeding on serum antioxidant vitamin (a, C, E) levels in infants. Acta Paediatr. 2009;98(3):531–6 https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1651-2227.2008.01084.x.

Primo CC, Ruela PB, Brotto LD, Garcia TR, Lima EF. Effects of maternal nicotine on breastfeeding infants. Rev Paul Pediatr. 2013;31(3):392–7 https://doi.org/10.1590/S0103-05822013000300018.

Xie T, Wang Y, Zou Z, He J, Yu Y, Liu Y, et al. Environmental tobacco smoke exposure and breastfeeding duration influence the composition and dynamics of gut microbiota in young children aged 0-2 years. Biol Res Nurs. 2020:1099800420975129 https://doi.org/10.1177/1099800420975129.

Miranda RA, Gaspar de Moura E, Lisboa PC. Tobacco smoking during breastfeeding increases the risk of developing metabolic syndrome in adulthood: Lessons from experimental models. Food Chem Toxicol. 2020;144(111623):29.

Patil DS, Pundir P, Dhyani VS, Krishnan JB, Parsekar SS, D'Souza SM, et al. A mixed-methods systematic review on barriers to exclusive breastfeeding. Nutr Health. 2020;26(4):323–46 https://doi.org/10.1177/0260106020942967.

Letson GW, Rosenberg KD, Wu L. Association between smoking during pregnancy and breastfeeding at about 2 weeks of age. J Hum Lact. 2002;18(4):368–72 https://doi.org/10.1177/089033402237910.

Hacettepe University Institute of Population Studies. Turkey Demographic and Health Survey 2008. Hacettepe University Institute of Population Studies, Ministry of Health General Directorate of Mother and Child Health and Family Planning, T.R. Prime Ministry Undersecratary of State Planning Organization and TÜBİTAK, Ankara, Turkey, 2009.

Department of Statistics and ICF. Jordan Population and Family and Health Survey 2017–18. Amman, Jordan, and Rockville, Maryland, USA: Department of Statistics and ICF International; 2019.

Department of Statistics and ICF International. Jordan population and family health survey 2012. Calverton, Maryland, USA: Department of Statistics and ICF International; 2013.

UNICEF. The state of the World's children 2019. Children, Food and Nutrition. 2019.

Sreeramareddy CT, Pradhan PM. Prevalence and social determinants of smoking in 15 countries from North Africa, central and Western Asia, Latin America and Caribbean: secondary data analyses of demographic and health surveys. PLoS One. 2015;10(7):e0130104 https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0130104.

Abdulrahim S, Jawad M. Socioeconomic differences in smoking in Jordan, Lebanon, Syria, and Palestine: a cross-sectional analysis of national surveys. PLoS One. 2018;13(1):e0189829 https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0189829.

Manhire KM, Williams SM, Tipene-Leach D, Baddock SA, Abel S, Tangiora A, et al. Predictors of breastfeeding duration in a predominantly Maori population in New Zealand. BMC Pediatr. 2018;18(1):299 https://doi.org/10.1186/s12887-018-1274-9.

Tavoulari E-F, Benetou V, Vlastarakos PV, Psaltopoulou T, Chrousos G, Kreatsas G, et al. Factors affecting breastfeeding duration in Greece: what is important? World J Clin Pediatr. 2016;5(3):349–57 https://doi.org/10.5409/wjcp.v5.i3.349.

Weiser TM, Lin M, Garikapaty V, Feyerharm RW, Bensyl DM, Zhu BP. Association of maternal smoking status with breastfeeding practices: Missouri, 2005. Pediatrics. 2009;124(6):1603–10 https://doi.org/10.1542/peds.2008-2711.

Ladomenou F, Kafatos A, Galanakis E. Risk factors related to intention to breastfeed, early weaning and suboptimal duration of breastfeeding. Acta Paediatr. 2007;96(10):1441–4 https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1651-2227.2007.00472.x.

Najdawi F, Faouri M. Maternal smoking and breastfeeding. East Mediterr Health J. 1999;5(3):450–6.

Wallenborn JT, Masho SW. The interrelationship between repeat cesarean section, smoking status, and breastfeeding duration. Breastfeed Med. 2016;11(9):440–7 https://doi.org/10.1089/bfm.2015.0165.

Baheiraei A, Shamsi A, Khaghani S, Shams S, Chamari M, Boushehri H, et al. The effects of maternal passive smoking on maternal milk lipid. Acta Med Iran. 2014;52(4):280–5.

Napierala M, Mazela J, Merritt TA, Florek E. Tobacco smoking and breastfeeding: effect on the lactation process, breast milk composition and infant development. A critical review. Environ Res. 2016;151:321–38 https://doi.org/10.1016/j.envres.2016.08.002.

Amir LH. Maternal smoking and reduced duration of breastfeeding: a review of possible mechanisms. Early Hum Dev. 2001;64(1):45–67 https://doi.org/10.1016/S0378-3782(01)00170-0.

Kobayashi K, Tsugami Y, Suzuki N, Suzuki T, Nishimura T. Nicotine directly affects milk production in lactating mammary epithelial cells concurrently with inactivation of STAT5 and glucocorticoid receptor in vitro. Toxicol in Vitro. 2020;63:104741 https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tiv.2019.104741.

