Abstract

Background

The consumption of wild plants is an ancient tradition which serves multiple purposes. Cognizant that Teso-Karamoja region is frequently affected by food scarcity and is not adequately surveyed for its flora, this study sought to establish an inventory and use of wild edible plants by the communities living in and around the forest reserves.

Methods

Data was collected using semi-structured questionnaires administered to 240 respondents living in and around eight forest reserves between November 2017 and May 2018. One focus group discussion (8–12 members) per forest reserve and field excursions to collect the plant voucher specimens were also conducted. The data was analyzed using descriptive statistics, relative frequency of citation (RFC), and the factor of informants’ consensus (FIC).

Results

A total of 100 plant species in 47 families were reported as edible. Carissa spinarum, Strychnos innocua, Balanites aegyptiaca, Tamarindus indica, and Ximenia americana presented the highest RFC, while the families Rubiaceae, Fabaceae, Anacardiaceae, Amaranthaceae, and Moraceae had more than five species each. Grasses (Poaceae) comprised only 1% of the edible species and trees 35%, while shrubs were the most important source of wild food (RFC = 0.47). The fruits contributed 63% while leaves (29%), seeds (9%), tubers (5%), and gum (1%). The fruits were considered as the most important use category (RFC = 0.78). Respondent homogeneity was none for gum but very high for seeds (FIC - 0.93). Only 36% of species are cooked, while 64% are eaten in raw. Harvesting is done rudimentarily by digging (5%), collecting from the ground (fruits that fall down) (13%), and plucking from mother plants (82%). Only 9% of the species were collected throughout the year, 27% in the dry season, and 64% in the rainy season. The consumption of these plants is attributed to food scarcity, spicing staple food, nutri-medicinal value, cultural practice, and delicacy.

Conclusion

A high diversity of wild edible plant species exists in the forest reserves of Teso-Karamoja region. The shrubs and fruits are the most locally important life forms and use category, respectively. These edible plant species are important throughout the year because their consumption serves multiple purposes.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

The consumption of wild edible plants is an ancient phenomenon which predates agriculture [1]. These plants offer various benefits and opportunities to communities; for example, they enable communities to cope with food scarcity [2,3,4]. This is also known as ecosystem-based adaptation (EbA) [5]. They hold great cultural significance to dependent communities [6]. In addition, wild edible plants increase the nutritional quality of rural diets for instance, micronutrients (vitamins and minerals) which are sometimes superior to those of domesticated varieties [7]. Some of them also contain genes that can be sought to improve the productivity of cultivars [8]. They also contribute to household incomes [9], thereby contributing to the attainment of sustainable development goal 1 on eradicating poverty.

The selection of plants for ethnobotanical use is anchored in a theory. The theories include among others the optimal foraging theory [10] and theory of non-random plant selection [11]. The former predicts that foraging organisms will balance the effort it took to search for and eat that food. In so doing, individuals will place high value on plants that yield more benefit per unit of foraging/processing time; as abundance of plants with higher value increases, plants with lower value will no longer be used and individuals should have a quantitative threshold to decide when a specific plant should be included or excluded [12]. The latter theory asserts that plant selection is not random because species in the same family share some characteristics inherited from common ancestors (evolutionary relatedness) which in turn influence their physiology and ultimately their ethnobotanical use.

The global population facing food and nutritional insecurity increased from 777 million in 2015 to 815 million in 2016 [13]. In the same report, the percentage of population in Sub-Saharan and East Africa that was chronically undernourished was estimated to be 22.7 and 33.9%, respectively. In Uganda, an estimated 10.9 million people of the 40 million people experienced acute food insecurity in 2017 with Teso and Karamoja among the most affected areas [4]. These statistics underline the fact that food scarcity is one of the most pressing problems facing humanity globally [14]. The scarcity of food is largely caused by intermittent rainfall patterns which cause crop failure [4], warfare, poverty, and landlessness [15]. Unfortunately, these factors are still at play in most parts of the world and could be worsened by the effects of climate change being experienced.

In as much as intensification of agriculture and biotechnology can offer remedies to food scarcity, the role of wild edible plants cannot be under estimated [14]. They have been reported to make a significant proportion to the global food basket [16]. For instance, in 2014, it was estimated that approximately one billion people globally use wild food plants to supplement their diets [17]. Indeed, in most African communities, the tradition of gathering and consuming wild food plants still persists [9, 15] despite reliance on a few staple crops and huge investments in agriculture [18]. Therefore, it is urgent to recognize the contribution of these plants to food and nutritional security in communities that still use them.

