Abstract

Background

Early and exclusive breastfeeding may improve neonatal survival in low resource settings, but suboptimal breastfeeding still exists in areas with high infant mortality. Prelacteal feeding, the practice of giving a non-breastmilk food as a neonate’s first food, has been associated with suboptimal breastfeeding practices. We examined the association of feeding a non-breastmilk food in the first three days of life (early neonatal food, or ENF) with time from birth to initiation of breastfeeding among 25,286 Bangladeshi mother-neonate pairs, in a secondary analysis of a randomized controlled trial in northwestern rural Bangladesh conducted from 2001–2007.

Methods

Trained interviewers assessed the demographic characteristics during pregnancy. At three months postpartum, the interviewers visited participants again and retrospectively assessed demographic and breastfeeding characteristics surrounding the birth. We assessed the relationship between ENF and time to initiation of breastfeeding in hours in both unadjusted and adjusted linear regression analyses. We also calculated reverse cumulative distribution curves for time to initiation of breastfeeding and analyses were stratified by an infant’s ability to breastfeed normally at birth.

Results

The mean ± SD time from birth to initiation of breastfeeding was 30.6 ± 27.9 hours. Only 2,535 (10.0%) of women reported initiating breastfeeding in the first hour after birth and 10,207 (40.4%) reported initiating breastfeeding in the first 12 hours after birth. In adjusted linear regression analyses, feeding ENF was associated with a significant increase in time, in hours, to breastfeeding initiation both among children not able to breastfeed at birth (37.4; 95% CI 33.3, 41.5) and among children able to breastfeed at birth (13.3; 95% CI 12.7, 14.0).

Conclusions

Feeding ENF was strongly associated with delayed initiation of breastfeeding, even after adjusting for other related factors and stratifying on the neonate’s ability to suckle normally after birth. More research is needed to understand the impact of these findings on optimal breastfeeding in this setting. It is possible that ENF feeding and the ability to breastfeed immediately after birth are interrelated in their respective associations to suboptimal breastfeeding initiation. This study in a large population representative of other populations in rural South Asia, demonstrates significantly longer times to breastfeeding initiation than previously appreciated, with a possible important role of ENF feeding.

Trial registration

The randomized controlled trial on which this analysis is based, “Impact of Maternal Vitamin A or Beta-Carotene Supplementation on Maternal and Infant Mortality in Bangladesh”, was registered with ClinicalTrials.gov as trial number ID GHS-A-00-03-00019-00 and identifier NCT00198822. The identifier was first received September 12, 2005 (retrospectively registered). The first participant was enrolled in August 2001.

Similar content being viewed by others

Background

Breastfeeding has many potential health benefits for infants in low and middle income countries, including reducing risk of infection [1–4], malnutrition and undernutrition [5], and mortality [3, 6, 7]. The World Health Organization (WHO) recommends exclusive breastfeeding (feeding only breast milk and, if necessary, medicine) as the standard practice for newborn infants until six months of age [8]. Early initiation of breastfeeding (within an hour of birth) is also recommended by WHO [9] and delayed initiation has been associated with increased risk of infant mortality [10–14]. However, despite exclusive breastfeeding advocacy efforts and evidence that breastfeeding improves infant outcomes in Bangladesh [15], early and exclusive breastfeeding remains low [16–18]. A comprehensive study found a 47.1% prevalence of early breastfeeding and 64.1% prevalence of exclusive breastfeeding until six months in 2011 in Bangladesh [16]. Additionally, early complementary feeding continues to occur [19, 20].

Cultural practices that encourage the early introduction of non-breastmilk foods, prelacteal feeding, have previously been suggested to be disruptive to the optimal timing of breastfeeding initiation [21–24] and to maintaining exclusive breastfeeding as per WHO recommendations [25, 26]. A unique opportunity to conduct a cross-sectional analysis determining whether early newborn feeding (feeding a non-breastmilk food within the first three days of life) is a risk factor for delaying breastfeeding initiation arose within the context of a large cohort of pregnant women and new mothers enrolled in a prospective randomized trial in northwestern rural Bangladesh [27]. We used a retrospective survey, conducted at three months postpartum, to capture all non-breastmilk foods given to neonates within the first three days of life, a period when most breastfeeding is also initiated. In this context, over 590 community based workers ensured postnatal follow up with mothers, allowing all breastfeeding and ENF data to be collected. In this analysis, we refer to these foods as “early neonatal foods” (ENF) because we are unable, through this survey, to establish with sufficient precision whether a food had been given before the initiation of breastfeeding. The objective of this analysis was to explore possible relationships between ENF and suboptimal breastfeeding initiation.

