Abstract

Background

Self-harm (SH) is among the strongest predictors of further episodes of SH, suicide attempt, and death by suicide. People who repeteadly harm themselves are at even higher risk for suicide. Factors influencing the repetition are important to identify when assessing suicidal risk and thereafter to offer specific interventions. Therefore, this study aimed to compare first versus multiple episodes characteristics in a large sample of patients in french-speaking Switzerland.

Method

We used the database from the French-speaking Swiss program for monitoring SH. Data of the psychiatric assessment of all adults admitted for SH were collected in the emergency department of four Swiss city hospitals between December 2016 and October 2019.

Results

1730 episodes of SH were included. Several variables were significantly associated with multiple episodes, including diagnosis (over representation of personality disorders and under representation of anxiety disorders), professional activity (Invalidity insurance more frequent) and prior psychiatry care.

Conclusions

Patients suffering from a personality disorder and those with invalidity insurance are at risk for multiple episodes of SH and should be targeted with specific interventions.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Together with suicide attempt (SA), self-harmFootnote 1 (SH) [1, 2] is one of the strongest predictors of further episodes of SA, SH and completed suicide [3,4,5,6,7]. Moreover, in themselves, SA and SH lead to costly hospitalization [8], stigma [9], and difficulties in asking for help [10]. Among persons who self-harm, those with multiple episodes are at higher risk of dying by suicide [11] and, thus, represent an important target for prevention [12]. Previous research sought to find differences between those who engage in a single episode of self-harm versus repeated episodes. Identifying factors influencing the repetition is important to include this information in the suicidal risk assessment and then to offer specific interventions targeting modifiable risk factors. Moreover, this can help to improve the care of patients who harm themselves.

A systematic review in 2013 showed that unemployment, unmarried status, diagnosis of mental disorders, suicidal ideation (SI), stressful life events, and family history of suicidal behavior were associated with repetition of SA in adults [12]. In young people, another systematic review identified any personality disorder and any mood disorder as modifiable risk factors, and severity of hopelessness, SI and previous sexual abuse as associated with repetition of SH [13]. Recent studies on adults with a prospective or cross-sectional design also found several risk factors for SA or SH repetition. They included any mental disorder, impulsivity, borderline personality disorder, PTSD, substance misuse, severity of psychopathology, lethality of SA, high SI, unmarried status, living alone, younger age, low social support, no occupation, previous psychiatric treatment, history of sucide or major depression in the family, hopelessness and physical illness [14,15,16,17,18,19,20,21,22]. Finally, childhood maltreatment and/or sexual abuse have been associated with suicidal behaviors in a systematic review [23] and with repetition in two prospective studies [24, 25].

These heteogeneous results may in part be explained by low statistical power, most of the studies including between 60 and 300 patients. Moreover, they may reflect the unconsistency of definitions of multiple suicide attempters/patients with multiple SH episodes and the fact that people with a first episode at one point may further become repeaters (e.g., people who repeatedly harm themselves) [12]. Finally, they are certainly also related to wide differences in repetition patterns depending on location and cultural contexts [26], a recent systematic review namely highlighting important geographical differences in repetition of fatal and non-fatal SH [27]. Studies on specific regions are, thus, necessary. We could not identify any study on repetition of SH in Switzerland and aimed to compare first versus multiple episodes characteristics in a large sample of patients in French-speaking Switzerland. Following the existing literature, we hypothesized that specific socio-demographic and/or clinical factors would be independantly associated with repetition in our sample. Among the investigated factors were variables related to age, gender, social and professional status, lifestyle but also physical and mental health and detailed characteristics of the SH episode.

Materials and methods

The French-speaking Swiss program for monitoring SH

For this study, we used the database from the French-speaking Swiss program for monitoring SH. This monitoring has been described in full details elsewhere [28]. Briefly, it aimed to collect systematically data during the psychiatric assessment of all patients admitted for SH in four emergency departments (ED) of Swiss general hospitals between December 2016 and November 2019.

Participants

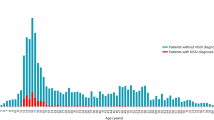

All patients 18 years of age or older and admitted for SH in the four ED were included in this study (inclusion criteria). Patients under 18 were exluded (exclusion criteria). Patients who appeared multiple times in the database and patients who reported having made previous episodes of SH were included in the multiple episodes group. Data of the last episode were used in this study. Patients who declared no prior episode were included in the first episode group. Patients who apperead once in the database but without information on previous episodes were excluded. 1730 participants (mean age = 38.2; SD = 15.2) were included.

