Abstract

Background

Many communities in developing countries rely on ecosystem services (ESs) associated with wild and cultivated plant species. Plant resources provide numerous ESs and goods that support human well-being and survival. The aim of this study was to identify and characterize wild and tended plant species, and also investigate how local communities in the Eastern Cape Province in South Africa perceive ESs associated with plant resources.

Methods

The study was conducted in six local municipalities in the Eastern Cape Province, between March 2016 and September 2021. Data on socio-economic characteristics of the participants, useful plants harvested from the wild and managed in home gardens were documented by means of questionnaires, observation and guided field walks with 196 participants. The ESs were identified using a free listing technique.

Results

A total of 163 plant species were recorded which provided 26 cultural, regulating and provisioning ESs. Provisioning ESs were the most cited with at least 25 plant species contributing towards generation of cash income, food, traditional and ethnoveterinary medicines. Important species recorded in this study with relative frequency of citation (RFC) values > 0.3 included Alepidea amatymbica, Allium cepa, Aloe ferox, Artemisia afra, Brassica oleracea, Capsicum annuum, Cucurbita moschata, Hypoxis hemerocallidea, Opuntia ficus-indica, Spinacia oleracea, Vachellia karroo and Zea mays.

Conclusion

Results of this study highlight the importance of plant resources to the well-being of local communities in the Eastern Cape within the context of provision of essential direct and indirect ESs such as food, medicinal products, construction materials, fodder, regulating, supporting and cultural services. The ESs are the basis for subsistence livelihoods in rural areas, particularly in developing countries such as South Africa. Therefore, such body of knowledge can be used as baseline data for provision of local support for natural resource management initiatives in the province and other areas of the country.

Similar content being viewed by others

Background

A growing body of literature suggests that local communities in developing countries still continue to rely heavily on provisioning ecosystem services (ESs) derived from plants around their homesteads for their basic necessities [1,2,3,4,5,6]. Research by Bidak et al. [2] showed that plant resources provide direct ESs such as serving as sources of food, medicines, energy and shelter. There are also indirect social and economic ESs derived from plant resources. Ecosystem services are classified into four categories: provisioning ESs such non-timber forest products, fibre, firewood, water, fish and natural medicines; regulating ESs such as pollination, natural hazards, water, air quality, runoff, disease and climate regulation; cultural services that provide recreational, aesthetic and spiritual benefits; and supporting ESs such as habitat for species, soil formation, photosynthesis and nutrient cycling [7]. Plant resources supply all three major categories of ESs, that is, provisioning, regulating and cultural services, including the supporting services that enable agricultural landscapes to be productive [8, 9]. Plant resources provide ESs that extend beyond the provision of food, medicines, energy, shelter and some of these ESs are indirect, unmanaged, underappreciated and undervalued. For example, research by Ladino et al. [10] showed that the plant group Bromeliads provide direct benefits to the human society, and they also form microecosystems in which accumulated water and nutrients support the communities of aquatic and terrestrial species. Previous research by Calvet-Mir et al. [8] and Camps-Calvet et al. [9] showed that plants grown and managed in home gardens are important for the provision of cultural ESs. The authors argued that plant resources managed in home gardens offer nature-based solutions to environmental problems, protection and restoration of agricultural landscapes, promotion of healthy lifestyles, social integration and environmental justice. Similarly, Barrios et al. [11] argued that tree-mediated ESs are recognized as key features of more sustainable agroecosystems but the strategic management of tree attributes for ES provision is poorly understood. For example, Barrios et al. [11] opined that managing trees for ESs requires understanding tree identities, their characteristics, uses and how to manage these trees in the provision of all four ESs categories in different socio-ecological contexts. Despite their importance and everyday use, comprehensive knowledge of the ecology and socio-economic value of ESs derived from plant resources is largely lacking, hindering the ability to monitor, regulate and manage them. Therefore, a clear understanding about the condition of provisioning, regulating, cultural and supporting services provided by plant resources is necessary and such information is derived from both the resource use patterns of the people who are most reliant on these services, as well as the utility of the plant resources exploited by local communities.

Mensah et al. [3] argued that ESs underpin human livelihoods around the world as the use of ESs is important for decision-making processes that target the social expectations of local communities. However, a detailed understanding of the complex variation in the use and relative importance of ESs at the household level is required to fully understand how ESs affect livelihoods across different landscapes [12,13,14,15]. Other researchers are of the view that determination and identification of ESs is a prerequisite in order to estimate the relative importance of ESs in a community and ensuring their conservation and sustainable management [16,17,18]. Therefore, understanding the linkages between ESs and benefits for people is critical for safeguarding natural resources and particularly those important for groups that are most vulnerable to global change [19, 20]. However, the ability of ESs to inform decision-making has been limited by knowledge gaps about the links between ES supply and the delivery and distribution of benefits [20,21,22,23,24,25]. Despite growing interest in ESs provided by plant biodiversity in different landscapes [26,27,28,29,30], few studies have attempted to systematically describe and evaluate the ESs derived from wild and tended plant species. Current statistics show that most ESs research has focused on higher income countries [31] while growing body of literature shows that there is direct dependence on ESs in low-income countries [32, 33]. Therefore, the aim of this study was to assess ESs supplied by wild and tended plant species in the Eastern Cape Province in South Africa. The specific goals of this paper are: i. to identify and characterize the diversity of wild and tended plant species, and ii. to investigate how local communities in the Eastern Cape Province perceive ESs associated with plant resources.

