Abstract

Background

Tobacco dependence is a chronic disease that often requires repeated interventions and multiple attempts to quit. Cigarette smoking is the leading preventable cause of mortality. Globally, an estimated 1.3 billion people smoke.

In Qatar, Smoking cessation services (SCSs) are provided free of charge to citizens and at a minimal cost to non-citizens. This study aimed to measure the effectiveness of the smoking cessation program adopted by the Primary Health Care Corporation (PHCC) of Qatar. This was achieved through calculating the percentage of smoking cessation service users (survival probabilities) who maintained the non-smoking status after selected follow up periods. Moreover, the study highlighted the possible association of selected explanatory variables with smoking cessation survival probabilities.

Methods

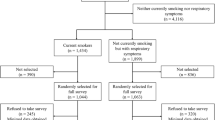

In this historical cohort study 490 participants were recruited by simple random sampling who attended the smoking cessation clinics (SCCs) in PHCC prior to 30/06/2021. The participants were contacted by phone and invited to participate in the study. The participants who agreed to participate in the study were interviewed utilizing a structured questionnaire.

Results

Initially 311 (63.5%) of the participants quitted smoking after receiving SCSs. There were statistically significant differences between quitting smoking and the nationality and the educational level of participants (p ≤ 0.001 and 0.02 respectively). About one fourth (23.3%) of individuals who initially quitted smoking relapsed and resumed smoking as early as 6 months after completing their SCC visits. This relapse rate increased to 38.7, 47.2 and 51.1% after 12, 24 and 36 months respectively. Less than a half (45.8%) maintained the non-smoking status after 42 months from their initially quitting.

Conclusion and recommendations

The findings of the study substantiate the effectiveness of SCSs designed within PHCC both in short- and long-term basis. Younger individuals, smokers with Arab ethnicity, smokers falling within high income and education groups were identified as high-risk groups and need highest focus. The accessibility to the service among the local population can be increased by upscaling the advertisement of the existing services.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

1 Introduction

Globally, smoking and its associated health implications has been a major public health concern over the decades [1,2,3]. Accordingly, to the World Health Organization (WHO) there are 1.3 billion tobacco consumers worldwide which causes 8 million deaths annually [4]. Evidence suggests that smoking contributes to a myriad of preventable diseases and premature deaths [3]. Smoking rates estimated to be as high as 50 percent for men in developing countries and mostly concentrated among those of low socioeconomic status [5, 6].

Cigarettes are the most common smoking item consumed in the various geographical settings compared to the other tobacco products [4].

There have been various interventions and preventive strategies that have been implemented in various settings through smoking cessation services [7, 8]. These interventions mainly constitute therapeutic and behavioral interventions [7, 9]. The framework convention on tobacco control (FCTC) was launched under the auspices of WHO as an international coordinated response to tackle the tobacco epidemic [10]. The various strategies advocated by the initiative included implementing tax measures to restrict tobacco consumption, promoting smoke-free environment at work and public places, restricting and banning all types of marketing of smoking products and strengthening legislative measures to prevent illicit trade of tobacco products [11]. Despite these global initiatives, a significant portion of the population continue to smoke globally [12].

It is extensively discussed in literature that there are different factors contributing to smoking initiation such as and not limited to attitudes and beliefs, nicotine dependence, availability of flavored tobacco products, use of e-cigarettes, previous experience with smoking even few puffs, depression, poor school performance and substance abuse [13,14,15,16,17,18]. In addition, there are various factors linked with smoking behaviors, accessibility of smoking cessation services and compliance to the various cessation interventions. These mainly include socio-demographic characteristics of smokers, cultural issues, economic status, ethnicity and age [3].

Clinician involvement increases the likelihood of smoking cessation. The goal of smoking cessation establishment is to offer evidence-based services [19]. Tobacco dependence interventions, if delivered in a timely and effective manner, significantly decrease the risk of smoking-related morbidity and mortality [20, 21]. The clinician’s role is to document smoking status, offer advice to quit, evaluate the patient’s interest in quitting. Then, for those interested in quitting, offer tools, techniques, and follow-up. For those not ready to quit, the clinician can use motivational interviewing to move the smoker towards quitting. [22,23,24,25].

Qatar has well-developed and modernized healthcare system with comprehensive primary health care services which provide specialized evidence-based smoking cessation services. These services usually provided through different initial and follow up visits. Despite these healthcare resources smoking remains a major public health concern [26]. Whereas the overall prevalence of smoking was 16.4% among the studied population in the STEP wise survey, and the percentage of smoking among men was almost 27 folds higher than that among women (31.9 vs. 1.2%) [27].

To reduce inappropriate variation in smoking cessation support practice and to promote efficient use of resources, PHCC developed a smoking cessation guideline aimed to describe appropriate care based on the best available scientific evidence and broad consensus for smoking cessation practice [28]. According to that guideline the provided care mainly formed of assessing services such as assessing carbon monoxide level and assessing nicotine dependence using Fagerstrom Test for Nicotine Dependence. In addition to the assessing tests the clinician’s services mainly formed of general/behavioral counseling according to each case separately and pharmacotherapy (see appendix 1). Since SCSs are already in place within the PHCC, this study may cover the current situation and discover any gaps and deficiencies that may be presented within the services provided.

