Abstract

Background

There is a need for objective movement assessment for clinical research trials aimed at improving gait and balance in persons with multiple sclerosis (PwMS). Wireless inertial sensors can accurately measure numerous walking and balance parameters but these measures require evaluation of reliability in PwMS. The current study determined the test-retest reliability of wireless inertial sensor measures obtained during an instrumented standing balance test and an instrumented Timed Up and Go test in PwMS.

Methods

Fifteen PwMS and 15 healthy control subjects (HC) performed an instrumented standing balance and instrumented Timed Up and Go (TUG) test on two separate days. Ten instrumented standing balance measures and 18 instrumented TUG measures were computed from the wireless sensor data. Intraclass correlation coefficients (ICC) were calculated to determine test-retest reliability of all instrumented standing balance and instrumented TUG measures. Correlations were evaluated between the instrumented standing balance and instrumented TUG measures and self-reported walking and balance performance, fall history, and clinical disability.

Results

For both groups, ICCs for instrumented standing balance measures were best for spatio-temporal measures, while frequency measures were less reliable. All instrumented TUG measures exhibited good to excellent (ICCs > 0.60) test-retest reliability in PwMS and in HC. There were no correlations between self-report walking and balance scores and instrumented TUG or instrumented standing balance metrics, but there were correlations between instrumented TUG and instrumented standing balance metrics and fall history and clinical disability status.

Conclusions

Measures from the instrumented standing balance and instrumented TUG tests exhibit good to excellent reliability, demonstrating their potential as objective assessments for clinical trials. A subset of the most reliable measures is recommended for measuring walking and balance in clinical settings.

Similar content being viewed by others

Background

Multiple sclerosis (MS) is an autoimmune disease which disrupts the myelin sheath surrounding neurons within the central nervous system [1]. It is estimated that MS affects around 350,000 patients in the United States and more than 2.3 million people worldwide [2, 3]. Symptoms of MS often include mild to severe dysfunction of motor and cognitive faculties such as muscle weakness, spasms, tremors, stiffness, fatigue, deficits in attention and executive functions, and loss of coordination and impaired balance [1]. Persons with MS (PwMS) often report difficulty in walking or standing, with up to 63% of PwMS reporting at least one fall within a 2 to 6 month period [1, 4, 5]. Unfortunately, the diverse symptomology of MS and the lack of quantitative clinical assessments of walking and balance often make it difficult to clinically assess fall risk status of PwMS.

Current clinical assessments for walking and balance difficulties in MS include measures of gait speed based on clinical tests such as the Timed Up and Go or 25 ft walk and relatively subjective measures of balance such as the Berg Balance Test [6]. Unfortunately, many of these scales are limited in their ability to accurately monitor progression of disease or intervention efficacy due to inherent subjectivity, lack of sensitivity in differentiating between groups, and poor reliability [5, 7]. Objective postural measures obtained from motion capture and posturography in PwMS have demonstrated fair to excellent validity and reliability in previous studies [8, 9]. Although effective, motion capture and force platform systems are not practical for use in most clinical settings due to high cost, difficulty of use, and lack of portability.

Wireless inertial sensors are a feasible, low cost alternative tool to assess movement and can be used in any environment [10, 11]. These devices commonly include accelerometers, gyroscopes, magnetometers, or any combination thereof, in order to objectively quantify motor patterns [12]. Such wireless sensors are highly portable with sufficient battery life allowing them to be worn for extended periods of time without constricting movement, which is especially favorable in a clinical or at-home setting [13]. The implementation of such sensors in clinical environments is of particular interest, as these sensors have the potential to enhance objectivity, sensitivity, and reliability of clinical tests [11, 14,15,16]. Sensor-based measures of postural sway and gait have been found to be sensitive to mobility deficits and reliable in persons with Parkinson’s disease and diabetic neuropathy [17,18,19,20]. These findings indicate that wireless inertial sensors can provide a reliable and sensitive measure of walking and balance in clinical settings [11, 19, 20]. Previous work has shown that wireless sensor assessments are sensitive to differences in gait and balance between healthy control subjects and PwMS [21, 22] and are reliable across trials within the same day [23,24,25,26]. However, within day reliability testing is not sufficient, as day-to-day fluctuations in performance are common in PwMS [27,28,29]. While a small subset of gait and balance measures have demonstrated between-day reliability in PwMS [25, 30], to our knowledge there are no previous studies that have determined the between-day test-retest reliability of a comprehensive set of balance and gait measures which includes spatio-temporal and frequency measures taken during an instrumented standing balance and instrumented Timed Up and Go (TUG) tests in PwMS. The lack of reliability testing currently limits the use of this technology for PwMS in clinical and research settings. Additionally, determining the between-day reliability of a comprehensive set of gait and balance measures extracted from wireless sensors will aid in sample size justifications for future studies.

