Abstract

Background

Adenosquamous carcinoma (ADSC) of the lung, a rare but aggressive subtype of non-small cell lung cancer (NSCLC), is defined as a carcinoma containing components of adenocarcinoma (ADC) and squamous cell carcinoma (SqCC). Mutations of epidermal growth factor receptor (EGFR) are found at a frequency of 15 to 44% in Asian ADSC, and EGFR tyrosine kinase inhibitors (EGFR-TKIs) are a more effective treatment for EGFR-mutated ADSC compared to chemotherapy. However, ADSC in small lung biopsies could be misdiagnosed as SqCC or non-small cell carcinoma (NSCC) favor SqCC due to undersampling, which may result in neglecting of EGFR mutation testing and affecting patients’ clinical management, particularly in Asian patients that relatively have high prevalence of EGFR mutation.

Methods

A total of 148 small lung biopsy cases with pathological diagnosis of SqCC or NSCC favor SqCC were retrospectively enrolled. The frequency of EGFR mutations and the correlation between patients’ EGFR mutation status and clinicopathological characteristics were evaluated.

Results

EGFR mutations were found in 8.8% (13 /148) of all cases with 5.2% (7/135) in SqCC and 46.2% (6/13) in NSCC favor SqCC. There were 7 (53.8%) L858R mutation, 4 (30.8%) exon 19 deletions, and 2 (15.4%) cases with coexistent L858R and T790 M mutations. Multivariate analysis showed that EGFR mutations were more prevalent in never-smokers (83.3% versus 16.7%, p = 0.006) and patients diagnosed as NSCC favor SqCC (46.2% versus 5.2%, p = 0.001). Moreover, 75% (3/4) of EGFR mutation-positive cases with subsequent surgical resection or rebiopsy were further diagnosed as ADSC.

Conclusions

EGFR mutation testing should be performed in Asian patients with SqCC diagnosed from small lung biopsies, especially in never-smokers and patients with diagnosis of NSCC favor SqCC, which have a high probability of being ADSC.

Similar content being viewed by others

Background

Lung cancer is the most common cause of cancer-related death worldwide. Non-small cell lung cancer (NSCLC), accounting for approximately 80–85% of all the cases, is further divided into major histological subtypes including adenocarcinoma (ADC), squamous cell carcinoma (SqCC), large cell carcinoma (LCC), and other rare tumors including adenosquamous carcinoma (ADSC) [1]. ADSC is a rare and mixed-type NSCLC, counting for only 0.4 to 4% of all the cases. According to the World Health Organization (WHO) Classification of Lung Tumors, ADSC is defined as “a carcinoma showing components of both SqCC and ADC, with each comprising at least 10% of the tumor” [2]. ADSC has a more aggressive behavior and worse prognosis than ADC and SqCC [3, 4]. The treatment of early-stage ADSC mainly includes surgery, supplemented by chemotherapy, and other comprehensive treatment, but the curative effect is not satisfied [5]. The poor prognosis of ADSC has raised the demand for more effective treatment approaches such as targeted therapy. Recently, the development of targeted therapy toward oncogenic “driver mutations” has revolutionized the clinical management of patients with NSCLC including ADSC [6, 7].

Epidermal growth factor receptor (EGFR) mutation is the most well-characterized driver mutation in NSCLC, and is more prevalent in Asian population, never smokers, and patients with ADC subtype [8]. More than 60% of Asian ADC patients were found to have EGFR mutations [9]. EGFR tyrosine kinase inhibitors (EGFR-TKIs), giving higher response rates, longer progression-free survival and better quality of life compared to conventional chemotherapy, are now recommended as the first-line treatment in patients with advanced EGFR activating mutation-positive NSCLC [10,11,12,13]. Currently, studies demonstrated that EGFR mutations occur at a frequency of 15 to 44% in Asian ADSC and are mainly in female and never smokers; patients with ADSC showed a similar benefit from EGFR-TKI treatment compared to those with ADC, revealing that EGFR-TKI may be a therapeutic option for ADSC patients [14,15,16,17,18]. In view of this, the current guidelines recommend that EGFR mutation testing should be performed in NSCLC patients with ADC or mixed-type tumors containing an adenocarcinomatous component, for example, ADSC, and is not necessary for patients with tumors lack of any adenocarcinomatous component, such as pure SqCC or pure LCC [19, 20].

