Abstract

Introduction

The novel coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) has quickly become a worldwide threat to human health and has significantly impacted people’s lives and changed their lifestyles and health behaviors. This study aims to assess lifestyle and health-related behaviors (LHBs) and associated factors among the general population in Lebanon during the COVID-19 pandemic.

Methods

An online cross-sectional study was conducted among 403 Lebanese adults. The study questionnaire was developed on Google Forms in English and Arabic. It included self-reported questions about sociodemographic characteristics, COVID-19, and perceived behavioral changes (smoking, alcohol consumption, sexual and hygiene behaviors, and intake of nutritional supplements and immunity-boosting foods). It also comprised three scales, i.e., the Lifestyle and Health Behaviors questionnaire (LHB-17), the WHO-5 Well-being Index, and the Fear of COVID-19 scale (FCV-19S).

Results

The mean age of participants was 29.74 ± 10.81 years, with 51.2% females. Most participants reported that COVID-19 negatively affected their LHBs, mainly diet, sleep, and psychological well-being, while physical activity aspects remained unaffected. Female gender (Unstandardized Beta (ß) = − 2.336), living in Lebanon (ß = − 7.502), nargileh smoking (ß = − 3.433), high BMI (ß = − 0.263), and increased daily usage of electronic devices during the COVID-19 lockdown (ß = − 0.853) were significantly associated with lower LHB-17 scores, indicating worsened LHB. However, living in urban areas (ß = 2.464), employment status (ß = 1.920), good overall health (ß = 3.543), a higher quality of life (ß = 0.204), and unaffected physical (ß = 2.101) and mental (ß = 1.586) health during the COVID-19 lockdown were all significantly associated with higher LHB-17 scores, reflecting positive LHB.

Conclusion

Lebanese adults reported several unfavorable lifestyle changes and psychological problems during the lockdown due to COVID-19, particularly affecting women, non-workers, waterpipe smokers, electronic device heavy users, people of lower socioeconomic status, and those with chronic diseases. Health promotion strategies are needed to assess negative changes both in physical and mental health and maintain as many positive health-related behaviors as possible among the Lebanese population.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

1 Introduction

The novel coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) has quickly become a worldwide threat to human health [1], drastically impacting people’s lives and bringing about a sudden and radical change in their daily routine and lifestyle [2]. Considering the COVID-19 outbreak, social distancing and preventive measures were recommended to combat and reduce contamination risks [3]. These measures include hand hygiene, an essential step in preventing the transmission of pathogens and reducing the risk of acquired infections [4].

Although it is the cornerstone of curbing the pandemic, confinement induces lifestyle behavior changes, promoting sedentary and poor dietary habits, as evidenced by several studies [2, 5,6,7,8,9]. Physical activity is reduced due to compulsory home isolation and the lockdown imposed on various public and social settings [8]. Indeed, community mobility data from 15 countries revealed that the time spent in places associated with physical activity, such as parks, beaches, and community gardens, was lower during the COVID-19 lockdown. Conversely, the time spent at home watching television (TV), playing video games, and using electronic devices has increased during confinement, where people tend to go to bed later and wake up later, which further explains the limited physical activity [7].

Furthermore, social distancing caused by home confinement increases the risk of psychosocial disorders due to the limited communication and interaction with society [10, 11]. Psychological and emotional disorders manifested by depression, anxiety, and frustration are common during COVID-19, as it is still an ongoing pandemic surrounded by controversies in terms of mode of transmission and treatment. Thus, individuals tend to experience greater psychosocial and emotional pressures during the lockdown, associated with unhealthy lifestyle behaviors such as physical and social inactivity, an unhealthy diet, and poor sleep quality [11, 12]. A multi-centered international study has shown that social isolation during the COVID-19 lockdown has harmful effects on mental wellness, characterized by increased anxiety and stress [13].

People who experience psychological disorders and stressful events during the COVID-19 lockdown tend to consume more unhealthy foods rich in fat and sugar to relieve feelings of tension, anger, and confusion [10]. Furthermore, due to stringent lockdown restrictions, households would stockpile ultra-processed and high-calorie foods, increasing unhealthy food intake [14]. The COVID-19 lockdown has affected weight gain due to the limited access to daily grocery shopping coupled with reduced consumption of fresh foods and increased intake of processed convenience foods [2], particularly those high in sugar, to help cope with COVID-19 psychological distress and improve the mood [15, 16].

As for the association between COVID-19 and smoking behaviors, it is complex and bidirectional. While some studies suggested that COVID-19 might lead to reduced or even cessation of smoking due to the fear of contracting the virus and the increased risk of hospitalization among smokers [17,18,19,20,21], others indicated that mental stress and anxiety are eased through smoking, resulting in increased consumption [22].

In Lebanon, the COVID-19 outbreak occurred together with an unprecedented economic crisis, with the first confirmed case reported on February 21, 2020. As of this date, the Lebanese government has implemented preventive measures to curb the spread of the disease. However, the steadily increasing COVID-19 cases have mandated several sterner interventions, including curfews and total lockdowns [23].

Several studies have assessed the effects of the COVID-19 pandemic on Lebanese adults, covering mental health, domestic violence, weight change, stress, and anxiety [24,25,26,27]. Their findings revealed that the fear of COVID-19 was associated with a negative weight perception [25] and higher stress and anxiety, particularly in women [26]. Furthermore, extended confinement was associated with a higher weight change perception [25]. These studies have addressed some of the factors affected by the COVID-19 pandemic; however, none have evaluated lifestyle and health-related behavior changes among Lebanese adults. Understanding the associations between lifestyle risk factors and COVID-19 is essential to identifying people at risk of unhealthy behaviors during the lockdown since it is hypothesized that lifestyle measures and health-related behaviors are altered during the COVID-19 pandemic.

Therefore, this study aimed to assess self-reported changes in lifestyle and health-related behaviors (LHBs) such as daily habits (hygiene, smoking, alcohol, and work), dietary habits (intake, meal pattern, and snack consumption), physical activity (duration and type), sleep patterns (length and quality), psychological problems (physical and emotional exhaustion, irritability, and tension), and sexual behaviors among the Lebanese adults during the COVID-19 pandemic. It also sought to examine the factors associated with LHBs.

