Abstract

There is considerable interest in exploring effects of coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) pandemic on mental health. Suicide is one of the leading causes of mortality worldwide and changes in daily life brought by the pandemic may be additional risk factors in people with pre-existing mental disorders. This rapid PRISMA-ScR (Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses extension for Scoping Reviews) scoping review aims to identify and analyze current evidence about the relation between COVID-19 pandemic outbreak, along with COVID-19 disease and severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2 (SARS-CoV2) infection, and suicide in individuals with previously diagnosed mental disorders. First, we conducted a comprehensive review of the literature, then proceeded to discuss findings in a narrative way. Tables were constructed and articles sorted according to the studies’ methodologies. 53 papers were eventually identified as eligible, among which 33 are cross-sectional studies, 9 are longitudinal studies, and 11 studies using other methodologies. Despite suffering from a mental disorder is a risk factor for suicidal behavior per se, the advent of COVID-19 pandemic may exacerbate this relation. Nevertheless, data addressing a clear correlation between suicidal behavior and the pandemic outbreak are still controversial. Longitudinal analysis using validated suicide scales and multicenter studies could provide deeper insight and knowledge about this topic.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

The advent of the pandemic has drastically impacted our daily lives. At the time of writing, more than 505,560,928 million people worldwide have been infected with severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2 (SARS-CoV2), causing 6,226,457 deaths [1]. Suicide is a complex multifactorial phenomenon and a leading cause of death worldwide. Most suicides are related to psychiatric diseases, and individuals with mental disorders are at increased risk [2]. Based on the data on suicide rates relating to the previous epidemics, a rise in suicide was observed between 1918 and 1919 during the influenza epidemic in the United States [3]. These data are also consistent with increased levels of suicide among older adults during the 2003 SARS epidemic in Hong Kong [4]. During the current pandemic, extraordinary measures for treatment and prevention of infection have been put in place by governments, such as quarantines, lockdowns, and social distancing. An increase in the incidence of mental disorders such as acute stress disorder, anxiety, irritability, PTSD, elevated psychological distress, depressive symptoms, and insomnia may have been caused by the previously stated measurement [5]. All these disturbances are related to an increase in suicide risk [6]. As already demonstrated by longitudinal studies, also economic crises and unemployment have been linked to increased suicide rates [7]. Therefore, the economic downturn resulting from the advent of the coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) pandemic may also be considered an additional risk factor for suicidal behavior [8]. Moreover, fear of infection, already shown as a prominent risk factor [9], social isolation, and grief may further contribute to a robust increase in suicidal behavior. SARS-CoV2 infection per se has proven to be a potential risk factor for suicidal behavior [10] and may eventually be included within COVID-19 sequelae. Furthermore, during the first phases of the pandemic outbreak, we witnessed a dramatic increase in difficulties in referring to psychiatric departments [11], along with a drastic reduction in outpatient medical care accessibility. As a result, patients with pre-existing mental disorders may have experienced an exacerbation of symptoms such as feelings of loneliness, anxiety, depression, insomnia, and hopelessness, which might eventually lead to a decrease in treatment compliance, increasing the risk of suicidal behavior [12]. Although data on previous epidemics demonstrated a correlation with increased suicide rates, the influence of the COVID-19 pandemic on suicide trends is still debated and controversial [13]. A recent meta-analysis carried out by Dubè et al. [14] highlighted how the COVID-19 pandemic had increased suicide risk in the general population; however, data regarding suicide behavior during the COVID-19 pandemic in subjects with pre-existing mental disorders are still scarce, and strong data are lacking. In this scenario, the present study aims to highlight current evidence on suicide and the COVID-19 pandemic, including studies also addressing this relation with SARS-CoV2 infection and the proper disease (to which we will refer as COVID-19 disease), in subjects with psychiatric disorders and to fill the gaps in the literature regarding this topic.

Methods

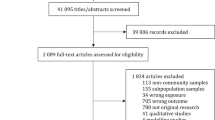

A comprehensive review of the literature was carried out on Pubmed up to April 2, 2022. Considering the extensive aim of the study, we used Medical Subject Headings (MeSH) descriptors (“COVID-19”[Mesh]) AND ”Suicide”[Mesh]). To maximize the sensitivity of our study, we did not provide additional terms besides “Suicide” and “COVID-19”. Subsequently, the studies included were discussed with a narrative overview. Aiming to cover a broad literature overview and considering that strong evidence regarding suicide rates in subjects with a pre-existing mental disorder during the pandemic is still lacking, a rapid PRISMA-ScR (Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses extension for Scoping Reviews) scoping review, following the statement guidelines for scoping reviews [15], was identified as the best method to carry out the present study [16]. Only articles published between March 2020, the declaration of the pandemic [17], and April 2022 were selected. Papers included examined suicidal behavior during the pandemic, the correlation between suicide rates and the pandemic itself in cross-sectional analyses, or changes in suicidal behavior in a longitudinal perspective; finally, other studies providing useful information on clinically observable suicidal behavior during the pandemic were included. In the present review we included not only studies that addressed suicidality in relation to COVID-19 pandemic, but also in relation to SARS-CoV2 infection and in COVID-19 disease. Only studies that included subjects with previous mental illness and assessed suicide behavior and risk were taken into consideration. Specifically, whether the sample included general population, the study only considered available data on suicide assessment in individuals with previously diagnosed mental illness. We excluded studies on topics other than suicide and COVID-19 pandemic, infection and disease, and in languages other than English. Being the present study a scoping review, the quality of studies is not necessarily addressed [18]; therefore, meta-analysis, reviews, and systematic reviews were excluded. Papers found to be purely narrative papers, editorials, books chapter, letters to editors, comments, and case reports with small samples (< 10 subjects) were excluded since they would not provide significant insight into the researched topic. Two independent reviewers screened citations for inclusion. Data extraction was conducted by one reviewer and verified by a second reviewer. Tables were then constructed, and articles were sorted out by authors, title, location of the study, sample size, nature of the sample, purpose/aim of the study, suicide assessments measures, type of publishing, time points compared/ analyzed in the study, and principal findings. In the narrative overview, studies were categorized by methodological approach (cross-sectional vs. longitudinal) and type of sample (patients vs. general population). Results were then discussed.