In clinical practice, accurate diagnosis of ADSC can only be made in resection specimens, because a minimum of 10% of each ADC or SqCC component is required. However, approximately 70% of lung cancer patients are diagnosed at advanced stages that are not amenable to surgical resection and small biopsies are the major tissue resources for pathological diagnosis and subtyping [21, 22]. Diagnosis of ADSC before surgical resection is not possible, since tumors present in small biopsy specimens may come from either ADC or SqCC component only. In the majority of cases, ADSC in small biopsy specimens is misdiagnosed as SqCC or poorly differentiated SqCC referring to non-small cell carcinoma (NSCC) favor SqCC due to biased sampling of the lesion, which may cause the neglect of EGFR mutation testing in these cases. A previous report by Rekhtman et al. also suggested that EGFR or KRAS mutations do not occur in pure pulmonary SqCC, and the occasional detection of these mutations may come from the challenge of ADSC diagnosis in small biopsies [23]. Furthermore, two NSCLC cases, possibly ADSC, presented by Saini et al. were initially diagnosed as SqCC in small biopsies, positive for EGFR mutations and benefitted with oral EGFR-TKI treatment [24]. The lack of EGFR mutation testing in patients who are diagnosed as SqCC from small biopsies may influence the treatment strategies for patients, especially in Asian population which has a high frequency of EGFR mutations. For this reason, we conducted an Asian retrospective study investigating the frequency and clinicopathological association of EGFR mutations in patients diagnosed as SqCC in small lung biopsies to evaluate the necessity and clinical impact of EGFR mutation testing on possibly under-sampled ADSC.

Methods

Patients

From 2007 to 2016 at Taipei Veterans General Hospital, patients with a diagnosis of SqCC or NSCC favor SqCC derived from small lung biopsies and without previous history of any carcinoma elsewhere in the body were evaluated in this retrospective study. Each case was reviewed by two independent pathologists, and all final diagnoses were made according to the 2015 WHO classification of lung cancer in small biopsies and cytology [2, 25]. H&E stained slides were firstly used for standard morphological diagnosis. Tumors with SqCC morphological features, such as keratinization, intercellular bridge, and keratin pearl formation were diagnosed as SqCC. For those cases composed of poorly differentiated NSCLC without definite SqCC morphology, immunohistochemistry (IHC) was used to assist the pathological diagnosis. Cases positive for SqCC markers (p40 or CK5/6) with at least moderate to diffuse staining pattern and strong intensity, and negative for ADC markers (TTF-1 and/or mucin) were classified as NSCC favor SqCC. Cases with final diagnosis of SqCC or NSCC favor SqCC determined from small biopsies were further analyzed for EGFR mutation status and those without additional tissue sections for molecular tests were excluded in this study. This retrospective study was approved by the Institutional Review Board of Taipei Veterans General Hospital (2017–05-008CC).

Scoring of immunohistochemistry

The tissue sections were immunostained with commercially available antibodies including thyroid transcription factor-1 (TTF-1) (clone 8G7G3/1, Dako), p40 (clone BC28, Biocare Medical) and CK5/6 (clone D5/16 B4, Dako) on a Leica BOND-MAX system (Leica Microsystems, Newcastle, UK). Tumors completely absent of TTF-1 staining were considered as TTF-1 negative. For p40 or CK5/6 staining, the moderate staining pattern was defined as 10 to 50% of tumor cells showing immunoreactivity, while the diffuse staining pattern was defined as more than 50% of tumor cells with immunoreactivity. Cases with staining intensity similar to internal controls represented by bronchial/bronchiolar basal cell layer were recognized as strong intensity.

