Abstract

Background

The development of the polymerase chain reaction (PCR) test promoted the evaluation of the epidemiological and clinical characteristics of human parainfluenza virus (HPIV) type 4, which has been rarely studied using conventional diagnostic methods. This study aimed to determine the seasonal epidemiological and clinical characteristics of all four HPIV serotypes (HPIV-1, HPIV-2, HPIV-3, and HPIV-4) during the era of PCR testing.

Methods

The medical records of hospitalized pediatric patients diagnosed with HPIV infections by a multiplex PCR test between 2015 and 2021 were retrospectively reviewed to determine the seasonal distributions of each HPIV serotype. For patients with a single HPIV infection, the clinical characteristics of each HPIV serotype were evaluated and compared with one another.

Results

Among the 514 cases of HPIV infection, HPIV-1, HPIV-2, HPIV-3, and HPIV-4 were identified in 27.2%, 11.9%, 42.6%, and 18.3% of cases, respectively. HPIV-3 was most prevalent in spring, and the other three serotypes were most prevalent in autumn. For patients with a single HPIV infection, those infected by HPIV-1 and HPIV-3 were younger than those infected by HPIV-2 and HPIV-4 (P < 0.001). Croup and lower respiratory tract infection (LRI) were most frequently diagnosed in patients infected by HPIV-1 (P < 0.001) and HPIV-4 (P = 0.002), respectively. During 2020–2021, HPIV-3 was most prevalent in autumn and caused fewer LRIs (P = 0.009) and more seizures (P < 0.001) than during 2015–2019.

Conclusions

Each HPIV serotype exhibited a distinct seasonal predominance, and some differences in the clinical characteristics of the HPIV serotypes were observed. HPIV-4 acted as an important cause of LRI. Considering the recent changes in the epidemiological and clinical characteristics of HPIV-3, more time-series analyses should be conducted.

Similar content being viewed by others

Background

Human parainfluenza virus (HPIV) is one of the major viral causes of upper respiratory tract infection (URI) and lower respiratory tract infection (LRI) in children, accounting for about 10% of hospitalized children with respiratory tract infections [1, 2]. Also, HPIV is the most common cause of croup, accounting for 38–64% of cases [1,2,3]. HPIV is an enveloped single-strand, negative-sense RNA virus that belongs to the Paramyxoviridae family [4]. HPIV is divided into four genetically and antigenically distinct serotypes (HPIV-1, HPIV-2, HPIV-3, and HPIV-4), and there are two genera of HPIV: Respirovirus (HPIV-1 and HPIV-3) and Rubulovirus (HPIV-2 and HPIV-4) [4]. Moreover, there are genetically distinct strains in each serotype: three genetic clusters each in HPIV-1 and HPIV-3 and four genetic clusters each in HPIV-2 and HPIV-4 have been reported [4,5,6,7]. Because genetic information about HPIV is still insufficient, studies of genetic variation based on the whole genome or hemagglutinin-neuraminidase (HN) gene in each HPIV serotype have been conducted [5,6,7]. Each HPIV serotype exhibits different epidemiological patterns. Among the four serotypes, infection with HPIV-3 exhibits the highest prevalence, and it peaks in spring and summer [1, 3, 8,9,10,11]. Epidemics of HPIV-1 and HPIV-2 infections generally occur in biennial autumn [1, 3, 8,9,10,11]. Because of difficulties in isolating the virus, HPIV-4 has rarely been tested using antigen detection tests and cell cultures [4], and resultantly, the seasonality and clinical characteristics of HPIV-4 infection are less defined than those of the other serotypes. The epidemiological and clinical characteristics corresponding to the genetic variations of each HPIV serotype have been poorly studied even for HPIV-3 [12]. With an improved diagnostic sensitivity for HPIV-4 after the introduction of molecular diagnostic tests, such as the polymerase chain reaction (PCR) test [13], various multiplex PCR tests simultaneously identifying the four HPIV serotypes have been recently used in a real-life clinical setting [4]. Although reports on the epidemiological and clinical characteristics of HPIV-4 infection are increasing from the use of PCR tests, various and inconsistent results were reported because of differences in the study design, study duration, geographic area, patient number, and subject selection criteria (e.g., age, diagnosis, and hospitalization status) between the studies [14,15,16,17,18,19]. Therefore, more studies including various study populations and study years should be performed in each geographic area. In this study, the epidemiological and clinical characteristics of HPIV infection during a 7-year period were determined and compared among the four HPIV serotypes in Korean pediatric patients.