Search results

The initial Pubmed search yielded a total of 502 results. Three additional titles were identified through other sources (website searching, citation tracking, and reference chaining). 10 records were excluded as not full text. The remaining 495 full-text records titles and abstracts were screened, and 135 were excluded as the article's primary focus was not the correlation between suicide and COVID-19, being therefore irrelevant to the present study's aim. Among the remaining 360 papers, 84 were excluded since they did not meet the inclusion criteria. Specifically, 79 articles were excluded as 16 were reviews, 16 case reports, 3 systematic reviews, 18 comments, 23 editorials, 2 meta-analyses, and 1 was retracted. 5 articles were excluded as being published 1 in French, 1 in Hungarian, 1 in German, 1 in Turkish, 1 in Italian. Of the resulting 276 eligible records, 223 were excluded as they did not provide adequate information about the relation between COVID-19 and suicide behavior, or the sample considered did not include subjects with a pre-existing mental condition. 53 papers were finally identified as of particular interest. The selected articles are presented in Tables 1, 2, 3, 4 and 5 and discussed in the narrative overview.

For specifics about the study design, consult Fig. 1.

Narrative overview

Among the 53 articles identified as eligible for directly assessing modifications of suicidal behavior during COVID-19 pandemic in patients with pre-existing mental disorders, 33 are cross-sectional studies, 9 are longitudinal studies, and 11 studies employed other methods.

Four longitudinal studies assessed in this review included patient samples, and the remaining 5 studied this correlation in general population samples.

Focusing on longitudinal investigations in patient samples, the 4 articles were carried out in different countries, namely 1 in Iran, 1 in Spain, 1 in the USA, and 1 in Denmark [19,20,21,22]. Two studies assessed suicide behavior in patients previously diagnosed with obsessive–compulsive disorder (OCD) [19, 20], one in a nationally representative cohort of US veterans with pre-existing mental health conditions [21] and one in individuals admitted to hospitals and Emergency Medical Services presenting psychopathological symptomatology [22]. In the study conducted in the USA by Na et al., suicidal behavior was assessed by means of the Patient Health Questionnaire-9 (PHQ-9); the two studies, carried out in Spain by Alonso et al. and in Iran by Khosravani et al., assessing patients with OCD employed Hamilton Depression Rating Scale (HDRS) item on suicide and Beck Scale for Suicidal Ideation (BSSI), respectively. The Danish study collected data regarding diagnoses from electronic health records (EHRs)—including codes for suicide and self‐harm—defined and coded according to the ICD‐10 system by the responsible clinicians. 3 out of 4 studies identified mental illness as a risk factor for suicide and addressed a relationship between the outbreak of the pandemic and an increase in suicidal behavior. Specifically, the study conducted by Na et al. relates ongoing SARS-CoV2 infection with an increased risk of suicidal behavior in subjects already suffering from a mental disorder. The study conducted in Denmark revealed how most patients exhibiting suicidal behavior during the pandemic presented a pre-existing mental disorder. However, the hospital‐registered rate of suicidal events during the pandemic significantly did not change when compared to the pre‐pandemic period. For specifics about these studies, see Table 1.

Among longitudinal studies using a general population sample, 1 was carried out in Greece, 2 in the USA, 1 in Australia, and 1 was an international study spanning over 40 countries and including up to 55,589 participants [23,24,25,26,27]. Two studies assessed suicidal behavior among US veterans [24, 25], and 2 studies analyzed national representative samples from Australia (by Batterham et al.) and Greece (by Fountoulakis et al.), respectively, evaluating suicide risk by means of the suicidal item of PHQ-9 and Risk Assessment Suicidality Scale (RASS); the two studies among veterans used Suicidal Behaviors Questionnaire-Revised (SBQ-R) and PHQ-9. The international study used the RASS for suicide assessment. Most of the studies demonstrated a correlation between the presence of suicidal behavior during the pandemic with previous mental health conditions. Conversely, the study carried out by Batterham et al. in Australia evidenced that a previously diagnosed psychiatric disorder, despite being a risk factor for suicidal behavior, is not significantly associated with incident suicidal ideation during the pandemic. The study conducted in Greece highlighted how a previous history of depression, self-harm, and suicidal attempts represent risk factors for relapsing depression and, eventually, suicidality during the pandemic. The study carried out by Nichter et al. underlined how a history of suicide attempt, lifetime post-traumatic stress disorder and/or depression, and past-year alcohol use disorder severity can be classified as risk factors, among COVID-19-related variables, for new-onset suicidal ideation. The international study conducted among 40 countries highlighted how suffering from a previous mental condition acted as a risk factor and suicidal behavior resulted increased in those people during pandemic. For specifics about these studies, see Table 2.

When screening cross-sectional studies, we identified 12 conducted on patient’s sample and 21 on general population samples.

Among cross-sectional studies analyzing the overstated correlation in patients with a pre-existing psychiatric disorder, one was carried out in China, 3 in Italy, 2 in South Korea, 2 in the USA, 1 in Germany, 1 in Turkey, 1 in Denmark, and 1 in Saudi Arabia [8, 28,29,30,31,32,33,34,35,36,37,38]. Most were service utilization studies, gaining clinical information from hospital admission records or clinical records. The study conducted in China by Liu et al. assessed suicide risk using 3 standardized ("yes" or "no") questions in older clinically stable patents with psychiatric disorders [28]. Two Italian studies were conducted by the same research group (from Sant'Andrea Hospital in Rome), one, by Montalbani et al., used Columbia Suicide Severity Rating Scale (C-SSRS) for suicide assessment, while the other, carried out by Berardelli et al. evaluated suicide attempt (SA) at the time of hospital admission, and suicide ideation (SI) and non-suicidal self-injury (NSSI) by means of the C-SSRS as well [29, 30]; in the study conducted by Almaghrebi et al. in Saudi Arabia suicide risk factors were assessed by means of the Modified SAD PERSONS Scale (MSPS) [8]. The two Korean studies recorded data on patients and assessed suicide lethality with the Risk-Rescue Rating in Suicide assessment (RRRS) and the severity of the suicide attempt on the South Korean Triage and Acuity Scale (KTAS) [31, 32]. The Turkish study focused on relapse rates defining criteria, including new-onset suicide behavior or ideation, to assess suicide risk during the first trimester since the declaration of the pandemic [33]. In the study conducted in Germany, Seifert et al. performed Psychopathological Assessment (PPA) according to the "Arbeitsgemeinschaft für Methodik und Dokumentation in der Psychiatrie" (AMDP)-System on patients presenting to the psychiatric emergency department [34]. Grossman et al., in Massachusetts (USA), obtained data from notes in clinical records regarding suicidality in patients presenting in the emergency department [35]. A study conducted in Kaiser Permanente hospital in Northern California by Ridout et al. assessed population-level incidence rate ratios (IRRs) and percent relative effects for suicide-related emergency department encounters [36]. Jefsen et al., in the Danish study, categorized clinical notes according to diagnosis and identified five distinct categories according to different clinical presentations of suicidal behavior: 1—thoughts of self‐harm, 2—completed self‐harm, 3—passive wish to die of COVID-19, 4—suicidal thoughts, 5—suicide attempts [37]. Slightly more than half of the considered studies evidenced an increase in suicidal behavior, hospital consults, and admissions among patients during the pandemic, underlying the role of pre-existing mental conditions as a risk factor for suicidal behavior. Interestingly, in the study conducted by Liu et al., among the patients exhibiting suicidal behavior, Major Depressive Disorder (MDD) was found to be the most common psychiatric pre-existing diagnosis [28]. Conversely, in the study conducted by Menculini et al. in Perugia (Italy), more than one-third of the considered sample (patients presenting to the emergency room requiring psychiatric consultation) did not report any previous psychiatric history. Authors suggest that a percentage of cases were to be considered as new-onset suicidality, contrasting previously reported findings in which suicide and suicidal behavior were mostly related to pre-existing severe psychiatric disorders [38]. The study conducted by Lee et al. showed how the history of previous suicide attempts and previous psychiatric history were not significant independent risk factors for low-rescue suicide attempts when compared to COVID-19 as a risk factor itself [32]. The study conducted in Germany showed that the rate of patients self-reporting suicidal ideation and intent remained stable between 2019 and 2020. Suicidal ideation was stated significantly more often by patients with substance use disorders in 2020 than in 2019 [34]. Grossman et al. highlighted how accesses to psychiatric care in the COVID-19 post-period groups (case and comparator) were less likely to ascribe suicidality to psychiatric symptoms compared to visits in the comparator post-period group [35]. Finally, the Turkish study underlined how the relapse rate of the sample in 2019 did not differ from the first trimester of COVID-19 [33]. For specifics about these studies, see Table 3.

