Abstract

Background

The present study documents the ethnomedicinal knowledge among the traditional healers of the Pangkhua indigenous community of Bangladesh. The documented data from this area was quantitatively analyzed for the first time. We aimed to record ethnomedicinal information from both the traditional healers and also the elderly men and women of the community, in order to compile and document all available information concerning plant use and preserve it for the coming generations. We aimed to compare how already known species are used compared to elsewhere and particularly to highlight new ethnomedicinal plant species alongside their therapeutic use(s).

Methods

All ethnomedicinal information was collected following established techniques. Open-ended and semi-structured techniques were primarily utilized. Data was analyzed using different quantitative indices. The level of homogeneity between information provided by different informants was calculated using the Informant Consensus Factor. All recorded plant species are presented in tabular format, alongside corresponding ethnomedicinal usage information.

Results

This investigation revealed the traditional use of 117 plant species, distributed among 104 genera and belonging to 54 families. There was strong agreement among the informants regarding ethnomedicinal uses of plants, with Factor of Informant Consensus (FIC) values ranging from 0.50 to 0.66, with the highest number of species (49) being used for the treatment of digestive system disorders (FIC 0.66). In contrast, the least agreement (FIC = 0.50) between informants regarding therapeutic uses was observed for plants used to treat urinary disorders. The present study was compared with 43 prior ethnomedicinal studies, conducted both nationally and in neighboring countries, and the results revealed that the Jaccard index (JI) ranged from 1.65 to 33.00. The highest degree of similarity (33.00) was found with another study conducted in Bangladesh, while the lowest degree of similarity (1.65) was found with a study conducted in Pakistan. This study recorded 12 new ethnomedicinal plant species, of which 6 have never been studied pharmacologically to date.

Conclusions

This study showed that the Pangkhua community still depends substantially on ethnomedicinal plants for the treatment of various ailments and diseases and that several of these plants are used in novel ways or represented their first instances of use for medicinal applications.

Similar content being viewed by others

Background

Traditional herbal medicine in Bangladesh has strong cultural and religious foundations. It manifests in different ways among indigenous groups in their ritual or ceremonial practices, spiritual practices, and self-healing practices. Indigenous communities have utilized this local knowledge for centuries to cure different diseases. Reportedly, more than 80% of the Bangladeshi use non-allopathic medicines (Ayurveda, Siddha, Unani, and homeopathy) for their healthcare, with herbs constituting a major ingredient of these alternative systems of medicine [1]. Bangladesh is a country that is considered rich in medicinal plant genetic resources, by virtue of its favorable agroclimatic conditions and seasonal diversity. With productive soils and a tropical climate, more than 5000 angiospermic plant species have been recorded in the country [2], of which about 250 have documented use in traditional medicine systems [3]. About 75% of the country’s total population lives in rural areas, and almost 80% is dependent on natural resources (e.g., medicinal plants) for their primary healthcare needs [4]. Rural/indigenous peoples are capable of identifying many species of plants yielding various products, including food, firewood, medicine, forage, and tools for daily needs. With such a high demand for herbal medicines, the medicinal plant sector has been cited as the most promising business sector in Bangladesh [5], with more than 500 companies producing herbal medicines, yet despite the biodiversity described above, more than 90% of the plants and products needed to meet domestic demands are imported from other countries, such as India, Nepal, and Pakistan.

Many indigenous Bangladeshi live in deep forest zones. They include those people living within the three Chittagong Hill Tract districts (CHTs) of south-eastern Bangladesh, within which there are 12 indigenous communities [6]. The smallest of these communities is the Pangkhua, who dwell in the remote Pangkhua paras, an isolated part of the Bilaichari Upazilla of the Rangamati CHT. In the wet season, the only way to reach Pangkhua paras is by motorboat, taking 6 h, while in the dry season it takes more than 8 h on foot. Like other remote communities, the Pangkhua have their own distinct traditional healthcare system and practices. In fact, the nearest conventional medicine facility is in Belaichari Upazilla sadar, the only Government health facility nearby (about 15 km), with basic health facilities. Services there are provided by two medical practitioners alongside three paramedics. The Pangkhua people thus have inadequate access to modern treatments, and in any case, allopathic medicine is largely unaffordable to them. Traditional medicinal knowledge, on the other hand, is orally transmitted from one generation to the next. Typically, every elderly man and woman of the community can prepare herbal formulations for the treatment of common ailments, such as fever, cough, cold, dysentery, diarrhea, and gastritis. Typically, they visit professional healers only when they suffer from more serious symptoms or conditions, such as jaundice, cholera, malaria, or cancers. The headmen (karbari) of each village also act as professional healers. In fact, many Pangkhua believe that they lose their community spirit if they receive allopathic care. Local government has had to enforce modern treatment in instances of contagious disease.

Several studies on ethnomedicinal plants of Bangladesh have been conducted in the past, and comprehensive works have already been published [7,8,9,10,11,12,13]. However, few studies focus on the Rangamati district [10, 14, 15] with almost nothing on the Pangkhua indigenous community. With this in mind, the Pangkhua indigenous community was selected for the present study, as their ethnomedicinal practices have not been thoroughly investigated to date. It was important to ascertain who among them represent the custodians of such knowledge and to document their uses of medicinal plants. To the best of our knowledge, this is the pioneer quantitative documentation of medicinal plants in the studied area.

Methods

Study area

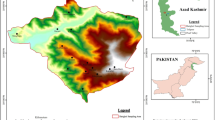

The present study was carried out in the Pangkhua areas of the Belaichhari Upazila within the Rangamati District (Fig. 1). This district is part of the Chittagong division and Chittagong Hill Tracts. Belaichhari thana (now an upazila) was established in 1976. It consists of 3 Union parishads, 9 mouzas and 30 villages. The Belaichhari Upazila is situated approximately between 20° 50′ and 22° 35′ N latitude and between 90° 38′ and 92° 17′ E longitude. The Rainkhiang is the main river of the upazilla. The district lies in the south-east of Bangladesh and has a tropical monsoon climate. There are three main seasons: the dry season (November to March), which is sunny and dry; the pre-monsoon (April to May), which is very hot and sunny with occasional showers; and the rainy season (June to October), which is warm, cloudy, and wet. Temperatures of the Belaichhari Upazila are moderate, with a mean monthly average temperature in Rangamati of 25.8 °C and annual monthly average temperatures ranging from 13.4 to 34.6 °C. The mean annual rainfall is 2865.4 mm, with mean monthly maxima and minima of 679 mm (July) and 7.4 mm (January), respectively [16].