The main aim of the study is to investigate the demographic profile, attributes and the incidence of smoking cessation among individuals receiving smoking cessation services in primary care settings of Qatar, as well as assessing the rate of relapse for those who initially quitted smoking after attending the SCCs. The findings of the study may inform policymakers and public health authorities in Qatar to develop evidence-based tobacco control policies.

2 Methods

2.1 Study design

This is a historical cohort study implemented on a primary care level.

2.2 Study population

Smokers were recruited in the study who were accessing smoking cessation clinics and were registered at primary health care centers in Qatar on June 30th, 2021. Smokers who did not complete 42 months of follow-up since quitting smoking were excluded from the study.

2.3 Sample size calculation

The non-parametric exponential model for survival analysis used to calculate the required sample size for performing survival analysis on persons who reported quitting smoking during their enrollment period for smoking cessation program [29]. The model was fed with the following parameters:

-

Length of accrual period = 42 months

-

T, the length of follow-up period-time from end of accrual to analysis = 6 months

-

α, the significance level = (0.05)

-

Two-sided test

-

Estimated Survival probability at time t = 12 months = 0.5

-

Upper and lower critical values for the estimated survival probability = 0.05 (95% confidence interval of 1-year survival rate of 0.45 to 0.55)

The sample size required for performing the required survival analysis under the above model parameters was 330. Under the assumption of 50% rate for quitting smoking during the smoking cessation program visits we needed to double the required sample size to 660 to end with the required 330 who quitted smoking. In addition, we added another 130 participants to the required sample size to account for an expected 20% non-response rate. The final sample size became 790.

2.4 Data collection

A simple random sample of 790 participants were extracted from the PHCC electronic registry of all attendees to the SCCs until 31/6/2021 to take part in this study. That was after exclusion of those who did not complete 42 months of follow-up on that date. Of those participants, only 490 have gave their verbal consents to participate in the study. Data were collected by well-trained data collectors through phone interviews with the participants used a structured questionnaire form. Prior to data collection, the questionnaire was piloted amongst 20 selected past users of SCC and their feedbacks were used to make any necessary amendments.

2.5 The study tool

The structured questionnaire has developed by the researchers, the content and face validity have established by an extensive literature review, consultation of the community medicine faculty and experts in the field of smoking cessation [5, 30,31,32,33,34,35,36,37,38,39,40,41,42,43,44,45,46,47,48,49,50,51,52,53,54,55,56,57,58,59,60,61,62,63,64,65,66,67,68,69,70,71,72,73,74,75,76,77,78,79,80,81,82,83]. The questionnaire has originally prepared in English and translated into Arabic language with back translation to ensure its validity. The translation done by the lead researcher using several medical dictionaries and then was revalidated again by two Community Medicine Experts after reverse translation. After conducting an extensive literature, the aim and objectives of the study served as a guide for the researcher in developing the content of the questionnaire.

The final version of the questionnaire covered several areas which were the history of visits to SCCs with their initial outcome, the sociodemographic characteristics of participants, impact of smoking cessation on health status and the socio-economic status of participants, as well as the withdrawal symptoms of smoking cessation.

The component of the study tool which includes multiple choice questions, some of the patients may have more than eligible choices or responses. The interaction between the different choices or responses can influence the reported percentage of the overall response rates, for example the reasons for visiting SCC. A copy of the questionnaire added as a supplementary file.

2.6 Data analysis

Statistical analysis was done using IBM SPSS Statistics software version 28. Descriptive statistics were done first. The association between selected explanatory variables (age, gender, nationality, income, marital status, and educational level) and mean survival time for keeping the non-smoker status was tested for statistical significance by Kaplan Myer test in bivariate model.

The effectiveness (success) of the smoking cessation program will be assessed at two levels using incidence rates. The short-term success rate is the incidence rate of quitting smoking during the clinic contact time (primary smoking cessation rate/the percentage of participant quitted smoking directly by attending the SCC). Among those who successfully quitted smoking the long-term success will be calculated using the survival rate (being free from smoking habit relapse) after 1, 6, 12, 24, 36 and 42 months of quitting smoking during clinic visit.

3 Results

A total of 790 individuals were approached to participate in the study. Data was collected from 490 participants with a response rate 62%. The demographic details of the participants are depicted in Table 1. A significant percentage of participants (43%) were within the range 30–39 years of age followed by 40–49 years of age group (28%). Most participants (n = 468) were males and had a smoking history of more than 10 years (90.2%). Majority were cigarette smokers (96.3%) followed by Shisha smoking (19.8%) as demonstrated in Table 1.

As shown in Table 2, more than 85% of participants reported that attending the SCCs was due to their self-decision followed by 18% reported family and relatives’ pressure as a reason. This shows that making the decision to abstain from smoking is usually based on different motives and reasons, but in the end personal decision is the basis.