Among cross-sectional studies conducted on general population samples, 4 were carried out in Spain, 1 in Japan, 1 in Argentina, 1 in Latvia, 1 in Greece, 1 in France, 1 in New Zealand, 1 in Canada, 1 in Belgium, 3 in India, 1 in China, 1 in Honk Kong, 1 in the USA, 1 among Australia and USA, 1 in the UK, 1 in the Czech Republic [39,40,41,42,43,44,45,46,47,48,49,50]. Many of these studies assessed suicide behavior among a nationally representative sample; three of those focused on suicide among hospital workers [39,40,41] two studies analyzed COVID-19-related suicide reported by media, respectively [42, 43] and one assessed suicidal thought through the use of the 22-item Impact of Events Scale-Revised (IES-R) among 69.054 students in France [44], while the study carried out by Behera et al. analyzed autopsies of deaths attributable to suicide [45]. The studies conducted in Spain approached this correlation by employing different scales to assess suicide rates [39, 46,47,48]. Two studies used selected items from a modified version of the C-SSRS [39, 46], while two other Spanish studies, both conducted by Sàiz et al., investigated suicide behavior by means of the Paykel Suicide Scale (PSS) and by questioning participants on whether they experienced "passive suicidal ideation during the past seven days", requiring only yes/, no answers [47, 48]. The study conducted in Belgium used a modified version of selected items from the C-SSRS as well [49], while the Argentinian group employed the Inventory of Suicide Orientation (ISO-30) [50]. Finally, in Latvia, the authors assessed suicidal behavior with RASS [51].

Several different studies explored suicidal ideation by means of the suicidal item of the PHQ-9 [40, 42, 43, 52,53,54,55,56,57,58,59]. Some studies also evaluated suicide behavior without recurring to a validated questionnaire: Kasal et al. assessed the past month's suicide risk using a separate MINI module consisting of 6 questions [55]; in Japan, suicidal ideation was measured through a one-item question with different answer options [56]; in the New Zealand study, participants were interrogated on suicidal ideation, suicide plans, and suicide attempts during the lockdown and the preceding 12 months [57]. Daly et al. too assessed suicidality during the COVID-19 pandemic by directly questioning the participants whether they had ever experienced suicidal thoughts and feelings or past episodes of NSSI [58]. In a study conducted by Harvard University (Boston, Massachusetts, USA) and Monash University (Melbourne, Australia), respondents were required to report whether they had seriously considered suicide in the 30 days preceding the survey [59]. Two Indian studies searched scientific literature, government websites, an online newspaper, and google news to obtain information about suicides during the pandemic [42, 43]. Almost all the studies evidenced an increase in suicidal behavior, mostly related to a pre-existing mental health condition. In the study carried out by Behera et al., the authors suggest that the recurrence of psychiatric symptoms in individuals already diagnosed with mental conditions, such as depression, was associable with an increase in the risk of suicidality among Indian celebrities during the pandemic [45]. Also, Kasal et al. associated Major Depressive Disorder with a higher probability of suicide risk in three different datasets [55]. Al-Humadi et al. study concluded that suicidal ideation was almost entirely associated with a history of depression/anxiety during the COVID-19 pandemic [40]. Moreover, Vrublevska et al. observed an increase in suicidal thoughts of about 13.30% in participants with a history of clinically diagnosed depression and 27.05% in those with a history of suicide attempts during a state of emergency [51]. Conversely, Panigrahi et al. observed that the majority of those deceased by suicide (89.4%, 135) had no comorbid physical/mental illness or substance use [43]. For specifics about these studies, see Table 4.

