Abstract

Background

In spite of the global decreasing mortality associated with HIV, adolescents living with HIV (ADLHIV) in sub-Saharan Africa still experience about 50% mortality rate. We sought to evaluate survival rates and determinants of mortality amongst ADLHIV receiving antiretroviral therapy (ART) in urban and rural settings.

Methods

A multi-centered, 10-year retrospective, cohort-study including ADLHIV on ART ≥ 6 months in the urban and rural settings of the Centre Region of Cameroon. Socio-demographic, clinical, biological, and therapeutic data were collected from files of ADLHIV. The Kaplan–Meier method was used to estimate survival probability after ART initiation; the log rank test used to compare survival curves between groups of variables; and the Cox proportional hazard model was used to identify the determinants of mortality.

Results

A total of 403 adolescents’ records were retained; 340 (84%) were from the urban and 63 (16%) from the rural settings. The female to male ratio was 7:5; mean age (Standard deviation) was 14.1 (2.6) years; at baseline, 64.4% were at WHO clinical stages I/II, 34.9% had ≥ 500 CD4 cells/mm3, 91.1% were anemic, and the median [Inter Quartile Range] duration on ART was5.3 [0.5–16] years. The survival rate at 1, 5 and 10 years on ART was respectively 97.0%, 55.9% and 8.7%; with mean survival time of 5.8 years (95% CI 5.5–6.1). In bivariate analysis, living in the rural setting, non-disclosed HIV status, baseline CD4 count < 500 cells/mm3, not being exposed to nevirapine prophylaxis at birth and being horizontally infected were found to be the determinants of higher mortality with poor retention in care slightly associated with mortality. In multivariate analysis, living in rural settings, poor retention in care and anemia were independent predictors of mortality (p < 0.05).

Conclusion

Although ADLHIV have good survival rate on ART after 1 year, we observe poor survival rates after 5 years and especially 10 years of treatment experience. Mitigating measures against poor survival should target those living in rural settings, anemic at baseline, or experiencing poor retention in care.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Human Immunodeficiency Virus/Acquired Immune Deficiency syndrome epidemic (HIV/AIDS) continues to be a major global public health issue. In 2022, an estimated 39 million people globally were living with HIV/AIDS [1]. In this same year, about 1.7 million adolescents between the ages of 10 and 19 were reported to be living with HIV worldwide, accounting for about four percent of all people living with HIV and about 10 percent of all new infections [2]. Of these, about 1.4 million (that is 85 per cent), live in sub-Saharan Africa, which remains the most affected region even in this adolescent population [2, 3]. The prevalence of HIV in Cameroon as of 2018, is 2.7% with 0.8% occurring among adolescents aged 15–19 [4]

Antiretroviral treatment (ART) has improved the survival of HIV-infected patients by inhibiting the viral replication, which in turn boosts the immune system through increased CD4 count, decreases in HIV/AIDS-associated manifestations, and minimizes the risk of opportunistic infections (OIs). However, taking into consideration non-adherence and drug resistance that may lead to poor responses, some patients might have suboptimal response to ART and remain at risk of HIV-associated morbidity and mortality [5]. Despite the overall decrease in HIV-related deaths in the general population, the proportion of deaths among adolescents have more than doubled during the period of 2000 to 2015 [6]. Indeed, adolescents living with HIV (ADLHIV) are the only age group with increasing HIV mortality in the current ART era, they have poor clinical and programmatic outcomes at each stage of the HIV care cascade, with increasing mortality rate as these adolescents grow older [7, 8].

HIV programs are increasingly recognizing adolescents as a critical age group. Nonetheless, adolescents continue to be underserved by current services across the HIV cascade. They have significantly inferior ART access and coverage, higher rates of loss to follow-up, poor adherence, and increased needs for psychosocial support and sexual reproductive health services [9]. These challenges are also associated with increased risks of virological failure and HIV drug resistance (HIVDR) emergence which is a threat to ART effectiveness in Sub-Saharan African health programs, including Cameroon [10, 11]. Of note, the prevalence of baseline HIVDR in pediatric population in Cameroon is around 50%, essentially driven by mutations associated with non-nucleoside reverse-transcriptase inhibitors (NNRTI) [12]. Furthermore, Cameroonian adolescents receiving ART were found with 34.2% rate of virological failure and over 90% rate of HIVDR among those experiencing treatment failure in the Centre region of the country [11, 12]. Hence adolescents are now recognized as a distinct population, and have been described as the ‘fulcrum’ and the center of the epidemic’ with different health requirements for children as compared to adults [9, 13]. In this context, identifying drivers of survival and mortality among adolescents, according to geographical localities in resourced-limited and HIV high-burdened countries, would be of paramount importance in defining gaps in the AIDS response. This study therefore aimed at assessing the survival rates of ADLHIV on ART and to identify the determinants of mortality in urban and rural settings of Cameroon.