Notwithstanding the contribution of wild edible plants, their diversity and the associated indigenous knowledge (IK) globally have not been documented sufficiently [19]. This situation is worsened by the rampant loss of biological resources [20] and erosion of the associated indigenous knowledge [21, 22]. According to the state of the 2016 world’s plants report, it was estimated that one in every five plants is at risk of extinction globally [23]. In Teso-Karamoja region, it has been reported that 77, 66, and 45% of the natural vegetation cover has been lost in the districts of Katakwi, Kotido, and Kaberamaido districts, respectively [24].

The consumption of wild edible plants in Uganda has been investigated by various scholars in different locales [25,26,27,28,29]. Despite these efforts, it is acknowledged that the diversity of species used is determined by culture and the location [30]. This partly explains why most values of underutilized plants remain undocumented and often not reflected in national and international markets [31, 32]. Consequently, this situation greatly undermines their conservation and sustainable utilization [33]. This ethnobotanical study was warranted due to the information paucity created by cultural and biogeographical diversity, rampant food scarcity [4], and the few botanical surveys in Teso-Karamoja region due to a history of armed conflicts [34]. The study adopted the availability and diversification hypotheses [35], plant use value hypothesis [36], and the versatility hypothesis [37]. These hypotheses helped to generate information pertaining to the diversity of wild edible plant species used, presence or absence of exotics, relative importance of each species and use categories, relative importance of the different lifeforms, seasonal availability, and importance of these plants in the eight forest reserves.

Materials and methods

Study area

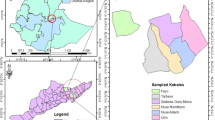

The study was conducted in eight forest reserves in Teso-Karamoja. They include Onyurut, Bululu Hill, and Ogera Hills (Teso) and Akur, Kano, Mount Napak, Mount Kadam, and Mount Moroto (Moroto). These forest reserves comprise of woodlands, shrublands, and grasslands [24]. They were selected because they are of ecological and biodiversity importance [38]. Secondly, they lacked comprehensive wild edible plant species inventories at the commencement of this study.

Teso sub-region experiences a humid and hot climate with rainfall between 1000 and 1350 mm per annum with the large swamp network playing a moderating role [39]. The sub-region lies at a lower altitude than Karamoja and Sebei sub-regions of Uganda, thereby receiving water discharges which occasionally cause flooding [39]. It is located in the U1 floristic region of the Flora of Tropical East Africa (FTEA) [34]. All the forest reserves herein are predominantly woodlands, bushlands, and grasslands [24].

Karamoja is mainly comprised of semi-arid lands inhabited by pastoralists and agro-pastoralists [3]. It is located in the U3 floristic region of FTEA [34]. The five forest reserves in this sub-region selected for this study are mountainous. All the forest reserves are composed of woodlands, bushlands, and grasslands [24]. However, the South, North, and Eastern escarpment are forested and mountainous areas similar to the well-watered West (Abim district) which has a high vegetation cover comprising of bushlands and woodlands [4]. The lower altitude forests receive variable, unpredictable, and sparse rainfall ranging from 500 to 800 mm per annum while the highlands receive higher amounts. The temperatures are generally high all year round [4].

Data collection

Data was collected using semi-structured questionnaires administered to 240 respondents living in and around eight forest reserves (Fig. 1) between November 2017 and May 2018. This sample size was determined using Yamane formula for sample size at 95% confidence level [40]. The communities living either in or around each forest reserve were purposely prioritized in the ethnobotanical survey since they have direct interface with the forest reserves. A single village within 1–5 km radius was purposively selected to take part in the survey. The respondents comprised of males and females of different ethnicities, namely Iteso, Kumam, Acholi-Labwor, Tepeth, Bokora, and the Kadam. The first respondent was taken from the first household encountered when approaching a sampling village. Thereafter, systematic simple random sampling was applied until the required sample size was obtained.

The free listing technique [41] was used to capture data on plant identity, the mode of harvesting, consumption mode, and availability patterns. This technique allows the respondents to state the plant name that comes to his/her mind until they are exhausted. In order to corroborate the information gathered in the questionnaires, one focus group discussion with 8–12 respondents was conducted in each forest reserve. These were respondents who stated the highest number of wild edible plant species and were therefore deemed to be more knowledgeable. Field excursions were undertaken with assistance of two male respondents to collect the voucher specimens of the plants enumerated. The voucher specimens were pressed, dried, and identified at the Makerere University Herbarium. The acceptable scientific names were obtained from the catalog of life (http://www.catalogueoflife.org/) while the global conservation status was obtained from the IUCN Red List of Threatened Species (https://www.iucnredlist.org/).