Finally, we included 11 studies with different methodologies examining the relationship between the COVID-19 pandemic advent and suicide in subjects with pre-existing mental health conditions. Among the selected articles, three of them are case–control studies, respectively, conducted in France, China, and Hong Kong [36, 60, 61]; six are mixed-method studies, one carried out in Austria, two in Australia, one in Ireland, and two in the United States [59, 62,63,64,65,66]; finally, two interrupted time series analysis, from the USA and Sri Lanka, were included [67, 68]. Hedley et al. conducted one of the two studies from Australia and analyzed the impact of the COVID-19 pandemic on a sample of adults diagnosed with Autism Spectrum Disorders by means of a mixed‐method survey design [63]. Veldhuis et al., 2021, conducted a longitudinal survey in 2021 in the USA within a cross-sectional baseline assessment to obtain a better understanding of the long-term effects of the pandemic on mental health [59]. The second study conducted in Australia's Victoria region by Czeisler et al. utilized mixed methods as well, a cross-sectional survey and a longitudinal follow-up [64]. In Ireland, Hyland et al. carried out a cross-sectional analysis in May 2020 on a nationally representative sample of Irish adults (including 1,032 subjects), followed by a longitudinal reassessment carried out in August 2020 [65]. Aiming to estimate the association between the COVID-19 pandemic and Emergency Department (ED) psychiatric presentations (that included suicidal ideation), McDowell et al., from Massachusetts General Hospital in Boston, analyzed the time frame between 2018 and 2020 by employing an interrupted time series analysis [66]. In Hong Kong, Louie et al. carried out a study between March and April 2020, where 33 old adults diagnosed with Major Depressive Disorder (single or recurrent episode, as defined by DSM-5 criteria) were recruited from psychiatric clinics or inpatient wards and eventually compared with 31 healthy older adults with no history of depression [61]. In Sri Lanka, Knipe et al. carried out an interrupted time-series analysis in order to determine the effect of the pandemic on hospital presentations, with a focus on self-poisoning [68]. Carlin et al. carried out a retrospective analysis in the Trauma Centre of the Medical University of Vienna to analyze whether the COVID-19 pandemic affected the rates of hospital admission of patients who attempted suicide by intentionally causing trauma [62]. A retrospective case–control study was also conducted in China, where Hao et al. assessed the immediate stress and psychological impact of the initial phases of the COVID-19 pandemic in 2019 and compared the results between healthy controls and individuals affected by psychiatric illnesses [60]. A case–control study conducted in France assessed, through a cross-sectional survey, both the presence of psychological symptoms and living conditions in two distinct groups, healthy controls (HC) and patients with a recent (within the last 2 years) major depressive episode (PP); results were eventually compared and predictors of significant psychological distress in the PP group were identified [36]. Hamm et al. evaluated through a multicity, mixed-methods (both quantitative and qualitative) study the effect of the COVID-19 pandemic on 73 Community-living older adults with a pre-existing history of Major Depressive Disorder (MDD), aiming to explore this relationship in an older population with a previously diagnosed psychiatric condition [69]. In the study carried out by Veldhuis et al., suicide risk was assessed by means of the Suicidal Ideation Attributes Scale (SIDAS) administered to 1567 subjects from the USA to obtain measures of suicidal thoughts and behaviors and provide an assessment of overall risk [59]. In the study carried out in Hong Kong, suicidal ideation was assessed using Geriatric Suicide Ideation Scale (GSIS) in a sample of adults (healthy controls vs. patients with late-life depression diagnosis) [61]. Two separate studies by Hamm et al. and by Olié et al. assessed suicidal ideation by means of the suicidal item of the PHQ-9. [67] [44] Hyland et al. adapted three items from the 2014 English Adult Psychiatric Morbidity Survey to measure suicidal and self‐harm ideation [65]. On the other hand, Hao et al. assessed suicide ideation by means of a structured questionnaire [60]. In the Australian study conducted in the Victoria region, authors collected data that included both past-month passive suicidal ideation (i.e., wished to be dead) and past-month serious suicidal ideation [64]. Admission book data and information from bedhead tickets were used in the Sri Lanka study to identify self-poisoning cases [68]. McDowell et al. gained data about the eventual presence or absence of suicidal ideation by reading psychiatric consultation notes [66]. Almost half of the studies found no correlation between previous mental health diagnoses and suicide behavior rate changes during the pandemic. For instance, Knipe et al. observed a drop in rates of ER presentation for self-poisoning during the pandemic period, but no statistical evidence that may correlate this difference with a pre-existing psychiatric condition was found [68]. Conversely, Czeisler et al. stated that the presence of a previously diagnosed psychiatric disorder was usually associated with poorer outcomes, including suicidal ideation, during the COVID-19 pandemic [69]. Louie et al. concluded that adults with Late-Life Depression (LLD) showed a significantly higher suicidal risk during the COVID-19 pandemic [61]. Moreover, in the study by Hyland et al., several different variables associated with suicide attempts were identified, including having received treatment for a mental health disorder. Interestingly, the same study demonstrated that patients treated for mental health problems display a higher risk of engaging in NSSI when compared to people with no psychiatric history [65]. Regarding presentations of patients with a substance use disorder (SUD), there was a differential increase during the COVID-19 period that might explain the rise in suicidal ideation presentations, according to McDowell et al. Olliè et al. demonstrating how daily virtual contacts were protective factors against suicidal ideation during the first French lockdown [66], 44. For specifics about these studies, see Table 5.

Conclusions, implications, and future directions

This study aims to provide an overview of studies investigating the relationship between suicide and COVID-19 in subjects with a pre-existing mental disorder. Results suggest that suffering from a mental disorder is a risk factor for suicidal behavior, especially during the pandemic. Some studies have also highlighted an increase in suicidal behavior that could be potentially addressable to the pandemic advent in people already affected by a psychiatric disorder. Precise diagnosis data were not clearly identifiable; however, Major Depressive Disorder outstands as a major risk factor for suicidal behavior [70], especially during the pandemic. Other psychopathological elements that stand out as risk factors for suicidality in this context are social isolation, complicated grief or loss of loved ones, loneliness, economic issues, decreased accessibility to mental health facilities, substance use disorders, alcohol abuse, autism spectrum disorder (ASD), PTSD, anxiety, fear of infection and SARS-CoV2 infection or COVID-19 disease [8, 19,20,21, 23,24,25, 28, 31,32,33,34, 37, 39, 40, 47, 49, 51, 52, 56, 63, 66]. Conversely, although most studies suggested an increase in suicidal behavior, presumably addressable to the advent of COVID-19 pandemic, disease or infection, in patients with a mental disorder, several of the works analyzed provided controversial data. Different studies did not clearly correlate mental illness and suicide risk during the pandemic but rather described the increase in suicidal behavior as a new-onset phenomenon. Although it is of utmost importance to consider that the results of the studies have several limitations; many studies included were carried out employing a cross-sectional method and could not address a direct causal relationship between suicide and COVID-19. The lack of longitudinal studies, especially on subjects with a pre-existing psychiatric condition, stands out as a limitation in obtaining specific and clarifying data. Another major inherent limitation is the reliance of most of the studies on a retrospective self-report assessment of changes in suicidal behavior. Many studies used item 9 of the Patient Health Questionnaire (PHQ) to evaluate suicide risk, which has already been shown as an insufficient assessment tool for suicide risk and ideation [71]. Moreover, a complete suicide evaluation was rarely carried out, and not all studies provided data obtained in a clinical setting. Finally, the majority of the selected studies focused on the general population, and most of the data on diagnosis was self-reported. Longitudinal studies with homogeneous samples focusing on subjects with an established diagnosis and carrying out a comprehensive physician-provided suicide assessment could yield better knowledge on this topic. Furthermore, a suicide assessment with suicide-focused scales is necessary. In conclusion, future multicenter studies with large population samples could clarify cross-country differences in suicidal behavior and risk in individuals with mental disorders.

Availability of data and materials

All data generated or analyzed during this study are included in this published article [and its additional information files].

References

Worldometers. https://www.worldometers.info/coronavirus/ Accessed 19 April 2022.

Bachmann S. Epidemiology of suicide and the psychiatric perspective. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2018;15:1425.

Wasserman IM. The impact of epidemic, war, prohibition and media on suicide: United States, 1910–1920. Suicide Life Threat Behav. 1992;22(2):240–54.