2 Materials and methods

2.1 Study design and sampling

An online cross-sectional study conducted between January 9 and January 28, 2021, enrolled 403 Lebanese adults using the snowball sampling technique. All people over 18 with access to the internet were eligible to participate. The study questionnaire developed on Google Forms was self-administered, anonymous, and available in English and Arabic. The survey link was distributed through various social media platforms (WhatsApp, Facebook, and Instagram) to reach participants from all Lebanese districts (Beirut, Mount Lebanon, North, Beqaa/Baalbeck/Hermel, and South/Nabatieh). Participants were encouraged to share it with friends and people they know.

The first page of the questionnaire included explanations of the study objectives and the following informed consent statement: “Completing the questionnaire requires 10 to 15 min and indicates your consent to participate.” Participation in this study was voluntary, and participants received no incentive in exchange for their participation.

2.2 Sample size calculation

The Epi Info™ software (Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, Epi Info™) was used to calculate the required sample size [28]. The minimum sample calculated was 350 participants based on a population size of 3,413,308 Lebanese adults (according to the population estimates of 2019–2020 from the Central Administration of Statistics) [29], an alpha error of 5%, a power of 80%, a confidence level of 95%, and an expected frequency of behavior changes due to COVID-19 of 35% in our population, as per a recent study on eating habits and lifestyle behaviors during the COVID-19 pandemic in 18 countries from the Middle East and North Africa region, including Lebanon, which that represented 11.5% of the overall sample [30]. The final sample size comprised 403 participants to allow for adequate power for multivariable statistical analyses.

2.3 Questionnaire

The questionnaire consisted of three sections and included structured closed-ended questions.

The first part of the questionnaire clarified the sociodemographic features of participants: age, gender, marital status, education level, family monthly income, the number of people living in the same house, the number of rooms in the house, occupation status, the region of residence, and religion. The household crowding index was calculated by dividing the number of people living in the house by the number of rooms, excluding the kitchen and bathrooms. The family monthly income, in Lebanese pounds (LBP), was divided into four levels: no income, low (< 1,500,000 LBP), intermediate (1,500,000–3,000,000 LBP), and high income (> 3,000,000 LBP). Two additional questions, rated on a 5-point Likert scale from 0 (not worried at all) to 5 (extremely worried), assessed financial distress by measuring how worried participants were about their current financial situation and being unable to meet regular monthly living expenses.

The second part consisted of questions related to COVID-19, such as direct or potential contact with someone with COVID-19, having been diagnosed or tested positive for COVID-19, family history of COVID-19, and the changes in hours spent working/studying/using electronic devices (screen time), salary/income, and weight during the COVID-19 pandemic.

The third part of the questionnaire consisted of three scales and questions about health-related behavior self-reported changes, as follows.

2.3.1 The lifestyle and health behaviors questionnaire (LHB-17)

Based on a validated questionnaire [31], this 17-item newly constructed questionnaire (LHB-17) is a short, concise, and user-friendly tool used to assess lifestyle and health-related behavior self-reported perceived changes during the COVID-19 pandemic by the general population. It covers all essential aspects of LHBs, including dietary habits (intake, meal pattern, and snack consumption), physical activity (duration and type), sleep (length and quality), and psychological health (irritability, stress, and anxiety).

Diet-related items (1–9) assessed the consumption of main meals, snacks, a healthy and balanced diet (including whole grains, fruits, vegetables, eggs, and nuts), and unhealthy foods (fried food, fast food, and sugar-sweetened products). Physical activity-related items (10 to 12) assessed participation in aerobic exercise, household-related activities (cooking, laundry, and cleaning), and leisure-related activities (indoor/outdoor activities, walking, and gardening). Two questions (13 and 14) assessed sleep length and levels of stress and anxiety. The last three questions (15–17) evaluated psychological health self-declared changes, i.e., irritability and physical and emotional exhaustion. All items were graded on a 5-point Likert scale: (a) Significantly increased; (b) Slightly increased; (c) Grossly similar; (d) Slightly decreased; (e) Significantly decreased.

The total score was calculated by summing responses to all items, depending on change outcomes; grades could be negative (tending for the worse) or positive (tending for the better).

Items 1, 2, 6, 7, 8, 9, 14, 15, 16, and 17, considered negative behaviors, were scored from 2 (significantly decreased), 1 (slightly decreased), 0 (grossly similar), -1 (slightly increased), to -2 (significantly increased). Items 4, 5, 10, 11, and 12, reflecting positive behaviors, were scored from 2 (significantly increased), 1 (slightly increased), 0 (grossly similar), -1 (slightly decreased), to -2 (significantly decreased). Items 3 and 13, assessing changes in meal and snack portions and hours of sleep during COVID-19, respectively, were rated assuming regular pre-pandemic portion and sleep levels, using a scale of 0 (grossly similar), − 1 (slightly increased/decreased), and − 2 (significantly increased/decreased).

Higher LHB-17 scores indicate improved LHBs, while lower LHB-17 scores reflect worsened LHBs (αCronbach = 0.71).

2.3.2 The WHO-5 well-being index

The WHO-5 Well-Being Index, developed by the World Health Organization (WHO), is a 5-item tool that measures mental well-being during the past two weeks [32, 33]. The Arabic-validated version (WHO-5-A) was used in this study [34]. The raw score calculated by summing the five answers ranges from 0 to 25, with higher scores indicating increased well-being (αCronbach = 0.95). The WHO-5-A is a helpful screening tool to detect depressive episodes among Lebanese adults at a cut-off point of less than 13. Therefore, a score below 13 reflects poor well-being and is an indication for testing for possible depression [34].

2.3.3 Fear of COVID-19 scale (FCV-19S)

The FCV-19S is a 7-item scale developed to assess the fear of COVID-19 among the general population [35]. The Arabic-validated version of the FCV-19S was used in this study [36]. Items are graded on a 5-point Likert scale from 1 (strongly disagree) to 5 (strongly agree). The total score is calculated by adding up each item score, where higher scores indicate a greater fear of COVID-19 (αCronbach = 0.91) [35].