A map of the studied area [16]

Methods of study

The success of ethnobotanical documentation depends on the cooperative relationship between the researcher and local informant. Knowledgeable informants are very important for the study of ethnobotany [17, 18]. Various techniques are recommended for ethnobotanical studies, including (i) direct or participant observation, (ii) checklist interview, (iii) group interview, (iv) field interview, (v) plant interview, and (vi) market survey [19, 20]. All of these techniques were followed in this study except the use of checklist interviews. The interview is a dynamic process involving spoken interactions between two or more people. In general, open-ended and semi-structured techniques were followed. Initial contacts are very important to understand an area and its people. Initial contacts were made with headmen, teachers, and students within the area to select informants. Upon identification of informants, if necessary, interpreters were also appointed. Ethnobotanical information regarding the usage of medicinal plants available in the local area for treating various ailments and diseases was collected through direct interviewing of traditional healers and other informants possessing traditional knowledge about medicinal plants. During the interviews, information was noted using data documentation sheets; in addition, audio recording was performed with a digital voice recorder. Contact in the field was conducted over a total of 43 days, in different seasons, with interviews conducted in the Chittagonian language, accompanied by a local student (Bathue Pankhua) and with consultancy with a local doctor (Dr. Mizanur Rahman).

Quantitative analysis

To analyze the data, we adopted the following quantitative ethnobotanical techniques:

Factor of informant consensus (FIC)

The level of homogeneity between information provided by different informants was calculated using the factor of informant consensus (FIC) [21, 22]. It is calculated as FIC = Nur – Nt/(Nur – 1), where Nur is the number of use reports from informants for a particular plant-use category and Nt is the number of taxa or species associated with that plant-use category across all informants. FIC values range between 0 and 1, with FIC = 1 indicating the highest level of informant consensus. A high value (close to 1) indicates that relatively few taxa (or, more usually, species) are used by a large proportion of informants, while a low value indicates that informants differ on the taxa to be used in treatment within a category of illness. Therefore, if informants use few taxa, then a high degree of consensus is reached and medicinal tradition is thus viewed as well-defined [23].

Jaccard index (JI)

We also wished to calculate similarities between our studies with prior ethnobotanical studies carried out in other parts of Bangladesh, as well as those from neighboring countries. This may be expressed using the Jaccard index (JI), which uses the following formula [24, 25]:

JI = C × 100/A + B − C, where, A is the recorded number of species of the current study area a, B is the documented number of species of another study area b, and C is the number of species common to both areas a and b.

Results

Enumeration of taxa

The ethnobotanical survey was carried out three times during summer and winter seasons from January 2016 to September 2017. All plant materials were collected and identified through expert consultation, by comparison with herbarium specimens and through use of literature references. Following preservation, plant materials were numbered and deposited as voucher specimens in the Chittagong University Herbarium. Descriptions and current nomenclature were compared with the recent “Dictionary of Plant Names of Bangladesh-Vascular Plants” [2] and with www.theplantlist.org. The ethnomedicinal value of each plant was cataloged as follows: botanical name (with voucher number in brackets), Bangla name, Pangkhua name, family, habit, plant part(s) used, disease(s)/illness treated, usage information, and prior documentation in the allied literature (Table 1).

Demography of informants

A total of 218 people, including traditional healers and other community members, mostly the elderly men and women, with ages ranging from 27 to 86 years were interviewed, and of them, the majority (65.6%) belonged to the age group of 51–70. We considered as informants those reporting one or more ethnomedicinal uses of a species (see Additional file 1 as an example). Demographics by gender, age, education, and occupation of participants are summarized in Table 2. Detailed clarification of informants is presented in an additional file (see Additional file 2).

Ethnomedicinal plants and part(s)

The present investigation details 117 species of ethnomedicinal plants distributed across 104 genera and belonging to 54 families (Table 1). The highest numbers of ethnomedicinal plants recorded were from the Fabaceae (12 species). The second largest used families represented were the Asteraceae and Zingiberaceae (10 species each), followed by the Lamiaceae (5), Caesalpiniaceae (4), and Amaranthaceae, Apiaceae, Cucurbitaceae, and Poaceae having 3 species each. The remainder of families was represented by two or one species. However, most of these families are documented to contain active constituents and feature in different traditional systems of medicine. Of all recorded species, herbs (55 species) were found to account for the greatest number, followed by trees (35 species), shrubs (13 species), climbers (10 species), and under-shrubs (4 species). Different parts of ethnomedicinal plants are used in herbal formulations by local traditional healers for the treatment of different ailments. Among such plant parts, leaves (34.07%) were found to be the most frequently used for the preparation of herbal drugs, followed by other parts (Fig. 2).

Considering the mode of preparation of traditional medicines by the Pangkhua community, the range of methods reported for various species included decoctions, juices, extracts, pastes, powders, infusions, oils, and the use of fresh plant parts. Among these, the most common formulations were decoctions (25.93%) and fresh plant parts (23.46%), followed by juices (16.05%), pastes (14.81%), extracts (13.58%), oils (3.70%), and infusions and powders (1.23% each). Decoctions are often the most commonly encountered preparation method reported [26,27,28,29,30]. In some cases, processing involved drying of the plant material followed by grinding into a fine powder. Water was most commonly used if a solvent was required, with cow’s milk or honey sometimes used as a matrix or as an adjuvant to increase viscosity. Within the study community, plant medicines were usually administrated orally. Bathing in a decoction or rubbing and massaging using the plant parts were also encountered.

Conservation status

The conservation status of all recorded plant species was checked using the International Union for Conservation of Nature (IUCN) Red List of Threatened Species [31]. A total of 12 species, namely Acorus calamus, Amorphophallus paeoniifolius, Ammania multiflora, Azolla pinnata, Breonia chinensis, Centella asiatica, Cyperus rotundus, Commelina diffusa, Hygrophila difformis, Lasia spinosa, Mimosa pudica, and Ottelia alismoides were recorded as “of Least Concern,” while only one species (Saraca asoca) was recorded as “vulnerable,” with all other species not included on the list.