Materials and methods

Study area

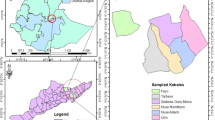

This study was conducted in six local municipalities in the Eastern Cape Province in South Africa, namely Elundini, Mbhashe, Mbizana, Ntabankulu and Raymond Mhlaba and Umzimvubu (Fig. 1). The Eastern Cape Province is the second largest province in the country covering 168 966 km2 of land area [34]. It is regarded as a rural province and is predominantly inhabited by isiXhosa speaking people of Cape Nguni descent. The Eastern Cape Province includes two of the former homeland areas, namely Ciskei and Transkei out of the thirteen former racially-defined homelands or Bantustan areas of South Africa [35]. One of the Apartheid government’s acts of segregation was the Bantu Authorities Act of 1951, which legalized the deportation of Black people into designated homelands. Black people were forcibly removed from urban areas and white farms to those areas demarcated as homelands. The Ciskei and Transkei are today characterized by landlessness, pervasive chronic poverty, low levels of education, economic activity, vulnerability, lack of basic services, a dearth of employment opportunities and high levels of dependency on welfare [36, 37]. An estimated 72% of the population in the Eastern Cape Province live below the poverty line, which is more than the national average of 60% and this is attributed to the legacies of Apartheid, where the Eastern Cape provincial administration inherited the largely impoverished and corrupt former Ciskei and Transkei homelands [38]. Research by Westaway [37] revealed that the majority of households in the Eastern Cape Province spend most of their income on food and there is clear evidence of growing food insecurity as measured by the number of meals consumed and the quantity and variety of foods eaten. Most people in the province live in rural areas, the contribution of agriculture to local livelihoods is low in the entire province and has been in decline for several decades [39]. Research by Shackleton et al. [40] revealed that local people’s livelihoods in the province are centred on grasslands and forests for fodder, wild foods, firewood, medicinal plants and fibre species for weaving.

The six local municipalities are in the Savanna Biome [41] dominated by grassland, succulent thicket and Acacia thornveld, and species such as Aloe aborescens Mill., Aloe ferox Mill., Diospyros dichrophylla (Grand.) De Winter, Eragrostis curvula (Schrad.) Nees, Euphorbia spp., Melinis nerviglumis (Franch.) Zizka, Olea europaea L. ssp. africana (Mill.) P. S. Green and Vachellia karroo (Hayne) Banfi & Glasso. The altitude of the study area is between 0 and 1860 m above sea level, characterized by summer rainfall and dry frosty winters with approximately 500–1069 mm per year [42, 43]. Mean maximum and minimum monthly temperatures are 38 °C in summer and 4 °C in winter, respectively [42,43,44]. The Eastern Cape Province is characterized by a variety of land uses ranging from commercially oriented rangeland stock farming to small-scale vegetable and crop production [42]. Other economic activities in the province include tourism, forestry and wool production [43]. Major crops cultivated in the study area include beetroot (Beta vulgaris L.), cabbage (Brassica oleracea L.), carrots (Daucas carota L.), maize (Zea mays L.), potatoes (Solanum tuberosum L.) and spinach (Spinacia oleracea L.). The majority of the inhabitants (at least 87%) in the study sites are traditional isiXhosa speaking people who are highly dependent on natural resources for their livelihoods [45].

Data collection

This study is part of a wider research on utilization of plant resources and other non-timber forest products in the Eastern Cape Province [46,47,48,49,50,51,52]. Therefore, sampling occurred during one week field excursions conducted between March 2016 and September 2021. Sampling was carried out in six Local Municipalities (Fig. 1). Standardized plant sampling procedures were used to collect specimens [53, 54] involving transect walks in home gardens, farms and the surrounding landscapes. Interview discussions were conducted in the local language, isiXhosa and were translated into English with the help of an interpreter. During the interviews, we documented information on names of plant species, uses, plant parts used and preparation of useful plants. The ESs were identified using a free listing technique [10, 55], whereby interviewees were asked to list benefits and contributions of plant species to human well-being. The stated benefits were matched with the four major categories in the established ES classifications which included provisioning ESs (timber and firewood, edible plants, edible fruits and medicinal plants), regulating ESs (benefits from natural and ecological processes, e.g. pest control, pollination), supporting ES (healthy soil) and cultural ESs (tourism and recreation) [7, 56]. These categories were expanded or modified based on information obtained during fieldwork, focus group discussions and field observations. Plant species were identified in the field and the taxon names conform to those of Germishuizen et al. [57] and the Plants of the World Online [58]. Unknown plant species were collected, pressed, oven-dried and identified by taxonomists at the Giffen Herbarium (UFH) at the University of Fort Hare and Schonland Herbarium (GRA) at Rhodes University, Grahamstown, South Africa.

Ethnobotanical data were gathered from 196 purposively sampled participants using snowball sampling technique [59,60,61]. The participants were requested to sign University of Fort Hare (MAR011) informed consent form and researchers also adhered to the ethical guidelines of the International Society of Ethnobiology (www.ethnobiology.net). The majority of these participants (55.6%) were males and their age ranged from 18 to 84 years. More than half of the participants (57.7%) were above 50 years, while 34.2% were below 40 years of age. About half of the sample (46.4%) were single, 23.5% were married, 16.8% and 13.3% were widowed and divorced, respectively. Close to half of the sample (44.4%) were educated up to primary level, while 21.9% of the sample were educated up to secondary level, 17.9% and 15.8% of the sample had attained tertiary education or no formal education, respectively. About half of the participants (48.5%) were unemployed, surviving on government social grants and remittances.