EGFR mutation analysis

H&E stained tissue slides were reviewed by pathologists to select the tumor areas and the selected areas were microdissected manually from the corresponding ones in the consecutive tissue sections and, after deparaffinization, were subjected to genomic DNA extraction. Briefly, the microdissected tumor tissue was transferred to an eppendorf tube containing Proteinase K solution (PicoPure™ DNA Extraction Kit, Applied Biosystems™). The tube was then incubated at 56 °C for 16 h, followed by an inactivation step at 95 °C for 10 min. The Proteinase K digested extract was adequate for molecular tests. Since EGFR exon 19 deletions and L858R mutation are the most common types of EGFR mutations, together accounting for approximately 90% of TKI-sensitive mutations, TaqMan EGFR Exon 19 Deletions Assay, L858R Mutation Detection Assay and Reference Assay (Invitrogen Life Technologies Inc., Waltham, MA, USA) were used to examine EGFR mutations according to the manufacturer’s instruction. Real-time PCR was performed using the StepOnePlus™ Real-Time PCR System (Applied Biosystems). The mutation status of a sample was determined by using the parameter described previously [26]. Samples were considered as mutation positive if a specific sigmoid curve was observed with Ct of mutation reaction ≤37 and/or ΔCt value ≤7.

Statistical analysis

The correlation between patients’ clinicopathological features and EGFR mutation status was assessed using chi-square test or independent sample t-test. For multivariate analysis, logistic regression model was used. All analyses were performed using the Statistical Product and Service Solutions program 18.0 for windows (SPSS, Chicago, IL). p value below 0.05 was considered to indicate statistical significance.

Results

Patients’ clinical characteristics

One hundred and forty-eight patients diagnosed as SqCC or NSCC favor SqCC from small biopsies were enrolled in this study. The patients’ clinicopathological characteristics were summarized in Table 1. There were 78 (52.7%) male and 70 (47.3%) female patients ranging from 41 to 93 years (median age, 73 years). Among them, 135 (91.2%) were diagnosed as SqCC based on standard H&E morphological criteria, while 13 (8.8%) were NSCC favor SqCC based on IHC results. Of 128 patients with known smoking status, 39 (30.5%) were never smokers and 89 (69.5%) were current or ever smokers. For methodologies of obtaining biopsy specimens, 72 (56.7%) were through bronchoscopy, 40 (31.5%) computed tomography (CT) guided-biopsy, and 15 (11.8%) sono-guided biopsy. The average of biopsy pieces per sample was 4.4 ranging from 1 to 13 pieces, and the mean size of samples was 6.6 mm in the largest diameter.

EGFR mutation status

As shown in Table 1, EGFR mutations were found in 8.8% (13/148) of all cases with 7 (53.8%) having L858R mutation, 4 (30.8%) exon 19 deletions, and 2 (15.4%) coexistence of L858R and T790 M mutations. Among EGFR mutation-positive cases, 76.9% (10/13) were female, 83.3% (10/12) were never smokers, and 46.2% (6/13) were NSCC favor SqCC. In univariate analysis, EGFR mutations were more frequently observed in female (76.9% versus 23.1%, p = 0.039), never smokers (83.3% versus 16.7%, p < 0.0001), and patients diagnosed as NSCC favor SqCC (46.2% versus 5.1%, p < 0.0001). Neither age, nor biopsy methods, nor the pieces and size of biopsy samples was significantly associated with EGFR mutations. The multivariate analysis showed that EGFR mutations were only significantly associated with never smokers (p = 0.006) and patients with a diagnosis of NSCC favor SqCC (p = 0.001).

Pathological features in EGFR mutation-positive SqCC diagnosed from small biopsies

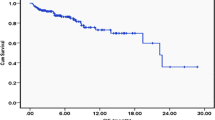

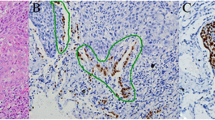

As shown in Table 2, among 13 EGFR mutation-positive cases, 7 were diagnosed as SqCC based on standard H&E morphological criteria with keratinization, intercellular bridge or keratin pearl formation. These cases showed strong and diffuse nuclear staining of p40, and negative staining of TTF-1 in IHC analysis. A representative case was shown in Fig. 1. There were 6 cases initially diagnosed as NSCLC-not otherwise specified (NOS) based on H&E staining, showing poorly-differentiated NSCC without glandular, squamous, or neuroendocrine differentiation. These cases were finally diagnosed as NSCC favor SqCC based on IHC results showing moderate to diffuse staining and moderate or strong intensity of p40 or CK5/6, and negative staining of TTF-1 and mucin. A representative case was illustrated in Fig. 2. Moreover, 4 of 13 EGFR mutation-positive cases had additional follow-up tumor tissues due to further surgical resection or rebiopsy after initial diagnosis. Three of them had their subsequent lobectomy specimens showing ADSC and one showed exclusively SqCC morphology in the follow-up lung biopsy (Table 2).