Methods

Study design and settings

We carried out a multi-centred, 10-year retrospective cohort study among ADLHIV receiving ART from January 1st, 2010 to December 31st, 2019. Data was extracted from patients’ files sequentially from ART initiation till they were either lost to follow up, dead or till the end of the study period.

Our study population included ADLHIV having been on ART for at least 6 months in 6 HIV treatment centres in the urban and rural areas of the Centre Region of Cameroon. These were two approved HIV treatment centres in the urban setting namely (the Mother–Child centre of the Chantal BIYA Foundation and the National Social Welfare Hospital Yaoundé), and four HIV managements units in the rural setting (the Mbalmayo District Hospital, the Mfou District hospital, the Nkomo integrated health centre and the Bikop Catholic Medical centre). These sites were conveniently selected based on the geographical areas (urban vs. rural), availability of at least first line ART, experience in providing ART for at least 3 years and use of standard patient monitoring registers.

Data collection

We collected data from adolescents’ medical records and ART files using a study-specific data collection form. The data extracted from records included: socio-demographic data (age, gender, parental status, area of residence, level of education, and disclosure of HIV to study participants). Clinical data (WHO clinical stage, mode of transmission, presence of opportunistic infection); biological data (baseline CD4 count at start, endpoint CD4 count, hemoglobin at start) were retrieved; therapeutic data (treatment regimen, loss to follow up, retention in care, cotrimoxazole prophylaxis, exposure to NVP prophylaxis for PMTCT). Anemia was defined as Hb level below 12 g/dl for female and 13 g/dl for male. The presence of opportunistic infection at any point in time during the study period was collected. Patients who had no contact, 90 days after their last missed pill appointment were considered as being lost to follow-up (LTFU) [14]. As such, we considered retention in care as patients known to be alive and receiving ART at the end of the follow-up in our study, excluding cases of reported deaths.

Study participants, end points and outcome measures

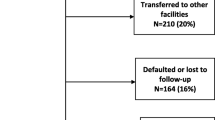

Enrolled were all adolescents aged 10–19 years, followed up during the study period at one of our study sites, having been on ART for at least 6 months. Excluded were all participants who were transferred in or out from different centers during our study period, and participants with incomplete files. Our major end points were participants who died during our study period, or who were lost to follow-up LTFU. Our major outcomes were survival rates and mortality. For survival analysis, all 403 participants enrolled in the study were considered, while adjusting for those who were lost to follow-up.

Statistical analyses and calculation methods

All data collected were checked at the end of each patient file to make sure all sections were adequately reported. We entered these data in Epi Info v7.2.2.6 and analyzed using statistical package for social science (SPSS) version 21. Kaplan–Meier method was used to perform survival analysis, to estimate survival probability after initiation of ART, and the log rank test used to compare survival curves between groups of variables. Cox proportional hazard model was used to identify key predictor of mortality. P-values < 0.05 were considered statistically significant.

Ethical considerations

An ethical clearance was obtained from the Ethical Review Board of the Faculty of Health Sciences, University of Buea (Ref: 2020/1056-01/UB/SG/IRB/FHS) and regional delegation of Public Health of the Centre region, Cameroon (Ref: CE No-3462-/CRERSHC/2020). Administrative approval was obtained from the directors of the various centers prior to the start of the study. The data collection tools were assigned codes and kept anonymous. All data collected during the study was kept strictly confidential and shared only with the investigators and management team of the various centers.

Results

Demographic and clinical characteristics of study population

Of 544 files, we had 403 eligible files of which 340 (84%) were from the urban setting and 63 (16%) from the rural setting. Majority of the study population 232/403 (57.6%) were females with F/M ratio of 7:5. Overall, mean age (± SD) was 14.08 (± 2.6) years. The median [IQR] duration on ART was 5.3 [0.5–16] years. Details on socio-demographic characteristics are presented in Table 1.