Table 3 shows that 311 (63.5%) of the study’s participants have quitted smoking during their attending of SCCs and receiving the SCSs. This means that the person quit smoking during the period of his/her visit to the SCC to obtain the service, and this period usually ranges from one day to three months. It also showed that the relation between quitting of smoking with the nationality and the educational level of participants was statistically significant. Qataris had a significantly lower quit rate than the other two nationality groups. A lower educational level was associated with a significantly higher quit rate.

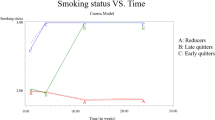

As shown in Table 4, only 2.3% of individuals who initially quitted smoking after SCC visits relapsed and resumed smoking as early as one month after completing their clinic visits. This relapse rate increased to 23.3% after 6 months and 38.7% after 12 months. After 24 months or more of quitting, this rate stabilized at around the level of 50%.

Following the content of Table 4, Fig. 1 is a line graph (survival curve) showing the cumulative incidence rate of maintaining the non-smoking status after selected follow up periods extended to 42 months for those who initially quitted smoking after attending the SCCs at the primary health care centers in Qatar. This graph showed that the median survival for the non-smoking status was 36 months.

As shown in Table 5, all the tested explanatory variables failed to predict significant differences in the risk of smoking relapse for those who initially quitted smoking after getting SCSs. Otherwise, the results showed that the mean survival time (MST) increased visibly with age ≥ 40 years old and showed that there is difference in the mean between Qataris and other Arabs (30.9 vs. 24.4 respectively).

4 Discussion

The SCCs practiced in primary care settings in Qatar are an amalgam of educational, clinical, and social interventions. These services are usually provided by an initial visit as well as several follow up visits according to each case. The different strategies implemented by the clinics in the PHCC constitute of two-tier system. It consists of an initial assessment conducted by nursing staff which is followed by clinician led services which encompasses general/behavioral and pharmacotherapy interventions (see appendix 1). The main findings of the study substantiate the effectiveness of SCSs designed within PHCC both in short- and long-term basis which is substantiated by the fact that less than a half (45.8% which represents 29% of the total participants in the study) maintained the non-smoking status after 42 months from their initially quitting. Moreover, the study highlighted that younger individual, smokers with Arab ethnicity, smokers falling within high income and education groups were identified as high-risk groups and need highest focus.

The main findings of the study signify the fact that the strategies utilized in SCCs of PHCC are effective and can be further upscaled by active engagement of the community.

Recent studies indicate higher smoking trends and patterns among younger age groups particularly among youth [80, 81, 84]. Interestingly, the results of this study highlighted increased smoking rates among middle aged (30–49 years of age) individuals, which eventually decreased among participants older than 60 years of age. The study recruited mostly males with females constituting only 4.5% of the total sample of smokers. Evidence suggests that males have a greater tendency to smoke tobacco [31, 32, 85]. Nevertheless, recent published literature suggests a change in smoking habits with higher incidence among females [33, 34]. The literature suggests that there are higher rates of smoking among ethnic minorities and marginalized populations [81, 86]. A significant percentage of smokers (87%) in this study were non-Qataris and represented the expat population. These findings substantiate the fact that smoking cessation services need to be adapted to meet the needs of these communities [87].

In the present study, more than half of the smokers included in the study had low- or middle-income status. These findings are comparable to studies conducted in the U.S. and China which indicate the association of poverty levels with current smokers [5, 32]. Interestingly the findings of the study revealed a high prevalence of smoking among participants with a substantial educational background. In contrast, the literature suggests that tobacco consumption is more common among populations with low literacy levels and comprising marginalized segments of society as previously discussed [32, 35].

Although there are a significant number of smokeless tobacco users worldwide, cigarette smoking remains the most common route of tobacco consumption, as indicated in this study [82, 83]. Cigarettes are easily available and can be bought at a cheaper price in Qatar than other tobacco products. This might also explain why most smokers (96.3%) consumed this smoking item.

Several studies have emphasized that social support including family and friends has the greatest effect on quit attempts, especially when it is continuing and nondirective as indicated by this study [35, 37, 41]. There are various societal factors that may influence on quitting smoking. Literature highlights various factors namely; partner who dislike smoking or support quitting had a positive influence on quit attempts [38, 79], social avoidance by nonsmokers acts as motivation for smoking cessation [37] and relatives encouragement or illness act as specific reasons for quitting [44]. Smoking cessation is usually mediated by the socioeconomic characteristics of people which affect their habits and decisions [46].

The findings of the study indicated the effectiveness of the smoking cessation services provided within primary care settings in Qatar as nearly two thirds of participants reported initially quitting smoking after receiving the services. One of the key findings of the study was that the rate of successful quitters in the long-term was 29% among the total participants in this study. Similarly, a study assessing the long-term outcome of smoking cessation in outpatient clinic reported a quitting success rate of 20.5% [88]. Evidence suggests that sustained, accountable and comprehensive smoking cessation initiatives can be used to effectively manage tobacco consumption within communities and provide the necessary help for smokers to quit smoking [47,48,49]. Interestingly, the average abstinence rates increase when multimodal interventions (pharmacological and nonpharmacological) are used [43].