Cheung YT, Chau PH, Yip PS. A revisit on older adults suicides and severe acute respiratory syndrome (SARS) epidemic in Hong Kong. Int J Geriatr Psychiatry. 2008;23(12):1231–8. https://doi.org/10.1002/gps.2056. (PMID: 18500689).

Serafini G, Parmigiani B, Amerio A, Aguglia A, Sher L, Amore M. The psychological impact of COVID-19 on the mental health in the general population. QJM. 2020;113(8):531–7. https://doi.org/10.1093/qjmed/hcaa201.

Brooks SK, Webster RK, Smith LE, Woodland L, Wessely S, Greenberg N, Rubin GJ. The psychological impact of quarantine and how to reduce it: rapid review of the evidence. Lancet. 2020;395(10227):912–20. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0140-6736(20)30460-8.

Nordt C, Warnke I, Seifritz E, Kawohl W. Modelling suicide and unemployment: a longitudinal analysis covering 63 countries, 2000–11. Lancet Psychiatry. 2015;2(3):239–45. https://doi.org/10.1016/S2215-0366(14)00118-7.

Almaghrebi AH. Risk factors for attempting suicide during the COVID-19 lockdown: identification of the high-risk groups. J Taibah Univ Med Sci. 2021;16(4):605–11. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jtumed.2021.04.010.

Dsouza DD, Quadros S, Hyderabadwala ZJ, Mamun MA. Aggregated COVID-19 suicide incidences in India: fear of COVID-19 infection is the prominent causative factor. Psychiatry Res. 2020;290:113145. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.psychres.2020.113145.

Telles-Garcia N, Zahrli T, Aggarwal G, Bansal S, Richards L, Aggarwal S. Suicide attempt as the presenting symptom in a patient with COVID-19: a case report from the United States. Case Rep Psychiatry. 2020;2020:8897454.

McAndrew J, O’Leary J, Cotter D, Cannon M, MacHale S, Murphy KC, Barry H. Impact of initial COVID-19 restrictions on psychiatry presentations to the emergency department of a large academic teaching hospital. Ir J Psychol Med. 2021;38(2):108–15. https://doi.org/10.1017/ipm.2020.115.

Chatterjee, S. S., Barikar C, M., & Mukherjee, A. (2020). Impact of COVID-19 pandemic on pre-existing mental health problems. Asian J Psychiatry. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ajp.2020.102071.

Travis-Lumer Y, Kodesh A, Goldberg Y, Frangou S, Levine SZ. Attempted suicide rates before and during the COVID-19 pandemic: interrupted time series analysis of a nationally representative sample. Psychol Med. 2021;19:1–7. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0033291721004384.

Dubé JP, Smith MM, Sherry SB, Hewitt PL, Stewart SH. Suicide behaviors during the COVID-19 pandemic: a meta-analysis of 54 studies. Psychiatry Res. 2021;301:113998. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.psychres.2021.113998.

Tricco AC, Lillie E, Zarin W, O’Brien KK, Colquhoun H, Levac D, Moher D, Peters MDJ, Horsley T, Weeks L, Hempel S, Akl EA, Chang C, McGowan J, Stewart L, Hartling L, Aldcroft A, Wilson MG, Garritty C, Lewin S, Godfrey CM, Macdonald MT, Langlois EV, Soares-Weiser K, Moriarty J, Clifford T, Tunçalp Ö, Straus SE. PRISMA extension for scoping reviews (PRISMA-ScR): checklist and explanation. Ann Intern Med. 2018;169(7):467–73. https://doi.org/10.7326/M18-0850.

Munn Z, Peters MDJ, Stern C, Tufanaru C, McArthur A, Aromataris E. Systematic review or scoping review? Guidance for authors when choosing between a systematic or scoping review approach. BMC Med Res Methodol. 2018;18(1):143. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12874-018-0611-x.PMID.

WHO Director-General’s opening remarks at the media briefing on COVID19 -March 2020.

Arksey H, O’Malley L. Scoping studies: towards a methodological framework. Int J Soc Res Methodol. 2005;8(1):4–18.

Khosravani V, Samimi Ardestani SM, Sharifi Bastan F, McKay D, Asmundson GJG. The associations of obsessive-compulsive symptom dimensions and general severity with suicidal ideation in patients with obsessive-compulsive disorder: the role of specific stress responses to COVID-19. Clin Psychol Psychother. 2021;28(6):1391–402. https://doi.org/10.1002/cpp.2602.

Alonso P, Bertolín S, Segalàs J, Tubío-Fungueiriño M, Real E, Mar-Barrutia L, Fernández-Prieto M, Carvalho S, Carracedo A, Menchón JM. How is COVID-19 affecting patients with obsessive-compulsive disorder? A longitudinal study on the initial phase of the pandemic in a Spanish cohort. Eur Psychiatry. 2021;64(1):e45. https://doi.org/10.1192/j.eurpsy.2021.2214.

Na PJ, Tsai J, Hill ML, Nichter B, Norman SB, Southwick SM, Pietrzak RH. Prevalence, risk and protective factors associated with suicidal ideation during the COVID-19 pandemic in U.S. military veterans with pre-existing psychiatric conditions. J Psychiatr Res. 2021;137:351–9. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jpsychires.2021.03.021.

Rømer TB, Christensen RHB, Blomberg SN, Folke F, Christensen HC, Benros ME. Psychiatric admissions, referrals, and suicidal behavior before and during the COVID-19 pandemic in Denmark: a time-trend study. Acta Psychiatr Scand. 2021;144(6):553–62. https://doi.org/10.1111/acps.13369.

Fountoulakis KN, Apostolidou MK, Atsiova MB, Filippidou AK, Florou AK, Gousiou DS, Katsara AR, Mantzari SN, Padouva-Markoulaki M, Papatriantafyllou EI, Sacharidi PI, Tonia AI, Tsagalidou EG, Zymara VP, Prezerakos PE, Koupidis SA, Fountoulakis NK, Chrousos GP. Self-reported changes in anxiety, depression and suicidality during the COVID-19 lockdown in Greece. J Affect Disord. 2021;15(279):624–9. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jad.2020.10.061.

Nichter B, Hill ML, Na PJ, Kline AC, Norman SB, Krystal JH, Southwick SM, Pietrzak RH. Prevalence and trends in suicidal behavior among US military veterans during the COVID-19 pandemic. JAMA Psychiat. 2021;78(11):1218–27. https://doi.org/10.1001/jamapsychiatry.2021.2332.PMID:34431973;PMCID:PMC8387942.

Na P, Tsai J, Harpaz-Rotem I, Pietrzak R. Mental health and suicidal ideation in US military veterans with histories of COVID-19 infection. BMJ Mil Health. 2022 Feb;168(1):15–19. doi: https://doi.org/10.1136/bmjmilitary-2021-001846. Epub 2021 May 25. PMID: 34035155; PMCID: PMC8154290.