Therefore, the purpose of this study was to determine the between-day test-retest reliability of wireless inertial sensor measures obtained during an instrumented standing balance test and an instrumented TUG test in PwMS. It was hypothesized that the instrumented TUG and instrumented standing balance outcome measures would exhibit strong test-retest reliability in PwMS, as has been previously found in healthy adults, in persons with Parkinson’s disease [20, 31], and in within-day reliability testing [23, 24]. To address the clinical validity of these wireless sensor measures, we also looked at the relationship between the measures and self-report walking and balance function, fall history, and clinical disability. We expected to find significant correlations between the wireless inertial sensor measures and these clinical measures.

Methods

Study design

The aim of this study was to determine the between-day test-retest reliability of wireless inertial sensor measures obtained during an instrumented standing balance test and an instrumented Timed Up and Go test in PwMS. The study was performed in a motion analysis laboratory.

Participants

Fifteen PwMS between 20 and 60 years old and 15 age and gender-matched healthy controls were recruited for this study. All PwMS had relapsing-remitting MS. PwMS were excluded if 1) they were currently prescribed symptom specific medication therapies (i.e. Fampridine) due to its direct effect on gait, 2) if they had experienced a symptom exacerbation in the previous 60 days that required treatment, 3) if they had a Kurtzke Expanded Disability Status Scale (EDSS) [32] greater than 5.5 or were unable to walk a distance of 25 ft without the assistance of a mobility aid. The EDSS assessment for PwMS was completed by a board certified neurologist (author SL) and was completed within 6 months of testing. For both healthy controls and PwMS, participants were excluded if they were women who were pregnant, breastfeeding, or within 3 months post-partum. Subjects were also excluded if they had vestibular impairments, diabetes, or a pre-existing condition that could make exercising difficult (i.e. myocardial infarction, chest pain, unusual shortness of breath, congestive heart failure, etc.). Healthy controls were free of any known neurological or musculoskeletal impairment that would have an adverse effect on their balance or gait. PwMS self-reported how many falls they experienced in the preceding 6 months, with falls being described as “an unexpected event at which the participant comes to rest on the ground, floor, or lower level [33].” Demographic and clinical details for all subjects are shown in Table 1.

Protocol

Subjects were outfitted with 6 wireless inertial sensors (Opal sensors, APDM, Portland, OR, USA) secured by elastic straps during the entirety of testing. The trunk sensor was mounted on the superior trunk over the anterior surface of the sternum, the lumbar sensor was mounted on the inferior trunk over the posterior surface at the L5 level, wrist sensors were mounted bilaterally to the posterior surface of the wrist, and ankle sensors were mounted bilaterally just superior to the ankle joint on the anterior surface of the shank.

During the instrumented standing balance assessment, all participants were instructed to maintain a quiet standing position with arms crossed over their chest and eyes open and looking straight ahead. A constant foot position of 10 cm between the heels was marked for all subjects and maintained all trials. Each trial lasted 30 s and was repeated 3 times. The median value across 3 trials for each instrumented standing balance measure was used for analysis (Table 2).

For the instrumented TUG assessment, subjects were initially seated in a chair with their backs against the seatback. At the start of the test, subjects were given the command “Walk,” which signaled the start of the test. Subjects were instructed to stand up with minimal use of their hands, walk at a normal pace to a point on the floor 7 m in front of them, turn around, walk at a normal pace back to the chair, and sit back down in the chair with minimal use of their hands. The 7-m TUG, sometimes referred to as the extended TUG, allows for a sufficient number of gait cycles necessary for the calculation of the reported gait metrics [20]. Subjects repeated this test 3 times. The median value across 3 trials for each instrumented TUG measure was used for analysis (Table 3).

All subjects were tested on two separate days with baseline testing performed on day 1 and identical follow-up testing performed on day 2 which was no more than 1 week later. The testing procedures were identical on day 1 and day 2 and no other assessments were done besides the instrumented TUG and instrumented standing balance on either day. Time of day was also kept constant between day 1 and day 2 such that testing began at the exact same time on each day.