2.3.4 Questions related to other behavior changes

Questions related to risky behaviors, such as smoking, alcohol consumption, and sexual behaviors, were included to assess changes that occurred during COVID-19 and were self-reported by the study population. The questions were: “Did your smoking behavior change during the COVID-19 pandemic?”; “Did your alcohol drinking behavior change during the COVID-19 pandemic?”; “During the COVID-19 pandemic, have your sexual and intimate behaviors changed? (e.g., dating, kissing, cuddling, spending private time with your partner, having sexual intercourse with your partner)”; and “During the COVID-19 pandemic, have your sexual desire changed?”. These questions were rated as follows: (a) Significantly increased; (b) Slightly increased; (c) Grossly similar; (d) Slightly decreased; (e) Significantly decreased. The option “I prefer not to answer” was added for sexuality-related questions. For smoking and alcohol consumption, two additional answers per behavior were possible, i.e., “I have recently started smoking/drinking alcohol” and “I don’t smoke/drink alcohol.”

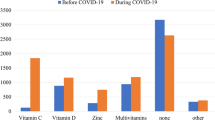

Moreover, four questions evaluated reported changes in hygiene behaviors during the COVID-19 pandemic, i.e., handwashing, surface and material disinfection, respiratory etiquette (using a face mask and applying cough etiquette), social distancing, and avoiding crowded places. Two questions assessed reported changes in nutritional supplements and immunity-boosting food intake (lemon, turmeric, garlic, citrus fruits, and green leafy vegetables) during the COVID-19 pandemic. All these questions were graded on a 5-point Likert scale, as follows: (a) Significantly increased; (b) Slightly increased; (c) Grossly similar; (d) Slightly decreased; (e) Significantly decreased.

2.4 Translation procedure

The LHB-17 scale was translated from English into Arabic using the forward and backward translation method. One of the authors performed the translation from English into Arabic, and another author did the back-translation. Discrepancies were resolved by consensus between the original English version and the translated one.

2.5 Statistical analysis

Data analysis was done using SPSS software version 21. A “weighting” variable was created to adjust for the composition of our sample (especially the over- or under-representation of gender and governorate distribution), aiming at reflecting the Lebanese adult population structure. Gender and governorate distribution were taken from the Central Administration of Statistics in Lebanon, and the weighting coefficient allowed adjusting the sample percentages to those of the Lebanese population while keeping the same sample size [37].

Cronbach’s alpha was calculated to confirm the reliability of the scales used; scales with a coefficient value of 0.7 or higher are considered internally consistent [38].

Afterward, descriptive statistics were performed to represent the participants’ characteristics and LHBs self-reported changes during the COVID-19 pandemic and were expressed as frequencies and percentages for categorical variables and as means and standard deviations (SD) for continuous variables. Since the sample was higher than 300, a visual inspection of the histogram enabled a check for normality of continuous variables, coupled with skewness and a kurtosis lower than 2 in absolute value. The associations between LHBs self-declared changes and participants’ characteristics and associated health factors were compared with the Pearson correlation for continuous variables and the Student t-test or ANOVA F test for categorical variables with two or more levels, respectively. The Bonferroni test was used for multiple comparisons to control the overall significance level for some sets of inferences performed as a follow-up to the ANOVA.

A multivariate analysis was conducted using a three-level nested model analysis, taking the LHB-17 scale as the dependent variable. The first level included sociodemographic and work-related variables. In the second level, the LHBs were added to the significant variables found in the first level. The third level consisted of all the COVID-19-related variables added to the variables found significant in the first and second levels. The three-level nested models were used to manually select and assess three homogeneous groups of variables’ effect on the dependent variable, allowing a deeper understanding of the causal pathway before one full model that includes all independent variables is displayed; this method offers an overall better understanding of the underlying process that generated the data [39]. The stepwise method was used at each level simultaneously to remove the weakest correlated variables and develop a model that best explains the distribution. All variables that showed a p-value < 0.2 in the bivariate analysis were included as covariates in the related levels. Unstandardized beta and 95% CIs were used to quantify the associations between variables and LHBs self-reported changes. A p-value less than 0.05 was considered significant.

3 Results

3.1 Descriptive analysis

Our sample consisted of 403 participants; the mean age was 29.74 ± 10.81 years, with 51.2% females and 48.8% males. Most participants were single (64.8%), had a university degree (85.2%), and lived in an urban area (68.6%). The mean household crowding index was 1.11 ± 0.88. Of the total sample, 34.2% had low to no income, 25.5% had intermediate income, and 40.3% had a high income. Moreover, 44.4% reported a decrease in salary during the COVID-19 pandemic, and 34.6% declared being very or extremely worried about their current financial situation. About half of the participants had full-time jobs (48.8%) and were mainly working/studying from home (53.2%) during the lockdown period. Also, 37.2% were healthcare professionals, and 44.5% had direct/potential contact with confirmed/suspected COVID-19 patients. More than half of the participants (51.6%) had a normal weight range (BMI = 24.17 ± 4.41 kg/m2), and only 11.3% were obese (BMI ≥ 30 kg/m2). Also, 32.4% reported weight gain during the COVID-19 pandemic, 31.7% lost weight, and 28.1% maintained weight. Most participants stated they had a significant (52%) and slight (23.7%) increase in sitting and screen time (TV and electronic devices). When asked about their overall health state, the majority reported a good state (49.5%), and only 2.7% reported a poor state of health.

Regarding hygiene, most participants reported significantly or slightly increased changes in their behaviors during the COVID-19 pandemic in terms of handwashing (86%), surface and material disinfection (87.2%), respiratory etiquette (90.9%), and social distancing (88.2%).

Only 26.2% of the participants were previously diagnosed with COVID-19, while 55.5% reported a history of COVID-19 in the family. Moreover, 9.2% were diagnosed/screened for depression/anxiety due to COVID-19 by a doctor, and only 13.4% had chronic diseases.

In this study, 24.3% of the surveyed individuals smoked cigarettes, 20.4% smoked nargileh, 1.4% started smoking during the pandemic, and 61.8% of those who already smoked slightly and significantly increased smoking. Moreover, 43.2% of participants drank alcohol, 1.1% of the participants started drinking during the pandemic, and 37.6% of those who already drank slightly and significantly increased their alcohol drinking.