A representative case showing moderately differentiated SqCC in bronchoscopic biopsy diagnosed as adenosquamous carcinoma after surgical resection. a Bronchoscopic biopsy specimen displaying classical SqCC morphology with keratin pearl formation. b, c Tumor cells in the biopsy specimen positive for p40 and negative for TTF-1 staining. d Subsequent surgical resection demonstrating a diagnosis of ADSC. e, f The squamous carcinoma component immunoreactive with p40 and non-reactive with TTF-1, while the adenocarcinoma component immunoreactive with TTF-1 and non-reactive with p40. g Real-time PCR analysis of the biopsy specimen positive for EGFR exon 19 deletions

A representative case showing poorly differentiated NSCC favor SqCC in bronchoscopic biopsy positive for EGFR L858R mutation. a Poorly differentiated carcinoma with distinct cell border and abundant cytoplasm. b, c Tumor cells with diffuse and strong staining of p40 and negative staining of TTF-1. d Real-time PCR analysis positive for EGFR L858R mutation

Discussion

Recent advances in targeted therapy have dramatically changed the clinical management of lung cancer patients and the molecular testing for driver mutations is now routinely used to predict patients’ treatment response. The current guideline of CAP/IASLC/AMP suggests that testing for EGFR mutations and anaplastic lymphoma kinase (ALK) translocations should be recommended for adenocarcinomas and mixed lung cancers with an adenocarcinomatous component, regardless of histologic grade, and are not recommended in lung cancers that lack any adenocarcinoma component, such as “pure” SqCC, “pure” SCLC, or large cell carcinomas lacking any IHC evidence of adenocarcinoma differentiation [20]. In the era of precision medicine, accurate pathologic classification of NSCLC is mandatory for tailoring patients to specific molecular diagnostic testing. However, most of advanced lung cancers are diagnosed via tumor biopsies, which increases the difficulty in making a correct diagnosis, particularly in tumors without clear differentiation or in mixed-type tumors, such as ADSC.

Our study focuses on investigating the impact of EGFR mutation testing on ADSC in small biopsy diagnostics, especially in Asian patients that have high incidence of EGFR mutations. The misdiagnosis of ADSC remains a problem in up to 20% of small biopsy cases, even using immunohistochemistry [23, 27]. A recent study reported by Zhang et al. showed that 38.8% (26/67) of post-operatively pathologically proven ADSC patients were pre-operatively misdiagnosed as SqCC and 29.8% (20/67) were misdiagnosed as poorly differentiated SqCC via biopsy or cytology specimens [28]. In this study, we found EGFR mutations are detected in 8.8% of small biopsy-diagnosed SqCC or NSCC favor SqCC, and significantly associated with never smokers and a diagnosis of NSCC favor SqCC. It has been reported that the incidence of EGFR mutations in Asian SqCC is less than 3% [29]. The frequency of EGFR mutations in our cases is higher than that reported in SqCC, suggesting that some of these small biopsy cases may not be single-histology SqCC. Indeed, three of 4 (75%) EGFR mutation-positive cases in our study are subsequently diagnosed as ADSC, suggesting that most of EGFR-mutated SqCC diagnosed from small biopsies may result from undersampling of ADSC.

The limitation of this study is that this is a retrospective study and patients who are diagnosed as SqCC in small biopsies would not receive EGFR-TKI treatment according to current guidelines, therefore, no treatment results are available for analysis. Moreover, due to the rarity of ADSC and its unfeasibility in small biopsy diagnosis, data on the efficacy of EGFR-TKI in ADSC patients is limited. Although there were only a limited number of cases published, some studies demonstrated that using EGFR-TKIs is an effective treatment for patients with EGFR-mutated ADSC (Table 3) [17, 28, 30]. Song et al. showed that the progression-free survival of ADSC patients with EGFR-TKIs treatment was 4.3 months which is comparable to 4.2 months of ADC. They also revealed higher efficacy of EGFR-TKIs in ADSC patients with EGFR mutations compared to those without EGFR mutations. In Fan et al. and Zhang et al. studies, EGFR-TKIs were only applied to EGFR activating mutation-positive patients, and the average of disease control rate and overall survival were 75.4% and 41 months. Zhang et al. also showed that ADSC patients harboring EGFR-sensitizing mutations who were treated with EGFR-TKIs had a significantly better prognosis than those receiving chemotherapy or chemoradiotherapy alone [28]. However, these studies only included patients with clinical stage I to IIIA, and a prospective study toward efficacy of EGFR-TKIs in advanced stage ADSC patients needs to be further conducted in the future.