Subjects also completed two self-report assessment questionnaires: the 12-item multiple sclerosis walking scale (MSW12) and the activities balance confidence scale (ABC). The MSW12 questionnaire is designed to measure how multiple sclerosis has affected the individual’s walking ability [34]. The ABC questionnaire is designed to measure a person’s confidence that they would not fall while performing a variety of activities [35].

Data analysis

The wireless sensors used in the current study contain two accelerometers, one gyroscope, and one magnetometer which stream data during the assessments. The wireless sensors used have a preset sample rate of 128 Hz. The two onboard accelerometers have ranges of ±16 g and ±200 g, and resolutions of 14 bits and 17.5 bits respectively. The onboard gyroscope has a range of ±2000 deg/s and a resolution of 16 bits. The onboard magnetometer has a range of ±8 Gauss and a resolution of 12 bits. All measures extracted from the instrumented standing balance and instrumented TUG tests were automatically calculated using Mobility Lab software (APDM, Portland, OR, USA). Thorough explanation and validation of the calculations used for these measures can be found in previous studies [19, 20, 36,37,38]. The metrics evaluated during the instrumented standing balance and TUG tests have been evaluated previously using a variety of wireless inertial sensor systems in both healthy and pathological populations [15, 17, 19,20,21, 39].

Statistical analysis

All statistical analyses were performed using SPSS (Version 20, SPSS Inc., Chicago, IL, USA). Test-retest reliability was assessed using intraclass correlation coefficients (ICC 2,k) [40]. The p-value and 95% confidence intervals for each ICC was also determined. ICC values were interpreted as follows: >0.75 was excellent, 0.60–0.74 was good, 0.40–0.59 was fair, <0.40 was poor [41]. Pearson’s correlations examined relationships for: instrumented standing balance measures vs. ABC questionnaire score, instrumented TUG measures vs. MSW12 questionnaire score, instrumented standing balance and instrumented TUG vs. EDSS, and instrumented standing balance and instrumented TUG vs. fall history. Pearson’s correlation coefficients were interpreted as follows: >0.70 was strong, 0.50–0.70 was moderate, 0.30 – 0.50 was weak [42]. An alpha level of 0.05 was used for all statistical tests.

Results

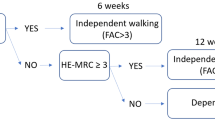

MS subjects’ EDSS scores ranged from 1 to 3.5 (Table 1). Descriptive statistics, ICCs and 95% confidence intervals for all instrumented standing balance and instrumented TUG measures are shown in Tables 4 and 5 respectively. All instrumented TUG measures displayed excellent test-retest reliability in PwMS. All but one instrumented TUG measure (stride length ICC = 0.696) displayed excellent (ICC > 0.75) test-retest reliability in HC. Examples of the walking acceleration time series are shown in Fig. 1.

For instrumented standing balance measures, there was a larger range of ICC values for both PwMS and HC. In PwMS, all instrumented standing balance measures, except one (frequency dispersion ICC = 0.438), displayed excellent test-retest reliability. In HC, all measures displayed excellent test-retest reliability except three measures that displayed good test-retest reliability (range ICC = 0.731, mean velocity ICC = 0.699, 95% frequency ICC = 0.672) and one measure displayed poor test-retest reliability (frequency dispersion ICC = 0.151). Examples of the standing balance acceleration time series are shown in Fig. 2.

There were no significant correlations between instrumented standing balance outcome measures and the ABC questionnaire scores (Table 6), or between the instrumented TUG outcome measures and the MSW12 questionnaire scores (Table 7). EDSS scores were moderately correlated with four instrumented standing balance variables; distance (r = −0.533), RMS (r = −0.549), range (r = −0.543), and mean frequency (r = 0.538) (Table 6). EDSS scores were moderately correlated with four instrumented TUG variables; stride velocity (r = 0.609), cadence (r = 0.674), cycle time (r = −0.655), and shank velocity (r = 0.624) (Table 7). There were no significant correlations between instrumented standing balance outcome measures and self-reported number of falls (Table 6). Self-reported number of falls was moderately correlated with stride velocity (r = −0.557), cadence (r = −0.641) and cycle time (r = 0.652) (Table 7).