Methods

Participants and study design

We conducted an analysis of data collected for the JiVitA Project in rural Gaibandha, Bangladesh. The details of this randomized controlled trial, “Impact of Maternal Vitamin A or Beta-Carotene Supplementation on Maternal and Infant Mortality in Bangladesh”, have been published elsewhere [27, 28]. In brief, between 2001 and 2007, pregnant women were enrolled continuously into a cluster randomized, placebo and controlled community trial testing the effects of a weekly supplement of either vitamin A or beta-carotene on maternal mortality in northwestern rural Bangladesh. Each participant was interviewed during early pregnancy and at three months postpartum by trained, community based interviewers. Time to breastfeeding initiation was assessed by asking the mother “How many hours after birth did you start to breastfeed this child?” Feeding ENF was assessed by asking “Was anything other than mother’s breastmilk offered to the child within three days after birth?”

Statistical analysis

We used linear regression models to assess the relationship between ENF feeding and the number of hours after birth that breastfeeding began. Potential confounders were identified a priori from factors identified in the breastfeeding literature and included independent variables describing a best guess gestational age of the neonate at birth (defined below), wealth index (defined on a continuous scale as previously described [29]), maternal and child vitality scores (created for this analysis and described below), child sex, maternal age, child size at birth (as perceived by the mother), primigravid status, maternal literacy, whether a Caesarean section was performed at the birth, the location of the birth, and the type of birth attendant present. Child vitality scores consisted of the presence of any of the following characteristics (perceived and reported by the mother) at birth: small infant size, taking more than 1 minute to start breathing or crying, crying weakly, not moving at all, being blue all over or having blue hands or feet, or having convulsions in the first seven days. Maternal vitality scores consisted of the presence of any of the following self-reported symptoms in the seven days after giving birth: high fever, convulsions, vomiting, or dysentery. Each score was constructed by giving a point to each of the conditions listed above, so that higher scores reflect higher risk health states. Most often, the estimate of gestational age was informed by a precise date of the mother’s last menstrual period, derived from continuous longitudinal pregnancy surveillance and optimized by other available information such as positive urine testing [28]. Regression analyses were stratified by the maternal perception of her child’s ability to suckle normally at birth. The beta-coefficients of regression analyses are interpreted as additional hours to breastfeeding from the average. A beta-coefficient value above 0 indicates a delay in breastfeeding as compared to the average.

Diagnostics were performed to test for collinearity among variables in regression models. Participants were dropped from the analysis if they were missing information for any of the independent variables in the regression analysis. Additionally, we created reverse cumulative distribution curves to describe the time to initiation of breastfeeding by ENF feeding, using the Stata [distplot] module.

A value of p < 0.05 was considered significant. Stata 11 and Stata 14 (College Station, TX) were used for statistical analysis.

Results

There were 37,349 women with live births and children that survived past 12 weeks postpartum. After excluding mother-neonate pairs where the postpartum interview was conducted more than 28 days earlier or 28 days later than the three month postpartum mark (n = 10,366), premature births when women whose children had a best guess gestational age of less than 24 weeks at birth (n = 37), and women missing variables of interest (n = 1,660), a total of 25,286 women were included in the analysis (Fig. 1). Women who were excluded due to a late or early interview were similar to women included with regard to all analytic variables (maternal age, primigravid status, wealth index, maternal literacy, child sex, child size at birth, whether an early newborn food was fed, whether colostrum was fed, whether the child had difficulty suckling at birth, the location of birth, whether the child was delivered by Caesarean section, and the birth attendant type (Additional file 1). Women who were excluded took longer, on average, to begin breastfeeding (39.9 ± 28.2 hours to breastfeeding, compared to 30.6 ± 27.9 hours for women included). The majority of women (n = 22,650, 89.6%) fed their newborn an ENF, and 24,073 women (95.2%) fed colostrum (Table 1). The mean ± SD time to breastfeeding initiation from birth was 30.6 ± 27.9 hours (Table 1); the median (IQR) time to initiation was 24 (6–51) hours. Only 2,535 (10.0%) of women reported initiating breastfeeding in the first hour after birth; 10,207 (40.4%) reported initiating breastfeeding in the first 12 hours after birth. Among mothers feeding ENF, animal milk, honey, and sweetened water were the three most common foods. This was true both for babies able to suckle (34.3% fed milk, 26.2% fed honey, and 25.2% fed sweetened water) and not able to suckle (44.3% fed milk, 19.4% fed honey, and 22.5% fed sweetened water).