Procedure

The data were based on information gathered through clinical evaluation by psychiatric residents [28]. Data were recorded through a paper form filled-in by the resident assessing the patient. The paper form [28] included items on socio-demographic characteristics (e.g., age, gender, nationality, problematic socioeconomic situation, migration in the past 10 years, civil status, invalidity insurance (pension for people who have been unable to work for health reasons into the working world.)) and clinical information (e.g., first International Classification of Diseases diagnosis (ICD-10) coded by sections (see Table 2), past history of self-harm, existing psychiatric illnesses, psychiatric history, existing follow-up) and detailed information on the patient's suicidal process (e.g., suicidal intent, method of self-harm and severity of the self-harm episode, protective and precipitating factors). Psychiatric diagnoses were recorded according to the ICD-10 under the supervision of senior psychiatrists; collectors could mention up to three diagnoses by order of importance [28]. Name, surname, gender and birth date were merged into one string and subjected to the Message Digest 5 algorithm (MD5) which creates a 128-bit cryptographic hash. This unique text string allowed us to ensure patient anonymity in the database while allowing us to identify participants with multiple episodes within one site or from one site to another.

Statistical analysis

Comparisons between groups were performed with independent t-tests for continuous variables and Pearson's Chi-Square tests (or Fisher Exact tests with exact or Monte-Carlo estimation when needed) for categorical variables. To highlight the most important variables independent of each other, a multivariate logistic model was estimated. Multiple Imputation was deemed not feasible given the very large proportion of nominal variables. Only variables with less than 15% of missing data and reaching a p < 0.05 level of significance when comparing the two groups were included as independent variables. All statistical analyses were performed with IBM-SPSS 26. All statistical tests were two tailed and significance was determined at the 0.05 level.

Results

Comparison of the socio-demographic variables (Table 1) showed that females (p = 0.005) and Swiss nationals (p = 0.014) were overrepresented in the multiple episodes group. Problematic socioeconomic situation (p < 0.001), living single lifestyle (p < 0.001), and single civil status (p < 0.001) were also more likely in the multiple episodes group. Examination of level of education revealed that patients of the multiple episodes group were also more likely to only have basic/elementary training (p < 0.001). Patients who made multiple episodes were more likely to be working part time or to benefit from the invalidity insurance (p < 0.001). They were also more likely to have another legal representative than themselves (p < 0.001). Considering clinical variables (Table 2), patients who made multiple episodes were less likely to have a diagnosis of anxiety/stress-related (F 4) disorder and more likely to have a diagnosis of personality disorder (p < 0.001). They were more likely to suffer from physical pain (p = 0.010) and/or physical illnesses (p = 0.040). Location at the time of SH was slightly less likely to be at home for patients with multiple episodes (p = 0.006). Patients of the multiple episodes group were less likely to arrive at the emergency departments with family or friends and more likely to arrive alone (p = 0.043). They were more often intoxicated at the time of the episode (p < 0.001) and use of any substance during the last 3 months was higher (p-values ranging between < 0.001 and 0.012). Considering existing follow-up at time of SH, patients with multiple episodes were less likely to have no follow-up and more likely to have psychiatric care (p < 0.001). Post-self-harm follow-up was less likely to be outpatient public psychiatry network and more likely to be a voluntary or involuntary psychiatric hospitalization (p < 0.001). Finally, significant events related to work situation (p = 0.004) or harassment/mobbing (p = 0.032) were less frequent for patients who had repeated episodes of SH.

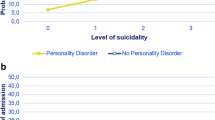

Results of the multivariate logistic model showed that only three variables remained significant when all variables were considered altogether. Diagnosis (Anxiety/stress-related F4 versus Depression F3-D as the reference category, Odds ratio = 0.508, p < 0.001; Personality disorder F6 versus Depression F3-D as the reference category, Odds ratio = 2.010, p = . 002), Professional activity (Invalidity Insurance versus Working full time as the reference category, Odds ratio = 2.174, p = 0.009) and Pre-self-harm episode follow-up (Outpatient public psychiatry network versus None, Odds ratio = 2.421, p < 0.001).