Coleman DT, Bancroft C. Nicotine acts directly on pituitary GH3 cells to inhibit prolactin promoter activity. J Neuroendocrinol. 1995;7(10):785–9 https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1365-2826.1995.tb00715.x.

Bahadori B, Riediger ND, Farrell SM, Uitz E, Moghadasian MF. Hypothesis: smoking decreases breast feeding duration by suppressing prolactin secretion. Med Hypotheses. 2013;81(4):582–6 https://doi.org/10.1016/j.mehy.2013.07.007.

Memis EY, Yalcin SS. Human milk mycotoxin contamination: smoking exposure and breastfeeding problems. J Matern Fetal Neonatal Med. 2021;34(1):31–40 https://doi.org/10.1080/14767058.2019.1586879.

Al-Sawalha NA, Gaugazeh HT, Alzoubi KH, Khabour OF. Maternal waterpipe tobacco smoke exposure during lactation induces hormonal and biochemical changes in rat dams and offspring. Basic Clin Pharmacol Toxicol. 2021;128(2):315–21 https://doi.org/10.1111/bcpt.13493.

Al-Sawalha NA, Alzoubi KH, Khabour OF, Alyacoub W, Almahmood Y. Effect of waterpipe tobacco smoke exposure during lactation on learning and memory of offspring rats: role of oxidative stress. Life Sci. 2019;227:58–63 https://doi.org/10.1016/j.lfs.2019.04.049.

Jones M, Lewis S, Parrott S, Wormall S, Coleman T. Re-starting smoking in the postpartum period after receiving a smoking cessation intervention: a systematic review. Addiction. 2016;111(6):981–90 https://doi.org/10.1111/add.13309.

McMillen R, Wilson K, Tanski S, Klein JD, Winickoff JP. Adult attitudes and practices regarding smoking restrictions and child tobacco smoke exposure: 2000 to 2015. Pediatrics. 2018;141(Suppl 1):S21–S9 https://doi.org/10.1542/peds.2017-1026F.

Moshammer H, Hutter HP. Breast-feeding protects children from adverse effects of environmental tobacco smoke. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2019;16(3):304 https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph16030304.

Yilmaz G, Hizli S, Karacan C, Yurdakök K, Coşkun T, Dilmen U. Effect of passive smoking on growth and infection rates of breast-fed and non-breast-fed infants. Pediatr Int. 2009;51(3):352–8 https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1442-200X.2008.02757.x.

Tanda R, Chertok IR, Haile ZT, Chavan BB. Factors that modify the association of maternal postpartum smoking and exclusive breastfeeding rates. Breastfeed Med. 2018;13(9):614–21 https://doi.org/10.1089/bfm.2018.0079.

Carswell AL, Ward KD, Vander Weg MW, Scarinci IC, Girsch L, Read M, et al. Prospective associations of breastfeeding and smoking cessation among low-income pregnant women. Matern Child Nutr. 2018;14(4):e12622 https://doi.org/10.1111/mcn.12622.

Donath SM, Amir LH. ALSPAC study team. The relationship between maternal smoking and breastfeeding duration after adjustment for maternal infant feeding intention. Acta Paediatr. 2004;93(11):1514–8 https://doi.org/10.1080/08035250410022125.

Guignard R, Beck F, Wilquin JL, Andler R, Nguyen-Thanh V, Richard JB, et al. La consommation de tabac en France et son évolution : résultats du Baromètre santé 2014 [Evolution of tobacco smoking in France: results from the Health Barometer 2014]. Bull Epidémiol Hebd. 2015;(17-18):281–8 http://www.invs.sante.fr/beh/2015/17-18/2015_17-18_1.html.

Napierala M, Merritt TA, Mazela J, Jablecka K, Miechowicz I, Marszalek A, et al. The effect of tobacco smoke on oxytocin concentrations and selected oxidative stress parameters in plasma during pregnancy and post-partum - an experimental model. Hum Exp Toxicol. 2017;36(2):135–45 https://doi.org/10.1177/0960327116639363.

Acknowledgements

The study was performed as the pediatrics specialty thesis of ECÖ. The authors gratefully acknowledge the assistance of Janet Collins (ICCC Rhein-Main, Frankfurt, Germany) in editing the manuscript.

Funding

The current research received no specific grant from any funding agency, commercial or not-for-profit source. No other entity besides the authors had a role in the design, analysis or writing of the current article.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

SSY performed the conception, the design of the work, the acquisition and the analysis. ECÖ performed the design of the work, creation of tables, and has drafted the work. All authors reviewed and edited the final version of manuscript. The author(s) read and approved the final manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate

The current research did not involve human subjects but relied on the secondary data analysis of a deidentified data set. Ethical standards were upheld in the research process. Necessary permissions and survey data were obtained from the DHS programs.

Consent for publication

NA

Competing interests

Authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/. The Creative Commons Public Domain Dedication waiver (http://creativecommons.org/publicdomain/zero/1.0/) applies to the data made available in this article, unless otherwise stated in a credit line to the data.

About this article

Cite this article

Can Özalp, E., Yalçın, S.S. Is maternal cigarette or water pipe use associated with stopping breastfeeding? Evidence from the Jordan population and family health surveys 2012 and 2017–18. Int Breastfeed J 16, 43 (2021). https://doi.org/10.1186/s13006-021-00387-z

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/s13006-021-00387-z