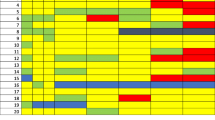

Reverse cumulative distribution curves revealed an increased average time to breastfeeding for all neonates when receiving ENF (Fig. 2). For neonates able to suckle normally at birth, those receiving ENF had a median time to breastfeeding initiation of 13 hours (compared to two hours for those not receiving ENF); for those unable to suckle normally at birth, those receiving ENF had a median time to breastfeeding of 67 hours (compared to seven hours for those not receiving ENF) (Fig. 2). ENF was associated with later initiation of breastfeeding in unadjusted models both among infants not able (36.47 additional hours to breastfeeding initiation; 95% CI 32.40, 40.54) and infants able to breastfeed at birth (14.07 additional hours to breastfeeding initiation; 95% CI 13.43, 14.70) (Table 2). In adjusted models controlling for best guess gestational age, wealth index, maternal and child vitality scores, child sex, maternal age, child size at birth (as perceived by the mother), primigravid status, maternal literacy, whether a Caesarean section was performed at the birth, the location of the birth, and the type of birth attendant present, ENF feeding was still significantly associated with increased time to breastfeeding initiation, both among infants not able (37.36 additional hours to breastfeeding initiation; 95% CI 33.26, 41.46) and infants able to breastfeed normally at birth (13.33 additional hours to breastfeeding initiation; 95% CI 12.69, 13.97) (Table 2).

Discussion

The timing of initiation of breastfeeding within this population was suboptimal, with a mean delay of 30.6 hours between birth and initiation of breastfeeding. Women who fed an ENF initiated breastfeeding significantly later than women who did not feed ENF, even after controlling for other factors likely to hinder breastfeeding initiation and stratifying on the infant’s ability to breastfeed at birth. These results have been shown elsewhere: a recent meta-analysis indicated that early initiation of breastfeeding is low globally [30], and an additional systematic review identified prelacteal feeding as a major barrier to early initiation of breastfeeding in South Asia [31]. Other studies have shown a delay in breastfeeding associated with prelacteal feeding in Ethiopia [23, 32] and western Nepal [33].

In this population, which is demographically representative of rural Bangladesh and similar populations across the greater Gangetic floodplain [27, 28], early neonatal feeding is a common practice [20]. Mothers feeding ENF, and neonates’ inability to breastfeed after birth, are both associated with suboptimal breastfeeding practices. These factors may be interrelated in their respective associations with delayed breastfeeding initiation. For example, neonates who have trouble breastfeeding after birth or who are perceived to be too weak to breastfeed may be given a non-breastmilk food.

This study has at least four limitations. First, the information used in this analysis was derived from interviews performed both during pregnancy and at three months postpartum, and there is a possibility of recall bias. A three month recall bias has been shown to exist in reporting of breastfeeding behaviors [34]. However, this study focused on sensitivity and specificity of self-reported exclusive breastfeeding. The study results indicate that recall bias may overestimate optimal breastfeeding behaviors. Such a bias would reinforce the findings of this study. However, the interviews contained closed ended questions and were conducted by trained interviewers. To limit the possibility of recall bias, we excluded interviews carried out more than 28 days after or fewer than 28 days before the scheduled three month postpartum visit. Excluding interviews where the interview dates were closer to the dates of birth may have removed a subsection of interviews less subject to recall bias, however, this was done in the interest of maintaining internal validity. Women with interview dates similar to each other may be the most likely to give internally consistent interviews. There is a possibility that there may be differential misclassification of the exposure of interest (ENF feeding), based on recall bias about infant difficulty suckling (i.e., women who recall more difficulty suckling also are more apt to remember feeding ENF). However, we believe this possibility to be small due to the high prevalence of ENF feeding throughout the study population. Second, due to the timing of the study interview and the fact that mothers were not asked why they fed ENF, it is impossible to establish the direction of causality in the relationship between delayed initiation of breastfeeding and ENF feeding. Third, the participant interviews used in this analysis were conducted from 2001–2007, and may not describe more recent trends in early newborn feeding and early initiation of breastfeeding.