Batterham PJ, Calear AL, Shou Y, Farrer LM, Gulliver A, McCallum SM, Dawel A. Effects of the COVID-19 pandemic on suicidal ideation in a representative Australian population sample-Longitudinal cohort study. J Affect Disord. 2022;1(300):385–91. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jad.2022.01.022.

Fountoulakis KN, Karakatsoulis G, Abraham S, Adorjan K, Ahmed HU, Alarcón RD, Arai K, Auwal SS, Berk M, Bjedov S, Bobes J, Bobes-Bascaran T, Bourgin-Duchesnay J, Bredicean CA, Bukelskis L, Burkadze A, Abud IIC, Castilla-Puentes R, Cetkovich M, Colon-Rivera H, Corral R, Cortez-Vergara C, Crepin P, De Berardis D, Zamora Delgado S, De Lucena D, De Sousa A, Stefano RD, Dodd S, Elek LP, Elissa A, Erdelyi-Hamza B, Erzin G, Etchevers MJ, Falkai P, Farcas A, Fedotov I, Filatova V, Fountoulakis NK, Frankova I, Franza F, Frias P, Galako T, Garay CJ, Garcia-Álvarez L, García-Portilla MP, Gonda X, Gondek TM, González DM, Gould H, Grandinetti P, Grau A, Groudeva V, Hagin M, Harada T, Hasan MT, Hashim NA, Hilbig J, Hossain S, Iakimova R, Ibrahim M, Iftene F, Ignatenko Y, Irarrazaval M, Ismail Z, Ismayilova J, Jacobs A, Jakovljević M, Jakšić N, Javed A, Kafali HY, Karia S, Kazakova O, Khalifa D, Khaustova O, Koh S, Kopishinskaia S, Kosenko K, Koupidis SA, Kovacs I, Kulig B, Lalljee A, Liewig J, Majid A, Malashonkova E, Malik K, Malik NI, Mammadzada G, Mandalia B, Marazziti D, Marčinko D, Martinez S, Matiekus E, Mejia G, Memon RS, Martínez XEM, Mickevičiūtė D, Milev R, Mohammed M, Molina-López A, Morozov P, Muhammad NS, Mustač F, Naor MS, Nassieb A, Navickas A, Okasha T, Pandova M, Panfil AL, Panteleeva L, Papava I, Patsali ME, Pavlichenko A, Pejuskovic B, Pinto Da Costa M, Popkov M, Popovic D, Raduan NJN, Ramírez FV, Rancans E, Razali S, Rebok F, Rewekant A, Flores ENR, Rivera-Encinas MT, Saiz P, de Carmona MS, Martínez DS, Saw JA, Saygili G, Schneidereit P, Shah B, Shirasaka T, Silagadze K, Sitanggang S, Skugarevsky O, Spikina A, Mahalingappa SS, Stoyanova M, Szczegielniak A, Tamasan SC, Tavormina G, Tavormina MGM, Theodorakis PN, Tohen M, Tsapakis EM, Tukhvatullina D, Ullah I, Vaidya R, Vega-Dienstmaier JM, Vrublevska J, Vukovic O, Vysotska O, Widiasih N, Yashikhina A, Prezerakos PE, Smirnova D. Results of the COVID-19 mental health international for the general population (COMET-G) study. Eur Neuropsychopharmacol. 2022;54:21–40. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.euroneuro.2021.10.004.

Liu R, Xu X, Zou S, Li Y, Wang H, Yan X, Du X, Zhang L, Zhang Q, Li W, Cheung T, Ungvari GS, Ng CH, Xiang YT. Prevalence of suicidality and its association with quality of life in older patients with clinically stable psychiatric disorders in China during the COVID-19 pandemic. J Geriatr Psychiatry Neurol. 2022;35(2):237–44. https://doi.org/10.1177/08919887221078557.PMID:35246000;PMCID:PMC8899831.

Montalbani B, Bargagna P, Mastrangelo M, Sarubbi S, Imbastaro B, De Luca GP, Anibaldi G, Erbuto D, Pompili M, Comparelli A. The COVID-19 outbreak and subjects with mental disorders who presented to an Italian psychiatric emergency department. J Nerv Ment Dis. 2021;209(4):246–50. https://doi.org/10.1097/NMD.0000000000001289.

Berardelli I, Sarubbi S, Rogante E, Cifrodelli M, Erbuto D, Innamorati M, Lester D, Pompili M. The impact of the COVID-19 pandemic on suicide ideation and suicide attempts in a sample of psychiatric inpatients. Psychiatry Res. 2021;303:114072. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.psychres.2021.114072.

Kang JH, Lee SW, Ji JG, Yu JK, Jang YD, Kim SJ, Kim YW. Changes in the pattern of suicide attempters visiting the emergency room after COVID-19 pandemic: an observational cross-sectional study. BMC Psychiatry. 2021;21(1):571. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12888-021-03570-y.PMID:34781918;PMCID:PMC8591586.

Lee J, Kim D, Lee WJ, Woo SH, Jeong S, Kim SH. Association of the COVID-19 pandemic and low-rescue suicide attempts in patients visiting the emergency department after attempting suicide. J Korean Med Sci. 2021;36(34):e243. https://doi.org/10.3346/jkms.2021.36.e243.

Mutlu E, Anıl Yağcıoğlu AE. Relapse in patients with serious mental disorders during the COVID-19 outbreak: a retrospective chart review from a community mental health center. Eur Arch Psychiatry Clin Neurosci. 2021;271(2):381–3. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00406-020-01203-1.

Seifert J, Meissner C, Birkenstock A, Bleich S, Toto S, Ihlefeld C, Zindler T. Peripandemic psychiatric emergencies: impact of the COVID-19 pandemic on patients according to diagnostic subgroup. Eur Arch Psychiatry Clin Neurosci. 2021;271(2):259–70. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00406-020-01228-6.

Grossman MN, Fry CE, Sorg E, MacLean RL, Nisavic M, McDowell MJ, Masaki C, Bird S, Smith F, Beach SR. Trends in suicidal ideation in an emergency department during COVID-19. J Psychosom Res. 2021;150:110619. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jpsychores.2021.110619.

Ridout KK, Alavi M, Ridout SJ, Koshy MT, Awsare S, Harris B, Vinson DR, Weisner CM, Sterling S, Iturralde E. Emergency department encounters among youth with suicidal thoughts or behaviors during the COVID-19 pandemic. JAMA Psychiat. 2021;78(12):1319–28. https://doi.org/10.1001/jamapsychiatry.2021.2457.PMID:34468724;PMCID:PMC8411357.