Discussion

The current study determined the between-day test-retest reliability of a comprehensive set of wireless sensor measures from instrumented standing balance test and an instrumented Timed-Up and Go test on PwMS. Almost all of the instrumented standing balance and instrumented TUG measures exhibited good to excellent reliability across the two separate testing days. Previous work has shown that wireless sensor based assessments are sensitive to gait and balance deficits in healthy adults [43], patients with Parkinson’s disease [19, 20], and PwMS [21, 22]. Additionally, many of the measures obtained from these wireless sensors exhibit good to excellent test-retest reliability in aging adults [26] and patients with Parkinson’s disease [19, 20]. To date, within-day reliability studies using wireless sensor measures have been performed in PwMS [23, 24], but between-day testing has only been performed in a small subset of wireless sensor measures [25, 30]. The current analysis builds upon previous work by determining the between-day reliability of a comprehensive set of gait and balance measures in persons with multiple sclerosis.

Our results provide support for using wireless inertial sensors to reliably measure gait and balance in persons with multiple sclerosis. Our results show that the test-retest reliability for instrumented standing balance outcome measures was best for spatio-temporal measures such as path length and jerk, while the frequency measures such as frequency dispersion were less reliable. The lowered reliability in the frequency measures during the standing balance assessment has been observed in previous work [19, 44] and may be due to variations in subjects’ balance strategies between the testing sessions. Subjects’ foot positioning was normalized between testing sessions, however this does not fully control for balance strategy differences such as swaying about the ankle 1 day, or using the hip more on another day. While these different strategies may induce changes in frequency content of sway, both allow the subjects to achieve sufficient balance performance. Almost all instrumented TUG measures exhibited excellent test-retest reliability, with the only exception being stride length in HC, which showed good test-retest reliability.

The ICCs for the HC subjects were slightly lower than those for PwMS. Previous work has shown similar trends, with HC subjects having lower ICCs compared to patients with Parkinson’s disease [19]. There is, however, substantial overlap of the 95% confidence intervals between the two groups for every ICC value indicating that the ICC differences are likely not significant. Nevertheless, this trend is likely due to a higher amount of intra-subject variability in our MS subjects’ walking and balance performance without an increase in performance variability between the two testing sessions. Our descriptive statistics also reflect increased variability as the standard deviations for the instrumented standing balance and instrumented TUG measures tended to be larger in PwMS. Previous work has noted that PwMS have altered variability during gait potentially due to deficits such as gait ataxia, which causes problems in the control of gait and results in an increase in random variability during gait [10, 22]. Previous work examining clinical balance assessments, questionnaires, and a subset of wireless sensor assessments have also shown good to excellent test-retest reliability in PwMS [30, 45], which are in agreement with the current findings.

We expected to find correlations between some of the wireless inertial sensor measures and the questionnaires, fall history, and clinical disability. However there were no significant correlations found between any of the instrumented standing balance measures and. the ABC questionnaire or between the instrumented TUG measures and MSW12 questionnaire. The ABC questionnaire is designed to assess a person’s balance confidence in everyday life, while the MSW12 questionnaire is designed to measure how MS has affected the individual’s walking [34, 35]. Lack of correlation between wireless inertial sensor measures and self-report questionnaires could be due to the subjective questions and lack of sensitivity of the questionnaires [46]. Since the PwMS who participated in the current study were classified with mild impairment from their EDSS score, similar to previous studies [21, 47], it is possible the questionnaires were simply not sensitive enough to distinguish small inter-subject differences. Specifically, even the most impaired subject in our sample may have had very similar self-perceived balance and mobility scores compared to the least impaired subject in our sample. However, there were significant correlations between both instrumented standing balance measures (distance, RMS, range, and mean frequency) and instrumented TUG measures (stride velocity, cadence, cycle time, and shank velocity) and EDSS which indicates good clinical validity between some wireless inertial sensor measures and the gold standard clinical disability scale. For example, higher cadence measured from the instrumented TUG assessment in PwMS was correlated with a higher EDSS as assessed by a neurologist, indicating a relationship between these measures. Three instrumented TUG measures (stride velocity, cadence, and gait cycle time) also showed significant correlations with fall history. Because previous history of falls is a primary predictor of future falls [7], it is possible that stride velocity, cadence, gait cycle time measured during the instrumented TUG could be monitored on a regular basis and used to identify changes in individuals’ functional status or risk of future falls. Longitudinal studies evaluating these outcomes in PwMS are needed to confirm the use of wireless inertial sensor measures as fall predictors.