Finally, given the very large sample sizes of this analysis, we are powered to detect even small differences in the time to initiation of breastfeeding, including those that may be less clinically relevant. However, because of the ubiquity of ENF behaviors across populations in South Asia, rarely have studies been able to compare the attributes of ENF feeding with a very large group of individuals who did not provide their newborn ENFs. This statistical power provides a unique opportunity to identify both major and minor risk factors for delayed initiation of breastfeeding in this context, and allows us to be more confident about the lack of type II error in our statistical analysis.

Conclusions

Our results indicate that ENF and neonatal difficulty of breastfeeding normally are both associated with delayed initiation of breastfeeding. Further research is needed to describe the causal relationship between ENF and delayed breastfeeding; the association shown does not establish whether ENF causes delayed breastfeeding, or whether delayed breastfeeding results in ENF being fed. A closely monitored prospective study may be better able to quantify the causal direction of this relationship. Further research is also needed to better characterize whether ENFs have consequences on neonatal health and survival, and whether exposure to ENF may introduce or expose vulnerable neonates to harmful pathogens or toxins. Any future research on early newborn feeding will be strengthened by a description of the sociocultural context in which ENF occurs for that particular study. It is, however, clear that this important association deserves careful scrutiny before ENFs are discounted as ‘harmless’ traditional practices.

Abbreviations

- ENF:

-

Early newborn feeding

- WHO:

-

World Health Organization

References

Mirhshahi S, Ichikawa N, Shuaib M, Oddy W, Ampon R, Dibley MJ, Kabir AK, Peat JK. Prevalence of exclusive breastfeeding in Bangladesh and its association with diarrhoea and acute respiratory infection: results of the multiple indicator cluster survey 2003. J Health Popul Nutr. 2007;25(2):195–204.

Black RE, Morris SS, Bryce J. Where and why are 10 million children dying every year? Lancet. 2003;361(9376):2226–34.

WHO. Effect of breastfeeding on infant and child mortality due to infectious diseases in less developed countries: a pooled analysis. WHO Collaborative Study Team on the Role of Breastfeeding on the Prevention of Infant Mortality. Lancet. 2000;355(9202):451–455.

WHO. Short-term effects of breastfeeding: a systematic review on the benefits of breastfeeding on diarrhoea and pneumonia mortality. World Health Organization: Geneva, Switzerland; 2013.

UNICEF Innocenti Research Centre. Celebrating the Innocenti Declaration on the protection, promotion and support of breastfeeding. UNICEF Innocenti Research Centre: Florence; 2006.

Pan American Health Organization (PAHO). Quantifying the benefits of breastfeeding: a summary of the evidence. Washington, D.C.: Pan American Health Organization (PAHO); 2002.

Jones G, Steketee RW, Black RE, Bhutta ZA, Morris SS, Bellagio Child Survival Study Group. How many child deaths can we prevent this year? Lancet. 2003;362:65–71.

WHO. Global strategy for infant and young child feeding. World Health Organization: Geneva, Switzerland; 2003.

WHO. Baby-friendly hospital initiative: revised, updated and expanded for integrated care. Section 3, Breastfeeding promotion and support in a baby-friendly hospital: a 20-hour course for maternity staff. World Health Organization and UNICEF: Geneva; 2009.

Mullany LC, Katz J, Li YM, Khatry SK, LeClerq SC, Darmstadt GL, Tielsch JM. Breast-feeding patterns, time to initiation, and mortality risk among newborns in southern Nepal. J Nutr. 2008;138:599–603.

