Abstract

Background

Malnutrition is associated with poor prognosis in cardiovascular disease patients or in diabetic patients. However, the relationship between malnutrition and clinical outcomes in diabetic patients with coronary artery disease (CAD) is not well known. The aim of this study is to report the prevalence and prognostic consequences of malnutrition in diabetic patients with CAD.

Methods

In this retrospective observational study, the Controlling Nutritional Status (CONUT) score applied to 12,898 consecutive diabetic patients with CAD. The association between malnutrition and long-term all-cause mortality was examined using Cox proportional hazards regression analysis.

Results

According to CONUT score, 60.5% patients suffered from malnutrition; 46.4%, 13.2%, and 0.9% patients had mild, moderate, and severe malnutrition, respectively. During a median follow-up of 4.88 (2.83–7.51) years, 1973 (15.3%) patients died. After adjustment for confounders, malnutrition was associated with significantly increased risk for long-term all-cause mortality (adjusted hazard ratio for mild malnutrition and moderate to severe malnutrition, respectively: 1.38 [95% confidence interval (CI) 1.07–1.77]; P value = 0.012 and 1.63 [95% CI 1.18–2.24]; P value = 0.003). A similar association was observed around subgroups.

Conclusions

Malnutrition is common in diabetic patients with CAD and is strongly associated with increased mortality. It is necessary to adequately assess the nutritional status and take the effective nutritional guidance to improve the prognosis of diabetic patients with CAD.

Similar content being viewed by others

Background

Patients with diabetes are at high risk for cardiovascular disease (CVD) [1]. CVD, one of the major macrovascular complications, was a major cause of mortality among diabetic patients, accounting for 50.3% of all deaths. The major contributors was coronary artery disease (CAD), which was responsible for 29.7% [1]. Given the clinical burden that CVD complications have on diabetic patients, there has been an increased focus on the high-risk patients of diabetes with CVD. Identifying high-risk patients based on modifiable clinical characteristics is critical to intervening with these variables to reduce the patient's risk.

Recently, several studies show that malnutrition is correlated with increased in-hospital mortality, long-term mortality and cardiovascular events of acute coronary syndrome (ACS), acute myocardial infarction (AMI), acute heart failure (HF), chronic heart failure, and atrial fibrillation (AF) [2,3,4,5,6,7,8]. Malnutrition is also a significant and common comorbidity in diabetic patients, and it is associated with in-hospital mortality and long-term outcomes [9, 10]. Nutrition is one of the key modifiable risk factors for cardiovascular health in people with or without diabetes [11, 12]. However, the relationship between malnutrition and clinical outcomes in diabetic patients with CAD has not been reported.

Therefore, we aim to assess the prevalence and prognostic consequences of malnutrition in the high-risk patients with both diabetes and CAD using Controlling Nutritional Status (CONUT) score.

Methods

Study population

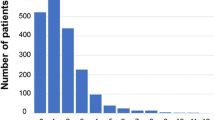

The present study was a retrospective observational cohort study, including patients who underwent coronary angiography (CAG) and were diagnosed with both diabetes mellitus (DM) and CAD according to the 10th Revision Codes of the International Classification of Diseases (ICD-10; E10–E14, I20.xx–I25.xx, I50.00001 and I91.40001) at Guangdong Provincial People’s Hospital, Guangdong, China from January 2007 to December 2018 (ClinicalTrials.gov NCT04407936). DM refers to any type of diabetes mellitus, and pregnant women were excluded. CAG or percutaneous coronary intervention (PCI) was performed following standard clinical practice guidelines [13, 14]. Patients without measurement of albumin level, total cholesterol level and lymphocyte count were excluded from this analysis (n = 1329). We also excluded patients with missing data on follow-up (n = 2040). Eventually, 12,898 patients were included (Fig. 1). The study conformed to the principles outlined in the Declaration of Helsinki and was approved by the Guangdong Provincial People’s Hospital ethics committee. All patients gave written informed consent for participation in the study.

Data collection

Data were extracted from the electronic clinical management records system of the Guangdong Provincial People’s Hospital. The baseline information mainly included demographic characteristics, medical history, medications, laboratory test results and other clinical variables. Data of long-term all-cause deaths were obtained from the Guangdong Provincial Public Security and matched to the electronic Clinical Management System of the Guangdong Provincial People’s Hospital records. Venous blood samples were collected in the early morning after overnight fasting.

