Abstract

Background

Intensive adherence counseling (IAC) is the global standard of care for people living with human immunodeficiency virus (PLHIV) who have unsuppressed VL after ≥ 6 months of first-line anti-retroviral therapy (ART). We investigated whether the number of IAC sessions is associated with suppressed VL among PLHIV in Kampala, Uganda.

Methods

We conducted a nested case-control study among PLHIV with unsuppressed VL after ≥ 3 IAC sessions (cases) and a 2:1 random sample of PLHIV with suppressed VL after ≥ 3 IAC sessions (controls). Unsuppressed VL was defined as VL ≥ 1000 copies/ml. We performed multivariable logistic regression to identify factors that differed significantly between cases and controls.

Results

Demographic and clinical characteristics were similar among the 16 cases and 32 controls including mean age, sex, baseline CD4 count, VL before IAC, and WHO clinical stage. Only the number of IAC sessions differed significantly between cases and controls in unadjusted (p = 0.012) and adjusted (p = 0.016) analyses. Each unit increase in IAC session was associated with unsuppressed VL (Adjusted odds ratio 5.09; 95% CI 1.35–19.10).

Conclusions

VL remained unsuppressed despite increasing IAC frequency. The fidelity to standardized IAC protocol besides drug resistance testing among PLHIV with unsuppressed VL before IAC commencement should be examined.

Similar content being viewed by others

Background

With optimal ART adherence, nearly all people living with human immunodeficiency virus (PLHIV) achieve viral load (VL) suppression within 6 months of anti-retroviral therapy (ART) initiation. For those with unsuppressed VL, an ART adherence intervention is needed [1]. The World Health Organization (WHO) recommends intensive adherence counseling (IAC) for PLHIV with unsuppressed VL before diagnosing treatment failure and switching to a second-line ART. IAC consists of three targeted and structured counseling and support sessions, spaced 1 month apart, provided by a multidisciplinary team to overcome barriers to ART adherence [2, 3].

Past studies in Uganda [2, 4, 5] show that a significant proportion of PLHIV with an unsuppressed VL never achieve VL suppression even after ≥ 3 IAC sessions but this problem has not been extensively studied. Our study investigated whether the number of IAC sessions is associated with suppressed VL among adolescents and adults living with HIV on first-line ART who had unsuppressed VL after 6 or more months on ART in Kampala, Uganda.

Methods

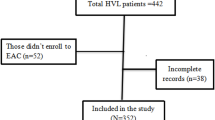

This was a sub-analysis of data from the EFFINAC study [6] that retrieved medical records across six public Kampala Capital City Authority (KCCA) health facilities described previously [7, 8]. The EFFINAC study evaluated the impact of IAC on VL suppression and mortality among PLHIV on first-line ART, with the intervention group as those who had received ≥ 3 consecutive IAC sessions provided 1 month apart (n = 114) and comparison as those who received psychosocial support (n = 3085). The study sites provide standardized HIV/ART care following the national treatment guidelines. The first VL testing is done after 6 months of ART initiation and subsequent tests are done annually if one is virally suppressed. If one is not virally suppressed, IAC is provided according to guidelines. The parent study received ethical approvals from the Infectious Diseases Institute Research Ethics Committee (#IDI-REC-2022-18) and the Uganda National Council for Science and Technology (#HS25553ES), and administrative clearance from the Directorate of Public Health and Environment, KCCA (#DPHE/KCCA/1301). The study considered participants initiated on first-line ART between November 1, 2020, and November 30, 2021, with the data retrieval period as November 1, 2022, to January 5, 2023. For this nested case-control study, the IDI-REC and UNCST provided a waiver of informed consent since the study was embedded within the parent study [6]. PLHIV aged ≥ 15 years with repeat unsuppressed VL (VL ≥ 1000 copies/ml) after ≥ 3 IAC sessions were considered as cases (n = 16) and a 2:1 random sample of those with repeat suppressed VL (VL < 1000 copies/ml) were selected as controls (n = 32).

We excluded PLHIV that transferred to other health facilities and those that died before a repeat VL testing. We summarized numerical data using mean and standard deviation (when normally distributed) and categorical data using frequencies and percentages. Bivariate analysis used Fisher’s exact test to assess differences in proportions between cases and controls. Mean differences in numerical data between cases and controls were assessed using Student’s t-test for normally distributed data, otherwise, the Wilcoxon-rank sum test was used. Socially and clinically relevant variables from the literature and those with p < 0.1 at the bivariate analysis were included in the multivariable logistic regression analysis to determine whether the number of IAC sessions is associated with suppressed VL. We reported odds ratio (aOR) and 95% confidence interval (CI).