Garcia CR, Mullany LC, Rahmathullah L, Katz J, Thulasiraj RD, Sheeladevi S, Coles CL, Tielsch JM. Breast-feeding initiation time and neonatal mortality risk among newborns in South India. J Perinatol. 2011;31(6):397–403.

Edmond KM, Zandoh C, Quigley MA, Amenga-Etego S, Owusu-Agyei S, Kirkwood BR. Delayed breastfeeding initiation increases risk of neonatal mortality. Pediatrics. 2006;117(3):e380–6.

Abdullah A, Hort K, Butu Y, Simpson L. Risk factors associated with neonatal deaths: a matched case-control study in Indonesia. Glob Health Action. 2016;9:30445.

Debes AK, Kohli A, Walker N, Edmond K, Mullany LC. Time to initiation of breastfeeding and neonatal mortality and morbidity: a systematic review. BMC Public Health. 2013;13 Suppl 3:S19.

Arifeen S, Black RE, Antelman G, Baqui A, Caulfield L, Becker S. Exclusive breastfeeding reduces acute respiratory infection and diarrhea deaths among infants in Dhaka slums. Pediatrics. 2001;108(4):e67.

Hanif HM. Trends in infant and young child feeding practices in Bangladesh, 1993–2011. Int Breastfeed J. 2013;8:10.

Arifeen SE. Child health and mortality. J Health Popul Nutr. 2008;26(3):273–9.

Joshi PC, Angdembe MR, Das SK, Ahmed S, Faruque AS, Ahmed T. Prevalence of exclusive breastfeeding and associated factors among mothers in rural Bangladesh: a cross-sectional study. Int Breastfeed J. 2014;9:7.

Saleh F, Ara F, Hoque MA, Alam MS. Complementary feeding practices among mothers in selected slums of Dhaka City: a descriptive study. J Health Popul Nutr. 2014;32(1):89–96.

Sundaram ME, Labrique AB, Mehra S, Ali H, Shamim AA, Klemm RD, West Jr KP, Christian P. Early neonatal feeding is common and associated with subsequent breastfeeding behavior in rural Bangladesh. J Nutr. 2013;143(7):1161–7.

Hossain MM, Radwan MM, Arafa SA, Habib M, DuPont HL. Prelacteal infant feeding practices in rural Egypt. J Trop Pediatr. 1992;38(6):317–22.

Ahmed FU, Rahman ME, Alam MS. Prelacteal feeding: influencing factors and relation to establishment of lactation. Bangladesh Med Res Counc Bull. 1996;22(2):60–4.

Belachew AB, Kahsay AB, Abebe YG. Individual and community-level factors associated with introduction of prelacteal feeding in Ethiopia. Arch Public Health. 2016;74:6.

NEOVITA Study Group. Timing of initiation, patterns of breastfeeding, and infant survival: prospective analysis of pooled data from three randomised trials. Lancet Glob Health. 2016;4:e266–75.

Pérez-Escamilla R, Segura-Millán S, Canahuati J, Allen H. Prelacteal feeds are negatively associated with breast-feeding outcomes in Honduras. J Nutr. 1996;126:2765–73.

Patil CL, Turab A, Ambikapathi R, Nesamvuni C, Chandyo RK, Bose A, Islam MM, Ahmed AM, Olortegui MP, de Moraes ML, et al. Early interruption of exclusive breastfeeding: results from the eight-country MAL-ED study. J Health Popul Nutr. 2015;34:10.

West Jr KP, Christian P, Labrique AB, Rashid M, Shamim AA, Klemm RD, Massie AB, Mehra S, Schulze KJ, Ali H, et al. Effects of vitamin A or beta carotene supplementation on pregnancy-related mortality and infant mortality in rural Bangladesh: a cluster randomized trial. JAMA. 2011;305(19):1986–95.

Labrique AB, Christian P, Klemm RDW, Rashid M, Shamim AA, Massie A, Schulze K, Hackman AKP, West J. A cluster-randomized, placebo-controlled, maternal vitamin A or beta-carotene supplementation trial in Bangladesh: design and methods. Trials. 2011;12:102.