Our multivariate analyses showed that never-smokers and NSCC favor SqCC, but not female gender, are independently associated with EGFR mutations. Lung cancer in never smokers has significant gender and geographic variations, occurring more frequently in female and in Asia. One possible explanation is that the majority of female NSCLC patients in Asian populations have no smoking history. Studies showed that the proportion of never smokers in female lung cancer cases are 83% in South Asia, while only 15% in the United States [31]. Moreover, lung cancer in Asian never smokers are often diagnosed as ADC that can be classified into different molecular subtypes based on oncogenic driver mutations. On the contrary, SqCC is more significantly associated with smokers than other subtypes of NSCLC [32]. From a molecular point of view, several studies showed that EGFR mutations are more prevalent in tumors of never smokers, while TP53 and KRAS mutations are more frequently found in smokers [31, 33,34,35]. Taken together, in our study cohort, the clinicopathological characteristics of EGFR mutation-positive cases are similar to those of ADC, implying that some of these cases might be EGFR-mutated ADSC. Furthermore, our findings that EGFR mutations significantly associate with a diagnosis of NSCC favor SqCC, which is defined as poorly differentiated NSCLC without definite SqCC morphology features, also suggest these cases may possibly be ADSC.

Conclusions

EGFR-TKI is a therapeutic option of EGFR-mutated ADSC which is often misdiagnosed as SqCC in small lung biopsies, resulting in absence of EGFR mutation testing. Our findings demonstrated the importance of EGFR mutation testing in small biopsy-diagnosed lung SqCC, especially in never smokers and patients whose diagnoses need to be assisted by immunohistochemistry.

Availability of data and materials

The datasets supporting the conclusions of this article are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

Abbreviations

- ADC:

-

Adenocarcinoma

- ADSC:

-

Adenosquamous carcinoma

- ALK:

-

Anaplastic lymphoma kinase

- CAP/IASLC/AMP:

-

The College of American Pathologists (CAP), the International Association for the Study of Lung Cancer (IASLC), and the Association for Molecular Pathology (AMP)

- EGFR:

-

Epidermal growth factor receptor

- EGFR-TKIs:

-

Epidermal growth factor receptor tyrosine kinase inhibitors

- IHC:

-

Immunohistochemistry

- LCC:

-

Large cell carcinoma

- NSCC:

-

Non-small cell carcinoma

- NSCLC:

-

Non-small cell lung cancer

- SCLC:

-

Small cell lung cancer

- SqCC:

-

Squamous cell carcinoma

- TTF-1:

-

Thyroid transcription factor-1

- WHO:

-

World Health Organization

References

Siegel R, Ma J, Zou Z, Jemal A. Cancer statistics, 2014. CA Cancer J Clin. 2014;64:9–29.

Travis WD, Brambilla E, Nicholson AG, Yatabe Y, Austin JHM, Beasley MB, Chirieac LR, Dacic S, Duhig E, Flieder DB, Geisinger K, Hirsch FR, Ishikawa Y, Kerr KM, Noguchi M, Pelosi G, Powell CA, Tsao MS, Wistuba I, Panel WHO. The 2015 World Health Organization classification of lung tumors: impact of genetic, clinical and radiologic advances since the 2004 classification. J Thorac Oncol. 2015;10:1243–60.

Cooke DT, Nguyen DV, Yang Y, Chen SL, Yu C, Calhoun RF. Survival comparison of adenosquamous, squamous cell, and adenocarcinoma of the lung after lobectomy. Ann Thorac Surg. 2010;90:943–8.

Filosso PL, Ruffini E, Asioli S, Giobbe R, Macri L, Bruna MC, Sandri A, Oliaro A. Adenosquamous lung carcinomas: a histologic subtype with poor prognosis. Lung Cancer. 2011;74:25–9.