Quantitative analysis

The present study records the use of ethnomedicines to treat 11 categories of ailments. Of these, the most common uses were for digestive system disorders (49 species), followed by respiratory complaints (39 species) (Table 3). To ascertain the level of agreement among the informants of the Pangkhua community regarding the use of plants to treat certain disease categories, FIC values were determined. The FIC values are presented in Table 3. It is clear that the FIC values showed variation, varying from 0.50 to 0.66. In the treatment of digestive system disorders, the highest FIC value (0.66) was encountered, with 141 use-reports for 49 plant species. This was followed by plants used to treat respiratory system disorders (FIC = 0.64) and so on (Table 3). In contrast, the least agreement (FIC = 0.50) between informants regarding therapeutic uses was observed for plants used to treat urinary disorders. The calculated JI indices (Table 4) ranged from 1.65 to 33.00. The highest degree of similarity was found with a study conducted in Bangladesh, while the lowest degree of similarity was found with a study conducted in Pakistan.

New ethnomedicinal plant species and uses

Our comparative analysis revealed that out of 117 ethnomedicinal plant species documented, 37 species had either no similar or any use (Table 1). Therefore, these species were compared with the research databases of SCOPUS, PubMed, Biomed Central, and Google Scholar, and the results showed that use of 12 of these species has heretofore been unreported in Bangladesh (Table 5), while 6 species have never been screened pharmacologically.

Discussion

Overall, this study revealed the traditional use of 117 plant species, distributed among 104 genera and belonging to 54 families to treat 11 categories of ailments, recorded from 218 traditional healers and elderly men and women. The highest number of species belonged to the Fabaceae; this dominancy may be due to the worldwide distribution of species from this family [32, 33] and, furthermore, that the Fabaceae constitute the second largest family in the flora of Bangladesh [2]. Similar results have been reported by other ethnobotanists [10, 27, 34] while [7] reported the Asteraceae as the largest family and the Fabaceae the third largest family in their study conducted in Bangladesh.

Herbs are naturally abundant in the study areas, which were mostly hilly and covered by a forest canopy, creating favorable conditions for their growth. Similar results were observed with other studies conducted in different regions of Bangladesh [3, 27, 34,35,36].

The preference for the use of leaves in the preparation of herbal medicines by the healers is likely due to the year-round availability of leaves, and the fact that they are easier to collect, store, process, and handle. Similar observations have been reported in allied studies in Bangladesh and other countries [28, 35, 37, 38]. Healers usually however prefer to use fresh plant materials instead of dry and stored ones for herbal preparations.

In the study area, digestive system disorders are common, largely due to a deficiency of pure water, especially in the dry season, coupled with a lack of awareness of its importance among those living in hilly and remote areas. Similarly, respiratory system disorders were second in occurrence, due to prevalence of smoking and chewing of leaves of Nicotiana tabacum with those of Piper betel. Analogously to our results, digestive system disorders were found to be the major ailment category in many other ethnomedicinal studies conducted in Bangladesh [7, 8, 14, 39, 40]. High FIC values also indicate that such species are worth investigating for bioactive compounds.

As discussed earlier, some medicinal plant species used by the healers of the studied community are also used by the healers of different communities in different parts of Bangladesh as well as in neighboring countries and beyond.

A total of 19 ethnomedicinal plant species which are commonly used by the indigenous communities of Bangladesh were selected and their known uses compared with our results (Table 6), to ascertain whether the Pangkhua community has any novel uses of these species. Alongside, we evaluated the phytochemical literature on these species. From our review, 11 species, namely Acorus calamus, Aegle marmelos, Arecha catechu, Calotropis procera, Centella asiatica, Curcuma longa, Justicia adhatoda, Phyllanthes emblica, Saraca asoca, Terminalia chebula, and Zingiber officinale have distinct uses within the Pangkhua community. For example, Centella asiatica is used analogously by the Marma community in Bandarban [35], the Rakhaing community in Cox’s Bazar [34], the Tripura community in Chittagong [3]; the local people in the Panchagarh [36], Garo, Hazong, and Bangalee communities in Durgapur [8]; the local people of 11 districts in Bangladesh [27]; and the ethnic people of western Nepal [41]. This species was also used differently in traditional medicine by traditional healers of Bangladesh and other countries [37, 42,43,44,45]. Interestingly, its use in one ailment, asthma, has been documented for the first time in this study. Similarly, the use of Acorus calamus as an anthelmintic has not been reported before, and the use of fruit of Aegle marmelos to treat asthma is recorded herein for the first time, while its leaves were used in combination with other plants [46]. Other unreported uses of established ethnomedicinal species include Arecha catechu as a carminative, Calotropis procera to treat asthma and snake bite, Curcuma longa as a laxative and to treat fever, Justicia adhatoda and Phyllanthes emblica to reduce high blood pressure, Saraca asoca to treat diarrhea and leucorrhea, Terminalia chebula to reduce pain during menstruation and to treat bronchitis, and Zingiber officinale as a laxative and to treat dyspepsia and tuberculosis.

To illustrate homogeneity of use or otherwise, the JI was used to compare our study with 43 previous investigations. In total, the JI was calculated for 28 regions of Bangladesh with the Cox’s Bazar district emerging as the most similar to our study area with JI = 33.00, followed by the Panchagarh, Chittagong, and Bandarban districts (JI = 22.83, 19.44, and 18.80 respectively), while the lowest JI (2.77) was found with the study conducted by Rahman [47]. The high JI may reflect that the study area is located in the same geological zone, with similar socioeconomic and cultural characteristics. On the other hand, among three neighboring countries (India, Pakistan, and Nepal), the highest similarity was found with the adjacent state of Tipura, India (JI = 11.74) while the lowest (JI = 1.65) was from Pakistan.