Malnutrition screening tool

We choose the Controlling Nutritional Status (CONUT) score as a screening tool for malnutrition. The CONUT score was developed by Ulibarri et al. [15] in 2005 as a screening tool for the nutritional status of hospitalized patients. It automatically assesses the nutritional status by taking into account serum albumin, total cholesterol and lymphocyte count. A score of 0 to 1 reflects normal; scores of 2 to 4, 5 to 8, and 9 to 12 reflect mild, moderate, and severe malnutrition, respectively.

Endpoint and follow-up

The primary endpoint was long-term all-cause mortality. Patients were followed up since the date of admission. Follow-up data that were monitored and recorded by trained nurses and research assistants through outpatient interviews and telephones.

Statistical analysis

Continuous variables were presented as mean (standard deviation [SD]) or medians interquartile range (IQRs), and categorical variables were presented as frequency counts and percentages. One-way analysis of variance (ANOVA) was used to compare the differences in variables among groups. The chi-square test was used to compare proportions between groups.

To assess the association between malnutrition and long-term all-cause mortality, the Cox proportional hazards regression analysis was performed. Variables determining entry into the model were selected based on variables associated with known poor prognosis, clinical plausibility or P value of < 0.05 in the univariate Cox regression analyses. We also performed a subgroup analysis to assess the impact of malnutrition on long-term all-cause mortality. Time-to-event data were presented graphically using Kaplan–Meier (K–M) curves, and a log-rank test was used to assess differences between groups.

All statistical analyses were performed using R, version 4.0.3 software (R Foundation for Statistical Computing, Vienna, Austria). All P values were 2 sided, and values < 0.05 were considered significant.

Result

Patient characteristics

A total of 12,898 consecutive diabetic patients with angiographically proven CAD were enrolled. Most patients were men (70.1%), and the mean age was 63.9 ± 10.1 years. Totally, 9748 (75.6%) patients underwent PCI, and more than a quarter had multivessel CAD (26.1%; n = 3367). There were 2361 (18.3%) patients with AMI, 88(3.0%) patients with AF, 1553 (12.0%) patients with congestive heart failure(CHF), 38,825 (68.4%) patients with hypertension, 995 (7.7%) patients with stroke, 3153(24.4%) patients with chronic kidney disease (CKD), and 5066 (39.3%) patients with anemia. Glycosylated hemoglobin (HbA1c) was 7.9% ± 1.7. Fasting blood glucose (FBG) was 9.78 ± 4.62 mmol/L, and 2 h postprandial blood glucose (2hPBG) was 12.83 ± 4.41 mmol/L. Left ventricular ejection fraction (LVEF) was 58% ± 13. More data on the baseline characteristics of study population are shown in Table 2.

Prevalence and clinical associations of malnutrition

Overall, 7805 (60.5%) patients suffered from malnutrition among the 12,898 patients. By CONUT calculation, 5984 (46.4%), 1703 (13.2%), and 118 (0.9%) patients had mild, moderate, and severe malnutrition, respectively. The prevalence of malnutrition was higher in men than in women (Tables 1, 2).

According to CONUT score, 12,898 patients were divided into four groups: normal nutritional status, mild malnutrition, moderate malnutrition, and severe malnutrition. Compared with those with normal nutritional status, patients with malnutrition were older, were more likely to be men, and had worse LVEF and renal function. Their FBG level was higher, and hemoglobin (Hb) level was lower than those with normal nutritional status. They also were more likely to have multivessel CAD, AMI, AF, CHF, hypertension, stroke and anemia (Table 2). In addition, the hospital length of stay and hospitalization expenses for the malnourished patients was significantly greater than that for the normal-nourished patients (Table 3).

Malnutrition and clinical outcomes

During a median follow-up of 4.88 (2.83–7.51) years, a total of 1973 (15.3%) patients died from all causes. During hospitalization, 99 (0.8%) patients died from all causes. The in-hospital all-cause mortality was significantly increased in the malnourished patients (Table 3). Worsening malnutrition status was associated with higher incidence of all-cause mortality (Fig. 2, log-rank test, p < 0.0001).

The Cox proportional hazards regression analysis indicated that compared with normal nutritional status, malnutrition was associated with significantly increased risk for long-term all-cause mortality (adjusted hazard ratio for mild malnutrition and moderate to severe malnutrition, respectively: 1.38 [95% confidence interval (CI) 1.07–1.77]; P value = 0.012 and 1.63 [95% CI 1.18–2.24]; P value = 0.003) (Table 4).