Data analysis

The data was collated, analyzed using descriptive statistics, and presented using tables and figures. The relative frequency of citation (RFC) was determined for each species as the ratio of respondents who mentioned a particular species to the total number of respondents in the study [42]. In addition, RFC was computed for each use category, lifeform, and season. The RFC values range from 0 to 1 and are a measure of the relative importance. Furthermore, the informants’ consensus factor (FIC) was computed for each used category in order to determine the homogeneity of information given by respondents [43] using a formula FIC = Nur − Nt/(Nur − 1), where Nur is the number of used reports from informants for a particular plant use category and Nt is the number of taxa or species that are used for that plant use category of wild edible plant species.

Results

Socio-economic characteristics of respondents

A total of 54% female and 46% male respondents were interviewed. They had varying levels of education whereby 36% had no formal education, 42% primary level, 19% secondary level, and only 3% tertiary level. The respondents comprised of 91% peasant farmers rearing livestock and/or growing crops, 4% petty traders, and 3% fishers while 2% were civil servants.

Diversity of wild edible plant species

This study has established an inventory of 100 wild edible plant species belonging to 47 families in eight forest reserves of Teso-Karamoja region (Table 1). The average number of species mentioned by a respondent was 10 (Table 2). The five plant species with the highest RFC are Carissa spinarum L., Strychnos innocua Delile, Balanites aegyptiaca (L) Delile, Tamarindus indica L., and Ximenia Americana L. (Fig. 2). The highest number of edible plant species was recorded in Mt. Kadam forest reserve (40) while the lowest was in Ogera hills forest reserve (17) (Fig. 3). There was also a similarity of species across some of the forest reserves with C. spinarum, Vitex madiensis Oliv., X. americana, and T. indica occurring in all the reserves. The families Rubiaceae, Fabaceae, Amaranthaceae, Anacardiaceae, and Moraceae had five edible species each.

Lifeforms of wild edible plant species

The wild edible plant species belong to five lifeforms namely grass, forbs, shrubs, trees, and climbers. Trees contributed 35% while the grasses contributed only 1.0% of all the identified species (Fig. 4). It is further noted that the shrubs are the most important source of wild food (RFC = 0.47) while grass are the least (RFC = 0.00) (Fig. 5).

Use categories of wild edible plant species

Five use categories of wild edible plants have been documented in Teso-Karamoja region. These are fruits, vegetables, seeds, tubers, and gum (Fig. 6). Fruits were provided by 63% of the species while those providing gum comprised 1%. Most of species provide food that is eaten without cooking (64%) while the reminder (34%) requires cooking. Some of the species eaten without cooking are fruits from C. spinarum, Psilotrichum axilliflorum Suess, and V. doniana. Respondents agreed that fruits were the most important use value of wild edible plants (RFC = 0.78) (Fig. 7). The relative importance of fruits, vegetables, and gum concurs with the prominence of species consumed in each category except for tubers which are relatively more important than seeds. There was no respondent homogeneity in the use of gum for food whilst it was almost homogenous for seeds (RFC = 0.93) (Table 3).

Seasonality of wild edible plant species

The seasons in Teso-Karamoja region are broadly divided into dry (November to March) and rainy (April to October). The species used throughout the year comprise 9%, rainy season 64%, and dry season 27% (Table 1). The main plants in the dry season include T. indica and B. aegyptiaca while the rainy season species includes C. spinarum, V. paradoxa, and V. madiensis. It was observed that members of the community preserved and stored some of the plants in order to guarantee supply during the off-peak seasons. The species mentioned include T. indica, V. paradoxa, and Dioscorea sp. The relative seasonal importance of the wild edible plant species shows that they are more important in the rainy season (RFC = 0.55) than in the dry season (RFC = 0.40) and throughout the year (RFC = 0.05).

Preference of wild edible plant species

The consumption of wild edible plant species was premised on five reasons, namely (i) hunger due to food scarcity, (ii) spicing staple food, (iii) preservation of cultural practice, (iv) nutri-medicinal value, and (v) their delicacy. Zanthoxylum leprieurii Guill. & Perr was commonly mentioned nutri-medicinal plant for flavoring tea but also used in treating various ailments.

