Abstract

Background

Rhabdomyosarcomas are aggressive tumors that comprise a group of morphologically similar but biologically diverse lesions. Owing to its rarity, Mixed pattern RMS (ARMS and ERMS) constitutes a diagnostic and therapeutic dilemma.

Case

Herein is presented a very rare case of mixed alveolar & embryonal rhabdomyosarcoma in the uterus of a 68-year-old woman. The wall of the uterine corpus & cervix was replaced by multiple whitish–yellow, firm nodules, measuring up to 12 cm. Microscopically, the tumor was predominantly composed of round to polygonal cells arranged in nests with alveolar pattern intermingled with hypo- & hypercellular areas of more primitive cells with scattered multinucleated giant cells seen as well. Extensive sampling failed to show epithelial elements. Immunohistochemical staining showed positive staining for vimentin, desmin, myogenin, CD56 & WT-1. However, no staining was detected for CK, LCA, CD10, ER, SMA, CD99, S100, Cyclin-D1 & Olig-2. Metastatic deposits were found in the peritoneum. The patient received postoperative chemotherapy and radiotherapy but died of systemic metastases 3 months after surgery.

Conclusion

The rarity of this histological tumor entity and its aggressive behavior and poor prognosis grab attention to improving recognition and treatment modalities in adults.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Rhabdomyosarcoma (RMS) is an aggressive malignant mesenchymal tumor of striated muscle origin that is more commonly diagnosed in children and adolescents than adults [1]. It develops essentially in the deep soft tissue of the neck, extremities, and perineal region [2]. According to the World health organization (WHO) classification introduced in 2020, rhabdomyosarcoma is subclassified into four major subtypes: embryonal (ERMS), alveolar (ARMS), pleomorphic (PRMS), and spindle cell/sclerosing [3]. Primary uterine rhabdomyosarcoma can present as a heterologous differentiation in uterine carcinosarcoma or adenosarcoma or, far less commonly, arises as a pure uterine rhabdomyosarcoma [4, 5].

Primary pure rhabdomyosarcoma infrequently involves gynecological regions, where the embryonal subtype represents more than 75% of cases, especially in children with DICER1 syndrome, and is associated with favorable prognosis in comparison with ARMS and PRMS [3]. ARMS and PRMS are seen nearly exclusively in adults, with PRMS typically involving post-menopausal females [6]. Some rhabdomyosarcomas contain histologic features of multiple subtypes. In 1995, Pappo et al. reported that the presence of any alveolar element translates into a bad prognosis. [7]

The biologic basis for these mixed tumors is currently unknown, although some studies suggest that even the embryonal elements of “bad” tumors have genetic features of ARMS [8, 9].Rhabdomyosarcoma with mixed embryonal and alveolar features were previously thought to be a form of alveolar RMS, but studies have shown that most lack PAX3/7::FOXO1 fusions, suggesting that such tumors are more in line with embryonal RMS. However some mixed tumors have had detectable gene fusions which clearly would be more in keeping with alveolar RMS [10].

Owing to its rarity, there are limited data regarding frequency and clinico-pathological features of primary pure uterine rhabdomyosarcoma in publications. Therefore, the current study describes the clinicopathologic & immunohistochemical features of a new case of uterine RMS in an adult woman and also reviews the available cytological and clinicopathological findings of previously reported adult uterine RMS cases in English literature with the goal of improving recognition of this tumor outside of its classical setting.

• Case:

Material and method

Clinical data

Female patient aged 68 years presented with an abdominal mass and abnormal uterine bleeding. No specific medical or surgical history (including a history of previous radiation exposure) was reported. Imaging studies demonstrated multiple intra-luminal and intra-mural uterine masses with peritoneal deposits. The patient underwent TAH+BSO with excision of peritoneal deposits. The specimen was preserved in 10% formalin, and referred to Pathology Department Lab, Faculty of Medicine, Tanta University, Egypt. Patient's clinical data including name, age, medical and surgical history, contact information & type of operation performed were all recorded.

Gross examination

The specimen was registered, coded and underwent pathological analysis. Pathological aspects that were assessed included the tumor site, tumor size & extension. Meticulous sampling of the tumor was performed (one section for every 2 cm of the tumor). All submitted sections from the primary uterine tumor obtained from the received specimen were readily available for histopathological examination and further immunohistochemical studies. Formalin-fixed paraffin-embedded (FFPE) tissues were processed for light microscopic examination, and histological sections were stained using hematoxylin and eosin (H&E) stains. Paraffin blocks were then selected for immunohistochemical procedures.