Results

Of 114 PLHIV that received ≥ 3 IAC sessions, 67 had repeat VL testing of whom 16 had unsuppressed VL (cases) while 51 had suppressed VL. From the latter category, we randomly sampled 32 participants as controls, yielding a 1:2 case-to-control ratio. Table 1 summarises the participants’ characteristics. On average, cases and controls had comparable mean ages: 26.2 ± 15.7 versus 27.8 ± 9.8 respectively, p = 0.67. We found a borderline difference between cases and controls regarding baseline ART regimen (p = 0.058) but a significant difference concerning the frequency of IAC sessions (P = 0.009). Other variables showed no difference between cases and controls. Each unit increase in IAC frequency was significantly associated with being a case in unadjusted (OR, 4.53; 95% CI 1.39–14.74) and adjusted (aOR, 5.09; 95% CI 1.35–19.10) analyses (Table 2).

Discussion

VL remained unsuppressed despite increasing IAC frequency among PLHIV who had received ≥ 3 IAC sessions. Our findings suggest IAC is ineffective in halting and reversing unsuppressed VL consistent with our finding of a lack of impact of IAC on VL suppression [6]. A Swaziland study showed that VL suppression is not associated with the frequency of IAC sessions as no difference in VL suppression was observed between those who received 1–3 IAC sessions and those with zero IAC [9]. Inadequacies in ART adherence during IAC have been reported to increase the odds of unsuppressed VL [10] and might explain the finding.

However, whether cases had suboptimal ART adherence than the controls despite increasing IAC frequency remains unknown as all participants reported good ART adherence. HIV drug resistance could be another factor as recent evidence shows an increasing trend in drug resistance in pre-treated populations [11]. In South Africa, a substantial proportion of PLHIV with unsuppressed VL after IAC (41/48) had drug resistance [12]. A previous study involving 113 PLHIV on long-term ART who completed IAC in eastern Uganda found more than nine in 10 had unsuppressed VL and drug resistance testing on 105 of the participants revealed 103 (98%) had at least one mutation [4]. HIV drug resistance testing was not routinely performed at the time of our study. However, our data support that drug resistance testing should be done for PLHIV with unsuppressed VL before IAC initiation as IAC will not achieve VL suppression in the presence of drug resistance.

Our study has strengths and limitations to consider. We analyzed data on cases and controls drawn from the same cohort, making the two groups almost similar on several measured factors. Limitations include a small sample size so the evidence should be considered preliminary. We analyzed secondary data so data on HIV drug resistance and IAC implementation fidelity that might explain unsuppressed VL were not available. Future, prospective studies should account for these factors and further explore socio-behavioral factors (e.g., stigma, discrimination, social support) that might contribute to sub-optimal ART adherence and potential worsening of adherence as a result of IAC.

Conclusions and recommendations

An increase in the number of IAC sessions did not achieve VL suppression. We recommend a need to examine the fidelity of IAC implementation and to perform drug resistance testing among PLHIV with unsuppressed VL before IAC initiation and a switch to second or third-line ART.

Availability of data and materials

The datasets used and/or analysed during the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

Abbreviations

- ART:

-

Anti-retroviral therapy

- HIV:

-

Human immunodeficiency virus

- IAC:

-

Intensive adherence counseling

- PLHIV:

-

People living with HIV

- VL:

-

Viral load

References

Bonner K, Mezochow A, Roberts T, Ford N, Cohn J. Viral load monitoring as a tool to reinforce adherence: a systematic review. JAIDS J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr. 2013;64(1):74–8.

Lukyamuzi Z, Etajak S, Katairo T, Mukunya D, Tetui M, Ssenyonjo A, et al. Effect and implementation experience of intensive adherence counseling in a public HIV care center in Uganda: a mixed-methods study. BMC Infect Dis. 2021;21:1168.

Ndikabona G, Alege JB, Kirirabwa NS, Kimuli D. Unsuppressed viral load after intensive adherence counselling in rural eastern Uganda; a case of Kamuli district, Uganda. BMC Public Health. 2021;21(1):1–13.