Data analysis

The data collected were entered in Microsoft Excel 2016 file and this data were used to determine frequencies and other descriptive statistical patterns. Interview responses from participants were coded and sorted into themes, paying particular attention to inconsistencies and unique statements. The relative frequency of citation (RFC) of reported plant species was determined using the following equation:

This index shows the local importance of each species and is given by the frequency of citation (FC) that is the number of informants mentioning the use of species divided by the total number of informants participating in the study [62, 63]

Results and discussion

Floristic composition

A total of 163 plant species were recorded in the Eastern Cape Province (Table 1), with herbs, shrubs and trees having the most species. Pteridophytes and gymnosperms were represented by a single species each, that is, Cheilanthes hirta Sw. (family Sinopteridaceae) and Podocarpus latifolius (Thunb.) R.Br. ex Mirb. (family Podocarpaceae), respectively. A large number of the plant species (67.5%, n = 110) recorded in this study are from 16 families (Table 2). The other 29 families had less representation, between one and two species each. Plant families with the highest number of species were: Asteraceae (16 species), Poaceae (14), Fabaceae (10 species), Solanaceae (nine species), Amaryllidaceae (eight species), Asphodelaceae (seven species), Apiaceae (six species), Amaranthaceae, Asparagaceae, Cactaceae, Myrtaceae and Rosaceae (five species each), Apocynaceae, Lamiaceae and Myrtaceae (four species each) and Salicaceae (three species) (Table 2). Bennett [64] categorized seven of these plant families, that is, Apiaceae, Fabaceae, Lamiaceae, Malvaceae, Myrtaceae, Poaceae and Solanaceae as vital for human existence. Bennett [64] also argued that diets of most cultures around the world rely substantially on species of Fabaceae and Poaceae families, and the world’s three most important cultivated plants, that is, Oryza sativa L. (rice), Triticum aestivum L. (wheat) and Zea mays L. (maize) are grasses and belong to the Poaceae family. Similarly, Hammer and Khoshbakht [65] argued that Asteraceae, Fabaceae and Poaceae are among the most important families in the world as these families have high numbers of domesticated and semi-domesticated species. Among the recorded genera, those species belonging to Acacia Martius, Aloe L., Asparagus Tourn. ex L., Bulbine Wolf, Helichrysum Mill., Opuntia Mill., Prunus L., Solanum L. and Tulbaghia L. with three species each were the dominant taxa. From the 163 plant species recorded, 96 (58.9%) were indigenous to South Africa while 67 species (41.1%) were exotic (Table 1). Similar results were obtained by Akinnifesi et al. [66] who recorded 40.0% exotic plant species in home gardens of São Luis in Brazil arguing that such exotic species ensures biodiversity and genetic diversity. Other researchers argue that exotic species introduced purposefully offer economic and intrinsic benefits when used as food plants [67,68,69], fuel [67, 70,71,72], herbal medicines [73,74,75], ornamental [76,77,78] and shelter [67, 79, 80]. Similarly, Kahane et al. [81] and Caballero-Serrano et al. [82] argued that indigenous and traditional plant species are usually less attractive to farmers and some commercial exotic species are preferred as these species are easier to grow and more marketable than indigenous and traditional food plants. Evaluation of plant diversity in home gardens of Kerala in India revealed that exotic plants constituted 51.0% of the recorded species [83].

Ecosystem services identification

A total of five cultural services (aesthetic, circumcision ritual, handicrafts, spiritual, social cohesion and integration), nine regulating services (air purification, animal enclosure, erosion control, green manure, insect control, live fencing, shading, windbreak and water purification) and 12 provisioning services (cash income, construction materials, culinary herbs, ethnoveterinary medicines, fibre, firewood, fodder, food, herbal medicines, leaf gel, thatching materials and wine production) were identified through interviews and observations made during field work (Fig. 2). Traditional male circumcision is an important cultural ritual practiced by the Xhosa people in the Eastern Cape Province. Male circumcision is carried out for cultural reasons, as an initiation ritual and a rite of passage or transition from boyhood to manhood [84,85,86]. The foreskin is cut off without anaesthesia and the wound is not stitched but bound in traditional medicines to help in the healing process [84,85,86]. The majority of species recorded in this study provided provisioning services such as herbal medicines (95 species, 58.3%), food (67 species, 41.1%), source of income (41 species, 25.2%), ethnoveterinary medicines (25 species, 15.3%), fodder (15 species, 9.2%), construction materials (12 species, 7.4%), firewood (11 species, 6.7%) and thatching materials (9 species, 5.5%) (Fig. 2). The cultural and regulating services were characterized by lower number of plant species than provisioning services. This result is consistent with previous studies that identified provision of food, medicinal products, construction materials, firewood, fibre and fodder as the most important ESs provided by wild and cultivated plant species [87,88,89,90]. Research by Landreth and Saito [91] showed that ESs derived from plant resources are diverse and subject to environmental, economic and cultural livelihood needs. Other researchers argued that food provisioning is particularly important in rural areas of subsistence economies as this ES is important for the well-being of households [92,93,94]. Similarly, a study by Mensah et al. [3] carried out in the Greater Letaba Municipality in the Mopani District of the Limpopo Province in South Africa revealed the dominance of the provisioning ESs such as edible plants, firewood and timber.