The current study has a relatively small sample size and the PwMS were high functioning with low disability, which limits the ability to generalize the findings of the current study to all individuals with MS. However, similar previous studies have used similar sample sizes [19, 25, 26], and even within this small sample, 26 out of 27 metrics taken from the instrumented standing balance and instrumented TUG assessments exhibited good to excellent reliability (ICC range 0.693–0.962).

Conclusions

The current study provides important information concerning the test-retest reliability of measures extracted from an instrumented TUG and instrumented standing balance in PwMS. The test-retest reliability results from the current study can be used in future studies when power estimations are needed to determine a required sample size. A majority of the outcome measures from the instrumented TUG and instrumented standing balance exhibited good to excellent reliability. For PwMS, the mean distance from the center of pressure (distance) was the most reliable outcome measure from the instrumented standing balance assessment, while range of motion of the trunk in the frontal plane (trunk front RoM) was the most reliable outcome measure from the instrumented TUG. Overall these assessments provide reliable measures of walking and postural control which can be used as screening protocols or mobility assessment outcome measures.

Abbreviations

- ABC:

-

Activities balance confidence scale

- BMI:

-

Body mass index

- EDSS:

-

Kurtzke Expanded Disability Status Scale

- HC:

-

Healthy control subjects

- ICC:

-

Intraclass correlation coefficients

- MS:

-

Multiple sclerosis

- MSW12:

-

12-item multiple sclerosis walking scale

- PwMS:

-

Persons with multiple sclerosis

- Trunk front RoM:

-

Range of motion of the trunk in the frontal plane

- TUG:

-

Timed Up and Go

References

Compston A, Coles A. Multiple sclerosis. Lancet. 2008;372:1502–17.

Who Gets MS? [http://www.nationalmssociety.org/What-is-MS/Who-Gets-MS]. Accessed 12 May 2016.

Noseworthy JH, Lucchinetti C, Rodriguez M, Weinshenker BG. Multiple sclerosis. N Engl J Med. 2000;343:938–52.

Cattaneo D, De Nuzzo C, Fascia T, Macalli M, Pisoni I, Cardini R. Risks of falls in subjects with multiple sclerosis. Arch Phys Med Rehabil. 2002;83:864–7.

Nilsagard Y, Lundholm C, Denison E, Gunnarsson LG. Predicting accidental falls in people with multiple sclerosis -- a longitudinal study. Clin Rehabil. 2009;23:259–69.

Assessment and Intervention [http://www.nationalmssociety.org/For-Professionals/Clinical-Care/Managing-MS/Rehabilitation/Rehabilitation-Paradigm/Assessment-and-Intervention]. Accessed 12 May 2016.

Cameron MH, Thielman E, Mazumder R, Bourdette D. Predicting Falls in People with Multiple Sclerosis: Fall History Is as Accurate as More Complex Measures. Mult Scler Int. 2013;2013:1-8.

Karst GM, Venema DM, Roehrs TG, Tyler AE. Center of pressure measures during standing tasks in minimally impaired persons with multiple sclerosis. J Neurol Phys Ther. 2005;29:170–80.

Wajda DA, Motl RW, Sosnoff JJ. Three-month test-retest reliability of center of pressure motion during standing balance in individuals with multiple sclerosis. Int J MS Care. 2016;18:59–62.

Huisinga JM, Mancini M, St George RJ, Horak FB. Accelerometry reveals differences in gait variability between patients with multiple sclerosis and healthy controls. Ann Biomed Eng. 2013;41:1670–9.

Mancini M, King L, Salarian A, Holmstrom L, McNames J, Horak FB: Mobility Lab to Assess Balance and Gait with Synchronized Body-worn Sensors. J Bioeng Biomed Sci. 2011;Suppl 1:007.

Sabatini AM. Estimating three-dimensional orientation of human body parts by inertial/magnetic sensing. Sensors (Basel). 2011;11:1489–525.

Shull PB, Jirattigalachote W, Hunt MA, Cutkosky MR, Delp SL. Quantified self and human movement: a review on the clinical impact of wearable sensing and feedback for gait analysis and intervention. Gait Posture. 2014;40:11–9.

Marschollek M, Rehwald A, Wolf KH, Gietzelt M, Nemitz G, zu Schwabedissen HM, Schulze M. Sensors vs. experts - a performance comparison of sensor-based fall risk assessment vs. conventional assessment in a sample of geriatric patients. BMC Med Inform Decis Mak. 2011;11:48.