Limitations of the current study

Ethnobotanical documentation constitutes field-based research. Nevertheless, the field is not always a safe environment. A majority of the indigenous communities we studied live in forest areas, and there have been security risks due to rebel movement in these areas. It is risky to carry valuable field equipment like cameras, recorders, etc. Route access was limited to foot traffic. Language barriers were encountered, as most participants did not speak the national Bangla language requiring the use of interpreters. Seasonal variation is an important factor in the collection of voucher specimens, as in the rainy season it is difficult to both access and dry the specimens, while in the dry season the aerial parts of many plants have withered, coupled with the clearing of forest areas for cultivation during that period.

Indigenous peoples are sometimes unwilling to share their knowledge of medicinal plants with others, specifically the Bangali (Bangladeshi). They maintain the secrecy of medicinal plant use because there is a belief among them that the medicines lose their efficacy if too many people know of them, and additionally, they may be conscious about economic losses [48]. There may also be resistance to allowing themselves to become the subject of study by outsiders [48]. Therefore, potential informants must be encouraged using several techniques. Firstly, emphasis must be given to help them understand that shared information will be preserved for the benefit of their children and future generations. As their children are less frequently adopting the role of healers, without documentation, much knowledge of medicinal plants may disappear forever.

Research highlights

-

1.

The present study revealed that the Pangkhua community depends on a variety of ethnomedicinal plants to treat various diseases.

-

2.

Local herbalists are predominantly aging men and women, and the Pangkhua younger generation lacks interest in following the traditional role of the healer.

-

3.

While in many cases, the plants utilized by the Pangkhua are documented in allied literature, their preparation, mode of use, and clinical indication often differ from that of other indigenous communities.

-

4.

The information compiled herein constitutes a rich knowledge source for taxonomists, phytochemists, environmentalists, pharmacists, and allied professionals.

Conclusions

It can be concluded that the Pangkhua indigenous community of the Rangamati district of Bangladesh possess rich ethnomedicinal knowledge, as they use many medicinal plant species in their healthcare system. The novelty of this study is that 12 ethnomedicinal plant species have been recorded with new uses, and 6 of these species have never been screened pharmacologically. The traditional plants utilized have in some cases been validated scientifically by isolation of active ingredients, thus showing that traditional remedies are an important and effective part of indigenous healthcare systems in the district. Our findings will be helpful to ethnobotanists and phytochemists for conducting research into the isolation of active principles from these species. The preservation of these plant species is the gateway toward developing efficacious remedies for treating disease. Enhancing the sustainable use and conservation of indigenous knowledge of useful medicinal plants may benefit and improve the living standards of poor people. Hence, it is necessary to document the indigenous knowledge of useful plants and their therapeutic uses before they are lost forever.

Abbreviations

- CHTs:

-

Chittagong Hill Tracts districts

- FIC:

-

Factor of Informant Consensus

- IUCN:

-

International Union for Conservation of Nature

- JI:

-

Jaccard index

References

Yusuf M, Chowdhury J, Wahab M, Begum J: Medicinal plants of Bangladesh. Bangladesh Council of Scientific and Industrial Research, Dhaka, Bangladesh 1994, 192.

Pasha M, Uddin S: Dictionary of plant names of Bangladesh (vascular plants). Janokalyan Prokashani Chittagong, Dhaka, Bangladesh 2013:1–434.

Faruque O, Uddin SB. Ethnodiversity of medicinal plants used by Tripura community of Hazarikhil in Chittagong district of Bangladesh. J Taxon Biodiv Res. 2011;5:27–32.

Chowdhury MSH, Koike M, Muhammed N, Halim MA, Saha N, Kobayashi H. Use of plants in healthcare: a traditional ethno-medicinal practice in rural areas of southeastern Bangladesh. Int J Biodivers Sci Ecosyst Serv Manag. 2009;5:41–51.

Thomsen M, Halder S, Ahmed F: Medicinal and aromatic plant industry development. Inter-Cooperation, Dhaka, Bangladesh 2005.

Uddin S. Bangladesh ethnobotany online database; 2014.

Faruque MO, Uddin SB, Barlow JW, Hu S, Dong S, Cai Q, Li X, Hu X. Quantitative ethnobotany of medicinal plants used by indigenous communities in the Bandarban District of Bangladesh. Front Pharmacol. 2018;9:40.

Khan MA, Islam MK, Siraj MA, Saha S, Barman AK, Awang K, Rahman MM, Shilpi JA, Jahan R, Islam E. Ethnomedicinal survey of various communities residing in Garo Hills of Durgapur, Bangladesh. J Ethnobiol Ethnomed. 2015;11:44.

Khisha T, Karim R, Chowdhury SR, Banoo R. Ethnomedical studies of chakma communities of Chittagong hill tracts, Bangladesh. Bangladesh J Pharmacol. 2012;15:59–67.

Uddin SB, Faruque MO, Talukder S. A survey of traditional health remedies of the Chakma Indigenous community of Rangamati District, Bangladesh. J Plant Sci Res. 2014;1.

Rahmatullah M, Hossan MS, Hanif A, Roy P, Jahan R, Khan M, Chowdhury MH, Rahman T. Ethnomedicinal applications of plants by the traditional healers of the Marma tribe of Naikhongchhari, Bandarban district, Bangladesh. Adv Nat Appl Sci. 2009;3:392–401.

Sajib NH, Uddin S. Medico-botanical studies of Sandwip island in Chittagong, Bangladesh. Bangl J Plant Taxon. 2013;20:39.

Biswas A, Bari M, Roy M, Bhadra S. Inherited folk pharmaceutical knowledge of tribal people in the Chittagong hill tracts, Bangladesh. Indian J Tradit Know. 2010;9:77–89.

Kadir MF, Sayeed MSB, Mia M. Ethnopharmacological survey of medicinal plants used by indigenous and tribal people in Rangamati, Bangladesh. J Ethnopharmacol. 2012;144:627–37.

Islam A, Siddik AB, Hanee U, Guha A, Zaman F, Mokarroma U, Zahan H, Jabber S, Naurin S, Kabir H. Ethnomedicinal practices among a Tripura community in rangamati district, Bangladesh. Int J Pharm Pharm Sci. 2015;4:189–96.