Lastly, 29.6% of the surveyed individuals reported they had slightly and significantly decreased their sexual behaviors during the COVID-19 pandemic, such as dating, kissing, cuddling, spending intimate time, or having sexual intercourse with their partner, and 15.5% had slightly and significantly decreased sexual desire.

3.2 Description of the scales used in the study

Table 1 describes all the scales used in this study in terms of mean, standard deviation (SD), median, minimum, maximum, and Cronbach alpha values. The LHB-17 had a Cronbach alpha of 0.71, suggesting acceptable internal consistency. The overall mean for the LHB-17 scale is -6.27 ± 7.61, indicating a trend towards increased unhealthy LHBs, particularly diet (− 2.28 ± 5.87), sleep (− 2.01 ± 1.34), and psychological (− 2.80 ± 2.15) scores. However, the physical activity score showed a slight increase in healthy physical activities (0.82 ± 2.83) among participants during the COVID-19 pandemic. Furthermore, 63.9% of the study participants had a WHO-5-A score below 13 and thus fell into the category of poor mental well-being. The FCV-19S results indicate that 55.9% of the participants had a high fear of COVID-19 (scores between 21 and 35), while 44.7% had a low fear (scores between 1 and 20).

3.3 Bivariate analysis

Female participants had significantly unhealthier behaviors than males (mean (m) female = − 7.33 vs. m male =− 5.14; p = 0.004). Lower LHB-17 scores were significantly associated with the following sociodemographic features: being a Lebanese permanent resident (m resident = − 6.66 vs. m visitor = 0.42; p < 0.001), living in Beirut (m = − 9.06), Beqaa (m = − 8.14), and North (m = − 8.00) (p < 0.001), living in a rural region (m rural = − 7.18 vs. m urban = -4.25; p < 0.001), school education level (m school = − 8.73 vs. m university =− 5.83; p < 0.001), being Muslim (m = − 7.09) or Christian (m = − 6.76) vs. atheist (m = 0.98; p < 0.001), no family income (m = -8.45; p = 0.003), being very worried not to meet the monthly living expenses (m = − 9.29; p < 0.001), being unemployed (m =− 7.56; p < 0.001), working in the military vs. the private sector (m military = − 10.57 vs. m private = − 5.51; p = 0.007), smoking cigarettes (m = − 6.84; p = 0.007), and having a poor overall health (m = − 16.21; p < 0.001).

Furthermore, lower LHB-17 scores were also significantly associated with the following variables during the COVID-19 pandemic: a higher number of hours spent using electronic devices during the lockdown (r =− 0.15; p = 0.002), a higher BMI (r = − 0.11; p = 0.027), increased weight (m = − 10.34; p < 0.001), slightly increased smoking (m = − 9.95; p < 0.001), significantly increased alcohol consumption (m = − 14.73; p < 0.001), having a family member infected with coronavirus (m = − 7.27; p < 0.001), and greater fear of COVID-19 (r = − 0.123; p = 0.014). However, higher well-being (WHO-5-A) scores were associated with higher LHB-17 scores (r = 0.16; p = 0.001).

The mean number of hours per day spent using electronic devices significantly increased from (m ± SD) 5.33 ± 4.13 before the lockdown to 7.88 ± 4.48 during the lockdown (p < 0.001). Also, participants who reported negative changes in physical health during the confinement were those who significantly increased their intake of nutrition supplements (72.3%) and immunity-boosting foods (77.9%) (p < 0.001).

Tables 2 and 3 present the detailed results of the bivariate analyses, taking the LHB-17 scale as the dependent variable.

3.4 Multivariable analysis

The nested model analysis, taking the LHB-17 scale as the dependent variable, revealed several significant associations in each of the three models (Table 4).

The first model included the sociodemographic variables and showed that living in an urban region (unstandardized beta (ß) = 3.653) and currently working (ß = 2.060) were significantly associated with higher LHB-17 scores. Whereas being a female (ß = − 2.336), living in Beirut, Beqaa, and North Lebanon (ß = − 0.853), being a Lebanese permanent resident (ß = − 7.676), and currently worrying about the financial situation (ß = − 0.775) were significantly associated with lower LHB-17 scores among participants.

The second model, which included sociodemographic and general health-related behavior variables, showed that living in an urban region (ß = 3.025), currently working (ß = 1.920), having good overall health (ß = 3.510), and having a higher quality of life (ß = 0.288) were significantly associated with higher LHB-17 scores. However, being a female (ß = − 2.019), living in Beirut, Beqaa, and North Lebanon (ß = − 0.919), being a Lebanese permanent resident (ß = − 7.094), smoking nargileh (ß = − 3.137), and having a higher BMI (ß = − 0.263) were significantly associated with lower LHB-17 scores.

The third model, consisting of sociodemographic, general health-related behaviors, and COVID-19-related variables, showed that living in an urban region (ß = 2.464), having good overall health (ß = 3.543), a higher quality of life (ß = 0.204), and having physical (ß = 2.101) and mental (ß = 1.586) health affected by the COVID-19 lockdown were significantly associated with higher LHB-17 scores. However, living in Beirut, Beqaa, and North Lebanon (ß = − 1.213), being a Lebanese permanent resident (ß = − 7.502), smoking nargileh (ß = − 3.433), gaining weight (ß = − 0.853), and spending more hours per day using electronic devices (ß = − 0.164) during the COVID-19 lockdown were significantly associated with lower LHB-17 scores.

4 Discussion

The COVID-19 pandemic had a significant public health impact with severe global economic and social consequences. Thus, this study aimed to evaluate the reported changes in various lifestyle habits during the COVID-19 pandemic among a sample of Lebanese adults.

Our results revealed that the COVID-19 pandemic, particularly the lockdown period, has profoundly affected LHBs, highlighting unfavorable lifestyle changes in dietary habits, physical activity (length and type), sleep (duration and quality), and psychological health (irritability, stress, and anxiety).