Histopathological examination

Histopathological features which were evaluated included pattern of growth, presence of any epithelial elements, presence of other heterologous elements, cellular features, nuclear pleomorphism, mitotic activity, amount of rhabdomyoblastic cells, myometrial invasion, vascular invasion and extra-uterine extension.

Immunohistochemistry

Immunohistochemical studies were performed on FFPE selected blocks from the tumor. The (FFPE) blocks were sectioned (5 µm thick) on positively charged slides and were dried for 30 min at 37°C. The slides were placed in Dako PT Link unit for deparaffinization and antigen retrieval. EnVisionTM FLEX Target Retrieval Solution with a high pH was used at 97°C for 20 minutes. Immunohistochemistry was performed using Dako Autostainer Link 48. For 10 minutes, slides were immersed in Peroxidase-Blocking Reagent, incubated with primary antibodies utilized in this study (summarized in Table 1). Following that, the slides were treated for 20 minutes with horseradish peroxidase polymer reagent and 10 minutes with diaminobenzidine chromogen. After that, the slides were counterstained with hematoxylin.

Follow up data

Clinical & follow up information were all obtained from patient medical record and by contacting the referring physician & patient family as well.

Literature review

A systematic review of the English-language literature since 1972 for “primary uterine rhabdomyosarcoma” in adults above 30 years of age was conducted.

Results

Gross examination

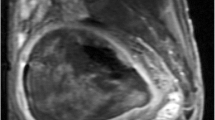

The uterine corpus was cut open when received, measured 18x18x15 cm, and revealed multiple pale spherical firm transmural nodules infiltrating the myometrium and encroaching the perimetrium. Meanwhile, some of these nodules were seen protruding into the uterine cavity. The largest nodule measured 12x7 cm and was centered in the myometrium. All nodules were fleshy, white yellow and homogenous (Figure 1a, b), yet no gross necrosis was seen. The cervical stump was received as a separate specimen measured 9x7x7 cm and showed almost total infiltration by similar nodules. Both ovaries & fallopian tubes were included with each ovary measured about 4x2x1 cm and each tube length was about 7 cm with no remarkable findings. Excised fragmented peritoneal fat measured collectively about 5x3 cm and was studded with metastatic deposits that exhibited similar gross features to the uterine ones.

Microscopic examination

H&E-stained sections obtained from tumor nodules demonstrated, interestingly, the tumor exhibiting mixed patterns; while the majority of malignant cells were arranged in nests with loss of cellular cohesion in the center giving alveolar pattern, and separated by fibrovascular septa, other areas demonstrating alternating hypo- and hypercellularity within myxoid background with perivascular and sub-epithelial condensation were seen as well. Alveolar areas showed primitive mesenchymal malignant cells with various stages of myogenic differentiation. The tumor cells were mix of medium and large sized, round undifferentiated cells together with differentiating rhabdomyoblastic cells showing eccentric nuclei, frequently with prominent nucleoli, and abundant polygonal eosinophilic cytoplasm with notable cross striations. Other areas were formed of primitive small and medium sized mesenchymal cells that showed lesser degree of striated muscle differentiation with frequent anaplastic cells showing large hyperchromatic nuclei with frequent mitosis. Besides, solid and densely cellular areas showing aggregates of pleomorphic cells with bizarre-looking nuclei and multinucleated tumor giant cells were seen.

The tumor was diffusely infiltrating uterine wall (corpus and cervical stump), dissecting the myometrium up to serosa. Although scarce entrapped benign endometrial and endocervical glands were encountered, no malignant epithelial component was detected (the tumor was re-sectioned and thoroughly examined to ensure absence of any neoplastic epithelial element whether adenomatous or carcinomatous). Frequent lymphovascular and perineural invasion was seen together with infiltration of peritoneal fat. Figure 2 (a-l) demonstrates different histopathological features of studied case.

Microscopic examination of studied uterine rhabdomyosarcoma case showing mixed patterns; nests of malignant cells with alveolar pattern (a), hypo- and hypercellular areas (b) Alveolar areas showing medium and large sized, round undifferentiated cells together with differentiating rhabdomyoblastic cells (c), other areas formed of primitive small and medium sized mesenchymal cells frequent anaplastic cells & frequent mitosis (d), solid densely cellular areas showing microscopic necrosis, pleomorphic cells with bizarre-looking nuclei and multinucleated tumor giant cells (e &f). The tumor was diffusely infiltrating uterine wall with entrapment of benign endometrial glands (g, h), showing lymphovascular emboli (i), with perivascular arrangement of tumor cells (j) infiltration of cervix (k) & peritoneal fat (l). [Hematoxylin & Eosin (a, e, k, l ) X 100; (c, d &f X 400); (b, g, h, i, j X 200)]

Immunohistochemistry

Both vimentin and desmin showed diffuse heterogeneous strong positive cytoplasmic staining (Figure 3: a-d). Also, myogenin showed heterogeneous positive nuclear staining but of moderate-intensity with accentuation in alveolar areas and rhabdomyoblastic cells (Figure 3: e, f). Tumor cells showed membranous positivity for CD56 & cytoplasmic positivity for WT-1 (Figure 3: g-j). SMA, CD10, ER, cyclin D1, CD99, S100, and LCA were all negative. No malignant epithelial element was distinguished with pan cytokeratin or ER. OLIG2 was negative as well.