A total of 30 medical conditions were treated using remedies prepared from medicinal plants (Table 1). Wounds, respiratory infections, skin diseases, stomach problems, cancer, diabetes, inflammation, headache and sexually transmitted infections (STI) were treated with the highest number of medicinal plant species (Fig. 3). Research by Ghuman et al. [95] showed that medicinal plants are widely used in South Africa for treating wounds, eczema, ringworm, sores, boils, pimples and infected wounds. Similarly, research by Louw et al. [96] showed that monocotyledonous geophytes and bulbous plants indigenous to South Africa are characterized by valuable pharmacological properties such as the analgesic, anticancer, antimutagenic, immune stimulating, anti-infective, antimalarial, cardiovascular and respiratory system effects. Results of this study showed that the value of medicinal plants in terms of number of species traded in the Eastern Cape Province is significant as 45.9% of the traded species were medicinal species in comparison with 54.1% food plants that were bartered with neighbours or sold in local markets (Table 1). Interviews with participants showed that the value of medicinal plants is not only for primary healthcare, but financial, cultural identity and livelihood security. Moreover, previous research by Van Wyk et al. [97] showed that medicinal plants are an important aspect of the daily lives of many people and an important part of the South African cultural heritage.

The number of species used for regulating services ranged from one to four species. Species such as Aloe ferox Mill., Caesalpinia decapetala (Roth) Alson, Opuntia ficus-indica (L.) Mill. and Phragmites australis (Cav.) Steud. were used to reinforce animal and/or livestock enclosures. Agave americana L., Aloe ferox (Fig. 4), Caesalpinia decapetala and Opuntia ficus-indica were used as live fence, while Acacia mearnsii De Wild., Eucalyptus camaldulensis Dehnh., Eucalyptus grandis W. Hill ex Maiden and Pinus halepensis Mill. were used as windbreak (Table 1). Plant species used for cultural services included Helichrysum species, that is, H. nudifolium (L.) Less., H. odoratissimum (L.) Sweet and H. pedunculatum Hilliard & B.L. Burtt. These three Helichrysum species were used as incense to invoke the goodwill of the ancestors and/or used during ceremonial events. Boophone disticha (L. f.) Herb., Helichrysum nudifolium and Helichrysum pedunculatum were used against circumcision wounds (Table 1). Previous research by Calvet-Mir et al. [8] revealed that cultural services are less developed in the literature on ESs although this category plays a central role in explaining the societal value of plant species to several communities around the world. Plant species characterized by edible fruits, seeds, taproot, tubers and those used as leafy vegetables were bartered with neighbours or sold in local markets, reinforcing social cohesion and integration. It was observed that plants sold in large quantities in local markets were species in high demand such as medicinal plants, fruits and leafy vegetables. Agapanthus africanus Hoffmanns, Agave americana, Catharanthus roseus (L.) G. Don, Opuntia ficus-indica, Phoenix reclinata Jacq., Phytolacca dioica L., Pinus halepensis, Pontederia crassipes Mart., Pontederia cordata L. var. ovalis Solms and Salix babylonica L. were grown or maintained around homesteads as ornamental or for their aesthetic value (Table 1). A similar trend was reported by Ndayizeye et al. [98] where the Twa hunters, gatherers and farmers of Burundi sold forest products such as medicinal plants, ethnoveterinary medicines, fodder, ornamental plants and wild vegetables. Therefore, wild plant species deserve special attention due to their possible role as off-farm sources of income, particularly for communities in remote and marginalized areas with limited sources of livelihoods.

Figure 5 shows different plant parts utilized to provide various ESs. Whole or entire plants were associated with aesthetic plants, air purification, animal enclosures, erosion control, insect repellent, live fence, shading and windbreak (Fig. 5). Tree stems were used as firewood and water purification, while leaves were used as sources of culinary herbs, fibre, green manure, handcraft and leaf gel. Several plant parts were used as sources of herbal and ethnoveterinary medicines, food plants and cash income. However, harvesting of bark, bulbs, rhizomes, roots, stems and whole or entire plants, particularly herbaceous plants for medicinal purposes is not sustainable as such strategies threaten the survival of the same species used as food or to treat or manage human ailments or animal diseases.

Important species recorded in this study with RFC values > 0.3 included Alepidea amatymbica Eckl. & Zeyh., Allium cepa L., Aloe ferox, Artemisia afra Jacq. ex Willd., Brassica oleracea L., Capsicum annuum L., Cucurbita moschata Duchesne ex Poir., Hypoxis hemerocallidea Fisch. Mey. & Ave-Lall., Opuntia ficus-indica, Spinacia oleracea L., Vachellia karroo (Hayne) Banfi & Glasso and Zea mays L. Allium cepa (onion), Brassica oleracea (cabbage), Capsicum annuum (pepper), Cucurbita moschata (butternut), Spinacia oleracea (spinach) and Zea mays (maize) were widely grown as food crops assisting in the provision of necessary nutrients and food security. Alepidea amatymbica and Hypoxis hemerocallidea are categorized as threatened in South Africa [99] due to over-collection as traditional medicines [46]. Other plant species that were recorded in this study that are categorized as threatened in South Africa include Boophone disticha (L. f.) Herb., Bowiea volubilis Harv. ex Hook. f. ssp. volubilis, Clivia miniata Regel, Gunnera perpensa L., Ilex mitis (L.) Radlk. and Prunus africana [88]. It is well recognized that medicinal plants primarily valued for their medicinal properties are intensively harvested and some of them tend to be the most threatened by over-exploitation.

Conclusion

Results of this study indicate that local communities in the Eastern Cape Province in South Africa derive ESs such as traditional medicines, food, raw materials, cultural and regulating benefits from plant species collected from the wild as well as cultivated species. This study showed that provisioning services were perceived as the most important ES in comparison with regulating and cultural services. These results highlight the importance of plant resources to the well-being of local communities in the context of provision of essential direct and indirect ESs such as food, medicinal products, construction materials, fodder, regulating, supporting and cultural services. The ESs are the basis for subsistence livelihoods in rural areas, particularly in developing countries such as South Africa. Therefore, understanding the ESs that can be derived from wild and cultivated plant species is important, as well as the implications of utilization of such natural resources in the context of rural livelihoods and well-being. These ESs place plant resources in a web formed by linkages with different ESs services derived from agricultural landscapes. Therefore, these research findings contribute to the wider body of knowledge on ESs derived from plant species, expanding the understanding of the uses and values of plant resources, the livelihood benefits derived by local communities from plant species, and how these benefits influence local support for natural resource management initiatives in the province and other areas of the country.