Methods

Subjects and study design

Pediatric patients (< 19 years of age) admitted to the Department of Pediatrics at Daejeon St. Mary’s Hospital (Daejeon, Republic of Korea) between January 2015 and December 2021 and underwent evaluations for respiratory viruses using a multiplex PCR test were recruited for this study. Among them, the patients who were positive for HPIV infections were included in this study. Patients who were positive for two or more HPIV serotypes simultaneously were excluded from the study analysis because they could have combined clinical manifestations of the different serotypes. If the same HPIV serotype was identified within 4 weeks after a previous HPIV infection, that episode was excluded, considering prolonged shedding of HPIV unrelated to current symptoms. The electronic medical records of the included patients were retrospectively reviewed to collect the demographic data, including sex and age; clinical data, including the presenting symptoms, diagnosis on discharge, breath sounds, and severe complications (receiving oxygen therapy or intensive care); laboratory data, including the complete blood count, erythrocyte sedimentation rate, and C-reactive protein, aspartate transaminase, alanine transaminase, and lactate dehydrogenase levels; and chest x-ray findings. For the diagnosis on discharge, URI was diagnosed when the patient complained of any respiratory symptoms without abnormal breath sounds and chest x-ray findings. Croup was diagnosed when the patient presented with barking cough and hoarseness with or without stridor. LRI was diagnosed when the patient complained of any respiratory symptoms, which were accompanied by abnormal breath sounds or abnormal chest x-ray findings. Among the LRIs, pneumonia was diagnosed when the chest x-ray abnormality was segmental or lobar consolidation; otherwise, bronchitis/bronchiolitis was diagnosed. If a patient experienced LRI following croup, each episode of croup and LRI was assigned separately. Febrile patients without any respiratory symptoms, abnormal physical examination, and abnormal chest x-ray findings were diagnosed with fever without localizing signs (FWLS). The month, season, and year of the diagnosis of HPIV infection were investigated. Because Korea is located in a northern temperate area, four seasons were defined as follows: spring, March to May; summer, June to August; autumn, September to November; and winter, December to February. The included patients were divided into four groups according to the identified HPIV serotype: the HPIV-1, HPIV-2, HPIV-3, and HPIV-4 groups. For the entire study population, including the patients with a single HPIV infection and those with a co-infection of HPIV and other respiratory viruses, the monthly and seasonal distributions of each HPIV serotype were determined. The clinical characteristics of HPIV infection were determined and compared among the four patient groups in patients with a single HPIV infection only, considering confounding effects of other co-identified viruses. The present study protocol was reviewed and approved by the Institutional Review Board of Daejeon St. Mary’s Hospital, which waived the need for informed consent (approval No. DC22RASI0020).

Microbiological analysis

Multiplex PCR tests for respiratory viruses were performed on nasopharyngeal swabs using a commercially available Allplex Respiratory Panel 1/2/3 kit (Seegene Inc., Seoul, Republic of Korea). The Allplex Respiratory Panel 1/2/3 kit is a one-step real-time RT-PCR assay based on multiple detection temperature technology [20], and simultaneously identifies 16 respiratory viruses in a single fluorescence channel without melting curve analysis: HPIV (types 1–4), adenovirus, bocavirus, coronavirus (229E, NL63, and OC43), enterovirus, human metapneumovirus, influenza A and B viruses with subtyping, respiratory syncytial virus (RSV; groups A and B), and rhinovirus. Nucleic acid extraction was performed using a GeneAll® Viral DNA/RNA Extraction kit (GeneAll Biotechnology Co., Seoul, Republic of Korea) according to the manufacturer`s instruction. Real-time RT-PCR was performed using a CFX96 real-time PCR detection system (Bio-Rad, Hercules, CA, USA). Automated analysis of the results was performed using a Seegene Viewer software (Seegene Inc.). Samples were considered positive when the cycle threshold was < 42.