Follow up data

The patient received postoperative chemotherapy and radiotherapy but died because of complications of systemic metastases 3 months after surgery.

Diagnosis and tumour stage

The final diagnosis was primary uterine rhabdomyosarcoma with mixed pattern (embryonal and alveolar). Based on the TNM staging system for uterine sarcoma endorsed by the American Joint Committee on Cancer (AJCC) and the parallel system formulated by the International Federation of Gynecology and Obstetrics (FIGO) 2018 update [11], Tumour stage was pT2NxM1, Stage Group & FIGO Stage IVB.

Literature review

The reported cases retrieved by systematic review were summarized and tabulated in a chronological manner (Table 2).

Discussion

The current study handled a very rare and interesting case of a primary uterine mixed embryonal and alveolar type rhabdomyosarcoma involving both uterine corpus and cervix in a 68-year old woman, which provided an opportunity to enlighten different aspects regarding the diagnosis and differential diagnosis of primary uterine RMS as well as better understanding of RMS classification and characteristics of each subtype by surveying recent related publications.

The systematic review of the English-language literature that focused on primary uterine rhabdomyosarcoma in adults above 30 years of age uncovered 87 cases between 1972 and 2023. Recorded available variables, including age, RMS type, tumor size/weight, treatment methods, and follow-up are shown in Table 2. To our knowledge this is the broadest literature review collection of such rare cases.

Mixed pattern RMS (ARMS and ERMS) constitutes a diagnostic dilemma regarding its histopathological features. Whereas some confusion may easily occur between ARMS cases that show solid areas reminiscent of ERMS and ERMS cases with dense pattern that may resemble solid ARMS, the truly histologically mixed pattern rhabdomyosarcomas are rare tumors and applied only for selected cases. These tumors exhibit separate, discrete ARMS and ERMS morphology with variable extent of each component [49]. Originally, it was sufficient to establish the diagnosis of ARMS if any focus of alveolar morphology was identified, and tumors that exhibit discrete areas of both alveolar and embryonal histology "of any histologic pattern of ERMS” were diagnosed as ARMS [50, 51].

In cases of malignant mesenchymal tumor in the uterus, extensive sampling is necessary to exclude sarcomatous overgrowth in adenosarcoma or carcinosarcoma[51, 52]. Adenosarcoma is generally characterized by broad leaf-like or club-like projections[53]. In the present case, extensive sampling of surgical specimen and cytokeratin immunostaining failed to reveal the presence of any neoplastic epithelial elements, leading to the adenosarcoma and carcinosarcoma diagnoses being ruled out.

The tumor cells were immunohistochemically positive for vimentin, also they were positive for striated muscle markers, such as desmin & myogenin but negative for SMA. These findings were similar to those reported by others [39]. Expressions of both desmin & myogenin are reciprocally related to the degree of cellular differentiation, thus more myogenin staining is seen in primitive-appearing cells and a decreased or absence of immunoreactivity is seen in large differentiated rhabdomyoblasts and the opposite reported for desmin [54].

Endometrial stromal sarcoma was excluded in this case by negative immunostaining to CD10, ER, CD99, and Cyclin-D1 primary antibodies. WT-1 showed only cytoplasmic staining with absent nuclear staining, supporting the idea that tumors with this phenotype exhibit WT1 deregulation. The immunohistochemical results were in line with previous findings that WT-1 protein is not acting as a nuclear transcription factor in such tumors but instead is stabilized in the cytoplasm [55].

CD56 showed membranous staining in tumor cells, which is a sensitive marker of poorly differentiated neuroendocrine carcinomas. However, the results highlight the lack of specificity of this antibody, especially in clinical situations where small cell carcinoma is suspected. Moreover, Bahrami et al., reported in 2008 that it may also be expressed in almost all other small round cell neoplasms [56]. Results of CD56 expression in current case are in keeping with these prior findings.

One of the important implications of findings in presented case was recognition that ARMS can display a wide immunophenotypical spectrum, and this grabbed attention to avoid misdiagnosis of this tumor as it morphologically can resembles other small round cell tumors.