In a subgroup analysis, the Cox regression analysis revealed that malnutrition had a relatively consistent risk of mortality across dichotomized subgroups (gender, old, CKD, CHF, AF, AMI, and anemia). Significant interaction (P-interaction = 0.02) between malnutrition and hypertension was observed (Fig. 3).

Discussion

To our knowledge, this is the first study to explore the prevalence and mortality of malnutrition in the high-risk population with both diabetes and angiographically proven CAD. In the study, we found that malnutrition evaluated by CONUT score was common in diabetic patients with CAD. The in-hospital mortality, hospital length of stay, and hospitalization expenses for the malnourished patients was significantly greater than that for the normal-nourished patients. Our research also showed that malnutrition was associated with a poor prognosis regardless of age, HbA1c, AF, CHF, CKD, anemia, and other risk factors. In addition, similar results were found among different subgroups.

Malnutrition was a very common problem in hospitalized elder patients with different diseases [16, 17]. 21% hospitalized elderly patients with diabetes suffered from malnutrition [10]. Roubín SR, et al. reported that the percentage of ACS patients with malnutrition varied from 8.9% with the Prognostic Nutritional Index (PNI), to 49.8% with the CONUT score, and to 59.5% with the Nutritional Risk Index (NRI). The CONUT score showed the highest predictive ability, whereas the NRI had the lowest [3]. Therefore, we chose CONUT score to evaluate nutritional status and found that 60.5% patients with both CAD and diabetes suffered from malnutrition. Hospital malnutrition was associated with an increase in mortality, a higher readmission rate, need of rehabilitation support after discharge and higher healthcare [18,19,20]. In concordance with the above research, our study indicated that the hospitalization expenses for the malnourished patients was significantly greater than that for the normal-nourished patients. In addition, we reported the in-hospital all-cause mortality and hospital length of stay were significantly increased in the malnourished patients.

There was evidence to indicate worsening of clinical outcomes when diabetes was associated with poor nutritional status, especially in geriatric patients [21]. The risk for mortality in elderly patients with diabetes increased by 69% in malnourished versus normal-nourished patients [9]. Among ACS patients, mild malnutrition increased 36% risk for long-term all-cause mortality, while moderate increased 1.02-fold and severe increased 2.65-fold, respectively than normal nutritional status [3]. Compared with the study in ACS patients, slightly higher risk for mortality was found in the mild malnutrition in our study, but the risk in the moderate to severe malnutrition was lower than in the ACS patients. The reason might be the severity of CAD was lower than the above research due to the proportion of AMI in our study was just 18.3%. Our research showed that the risk for mortality in the moderate to severe malnutrition was slightly lower than the risk in the elderly diabetic patients. This result may be explained in part by different ways of assessing malnutrition and different disease spectrum and age composition of patients. In short, our study found that the more severe the malnutrition, the higher the long-term all-cause mortality, and moderate to severe malnutrition could cause worse prognosis than mild malnutrition. The admission nutritional status was an independent predictor of long-term mortality in diabetic patients with CAD.

Why does malnutrition coexist with DM and CAD in hospitalized patients? This may be related to the effect of the acute disease that led to hospitalization. How does nutritional status influence the prognosis of diabetic patients with CAD remains unclear. One possible explanation is that nutritional status may be a proxy indicator of inflammation [22]. Chronic inflammatory diseases correlate with increased production of catabolic cytokines, muscle catabolism, and appetite suppression and, thereby, lower albumin level [23]. Diabetes is associated with increased systemic inflammation. Furthermore, inflammation is recognized in the pathogenesis of atherosclerotic CVD events [24, 25]. Our study found that the more severe the malnutrition, the higher the hypersensitive C reactive protein level. High degree of malnutrition is associated with high level of inflammation, which translates into increased atherosclerotic burden. The relationship between these 3 entities has recently been described as malnutrition-inflammation-atherosclerosis syndrome [26].