Various studies have demonstrated the association between the age of smokers and compliance with smoking cessation services and expected outcomes. Apparently, the findings suggest that the younger the age group is the lower the likelihood of smoking cessation is, whereas compliance with cessation services increases with age [50,51,52]. In this study, smoking cessation was relatively greater among females than among males. The literature suggests that quitting smoking differs between males and females to a certain degree, and many factors such as age, the amount of smoking, and many others may affect this difference [50, 54, 71].

Quit smoking is relatively common among the low-income population as shown in this study and others [47]. Studies contradicting the results of this study showed that smokers with higher incomes or higher social levels were more likely to intend to quit smoking and to abstain for longer durations [55, 89]. However, other studies have found no income differences in quit attempts [62, 64]. Several studies have indicated the clear impact of marital status on smoking status and the decision to quit smoking [56, 67, 68]. This study revealed that smoking cessation initiation was relatively greater among married participants. This may be due to many factors, such as thinking about the health of children or interest in preserving the family’s economic resources. In contrast to our findings, smokers with higher education levels were more likely to intend to quit, to quit, or to abstain for different periods [50, 63]. A study showed that a higher education level was associated with more smoker-related stigma than a lower education level [61]. However, other studies have shown no differences in education level [62, 64].

In this study, the rate of relapse to smoking increased dramatically over time until 24 months after the patient quit smoking. After that, the rate became relatively stable at approximately 50%. These findings are supported by other studies from different countries [62, 63].

The relapse rate is greater among young people than among older people, as indicated in this study and others [57, 72, 73]. One study indicated that age was a significant predictor of smoking cessation [59]. The same study showed that an earlier age at which smoking started was associated with not quitting smoking compared to when people started smoking at an older age [59]. Age did not affect the relapse rate in another study [70].

It is a common assumption that the financial strain has a negative impact on smoking cessation interventions. Contrary to this perception the study findings indicate that the duration of smoking abstinence was inversely related with the level of monthly income. However, evidence indicate that ex-smokers experiencing financial burden are more likely to relapse or having a shorter smoking abstinence [60, 65]. This may be related to the negative impacts of financial strains on the mental and psychological status of people, which in turn may work as a basis for smoking relapse.

The effect of education level on smoking relapse or abstinence duration was relatively limited in the present study. On the other hand, another study indicated that education was a significant predictor of smoking cessation [59]. A longer duration of smoking abstinence was associated with a lower education level in a study from China [73]. A higher education level was associated with greater smoking relapse in another study[72].

5 Limitations of the study

This study helps to develop a better understanding of smoking cessation presented through the SCCs in the primary care settings of Qatar. One of the important advantages of this study was including population from different ethnicities and geographical origins. The study examined multiple outcomes and covariates over different time duration.

One of the limitations of the study are the potential biases that may result in data collection technique and reliance on self-reporting by the participants. The self-reported nature of the data introduces the possibility of reporting inaccuracies in the outcomes; for example, errors in recalling quit date. Although these issues could lead to overestimating the outcomes, there is no reason to believe they would vary by socioeconomic status and the characteristics of the participants, so the relationship between the outcomes and socioeconomic status as well as the characteristics of the participants would not be affected. Depending on self-reported smoking status without biochemical validation, could be a limitation of this study. Moreover, the actual sample size in the study was much lower than the calculated one due to the high non-response rate, this could have led to non-response bias. Furthermore, the participants social environment was not discussed in the study. However, it is worth mentioning that during the delivery of behavioral interventions to the clients, doctors discuss the social life of the clients which somewhat covers this very important aspect in smoking cessation among individuals.

6 Recommendations

The following recommendations are suggested:

-

i.

The smoking cessation services provided with PHCC are apparently effective both in short and long term and this model of care can be further upscaled by active community engagement.

-

ii.

The policy makers need to be actively engaged by sharing the findings of the study to revisit the regulatory measures that attempt to cut back on selling cigarettes in Qatar.

-

iii.

Health education campaigns and preventive strategies should be devised to prevent the spread of modern alternatives for cigarettes such as vapes, pipes, and other tobacco products since they aren’t widely spread or available in Qatar tobacco markets.

-

iv.

Smoking cessation interventions within the PHCC should specifically focus on high-risk population (individuals below the age of 30, Arab people including Qatari citizens and cohort of highly educated and high income) as indicated by the main findings of the study.

-

v.

Further research including mix methods study (quantitative and qualitative) should be conducted to explore the wider determinants of health that may influence smoking cessation and aid in implementing preventive strategies.

7 Conclusion

The study comprehensively examined the various client factors and smoking cessation interventions practiced within a highly organized primary health care setting. The findings of the study substantiate the effectiveness of the interventions both in short- and long-term basis. There is a need to target high risk individuals and upscale the accessibility to the service among the local population by active community engagement, promoting a multi-sectoral approach strengthening legislative and policy measure for smoking cessation services and further advertisement of the existing services.