Harvesting techniques

Wild edible plants were mainly harvested using three rudimentary methods, namely digging (tubers and roots), plucking from plants (fruits, seeds, and gum), and ground collection of fallen seeds and fruits. The prominence of these techniques was in the order of plucking from mother plants (82%), collecting from the ground (13%), and digging (5%).

Global conservation status of wild edible plant species

The only globally threatened plant species recorded in this study are P. axilliflorum (endangered), Mitragyna stipulosa (DC.) Kuntze (Vulnerable), and Vitellaria paradoxa C.F.Gaertn (vulnerable). The rest are either least concern (LC), data deficient (DD), or not evaluated (NE) (Fig. 8). The voucher specimens of five plants could not be identified up to the species level and were ultimately not assigned to any of the IUCN categories.

Discussion

The high diversity of wild edible plant species (Table 1) in Teso-Karamoja region demonstrates that people in and around forest reserves possess information about local vegetation that provides food. This is in tandem with the availability hypothesis [35] which asserts that people use plants that are more accessible or locally abundant. It ought to be noted that availability is often conceptualized as a physical distance from a home or community to the location where the plant grows in the wild but can also be considered in terms of seasonality, abundance, and price as well as access to markets, gardens, or natural areas where the plants are found [35]. The number of species recorded in this study is comparable to the 114 edible plant species (57 families) reported in the Eastern Arc Mountains of Tanzania [6]. However, it is also higher than the 77 species reported in Ethiopia [44], 72 species in Kenya [45], and 52 species reported in the Middle Agri Valley of Italy [46]. This variance in the diversity of edible wild plant species has been attributed to disparities in culture and location [30]. The Rubiaceae, Fabaceae, Anacardiaceae, Amaranthaceae, and Moraceae families are widely known to be among the largest and economically important sources of food and are widespread in the tropics [9].

The presence of exotic species namely Passiflora edulis Sims., Carica papaya L., Solanum lycopersicum L., Lantana camara L., Musa paradisiaca L., Psidium guajava L., and Amaranthis hybridus L. subsp. cruentus (L) Thell among the wild edible plants in this region is evidence for the diversification hypothesis [35]. The incorporation of exotic plants in traditional diets enriches culture as opposed to being a sign of cultural erosion or environmental degradation. These exotics exist as weedy escapees, naturalized, or invasive species while some of them such as P. edulis, P. guajava, C. papaya, A. hybridis, M. paradisiaca, and S. lycopersicum can be purposively cultivated.

All the forest reserves investigated are woodlands, and this partly explains why the trees represent the majority of edible plant species (Fig. 4), they are not the most important sources of wild food (Fig. 5). This information is very useful in prioritizing wild plant species for domestication initiatives or in situ conservation and further investigation of their nutritional and mineral quality. Again, the number of species in each lifeform is dynamic and varies from one ecological niche to another. While herbs were the majority amongst the subsistence farming communities of Amuria district, Uganda [47], in Nhema Communal Area, Midlands Province, Zimbabwe, trees comprised the majority of edible species [9]. These results conform to the plant use value hypothesis proposition that the usefulness of a plant for food, medicine, construction, technology, or trade in any community is directly related to its botanical family, lifeform, local abundance, and/or maximum size [36].

The fruits were considered the most important use category (Fig. 7) because they require no sophisticated means of preparation. The average number of wild edible plant species in Table 2 affirms the relative importance of the five use categories in Fig. 7. They are often eaten opportunistically as one is undertaking other core activities such as gardening, grazing, collecting firewood, fetching water, or hunting. Whereas opportunistic collection of wild edible plants was attributed to only women and children during firewood or water fetching [48], our findings reveal that even adult males engaged in hunting, livestock grazing, gardening, and collecting construction materials opportunistically forage wild edible plants. Generally, the fondness of an edible part is attributable to the ease of processing, nutritional value, and the taste [18].

The procedure for preparing V. kirkii (Baker) J.B.Gillett and S. obtusifolia (L.) H.S.Irwin & Barneby vegetable sauce is similar, namely plucking fresh leaves, brief wilting under direct sunlight for approximately 30 min, washing, and then boiling. In order to ensure proper cooking, local salt called “Abalang” (filtrate from ash of selected plants) is added, and then, sodium chloride is added to give a good taste. This can be eaten at this stage, or sour milk, groundnut, or simsim paste are added to spice it (Plate 1). The peculiarity in Maerua angolensis DC, and L. hastata, is pounding (using a mortar and pestle) after boiling and no addition of the local salt. In the case of Dioscera sp. tubers, they are washed (occasionally peeled), boiled, and salted (sodium chloride), and it is ready to be eaten.