The histogenesis of rhabdomyosarcomatous differentiation in uterine RMS is not fully understood, but it could arise from primitive or uncommitted mesenchymal cells that undergo rhabdomyosarcomatous differentiation. An alternative theory suggests that uterine RMS represents sarcomatous overgrowth in adenosarcoma or carcinosarcoma, although this would be difficult to prove in practice [57].

The chromosomal translocations t(2;13)(q35;q14) and t(1;13)(p36;q14) are characteristic of soft tissue alveolar rhabdomyosarcoma. Molecular classification has been proposed, dividing RMS into two basic groups: fusion-positive RMS (either PAX7::FOXO1 enriched or PAX3::FOXO1 enriched) and fusion negative RMS (which is further sub-divided into well differentiated RMS, moderately differentiated RMS, and undifferentiated sarcomas) [58]. ERMS and PRMS are typically fusion negative. Whereas ARMS with t(2;13) & PAX3::FOXO1 translocations has a worse prognosis compared to PAX7::FOXO1 and fusion negative cases of ARMS [59]. Recent publications reported that the remaining fraction of fusion-negative ARMS have a clinical and biological behavior similar to ERMS[60].

The fusion status of RMS with mixed patterns is heterogeneous among different publications, but the majority of reported cases are fusion-negative [58]. It is believed that fusion status for all cases of RMS, including RMS with mixed-pattern, should be investigated since it carries a prognostic value. Several studies have examined gene expression differences in fusion-driven RMS compared to its fusion-negative counterpart,as well as their relation to myogenin expression status, and reported that strong and diffuse expression of myogenin is closely associated with the presence of PAX3/7::FOXO1 translocations [61,62,63]. Kaleta et al., in 2019 concluded that immunohistochemical expression of OLIG2 may function as a surrogate marker for the presence of PAX3/7::FOXO1 translocation in RMS [64]. The current case showed no evidence of OLIG2 immunohistochemical staining and heterogeneous expression of myogenin, possibly denoting fusion negativity. One of the shortages of this study is that genetic analysis was not performed, and thus we emphasize on the importance of molecular testing for accurate categorization and better predilection of the tumor behavior.

Rhabdomyosarcoma arising in the uterus has been fairly reported. In 1909, Robertsondescribed the first case of uterine rhabdomyosarcoma in English literature, where an alveolar architecture for the tumor was portrayed [65]. Nevertheless, mixed rhabdomyosarcoma of the alveolar and embryonal types is very rare. To the best of our knowledge, besides the present case, only Gottwald et al., in 2008, reported such case. They reported that she had previous history of breast carcinoma, and interestingly, was diagnosed with both uterine RMS and Gastric GIST while receiving adjuvant hormonal therapy for breast cancer [30]. The present case had no past medical history, yet pursued a very aggressive clinical course and died 3 months after surgery because of complications of systemic metastasis,despite receiving postoperative chemotherapy and radiotherapy.

Conclusion

Summing up, the above-described clinical case of rhabdomyosarcoma with mixed alveolar & embryonal patterns of adult uterus is a very rare malignant tumor. Its diagnosis is based on histopathological analysis and confirmed by immunohistochemical examination. Clinical symptoms are non-specific for these cases. The rarity of this histological entity and protocol applied make the presented case worthy to shed light on. Moreover, despite comprehensive treatment, it is an aggressive tumor with poor prognosis and thus further molecular studies & research are needed to improve therapy options in adults.

Ethical statement

Approval for a study protocol was not required because this was a case report with literature review. The authors have obtained the patient’s written informed consent for print and electronic publication of this case report.

Availability of data and materials

No datasets were generated or analysed during the current study.

Abbreviations

- RMS:

-

Rhabdomyosarcoma

- ERMS:

-

Embryonal rhabdomyosarcoma

- ARMS:

-

Alveolar rhabdomyosarcoma

- PRMS:

-

Pleomorphic rhabdomyosarcoma

- LMS:

-

Leiomyosarcoma

- ESS:

-

Endometrial stromal sarcoma

- WHO :

-

World Health Organization

- TNM:

-

Tumor (T), nodes (N), and metastases (M)

- AJCC:

-

American Joint Committee on Cancer

- FIGO:

-

The International Federation of Gynecology and Obstetrics

- FFPE:

-

Formalin-fixed paraffin-embedded

- H and E:

-

Heamatoxylin and eosin

- TAH :

-

Total abdominal hysterectomy

- SH :

-

Simple hysterectomy

- sTH:

-

Subtotal hysterectomy

- TH :

-

Total hysterectomy

- AH:

-

Abdominal hysterectomy

- RH:

-

Radical hysterectomy

- Lt S:

-

Left salpingectomy

- PPLND :

-

Pelvic and paraaortic L.N dissection

- PLND:

-

Pelvic L.N dissection

- Lt PPLND :

-

Left pelvic and paraaortic L.N dissection

- Rt PLND:

-

Right pelvic L.N dissection

- O:

-

Omentectomy

- adj :

-

Adjuvant

- neoadj :

-

Neoadjuvant

- RT :

-

Radiotherapy

- CT:

-

Chemotherapy

- BSO:

-

Bilateral salpingo-oophorectomy

- BO:

-

Bilateral oophorectomy

- Lt SO:

-

Left salpingo-oophorectomy

- DOD :

-

Death of disease

- AWD:

-

Alive with disease

- F/U:

-

Follow up

References

Dasgupta R, Fuchs J, Rodeberg D. Rhabdomyosarcoma. Semin Pediatr Surg. 2016;25(5):276–83. https://doi.org/10.1053/j.sempedsurg.2016.09.011.

Nishino S, Shimizu Y, Yamashita D, et al. Primary alveolar rhabdomyosarcoma of the uterine corpus expressing MUC4 and OLIG2: a case report with combined morphological and molecular analysis. Hum Pathology Reports. 2022;28:300637. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.hpr.2022.3006371.

WHO Classification of Tumors Editorial Board, World Health Organization classification of tumors, the female genital tumors. 5th ed. Lyon: IARC Press; 2020. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.hpr.2022.300637.

Pinto A, Kahn RM, Rosenberg AE, et al. Uterine rhabdomyosarcoma in adults. Hum Pathol. 2018;74:122–8. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.humpath.2018.01.007.

Ashley CW, Da Cruz Paula A, Ferrando L, et al. Genetic characterisation of adult primary pleomorphic uterine rhabdomyosarcoma and comparison with uterine carcinosarcoma. Histopathol. 2021;79(2):176–86. https://doi.org/10.1111/his.14346.

Li ZJ, Li CL, Wang W, et al. Diagnosis and treatment of pleomorphic rhabdomyosarcoma of the uterus: a rare case report and review of the literature. J Int Med Res. 2021;49(5):030006052110143. https://doi.org/10.1177/03000605211014360.

Pappo AS, Shapiro DN, Crist WM, et al. Biology and therapy of pediatric rhabdomyosarcoma. J Clin Oncol. 1995;13:2123–39. https://doi.org/10.1200/JCO.1995.13.8.2123.

Anderson J, Renshaw J, McManus A, et al. Amplification of the t(2;13) and t(1;13) translocations of alveolar rhabdomyosarcoma in small formalin-fixed biopsies using a modified reverse transcriptase polymerase chain reaction. Am J Pathol. 1997;150:477–82 (PMCID: PMC1858277).

Tobar A, Avigad S, Zoldan M, et al. Clinical relevance of molecular diagnosis in childhood rhabdomyosarcoma. Diagn Mol Pathol. 2000;9:9–13. https://doi.org/10.1097/00019606-200003000-00002.

Arnold MA, Anderson JR, Gastier-Foster JM, et al. Histology, fusion status, and outcome in alveolar rhabdomyosarcoma with low-risk clinical features: a report from the Children’s Oncology Group. Pediatr Blood Cancer. 2016;63(4):634–9. https://doi.org/10.1002/pbc.25862.

Amin MB, Greene FL, Edge SB, et al. The eighth edition AJCC cancer staging manual: continuing to build a bridge from a population-based to a more “personalized” approach to cancer staging. CA Cancer J Clin. 2017;67(2):93–9.

Donkers B, Kazzaz BA, Meijering JH. Rhabdomyosarcoma of the corpus uteri. Report of two cases with review of the literature. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 1972;114:1025–30. https://doi.org/10.1016/0002-9378(72)90863-0.

Hart WR, Craig JR. Rhabdomyosarcomas of the Uterus. Am J Clin Pathol. 1978;70(2):217–23. https://doi.org/10.1093/ajcp/70.2.217.

Vakiani M, Mawad J, Talerman A. Heterologous sarcomas of the uterus. Int J Gynecol Pathol. 1982;1:211–9. https://doi.org/10.1097/00004347-198202000-00008.

Siegal GP, Taylor LL III, Nelson KG, et al. Characterization of a pure heterologous sarcoma of the uterus: rhabdomyosarcoma of the corpus. Int J Gynecol Pathol. 1983;2:303–15. https://doi.org/10.1097/00004347-198303000-00008.

Jaworski RC, Rencoret RH, Moir DH. Pleomorphic rhabdomyosarcoma of the uterus. Case report with a review of the literature. Br J Obstet Gynaecol. 1984;91:1269–73. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1471-0528.1984.tb04750.x.