Banglapedia. National Encyclopedia of Bangladesh. In: Asiatic Society of Bangladesh. Dhaka: Asiatic Society of Bangladesh; 2003.

Rao R. Methods and techniques in ethnobotanical study and research: some basic consideration. In: Jain SK, editor. Methods and Approaches in Ethnobotany - Society of Ethnobotanists, Lucknow. 1989. p. 13-23.

Given DR, Harris W. Techniques and methods of ethnobotany: as an aid to the study, evaluation, conservation and sustainable use of biodiversity. London: Commonwealth Secretariat Publications; 1994.

Alexiades MN, Sheldon JW. Selected guidelines for ethnobotanical research: a field manual. New York: New York Botanical Garden; 1996.

Martin GJ: Ethnobotany: a methods manual. London, UK: Earthscan; 1995.

Heinrich M, Ankli A, Frei B, Weimann C, Sticher O. Medicinal plants in Mexico: healers’ consensus and cultural importance. Soc Sci Med. 1998;47:1859–71.

Logan MH: Informant consensus: a new approach for identifying potentially effective medicinal plants. Plants in indigenous medicine and diet: biobehavioral approaches 1986, 91.

Heinrich M. Ethnobotany and its role in drug development. Phytother Res. 2000;14:479–88.

González-Tejero MR, Casares-Porcel M, Sánchez-Rojas CP, Ramiro-Gutiérrez JM, Molero-Mesa J, Pieroni A, Giusti ME, Censorii E, de Pasquale C, Della A, et al. Medicinal plants in the Mediterranean area: synthesis of the results of the project Rubia. J Ethnopharmacol. 2008;116:341–57.

Weckerle CS, de Boer HJ, Puri RK, van Andel T, Bussmann RW, Leonti M. Recommended standards for conducting and reporting ethnopharmacological field studies. J Ethnopharmacol. 2018;210:125–32.

Eissa TAF, Palomino OM, Carretero ME, Gómez-Serranillos MP. Ethnopharmacological study of medicinal plants used in the treatment of CNS disorders in Sinai Peninsula, Egypt. J Ethnopharmacol. 2014;151:317–32.

Kadir MF, Sayeed MSB, Mia M. Ethnopharmacological survey of medicinal plants used by traditional healers in Bangladesh for gastrointestinal disorders. J Ethnopharmacol. 2013;147:148–56.

Ong HG, Kim Y-D. Quantitative ethnobotanical study of the medicinal plants used by the Ati Negrito indigenous group in Guimaras island, Philippines. J Ethnopharmacol. 2014;157:228–42.

Sadat-Hosseini M, Farajpour M, Boroomand N, Solaimani-Sardou F. Ethnopharmacological studies of indigenous medicinal plants in the south of Kerman, Iran. J Ethnopharmacol. 2017;199:194–204.

Zheng X-l, Xing F-W. Ethnobotanical study on medicinal plants around Mt.Yinggeling, Hainan Island, China. J Ethnopharmacol. 2009;124:197–210.

IUCN: The IUCN Red List of Threatened Species. 2017. http://www.iucnredlist.org. Accessed 7 Feb 2018.

Marles RJ, Farnsworth NR. Antidiabetic plants and their active constituents. Phytomedicine. 1995;2:137–89.

Suleiman MHA. An ethnobotanical survey of medicinal plants used by communities of Northern Kordofan region, Sudan. J Ethnopharmacol. 2015;176:232–42.

Uddin SB, Ratna RS, Faruque MO. Ethnobotanical study on medicinal plants of Rakhaing Indigenous Community of Cox's Bazar District of Bangladesh. J Pharmacogn Phytochem. 2013;2:164–74.

Faruque M, Uddin S. Ethnomedicinal study of the Marma community of Bandarban district of Bangladesh. Acad J Med Plant. 2014;2:014–25.

Rahman KR, Faruque MO, Uddin SB, Hossen I. Ethnomedicinal knowledge among the local community of Atwari Upazilla of Panchagarh District, Bangladesh. Int J Trop Agric. 2016;34:1323–35.

Giday M, Asfaw Z, Woldu Z. Ethnomedicinal study of plants used by Sheko ethnic group of Ethiopia. J Ethnopharmacol. 2010;132:75–85.

Telefo P, Lienou L, Yemele M, Lemfack M, Mouokeu C, Goka C, Tagne S, Moundipa F. Ethnopharmacological survey of plants used for the treatment of female infertility in Baham, Cameroon. J Ethnopharmacol. 2011;136:178–87.

Sarker MN, Mahin AA, Munira S, Akter S, Parvin S, Malek I, Hossain S, Rahmatullah M. Ethnomedicinal plants of the Pankho community of Bilaichari Union in Rangamati district, Bangladesh. Am-Eur J Sustain Agr. 2013;7:114–20.

Uddin MZ, Hassan MA. Determination of informant consensus factor of ethnomedicinal plants used in Kalenga forest, Bangladesh. Bangl J Plant Taxon. 2014;21:83.

Malla B, Gauchan DP, Chhetri RB. An ethnobotanical study of medicinal plants used by ethnic people in Parbat district of western Nepal. J Ethnopharmacol. 2015;165:103–17.

Islam MK, Saha S, Mahmud I, Mohamad K, Awang K, Jamal Uddin S, Rahman MM, Shilpi JA. An ethnobotanical study of medicinal plants used by tribal and native people of Madhupur forest area, Bangladesh. J Ethnopharmacol. 2014;151:921–30.

Manandhar NP. A survey of medicinal plants of Jajarkot district, Nepal. J Ethnopharmacol. 1995;48:1–6.

Ocvirk S, Kistler M, Khan S, Talukder SH, Hauner H. Traditional medicinal plants used for the treatment of diabetes in rural and urban areas of Dhaka, Bangladesh–an ethnobotanical survey. J Ethnobiol Ethnomed. 2013;9:43.

Rajakumar N, Shivanna MB. Ethno-medicinal application of plants in the eastern region of Shimoga district, Karnataka, India. J Ethnopharmacol. 2009;126:64–73.

Das PR, Islam MT, Mostafa MN, Rahmatullah M. Ethnomedicinal plants of the Bauri tribal community of Moulvibazar district, Bangladesh. Anc Sci Life. 2013;32:144.