Jefsen OH, Rohde C, Nørremark B, Østergaard SD. COVID-19-related self-harm and suicidality among individuals with mental disorders. Acta Psychiatr Scand. 2020;142(2):152–3. https://doi.org/10.1111/acps.13214.

Menculini G, Moretti P, Pandolfi LM, Bianchi S, Valentini E, Gatto M, Amantini K, Tortorella A. Suicidality and COVID-19: data from an emergency setting in Italy. Psychiatr Danub. 2021;33(Suppl 9):158–63 (PMID: 34559796).

Mortier P, Vilagut G, Ferrer M, Serra C, Molina JD, López-Fresneña N, Puig T, Pelayo-Terán JM, Pijoan JI, Emparanza JI, Espuga M, Plana N, González-Pinto A, Ortí-Lucas RM, de Salázar AM, Rius C, Aragonès E, Del Cura-González I, Aragón-Peña A, Campos M, Parellada M, Pérez-Zapata A, Forjaz MJ, Sanz F, Haro JM, Vieta E, Pérez-Solà V, Kessler RC, Bruffaerts R, Alonso J, MINDCOVID Working group. Thirty-day suicidal thoughts and behaviors among hospital workers during the first wave of the Spain COVID-19 outbreak. Depress Anxiety. 2021;38(5):528–44. https://doi.org/10.1002/da.23129.

Al-Humadi S, Bronson B, Muhlrad S, Paulus M, Hong H, Cáceda R. Depression, Suicidal Thoughts, and Burnout Among Physicians During the COVID-19 Pandemic: a Survey-Based Cross-Sectional Study. Acad Psychiatry. 2021;45(5):557–65.

Bruffaerts R, Voorspoels W, Jansen L, Kessler RC, Mortier P, Vilagut G, De Vocht J, Alonso J. Suicidality among healthcare professionals during the first COVID19 wave. J Affect Disord. 2021;15(283):66–70. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jad.2021.01.013.

Mamun MA, Syed NK, Griffiths MD. Indian celebrity suicides before and during the COVID-19 pandemic and their associated risk factors: evidence from media reports. J Psychiatr Res. 2020;131:177–9. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jpsychires.2020.09.002.

Panigrahi M, Pattnaik JI, Padhy SK, Menon V, Patra S, Rina K, Padhy SS, Patro B. COVID-19 and suicides in India: a pilot study of reports in the media and scientific literature. Asian J Psychiatr. 2021;57:102560. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ajp.2021.102560.

Olié E, Dubois J, Benramdane M, Guillaume S, Courtet P. Psychological state of a sample of patients with mood disorders during the first French COVID-19 lockdown. Sci Rep. 2021;11(1):23711. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-021-03037-w.PMID:34887481;PMCID:PMC8660817.

Behera C, Gupta SK, Singh S, Balhara YPS. Trends in deaths attributable to suicide during COVID-19 pandemic and its association with alcohol use and mental disorders: Findings from autopsies conducted in two districts of India. Asian J Psychiatr. 2021;58:102597. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ajp.2021.102597.

Mortier P, Vilagut G, Ferrer M, Alayo I, Bruffaerts R, Cristóbal-Narváez P, Del Cura-González I, Domènech-Abella J, Felez-Nobrega M, Olaya B, Pijoan JI, Vieta E, Pérez-Solà V, Kessler RC, Haro JM, Alonso J, MINDCOVID Working group. Thirty-day suicidal thoughts and behaviours in the Spanish adult general population during the first wave of the Spain COVID-19 pandemic. Epidemiol Psychiatr Sci. 2021;30:e19. https://doi.org/10.1017/S2045796021000093.

Sáiz PA, de la Fuente-Tomas L, García-Alvarez L, Bobes-Bascarán MT, Moya-Lacasa C, García-Portilla MP, Bobes J. Prevalence of Passive Suicidal Ideation in the Early Stage of the Coronavirus Disease 2019 (COVID-19) Pandemic and Lockdown in a Large Spanish Sample. J Clin Psychiatry. 2020.

Sáiz PA, Dal Santo F, García-Alvarez L, Bobes-Bascarán MT, Jiménez-Treviño L, Seijo-Zazo E, Rodríguez-Revuelta J, González-Blanco L, García-Portilla MP, Bobes J. Suicidal ideation trends and associated factors in different large Spanish samples during the first year of the COVID-19 pandemic. J Clin Psychiatry. 2022;83(2):21br14061. https://doi.org/10.4088/JCP.21br14061.

Wathelet M, Duhem S, Vaiva G, et al. Factors associated with mental health disorders among university students in France confined during the COVID-19 pandemic. JAMA Netw Open. 2020;3(10):e2025591. https://doi.org/10.1001/jamanetworkopen.2020.25591.

López Steinmetz LC, Dutto Florio MA, Leyes CA, Fong SB, Rigalli A, Godoy JC. Levels and predictors of depression, anxiety, and suicidal risk during COVID-19 pandemic in Argentina: the impacts of quarantine extensions on mental health state. Psychol Health Med. 2022;27(1):13–29. https://doi.org/10.1080/13548506.2020.

Vrublevska J, Sibalova A, Aleskere I, Rezgale B, Smirnova D, Fountoulakis KN, Rancans E. Factors related to depression, distress, and self-reported changes in anxiety, depression, and suicidal thoughts during the COVID-19 state of emergency in Latvia. Nord J Psychiatry. 2021;75(8):614–23. https://doi.org/10.1080/08039488.2021.

Papadopoulou A, Efstathiou V, Yotsidi V, Pomini V, Michopoulos I, Markopoulou E, Papadopoulou M, Tsigkaropoulou E, Kalemi G, Tournikioti K, Douzenis A, Gournellis R. Suicidal ideation during COVID-19 lockdown in Greece: prevalence in the community, risk and protective factors. Psychiatry Res. 2021;297:113713. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.psychres.2021.113713.

Shi L, Que JY, Lu ZA, Gong YM, Liu L, Wang YH, Ran MS, Ravindran N, Ravindran AV, Fazel S, Bao YP, Shi J, Lu L. Prevalence and correlates of suicidal ideation among the general population in China during the COVID-19 pandemic. Eur Psychiatry. 2021;64(1):e18. https://doi.org/10.1192/j.eurpsy.2021.5.

Iob E, Steptoe A, Fancourt D. Abuse, self-harm and suicidal ideation in the UK during the COVID-19 pandemic. Br J Psychiatry. 2020;217(4):543–6. https://doi.org/10.1192/bjp.2020.130.PMID:32654678;PMCID:PMC7360935.

Kasal A, Kuklová M, Kågström A, Winkler P, Formánek T. Suicide risk in individuals with and without mental disorders before and during the COVID-19 pandemic: an analysis of three nationwide cross-sectional surveys in Czechia. Arch Suicide Res. 2022;24:1–15. https://doi.org/10.1080/13811118.2022.2051653.