Discussion

Patients with multiple episodes of SH differed from those with a first episode on several variables. The most important ones were diagnosis (over representation of personality disorders and under representation of anxiety/stress-related disorders), professional activity (Invalidity insurance more frequent) and prior psychiatry care.

Regarding diagnosis, we found repeaters to suffer more frequently from a personality disorder. Our analyses did not differentiate between specific personality disorders but we had a high prevalence of the diagnosis of borderline personality disorder in our sample (62.01%; 222/358). It is, thus, likely that this result reflects a risk with borderline personality disorders, in line with the previous research showing borderline personality disorder or traits to be associated with repetition both in adults [15, 18, 22, 29] and in young people [13]. Persons with a borderline personality disorder should be offered specific treatment to reduce repetition, such as Dialectical Behavior Therapy [30], Mentalization-based treatment [31] or Transference-focused psychotherapy [32]. Interestingly, anxiety/stress-related disorder was found to be less frequent in repeaters, a result we did not find in previous studies. While the severity of psychopathology was found to be related to repetition [5, 22] and since an important proportion of our anxiety/stress-related disorders were adjustment disorders (75.63%; 329/435), we could suppose that adjustment disorder, a frequently used diagnosis [33], was more frequently made for patients with a less severe psychopathology. However, following the interpersonal theory of suicide [34, 35], this could also reflect a decrease in the anxiety level with the repetition of SH. Indeed, habituation and activation of adverse processes in response to repeated exposure to physically painful and/or fear-generating experiences reduce not only the fear of death but also physical anxiety.

Our results on occupation underline the importance of the social context for repetition of SH and is in line with previous findings on absence of occupation as a risk factor for repetition of SA [12, 21]. Since having an occupation is a major way to be and stay connected with people and to get support if needed, this result also echoes previous research showing that low social support is associated with repetition of SA [16, 19]. Furthermore, low social support is related to loneliness, which can increase interpersonal difficulties—both with relatives and with health care providers—in a vicious circle, and perceived burdensomeness—a risk factor for suicidal behavior [35, 36]—prevents repeaters from reporting their feelings and seeking help from peers and family. Clinicians should be aware of the specific issues related to interpersonal relationship, especially with patients suffering from a personality disorder [37]. The fact that, in unvariate analysis, patients with multiple episodes were more likely to present alone to the emergency departements may also be related to this low social support and this population requires special attention. At an individual level, when meeting suicidal patients, health professionals shoud consider social determinants as well as mental-health problems [38, 39]. Social difficulties should be targeted when elaborating a treatment plan: social workers should be included in the treatement and mobilization of social support has to be specifically adressed. At a population level, politics should be aware of the importance of having a job as a protective factor against repetition of SH, since SH also represents an important economic burden [8].

Interestingly, we found no difference between our two groups on the intent to die, recorded as absent, unclear or present. This differs from several studies [5, 19, 22] and a systematic review [12] showing repetition to be associated with the intensity of SI in suicide attempters. It may be that our group of multiple episodes include an important proportion of non-suicidal self-injury, thus mitigating this association.

Several other variables that were highlighted may deserve attention. While intoxication at the time of the SH and substance use were associated to repetition in univariate analysis, this did not remain significant in multivariate analysis. One study found men repeaters to use substance more frequently [20] and a study including veterans (probably mostly men) [18] identified substance use disorders as more frequent in repeaters. We did not perform a separate gender analysis but this negative result underscores the need of specific research on pattern of repetition across women and men. Finally and interestingly, age, realization of the self-harm episode, level of suicidal intent and seriousness of the episode did not differ between the two groups.

This study has several limitations. First, some variables had some non-ignorable amount of missing data and several significant variables were excluded from the multivariate regression model (recent significant events for work situation and harassment/mobbing, education and use of substance during the last three months). Second, it is likely that patients with a first episode of SH at one point may further become repeaters [12]. Third, this study is cross-sectional in design and longitudinal studies may be warranted to strengthen our findings.

Conclusion

Repeated SH represents a high risk for suicidal patients and monitoring SH is an important yet difficult endeavor. In our study, patients suffering from a personality disorder were at risk for multiple episodes of SH. Regarding individual actions, clinicians should be especially vigilant about these patients and offer them specific and dedicated interventions. With this population, they should also be aware of their own emotional reactions, which may hinder proper assessment and treatment through adverse countertransference [38, 39].