Availability of data and materials

Raw data is contained in questionnaire forms and cannot be shared in this form.

References

Ouédraogo I, Nacoulma BMI, Hahn K, Thiombiano A. Assessing ecosystem services based on indigenous knowledge in southeastern Burkina Faso (West Africa). Int J Biodiv Sci Ecosyst Serv Manag. 2014;10:313–21.

Bidak LM, Kamal SA, Halmy MWA, Heneidy SZ. Goods and services provided by native plants in desert ecosystems: Examples from the northwestern coastal desert of Egypt. Global Ecol Cons. 2015;3:433–47.

Mensah S, Veldtman R, Assogbadjo AE, Ham C, Kakaï RG, Seifert T. Ecosystem service importance and use vary with socio-environmental factors: a study from household-surveys in local communities of South Africa. Ecosyst Serv. 2017;23:1–8.

Ahammad R, Stacey N, Sunderland TCH. Use and perceived importance of forest ecosystem services in rural livelihoods of Chittagong Hill Tracts. Bangladesh Ecosyst Serv. 2019;35:87–98.

Thorn JPR, Thornton TF, Helfgott A, Willis KJ. Indigenous uses of wild and tended plant biodiversity maintain ecosystem services in agricultural landscapes of the Terai Plains of Nepal. J Ethnobiol Ethnomed. 2020;16:33.

Kimpouni V, Nzila JDD, Watha-Ndoudy N, Madzella-Mbiemo MI, Mouhamed SY, Kampe J-P: Exploring Local People’s Perception of Ecosystem Services in Djoumouna Periurban Forest, Brazzaville, Congo. Int J Forestry Res 2021, Volume 2021, Article ID 6612649.

MEA (Millennium Ecosystem Assessment): Ecosystems and human well-being: a framework for assessment. Washington DC: Island Press; 2003.

Calvet-Mir L, Gómez-Baggethun E, Reyes-García V. Beyond food production: ecosystem services provided by home gardens: a case study in Vall Fosca, Catalan Pyrenees, Northeastern Spain. Ecol Econ. 2012;74:153–60.

Camps-Calvet M, Langemeyer J, Calvet-Mir L, Gómez-Baggethun E. Ecosystem services provided by urban gardens in Barcelona, Spain: Insights for policy and planning. Environ Sci Policy. 2016;62:14–23.

Ladino G, Ospina-Bautista F, Estévez Varón J, Jerabkova L, Kratina P. Ecosystem services provided by bromeliad plants: a systematic review. Ecol Evol. 2019;9:7360–72.

Barrios E, Valencia V, Jonsson M, Brauman A, Hairiah K, Mortimer PE, Okubo S. Contribution of trees to the conservation of biodiversity and ecosystem services in agricultural landscapes. Int J Biodivers Sci Ecosyst Serv Manag. 2018;14:1–16.

Hartter J. Resource use and ecosystem services in a forest park landscape. Soc Nat Resour. 2010;23:207–23.

Kalaba F, Quinn C, Dougill A. Contribution of forest provisioning ecosystem services to rural livelihoods in the Miombo woodlands of Zambia. Popul Environ. 2013;35:159–82.

Kalaba FK, Quinn CH, Dougill AJ. The role of forest provisioning ecosystem services in coping with household stresses and shocks in Miombo woodlands, Zambia. Ecosyst Serv. 2013;5:143–8.

Lakerveld RP, Lele S, Crane TA, Fortuin KPJ, Springate-Baginski O. The social distribution of provisioning forest ecosystem services: Evidence and insights from Odisha, India. Ecosyst Serv. 2015;14:56–66.

De Groot RS, Alkemade R, Braat L, Hein L, Willemen L. Challenges in integrating the concept of ecosystem services and values in landscape planning, management and decision making. Ecol Complexity. 2010;7:260–72.

Balvanera P, Uriarte M, Almeida-Leñero L, Altesor A, DeClerck F, Gardner T, et al. Ecosystem services research in Latin America: the state of the art. Ecosyst Serv. 2012;2:56–70.

Ferraro PJ, Lawlory K, Mullanz KL, Pattanayak SK. Forest figures: ecosystem services valuation and policy evaluation in developing countries. Rev Environ Econ Policy. 2012;6:20–44.

Howe C, Suich H, van Gardingen P, Rahman A, Mace GM. Elucidating the pathways between climate change, ecosystem services and poverty alleviation. Curr Opin Environ Sustain. 2013;5:102–7.

Grantham R, Lau J, Mills DJ, Cumming GS. Social and temporal dynamics mediate the distribution of ecosystem service benefits from a small-scale fishery. Ecosyst People. 2022;18:15–30.

Bennett EM, Cramer W, Begossi A, Cundill G, Díaz S, Egoh BN, et al. Linking biodiversity, ecosystem services, and human well-being: Three challenges for designing research for sustainability. Curr Opin Environ Sustain. 2015;2015(14):76–85.

Bennett EM, Chaplin-Kramer R. Science for the sustainable use of ecosystem services. F1000Research 2016;5:2622.

Rieb JT, Chaplin-Kramer R, Daily GC, Armsworth PR, Böhning-Gaese K, Bonn A, et al. When, where, and how nature matters for ecosystem services: challenges for the next generation of ecosystem service models. Bioscience. 2017;67:820–33.