According to the optimal foraging theory [10], the results obtained in this study imply that the most economically advantageous foraging pattern is eating fruits. This theory asserts that although obtaining food provides an individual with energy, searching and capturing it also requires energy and time. This underpinning ably explains why adults interviewed abandoned the consumption of certain plants such as S. innocua and S. birrea to children although they are familiar with them but the energy and time invested in obtaining them is not commensurate with the resultant value. This tendency has also been reported in Zimbabwe [9, 48]. Generally, humans contemplate the choice of their food by considering its nutritional benefit together with the cost of searching, handling, and collecting it [49].

The lack of respondent agreement on the use of gum as food (Table 3) is largely because it is only chewed without swallowing in worse-case scenarios of hunger. It is also probable that this observation is an outlier. However, the loss of indigenous knowledge about edible wild plants [50] change in the livelihood patterns that limit the amount of time spent foraging in the wild [51] and a general shift from gathered to purchased foods as rural communities join the market economy [52] could be responsible for this scenario. Whereas the gatherer to purchaser scenario exists in Teso-Karamoja, the most applicable scenario could be described as gatherer to purchased, cultivated, and sometimes donated (relief) food.

The relatively high importance of wild edible plants in the rainy season coincides with the time when most species are re-sprouting, flowering, and fruiting, thereby increasing their availability. It ought to be stressed that during the rainy season, most households are able to produce food from a range of crops and therefore have a wide range of choice, but still wild edible plants are important. In the dry season, communities are solely dependent on stored food and the wild edible plants (especially vegetables) help to diversify the food intake. This seasonal relative importance greatly impacts households’ food and nutritional insecurity copying ability. Earlier scholars have asserted that in times of food scarcity, wild edible plants make human diets more diverse and add flavor, vitamins, and minerals [53]. Globally, wild edible plants have been recognized as a key component in ecosystem-based adaptation [5] and food scarcity copying strategy [2].

The factors put forward for using wild edible plants in Teso-Karamoja region exemplify the vital role they play in the community. Therefore, even if every rural household had enough food in this region, the use of wild edible plants would still exist. There is a need to ensure that the biological resources and the associated indigenous knowledge are safeguarded for posterity, where both the biological resources and the cultural heritage of these communities shall be preserved. It has also been established that wild edible plants harbor great cultural significance to rural populations in developing countries [6] and their attachment to culture partly explains why the ancient hunter-gatherer tradition still persists in some African communities [9, 15]. This conforms to the proposition of the versatility hypothesis that people are more likely to retain their knowledge and the use and access to a plant that has a greater value for humans [37].

All the methods used to harvest wild edible plants in this region can be termed as rudimentary and therefore pose less deleterious effects to the plant species. However, where they involve cutting of branches in order to pluck off edible vegetables such as in B. aegyptiaca and M. angolensis, the growth and survival of the plant is greatly hampered. Another deleterious example is the collection of the tubers by digging. These cases imply that forest reserve management plans ought to consider regulated collection of such peculiar plants in order to minimize any detrimental effects. Awareness that most rural communities in Teso-Karamoja region (Uganda generally) feel aggrieved by most forest conservation measures, streamlining the collection of wild edible plants as a trade-off could be a step towards garnering the support of these communities.

The most threatened plant species encountered in this study is P. axilliflorum. This is an endangered species which is endemic to the Democratic Republic and Congo (DRC) and Uganda [54]. In Uganda, it was only recorded in Budongo Central Forest Reserve and Lake Mburo National Park [54]. The current finding is therefore an important step in improving the understanding of the species’ biogeography. Almost all the wild edible plant species in this area have uncertain conservation status (not evaluated) (Fig. 8), yet it is generally accepted that lack of suitable data for prioritizing conservation action greatly hampers plant conservation efforts [55]. However, it should be noted that some of the taxa in the not evaluated category are cosmopolitan species. Some of them are in the family Amaranthaceae which constitute most weeds and secondary crops occurring abundantly in different ecological areas. T. indica has been assessed as vulnerable by the National Red List of Uganda [56] but has not been assessed by the IUCN.