Several sociodemographic factors, including gender, were associated with perceived changes in lifestyle and behaviors. Expectedly, women exhibited significantly lower LHB-17 scores than men; women and men might not equally experience the negative repercussions of long lockdown periods, fear of infection, frustration, boredom, financial loss, and stigma related to the COVID-19 pandemic. Previous work has demonstrated that Lebanese women had higher stress, anxiety, and post-traumatic stress symptoms than men [40]. As families were confined at home, women’s domestic chore workload considerably increased, which could have consumed them physically. They had to assume their children’s homeschooling and secure a “state of tranquility” for learning children or partners, working remotely from home, at least during the total lockdown [41,42,43,44]. Thus, the lack of energy and time would reduce their ability to improve their habits and behaviors.

Other sociodemographic factors, i.e., being a Lebanese permanent resident and worrying about the economic situation, were associated with unfavorable lifestyle changes, whereas having a job and living in an urban region were significantly associated with positive changes. Such results can be explained by the economic hardship that adds to the sanitary crisis in Lebanon. Indeed, Lebanon is witnessing an unprecedented economic crisis and was recently downgraded from a high-income to an upper-middle-income country by the World Bank [45]. This critical financial situation was exacerbated by the inability to control the exchange rate of the US dollar against the Lebanese pound, which dramatically skyrocketed in less than a year, leading to massive demonstrations, strikes, and temporary bank closures [46, 47]. Hence, Lebanese residents, particularly the unemployed or those worrying about their financial situation, could not introduce good practices and afford healthy products; instead, they exhibit a limited and weakened motivation to change habits positively and embrace a healthy lifestyle.

As for the general health-related factors, an increased BMI and weight gain during COVID-19 were significantly associated with lower LHB-17 scores. Almost one-third of our sample reported weight gain, in agreement with previous findings showing that 31% of 1012 subjects reported weight gain since lockdown due to COVID-19 began in the United Arab Emirates [30]. Several other studies, including Lebanese ones, demonstrated weight gain during the COVID-19 home confinement [2, 25, 48,49,50], likely due to boredom, anxiety, and stress reactions to COVID-19 leading to changes in eating habits, such as increased consumption of highly energetic foods (rich in sugar and fat) [51].

Our results revealed increased smoking among participants. Studies on changes in tobacco use during the pandemic have yielded controversial results [22, 52, 53]. Indeed, some studies have reported increased tobacco use [54], while others have recorded decreased smoking [52]. Smokers usually intensify their consumption to cope with pandemics, given their detrimental effects on mental health [55].

When exploring COVID-19-related factors, most participants reported a longer screen time, in line with previous findings [56,57,58,59], showing a 65–70% increase in screen time during the COVID-19 pandemic [56, 58]. This increase is explained by the imposed lockdown, where most people had to work or study from home and thus were more likely to spend long screen periods reading, homeschooling, playing, meeting, or watching movies [59]. In our study, participants who reported spending more time per day using electronic devices during the COVID-19 lockdown had significantly lower LHB-17 scores. A report published by the WHO pointed out that young people, as in our study, might be particularly vulnerable to the harms of excessive screen time, including misinformation about COVID-19, cyberbullying, gaming disorders, and unhealthy sedentary lifestyles [60]. Previous studies have also reported these changes in dietary habits and lifestyle behaviors during the pandemic [9, 30, 50, 61, 62].

Surprisingly, in addition to the longer screen time reported during the COVID-19 pandemic, our results also revealed a slight increase in leisure time and healthy physical activities. Moreover, participants who already had better well-being and overall health and those who did not report changes in their physical and mental health during COVID-19 had higher LHB-17 scores and thus tended to report positive lifestyle changes. Similarly, a study among 1807 participants from the Middle East and North Africa (MENA) region described increased physical activity, better health status, and higher mental well-being scores [63]. However, a recent meta-analysis of 66 studies found opposite results, reflected by decreased physical activity and increased sedentary behaviors during the COVID-19 pandemic [64]. One explanation could be that during the data collection period, the Lebanese government had not imposed strict mobility restrictions, and most of the young participants could escape the vigilance of authorities to go out and continue their daily outdoor sports activities.

Our results revealed that participants who reported having physical and mental health affected by the lockdown had lower LHB-17 scores, consistent with the findings of a study among Lebanese adults showing that the fear of COVID-19 coupled with economic hardship was associated with higher stress and anxiety [26]. This psychological distress could considerably affect health behaviors, as previously described [65, 66]. Most studies have demonstrated that higher levels of depression, anxiety, and stress are significantly associated with unfavorable changes in physical activity, sleep, smoking, and alcohol consumption [65]. Health promotion strategies should be implemented to assess negative changes in physical or mental health and maintain as many positive health-related behaviors as possible, particularly in young populations [60].

4.1 Limitations and strength

Our study has several limitations related to its cross-sectional design and data collection process. Even though our sample was weighted to adjust for the over- or under-representation of gender and governorate distribution, our population consisted mainly of young people with a university level of education, thus expected to have high computer literacy and internet access. Therefore, our results might not be generalized to the whole population. Moreover, a possible information bias could be likely since the questionnaire was self-administered, with no possibility of clarifying confusing questions.

However, despite these limitations, to the best of our knowledge, this study is the first to evaluate the effect of sociodemographic features, general health-related behaviors, and COVID-19-related factors on lifestyle changes among the general Lebanese population, almost a year after the COVID-19 outbreak. Furthermore, the use of a standardized questionnaire with validated scales with acceptable to excellent reliability is likely to reduce possible information bias.

5 Conclusions

Lebanese adults reported several unfavorable lifestyle changes and psychological problems during the lockdown due to COVID-19. Notably, unfavorable lifestyle changes in dietary habits, sleep (duration and quality), and psychological health (irritability, stress, and anxiety) were reported, particularly affecting women, non-workers, waterpipe smokers, electronic device heavy users, people of lower socioeconomic status, and those with chronic diseases. Health promotion strategies are needed to assess negative changes both in physical and mental health and maintain as many positive health-related behaviors as possible among the Lebanese population, particularly during rough times such as disease outbreaks, wars, and economic crises.