Despite the growing body of studies demonstrating the risk of malnutrition, malnutrition is not commonly listed as a comorbidity of DM and CAD. Our findings strongly support the need for physicians to practice early identification of malnutrition in the high-risk population. Since the variables required for CONUT score calculation are widely available from routine clinical examination, malnutrition might be systematically screened in the DM and CAD setting. Screening these patients might identify patients at high risk of poor outcomes who might benefit from tailored secondary prevention programs with nutritional supplements to improve their prognosis. The interventions should be started during the hospitalization such as nutrition consultation from a dietitian and also continue after discharge to ensure normalization of nutritional status. The present studies demonstrate that mediterranean dietary regimens has a beneficial role in reducing the risk of the incidence and mortality of CVD in population inclusive of individuals with diabetes [12, 27]. Clinicians should keep abreast of current scientific evidence to provide these high-risk patients with effective nutrition guidance. Furthermore, some measures to address chronic inflammation should also be explored.

Limitation

First, our results were subject to limitations of the observational nature inherent in the retrospectively collected database. Second, we did not compare the prognostic value of nutritional screening tools with more complex comprehensive nutritional screening tools, and we did not investigate the changes in nutritional status over time and their association with outcomes. Third, long-term all-cause mortality was complex and multivariable. Due to the lack of other endpoint events, this will limit to generalize our results. Finally, we did not evaluate the relationship of malnutrition scores with inflammatory markers or with body mass index (BMI) because of the lack of height and weight in our database.

Conclusion

The prevalence of malnutrition in diabetic patients with CAD was very high. Worsening malnutrition was associated with increased risk of all-cause mortality. Malnutrition assessment could allow clinicians to identify diabetic patients with CAD at elevated risk for mortality. Adequate assessment of nutritional status and necessary nutrition guidance can help improve the prognosis of diabetic patients with CAD.

Availability of data and materials

Not applicable.

Abbreviations

- ACS:

-

Acute coronary syndrome

- AMI:

-

Acute myocardial infarction

- AF:

-

Atrial fibrillation

- ACEI/ARB:

-

Angiotensin-converting enzyme inhibitor/angiotensin receptor blocker

- CONUT:

-

Controlling Nutritional Status

- CVD:

-

Cardiovascular disease

- CAD:

-

Coronary artery disease

- CHF:

-

Congestive heart failure

- CKD:

-

Chronic kidney disease

- CREA:

-

Creatinine

- CCB:

-

Calcium channel blocker

- DM:

-

Diabetes mellitus

- eGFR:

-

Estimated glomerular filtration rate

- FBG:

-

Fasting blood glucose

- HF:

-

Heart failure

- Hb:

-

Hemoglobin

- HbA1c:

-

Glycosylated hemoglobin

- HDL-C:

-

High density lipoprotein cholesterol

- hs-CRP:

-

Hypersensitive C-reactive protein

- LDL-C:

-

Low density lipoprotein cholesterol

- LVEF:

-

Left ventricular ejection fraction

- NRI:

-

Nutritional Risk Index

- OADs:

-

Oral antidiabetic drugs

- PCI:

-

Percutaneous coronary intervention

- PNI:

-

Prognostic Nutritional Index

- TC:

-

Total cholesterol

- TG:

-

Triglycerides

- T2DM:

-

Type 2 diabetes mellitus

- T1DM:

-

Type 1 diabetes mellitus

- 2hPBG:

-

2 Hours postprandial blood glucose

References

Einarson TR, Acs A, Ludwig C, Panton UH. Prevalence of cardiovascular disease in type 2 diabetes: a systematic literature review of scientific evidence from across the world in 2007–2017. Cardiovasc Diabetol. 2018;17(1):83.

Czapla M, Karniej P, Juarez-Vela R, Lokiec K. The association between nutritional status and in-hospital mortality among patients with acute coronary syndrome: a result of the retrospective nutritional status heart study (NSHS). Nutrients. 2020;12(10):3091.

Raposeiras Roubin S, Abu Assi E, Cespon Fernandez M, Barreiro Pardal C, Lizancos Castro A, Parada JA, Perez DD, Blanco Prieto S, Rossello X, Ibanez B, et al. Prevalence and prognostic significance of malnutrition in patients with acute coronary syndrome. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2020;76(7):828–40.

Tonet E, Campo G, Maietti E, Formiga F, Martinez-Selles M, Pavasini R, Biscaglia S, Serenelli M, Sanchis J, Diez-Villanueva P, et al. Nutritional status and all-cause mortality in older adults with acute coronary syndrome. Clin Nutr (Edinburgh, Scotland). 2020;39(5):1572–9.