Data availability

The datasets used and/or analyzed during the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

References

Jha P. Avoidable deaths from smoking: a global perspective. Public Health Rev. 2011;33:569–600.

Jha P, Peto R. Global effects of smoking, of quitting, and of taxing tobacco. N Engl J Med. 2014;370(1):60–8.

Collaborators GT. Spatial, temporal, and demographic patterns in prevalence of smoking tobacco use and attributable disease burden in 204 countries and territories, 1990–2019: a systematic analysis from the Global Burden of Disease Study 2019. Lancet (London, England). 2021;397(10292):2337.

Organisation. WH. Tobacco 2022. https://www.who.int/news-room/fact-sheets/detail/tobacco. Accessed 6 Jul 2023.

Benjamin EJ, Virani SS, Callaway CW, Chamberlain AM, Chang AR, Cheng S, et al. Heart disease and stroke statistics-2018 update: a report from the American Heart Association. Circulation. 2018;137(12):e67–492.

Cigarette use among high school students--United States, 1991–2005. MMWR. 2006;55(26):724–6.

Krist AH, Davidson KW, Mangione CM, Barry MJ, Cabana M, Caughey AB, et al. Interventions for tobacco smoking cessation in adults, including pregnant persons: US Preventive Services Task Force recommendation statement. JAMA. 2021;325(3):265–79.

Al Mulla A, Yassoub NH, Fu D, El Awa F, Alebshehy R, Ismail M, et al. Smoking cessation services in the Eastern Mediterranean Region: highlights and findings from the WHO Report on the Global Tobacco Epidemic 2019. East Mediterr Health J. 2020;26(1):110–5.

Bauld L, Bell K, McCullough L, Richardson L, Greaves L. The effectiveness of NHS smoking cessation services: a systematic review. J Public Health. 2010;32(1):71–82.

Organization WH. WHO framework convention on tobacco control. WHO Regional Office for South-East Asia; 2004.

Shibuya K, Ciecierski C, Guindon E, Bettcher DW, Evans DB, Murray CJ. WHO Framework Convention on Tobacco Control: development of an evidence based global public health treaty. BMJ. 2003;327(7407):154–7.

Dai X, Gakidou E, Lopez AD. Evolution of the global smoking epidemic over the past half century: strengthening the evidence base for policy action. Tob Control. 2022;31(2):129–37.

Pbert L, Farber H, Horn K, Lando HA, Muramoto M, O’Loughlin J, et al. State-of-the-art office-based interventions to eliminate youth tobacco use: the past decade. Pediatrics. 2015;135(4):734–47.

General US. Preventing Tobacco Use Among Youth and Young Adults. 2012.

Wang TW, Kenemer B, Tynan MA, Singh T, King B. Consumption of Combustible and Smokeless Tobacco - United States, 2000–2015. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2016;65(48):1357–63.

Corey CG, Ambrose BK, Apelberg BJ, King BA. Flavored tobacco product use among middle and high school students-United States, 2014. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2015;64(38):1066–70.

Dierker L, Rose J, Selya A, Piasecki TM, Hedeker D, Mermelstein R. Depression and nicotine dependence from adolescence to young adulthood. Addict Behav. 2015;41:124–8.

Rubinstein ML, Rait MA, Prochaska JJ. Frequent marijuana use is associated with greater nicotine addiction in adolescent smokers. Drug Alcohol Depend. 2014;141:159–62.

Jha P, Ramasundarahettige C, Landsman V, Rostron B, Thun M, Anderson RN, et al. 21st-century hazards of smoking and benefits of cessation in the United States. N Engl J Med. 2013;368(4):341–50.

Baumeister SE, Schumann A, Meyer C, John U, Völzke H, Alte D. Effects of smoking cessation on health care use: Is elevated risk of hospitalization among former smokers attributable to smoking-related morbidity? Drug Alcohol Depend. 2007;88(2–3):197–203.

Lightwood J. The economics of smoking and cardiovascular disease. Prog Cardiovasc Dis. 2003;46(1):39–78.

Raghuveer G, White DA, Hayman LL, Woo JG, Villafane J, Celermajer D, et al. Cardiovascular consequences of childhood secondhand tobacco smoke exposure: prevailing evidence, burden, and racial and socioeconomic disparities: a scientific statement from the American Heart Association. Circulation. 2016;134(16):e336–59.

Siu AL. Behavioral and pharmacotherapy interventions for tobacco smoking cessation in adults, including pregnant women: U.S. preventive services task force recommendation statement. Ann Intern Med. 2015;163(8):622–34.

Lancaster T, Stead L. Physician advice for smoking cessation. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2004;4:Cd000165.

Boyle RG, Solberg LI, Fiore MC. Electronic medical records to increase the clinical treatment of tobacco dependence: a systematic review. Am J Prev Med. 2010;39(6 Suppl 1):S77-82.

AlMulla A, Mamtani R, Cheema S, Maisonneuve P, BaSuhai JA, Mahmoud G, et al. Epidemiology of tobacco use in Qatar: prevalence and its associated factors. PLoS ONE. 2021;16(4): e0250065.