Data availability

The datasets generated during and/or analyzed during the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

Abbreviations

- COVID-19:

-

Coronavirus disease 2019

- LHBs:

-

Lifestyle and health-related behaviors

- LHB-17:

-

Lifestyle and Health Behaviors scale

- FCV-19S:

-

Fear of COVID-19 scale

- LBP:

-

Lebanese pound

- WHO:

-

World Health Organization

- BMI:

-

Body Mass Index

- SPSS:

-

Statistical package for social sciences

- m:

-

Mean

- SD:

-

Standard deviations

- ß:

-

Unstandardized beta

- MENA:

-

Middle East and North Africa

References

Coronavirus disease (COVID-19) pandemic. https://www.who.int/emergencies/diseases/novel-coronavirus-2019.

Di Renzo L, Gualtieri P, Pivari F, Soldati L, Attina A, Cinelli G, Leggeri C, Caparello G, Barrea L, Scerbo F, et al. Eating habits and lifestyle changes during COVID-19 lockdown: an Italian survey. J Transl Med. 2020;18(1):229.

Coronavirus disease (COVID-19): Health and safety in the workplace https://www.who.int/news-room/q-a-detail/coronavirus-disease-covid-19-health-and-safety-in-the-workplace.

Lotfinejad N, Peters A, Pittet D. Hand hygiene and the novel coronavirus pandemic: the role of healthcare workers. J Hosp Infect. 2020;105(4):776–7.

Scarmozzino F, Visioli F. Covid-19 and the Subsequent Lockdown Modified Dietary Habits of Almost Half the Population in an Italian Sample. Foods. 2020;9(5):675.

Meyer J, McDowell C, Lansing J, Brower C, Smith L, Tully M, Herring M. Changes in physical activity and sedentary behavior in response to covid-19 and their associations with mental health in 3052 US adults. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2020;17(18):6469.

Guan H, Okely AD, Aguilar-Farias N, Del Pozo CB, Draper CE, El Hamdouchi A, Florindo AA, Jauregui A, Katzmarzyk PT, Kontsevaya A, et al. Promoting healthy movement behaviours among children during the COVID-19 pandemic. Lancet Child Adolesc Health. 2020;4(6):416–8.

Ammar A, Mueller P, Trabelsi K, Chtourou H, Boukhris O, Masmoudi L, Bouaziz B, Brach M, Schmicker M, Bentlage E, et al. Psychological consequences of COVID-19 home confinement: the ECLB-COVID19 multicenter study. PLoS ONE. 2020;15(11): e0240204.

Ammar A, Brach M, Trabelsi K, Chtourou H, Boukhris O, Masmoudi L, Bouaziz B, Bentlage E, How D, Ahmed M et al: Effects of COVID-19 Home Confinement on Eating Behaviour and Physical Activity: Results of the ECLB-COVID19 International Online Survey. Nutrients 2020, 12(6).

Brooks SK, Webster RK, Smith LE, Woodland L, Wessely S, Greenberg N, Rubin GJ. The psychological impact of quarantine and how to reduce it: rapid review of the evidence. Lancet. 2020;395(10227):912–20.

Emotional consequences of COVID-19 home confinement: The ECLB-COVID19 multicenter study [https://www.medrxiv.org/content/https://doi.org/10.1101/2020.05.05.20091058v1?__cf_chl_captcha_tk__=deb2a8d82069111b49a861d5e32239a0ccbb3a08-1615924128-0-AeN8Pd6ClyV70AWJcdjIqMe7ZdOxScuNn2p12IA9vGTRrHhrOdnIxKfqB9xZVl4f1YbFQz8buaAGmoMWMDbgp-1ty9_OpdmLSDWelhq_8-fFu0gD3shNM6vdzNfMROTsH-_93nMLF0kyMo0LMsHh1sRk9gbHe0BIfrPrHT7FeYoBAs63-G4f3_pSlcU0AnKW3oCuyWbpZzYJdKYkLPVOtyeKJkQT8qtS7jv3h7ElJyvNyGEp9mOt9ewsRsBU1gMr0XGrThX1kUgnNzhJiU239USFmVmWvzAoYcpoyMUR2cSBIymHLghMopLQU1UdnL769GOa_k8-gQFGDFE_ZzSXqpqQXiuJ2YV7GzxiWeBKQVfjSo-NLkoQh43OmZIMiVIEVWJ-oZb_I0j4B48jAGd3md76HsnCYU6hSPzyYOofvMdHPUJVq4zU6Yb7kI02obtU4dw6QP9549obZxQw7T-NeevfRU-yLqUj3-xVUnhABfA0fWE2-2Stbif4Ca8jiv8fhzMExn9xkCbAddGDyAF10OICdnabLeGOCn4cBRK5qOnqm-4NDfwzyDff5-t817En08C-dRgwjQ_96eGtZMqJY74]

Volino-Souza M, de Oliveira GV, Conte-Junior CA, Alvares TS. Covid-19 quarantine: impact of lifestyle behaviors changes on endothelial function and possible protective effect of beetroot juice. Front Nutr. 2020;7: 582210.

Flanagan EW, Beyl RA, Fearnbach SN, Altazan AD, Martin CK, Redman LM. The impact of COVID-19 stay-at-home orders on health behaviors in adults. Obesity (Silver Spring). 2021;29(2):438–45.

‘I Just Need the Comfort’: Processed Foods Make a Pandemic Comeback. https://www.nytimes.com/2020/04/07/business/coronavirus-processed-foods.html

Wang C, Pan R, Wan X, Tan Y, Xu L, Ho CS, Ho RC. Immediate psychological responses and associated factors during the initial stage of the 2019 coronavirus disease (COVID-19) epidemic among the general population in China. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2020;17(5):1729.

Montemurro N. The emotional impact of COVID-19: from medical staff to common people. Brain Behav Immun. 2020;87:23–4.

Simons D, Shahab L, Brown J, Perski O: The association of smoking status with SARS-CoV-2 infection, hospitalization and mortality from COVID-19: a living rapid evidence review with Bayesian meta-analyses (version 7). Addiction 2020.

Engin AB, Engin ED, Engin A. Two important controversial risk factors in SARS-CoV-2 infection: obesity and smoking. Environ Toxicol Pharmacol. 2020;78: 103411.

Edwards R, Munafo M. COVID-19 and tobacco: more questions than answers. Nicotine Tob Res. 2020;22(9):1644–5.

Bommele J, Hopman P, Walters BH, Geboers C, Croes E, Fong GT, Quah ACK, Willemsen M. The double-edged relationship between COVID-19 stress and smoking: Implications for smoking cessation. Tob Induc Dis. 2020;18:63.