Overall, 222/320 (69.4%) were in less-advanced WHO clinical stage (defined as WHO stages I/II); 75/215 (34.9%) of these adolescents had CD4 count ≥ 500 cell/mm3 at start of ART as compared to 54/75 (72%) at end point. When comparing the rate of CD4-recovery from baseline to end point, there was a significant recovery among those in urban settings (from 31.7% to 75.4%, p < 0.0002) as opposed to a slight decline in rural settings (from 55.2% to 50.0%, p = 0.7772). Retention in care on ART was 346/389 (88.9%), with a comparable trend between urban (88.6%) and rural (85.2%) settings. Similarly, the overall rate of lost to follow-up was 9.3%, with a comparable trend between urban (8.5%) and rural (13.3%) settings. Details on medical characteristics are presented in Table 2.

Survival outcome of HIV infected adolescents after initiation of ART

The mean survival time was 69.7 months (95% CI 65.8–73.5) and overall cumulative probabilities of survival respectively at 1, 5 and 10 years after ART initiation were 97%, 55.9% and 8.7%. Of note, there was about 50% decline in survival after about 70 months on ART (see Fig. 1).

Survival rate according to socio-demographic/clinical features

According to orphan hood, adolescents who were non-orphans had a significantly higher survival rate as opposed to those who were orphans; Log Rank p = 0.033 (Fig. 2). Using orphans of both parents as a reference (Fig. 3), there was a similar survival rate with maternal orphans (Log Rank p = 0.411), as opposed to a significantly higher rate of survival among paternal orphans (Log Rank P = 0.044).

Survival curve between orphans both parents and orphan for a single parent (father and mother respectively): on the left, are the survival curves for adolescents who were orphans for both parents (purple) as compared to those who were paternal orphans (green) and on the right are the survival curves for adolescents who were orphans for both parents (purple) as compared to those who were maternal orphans (green)

The survival time was significantly longer among those in the urban settings as compared to those in rural settings (mean survival time 72.9 versus 51.0 months respectively, p < 0.0001), which goes along with the hazard of mortality being 6 times higher. In addition, the survival time was longer among those with a disclosed HIV status (76.9 versus 67.8 months respectively, p = 0.04), as shown in Tables 3, 4.

Determinants of mortality in the study population

We observed a total of 14 deaths, 3 (4.7%) in the rural region and 11 (3.2%) in urban region. With respect to socio-demographic parameters, both the geographical settings (living in rural, p = 0.0001) and non-disclosure of HIV status (p = 0.044) were associated with a higher risk of mortality. Following multivariate analysis, only the geographical setting (living in rural: hazard ratio: 6.5; p = 0.0001) was an independent factor of mortality in our study population (Table 5).

With respect to medical parameters, when assessing factors potentially associated with risk of mortality, univariate analysis revealed that baseline CD4 less than 500 cell/mm3 (p = 0.001), non-exposure to nevirapine prophylaxis for PMTCT (p = 0.014), horizontal mode of HIV transmission (0.001) and anemia (p = 0.001) appeared as determinants of mortality among these adolescents. Following multivariate analysis, only poor retention in care (p = 0.019) and anemia at the start of ART (p = 0.006) were independent predictors of adolescent mortality (see Table 5).

Discussion

With the goal to set-up measures to limit the occurrence of mortality among ADLHIV, our study aimed at assessing the rate of survival and determinants of mortality among ADLHIV receiving ART in urban and rural settings of Cameroon. Overall, the mean survival time was 69.7 months with a good survival rate at 1 year (97%), which significantly reduced at 5 years (55.9%) and 10 years (8.7%). These results are different from other findings, which suggest poorer survival rates soon after ART initiation. Lumbiganon et al. in 2011 described poor rates of survival soon after ART initiation, with a higher 5-year survival rate of 91.7% [15]. This higher survival rate could be due to the predominantly child population in their study, consistent with findings in our context at this time [7, 21]. The overall mean survival time in our study is not too different from findings by Arage et al. in Ethiopia (91.6 months). This slight difference can however be explained by the fact that, Arage et al. worked on a much younger population (2 months to 14 years) [5]. It is worth noting that Fokam et al. showed better treatment outcomes in children as compared to adolescent before 2019, therefore explaining the lower survival rates in our adolescent population at this time [16]. Furthermore, a number of factors and evidence concerning ADLHIV in the Cameroonian context could explain the high mortality rates observed in our study. A study in conducted by our same team (Fokam et al.) in 2017 showed that in the long term, ADLHIV were faced with risks of adherence problems and viral rebound [17]. Furthermore, long periods of treatment with low genetic barrier ARV drugs in this resource limited setting, lead to high rates of virological failure and HIV drug resistance in this target population. To add, the same team in 2019 showed declining rates of virological success after 36 months of treatment on NNRTI regimes, driven by poor adherence and probably emergence of drug resistance mutations to NNRTI which have a low genetic barrier. In 2020, Dambaya et al. described rates of 52.6% for overall drug resistance in treatment naïve patients (NNRTI resistance consisting 31.6%), with rates of NNRTI resistance as high as 90%, similar to findings by Fokam et al. in 2021 [11, 12]. Lastly, the majority of our adolescents were either single or double parent orphans, with most of them not knowing their status (non-disclosure). All these above-mentioned points could therefore explain the high mortality in our study, especially long after initiation (significantly after 5 years in our study). This therefore again calls for specific/adapted monitoring strategies in this population as they grow older.