Wang J, Wang Y, Tong M, Pan H, Li D. Research progress of the clinicopathologic features of lung adenosquamous carcinoma. OncoTargets Ther. 2018;11:7011–7.

Dacic S. Molecular genetic testing for lung adenocarcinomas: a practical approach to clinically relevant mutations and translocations. J Clin Pathol. 2013;66:870–4.

Ulivi P, Zoli W, Capelli L, Chiadini E, Calistri D, Amadori D. Target therapy in NSCLC patients: relevant clinical agents and tumour molecular characterisation. Mol Clin Oncol. 2013;1:575–81.

Rosell R, Moran T, Queralt C, Porta R, Cardenal F, Camps C, Majem M, Lopez-Vivanco G, Isla D, Provencio M, Insa A, Massuti B, Gonzalez-Larriba JL, Paz-Ares L, Bover I, Garcia-Campelo R, Moreno MA, Catot S, Rolfo C, Reguart N, Palmero R, Sanchez JM, Bastus R, Mayo C, Bertran-Alamillo J, Molina MA, Sanchez JJ, Taron M, Spanish Lung Cancer G. Screening for epidermal growth factor receptor mutations in lung cancer. N Engl J Med. 2009;361:958–67.

Shi Y, Au JS, Thongprasert S, Srinivasan S, Tsai CM, Khoa MT, Heeroma K, Itoh Y, Cornelio G, Yang PC. A prospective, molecular epidemiology study of EGFR mutations in Asian patients with advanced non-small-cell lung cancer of adenocarcinoma histology (PIONEER). J Thorac Oncol. 2014;9:154–62.

Goto K, Ichinose Y, Ohe Y, Yamamoto N, Negoro S, Nishio K, Itoh Y, Jiang H, Duffield E, McCormack R, Saijo N, Mok T, Fukuoka M. Epidermal growth factor receptor mutation status in circulating free DNA in serum: from IPASS, a phase III study of gefitinib or carboplatin/paclitaxel in non-small cell lung cancer. J Thorac Oncol. 2012;7:115–21.

Mitsudomi T, Morita S, Yatabe Y, Negoro S, Okamoto I, Tsurutani J, Seto T, Satouchi M, Tada H, Hirashima T, Asami K, Katakami N, Takada M, Yoshioka H, Shibata K, Kudoh S, Shimizu E, Saito H, Toyooka S, Nakagawa K, Fukuoka M, West Japan Oncology G. Gefitinib versus cisplatin plus docetaxel in patients with non-small-cell lung cancer harbouring mutations of the epidermal growth factor receptor (WJTOG3405): an open label, randomised phase 3 trial. Lancet Oncol. 2010;11:121–8.

Mok TS, Wu YL, Thongprasert S, Yang CH, Chu DT, Saijo N, Sunpaweravong P, Han B, Margono B, Ichinose Y, Nishiwaki Y, Ohe Y, Yang JJ, Chewaskulyong B, Jiang H, Duffield EL, Watkins CL, Armour AA, Fukuoka M. Gefitinib or carboplatin-paclitaxel in pulmonary adenocarcinoma. N Engl J Med. 2009;361:947–57.

Sharma SV, Bell DW, Settleman J, Haber DA. Epidermal growth factor receptor mutations in lung cancer. Nat Rev Cancer. 2007;7:169–81.

Jia XL, Chen G. EGFR and KRAS mutations in Chinese patients with adenosquamous carcinoma of the lung. Lung Cancer. 2011;74:396–400.

Kang SM, Kang HJ, Shin JH, Kim H, Shin DH, Kim SK, Kim JH, Chung KY, Kim SK, Chang J. Identical epidermal growth factor receptor mutations in adenocarcinomatous and squamous cell carcinomatous components of adenosquamous carcinoma of the lung. Cancer. 2007;109:581–7.

Sasaki H, Endo K, Okuda K, Kawano O, Kitahara N, Tanaka H, Matsumura A, Iuchi K, Takada M, Kawahara M, Kawaguchi T, Yukiue H, Yokoyama T, Yano M, Fujii Y. Epidermal growth factor receptor gene amplification and gefitinib sensitivity in patients with recurrent lung cancer. J Cancer Res Clin Oncol. 2008;134:569–77.