Rahman A. Ethno-medicinal investigation on ethnic community in the northern region of Bangladesh. Am J Life Sci. 2013;1:77–81.

Pal DC, Jain SK: Tribal medicine. Naya Prokash 206, Bidhan Sarani, Calcutta, India; 1998.

Akter S, Nipu AH, Chyti HN, Das PR, Islam MT, Rahmatullah M. Ethnomedicinal plants of the Shing tribe of Moulvibazar district, Bangladesh. World J Pharm Pharmaceut Sci. 2014;3:1529–37.

Kamal Z, Bairage JJ, Moniruzzaman DP, Islam M, Faruque M, Islam MR, Paul PK, Islam MA, Rahmatullah M. Ethnomedicinal practices of a folk medicinal practitioner in Pabna district, Bangladesh. World J Pharm Pharmaceut Sci. 2014;3:73–85.

Rahman A. Ethnomedicinal survey of angiosperm plants used by Santal tribe of Joypurhat District, Bangladesh. Int J Adv Res. 2015;3:990–1001.

Wahab A, Roy S, Habib A, Bhuiyan M, Roy P, Khan M, Azad AK, Rahmatullah M. Ethnomedicinal wisdom of a Tonchongya tribal healer practicing in Rangamati district, Bangladesh. Am-Eur J Sustain Agr. 2013;7:227–34.

Sarker B, Akther F, Sifa U, Jahan I, Sarker M, Chakma S, Podder P, Khatun Z, Rahmatullah M. Ethnomedicinal investigations among the Sigibe clan of the Khumi tribe of Thanchi sub-district in Bandarban district of Bangladesh. Am-Eur J Sustain Agr. 2012;6:378–86.

Hossan MS, Roy P, Seraj S, Mou SM, Monalisa MN, Jahan S, Khan T, Swarna A, Jahan R, Rahmatullah M. Ethnomedicinal knowledge among the Tongchongya tribal community of Roangchaari Upazila of Bandarban district, Bangladesh. Am-Eur J Sustain Agr. 2012;6:349–59.

Azam MNK, Ahmed MN, Rahman MM, Rahmatullah M. Ethnomedicines used by the Oraon and Gor tribes of Sylhet district, Bangladesh. Am-Eur J Sustain Agr. 2013;7:391–402.

Akhter J, Khatun R, Akter S, Akter S, Munni T, Malek I, Rahmatullah M. Ethnomedicinal practices in Natore district, Bangladesh. World J Pharm Pharmaceut Sci. 2016;5:212–22.

Azad A, Mahmud MR, Parvin A, Chakrabortty A, Akter F, Moury SI, Anny IP, Tarannom SR, Joy S, Chowdhury S. Ethnomedicinal surveys in two Mouzas of Kurigram district, Bangladesh. World J Pharm Pharmaceut Sci. 2014;3:1607–20.

Kosalge SB, Fursule RA. Investigation of ethnomedicinal claims of some plants used by tribals of Satpuda Hills in India. J Ethnopharmacol. 2009;121:456–61.

Singh A, Singh PK. An ethnobotanical study of medicinal plants in Chandauli District of Uttar Pradesh, India. J Ethnopharmacol. 2009;121:324–9.

Ijaz F, Iqbal Z, Rahman IU, Alam J, Khan SM, Shah GM, Khan K, Afzal A. Investigation of traditional medicinal floral knowledge of Sarban Hills, Abbottabad, KP, Pakistan. J Ethnopharmacol. 2016;179:208–33.

Aziz MA, Khan AH, Adnan M, Izatullah I. Traditional uses of medicinal plants reported by the indigenous communities and local herbal practitioners of Bajaur agency, federally administrated tribal areas, Pakistan. J Ethnopharmacol. 2017;198:268–81.

Khumbongmayum AD, Khan M, Tripathi R. Ethnomedicinal plants in the sacred groves of Manipur. Indian J Tradit Know. 2005;4:21–32.

Rai PK, Lalramnghinglova H. Ethnomedicinal plant resources of Mizoram, India: implication of traditional knowledge in health care system. Ethnobot Leaflets. 2010;14:274–305.

Sharma HK, Chhangte L, Dolui AK. Traditional medicinal plants in Mizoram, India. Fitoterapia. 2001;72:146–61.

Rai PK, Lalramnghinglova H. Lesser known ethnomedicinal plants of Mizoram, North East India: an Indo-Burma hotspot region. J Med Plants Res. 2010;4:1301–7.

Lalfakzuala R, Kayang H, Lalramnghinglova H. Ethnobotanical usages of plants in western Mizoram. Indian J Tradit Know. 2015;6:486–93.

Shil S, Choudhury MD, Das S. Indigenous knowledge of medicinal plants used by the Reang tribe of Tripura state of India. J Ethnopharmacol. 2014;152:135–41.

Sen S, Chakraborty R, De B, Devanna N. An ethnobotanical survey of medicinal plants used by ethnic people in west and south district of Tripura, India. J Forest Res. 2011;22:417.

Sajem AL, Gosai K. Traditional use of medicinal plants by the Jaintia tribes in North Cachar Hills district of Assam, Northeast India. J Ethnobiol Ethnomed. 2006;2:33.

McGaw L, Jäger A, Van Staden J, Eloff J. Isolation of β-asarone, an antibacterial and anthelmintic compound, from Acorus calamus in South Africa. S Afr J Bot. 2002;68:31–5.

Faruque O, Uddin S. Ethnodiversity of medicinal plants used by Tripura community of Hazarikhil in Chittagong district of Bangladesh. J Taxon Biodiv Res. 2011;5:27–32.

Islam MK, Saha S, Mahmud I, Mohamad K, Awang K, Uddin SJ, Rahman MM, Shilpi JA. An ethnobotanical study of medicinal plants used by tribal and native people of Madhupur forest area, Bangladesh. J Ethnopharmacol. 2014;151:921–30.

Gangadevi V, Muthumary J. Taxol, an anticancer drug produced by an endophytic fungus Bartalinia robillardoides Tassi, isolated from a medicinal plant, Aegle marmelos Correa ex Roxb. World J Microbiol Biotechnol. 2008;24:717.