Statistical analysis

Categorical data were compared using a chi-square test between the patient groups, and continuous data were compared using the Mann–Whitney test (between two groups) or Kruskal–Wallis test (between four groups). The proportions of each serotype according to the month and season were compared using the chi-square test. The SPSS 21 software program (IBM Corporation, Armonk, NY, USA) was used to perform all of the statistical analyses. The threshold of statistical significance was defined as a P-value of 0.05.

Results

Between January 2015 and December 2021, a total of 4517 multiplex PCR tests were performed in pediatric inpatients, and 3298 (73.0%) of them were positive for at least one respiratory virus. HPIV was identified in 521 (11.5%) multiplex PCR tests, and four episodes in which two HPIV serotypes were identified concurrently were excluded. Three patients were repeatedly positive for the same HPIV serotype within 4 weeks after a previous infection. They had concurrent rhinovirus or bocavirus infection on the second test, and their second episodes of HPIV infection were excluded. For the remaining 514 episodes of HPIV infection (302 [58.8%] males and 212 [41.2%] females), the median age of the included patients were 22 months (interquartile range 13–36), and 384 (74.7%) of them were aged < 36 months. HPIV was co-identified with other respiratory viruses in 324 (63.0%) episodes and identified singly in 190 (37.0%) episodes. HPIV-1, HPIV-2, HPIV-3, and HPIV-4 infections were identified in 140 (27.2%), 61 (11.9%), 219 (42.6%), and 94 (18.3%) episodes, respectively. The co-identification rates of HPIV-1, HPIV-2, HPIV-3, and HPIV-4 with other viruses were 65.0% (n = 91), 70.5% (n = 43), 61.6% (n = 135), and 58.5% (n = 55), respectively (P = 0.441).

Epidemiology of HPIV infection by serotype

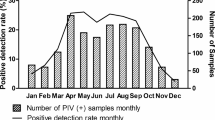

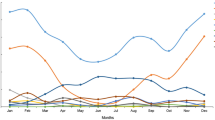

The monthly and seasonal distributions of each HPIV serotype were determined for the 514 episodes of HPIV infection (Fig. 1). Because of the pandemic of coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19), only 3 and 26 episodes were identified in 2020 and 2021, respectively. Before the COVID-19 pandemic in 2015–2019, HPIV-3 was the most prevalent of four serotypes every year, with annual peaks between April and June (Fig. 1A). HPIV-1 showed a less-prominent seasonal peak than HPIV-3, and HPIV-2 and HPIV-4 showed various seasonal patterns in each year (Fig. 1A). However, over the study period, HPIV-1, HPIV-2, and HPIV-4 showed seasonal peaks in autumn (Fig. 1B). During the COVID-19 pandemic in 2021, HPIV-3 showed a seasonal peak in autumn, which was different from previous epidemical patterns for this serotype (Fig. 1A).