Adolescents living in the rural setting had about six-fold risk of mortality as compared to those in urban settings. This is in line with challenges on timely access to ART and retention in the continuum of care in these rural settings [18]. To add, rural settings are faced with problems in administering HIV management and care, such as poor adherence to ART program and viral load coverage as described by Fokam et al. in 2020 [19]. This therefore calls for the effective implementation and scale up of better strategies such as community dispensation of ART and even HIV services (such as viral load testing) in rural areas, so as to fill this gap, while also mitigating the high patient-to-staff ratio (i.e. higher workload) and distances from healthcare centers in rural settings [12, 22]. It is worth noting that, community dispensation of ART was initiated in Cameroon in 2016, but needs to be expanded from urban areas (where the large majority of patients and treatment centers are located) to rural settings, so as to improve the availability of ART in the rural setting [20].

Elsewhere, poor retention in care was associated with higher rates of mortality as adolescents with poor retention in care had 2.4 times the risk of mortality as compared to those with good retention in care. These results are not surprising, as the benefits of retention in care cannot be overemphasized. In 2019, Ulloa et al. showed a marked decrease of mortality in patients who were successfully retained in care. Key interventions are therefore needed to solve this problem. A patient-centered approach, (by leveraging on the adolescent’s strengths for positive encouragements and by educating adolescents on healthy lifestyles to improve treatment adherence), might help [21,22,23]. This requires emphasis on specific healthcare needs of adolescents, the setting-up of adolescent- and youth-friendly health services, adolescent HIV guidelines/policies, peer mentoring with the real-life example of RECAJ + in Cameroon and other key adolescent-specific issues (i.e. intrinsic factors such as adolescent behaviors) [24].

Lastly, adolescents who were anemic had about fivefold increased risk of mortality, as compared to non-anemic adolescents. This is consistent with findings by Harding et al.in the United States, who described anemia as a predictor of mortality [25]. Also, Biru et al., reported anemia as being a predictor of attrition in children [26]. While continuing monitoring of anemia under zidovudine-containing regimens is essential, investigating the effect of advanced HIV disease at diagnosis or other contributing pathology on mortality risk is needed [27]. Given the relatively low cost of assessing anemia, this event can be used frequently to identify high-risk ADLHIV in such settings [27, 28].

Despite the successful completion of our study objectives, missing or poor records for some participants limit the statistical strength we would have loved to have. Nonetheless, the overall high sample size of the target population, the exhaustive sampling strategy in the study sites and our study design as a whole were potential strengths of our study. As perspectives, assessing the impact of delayed ART initiation on health outcomes, particularly among adolescents with congenital HIV-infection, is a research gap that we would love to cover in subsequent studies.

Conclusion

There is a significant decreasing survival among ADLHIV on ART in the Centre region of Cameroon. Of note, ADLHIV on ART in the rural setting experience higher risk of mortality as compared to their peers in the urban settings. Irrespective of geographical settings, poor retention in care and anemia might be predictors of mortality among ADLHIV on ART. Thus, setting-up adolescent-friendly centers, peer mentoring and community provision of ART could substantially improve survival in Cameroon.

Availability of data and materials

Data supporting the findings are fully available in the results, in the tables and figures of the manuscript.