2012 WHOQSS. Qatar STEPS Survey. 2012.

Primary Health Care Corporation Q. Clinical practice guideline for smoking cessation. 2016.

Brookmeyer RCJ. A confidence interval for the median survival time. Biometrics. 1982;38:29–41.

Mansoura FI, Salama RE. Profile of smoking among primary healthcare doctors in Doha, Qatar 2007. Qatar Med J. 2010;2010:2.

Mandil A, BinSaeed A, Ahmad S, Al-Dabbagh R, Alsaadi M, Khan M. Smoking among university students: a gender analysis. J Infect Public Health. 2010;3(4):179–87.

Carnazza G, Liberati P, Resce G, Molinaro S. Smoking and income distribution: Inequalities in new and old products. Health Policy. 2021;125(2):261–8.

Papagiannis D, Malli F, Papathanasiou IV, Routis P, Fradelos E, Kontopoulou L, et al. Attitudes and smoking prevalence among undergraduate students in central Greece. GeNeDis 2020: Springer; 2021. p. 1–7.

Mallol J, Urrutia-Pereira M, Mallol-Simmonds MJ, Calderón-Rodríguez L, Osses-Vergara F, Matamala-Bezmalinovic A. Prevalence and determinants of tobacco smoking among low-income urban adolescents. Pediatr Allergy Immunol Pulmonol. 2021;34(2):60–7.

Güngen AC, Tekeşin A, Koç AS, Güngen BD, Tunç A, Yıldırım A, et al. The effects of cognitive and emotional status on smoking cessation. Eur Rev Med Pharmacol Sci. 2022;26(14):5092–7.

(CDC) CfDCaP. Electronic Nicotine Delivery Systems Key Facts Infographic 2014. https://chronicdata.cdc.gov/Policy/Electronic-Nicotine-Delivery-Systems-Key-Facts-Inf/nwhw-m4ki.

Martins RS, Junaid MU, Khan MS, Aziz N, Fazal ZZ, Umoodi M, et al. Factors motivating smoking cessation: a cross-sectional study in a lower-middle-income country. BMC Public Health. 2021;21(1):1419.

van den Brand FA, Nagtzaam P, Nagelhout GE, Winkens B, van Schayck CP. The association of peer smoking behavior and social support with quit success in employees who participated in a smoking cessation intervention at the workplace. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2019;16(16):2831.

Li L, Borland R, O’Connor RJ, Fong GT, McNeill A, Driezen P, et al. The association between smokers’ self-reported health problems and quitting: findings from the ITC Four Country Smoking and Vaping Wave 1 Survey. Tob Prev Cessation. 2019. https://doi.org/10.18332/tpc/114085.

Primack BA, Sidani J, Agarwal AA, Shadel WG, Donny EC, Eissenberg TE. Prevalence of and associations with waterpipe tobacco smoking among US university students. Ann Behav Med. 2008;36(1):81–6.

Echer IC, Barreto SSM. Determination and support as successful factors for smoking cessation. Rev Lat Am Enfermagem. 2008;16:445–51.

Sohlberg T. Smoking cessation and gender differences—results from a Swedish sample. Nordic Stud Alcohol Drugs. 2015;32(3):259–76.

Chen D, Wu LT. Smoking cessation interventions for adults aged 50 or older: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Drug Alcohol Depend. 2015;154:14–24.

Villanti AC, Bover Manderski MT, Gundersen DA, Steinberg MB, Delnevo CD. Reasons to quit and barriers to quitting smoking in US young adults. Fam Pract. 2016;33(2):133–9.

West R, McEwen A, Bolling K, Owen L. Smoking cessation and smoking patterns in the general population: a 1-year follow-up. Addiction (Abingdon, England). 2001;96(6):891–902.

Harwood GA, Salsberry P, Ferketich AK, Wewers ME. Cigarette smoking, socioeconomic status, and psychosocial factors: examining a conceptual framework. Public Health Nurs. 2007;24(4):361–71.

Fagan P, Shavers V, Lawrence D, Gibson JT, Ponder P. Cigarette smoking and quitting behaviors among unemployed adults in the United States. Nicotine Tob Res. 2007;9(2):241–8.

Anthonisen NR, Skeans MA, Wise RA, Manfreda J, Kanner RE, Connett JE. The effects of a smoking cessation intervention on 145-year mortality: a randomized clinical trial. Ann Intern Med. 2005;142(4):233–9.

Babb S, Malarcher A, Schauer G, Asman K, Jamal A. Quitting smoking among adults—United States, 2000–2015. Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2017;65(52):1457–64.

Niedzin M, Gaszyńska E, Krakowiak J, Saran T, Szatko F, Kaleta D. Gender, age, social disadvantage and quitting smoking in Argentina and Uruguay. Ann Agric Environ Med. 2018;25(1):100–7.

Suls JM, Luger TM, Curry SJ, Mermelstein RJ, Sporer AK, An LC. Efficacy of smoking-cessation interventions for young adults: a meta-analysis. Am J Prev Med. 2012;42(6):655–62.