Montag TW, D’ablaing G, Schlaerth JB, et al. Embryonal rhabdomyosarcoma of the uterine corpus and cervix. Gynecol Oncol. 1986;25(2):171–94. https://doi.org/10.1016/0090-8258(86)90098-3.

Podczaski E, Sees J, Kaminski P, et al. Rhabdomyosarcoma of the uterus in a postmenopausal patient. Gynecol Oncol. 1990;37:439–42. https://doi.org/10.1016/0090-8258(90)90384-w.

Emerich J, Senkus E, Konefka T. Alveolar rhabdomyosarcoma of the uterine cervix. Gynecol Oncol. 1996;63:393–403. https://doi.org/10.1006/gyno.1996.0343.

Chiarle R, Godio L, Fusi D, et al. Pure alveolar rhabdomyosarcoma of the corpus uteri: description of a case with increased serum level of CA-125. Gynecol Oncol. 1997;66(2):320–3. https://doi.org/10.1006/gyno.1997.4742.

Ordi J, Stamatakos MD, Tavassoli FA. Pure pleomorphic rhabdomyosarcomas of the uterus. Int J Gynecol Pathol. 1997;16(4):369–77. https://doi.org/10.1097/00004347-199710000-00013.

Holcomb K, Francis M, Ruiz J, et al. Pleomorphic rhabdomyosarcoma of the uterus in a postmenopausal woman with elevated serum CA125. Gynecol Oncol. 1999;74(3):499–501. https://doi.org/10.1006/gyno.1999.5460.

Okada DH, Rowland JB, Petrovic LM. Uterine pleomorphic rhabdomyosarcoma in a patient receiving tamoxifen therapy. Gynecol Oncol. 1999;75:509–13. https://doi.org/10.1006/gyno.1999.5604.

Takano M, Kikuchi Y, Aida S, et al. Embryonal rhabdomyosarcoma of the uterine corpus in a 76-year-old patient. Gynecol Oncol. 1999;75(3):490–4. https://doi.org/10.1006/gyno.1999.5593.

Mccluggage WG, Lioe TF, Mcclelland HR, et al. Rhabdomyosarcoma of the uterus: report of two cases, including one of the spindle cell variant. Int J Gynecol Cancer. 2002;12(1):128–32. https://doi.org/10.1046/j.1525-1438.2002.01069.x.

Ng TY, Loo KT, Leung TW, et al. Alveolar rhabdomyosarcoma of the cervix. Gynecol Oncol. 2003;91:623–6. https://doi.org/10.1016/s0090-8258(03)00252-x.

Borka K, Patai K, Rendek A, et al. Pleomorphic rhabdomyosarcoma of the uterus in a postmenopausal patient. Pathol Oncol Res. 2006;12(2):102–4. https://doi.org/10.1007/BF02893452.

Reynolds EA, Logani S, Moller K, et al. Embryonal rhabdomyosarcoma of the uterus in a postmenopausal woman. Case report and review of the literature. Gynecol Oncol. 2006;103(2):736–9. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ygyno.2006.03.033.

Ferguson SE, Gerald W, Barakat RR, et al. Clinicopathologic features of rhabdomyosarcoma of gynecologic origin in adults. Am J Surg Pathol. 2007;31(3):382–9. https://doi.org/10.1097/01.pas.0000213352.87885.75.

Gottwald L, Góra E, Korczyński J, et al. Primary uterine rhabdomyosarcoma in a patient with a history of breast cancer and gastrointestinal stromal tumor. J Obstet Gynaecol. 2008;34:721–5. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1447-0756.2008.00915.x.

Rivasi F, Boticelli L, Bettelli SR, et al. Alveolar rhabdomyosarcoma of the uterine cervix. A case report confirmed by FKR break-apart rearrangement using a fluorescence in situ hybridization probe on paraffin-embedded tissues. Int J Gynecol Pathol. 2008;27:442–6. https://doi.org/10.1097/PGP.0b013e31816085ce.

Yeasmin S, Nakayama K, Oride A, et al. A case of extremely chemoresistant pure pleomorphic rhabdomyosarcoma of the uterus associated with a high serum LDH level. Eur J Gynaecol Oncol. 2008;29:518–22 (PMID: 19051826).

Leung F, Terzibachian JJ, Govyadovskiy A, et al. Postmenopausal pure rhabdomyosarcoma of the uterine corpus associated with previous pelvic irradiation. Arch Gynecol Obstet. 2009;279:209–11. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00404-008-0670-z.

Chmaj-Wierzchowska K, Wierzchowski M, Szymanowski K, et al. Pleomorphic rhabdomyosarcoma of the uterine corpus–a case report. Ginekol Pol. 2010;81(7):541–3 (PMID: 20825058).