Our study also showed that people with invalidity insurance were more prone to repeat SH; this highlights the importance of the social context for suicidal behaviors. Obviously, further studies are needed to determine to which extent this could be partly accounted for by variables like public stigma and self-stigma. Regarding community responsibilities and policy implication, additional regulations are needed to warrant patients’ access to specialized care and adequate treatment, all the more so after factors associated with repetition have been identified. To reach this goal, studies on specific interventions (e.g., sustained social work, vocational interventions, and psychotherapeutic interventions) to reduce repetition are warranted. Awareness campaigns towards health professional from various backgrounds must also be developed in such a way that the risk factors are known and investigated.

Availability of data and materials

The datasets generated and analyzed during the current study are not publicly available because public archiving of data was not explicitly authorized by the ethic committee. Nevertheless, anonymous data are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

Notes

For this study, self-harm is defined as “all non-fatal intentional acts of self-poisoning or self-injury, irrespective of degree of suicidal intent or other types of motivation” [1], thus including both DSM 5 non-suicidal self-injury and other acts of self-harm with various suicidal intents, following a dimensional rather than categorical approach to the phenomenon [2].

References

Hawton K, Zahl D, Weatherall R. Suicide following deliberate self-harm: long-term follow-up of patients who presented to a general hospital. Br J Psychiatry. 2003;182:537–42. https://doi.org/10.1136/bmj.325.7374.1207.

World Health Organization. (2016). Practice manual for establishing and maintaining surveillance systems for suicide attempts and self-harm. Retrieved from http://apps.who.int/iris/bitstream/handle/10665/208895/9789241549578_eng.pdf;jsessionid=DB9894D3EC5DD66BE3521E9D66E8022C?sequence=1

Christiansen E, Frank Jensen B. Risk of repetition of suicide attempt, suicide or all deaths after an episode of attempted suicide: a register-based survival analysis. Aust N Z J Psychiatry. 2007;41(3):257–65. https://doi.org/10.1080/00048670601172749.

Geulayov G, Kapur N, Turnbull P, Clements C, Waters K, Ness J, Townsend E, Hawton K. Epidemiology and trends in non-fatal self-harm in three centres in England, 2000–2012: findings from the Multicentre Study of Self-harm in England. BMJ Open. 2016;6(4):e010538.

Owens D, Horrocks J, House A. Fatal and non-fatal repetition of self-harm. Systematic review Br J Psychiatry. 2002;181:193–9. https://doi.org/10.1192/bjp.181.3.193.

Suokas J, Suominen K, Isometsa E, Ostamo A, Lonnqvist J. Long-term risk factors for suicide mortality after attempted suicide: findings of a 14-year follow-up study. Acta Psychiatr Scand. 2001;104(2):117–21. https://doi.org/10.1034/j.1600-0447.2001.00243.x.

Suominen K, Isometsa E, Suokas J, Haukka J, Achte K, Lonnqvist J. Completed suicide after a suicide attempt: a 37-year follow-up study. Am J Psychiatry. 2004;161(3):562–3. https://doi.org/10.1176/appi.ajp.161.3.562.

Swiss Federal Office of Public Health. (2016). National action plan: preventing suicide in Switzerland. Retrieved from https://www.bag.admin.ch/dam/bag/en/dokumente/psychische-gesundheit/politische-auftraege/motion-ingold/bericht_suizidpr%C3%A4vention.pdf.download.pdf/Report%20Suicide%20prevention%20in%20Switzerland.pdf

Cvinar JG. Do suicide survivors suffer social stigma: a review of the literature. Perspect Psychiatr Care. 2005;41(1):14–21.

Han J, Batterham P, Calear A, Randall R. Factors influencing professional help-seeking for suicidality. Crisis. 2018;39(3):175–96. https://doi.org/10.1027/0227-5910/a000485.

Scoliers G, Portzky G, van Heeringen K, Audenaert K. Sociodemographic and psychopathological risk factors for repetition of attempted suicide: a 5-year follow-up study. Arch Suicide Res. 2009;13(3):201–13. https://doi.org/10.1080/13811110902835130.

Mendez-Bustos P, de Leon-Martinez V, Miret M, Baca-Garcia E, Lopez-Castroman J. Suicide reattempters: a systematic review. Harv Rev Psychiatry. 2013;21(6):281–95. https://doi.org/10.1097/HRP.0000000000000001.