Birungi J, Cui Z, Okoboi S, Kapaata A, Munderi P, Mukajjanga C, et al. Lack of effectiveness of adherence counselling in reversing virological failure among patients on long-term antiretroviral therapy in rural Uganda. HIV Med. 2020;21(1):21–9.

Kikaire B, Ssemanda M, Asiimwe A, Nakanwagi M, Seruwagi G, Lawoko S, et al. HIV viral suppression viral load suppression following intensive adherence counseling among people living on treatment at military-managed health facilities in Uganda. Int J Infect Dis. 2021. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijid.2021.08.057.

Izudi J, Castelnuovo B, King R, Cattamanchi A. Impact of intensive adherence counseling on viral load suppression and mortality among people living with HIV in Kampala, Uganda: a regression discontinuity design. PLOS Glob Public Health. 2023;3(8): e0002240.

Izudi J, Sheira LA, Bajunirwe F, McCoy SI, Cattamanchi A. Effect of 6-month vs. 8-month regimen on retreatment success for pulmonary TB. Int J Tuberc Lung Dis. 2022;26(12):1188–90.

Izudi J, Bajunirwe F, Cattamanchi A. Increase in rifampicin resistance among people previously treated for TB. Public Health Act. 2023;13(1):4–6.

Jobanputra K, Parker LA, Azih C, Okello V, Maphalala G, Kershberger B, et al. Factors associated with virological failure and suppression after enhanced adherence counselling, in children, adolescents and adults on antiretroviral therapy for HIV in Swaziland. PLoS ONE. 2015;10(2): e0116144.

Bisetegn G, Arefaynie M, Mohammed A, Fentaw Z, Muche A, Dewau R, et al. Predictors of virological failure after adherence-enhancement counseling among first-line adults living with HIV/AIDS in Kombolcha Town, Northeast Ethiopia. HIV/AIDS (Auckland, NZ). 2021;13:91–7.

Bessong PO, Matume ND, Tebit DM. Potential challenges to sustained viral load suppression in the HIV treatment programme in South Africa: a narrative overview. AIDS Res Ther. 2021;18(1):1.

Fox MP, Berhanu R, Steegen K, Firnhaber C, Ive P, Spencer D, et al. Intensive adherence counselling for HIV-infected individuals failing second‐line antiretroviral therapy in Johannesburg, South Africa. Trop Med Int Health. 2016;21(9):1131–7.

Acknowledgements

We are momentously indebted to the IDI-REC for providing an ethical review and approval. We thank the Directorate of Public Health and Management of the Kampala Capital City Authority for their administrative support. The Heads of the Health Facilities at the respective study sites, the HMIS focal persons, and Philip Kalyesubula of Infectious Diseases Institute Makerere University are immensely appreciated for their support.

Funding

This project was supported by the Fogarty International Center of the National Institutes of Health (NIH) under Award Number D43TW009343 and the University of California Global Health Institute (UCGHI). The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the NIH or UCGHI. The KCCA HIV clinics are supported by funding from the Government of Uganda (GR-G-0902) and the President’s Emergency Plan for AIDS Relief through the United States Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (co-operative agreement NU2GGH002022).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

JI, BC, RK, and AC conceptualized and designed the study. JI acquired the data. JI, BC, and AC analysed and interpreted the data. JI, BC, RK, and AC drafted the manuscript. BC, RK, and AC critically revised the manuscript. All authors (JI, BC, RK, and AC) approved the final manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate

This was a sub-analysis of data from a parent study. Ethical approval was obtained from the Infectious Diseases Institute Research Ethics Committee (#IDI-REC-2022-18) and the Uganda National Council for Science and Technology (#HS25553ES). Administrative clearance was from the Directorate of Public Health and Environment, KCCA (#DPHE/KCCA/1301).

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/. The Creative Commons Public Domain Dedication waiver (http://creativecommons.org/publicdomain/zero/1.0/) applies to the data made available in this article, unless otherwise stated in a credit line to the data.

About this article

Cite this article

Izudi, J., Castelnuovo, B., King, R. et al. Risk factors for unsuppressed viral load after intensive adherence counseling among HIV infected persons in Kampala, Uganda: a nested case–control study. AIDS Res Ther 20, 90 (2023). https://doi.org/10.1186/s12981-023-00583-3

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/s12981-023-00583-3