Abbreviations

- ADLHIV:

-

Adolescent living with HIV

- AIDS:

-

Acquired Immuno-deficiency Syndrome

- ART:

-

Antiretroviral therapy

- CD4:

-

Cluster differentiation 4

- HAART:

-

Highly Active Antiretroviral Treatment

- HIV:

-

Human immuno deficiency virus

- HIVDR:

-

HIV drug resistance

- LTFU:

-

Loss to follow up

- NNRTIs:

-

Non-nucleoside reverse transcriptase inhibitors

- NRTIs:

-

Nucleoside reverse transcriptase inhibitors

- NVP:

-

Nevirapine

- OI:

-

Opportunistic infections

- PI:

-

Protease inhibitor

- PMTCT:

-

Prevention of mother-to-child transmission

- SSA:

-

Sub-Saharan Africa

- UNAIDS:

-

Joint United Nations programme on HIV/AIDS

- UNDP:

-

United Nations Development Programme

- WHO:

-

World Health Organization

References

AIDSinfo | UNAIDS. https://aidsinfo.unaids.org/. Accessed 9 Sep 2020.

Adolescent HIV prevention. UNICEF DATA. https://data.unicef.org/topic/hivaids/adolescents-young-people/. Accessed 24 Nov 2023.

HIV and AIDS in Adolescents. UNICEF DATA. https://data.unicef.org/topic/adolescents/hiv-aids/. Accessed 28 Aug 2020.

Rapport de la cinquième Enquête Démographique et de Santé du Cameroun (EDSC-V) en 2018. http://www.statistics-cameroon.org/news.php?id=596. Accessed 29 Jun 2020.

Arage G, Assefa M, Worku T, Semahegn A. Survival rate of HIV-infected children after initiation of the antiretroviral therapy and its predictors in Ethiopia: a facility-based retrospective cohort. SAGE Open Med. 2019;7:1–8.

WHO | Adolescent health epidemiology. WHO. 2019. https://www.who.int/maternal_child_adolescent/epidemiology/adolescence/en/. Accessed 23 Nov 2019.

Enane LA, Vreeman RC, Foster C. Retention and adherence: global challenges for the long-term care of adolescents and young adults living with HIV. 2018. https://www.ingentaconnect.com/content/wk/coh/2018/00000013/00000003/art00008. Accessed 23 Nov 2019.

Slogrove AL, Mahy M, Armstrong A, Davies M-A. Living and dying to be counted: what we know about the epidemiology of the global adolescent HIV epidemic. J Int AIDS Soc. 2017;20(Suppl 3):21520.

Armstrong A, Nagata JM, Vicari M, Irvine C, Cluver L, Sohn AH, et al. A global research agenda for adolescents living with HIV. J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr. 1999;2018(78):S16-21.

Same DAKY, Billong SC, Fokam J, Momo PT, Amadou S, Nemb MN, et al. Survival Analysis among Patients receiving Antiretroviral Therapy in Urban and Rural Settings of the Centre Region of Cameroon. Health Sci Dis. 2016;17.

Fokam J, Takou D, Njume D, Pabo W, Santoro MM, Njom Nlend A-E, et al. Alarming rates of virological failure and HIV-1 drug resistance amongst adolescents living with perinatal HIV in both urban and rural settings: evidence from the EDCTP READY-study in Cameroon. HIV Med. 2021;22:567–80.

Dambaya B, Fokam J, Ngoufack ES, Takou D, Santoro MM, Této G, et al. HIV-1 drug resistance and genetic diversity among vertically infected Cameroonian children and adolescents. Explor Res Hypothesis Med. 2020;5:53–61.

Kim S-H, Gerver SM, Fidler S, Ward H. Adherence to antiretroviral therapy in adolescents living with HIV: systematic review and meta-analysis. AIDS Lond Engl. 2014;28:1945–56.

Minsante. directives nationales sur la prise en charge du vih. 2021.

Lumbiganon P, Kariminia A, Aurpibul L, Hansudewechakul R, Puthanakit T, Kurniati N, et al. Survival of HIV-infected children: a cohort study from the Asia-Pacific region. J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr. 1999;2011(56):365.

Fokam J, Sosso SM, Yagai B, Billong SC, Djubgang Mbadie RE, Kamgaing Simo R, et al. Viral suppression in adults, adolescents and children receiving antiretroviral therapy in Cameroon: adolescents at high risk of virological failure in the era of “test and treat.” AIDS Res Ther. 2019;16:36.