Fadare O, Bonvicino A, Martel M, et al. Pleomorphic rhabdomyosarcoma of the uterine corpus: a clinicopathologic study of 4 cases and a review of the literature. Int J Gynecol Pathol. 2010;29(2):122–34. https://doi.org/10.1097/PGP.0b013e3181bc98c0.

Fukunaga M. Pure alveolar rhabdomyosarcoma of the uterine corpus. Pathol Int. 2011;61:377–81. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1440-1827.2011.02672.x.

Kriseman ML, Wang WL, Sullinger J, et al. Rhabdomyosarcoma of the cervix in adult women and younger patients. Gynecol Oncol. 2012;126(3):351–6. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ygyno.2012.05.008.

Kim DW, Shin JH, Lee HJ, et al. Spindle cell rhabdomyosacoma of uterus: a case study. Korean J Pathol. 2013;47(4):388–91. https://doi.org/10.4132/KoreanJPathol.2013.47.4.388.

Li RF, Gupta M, McCluggage WG, et al. Embryonal rhabdomyosarcoma (botryoid type) of the uterine corpus and cervix in adult women: report of a case series and review of the literature. Am J Surg Pathol. 2013;37:344–55. https://doi.org/10.1097/PAS.0b013e31826e0271.

Kuroki M, Yoneyama K, Watanabe A, et al. Rhabdomyosarcoma of the uterus: a case report. J Nippon Med Sch. 2015;82(5):218–9. https://doi.org/10.1272/jnms.82.218.

Yamada S, Harada Y, Noguchi H, et al. Embryonal rhabdomyosarcoma arising from the uterine corpus in a postmenopausal female: a surgical case challenging the genuine diagnosis on a cytology specimen. Diagn Pathol. 2016;11:3. https://doi.org/10.1186/s13000-016-0451-0.

Alavi S, Eckes L, Kratschell R, et al. Pleomorphic rhabdomyosarcoma of the uterus - case report and a systematic review of the literature. Anticancer Res. 2017;37(5):2509–14. https://doi.org/10.21873/anticanres.11592.

Motoda N, Nakamura Y, Kuroki M, et al. Exfoliation of alveolar rhabdomyosarcoma cells in the ascites of a 50-year-old woman: diagnostic challenges and literature review. J Nippon Med Sch. 2019;86(4):236–41. https://doi.org/10.1272/jnms.JNMS.2018_86-404.

Aljehani AM, Abu-Zaid A, Alomar O, et al. Primary uterine rhabdomyosarcoma in a 54-year-old postmenopausal woman. Cureus. 2020;12(8): e9841. https://doi.org/10.7759/cureus.9841.

Aminimoghaddam S, Rahbari A, Pourali R. Rhabdomyosarcoma of the uterus in an adult patient with osteopetrosis: a case report. J Med Case Rep. 2021;15(1):570. https://doi.org/10.1186/s13256-021-03172-y.

Choi H, Lee H, Kim HS, et al. Uterine alveolar rhabdomyosarcoma in an elderly patient manifesting extremely poor prognosis; a rare subtype of rhabdomyosarcoma. Obstet Gynecol Sci. 2021;64(2):234–8. https://doi.org/10.5468/ogs.20127.

Tamura S, Hayashi T, Ichimura T, et al. Characteristic of uterine rhabdomyosarcoma by algorithm of potential biomarkers for uterine mesenchymal tumor. Curr Oncol. 2022;29(4):2350–63. https://doi.org/10.3390/curroncol29040190.

Kamboj M, Kumar A, Sharma A, et al. Pleomorphic rhabdomyosarcoma of uterus in an adult female: a rare entity. Indian J Gynecol Oncol. 2023;21:18. https://doi.org/10.1007/s40944-022-00691-4.

Rudzinski ER. Histology and fusion status in rhabdomyosarcoma. Am Soc Clin Oncol Educ Book. 2013;33:425–8. https://doi.org/10.14694/EdBook_AM.2013.33.425.

Newton WA Jr, Gehan EA, Webber BL, et al. Classification of rhabdomyosarcomas and related sarcomas. Pathologic aspects and proposal for a new classification--an intergroup rhabdomyosarcoma study. Cancer. 1995;76(6):1073–85. https://doi.org/10.1002/10970142(19950915)76:6<1073::AIDCNCR2820760624>3.0.CO;2-L.

Arndt CA, Stoner JA, Hawkins DS, et al. Vincristine, actinomycin, and cyclophosphamide compared with vincristine, actinomycin, and cyclophosphamide alternating with vincristine, topotecan, and cyclophosphamide for intermediate-risk rhabdomyosarcoma: children’s oncology group study D9803. J Clin Oncol. 2009;27(31):5182–8. https://doi.org/10.1200/JCO.2009.22.3768.