Witt K, Milner A, Spittal MJ, Hetrick S, Robinson J, Pirkis J, Carter G. Population attributable risk of factors associated with the repetition of self-harm behaviour in young people presenting to clinical services: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Eur Child Adolesc Psychiatry. 2019;28(1):5–18. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00787-018-1111-6.

Berardelli I, Forte A, Innamorati M, Imbastaro B, Montalbani B, Sarubbi S, De Luca GP, Mastrangelo M, Anibaldi G, Rogante E, Lester D, Denise E, Gianluca S, Mario A, Pompili M. Clinical differences between single and multiple suicide attempters, suicide ideators, and non-suicidal inpatients. Front Psychiatry. 2020. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyt.2020.605140.

Boisseau CL, Yen S, Markowitz JC, Grilo CM, Sanislow CA, Shea MT, Zanarini MC, Skodol AE, Gunderson JG, Morey LC, McGlashan TH. Individuals with single versus multiple suicide attempts over 10 years of prospective follow-up. Compr Psychiatry. 2013;54(3):238–42.

Choi KH, Wang SM, Yeon B, Suh SY, Oh Y, Lee HK, Kweon YS, Lee CT, Lee KU. Risk and protective factors predicting multiple suicide attempts. Psychiatry Res. 2013;210(3):957–61.

Kawahara YY, Hashimoto S, Harada M, Sugiyama D, Yamada S, Kitada M, Sakurai T, Takahashi T, Yamashita K, Watanabe K, Mimura M. Predictors of short-term repetition of self-harm among patients admitted to an emergency room following self-harm: A retrospective one-year cohort study. Psychiatry Res. 2017;1(258):421–6.

Kochanski KM, Lee-Tauler SY, Brown GK, Beck AT, Perera KU, Novak L, LaCroix JM, Lento RM, Ghahramanlou-Holloway M. Single versus multiple suicide attempts: a prospective examination of psychiatric factors and wish to die/wish to live index among military and civilian psychiatrically admitted patients. J Nerv Ment Dis. 2018;206(8):657–61.

Liu Y, Zhang J, Sun L. Who are likely to attempt suicide again? A comparative study between the first and multiple timers. Compr Psychiatry. 2017;78:54–60.

Monnin J, Thiemard E, Vandel P, Nicolier M, Tio G, Courtet P, Bellivier F, Sechter D, Haffen E. Sociodemographic and psychopathological risk factors in repeated suicide attempts: gender differences in a prospective study. J Affect Disord. 2012;136(1–2):35–43.

Perquier F, Duroy D, Oudinet C, Maamar A, Choquet C, Casalino E, Lejoyeux M. Suicide attempters examined in a Parisian Emergency Department: Contrasting characteristics associated with multiple suicide attempts or with the motive to die. Psychiatry Res. 2017;253:142–9.

Sher, L., Grunebaum, M. F., Burke, A. K., Chaudhury, S., Mann, J. J., & Oquendo, M. A. (2017). Depressed Multiple-SuicideAttempters–A High-Risk Phenotype. Crisis.

Serafini G, Canepa G, Adavastro G, Nebbia J, Belvederi Murri M, Erbuto D, Pocai B, Fiorillo A, Pompili M, Flouri E, Amore M. The relationship between childhood maltreatment and non-suicidal self-injury: a systematic review. Front Psych. 2017;24(8):149. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyt.2017.00149.

Haw C, Bergen H, Casey D, Hawton K. Repetition of deliberate self-harm: A study of the characteristics and subsequent deaths in patients presenting to a general hospital according to extent of repetition. Suicide LifeThreatening Behavior. 2007;37(4):379–96. https://doi.org/10.1521/suli.2007.37.4.379.

Hjelmeland H. Repetition of parasuicide: a predictive study. Suicide Life Threat Behav. 1996;26(4):395–404.

Harriss L, Hawton K. Deliberate self-harm in rural and urban regions: a comparative study of prevalence and patient characteristics. Soc Sci Med. 2011;73(2):274–81. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.socscimed.2011.05.011.

Liu B-P, Lunde KB, Jia C-X, Qin P. The short-term rate of non-fatal and fatal repetition of deliberate self-harm: A systematic review and meta-analysis of longitudinal studies. J Affect Disord. 2020;273:597–603. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jad.2020.05.072.