Sasaki N, Tabuchi T, Okubo R, Ishimaru T, Kataoka M, Nishi D. Temporary employment and suicidal ideation in COVID-19 pandemic in Japan: a cross-sectional nationwide survey. J Occup Health. 2022;64(1):e12319. https://doi.org/10.1002/1348-9585.12319.

Every-Palmer S, Jenkins M, Gendall P, et al. Psychological distress, anxiety, family violence, suicidality, and wellbeing in New Zealand during the COVID-19 lockdown: A cross-sectional study. PLoS ONE. 2020;15(11):e0241658. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0241658.

Daly Z, Slemon A, Richardson CG, Salway T, McAuliffe C, Gadermann AM, Thomson KC, Hirani S, Jenkins EK. Associations between periods of COVID-19 quarantine and mental health in Canada. Psychiatry Res. 2021;295:113631. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.psychres.2020.113631.

Veldhuis CB, Nesoff ED, McKowen ALW, Rice DR, Ghoneima H, Wootton AR, Papautsky EL, Arigo D, Goldberg S, Anderson JC. Addressing the critical need for long-term mental health data during the COVID-19 pandemic: changes in mental health from april to september 2020. Prev Med. 2021;146:106465. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ypmed.2021.106465.

Hao F, Tan W, Jiang L, Zhang L, Zhao X, Zou Y, Hu Y, Luo X, Jiang X, McIntyre RS, Tran B, Sun J, Zhang Z, Ho R, Ho C, Tam W. Do psychiatric patients experience more psychiatric symptoms during COVID-19 pandemic and lockdown? A case-control study with service and research implications for immunopsychiatry. Brain Behav Immun. 2020;87:100–6. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.bbi.2020.04.069.

Louie LLC, Chan WC, Cheng CPW. Suicidal risk in older patients with depression during COVID-19 pandemic: a case-control study. East Asian Arch Psychiatry. 2021;31(1):3–8. https://doi.org/10.12809/eaap2055.

Carlin GL, Baumgartner JS, Moftakhar T, König D, Negrin LL. Impact of COVID-19 lockdown on suicide attempts : a retrospective analysis of the springtime admissions to the trauma resuscitation room at the medical university of Vienna from 2015–2020. Wien Klin Wochenschr. 2021;133(17–18):915–22. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00508-021-01839-6.

Hedley D, Hayward SM, Denney K, Uljarević M, Bury S, Sahin E, Brown CM, Clapperton A, Dissanayake C, Robinson J, Trollor J, Stokes MA. The association between COVID-19, personal wellbeing, depression, and suicide risk factors in Australian autistic adults. Autism Res. 2021. https://doi.org/10.1002/aur.2614.

Czeisler MÉ, Lane RI, Petrosky E, Wiley JF, Christensen A, Njai R, Weaver MD, Robbins R, Facer-Childs ER, Barger LK, Czeisler CA, Howard ME, Rajaratnam SMW. Mental health, substance use, and suicidal ideation during the COVID-19 pandemic—United States, June 24–30, 2020. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2020;69(32):1049–57. https://doi.org/10.15585/mmwr.mm6932a1.PMID:32790653;PMCID:PMC7440121.

Hyland P, Rochford S, Munnelly A, Dodd P, Fox R, Vallières F, McBride O, Shevlin M, Bentall RP, Butter S, Karatzias T, Murphy J. Predicting risk along the suicidality continuum: A longitudinal, nationally representative study of the Irish population during the COVID-19 pandemic. Suicide Life Threat Behav. 2022;52(1):83–98. https://doi.org/10.1111/sltb.12783.

McDowell MJ, Fry CE, Nisavic M, Grossman M, Masaki C, Sorg E, Bird S, Smith F, Beach SR. Evaluating the association between COVID-19 and psychiatric presentations, suicidal ideation in an emergency department. PLoS ONE. 2021;16(6):e0253805. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0253805.

Hamm ME, Brown PJ, Karp JF, Lenard E, Cameron F, Dawdani A, Lavretsky H, Miller JP, Mulsant BH, Pham VT, Reynolds CF, Roose SP, Lenze EJ. Experiences of American older adults with pre-existing depression during the beginnings of the COVID-19 pandemic: a multicity mixed-methods study. Am J Geriatr Psychiatr. 2020;28(9):924–32. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jagp.2020.06.013.

Knipe D, Silva T, Aroos A, Senarathna L, Hettiarachchi NM, Galappaththi SR, Spittal MJ, Gunnell D, Metcalfe C, Rajapakse T. Hospital presentations for self-poisoning during COVID-19 in Sri Lanka: an interrupted time-series analysis. Lancet Psychiatry. 2021;8(10):892–900. https://doi.org/10.1016/S2215-0366(21)00242-X.

Czeisler MÉ, Wiley JF, Facer-Childs ER, Robbins R, Weaver MD, Barger LK, Czeisler CA, Howard ME, Rajaratnam SMW. Mental health, substance use, and suicidal ideation during a prolonged COVID-19-related lockdown in a region with low SARS-CoV-2 prevalence. J Psychiatr Res. 2021;140:533–44. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jpsychires.2021.05.080.

Bertolote JM, Fleischmann A. Suicide and psychiatric diagnosis: a worldwide perspective. World Psychiatr. 2002;1:181–5.

Na PJ, Yaramala SR, Kim JA, Kim H, Goes FS, Zandi PP, Vande Voort JL, Sutor B, Croarkin P, Bobo WV. The PHQ-9 Item 9 based screening for suicide risk: a validation study of the patient health questionnaire (PHQ)-9 Item 9 with the Columbia suicide severity rating scale (C-SSRS). J Affect Disord. 2018;232:34–40. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jad.2018.02.045.

Funding

None.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Conceptualization and design were performed by T.B., P.S., F.P., A.R and R.R. Data extraction was conducted by T.B. and verified by C.D.A. V.S. and R.D.S. screened citations for inclusion. T.B. and C.D.A. wrote the main manuscript text and S.M. and F.C. prepared Fig. 1 and Tables 1, 2, 3, 4 and 5. T.B., R.R., A.R. and F.P. developed methodology, formal analysis, and data curation. All authors contributed equally to the article. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate

Not applicable.

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/. The Creative Commons Public Domain Dedication waiver (http://creativecommons.org/publicdomain/zero/1.0/) applies to the data made available in this article, unless otherwise stated in a credit line to the data.

About this article

Cite this article

Barlattani, T., D’Amelio, C., Capelli, F. et al. Suicide and COVID-19: a rapid scoping review. Ann Gen Psychiatry 22, 10 (2023). https://doi.org/10.1186/s12991-023-00441-6

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/s12991-023-00441-6