Tattan-Birch H, Perski O, Jackson S, Shahab L, West R, Brown J: COVID-19, smoking, vaping and quitting: a representative population survey in England. Addiction 2020.

Kowitt SD, Cornacchione Ross J, Jarman KL, Kistler CE, Lazard AJ, Ranney LM, Sheeran P, Thrasher JF, Goldstein AO. Tobacco quit intentions and behaviors among cigar smokers in the United States in response to COVID-19. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2020;17(15):5368.

Coronavirus Disease 2019 (COVID-2019) National Health Strategic Preparedness and Response Plan. https://www.moph.gov.lb/en/Media/view/27426/coronavirus-disease-health-strategic-preparedness-and-response-plan.

Akel M, Berro J, Rahme C, Haddad C, Obeid S, Hallit S. Violence against women during COVID-19 pandemic. J Interpers Violence. 2021. https://doi.org/10.1177/0886260521997953.

Haddad C, Zakhour M, Siddik G, Haddad R, Sacre H, Salameh P: Coronavirus disease 2019 outbreak: Does confinement have any impact on weight variation and weight change perception? Nutrition Clinique et Métabolisme 2021, Accepted, Under Press.

Salameh P, Hajj A, Badro DA, Abou Selwan C, Aoun R, Sacre H. Mental health outcomes of the COVID-19 pandemic and a collapsing economy: perspectives from a developing country. Psychiatry Res. 2020;294: 113520.

El Othman R, Touma E, El Othman R, Haddad C, Hallit R, Obeid S, Salameh P, Hallit S. COVID-19 pandemic and mental health in Lebanon: a cross-sectional study. Int J Psychiatry Clin Pract. 2021. https://doi.org/10.1080/13651501.2021.1879159.

Epi info 7. https://www.cdc.gov/epiinfo/index.html

CheikhIsmail L, Osaili TM, Mohamad MN, AlMarzouqi A, Jarrar AH, Zampelas A, Habib-Mourad C, OmarAbuJamous D, Ali HI, AlSabbah H, et al. Assessment of eating habits and lifestyle during the coronavirus 2019 pandemic in the Middle East and North Africa region: a cross-sectional study. Br J Nutr. 2020. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0007114520004547.

Kumari A, Ranjan P, Vikram NK, Kaur D, Sahu A, Dwivedi SN, Baitha U, Goel A. A short questionnaire to assess changes in lifestyle-related behaviour during COVID 19 pandemic. Diabetes Metab Syndr. 2020;14(6):1697–701.

Topp CW, Ostergaard SD, Sondergaard S, Bech P. The WHO-5 Well-Being Index: a systematic review of the literature. Psychother Psychosom. 2015;84(3):167–76.

Wellbeing Measures in Primary Health Care/The Depcare Project. WHO Regional Office for Europe: Copenhagen. https://www.euro.who.int/__data/assets/pdf_file/0016/130750/E60246.pdf.

Sibai AM, Chaaya M, Tohme RA, Mahfoud Z, Al-Amin H. Validation of the Arabic version of the 5-item WHO Well Being Index in elderly population. Int J Geriatr Psychiatry. 2009;24(1):106–7.

Ahorsu DK, Lin C-Y, Imani V, Saffari M, Griffiths MD, Pakpour AH: The fear of COVID-19 scale: development and initial validation. Int J Mental Health Addict 2020:1–9.

Alyami M, Henning M, Krägeloh CU, Alyami H: Psychometric evaluation of the Arabic version of the Fear of COVID-19 Scale. Int J Mental Health Addict 2020:1–14.

Demographic and Social Statistics http://cas.gov.lb/index.php/demographic-and-social-en.

Taber KS. The use of Cronbach’s alpha when developing and reporting research instruments in science education. Res Sci Educ. 2018;48:1273–96.

Chowdhury MZI, Turin TC. Variable selection strategies and its importance in clinical prediction modelling. Fam Med Community Health. 2020;8(1): e000262.

Sacre H, Hajj A, Badro DA, Abou Selwan C, Aoun R, Salameh P: Health Outcomes based on Gender and Domestic Violence in a context of the COVID-19 Pandemic and a Collapsing Economy. Submitted article 2021.

Wenham C, Smith J, Morgan R. Gender, Group C-W: COVID-19: the gendered impacts of the outbreak. Lancet. 2020;395(10227):846–8.

UNESCO explores “Online Teaching and Learning” during the Lebanese Internet Governance Forum. https://en.unesco.org/news/unesco-explores-online-teaching-and-learning-during-lebanese-internet-governance-forum.

COVID19: Is Lebanon Ready for Online Higher Education? https://www.aub.edu.lb/ifi/news/Pages/20200330-covid19-is-lebanon-ready-for-online-higher-education.aspx.

Lebanon’s experience with distance learning. https://www.executive-magazine.com/economics-policy/lebanons-experience-with-distance-learning.

Arezki R, Mottaghi L, Barone A, Fan RY, Harb AA, Karasapan OM, Matsunaga H, Nguyen H, de Soyres F: A New Economy in Middle East and North Africa. In: Middle East and North Africa Economic Monitor. Washington, DC: World Bank © 2018.

Lebanon economic monitor: so when gravity beckons, the poor don’t fall. In: Global Practice for Macroeconomics, Trade & Investment, Middle East and North Africa Region. [http://documents.worldbank.org/curated/en/349901579899850508/pdf/Lebanon-Economic-Monitor-So-When-Gravity-Beckons-the-Poor-Dont-Fall.pdf. Accessed 22 May 2020.

Khraiche, D. Lebanon's Banks Set Limits They Won't Call Capital Controls. [https://www.bloomberg.com/news/articles/2019-11-17/lebanese-banks-to-impose-first-joint-measures-in-face-of-crisis. Accessed 25 May 2020.

Bhutani S, Cooper JA. COVID-19-related home confinement in adults: weight gain risks and opportunities. Obesity (Silver Spring). 2020;28(9):1576–7.