Mishra BB, Singh DD, Kishore N, Tiwari VK, Tripathi V. Antifungal constituents isolated from the seeds of Aegle marmelos. Phytochemistry. 2010;71:230–4.

Phuwapraisirisan P, Puksasook T, Jong-Aramruang J, Kokpol U. Phenylethyl cinnamides: a new series of α-glucosidase inhibitors from the leaves of Aegle marmelos. Bioorg Med Chem Lett. 2008;18:4956–8.

Zhang XF, Wang HM, Song YL, Nie LH, Wang LF, Liu B, Shen PP, Liu Y. Isolation, structure elucidation, antioxidative and immunomodulatory properties of two novel dihydrocoumarins from Aloe vera. Bioorg Med Chem Lett. 2006;16:949–53.

Lawrence R, Tripathi P, Jeyakumar E. Isolation, purification and evaluation of antibacterial agents from Aloe vera. Braz J Microbiol. 2009;40:906–15.

Lee KH, Kim JH, Lim DS, Kim CH. Anti-leukaemic and anti-mutagenic effects of Di (2-ethylhexyl) phthalate isolated from aloe vera Linne. J Pharm Pharmacol. 2000;52:593–8.

Yenjit P, Issarakraisila M, Intana W, Chantrapromma K. Fungicidal activity of compounds extracted from the pericarp of Areca catechu against Colletotrichum gloeosporioides in vitro and in mango fruit. Postharvest Biol Tech. 2010;55:129–32.

Uchino K, Matsuo T, Iwamoto M, Tonosaki Y, Fukuchi A. New 5′-nucleotidase inhibitors, NPF-86IA, NPF-86IB, NPF-86IIA, and NPF-86IIB from Areca catechu; part I. Isolation and biological properties. Planta Med. 1988;54:419–22.

Kraus W, Bokel M, Bruhn A, Cramer R, Klaiber I, Klenk A, Nagl G, Pöhnl H, Sadlo H, Vogler B. Structure determination by NMR of azadirachtin and related compounds from Azadirachta indica A. Juss (Meliaceae). Tetrahedron. 1987;43:2817–30.

Kabir MH, Hasan N, Rahman MM, Rahman MA, Khan JA, Hoque NT, Bhuiyan MRQ, Mou SM, Jahan R, Rahmatullah M. A survey of medicinal plants used by the Deb barma clan of the Tripura tribe of Moulvibazar district, Bangladesh. J Ethnobiol Ethnomed. 2014;10:19.

Saratha V, Pillai SI, Subramanian S. Isolation and characterization of lupeol, a triterpenoid from Calotropis gigantea latex. Int J Pharm Sci Rev Res. 2011;10:54–7.

Sen S, Sahu NP, Mahato SB. Flavonol glycosides from Calotropis gigantea. Phytochemistry. 1992;31:2919–21.

Shaker KH, Morsy N, Zinecker H, Imhoff JF, Schneider B. Secondary metabolites from Calotropis procera (Aiton). Phytochem Lett. 2010;3:212–6.

Ibrahim SR, Mohamed GA, Shaala LA, Banuls LMY, Van Goietsenoven G, Kiss R, Youssef DT. New ursane-type triterpenes from the root bark of Calotropis procera. Phytochem Lett. 2012;5:490–5.

Daisy P, Balasubramanian K, Rajalakshmi M, Eliza J, Selvaraj J. Insulin mimetic impact of Catechin isolated from Cassia fistula on the glucose oxidation and molecular mechanisms of glucose uptake on streptozotocin-induced diabetic Wistar rats. Phytomedicine. 2010;17:28–36.

Duraipandiyan V, Ignacimuthu S. Antifungal activity of rhein isolated from Cassia fistula L. flower. Webmed Central Pharmacol. 2010;1:2010.

Azad A, Mahmud MR, Parvin A, Chakrabortty A, Akter F, Moury SI, Anny IP, Tarannom SR, Joy S, Chowdhury S. Medicinal plants of a Santal tribal healer in Dinajpur district, Bangladesh. World J Pharm Pharmaceut Sci. 2014;3:1597–606.

Nhiem NX, Tai BH, Quang TH, Van Kiem P, Van Minh C, Nam NH, Kim J-H, Im L-R, Lee Y-M, Kim YH. A new ursane-type triterpenoid glycoside from Centella asiatica leaves modulates the production of nitric oxide and secretion of TNF-α in activated RAW 264.7 cells. Bioorg Med Chem Lett. 2011;21:1777–81.

Rahmatullah M, Mollik AH, Khatun A, Jahan R, Chowdhury AR, Seraj S, Hossain MS, Nasrin D, Khatun Z. A survey on the use of medicinal plants by folk medicinal practitioners in five villages of Boalia sub-district, Rajshahi district, Bangladesh. Adv Nat Appl Sci. 2010;4:39–45.

Revathy S, Elumalai S, Antony MB. Isolation, purification and identification of curcuminoids from turmeric (Curcuma longa L.) by column chromatography. J Exp sci. 2011;2(7):21-5.

He X-G, Lin L-Z, Lian L-Z, Lindenmaier M. Liquid chromatography–electrospray mass spectrometric analysis of curcuminoids and sesquiterpenoids in turmeric (Curcuma longa). J Chromatogr A. 1998;818:127–32.

Rahman M, Hossan MY, Aziz N, Mostafa MN, Mahmud MS, Islam MF, Seraj S, Rahmatullah M. Home remedies of the Teli clan of the Telegu tribe of Maulvibazar district, Bangladesh. Am-Eur J Sustain Agr. 2013:290–5.

Jha DK, Panda L, Lavanya P, Ramaiah S, Anbarasu A. Detection and confirmation of alkaloids in leaves of Justicia adhatoda and bioinformatics approach to elicit its anti-tuberculosis activity. Appl Biochem Biotechnol. 2012;168:980–90.

Rahmatullah M, Mollik MAH, Harun-or-Rashid M, Tanzin R, Ghosh KC, Rahman H, Alam J, Faruque MO, Hasan MM, Jahan R. A comparative analysis of medicinal plants used by folk medicinal healers in villages adjoining the Ghaghot, Bangali and Padma Rivers of Bangladesh. Am-Eur J Sustain Agr. 2010:70–86.