Clinical characteristics of HPIV infection by serotype

The clinical characteristics of HPIV infection were evaluated in 190 patients with a single HPIV infection, and they were compared among the HPIV-1, HPIV-2, HPIV-3, and HPIV-4 groups (Table 1). The patients in the HPIV-1 and HPIV-3 groups were younger than those in the HPIV-2 and HPIV-4 groups (P < 0.001). Most patients in the HPIV-1 and HPIV-3 groups were aged < 36 months, while about half of the patients in the HPIV-2 and HPIV-4 groups were aged ≥ 36 months (Table 1). Fever developed least frequently (P < 0.001) and fever duration was shortest (P = 0.005) in the HPIV-4 group (Table 1), whereas, sputum was accompanied by HPIV infection most frequently in the HPIV-4 group (P = 0.001, Table 1). Each virus type caused a range of illnesses, from FWLS to pneumonia (Table 1). Croup was diagnosed most frequently in the HPIV-1 group (P < 0.001), while none in the HPIV-4 group were diagnosed with croup (Table 1). About half of the patients in the HPIV-2 and HPIV-3 groups were diagnosed with URI, whereas ≥ 70% of the patients in the HPIV-1 and HPIV-4 groups were diagnosed with croup or LRI (Table 1). LRI developed most frequently in the HPIV-4 group (p = 0.002). Accordingly, abnormal breath sounds and chest x-ray abnormalities were more frequent in the HPIV-1 and HPIV-4 groups than in the HPIV-2 and HPIV-3 groups (P = 0.004, Table 1). However, severe complications were rare, and their frequencies were comparable among the four groups. There were no significant differences in the laboratory test results among the four groups.

During the COVID-19 pandemic in 2020–2021, 12 (80.0%) of 15 single HPIV infections were caused by HPIV-3. Significantly more patients in the HPIV-3 group were diagnosed with URI during the COVID-19 pandemic than before the COVID-19 pandemic (83.3% vs. 38.9%, P = 0.004, Table 2). Therefore, the frequencies of abnormal breath sounds (P = 0.048) and chest x-ray abnormalities (P = 0.007) decreased significantly during the COVID-19 pandemic compared with before the pandemic (Table 2). In addition, more patients experienced seizures during the COVID-19 pandemic than before the COVID-19 pandemic (50.0% vs. 2.8%, P < 0.001, Table 2).

Discussion

The seasonal distributions and clinical characteristics of HPIV infection were determined by serotype in this study. HPIV-3 showed a peak in spring, while the other three serotypes showed peaks in autumn. There were some differences in the clinical characteristics among the four HPIV serotypes and over time.

In this study, it was reaffirmed that HPIV infection occurred mostly in young children, with a peak between spring and autumn, and caused a range of respiratory tract infections [1, 3, 8, 10]. HPIV-3 was the most prevalent among the four serotypes, consistent to the previously reported results [10, 11, 15, 17,18,19], and similar seasonal trends and clinical characteristics of HPIV-3 infection to those previously reported were identified: HPIV-3 was prevalent in spring and summer annually [1, 3, 8,9,10,11, 15, 17,18,19], patients infected by HPIV-3 tended to be younger than those infected by other serotypes [1, 3, 9, 18], and croup was diagnosed infrequently [3, 8, 9, 16,17,18]. Therefore, we can regard HPIV infections in spring and summer as non-specific URI or LRI rather than croup, caused by HPIV-3 in young children and infants.