Chan KMA, Satterfield T. The maturation of ecosystem services: Social and policy research expands, but whither biophysically informed valuation? People Nat. 2020;2:1–40.

Mandle L, Shields-Estrada A, Chaplin-Kramer R, Mitchell MGE, Bremer LL, Gourevitch JD, et al. Increasing decision relevance of ecosystem service science. Nat Sustain. 2021;4:161–9.

Isaacs R, Tuell J, Fiedler A, Gardiner M, Landis D. Maximizing arthropod-mediated ecosystem services in agricultural landscapes: the role of native plants. Front Ecol Environ. 2009;7:196–203.

Lavorel S, Grigulis K, Lamarque P, Colace MP, Garden D, Girel J, et al. Using plant functional traits to understand the landscape distribution of multiple ecosystem services. J Ecol. 2011;99:135–47.

Quijas S, Jackson LE, Maass M, Raffaelli D, Schmid B, Balvanera P. Plant diversity and generation of ecosystem services at the landscape scale: expert knowledge assessment. J Appl Ecol. 2012;49:929–40.

Suso MJ, Bebeli PJ, Christmann S, Mateus C, Negri V, Pinheiro de Carvalho MAA, Torricelli R, Veloso MM: Enhancing legume ecosystem services through an understanding of plant–pollinator interplay. Front Plant Sci 2016, 7:333.

Faucon MP, Houben D, Lambers H. Plant functional traits: soil and ecosystem services. Trends Plant Sci. 2017;22:385–94.

Lautenbach S, Mupepele A, Dormann CF, Lee H, Schmidt S, Scholte SSK, et al. Blind spots in ecosystem services research and challenges for implementation. Reg Environ Change. 2019;19:2151–72.

Yang W, Dietz T, Liu W, Luo J, Liu J. Going beyond the millennium ecosystem assessment: an index system of human dependence on ecosystem services. PLoS ONE. 2013. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0064581.

Huq N, Pedroso R, Bruns A, Ribbe L, Huq S. Changing dynamics of livelihood dependence on ecosystem services at temporal and spatial scales: an assessment in the southern wetland areas of Bangladesh. Ecol Indic. 2020;110:105855.

Statistics South Africa (STATS SA): Provincial profile: north-west community survey 2016, Statistics South Africa, Pretoria; 2018. Available at: http://www.statssa.gov.za/publications/P0318/P03182018.pdf, accessed on 6 October 2021.

Khapoya V. Bantustans in South Africa: the role of the multinational corporations. J Eastern Afr Res Dev. 1980;10:28–49.

ECSECC (Eastern Cape Socio Economic Consultative Council): Eastern Cape socio-economic atlas 2012: A visual tour of the Eastern Cape physical and social terrain; 2012. http://www.ecsecc.org. Accessed on 6 October 2021.

Westaway A. Rural poverty in the Eastern Cape Province: Legacy of apartheid or consequence of contemporary segregation? Dev Southern Afr. 2012;29:115–25.

Thornton A. Pastures of plenty? Land rights and community-based agriculture in Peddie, a former homeland town in South Africa. Appl Geogr. 2009;29:12–20.

Hebinck P, Lent P. Livelihoods and landscape: the people of Guquka and Koloni and their resources. Leiden/Boston: Brill Academic Publishers; 2007.

Shackleton CM, Timmermans HG, Nongwe N, Hamer N, Palmer RCG. Direst-use value of non-timber forest products from two areas on the Transkei Wild Coast. Agrekon. 2007;46:135–55.

Mucina L, Rutherford MC: The Vegetation of South Africa, Lesotho and Swaziland. Strelizia 19. Pretoria: South African National Biodiversity Institute; 2006.

Jari B, Fraser GCG. Influence of institutional and technical factors on market choices of smallholder farmers in the Kat River Valley. In: van Schalkwyk HD, Groenewald JA, Fraser GCG, Obi A, van Tilburg A, editors. Unlocking markets to smallholders: lessons from South Africa. Wageningen: Wageningen Academic Press; 2012. p. 59–89.

Manyevere A, Muchaonyerwa P, Laker MC, Mnkeni PNS. Farmers’ perspectives with regard to crop production: An analysis of Nkonkobe municipality, South Africa. J Agr Rural Dev Trop Subtrop. 2014;115:41–53.

Palmer R, Timmermans H, Fay D. From conflict to negotiation: nature-based development on South Africa’s Wild Coast. Grahamstown: Human Science Research Council; 2000.

Hamann M, Tuinder V. Introducing the Eastern Cape: a quick guide to its history, diversity and future challenges. Stockholm: Stockholm Resilience Centre, Stockholm University; 2012.

Maroyi A. Diversity of use and local knowledge of wild and cultivated plants in the Eastern Cape province, South Africa. J Ethnobiol Ethnomed. 2017;13:43.

Atyosi Z, Ramarumo LJ, Maroyi A. Alien plants in the Eastern Cape province in South Africa: perceptions of their contributions to livelihoods of local communities. Sustainability. 2019;11:5043.

Thinyane Z, Maroyi A. Non-timber forest products (NTFPs): A viable option for livelihood enhancement in the Eastern Cape province, South Africa. Biol Sci. 2019;19:248–58.

Thinyane Z, Maroyi A. Medicinal plants used by the inhabitants of Alfred Nzo District Municipality in the Eastern Cape province, South Africa. J Pharm Nutr Sci. 2019;9:157–66.

Maroyi A. Ethnobotanical study of wild and cultivated vegetables in the Eastern Cape province, South Africa. Biodiversitas. 2020;21:3982–9.