Patil R, Patil R, Ahirwar B, Ahirwar D. Isolation and characterization of anti-diabetic component (bioactivity—guided fractionation) from Ocimum sanctum L.(Lamiaceae) aerial part. Asian Pac J Trop Med. 2011;4:278–82.

Kumaran A, Karunakaran RJ. Nitric oxide radical scavenging active components from Phyllanthus emblica L. Plant Foods Hum Nutr. 2006;61:1.

Sadhu SK, Khatun A, Phattanawasin P, Ohtsuki T, Ishibashi M. Lignan glycosides and flavonoids from Saraca asoca with antioxidant activity. J Nat Med. 2007;61:480–2.

Varghese GK, Bose LV, Habtemariam S. Antidiabetic components of Cassia alata leaves: identification through α-glucosidase inhibition studies. Pharm Biol. 2013;51:345–9.

Rahaman M, Hasan AM, Ali M, Ali M. A flavone from the leaves of Cassia alata. Bangladesh J Sci Ind Res. 2006;41:93–6.

Cuervo AC, Blunden G, Patel AV. Chlorogenone and neochlorogenone from the unripe fruits of Solanum torvum. Phytochemistry. 1991;30:1339–41.

Lu Y, Luo J, Huang X, Kong L. Four new steroidal glycosides from Solanum torvum and their cytotoxic activities. Steroids. 2009;74:95–101.

Sudjaroen Y, Haubner R, Würtele G, Hull W, Erben G, Spiegelhalder B, Changbumrung S, Bartsch H, Owen R. Isolation and structure elucidation of phenolic antioxidants from tamarind (Tamarindus indica L.) seeds and pericarp. Food Chem Toxicol. 2005;43:1673–82.

Wong K, Tan C, Chow C, Chee S. Volatile constituents of the fruit of Tamarindus indica L. J Essent Oil Res. 1998;10:219–21.

Karim S, Rahman M, Shahid SB, Malek I, Rahman A, Jahan S, Jahan FI, Rahmatullah M. Medicinal plants used by the folk medicinal practitioners of Bangladesh: a randomized survey in a village of Narayanganj district. Am-Eur J Sustain Agr. 2011:405–15.

Reddy DB, Reddy T, Jyotsna G, Sharan S, Priya N, Lakshmipathi V, Reddanna P. Chebulagic acid, a COX–LOX dual inhibitor isolated from the fruits of Terminalia chebula Retz., induces apoptosis in COLO-205 cell line. J Ethnopharmacol. 2009;124:506–12.

Manosroi A, Jantrawut P, Akazawa H, Akihisa T, Manosroi J. Biological activities of phenolic compounds isolated from galls of Terminalia chebula Retz.(Combretaceae). Nat Prod Res. 2010;24:1915–26.

Mukti M, Ahmed A, Chowdhury S, Khatun Z, Bhuiyan P, Debnath K, Rahmatullah M. Medicinal plant formulations of Kavirajes in several areas of Faridpur and Rajbari districts, Bangladesh. Am-Eur J Sustain Agr. 2012;6:234–47.

Chen C-C, Rosen RT, Ho C-T. Chromatographic analyses of isomeric shogaol compounds derived from isolated gingerol compounds of ginger (Zingiber officinale Roscoe). J Chromatogr A. 1986;360:175–84.

Hasan SA, Uddin M, KNU H, Das A, Tabassum N, Hossain R, Mahal MJ, Rahmatullah M. Ethnomedicinal plants of two village folk medicinal practitioners in Rajshahi district, Bangladesh: comparison of their folk medicinal uses with Ayurvedic uses. Am-Eur J Sustain Agr. 2014:10–20.

Acknowledgements

The authors express their deep sense of gratitude to the informants and the Bangali men and women who helped them in many different ways during the field work. The authors declare there is no actual or potential conflict of interest pertinent to this study.

Funding

This research was supported by the Natural Science Foundation of Hubei Province, China, No. 2015CFA091 (XH), the Fundamental Research Funds for the Central Universities Program No. 2015PY181 (XH), No. 2662017PY104(XH) and National Key R&D Program of China 2017YFD0501500 (XH).

Availability of data and materials

All documented data will be included online at www.ebbd.info and www.mpbd.info.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

MOF, GF, SBU, and JB conceived and designed the experiments. MOF, MNAK, and URA collected the data. MOF, GF, SH, URA, and MK analyzed the data. MOF, JB, XH, and SBU wrote the manuscript. All of the listed authors have read and approved the submitted final manuscript.

Corresponding authors

Ethics declarations

Ethical approval and consent to participate

There are no formal rules and regulations governing consent from participants in Bangladesh regarding the sharing of ethnomedicinal knowledge. For the purposes of our study, a consistent approach was established. Each participant agreed to participate voluntarily. The research study was explained to all participants prior to interview. Participants were allowed to discontinue the interview at any time. For collecting voucher specimens, permission was taken from the appropriate body/owner/informants.

Completing of interests

The authors declare that they have no competing of interest.

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Additional files

Additional file 1:

Group interview. There were 28 Pangkhua people present while we were conducting an interview about ethnomedicinal plant usage. We considered all 28 Pangkhua people as informants, due to each person having some knowledge regarding ethnomedicines. (TIF 6452 kb)

Additional file 2:

List of 218 informants in the study, alongside their demographic characteristics (traditional healers highlighted in red). The detailed descriptions of all 218 informants, including their age, sex, location, education, and occupation were documented from the studied areas. (XLSX 19 kb)

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/), which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made. The Creative Commons Public Domain Dedication waiver (http://creativecommons.org/publicdomain/zero/1.0/) applies to the data made available in this article, unless otherwise stated.

About this article

Cite this article

Faruque, M.O., Feng, G., Khan, M.N.A. et al. Qualitative and quantitative ethnobotanical study of the Pangkhua community in Bilaichari Upazilla, Rangamati District, Bangladesh. J Ethnobiology Ethnomedicine 15, 8 (2019). https://doi.org/10.1186/s13002-019-0287-2

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/s13002-019-0287-2