Serotypes other than HPIV-3 showed different seasonality. Most previous epidemiological studies showed biennial epidemics of HPIV-1 and HPIV-2 in autumn [1, 3, 10, 11]. In this study, HPIV-1 was epidemic in annual autumn in 2015–2017, consistent with previously reported results in Korean children in 2013–2017 [17, 18]. Whereas, HPIV-1 infection was widespread from spring to autumn in 2018 and 2019, which was consistent with a Chinese study showing fluctuations without distinct seasonality of HPIV-1 [15, 21]. The seasonality of HPIV-2 was more varied than that of HPIV-1: epidemics in biennial autumn, annual autumn, and annual winter were reported [1, 3, 9,10,11, 17, 18, 22], and some studies failed to find a distinct seasonality of HPIV-2 [8, 15, 16, 19, 21]. In this study, HPIV-2 was prevalent in autumn as a whole; however, a regular seasonality could not be defined due to the lowest number of HPIV-2 identification among the four serotypes, clustered in 2015 and 2019. HPIV-4 was not tested or was identified least frequently among the four serotypes before the introduction of PCR tests [3, 8, 9, 22], and therefore, information on its seasonality and clinical characteristics was insufficient. With the use of PCR tests, HPIV-4 infection has been identified more frequently than HPIV-2 infection [15,16,17,18, 21], and therefore, its clinical significance was required to be determined. In this study, HPIV-4 was prevalent in autumn as a whole; however, it was prevalent in spring in 2017 and the numbers of identification varied year to year. Nationwide studies for several years in the UK and USA reported annual epidemics of HPIV-4 in autumn [10, 11], while Korean and Chinese studies with ≤ 5 years of study period reported fluctuating seasonal patterns of HPIV-4 [15, 17,18,19, 21]. As a result, the seasonality of HPIV types 1, 2, and 4 varied according to geographic area, study duration, patient number, and identification method in previous reports and this study. Moreover, seasonal epidemiology tended to be different over time even in a same country. Although HPIV-3 was most prevalent with an annual epidemic in spring consistently in temperate areas, HPIV-3 did not exhibit a distinct seasonality or other serotypes were more predominant than HPIV-3 in tropical and subtropical areas [23, 24]: a climate factor cannot be ignored. Therefore, seasonal epidemiology of HPIV infections should be determined in each country independently by observing for sufficient years, and its changing trends should be traced.

Considering that HPIV-2 infections were least frequent among serotypes prevalent in autumn and less than a quarter of them manifested as LRI, clinical differentiation between HPIV-1 and HPIV-4 infections might be emphasized in patients infected by HPIV in autumn. Except that more patients in the HPIV-1 group were aged < 36 months, febrile, and diagnosed with croup than those in the HPIV-4 group, similar clinical, radiological, and laboratory findings and outcomes were identified between HPIV-1 and HPIV-4 groups in this study. Therefore, clinical differentiation between HPIV-1 and HPIV-4 infections seems to have little clinical impact. We can only consider that LRIs in young children and most cases of croup are caused by HPIV-1, and LRIs in old children are caused by HPIV-4 in autumn.

During the COVID-19 pandemic, respiratory and gastrointestinal infectious diseases decreased with intensive infection control and prevention strategies in Korea [25]. Accordingly, the numbers of HPIV identified in 2020–2021 were significantly lower than those in 2015–2019. Moreover, different seasonality and clinical manifestations of HPIV infections from those before the COVID-19 pandemic were observed in 2021: HPIV-3 was prevalent in autumn, not in spring, significantly more patients were diagnosed with URI and experienced seizures in the HPIV-3 group than before. Before the COVID-19 pandemic, seizures occurred in 2.8% of the HPIV-3 group and were accompanied by HPIV-2 infection most frequently (11.1%). Previously, HPIV was identified in about 10% of children with febrile seizures [1, 26], and 9–16% of pediatric patients with HPIV infections experienced seizures [1, 27]. Due to the small number of patients during the COVID-19 pandemic, we could not evaluate why the seasonality and clinical characteristics of HPIV infection changed. A new genetic lineage of HPIV-3 circulated in Korea in 2021 was identified, and multiple HN gene mutations were found by genetic analysis of the HN gene [28]. However, the clinical significance of these genetic variations could not be defined [28]. The resurgence of HPIV infection in 2021 was also observed in China and Japan, neighboring countries of Korea, and in western countries with the relaxation of social knockdown [29,30,31,32,33,34]. Because immunity to HPIV infection is transient and wanes over time [4], the absence of re-infections in the community during social knockdown could increase the population susceptible to HPIV infection [34]. Considering that HPIV-3 tends to infect younger children than other HPIV serotypes, the exemption of mask use for children aged < 24 months could be associated with the resurgence of HPIV-3 infection, as was observed with the resurgence of RSV infection in 2021 in several countries including Korea [30]. Moreover, the mass migration of the population during the Korean Thanksgiving in late September might increase the transmission of HPIV in the community in Korea. Further follow-up studies should be conducted after the cessation of the COVID-19 pandemic to trace the trends of seasonal epidemiology and clinical characteristics of HPIV infections.