Maroyi A. Diversity of edible plants in home gardens of the Eastern Cape Province, South Africa. Ecol Environ Cons. 2021;27:378–85.

Ngcaba P, Maroyi A. Home gardens in the Eastern Cape province, South Africa: a promising approach to enhance household food security and well-being. Biodiversitas. 2021;22:4045–53.

Bridson D, Foreman . The herbarium handbook; Kew, Royal Botanic Gardens: Richmond, UK; 1998.

Victor JE, Koekemoer M, Fish L, Smithies SJ, Mössmer M. Herbarium essentials: The southern African herbarium user manual. National Botanical Institute: Pretoria, South Africa; 2004.

Bieling C, Plieninger T, Pirker H, Vogl CR. Linkages between landscapes and human well-being: An empirical exploration with short interviews. Ecol Econ. 2014;105:19–30.

de Groot RS, Wilson MA, Boumans RMJ. A typology for the classification, description and valuation of ecosystem functions, goods and services. Ecol Econ. 2002;41:393–408.

Germishuizen G, Meyer NL, Steenkamp Y, Keith M. A checklist of South African plants. Pretoria: Southern African Botanical Diversity Network Report (SABONET) No. 41; 2003.

POWO: Plants of the World Online. Facilitated by the Royal Botanic Gardens, Kew; 2021. Available at: http://www.plantsoftheworldonline.org/, accessed on 3 November 2021.

Heckathorn DD. Snowball versus respondent-driven sampling. Sociol Methodol. 2011;41:355–66.

Etikan I, Alkassim R, Abubakar S. Comparison of snowball sampling and sequential sampling technique. Biometric Biostat Int J. 2015;3:1–2.

Waters J. Snowball sampling: a cautionary tale involving a study of older drug users. Int J Soc Res Methodol. 2015;18:367–80.

Faruque MO, Uddin SB, Barlow JW, Hu S, Dong S, Cai Q, Li X, Hu X. Quantitative ethnobotany of medicinal plants used by indigenous communities in the Bandarban District of Bangladesh. Front Pharmacol. 2018;9:40.

Ahmad M, Sultana S, Fazl-i-Hadi S, Hadda TB, Rashid S, et al. An ethnobotanical study of medicinal plants in high mountainous region of Chail valley (district Swat-Pakistan). J Ethnobiol Ethnomed. 2014;10:36.

Bennett BC. Twenty-five economically important plant families; 2011. Encyclopedia of Life Support Systems. Available at: http://www.eolss.net/Sample-Chapters/C09/E6-118-03.pdf. Accessed on 15 December 2021.

Hammer K, Khoshbakht K. A domestication assessment of the big five plant families. Genet Resour Crop Evol. 2015;62:665–89.

Akinnifesi FK, Sileshi G, da Costa J, de Moura EG, da Silva RF, Ajayi OC, et al. Floristic composition and canopy structure of home-gardens in São Luís city, Maranhão State, Brazil. J Hortic Forestry. 2010;2:72–86.

Midgley SJ, Pinyopusarerk K, Harwood CE, Doran JC. Exotic plant species in Vietnam’s economy: The contributions of Australian trees. Working Paper 1997/4, Research School of Asia-Pacific Studies, Australian National University, Canberra, Australia; 1996.

Small E. Top 100 exotic food plants. Boca Raton: CRC Press; 2011.

Chamorro MF, Ladio A. Management of native and exotic plant species with edible fruits in a protected area of NW Patagonia. Ethnobiol Cons. 2021. https://doi.org/10.15451/ec2021-02-10.14-1-24.

Dutta S, Hossain MK, Hossain MA, Chowdhury P. Exotic plants and their usage by local communities in the Sitakunda Botanical Garden and Eco-Park, Chittagong. Bangladesh For Res. 2015;4:136.

Shanavas A, Kumar BM. Fuelwood characteristics of tree species in the homegardens of Kerala, India. Agroforest Syst. 2003;58:11–24.

Tabuti JR, Dhillion SS, Lye KA. Firewood use in Bulamgi County, Uganda: species selection, harvesting and consumption patterns. Biomass Bioenergy. 2003;25:581–96.

Maroyi A. Ethnomedicinal uses of exotic plant species in south-central Zimbabwe. Indian J Trad Knowl. 2018;17:71–7.

Semenya SS, Maroyi A. Exotics plants used therapeutically by Bapedi traditional healers for respiratory infections and related symptoms in the Limpopo province, South Africa. Indian J Trad Knowl. 2018;17:663–71.

McGaw LJ, Omokhua-Uyi AG, Finnie JF, Van Staden J. Invasive alien plants and weeds in South Africa: a review of their applications in traditional medicine and potential pharmaceutical properties. J Ethnopharmacol. 2022;283:114564.

Niemiera AX, Von Holle B. Invasive plant species and the ornamental horticulture industry. In Inderjit (Ed.), Management of invasive weeds (pp. 167–187). New York, NY: Springer, USA; 2009.

Humair F, Kueffer C, Siegrist M. Are non-native plants perceived to be more risky? Factors influencing horticulturists’ risk perceptions of ornamental plant species. PLoS ONE. 2014;9:e102121.

Staab M, Pereira-Peixoto MH, Klein A-M. Exotic garden plants partly substitute for native plants as resources for pollinators when native plants become seasonally scarce. Oecologia. 2020;194:465–80.

Mekonen T, Giday M, Kelbessa E. Ethnomedicinal study of home garden plants in Sebeta-Awas District of the Oromia Region of Ethiopia to assess use, species diversity and management practices. J Ethnobiol Ethnomed. 2015;11:64–76.