The wild edible plants in Teso-Karamoja region ultimately offer various benefits and opportunities to the dependent communities. These plants present a cheap means of enriching the diets, creating employment, and diversifying the livelihoods of rural communities in the rural communities of Teso-Karamoja region. There are already some isolated individuals and trade companies exploiting the collection of gum Arabic from Senegalia senegal (L.) Britton, shea nuts from V. paradoaxa, tamarinds from T. indica, and desert date from B. aegyptiaca. Other initiatives include making of wine from S. innocua, B. schleronuera, V. madiensis, and C. spinarum. However, the challenge is that these initiatives are highly fragmented, uncoordinated, and poorly documented, thereby preventing the realization of their full potential.

Conclusion

A high diversity of wild edible plant species in the forest reserves of Teso-Karamoja region has been established. The majority of species are natives with a limited range of exotics. Fruit consumption is the most important use category of wild edible plants in this area. All the species enumerated are considered important throughout the year because they serve different purposes. Therefore, this study has certainly made a significant contribution to the preservation of the cultural heritage in a form of wild edible plant indigenous knowledge in this region.

Recommendations

There is a need to store the documented information in user-friendly formats for access by the local communities. The development of propagation protocols for highly rated species will go along in promoting a deliberate domestication drive, thereby reducing the dependence on the wild population. It is also pertinent to elucidate the nutritional contribution of these plants to human diets and explore their role as trade-offs in forest reserve management.

References

King FB. Interpreting wild food plants in archaeological record. In: Etkin NL, editor. Eating on the wild side. Tucson: University of Arizona Press; 1994.

Ruffo CK, Birnie A, Tengnäs B. Edible wild plants of Tanzania. Regional land management unit (RELMA). Nairobi: Swedish International Development Cooperation Agency (Sida); 2002.

Egeru A, Wasonga O, Kyagulanyi J, Majaliwa GM, MacOpiyo L, Mburu J. Spatio-temporal dynamics of forage and land cover changes in Karamoja sub-region, Uganda. Pastoralism. 2014;4(1):6.

IPC. Uganda-current acute food security situation: January–March 2017. Integrated food security phase classification. 2017. http://www.ipcinfo.org/ipcinfo-website/search-result/en/?q=Uganda. Accessed 30 Mar 2017.

Pérez AA, Fernández BH, Gatti RC, editors. Building resilience to climate change: ecosystem-based adaptation and lessons from the field. London: IUCN; 2010.

Shad AA, Shah HU, Bakht J. Ethnobotanical assessment and nutritive potential of wild food plants. J Anim Plant Sci. 2013;23(1):92–7.

Msuya TS, Kideghesho JR, Mosha TC. Availability, preference, and consumption of indigenous forest foods in the Eastern Arc Mountains, Tanzania. Ecol Food Nutr. 2010;49(3):208–27.

Gockowski J, Mbazo’o J, Mbah G, Moulende TF. African traditional leafy vegetables and the urban and peri-urban poor. Food Policy. 2003;28(3):221–35.

Maroyi A. The gathering and consumption of wild edible plants in Nhema Communal Area, Midlands Province, Zimbabwe. Ecol Food Nutr. 2011;50(6):506–25.

Keegan WF. The optimal foraging analysis of horticultural production. Am Anthropol. 1986;88(1):92–105.

Moerman DE. The medicinal flora of native North America: an analysis. J Ethnopharmacol. 1991;31:1–42.

Sih A, Christensen B. Optimal diet theory: when does it work, and when and why does it fail? Anim Behav. 2001;61(2):379–90.

Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations. The state of food security and nutrition in the world 2017: building resilience for peace and food security. Rome: FAO; 2017.

Jman Redzic S. Wild edible plants and their traditional use in the human nutrition in Bosnia-Herzegovina. Ecol Food Nutr. 2006;45(3):189–232.

Harris FM, Mohammed S. Relying on nature: wild foods in northern Nigeria. AMBIO. 2003;32(1):24–9.

Bharucha Z, Pretty J. The roles and values of wild foods in agricultural systems. Philos Trans R Soc London B Biol Sci. 2010;365(1554):2913–26.

Shumsky SA, Hickey GM, Pelletier B, Johns T. Understanding the contribution of wild edible plants to rural social-ecological resilience in semi-arid Kenya. Ecol Soc. 2014;19(4).

Balemie K, Kebebew F. Ethnobotanical study of wild edible plants in Derashe and Kucha districts, South Ethiopia. J Ethnobiol Ethnomed. 2006;2:53.

Karjalainen E, Sarjala T, Raitio H. Promoting human health through forests: overview and major challenges. Environ Health Prev Med. 2010;15(1):1–8.