This study had some limitations including a selection bias due to its retrospective nature. Especially, this study included inpatients only, and therefore, outpatients with mild symptoms were not included and disease severity might be overestimated. Previous studies including outpatients reported the frequency of LRI as < 10% [3, 8]. However, a similar seasonality of HPIV between a community surveillance cohort and hospitalized patients was reported [35]. Despite seven years of study duration, a small number of patients were included during the last two years due to the COVID-19 pandemic in this study. Considering geographic and climate factors on the seasonality of HPIV, the results of this study might not be applicable to other countries; however, they are worth to note in temperate countries. Genetic analyses for HPIV were not performed in this study. Compared with RSV, which belongs to the Paramyxoviridae family, information on genetic variants and molecular epidemiology is more limited for HPIV. Further multinational studies including many patients over several years are needed to define the genotypes of HPIV and to evaluate the epidemiological and clinical characteristics of each HPIV genotype.

Conclusions

In conclusion, in Korea with a temperate climate, HPIV-3 was prevalent in spring, and the other serotypes were prevalent in autumn. Although the differences of clinical characteristics among three prevalent serotypes in autumn seemed to have insignificant impact, HPIV-4 acted as a significant lower respiratory pathogen. The seasonality of HPIV varied according to geographic area, climate, study duration, patient characteristics, and laboratory test method, and the COVID-19 pandemic might influence the seasonality and clinical manifestations of HPIV infections. Follow-up studies including pre- and post-COVID-19 periods of sufficient years should be performed independently in each geographic area.

Availability of data and materials

The datasets used and analyzed during the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

Abbreviations

- COVID-19::

-

Coronavirus disease 2019

- FWLS::

-

Fever without localizing signs

- HN: :

-

Hemagglutinin-neuraminidase

- HPIV::

-

Human parainfluenza virus

- LRI::

-

Lower respiratory tract infection

- PCR::

-

Polymerase chain reaction

- RSV::

-

Respiratory syncytial virus

- URI::

-

Upper respiratory tract infection

References

Downham MA, McQuillin J, Gardner PS. Diagnosis and clinical significance of parainfluenza virus infections in children. Arch Dis Child. 1974;49:8–15.

Choi E, Ha KS, Song DJ, Lee JH, Lee KC. Clinical and laboratory profiles of hospitalized children with acute respiratory virus infection. Korean J Pediatr. 2018;61:180–6.

Reed G, Jewett PH, Thompson J, Tollefson S, Wright PF. Epidemiology and clinical impact of parainfluenza virus infections in otherwise healthy infants and young children < 5 years old. J Infect Dis. 2003;175:807–13.

Henrickson KJ. Parainfluenza viruses. Clin Microbiol Rev. 2003;16:242–64.

Almajhdi FN, Alshaman MS, Amer HM. Human parainfluenza virus type 2 hemagglutinin-neuramindase gene: sequence and phylogenetic analysis of the Saudi strain Riyadh 105/2009. Virol J. 2012;9:316.

Bose ME, Shrivastava S, He J, Nelson MI, Bera J, Fedorova N, et al. Sequencing and analysis of globally obtained human parainfluenza viruses 1 and 3 genomes. PLoS ONE. 2019;14: e0220057.

Zou S, Mao N, Zhang Y, Cui A, Zhu Z, Hu R, et al. Genetic analysis of human parainfluenza virus type 4 associated with severe acute respiratory infection in children in Luohe City, Henan Province, China, during 2017–2018. Arch Virol. 2021;166:2585–90.

Knott AM, Long CE, Hall CB. Parainfluenza viral infections in pediatric outpatients: seasonal patterns and clinical characteristics. Pediatr Infect Dis J. 1994;13:269–73.