Solomon AJ, Jacobs JV, Lomond KV, Henry SM. Detection of postural sway abnormalities by wireless inertial sensors in minimally disabled patients with multiple sclerosis: a case–control study. J Neuroeng Rehabil. 2015;12:74.

Mancini M, Horak FB. The relevance of clinical balance assessment tools to differentiate balance deficits. Eur J Phys Rehabil Med. 2010;46:239–48.

Horak FB, Mancini M. Objective biomarkers of balance and gait for Parkinson’s disease using body-worn sensors. Mov Disord. 2013;28:1544–51.

Najafi B, Horn D, Marclay S, Crews RT, Wu S, Wrobel JS. Assessing postural control and postural control strategy in diabetes patients using innovative and wearable technology. J Diabetes Sci Technol. 2010;4:780–91.

Mancini M, Salarian A, Carlson-Kuhta P, Zampieri C, King L, Chiari L, Horak FB. ISway: a sensitive, valid and reliable measure of postural control. J Neuroeng Rehabil. 2012;9:59.

Salarian A, Horak FB, Zampieri C, Carlson-Kuhta P, Nutt JG, Aminian K. iTUG, a sensitive and reliable measure of mobility. IEEE Trans Neural Syst Rehabil Eng. 2010;18:303–10.

Spain RI, Mancini M, Horak FB, Bourdette D. Body-worn sensors capture variability, but not decline, of gait and balance measures in multiple sclerosis over 18 months. Gait Posture. 2014;39:958–64.

Spain RI, St George RJ, Salarian A, Mancini M, Wagner JM, Horak FB, Bourdette D. Body-worn motion sensors detect balance and gait deficits in people with multiple sclerosis who have normal walking speed. Gait Posture. 2012;35:573–8.

Greene BR, Healy M, Rutledge S, Caulfield B, Tubridy N. Quantitative assessment of multiple sclerosis using inertial sensors and the TUG test. Conf Proc IEEE Eng Med Biol Soc. 2014;2014:2977–80.

Greene BR, Rutledge S, McGurgan I, McGuigan C, OConnell K, Caulfield B, Tubridy N. Assessment and classification of early-stage multiple sclerosis with inertial sensors: comparison against clinical measures of disease state. IEEE J Biomed Health Inform. 2015;19:1356–61.

Hale L, Williams K, Ashton C, Connole T, McDowell H, Taylor C. Reliability of RT3 accelerometer for measuring mobility in people with multiple sclerosis: pilot study. J Rehabil Res Dev. 2007;44:619–27.

Smith E, Walsh L, Doyle J, Greene B, Blake C. The reliability of the quantitative timed up and go test (QTUG) measured over five consecutive days under single and dual-task conditions in community dwelling older adults. Gait Posture. 2016;43:239–44.

Albrecht H, Wotzel C, Erasmus LP, Kleinpeter M, Konig N, Pollmann W. Day-to-day variability of maximum walking distance in MS patients can mislead to relevant changes in the Expanded Disability Status Scale (EDSS): average walking speed is a more constant parameter. Mult Scler. 2001;7:105–9.

Morris ME, Cantwell C, Vowels L, Dodd K. Changes in gait and fatigue from morning to afternoon in people with multiple sclerosis. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry. 2002;72:361–5.

Crenshaw SJ, Royer TD, Richards JG, Hudson DJ. Gait variability in people with multiple sclerosis. Mult Scler. 2006;12:613–9.

Motta C, Palermo E, Studer V, Germanotta M, Germani G, Centonze D, Cappa P, Rossi S, Rossi S. Disability and fatigue can be objectively measured in multiple sclerosis. PLoS ONE. 2016;11:e0148997.

Mancini M, Carlson-Kuhta P, Zampieri C, Nutt JG, Chiari L, Horak FB. Postural sway as a marker of progression in Parkinson’s disease: a pilot longitudinal study. Gait Posture. 2012;36:471–6.

Kurtzke JF. Rating neurologic impairment in multiple sclerosis: an expanded disability status scale (EDSS). Neurology. 1983;33:1444–52.

Lamb SE, Jorstad-Stein EC, Hauer K, Becker C. Development of a common outcome data set for fall injury prevention trials: the Prevention of Falls Network Europe consensus. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2005;53:1618–22.