Bhattarai S, Chauldhary RP, Taylor RSL. Prioritization and trade of ethnobotanical plants by the people of Manang District, Central Nepal. In: Chauldhary RP, Aase TH, Vetaas OR, Subedi BP, editors. Local effects of global changes in the Himalayas. Manang, Nepal: Tribuvan University and Norway: University of Bergen; 2007. p. 151–69.

Alves RR, Rosa IM. Biodiversity, traditional medicine and public health: where do they meet? J Ethnobiol Ethnomed. 2007;3(1):14.

Tabuti JRS, Kukunda CB, Kaweesi D, Kasilo OM. Herbal medicine use in the districts of Nakapiripirit, Pallisa, Kanungu, and Mukono in Uganda. J Ethnobiol Ethnomed. 2012;8(1):1.

Bachman S, Fernandez EP, Hargreaves S, Nic Lughadha E, Rivers M, Williams E. Extinction risk and threats to plants. In: RBG Kew, state of the world’s plants report. Royal Botanic Gardens, Kew; 2016. p. 58–63.

Drichi P, National Biomass Study. Forest department, Kampala, Uganda; 2003. p. 230.

Bukenya ZR. The non-cultivated edible plants of Uganda, NAPRECA MONOGRAPH SERIES NO.9. NAPRECA: Addis Ababa; 1996. p. 60.

Katende AB, Bukenya ZR, Kakudidi EK, Lye KA. Catalogue of economically important plants in Uganda. Uganda: Botany Department, Makerere University; 1998.

Katende AB, Segawa P, Birnie A. Wild food plants and mushrooms of Uganda. Nairobi: Saida Regional Land Management Unit; 1999.

Kakudidi EK, Bukenya-Ziraba R, Kasenene JM. Wild foods from in and around Kibale National Park in Western Uganda. LIDIA Nor J Bot. 2004;6(3):65–82.

Agea JG, Okia CA, Abohassan RA, Kimondo JM, Obua J, Hall J, Teklehaimanot Z. Wild and semi-wild food plants of Bunyoro-Kitara Kingdom of Uganda: growth forms, collection niches, parts consumed, consumption patterns, main gatherers and consumers. Environ Res J. 2011;5(2):74–86.

Bortolotto IM, de Mello Amorozo MC, Neto GG, Oldeland J, Damasceno-Junior GA. Knowledge and use of wild edible plants in rural communities along Paraguay River, Pantanal, Brazil. J Ethnobiol Ethnomed. 2015;11(1):46.

FAO. Report on the state of the world’s plant genetic resources. Leipzig, Germany: International Technical Conference on Plant Genetic Resources. FAO ITCPGR/96/3; 1996. p. 17–23.

Aguilar S, Condit R. Use of native tree species by an Hispanic community in Panama. Econ Bot. 2001;55(2):223–35.

FAO. The state of food insecurity in the world. Rome: FAO; 2009.

Kalema J. Diversity and distribution of vascular plants in Uganda's wetland and dryland important bird areas. Doctoral dissertation, Ph.D. thesis. Kampala: Makerere University; 2005.

de Albuquerque UP. Re-examining hypotheses concerning the use and knowledge of medicinal plants: a study in the Caatinga vegetation of NE Brazil. J Ethnobiol Ethnomed. 2006;2(1):30.

Phillips O, Gentry AH. The useful plants of Tambopata, Peru: II. Additional hypothesis testing in quantitative ethnobotany. Econ Bot. 1993;47(1):33–43.

Alencar NL, de Sousa Araújo TA, de Amorim EL, de Albuquerque UP. The inclusion and selection of medicinal plants in traditional pharmacopoeias—evidence in support of the diversification hypothesis. Econ Bot. 2010;64(1):68–79.

NFA. Uganda’s forests, functions and classification. Kampala: National Forestry Authority (NFA); 2005. p. 36.

Egeru A. Role of indigenous knowledge in climate change adaptation: a case study of Teso sub-region, Eastern Uganda. Indian J Tradit Knowl. 2012;11(2):217–24.

Statistics YT. An introductory analysis. 2nd ed. New York: Harper and Row; 1967.

Lykke AM. Local perceptions of vegetation change and priorities for conservation of woody-savanna vegetation in Senegal. J Environ Manag. 2000;59(2):107–20.

Tardío J, Pardo-de-Santayana M. Cultural importance indices: a comparative analysis based on the useful wild plants of Southern Cantabria (Northern Spain). Econ Bot. 2008;62(1):24–39.