Laurichesse H, Dedman D, Watson JM, Zambon MC. Epidemiological features of parainfluenza virus infections: laboratory surveillance in England and Wales, 1975–1997. Eur J Epidemiol. 1999;15:475–84.

Zhao H, Harris RJ, Ellis J, Donati M, Pebody RG. Epidemiology of parainfluenza infection in England and wales, 1998–2013: any evidence of change? Epidemiol Infect. 2017;145:1210–20.

DeGroote NP, Haynes AK, Taylor C, Killerby ME, Dahl RM, Mustaquim D, et al. Human parainfluenza virus circulation, United States, 2011–2019. J Clin Virol. 2020;124: 104261.

Lau SK, Li KS, Chau KY, So LY, Lee RA, Lau YL, et al. Clinical and molecular epidemiology of human parainfluenza virus 4 infections in Hong Kong: subtype 4B as common as subtype 4A. J Clin Microbiol. 2009;47:1549–52.

Lau SK, To WK, Tse PW, Chan AK, Woo PC, Tsoi HW, et al. Human parainfluenza virus 4 outbreak and the role of diagnostic tests. J Clin Microbiol. 2005;43:4515–21.

Fairchok MP, Martin ET, Kuypers J, Englund JA. A prospective study of parainfluenza virus type 4 infections in children attending daycare. Pediatr Infect Dis J. 2011;30:714–6.

Ren L, Gonzalez R, Xie Z, Xiong Z, Liu C, Xiang Z, et al. Human parainfluenza virus type 4 infection in Chinese children with lower respiratory tract infections: a comparison study. J Clin Virol. 2011;51:209–12.

Fathima S, Simmonds K, Invik J, Scott AN, Drews S. Use of laboratory and administrative data to understand the potential impact of human parainfluenza virus 4 on cases of bronchiolitis, croup, and pneumonia in Alberta. Canada BMC Infect Dis. 2016;16:402.

Sohn YJ, Choi YY, Yun KW, Choi EH, Lee HJ. Epidemiology and clinical characteristics of parainfluenza virus type 4 in Korean children: a single center study, 2015–2017. Pediatr Infect Vaccine. 2018;25:156–64.

Gu YE, Park JY, Lee MK, Lim IS. Characteristics of human parainfluenza virus type 4 infection in hospitalized children in Korea. Pediatr Int. 2020;62:52–8.

Abedi GR, Prill MM, Langley GE, Wikswo ME, Weinberg GA, Curns AT, et al. Estimates of parainfluenza virus-associated hospitalizations and cost among children aged less than 5 years in the United States, 1998–2010. J Pediatric Infect Dis Soc. 2016;5:7–13.

Lee YJ, Kim D, Lee K, Chun JY. Single-channel multiplexing without melting curve analysis in real-time PCR. Sci Rep. 2014;4:7439.

Shi W, Cui S, Gong C, Zhang T, Yu X, Li A, et al. Prevalence of human parainfluenza virus in patients with acute respiratory tract infections in Beijing, 2011–2014. Influenza Other Respir Viruses. 2015;9:305–7.

Fry AM, Curns AT, Harbour K, Hutwagner L, Holman RC, Anderson LJ. Seasonal trends of human parainfluenza viral infections: United States, 1990–2004. Clin Infect Dis. 2006;43:1016–22.

Villaran MV, Garcia J, Gomez J, Arango AE, Gonzales M, Chicaiza W, et al. Human parainfluenza virus in patients with influenza-like illness from Central and South America during 2006–2010. Influenza Other Respir Viruses. 2014;8:217–27.

Lam TT, Tang JW, Lai FY, Zaraket H, Dbaibo G, Bialasiewicz S, et al. Comparative global epidemiology of influenza, respiratory syncytial and parainfluenza viruses, 2010–2015. J Infect. 2019;79:373–82.