Deschasaux-Tanguy M, Druesne-Pecollo N, Esseddik Y, de Edelenyi FS, Alles B, Andreeva VA, Baudry J, Charreire H, Deschamps V, et al. Diet and physical activity during the coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) lockdown (March-May 2020): results from the French NutriNet-Sante cohort study. Am J Clin Nutr. 2019. https://doi.org/10.1093/eurpub/ckab165.063.

Husain W, Ashkanani F. Does COVID-19 change dietary habits and lifestyle behaviours in Kuwait: a community-based cross-sectional study. Environ Health Prev Med. 2020;25(1):61.

Moynihan AB, van Tilburg WA, Igou ER, Wisman A, Donnelly AE, Mulcaire JB. Eaten up by boredom: consuming food to escape awareness of the bored self. Front Psychol. 2015;6:369.

Caponnetto P, Inguscio L, Saitta C, Maglia M, Benfatto F, Polosa R. Smoking behavior and psychological dynamics during COVID-19 social distancing and stay-at-home policies: a survey. Health Psychol Res. 2020;8(1):9124.

Patwardhan P. COVID-19: Risk of increase in smoking rates among England’s 6 million smokers and relapse among England’s 11 million ex-smokers. BJGP Open. 2020. https://doi.org/10.3399/bjgpopen20X101067.

Tzu-Hsuan Chen D. The psychosocial impact of the COVID-19 pandemic on changes in smoking behavior: Evidence from a nationwide survey in the UK. Tob Prev Cessat. 2020;6:59.

Lawless MH, Harrison KA, Grandits GA, Eberly LE, Allen SS. Perceived stress and smoking-related behaviors and symptomatology in male and female smokers. Addict Behav. 2015;51:80–3.

Hu Z, Lin X, Chiwanda Kaminga A, Xu H. Impact of the COVID-19 epidemic on lifestyle behaviors and their association with subjective well-being among the general population in Mainland China: cross-sectional study. J Med Internet Res. 2020;22(8): e21176.

Majumdar P, Biswas A, Sahu S. COVID-19 pandemic and lockdown: cause of sleep disruption, depression, somatic pain, and increased screen exposure of office workers and students of India. Chronobiol Int. 2020;37(8):1191–200.

Pisot S, Milovanovic I, Simunic B, Gentile A, Bosnar K, Prot F, Bianco A, Lo Coco G, Bartoluci S, Katovic D, et al. Maintaining everyday life praxis in the time of COVID-19 pandemic measures (ELP-COVID-19 survey). Eur J Public Health. 2020;30(6):1181–6.

igital screen time during the COVID-19 pandemic: a public health concern. https://f1000research.com/articles/10-81.

Excessive screen use and gaming considerations during #COVID19. http://www.emro.who.int/mnh/news/considerations-for-young-people-on-excessive-screen-use-during-covid19.html.

Pellegrini M, Ponzo V, Rosato R, Scumaci E, Goitre I, Benso A, Belcastro S, Crespi C, De Michieli F, Ghigo E, et al. Changes in weight and nutritional habits in adults with obesity during the “Lockdown” period caused by the COVID-19 virus emergency. Nutrients. 2020;12(7):2016.

Chopra S, Ranjan P, Singh V, Kumar S, Arora M, Hasan MS, Kasiraj R, Suryansh, Kaur D, Vikram NK et al: Impact of COVID-19 on lifestyle-related behaviours- a cross-sectional audit of responses from nine hundred and ninety-five participants from India. Diabetes Metab Syndr 2020, 14(6):2021–2030.

Kilani HA, Bataineh MF, Al-Nawayseh A, Atiyat K, Obeid O, Abu-Hilal MM, Mansi T, Al-Kilani M, Al-Kitani M, El-Saleh M, et al. Healthy lifestyle behaviors are major predictors of mental wellbeing during COVID-19 pandemic confinement: a study on adult Arabs in higher educational institutions. PLoS ONE. 2020;15(12): e0243524.

Stockwell S, Trott M, Tully M, Shin J, Barnett Y, Butler L, McDermott D, Schuch F, Smith L. Changes in physical activity and sedentary behaviours from before to during the COVID-19 pandemic lockdown: a systematic review. BMJ Open Sport Exerc Med. 2021. https://doi.org/10.1136/bmjsem-2020-000960.

Stanton R, To QG, Khalesi S, Williams SL, Alley SJ, Thwaite TL, Fenning AS, Vandelanotte C. Depression, anxiety and stress during COVID-19: associations with changes in physical activity, sleep, tobacco and alcohol use in australian adults. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2020;17(11):4065.

Garre-Olmo J, Turro-Garriga O, Marti-Lluch R, Zacarias-Pons L, Alves-Cabratosa L, Serrano-Sarbosa D, Vilalta-Franch J, Ramos R. Girona healthy region study G: changes in lifestyle resulting from confinement due to COVID-19 and depressive symptomatology: a cross-sectional a population-based study. Compr Psychiatry. 2021;104: 152214.

Acknowledgements

The authors would like to thank all colleagues who helped in disseminating the questionnaire and all participants who filled it and shared it with their contacts.

Funding

No funding was received for conducting this study.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

DS, PS Conceptualization; DS, HS Data curation; DS, PS Formal analysis; DS, AH, DM, HS, CH, PS Investigation; DS, PS Methodology; DS, PS, DM Project administration; DS, PS, AH, HS Resources, PS Supervision; DS, HS Visualization; DS, AH, DM, CH Writing – original draft preparation; HS, DS, AH, DM, HS, CH, PS Writing – review & editing.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate

This study was conducted according to the guidelines laid down in the Declaration of Helsinki, and the study protocol was approved by the Lebanese International University (LIU) ethics committee (2020RC-034-LIUSOP). Electronic informed consent was obtained from all participants on the first page of the questionnaire.

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/. The Creative Commons Public Domain Dedication waiver (http://creativecommons.org/publicdomain/zero/1.0/) applies to the data made available in this article, unless otherwise stated in a credit line to the data.

About this article

Cite this article

Saadeh, D., Hajj, A., Malaeb, D. et al. Assessment of lifestyle and health-related behaviors and correlates during the COVID-19 pandemic among Lebanese adults. Discov Public Health 21, 24 (2024). https://doi.org/10.1186/s12982-024-00142-9

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/s12982-024-00142-9