Trotter RT, Logan MH. Informant census: a new approach for identifying potentially effective medicinal plants. In: Etkin LN, editor. Plants in indigenous medicine and diet. Redgrave, Bedford Hill, New York; 1986. p. 91–112.

Berihun T, Molla E. Study on the diversity and use of wild edible plants in Bullen District Northwest Ethiopia. J Bot. 2017;2017:1–10.

Ogoye-Ndegwa C. Traditional gathering of wild vegetables among the luo of Western Kenya-a nutritional anthropology project1. Ecol Food Nutr. 2003;42(1):69–89.

Sansanelli S, Ferri M, Salinitro M, Tassoni A. Ethnobotanical survey of wild food plants traditionally collected and consumed in the Middle Agri Valley (Basilicata region, Southern Italy). J Ethnobiol Ethnomed. 2017;13(1):50.

Ojelel S, Kakudidi EK. Wild edible plant species utilized by a subsistence farming community in Obalanga sub-county, Amuria district, Uganda. J Ethnobiol Ethnomed. 2015;11(1):7.

Campbell BM. The use of wild fruits in Zimbabwe. Econ Bot. 1987;41:375–85.

Gragson TL. Human foraging in lowland South America: patterns and process of resource procurement. Res Econ Anthropol. 1993;14:107–38.

Tabuti JRS, Dhillion SS, Lye KA. The status of wild food plants in Bulamogi County, Uganda. Int J Food Sci Nutr. 2004;55:485–98.

Brown K, Lapuyade S. Changing gender relationships and forest use: A case study from Komassi, Cameroon, in Colfer CJP, Byron Y, editors. People managing forests: the link between human well being and sustainability, RFF, Washington, DC/CIFOR, Bogor 2002.p90–110.

Byron RN, Arnold JEM. What futures for the people of the tropical forests? World Dev. 1999;27(5):189–805.

Scoones I, Melnyk M, Pretty JN. The hidden harvest: wild foods and agricultural systems. A literature review and annotated bibliography; 1992.

Beentje HJ. Psilotrichum axilliflorum. The IUCN red list of threatened species 2017: https://doi.org/10.2305/IUCN.UK.2017-1.RLTS.T185448A84256720.en. Accessed 15 June 2018

Darbyshire I, Anderson S, Asatryan A, Byfield A, Cheek M, Clubbe C, Ghrabi Z, Harris T, Heatubun CD, Kalema J, Magassouba S. Important plant areas: revised selection criteria for a global approach to plant conservation. Biodivers Conserv. 2017;26(8):1767–800.

WCS. Nationally threatened species for Uganda. Kampala: Wildlife Conservation Society; 2016. p. 70.

Acknowledgements

The authors would like to sincerely applaud the local communities in and around the forest reserves of Teso-Karamoja region who unreservedly shared their indigenous knowledge pertaining to the use of wild edible plants. All the local council leaders and the field assistants in the respective villages around forest reserves where the ethnobotanical surveys were conducted are highly appreciated for their assistance. The staff at Makerere University Herbarium especially Mr. Protase who identified the voucher specimens is also appreciated.

Funding

This study was funded by DAAD (91636693) through a PhD scholarship awarded to SO. The equipment used in the field was donated by IDEA WILD to SO.

Availability of data and materials

All the data generated or analyzed during this study are included in the published article. The plant voucher specimens were deposited at the Makerere University Herbarium.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

SO was responsible for data collection, analysis, and drafting of the manuscript. PM, EK, and JK supervised the research and critically reviewed the draft manuscript. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate

This study was approved by the Uganda National Council for Science and Technology (UNCST/RCI/439). The research permit to the forest reserves was awarded by the National Forestry Authority (no. 284). In the community, the objectives of the study were elaborated to the respondents to enable them make an informed opinion whether to participate or not. The respondents who agreed to participate signed the consent form in the presence of a witness.

Consent for publication

Not applicable

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/), which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made. The Creative Commons Public Domain Dedication waiver (http://creativecommons.org/publicdomain/zero/1.0/) applies to the data made available in this article, unless otherwise stated.

About this article

Cite this article

Ojelel, S., Mucunguzi, P., Katuura, E. et al. Wild edible plants used by communities in and around selected forest reserves of Teso-Karamoja region, Uganda. J Ethnobiology Ethnomedicine 15, 3 (2019). https://doi.org/10.1186/s13002-018-0278-8

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/s13002-018-0278-8