Ahn JG. Epidemiological changes in infectious diseases during the coronavirus disease 2019 pandemic in Korea: a systematic review. Clin Exp Pediatr. 2022;65:167–71.

Han JY, Han SB. Febrile seizures and respiratory viruses determined by multiplex polymerase chain reaction test and clinical diagnosis. Children (Basel). 2020;7:234.

Frost HM, Robinson CC, Dominguez SR. Epidemiology and clinical presentation of parainfluenza type 4 in children: a 3-year comparative study to parainfluenza types 1–3. J Infect Dis. 2014;209:695–702.

Kim HN, Yoon SY, Lim CS, Lee CK, Yoon J. Phylogenetic analysis of human parainfluenza type 3 virus strains responsible for the outbreak during the COVID-19 pandemic in Seoul. South Korea J Clin Virol. 2022;153: 105213.

Olsen SJ, Winn AK, Budd AP, Prill MM, Steel J, Midgley CM, et al. Changes in influenza and other respiratory virus activity during the COVID-19 pandemic - United States, 2020–2021. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2021;70:1013–9.

Li L, Wang H, Liu A, Wang R, Zhi T, Zheng Y, et al. Comparison of 11 respiratory pathogens among hospitalized children before and during the COVID-19 epidemic in Shenzhen. China Virol J. 2021;18:202.

Kume Y, Hashimoto K, Chishiki M, Norito S, Suwa R, Ono T, et al. Changes in virus detection in hospitalized children before and after the severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2 pandemic. Influenza Other Respir Viruses. 2022. https://doi.org/10.1111/irv.12995.

Giraud-Gatineau A, Kaba L, Boschi C, Devaux C, Casalta JP, Gautret P, et al. Control of common viral epidemics but not of SARS-CoV-2 through the application of hygiene and distancing measures. J Clin Virol. 2022;150–151: 105163.

Kuitunen I, Artama M, Haapanen M, Renko M. Record high parainfluenza season in children after relaxation of COVID-19 restrictions in fall 2021 - a nationwide register study in Finland. Influenza Other Respir Viruses. 2022;16:613–6.

Hu W, Fries AC, DeMarcus LS, Thervil JW, Kwaah B, Brown KN, et al. Circulating trends of influenza and other seasonal respiratory viruses among the US department of defense personnel in the United States: impact of the COVID-19 pandemic. Int J Environ Res Publ Health. 2022;19:5942.

Maykowski P, Smithgall M, Zachariah P, Oberhardt M, Vargas C, Reed C, et al. Seasonality and clinical impact of human parainfluenza viruses. Influenza Other Respir Viruses. 2018;12:706–16.

Acknowledgements

The authors thank Dr. Eun Hee Han (Department of Laboratory Medicine, Daejeon St. Mary’s Hospital, Republic of Korea) for providing detailed description on the microbiological analysis.

Funding

This study was supported by the National Research Foundation of Korea (NRF) funded by the Korean Government (MSIT; 2021R1F1A1063568).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

SBH conceptualized and designed the study. JYH and SBH collected, and WS and SBH analyzed the data. JYH and SBH wrote the original manuscript, and WS critically reviewed and revised the manuscript. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate

This study was performed in line with the principles of the Declaration of Helsinki. Approval was granted by the by the Institutional Review Board of Daejeon St. Mary’s Hospital (Date 29.03.2022/No. DC22RASI0020). Acquiring informed consent was waived by the Institutional Review Board of Daejeon St. Mary’s Hospital.

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/. The Creative Commons Public Domain Dedication waiver (http://creativecommons.org/publicdomain/zero/1.0/) applies to the data made available in this article, unless otherwise stated in a credit line to the data.

About this article

Cite this article

Han, J.Y., Suh, W. & Han, S.B. Seasonal epidemiological and clinical characteristics of pediatric patients with human parainfluenza virus infection by serotype: a retrospective study. Virol J 19, 141 (2022). https://doi.org/10.1186/s12985-022-01875-2

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/s12985-022-01875-2