Gunnsteinsson S, Labrique AB, West Jr KP, Christian P, Mehra S, Shamim AA, Rashid M, Katz J, Klemm RD. Constructing indices of rural living standards in Northwestern Bangladesh. J Health Popul Nutr. 2010;28(5):509–19.

Victora CG, Bahl R, Barros AJD, França GVA, Horton S, Krasevec J, Murch S, Sankar MJ, Walker N, Rollins NC. Breastfeeding in the 21st century: epidemiology, mechanisms, and lifelong effect. Lancet. 2016;387:475–90.

Sharma IK, Byrne A. Early initiation of breastfeeding: a systematic literature review of factors and barriers in South Asia. Int Breastfeed J. 2016;11:17.

Hailemariam TW, Adeba E, Sufa A. Predictors of early breastfeeding initiation among mothers of children under 24 months of age in rural part of West Ethiopia. BMC Public Health. 2015;15:1076.

Khanal V, Scott JA, Lee AH, Karkee R, Binns CW. Factors associated with early Initiation of breastfeeding in western Nepal. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2015;12(8):9562–74.

Bland RM, Rollins NC, Solarsh G, Broeck JV, Coovadia HM. Maternal recall of exclusive breast feeding duration. Arch Dis Child. 2003;88:778–83.

Acknowledgments

The authors gratefully acknowledge Dr. Luke Mullany for scientific input and guidance, and Dr. Rina Rani Paul, Dr. Rebecca Day-Merrill, and Nusrat Jahan for support on the interpretation of study results. The authors are also grateful for the guidance and support for statistical analysis from Alamgir Kabir, Lee Wu, Allan Massie, and Maithilee Mitra. Valuable technical assistance was provided by Rezwanul Haque, Azaduzzaman, and Abdul Jabbar.

Funding

This trial was conducted by the Center for Human Nutrition, Department of International Health, Bloomberg School of Public Health, Johns Hopkins University, under Global Research Activity Cooperative Agreement GHS-A-00- 03-00019-00 between Johns Hopkins University and the Office of Health, Infectious Diseases and Nutrition; the US Agency for International Development (Washington, DC); and Bill and Melinda Gates Foundation (Seattle, WA) Grant 614 (Global Control of Micronutrient Deficiency). Additional support was provided by Sight and Life (Basel, Switzerland), the Sight and Life Research Institute (Baltimore, MD), Nutrilite Health Institute (Nutrilite Division, Access Business Group, LLC, Buena Park, CA), the Canadian International Development Agency, and the National Integrated Population and Health Program of the Ministry of Health and Family Welfare of the Government of the People’s Republic of Bangladesh. The work to produce this manuscript was unfunded.

Availability of data and materials

The authors regret it is not possible to publicly share the dataset used for this analysis due to concerns about patient identifiability. Please contact corresponding author for data requests.

Authors’ contributions

ABL designed the research and ABL. and M.E.S. designed the statistical analysis; ABL, SM, PC, RDWK, KPW, HA, AAS, BU, MR, and SS had a role in carrying out the parent study. MES. wrote the manuscript with input from ABL, SM, PC, RDWK, KPW, HA, AAS, BU, MR, and SS MES. has primary responsibility for final content. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Ethics approval and consent to participate

The protocol for the JiVitA-1 trial was reviewed and approved by the Institutional Review Board at the Bloomberg School of Public Health at Johns Hopkins University, and the Bangladesh Medical Research Council, an autonomous body under the Ministry of Health and Family Welfare, Government of Bangladesh. All participants gave consent to participate before being enrolled in the original randomized controlled trial.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Additional file

Additional file 1: Table S1.

Characteristics of women included and excluded in this analysis. (DOCX 91 kb)

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/), which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made. The Creative Commons Public Domain Dedication waiver (http://creativecommons.org/publicdomain/zero/1.0/) applies to the data made available in this article, unless otherwise stated.

About this article

Cite this article

Sundaram, M.E., Ali, H., Mehra, S. et al. Early newborn ritual foods correlate with delayed breastfeeding initiation in rural Bangladesh. Int Breastfeed J 11, 31 (2016). https://doi.org/10.1186/s13006-016-0090-9

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/s13006-016-0090-9