Tadesse E, Abdulkedir A, Khamzina A, Son Y, Noulekoun F. Contrasting species diversity and values in home gardens and traditional parkland agroforestry systems in Ethiopian sub-humid lowlands. Forests. 2019;10:266.

Kahane R, Hodgkin T, Jaenicke H, Hoogendoorn C, Hermann M, Keatinge JDH, d’Arros Hughes J, Padulosi S, Looney N. Agrobiodiversity for food security, health and income. Agron Sustain Dev. 2013;33:671–93.

Caballero-Serrano V, Onaindia M, Alday JG, Caballero D, Carrasco JC, McLaren B, Amigo J. Plant diversity and ecosystem services in Amazonian homegardens of Ecuador. Agric Ecosyst Environ. 2016;225:116–25.

George MV, Christopher G. Structure, diversity and utilization of plant species in tribal homegardens of Kerala, India. Agroforest Syst. 2020;94:297–307.

Froneman S, Kapp PA. An exploration of the knowledge, attitudes and beliefs of Xhosa men concerning traditional circumcision. Afr J Primary Health Care Fam Med. 2017;9:a1454.

Prusente S, Khuzwayo N, Sikweyiya Y. Exploring factors influencing integration of traditional and medical male circumcision methods at Ingquza Hill Local Municipality, Eastern Cape: A socio-ecological perspective. Afr J Primary Health Care Fam Med. 2019;11:a1948.

Maroyi A. Use of herbal formulations for the treatment of circumcision wounds in Eastern and Southern Africa. Plant Sci Today. 2021;8:517–27.

Sandhu HS, Wratten SD, Cullen R. The role of supporting ecosystem services in conventional and organic arable farmland. Ecol Complexity. 2010;7:302–10.

Sandhu HS, Wratten SD, Cullen R. Organic agriculture and ecosystem services. Environ Sci Policy. 2010;13:1–7.

Swinton SM, Lupi F, Robertson GP, Hamilton SK. Ecosystem services and agriculture: cultivating agricultural ecosystems for diverse benefits. Ecol Econ. 2007;64:245–52.

Cuni-Sanchez A, Imani G, Bulonvu F, Batumike R, Baruka G, Burgess ND, Klein JA, Marchant R. Social perceptions of forest ecosystem services in the Democratic Republic of Congo. Hum Ecol. 2019;47:839–53.

Landreth N, Saito O. An ecosystem services approach to sustainable livelihoods in the homegardens of Kandy, Sri Lanka. Aust Geogr. 2015;45:355–73.

Zaldivar ME, Rocha OJ, Castro E, Barrantes R. Species diversity of edible plants grown in homegardens of Chibchan Amerindians from Costa Rica. Hum Ecol. 2002;30:301–16.

Wu J. Landscape sustainability science: ecosystem services and human well-being in changing landscapes. Landsc Ecol. 2013;28:999–1023.

Reed J, van Vianen J, Foli S, Clendenning J, Yang K, MacDonald M, Petrokofsky G, Padoch C, Sunderland T. Trees for life: the ecosystem service contribution of trees to food production and livelihoods in the tropics. For Policy Econ. 2017;84:62–71.

Ghuman S, Ncube B, Finnie JF, McGaw LJ, Coopoosamy RM, Van Staden J. Antimicrobial activity, phenolic content, and cytotoxicity of medicinal plant extracts used for treating dermatological diseases and wound healing in KwaZulu-Natal, South Africa. Front Pharmacol. 2016;7:320.

Louw CAM, Regnier TJC, Korsten L. Medicinal bulbous plants of South Africa and their traditional relevance in the control of infectious diseases. J Ethnopharmacol. 2002;82:147–54.

Van Wyk B-E, Van Oudtshoorn B, Gericke N. Medicinal plants of South Africa. Pretoria, South Africa: Briza Publications; 2013.

Ndayizeye G, Imani G, Nkengurutse J, Irampagarikiye R, Ndihokubwayo N, Niyongabo F, Cuni-Sanchez A. Ecosystem services from mountain forests: Local communities’ views in Kibira National Park, Burundi. Ecosyst Serv. 2020;45:101171.

Raimondo D, von Staden L, Foden W, Victor JE, Helme NA, Turner RC, Kamundi DA, Manyama PA. Red list of South African plants. Pretoria: Strelitzia 25, South African National Biodiversity Institute, Pretoria;2009.

Acknowledgements

I acknowledge positive criticisms from anonymous reviewers.

Funding

The author would like to express his gratitude to the Water Research Commission (WRC), National Research Foundation (NRF) and Govan Mbeki Research and Development Centre (GMRDC), University of Fort Hare for financial support to conduct this research.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Author conceived the study and wrote the manuscript

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate

This study was approved by the University of Fort Hare’s Research Ethics Committee (UREC) on 25 February 2014, and ethics clearance code is MAR011. Before conducting interviews, all participants signed the prior informed consent form.

Consent for publication

This manuscript does not contain any individual person’s data, and therefore, no further consent is required for publication.

Competing interests

The author declares that he has no conflict of interest.

Additional information

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/. The Creative Commons Public Domain Dedication waiver (http://creativecommons.org/publicdomain/zero/1.0/) applies to the data made available in this article, unless otherwise stated in a credit line to the data.

About this article

Cite this article

Maroyi, A. Traditional uses of wild and tended plants in maintaining ecosystem services in agricultural landscapes of the Eastern Cape Province in South Africa. J Ethnobiology Ethnomedicine 18, 17 (2022). https://doi.org/10.1186/s13002-022-00512-0

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/s13002-022-00512-0