Villanti AC, McKay HS, Abrams DB, Holtgrave DR, Bowie JV. Smoking-cessation interventions for US young adults: a systematic review. Am J Prev Med. 2010;39(6):564–74.

Kviz FJ, Clark MA, Crittenden KS, Warnecke RB, Freels S. Age and smoking cessation behaviors. Prev Med. 1995;24(3):297–307.

Pesce G, Marcon A, Calciano L, Perret JL, Abramson MJ, Bono R, et al. Time and age trends in smoking cessation in Europe. PLoS ONE. 2019;14(2): e0211976.

Kim Y. Perceived social status and unhealthy habits in Korea. Drug Alcohol Depend. 2019;194:1–5.

Ramsey MW Jr, Chen-Sankey JC, Reese-Smith J, Choi K. Association between marital status and cigarette smoking: variation by race and ethnicity. Prev Med. 2019;119:48–51.

Alboksmaty A, Agaku IT, Odani S, Filippidis FT. Prevalence and determinants of cigarette smoking relapse among US adult smokers: a longitudinal study. BMJ Open. 2019;9(11): e031676.

Ward KD, Klesges RC, Zbikowski SM, Bliss RE, Garvey AJ. Gender differences in the outcome of an unaided smoking cessation attempt. Addict Behav. 1997;22(4):521–33.

Khuder SA, Dayal HH, Mutgi AB. Age at smoking onset and its effect on smoking cessation. Addict Behav. 1999;24(5):673–7.

Siahpush M, Carlin JB. Financial stress, smoking cessation and relapse: results from a prospective study of an Australian national sample. Addiction (Abingdon, England). 2006;101(1):121–7.

Stuber J, Galea S, Link BG. Smoking and the emergence of a stigmatized social status. Soc Sci Med. 2008;67(3):420–30.

Kotz D, West R. Explaining the social gradient in smoking cessation: it’s not in the trying, but in the succeeding. Tob Control. 2009;18(1):43–6.

Reid JL, Hammond D, Boudreau C, Fong GT, Siahpush M. Socioeconomic disparities in quit intentions, quit attempts, and smoking abstinence among smokers in four western countries: findings from the International Tobacco Control Four Country Survey. Nicotine Tob Res. 2010;12(suppl 1):S20–33.

Reid JL, Hammond D, Driezen P. Socio-economic status and smoking in Canada, 1999–2006: has there been any progress on disparities in tobacco use? Can J Public Health. 2010;101:73–8.

Kendzor DE, Businelle MS, Costello TJ, Castro Y, Reitzel LR, Cofta-Woerpel LM, et al. Financial strain and smoking cessation among racially/ethnically diverse smokers. Am J Public Health. 2010;100(4):702–6.

Puente D, Cabezas C, Rodriguez-Blanco T, Fernández-Alonso C, Cebrian T, Torrecilla M, et al. The role of gender in a smoking cessation intervention: a cluster randomized clinical trial. BMC Public Health. 2011;11(1):369.

Takagi D, Kondo N, Takada M, Hashimoto H. Differences in spousal influence on smoking cessation by gender and education among Japanese couples. BMC Public Health. 2014;14(1):1184.

Espinoza LA, Monge-Nájera J. Effect of marital status, gender and job position in smoking behavior and cessation intent of staff members in a Central American public university. UNED Res J. 2013;5(1):157–61.

García-Rodríguez O, Secades-Villa R, Flórez-Salamanca L, Okuda M, Liu SM, Blanco C. Probability and predictors of relapse to smoking: results of the National Epidemiologic Survey on Alcohol and Related Conditions (NESARC). Drug Alcohol Depend. 2013;132(3):479–85.

Koçak ND, Eren A, Boğa S, Aktürk ÜA, Öztürk ÜA, Arınç S, et al. Relapse rate and factors related to relapse in a 1-year follow-up of subjects participating in a smoking cessation program. Respir Care. 2015;60(12):1796–803.

Smith PH, Bessette AJ, Weinberger AH, Sheffer CE, McKee SA. Sex/gender differences in smoking cessation: a review. Prev Med. 2016;92:135–40.

Rodríguez-Cano R, López-Durán A, Martínez-Vispo C, Becoña E. Causes of smoking relapse in the 12 months after smoking cessation treatment: affective and cigarette dependence–related factors. Addict Behav. 2021;119: 106903.

Wang R, Shenfan L, Song Y, Wang Q, Zhang R, Kuai L, et al. Smoking relapse reasons among current smokers with previous cessation experience in Shanghai: a cross-sectional study. Tob Induc Dis. 2023;21:1–13.

Park-Lee E, Ren C, Sawdey MD, Gentzke AS, Cornelius M, Jamal A, et al. Notes from the field: e-cigarette use among middle and high school students—National Youth Tobacco Survey, United States, 2021. Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2021;70(39):1387.

Hair EC, Barton AA, Perks SN, Kreslake J, Xiao H, Pitzer L, et al. Association between e-cigarette use and future combustible cigarette use: Evidence from a prospective cohort of youth and young adults, 2017–2019. Addict Behav. 2021;112: 106593.