Song Z, Lin B, Shao L, Zhang Y. Therapeutic efficacy of gefitinib and erlotinib in patients with advanced lung adenosquamous carcinoma. J Chin Med Assoc. 2013;76:481–5.

Toyooka S, Yatabe Y, Tokumo M, Ichimura K, Asano H, Tomii K, Aoe M, Yanai H, Date H, Mitsudomi T, Shimizu N. Mutations of epidermal growth factor receptor and K-ras genes in adenosquamous carcinoma of the lung. Int J Cancer. 2006;118:1588–90.

Chiu CH, Chou TY, Chiang CL, Tsai CM. Should EGFR mutations be tested in advanced lung squamous cell carcinomas to guide frontline treatment? Cancer Chemother Pharmacol. 2014;74:661–5.

Kalemkerian GP, Narula N, Kennedy EB, Biermann WA, Donington J, Leighl NB, Lew M, Pantelas J, Ramalingam SS, Reck M, Saqi A, Simoff M, Singh N, Sundaram B. Molecular testing guideline for the selection of patients with lung cancer for treatment with targeted tyrosine kinase inhibitors: American Society of Clinical Oncology endorsement of the College of American Pathologists/International Association for the Study of Lung Cancer/Association for Molecular Pathology Clinical Practice Guideline update. J Clin Oncol Off J Am Soc Clin Oncol. 2018;36:911–9.

Travis WD, Brambilla E, Noguchi M, Nicholson AG, Geisinger KR, Yatabe Y, Beer DG, Powell CA, Riely GJ, Van Schil PE, Garg K, Austin JH, Asamura H, Rusch VW, Hirsch FR, Scagliotti G, Mitsudomi T, Huber RM, Ishikawa Y, Jett J, Sanchez-Cespedes M, Sculier JP, Takahashi T, Tsuboi M, Vansteenkiste J, Wistuba I, Yang PC, Aberle D, Brambilla C, Flieder D, Franklin W, Gazdar A, Gould M, Hasleton P, Henderson D, Johnson B, Johnson D, Kerr K, Kuriyama K, Lee JS, Miller VA, Petersen I, Roggli V, Rosell R, Saijo N, Thunnissen E, Tsao M, Yankelewitz D. International association for the study of lung cancer/american thoracic society/european respiratory society international multidisciplinary classification of lung adenocarcinoma. J Thorac Oncol. 2011;6:244–85.

Travis WD, Rekhtman N. Pathological diagnosis and classification of lung cancer in small biopsies and cytology: strategic management of tissue for molecular testing. Semin Respir Crit Care Med. 2011;32:22–31.

Rekhtman N, Paik PK, Arcila ME, Tafe LJ, Oxnard GR, Moreira AL, Travis WD, Zakowski MF, Kris MG, Ladanyi M. Clarifying the spectrum of driver oncogene mutations in biomarker-verified squamous carcinoma of lung: lack of EGFR/KRAS and presence of PIK3CA/AKT1 mutations. Clin Cancer Res. 2012;18:1167–76.

Rajeev Saini UB, Jain A, Agrawal C. EGFR mutation -- a commonly neglected mutation in squamous cell lung carcinoma. J Cancer Metastasis Treat. 2016;2:2.

Yatabe Y, Dacic S, Borczuk AC, Warth A, Russell PA, Lantuejoul S, Beasley MB, Thunnissen E, Pelosi G, Rekhtman N, Bubendorf L, Mino-Kenudson M, Yoshida A, Geisinger KR, Noguchi M, Chirieac LR, Bolting J, Chung JH, Chou TY, Chen G, Poleri C, Lopez-Rios F, Papotti M, Sholl LM, Roden AC, Travis WD, Hirsch FR, Kerr KM, Tsao MS, Nicholson AG, Wistuba I, Moreira AL. Best practices recommendations for diagnostic immunohistochemistry in lung cancer. J Thorac Oncol. 2019;14:377–407.

Kao HL, Yeh YC, Lin CH, Hsu WF, Hsieh WY, Ho HL, Chou TY. Diagnostic algorithm for detection of targetable driver mutations in lung adenocarcinomas: comprehensive analyses of 205 cases with immunohistochemistry, real-time PCR and fluorescence in situ hybridization methods. Lung Cancer. 2016;101:40–7.