Yoo SH, Kook HY, Hong YJ, Kim JH, Ahn Y, Jeong MH. Influence of undernutrition at admission on clinical outcomes in patients with acute myocardial infarction. J Cardiol. 2017;69(3):555–60.

Sze S, Pellicori P, Kazmi S, Rigby A, Cleland JGF, Wong K, Clark AL. Prevalence and prognostic significance of malnutrition using 3 scoring systems among outpatients with heart failure: a comparison with body mass index. JACC Heart Fail. 2018;6(6):476–86.

Raposeiras-Roubin S, Abu-Assi E, Paz RC, Rossello X, Barreiro Pardal C, Pinon Esteban M, Pascual CR, Garcia Comesana J, Gonzalez-Carrero Lopez A, Caneiro-Queija B, et al. Impact of malnutrition in the embolic–haemorrhagic trade-off of elderly patients with atrial fibrillation. Europace. 2020;22(6):878–87.

Czapla M, Juarez-Vela R, Lokiec K, Karniej P. The association between nutritional status and in-hospital mortality among patients with heart failure: a result of the retrospective nutritional status heart study 2 (NSHS2). Nutrients. 2021;13(5):1669.

Ahmed N, Choe Y, Mustad VA, Chakraborty S, Goates S, Luo M, Mechanick JI. Impact of malnutrition on survival and healthcare utilization in Medicare beneficiaries with diabetes: a retrospective cohort analysis. BMJ Open Diabetes Res Care. 2018;6(1):e000471.

Sanz Paris A, Garcia JM, Gomez-Candela C, Burgos R, Martin A, Matia P. Study Vg: malnutrition prevalence in hospitalized elderly diabetic patients. Nutr Hosp. 2013;28(3):592–9.

Freeman AM, Morris PB, Barnard N, Esselstyn CB, Ros E, Agatston A, Devries S, O’Keefe J, Miller M, Ornish D, et al. Trending cardiovascular nutrition controversies. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2017;69(9):1172–87.

Becerra-Tomas N, Blanco Mejia S, Viguiliouk E, Khan T, Kendall CWC, Kahleova H, Rahelic D, Sievenpiper JL, Salas-Salvado J. Mediterranean diet, cardiovascular disease and mortality in diabetes: a systematic review and meta-analysis of prospective cohort studies and randomized clinical trials. Crit Rev Food Sci Nutr. 2020;60(7):1207–27.

Writing Committee M, Jneid H, Anderson JL, Wright RS, Adams CD, Bridges CR, Casey DE Jr, Ettinger SM, Fesmire FM, Ganiats TG, et al. 2012 ACCF/AHA focused update of the guideline for the management of patients with unstable angina/Non-ST-elevation myocardial infarction (updating the 2007 guideline and replacing the 2011 focused update): a report of the American College of Cardiology Foundation/American Heart Association Task Force on practice guidelines. Circulation. 2012;126(7):875–910.

Levine GN, Bates ER, Blankenship JC, Bailey SR, Bittl JA, Cercek B, Chambers CE, Ellis SG, Guyton RA, Hollenberg SM, et al. 2015 ACC/AHA/SCAI focused update on primary percutaneous coronary intervention for patients with ST-elevation myocardial infarction: an update of the 2011 ACCF/AHA/SCAI guideline for percutaneous coronary intervention and the 2013 ACCF/AHA guideline for the management of ST-elevation myocardial infarction. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2016;67(10):1235–50.

Ignacio de Ulibarri J, Gonzalez-Madrono A, de Villar NG, Gonzalez P, Gonzalez B, Mancha A, Rodriguez F, Fernandez G. CONUT: a tool for controlling nutritional status. First validation in a hospital population. Nutr Hosp. 2005;20(1):38–45.

Gomez Ramos MJ, Gonzalez Valverde FM, Sanchez Alvarez C. Nutritional status of an hospitalised aged population. Nutr Hosp. 2005;20(4):286–92.

Malafarina V, Reginster JY, Cabrerizo S, Bruyere O, Kanis JA, Martinez JA, Zulet MA. Nutritional status and nutritional treatment are related to outcomes and mortality in older adults with hip fracture. Nutrients. 2018;10(5):555.