Hobart JC, Riazi A, Lamping DL, Fitzpatrick R, Thompson AJ. Measuring the impact of MS on walking ability: the 12-Item MS Walking Scale (MSWS-12). Neurology. 2003;60:31–6.

Veltro F, Morosini P, Gigantesco A, Casacchia M, Roncone R, Dell’Acqua G, Chiaia E, Balbi A, De Stefani R, Cesari G. A new self-report questionnaire called “ABC” to evaluate in a clinical practice the aid perceived from services by relatives, needs and family burden of severe mental illness. Clin Pract Epidemiol Ment Health. 2007;3:15.

Salarian A, Russmann H, Vingerhoets FJ, Dehollain C, Blanc Y, Burkhard PR, Aminian K. Gait assessment in Parkinson’s disease: toward an ambulatory system for long-term monitoring. IEEE Trans Biomed Eng. 2004;51:1434–43.

Salarian A, Russmann H, Vingerhoets FJ, Burkhard PR, Aminian K. Ambulatory monitoring of physical activities in patients with Parkinson’s disease. IEEE Trans Biomed Eng. 2007;54:2296–9.

Mancini M, Horak FB, Zampieri C, Carlson-Kuhta P, Nutt JG, Chiari L. Trunk accelerometry reveals postural instability in untreated Parkinson’s disease. Parkinsonism Relat Disord. 2011;17:557–62.

Coulthard JT, Treen TT, Oates AR, Lanovaz JL. Evaluation of an inertial sensor system for analysis of timed-up-and-go under dual-task demands. Gait Posture. 2015;41:882–7.

Weir JP. Quantifying test-retest reliability using the intraclass correlation coefficient and the SEM. J Strength Cond Res. 2005;19:231–40.

Fleiss JL. The Design and Analysis of Clinical Experiments. New York: Wiley; 1986.

Hinkle DE, Wiersma W, Jurs SG. Applied Statistics for the Behavioral Sciences. Boston: Houghton Mifflin; 2003.

Greene BR, O’Donovan A, Romero-Ortuno R, Cogan L, Scanaill CN, Kenny RA. Quantitative falls risk assessment using the timed up and go test. IEEE Trans Biomed Eng. 2010;57:2918–26.

Lafond D, Corriveau H, Hebert R, Prince F. Intrasession reliability of center of pressure measures of postural steadiness in healthy elderly people. Arch Phys Med Rehabil. 2004;85:896–901.

Cattaneo D, Jonsdottir J, Repetti S. Reliability of four scales on balance disorders in persons with multiple sclerosis. Disabil Rehabil. 2007;29:1920–5.

Cattaneo D, Regola A, Meotti M. Validity of six balance disorders scales in persons with multiple sclerosis. Disabil Rehabil. 2006;28:789–95.

Confavreux C, Vukusic S. Natural history of multiple sclerosis: a unifying concept. Brain. 2006;129:606–16.

Acknowledgements

We thank Olivia Dykes for scheduling and assisting with data collections.

Funding

This work was supported by the National Multiple Sclerosis Society RG 4914A1/2, the NIH National Center for Advancing Translational Science 1KL2TR00011, and the NIH Ruth L. Kirschstein National Research Service Award T32 HD057850 from the National Institute of Child Health and Human Development.

Availability of data and materials

The datasets used and/or analyzed during the current study available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

Authors’ contributions

Study design – JC, FH, JH; Data collection – JC, AB; Data analysis – JC, AB; Interpretation of results – JC, SL, JH; Drafting the manuscript – JC, JH; Revising the manuscript – AB, SL, FH, JH. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Competing interests

Dr. Horak and OHSU have significant financial interests in APDM, a company that might have a commercial interest in the results of this research and technology. This potential conflict of interest has been reviewed and managed by OHSU and the Integrity Oversight Council.

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Ethics approval and consent to participate

The Human Subjects Committee of the University of Kansas Medical Center approved the current study (IRB #13495). Written informed consent was given by the participants in accordance with ethical guidelines.

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/), which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made. The Creative Commons Public Domain Dedication waiver (http://creativecommons.org/publicdomain/zero/1.0/) applies to the data made available in this article, unless otherwise stated.

About this article

Cite this article

Craig, J.J., Bruetsch, A.P., Lynch, S.G. et al. Instrumented balance and walking assessments in persons with multiple sclerosis show strong test-retest reliability. J NeuroEngineering Rehabil 14, 43 (2017). https://doi.org/10.1186/s12984-017-0251-0

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/s12984-017-0251-0