Fokam J, Billong SC, Jogue F, Moyo Tetang Ndiang S, Nga Motaze AC, Paul KN, et al. Immuno-virological response and associated factors amongst HIV-1 vertically infected adolescents in Yaoundé-Cameroon. PLoS ONE. 2017;12: e0187566.

Sieleunou I, Souleymanou M, Schönenberger A-M, Menten J, Boelaert M. Determinants of survival in AIDS patients on antiretroviral therapy in a rural centre in the Far-North Province, Cameroon. Trop Med Int Health TM IH. 2009;14:36–43.

Fokam J, Nangmo A, Wandum C, Takou D, Santoro MM, Nlend A-EN, et al. Programme quality indicators of HIV drug resistance among adolescents in urban versus rural settings of the centre region of Cameroon. AIDS Res Ther. 2020;17:14.

Kameni BS, Nansseu JR, Tatah SA, Bigna JJ. Sustaining the community dispensation strategy of HIV antiretroviral through community participation. Infect Dis Poverty. 2019;8:5.

Haas AD, Zaniewski E, Anderegg N, Ford N, Fox MP, Vinikoor M, et al. Retention and mortality on antiretroviral therapy in sub-Saharan Africa: collaborative analyses of HIV treatment programmes. J Int AIDS Soc. 2018;21: e25084.

Ulloa AC, Puskas C, Yip B, Zhang W, Stanley C, Stone S, et al. Retention in care and mortality trends among patients receiving comprehensive care for HIV infection: a retrospective cohort study. CMAJ Open. 2019;7:E236–45.

Cluver L, Pantelic M, Toska E, Orkin M, Casale M, Bungane N, et al. STACKing the odds for adolescent survival: health service factors associated with full retention in care and adherence amongst adolescents living with HIV in South Africa. J Int AIDS Soc. 2018;21: e25176.

Home Cholatse. RéCAJ+. 2023. https://recajplus.com/. Accessed 27 Apr 2023.

Harding BN, Whitney BM, Nance RM, Ruderman SA, Crane HM, Burkholder G, et al. Anemia risk factors among people living with HIV across the United States in the current treatment era: a clinical cohort study. BMC Infect Dis. 2020;20:238.

Biru M, Hallström I, Lundqvist P, Jerene D. Rates and predictors of attrition among children on antiretroviral therapy in Ethiopia: a prospective cohort study. PLoS ONE. 2018;13: e0189777.

Woldeamanuel GG, Wondimu DH. Prevalence of anemia before and after initiation of antiretroviral therapy among HIV infected patients at Black Lion Specialized Hospital, Addis Ababa, Ethiopia: a cross sectional study. BMC Hematol. 2018;18:7.

Haider BA, Spiegelman D, Hertzmark E, Sando D, Duggan C, Makubi A, et al. Anemia, iron deficiency, and iron supplementation in relation to mortality among HIV-infected patients receiving highly active antiretroviral therapy in Tanzania. Am J Trop Med Hyg. 2019;100:1512–20.

Acknowledgements

We thank the clinicians, nurses, laboratory staffs, pharmacists and data clerks who contributed in generating these data in the respective study sites.

Funding

The ‘European and Developing countries Clinical Trial Partnership’ (EDCTP – Career Development Fellowship - TMA 1027) supported in part the funding for this research project, in partnership with CIRCB.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Conceived the study: AN, FLTN, JF, NT. Implemented the study: FLTN, JF, CAC, AN, ND, STNM, A-EN-N, PKN. Analysed the data: FLTN, CC, JF. Interpreted the data: AN, MPH, FLTN, JF, NT Initiated the manuscript: NT, FLTN, JF. Revised the manuscript: CAC, AN, ND, STNM, A-EN-N, PKN, MPH. Approved the final version of the manuscript: all co-authors.

Corresponding authors

Ethics declarations

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Competing interests

All authors declared that they have no competing interest.

Additional information

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/. The Creative Commons Public Domain Dedication waiver (http://creativecommons.org/publicdomain/zero/1.0/) applies to the data made available in this article, unless otherwise stated in a credit line to the data.

About this article

Cite this article

Tendongfor, N., Fokam, J., Chenwi, C.A. et al. Determinants of survival of adolescents receiving antiretroviral therapy in the Centre Region of Cameroon: a multi-centered cohort-analysis. AIDS Res Ther 20, 88 (2023). https://doi.org/10.1186/s12981-023-00584-2

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/s12981-023-00584-2