Alvarez-Hernandez J, PlanasVila M, Leon-Sanz M, GarciadeLorenzo A, Celaya-Perez S, Garcia-Lorda P, Araujo K, Sarto GB, Researchers PR. Prevalence and costs of malnutrition in hospitalized patients; the PREDyCES Study. Nutr Hosp. 2012;27(4):1049–59.

Willis H. Causes, assessment and treatment of malnutrition in older people. Nurs Older People. 2017;29(2):20–5.

Lim SL, Ong KC, Chan YH, Loke WC, Ferguson M, Daniels L. Malnutrition and its impact on cost of hospitalization, length of stay, readmission and 3-year mortality. Clin Nutr (Edinburgh, Scotland). 2012;31(3):345–50.

Vischer UM, Perrenoud L, Genet C, Ardigo S, Registe-Rameau Y, Herrmann FR. The high prevalence of malnutrition in elderly diabetic patients: implications for anti-diabetic drug treatments. Diabetic Med J Br Diabetic Assoc. 2010;27(8):918–24.

Kalantar-Zadeh K, Anker SD, Horwich TB, Fonarow GC. Nutritional and anti-inflammatory interventions in chronic heart failure. Am J Cardiol. 2008;101(11A):89E-103E.

Merker M, Felder M, Gueissaz L, Bolliger R, Tribolet P, Kagi-Braun N, Gomes F, Hoess C, Pavlicek V, Bilz S, et al. Association of baseline inflammation with effectiveness of nutritional support among patients with disease-related malnutrition: a secondary analysis of a randomized clinical trial. JAMA Netw Open. 2020;3(3):e200663.

Patel KV, Vaduganathan M. Targeting multiple domains of residual cardiovascular disease risk in patients with diabetes. Curr Opin Cardiol. 2020;35(5):517–23.

Bray JJH, Foster-Davies H, Stephens JW. A systematic review examining the effects of sodium-glucose cotransporter-2 inhibitors (SGLT2is) on biomarkers of inflammation and oxidative stress. Diabetes Res Clin Pract. 2020;168:108368.

Sueta D, Hokimoto S, Sakamoto K, Akasaka T, Tabata N, Kaikita K, Honda O, Naruse M, Ogawa H. Multi-center study of hemodialysis patients undergoing invasive cardiovascular procedures study I: validation of the high mortality rate of malnutrition-inflammation-atherosclerosis syndrome: community-based observational study. Int J Cardiol. 2017;230:97–102.

Mosharraf S, Sharifzadeh G, Darvishzadeh-Boroujeni P, Rouhi-Boroujeni H. Impact of the components of Mediterranean nutrition regimen on long-term prognosis of diabetic patients with coronary artery disease. ARYA Atheroscler. 2013;9(6):337–42.

Acknowledgements

We are very grateful to all the staff for helping with the present study. We are grateful to all participants for their dedication to data collection.

Funding

This research was funded and supported by Guangdong Provincial Science and Technology Plan Project (2017B030314041); Guangdong Provincial Fund for Clinical Medications (2019ZH01); Multi-center study on key techniques for prevention, diagnosis and treatment of high risk coronary artery disease (DFJH2020026); Study on the function and mechanism of the potential target for early warning of cardiorenal syndrome after acute myocardial infarction based on transmoomics (DFJH201919); Natural Science Foundation of Guangdong Province General Project (2020A1515010940).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Substantial contributions to the conception and design of the study (SQC, HC, MT); data collection (ZHW,JRL,YRY, HZH, QL, BW); data analysis and/or interpretation of data for the work (YYW, LYZ, GDL, ZDH,YHZ); drafting of the work or revising it critically for important intellectual content (WW,JL,YL); final approval of the version to be published (all the authors).

Corresponding authors

Ethics declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate

The study was approved by the Research Ethics Committee of Guangdong Provincial People’s Hospital, Guangdong Academy of Medical Sciences. All participants provided written informed consent prior to enrolment.

Consent for publication

All authors support the submission to this journal.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/. The Creative Commons Public Domain Dedication waiver (http://creativecommons.org/publicdomain/zero/1.0/) applies to the data made available in this article, unless otherwise stated in a credit line to the data.

About this article

Cite this article

Wei, W., Zhang, L., Li, G. et al. Prevalence and prognostic significance of malnutrition in diabetic patients with coronary artery disease: a cohort study. Nutr Metab (Lond) 18, 102 (2021). https://doi.org/10.1186/s12986-021-00626-4

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/s12986-021-00626-4