Ostertag L, Golay P, Dorogi Y, Brovelli S, Bertran M, Cromec I, Van Der Vaeren B, Khan RA, Costanza A, Wyss K, Edan A. The implementation and first insights of the French-speaking Swiss programme for monitoring self-harm. Swiss Med Wkly. 2019. https://doi.org/10.4414/smw.2019.20016.

Stringer B, van Meijel B, Eikelenboom M, Koekkoek B, Licht CM, Kerkhof AJ, Penninx BW, Beekman AT. Recurrent suicide attempts in patients with depressive and anxiety disorders: the role of borderline personality traits. J Affect Disord. 2013;151(1):23–30. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jad.2013.02.038.

Neacsiu AD, Bohus M, Linehan MM. Dialectical behavior therapy: An intervention for emotion dysregulation. In: Handbook of emotion regulation. 2nd ed. New York, NY: Guilford Press; US; 2014. p. 491–507.

Bateman AW, Fonagy P. Mentalization-based treatment of BPD. J Pers Disord. 2004;18(1):36–51.

Kernberg OF. New developments in transference focused psychotherapy. Int J Psychoanal. 2016;97(2):385–407. https://doi.org/10.1111/1745-8315.12289.

Weber G, Michaud L, Weber O, Stiefel F, Krenz S. Remission factors of adjustment disorders: The patients’ view. A qualitative study. Ann Méd-Psychol. 2018. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.amp.2017.10.012.

Baertschi M, Costanza A, Richard-Lepouriel H, Pompili M, Sarasin F, Weber K, Canuto A. The application of the interpersonal-psychological theory of suicide to a sample of Swiss patients attending a psychiatric emergency department for a non-lethal suicidal event. J Affect Disord. 2017;210:323–31.

Van Orden KA, Witte TK, Cukrowicz KC, Braithwaite SR, Selby EA, Joiner TE Jr. The interpersonal theory of suicide. Psychol Rev. 2010;117(2):575–600. https://doi.org/10.1037/a0018697.

Chu C, Buchman-Schmitt JM, Stanley IH, Hom MA, Tucker RP, Hagan CR, Joiner TE Jr. The interpersonal theory of suicide: A systematic review and meta-analysis of a decade of cross-national research. Psychol Bull. 2017;143(12):1313–45. https://doi.org/10.1037/bul0000123.

Michaud L, Ligier F, Bourquin C, Corbeil S, Saraga M, Stiefel F, Seguin M, Turecki G, Richard-Devantoy S. Differences and similarities in instant counter transference towards patients with suicidal ideation and personality disorders. J Affect Disord. 2020;15(265):669–78. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jad.2019.11.115

Michaud L, Dorogi Y, Gilbert S, Bourquin C. Patient perspectives on an intervention after suicide attempt: The need for patient centred and individualized care. PLoS ONE. 2021;16(2):e0247393. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0247393.

Michaud L, Greenway KT, Corbeil S, Bourquin C, Richard-Devantoy S. Countertransference towards suicidal patients: a systematic review. Curr Psychol. 2021. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12144-021-01424-0.

Acknowledgements

The authors would like to thank all clinicians involved in the psychiatric assessment of the patients.

Funding

This study was based on institutional funding and funded by the Swiss Federal Office of Public Health.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

PG, LO, SS and LM made substantial contributions to the conception and design of the study. LO, SS, AC, BV, YD, SS and LM made substantial contributions the acquisition, analysis, and interpretation of the data. PG, LO, SS and LM drafted the work and substantively revised it. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate

This study was conducted without the explicit consent of patients. This issue was given full consideration and the relevant cantonal ethic committees on human research approved the project (Human Research Ethics Committee of the Canton Vaud protocol (Cantonal ethic committees on human research (CER-VD) approved the project (no. 2016–01489). We argued that requesting consent would have introduced a selection bias. All methods were carried out in accordance with the recommendations of the Human Research Ethics Committee of the Canton Vaud and the Declaration of Helsinki.

Consent for publication

Not Applicable.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/. The Creative Commons Public Domain Dedication waiver (http://creativecommons.org/publicdomain/zero/1.0/) applies to the data made available in this article, unless otherwise stated in a credit line to the data.

About this article

Cite this article

Golay, P., Ostertag, L., Costanza, A. et al. Patients with first versus multiple episodes of self-harm: how do their profiles differ?. Ann Gen Psychiatry 20, 30 (2021). https://doi.org/10.1186/s12991-021-00351-5

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/s12991-021-00351-5