Lee CH, Nucci MR. Endometrial stromal sarcoma–the new genetic paradigm. Histopathol. 2015;67(1):1–19. https://doi.org/10.1111/his.12594.

Zhan H, Chen F, Huang Y. Uterine malignant mixed mullerian tumor: review of recent literature. N Am J Med Sci. 2017;10(3):110–5. https://doi.org/10.7156/najms.2017.1003110].

Morotti RA, Nicol KK, Parhm DM, et al. An immunohistochemical algorithm to facilitated diagnosis and subtype of rhabdomyosarcoma the Children’s Oncology Group experience. Am J Surg Pathol. 2006;30:962–8. https://doi.org/10.1097/00000478-200608000-00005.

Carpentieri DF, Nichols K, Chou PM, et al. The expression of WT1 in the differentiation of rhabdomyosarcoma from other pediatric small round blue cell tumors. Mod Pathol. 2002;15(10):1080–6. https://doi.org/10.1097/01.MP.0000028646.03760.6B.

Bahrami A, Gown AM, Baird GS, et al. Aberrant expression of epithelial and neuroendocrine markers in alveolar rhabdomyosarcoma: a potentially serious diagnostic pitfall. Mod Pathol. 2008;21(7):795–806. https://doi.org/10.1038/modpathol.2008.86.

Shintaku M, Sekiyama K. Leiomyosarcoma of the uterus with focal rhabdomyosarcomatous differentiation. Int J Gynecol Pathol. 2004;23(2):188–92. https://doi.org/10.1097/00004347-200404000-00016.

Parham DM, Barr FG. Classification of rhabdomyosarcoma and its molecular basis. Adv Anat Pathol. 2013;20(6):387–97. https://doi.org/10.1097/PAP.0b013e3182a92d0d.

Missiaglia E, Williamson D, Chisholm J, et al. PAX3/FOXO1 fusion gene status is the key prognostic molecular marker in rhabdomyosarcoma and significantly improves current risk stratification. J Clin Oncol. 2012;30(14):1670–7. https://doi.org/10.1200/JCO.2011.38.5591.

Skapek SX, Ferrari A, Gupta AA, et al. Rhabdomyosarcoma. Nat Rev Dis Primers. 2019;5(1):1. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41572-018-0051-2.

Rudzinski ER, Anderson JR, Lyden ER, et al. Myogenin, AP2β, NOS-1, and HMGA2 are surrogate markers of fusion status in rhabdomyosarcoma: a report from the soft tissue sarcoma committee of the children’s oncology group. Am J Surg Pathol. 2014;38:654–9. https://doi.org/10.1097/PAS.0000000000000195.

Dias P, Chen B, Dilday B, et al. Strong immunostaining for myogenin in rhabdomyosarcoma is significantly associated with tumors of the alveolar subclass. Am J Pathol. 2000;156:399–408. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0002-9440(10)64743-8.

Hostein I, Andraud-Fregeville M, Guillou L, et al. Rhabdomyosarcoma: value of myogenin expression analysis and molecular testing in diagnosing the alveolar subtype: an analysis of 109 paraffin-embedded specimens. Cancer. 2004;101:2817–24. https://doi.org/10.1002/cncr.20711.

Kaleta M, Wakulińska A, Karkucińska-Więckowska A, et al. OLIG2 is a novel immunohistochemical marker associated with the presence of PAX3/7-FOXO1 translocation in rhabdomyosarcomas. Diagn Pathol. 2019;14(1):10. https://doi.org/10.1186/s13000-019-0883-4.

Robertson AR. Rhabdomyosarcoma of the uterus; with the report of a case. J Med Res. 1909;20(3):297-310.1 (PMCID: PMC2099376).

Funding

Open access funding provided by The Science, Technology & Innovation Funding Authority (STDF) in cooperation with The Egyptian Knowledge Bank (EKB).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Nehal Kamel: conceptualization, methodology, investigation, resources, visualization, writing original draft and project administration; Eiman Hasby: resources, visualization, writing original draft, reviewing and supervision.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interest.

Additional information

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/. The Creative Commons Public Domain Dedication waiver (http://creativecommons.org/publicdomain/zero/1.0/) applies to the data made available in this article, unless otherwise stated in a credit line to the data.

About this article

Cite this article

Kamel, N.K., Hasby, E.A. A rare adult case of primary uterine rhabdomyosarcoma with mixed pattern: a clinicopathological & immunohistochemical study with literature review. Diagn Pathol 19, 98 (2024). https://doi.org/10.1186/s13000-024-01518-w

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/s13000-024-01518-w