Travis N, Levy DT, McDaniel PA, Henriksen L. Tobacco retail availability and cigarette and e-cigarette use among youth and adults: a scoping review. Tob Control. 2021. https://doi.org/10.1136/tobaccocontrol-2020-056376.

Bhatnagar A, Maziak W, Eissenberg T, Ward KD, Thurston G, King BA, et al. Water pipe (hookah) smoking and cardiovascular disease risk: a scientific statement from the American Heart Association. Circulation. 2019;139(19):e917–36.

Patil S, Awan KH, Arakeri G, Aljabab A, Ferrari M, Gomes CC, et al. The relationship of “shisha”(water pipe) smoking to the risk of head and neck cancer. J Oral Pathol Med. 2019;48(4):278–83.

Wang J-H, Yang Y-F, Zhao S-L, Liu H-T, Xiao L, Sun L, et al. Attitudes and influencing factors associated with smoking cessation: an online cross-sectional survey in China. Tob Induc Dis. 2023;21(June):1–9.

East K, McNeill A, Thrasher JF, Hitchman SC. Social norms as a predictor of smoking uptake among youth: a systematic review, meta-analysis and meta-regression of prospective cohort studies. Addiction (Abingdon, England). 2021;116(11):2953–67.

Marsh L, Vaneckova P, Robertson L, Johnson TO, Doscher C, Raskind IG, et al. Association between density and proximity of tobacco retail outlets with smoking: a systematic review of youth studies. Health Place. 2021;67: 102275.

Mayer M, Reyes-Guzman C, Grana R, Choi K, Freedman ND. Demographic characteristics, cigarette smoking, and e-cigarette use among US adults. JAMA Netw Open. 2020;3(10):e2020694.

Wang RJ, Bhadriraju S, Glantz SA. E-cigarette use and adult cigarette smoking cessation: a meta-analysis. Am J Public Health. 2021;111(2):230–46.

Osibogun O, Bursac Z, Maziak W. E-cigarette use and regular cigarette smoking among youth: population assessment of tobacco and health study (2013–2016). Am J Prev Med. 2020;58(5):657–65.

Mansoura FI, Abdulmalik MA, Salama RE. Profile of smoking among primary healthcare doctors in Doha, Qatar 2007. Qatar Med J. 2010. https://doi.org/10.5339/qmj.2010.2.14.

Fu SS, Burgess D, van Ryn M, Hatsukami DK, Solomon J, Joseph AM. Views on smoking cessation methods in ethnic minority communities: a qualitative investigation. Prev Med. 2007;44(3):235–40.

Liu JJ, Wabnitz C, Davidson E, Bhopal RS, White M, Johnson MR, et al. Smoking cessation interventions for ethnic minority groups—a systematic review of adapted interventions. Prev Med. 2013;57(6):765–75.

Altunsoy S, Karadoğan D, Telatar TG, Şahin Ü. Long-term outcomes of smoking cessation outpatient clinic: a single center retrospective cohort study from the Eastern Black Sea Region of Türkiye. Population Medicine. 2024;6(February):1–10.

Reid JL, Hammond D, Boudreau C, Fong GT, Siahpush M, Collaboration obotI. Socioeconomic disparities in quit intentions, quit attempts, and smoking abstinence among smokers in four western countries: Findings from the International Tobacco Control Four Country Survey. Nicotine Tob Res. 2010;12(suppl 1):S20–33.

Acknowledgements

The authors acknowledge all data collectors, the Department of Clinical Research and Department of Health Information Management at PHCC in Qatar for their support toward the study.

Funding

This study got funds from the Primary Health Care Corporation in Qatar during the period of data collection and data analysis. The same corporation will pay partially for the publishing process.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

AAZ wrote the main manuscript text. HM drafted the manuscript. AIF prepared the tables. HAM supervised the data collection and quality of the data collected as well as participated in interpretation of the findings. ASN did the data analysis. MUS did the linguistic review. MAS interpretated the findings. All authors participated in designing the study and in collecting. All authors reviewed the manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate

This study has been performed in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki and have been approved by the Primary Health Care Corporation’s Institutional Review Board (PHCC-IRB) in Qatar. Informed consent form have been obtained from all participants in this study, either directly from the participant or from his/her legal guardian in case of illiterate or below the age of consent (< 18 years of age).

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Competing interests

All authors declared that they have no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary Information

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/. The Creative Commons Public Domain Dedication waiver (http://creativecommons.org/publicdomain/zero/1.0/) applies to the data made available in this article, unless otherwise stated in a credit line to the data.

About this article

Cite this article

Zainel, A.A., Al Mujalli, H., Yfakhroo, A.I. et al. Investigating the socio-demographic characteristics and smoking cessation incidence among smokers accessing smoking cessation services in primary care settings of Qatar, a Historical Cohort Study. Discov Public Health 21, 3 (2024). https://doi.org/10.1186/s12982-024-00124-x

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/s12982-024-00124-x