Borczuk AC. Uncommon types of lung carcinoma with mixed histology: Sarcomatoid carcinoma, Adenosquamous carcinoma, and Mucoepidermoid carcinoma. Arch Pathol Lab Med. 2018;142:914–21.

Zhang C, Yang H, Lang B, Yu X, Xiao P, Zhang D, Fan L, Zhang X. Surgical significance and efficacy of epidermal growth factor receptor tyrosine kinase inhibitors in patients with primary lung adenosquamous carcinoma. Cancer Manag Res. 2018;10:2401–7.

Fang W, Zhang J, Liang W, Huang Y, Yan Y, Wu X, Hu Z, Ma Y, Zhao H, Zhao Y, Yang Y, Xue C, Zhang J, Zhang L. Efficacy of epidermal growth factor receptor-tyrosine kinase inhibitors for Chinese patients with squamous cell carcinoma of lung harboring EGFR mutation. J Thorac Dis. 2013;5:585–92.

Fan L, Yang H, Yao F, Zhao Y, Gu H, Han K, Zhao H. Clinical outcomes of epidermal growth factor receptor tyrosine kinase inhibitors in recurrent adenosquamous carcinoma of the lung after resection. OncoTargets Ther. 2017;10:239–45.

Sun S, Schiller JH, Gazdar AF. Lung cancer in never smokers--a different disease. Nat Rev Cancer. 2007;7:778–90.

Khuder SA. Effect of cigarette smoking on major histological types of lung cancer: a meta-analysis. Lung Cancer. 2001;31:139–48.

Shigematsu H, Lin L, Takahashi T, Nomura M, Suzuki M, Wistuba II, Fong KM, Lee H, Toyooka S, Shimizu N, Fujisawa T, Feng Z, Roth JA, Herz J, Minna JD, Gazdar AF. Clinical and biological features associated with epidermal growth factor receptor gene mutations in lung cancers. J Natl Cancer Inst. 2005;97:339–46.

Tam IY, Chung LP, Suen WS, Wang E, Wong MC, Ho KK, Lam WK, Chiu SW, Girard L, Minna JD, Gazdar AF, Wong MP. Distinct epidermal growth factor receptor and KRAS mutation patterns in non-small cell lung cancer patients with different tobacco exposure and clinicopathologic features. Clin Cancer Res. 2006;12:1647–53.

Le Calvez F, Mukeria A, Hunt JD, Kelm O, Hung RJ, Taniere P, Brennan P, Boffetta P, Zaridze DG, Hainaut P. TP53 and KRAS mutation load and types in lung cancers in relation to tobacco smoke: distinct patterns in never, former, and current smokers. Cancer Res. 2005;65:5076–83.

Acknowledgements

We would like to thank Wen-Yu Hsieh and Chun-An Kuo for technical assistance.

Funding

This study was supported by grants V104A-018 from Taipei Veterans General Hospital and MOHW107-TDU-B-211-114019 from the Ministry of Health and Welfare.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

HHL and KHL initiated and designed this study. KHL and YYC collected patients and clinicopathological data and were responsible for pathological diagnosis. HHL was responsible for EGFR mutation analysis. The interpretation of results and drafting of the manuscript were performed by HHL and KHL. CTY supervised the research and revised the manuscript. HHL and KHL contributed equally to this work and should be considered as “co-first authors”. All authors have read and approved the submitted version of manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate

This study was approved by the Institutional Review Board of Taipei Veterans General Hospital (2017–05-008CC). Formal patient consent was waived because of the retrospective study design.

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/), which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made. The Creative Commons Public Domain Dedication waiver (http://creativecommons.org/publicdomain/zero/1.0/) applies to the data made available in this article, unless otherwise stated.

About this article

Cite this article

Ho, HL., Kao, HL., Yeh, YC. et al. The importance of EGFR mutation testing in squamous cell carcinoma or non-small cell carcinoma favor squamous cell carcinoma diagnosed from small lung biopsies. Diagn Pathol 14, 59 (2019). https://doi.org/10.1186/s13000-019-0840-2

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/s13000-019-0840-2