Abstract

Background

The availability of HIV antiretroviral therapy (ART) has been associated with the development of transmitted drug resistance-associated mutations (TDRM). TDRM can compromise treatment effectiveness in patients initiating ART and the prevalence can vary in different clinical settings. In this study, we investigated the proportion of TDRM in treatment-naïve, recently infected HIV-positive individuals sampled from four urban locations across Asia between 2007–2010.

Methods

Patients enrolled in the TREAT Asia Studies to Evaluate Resistance – Surveillance Study (TASER-S) were genotyped prior to ART initiation, with resulting resistance mutations analysed according to the WHO 2009 list.

Results

Proportions of TDRM from recently infected individuals from TASER-S ranged from 0% to 8.7% - Hong Kong: 3/88 (3.4%, 95% CI (0.71%-9.64%)); Thailand: Bangkok: 13/277 (4.7%, 95% CI (2.5%-7.9%)), Chiang Mai: 0/17 (0%, 97.5% CI (0%-19.5%)); and the Philippines: 6/69 (8.7%, 95% CI (3.3%-18.0%)). There was no significant increase in TDRM over time across all four clinical settings.

Conclusions

The observed proportion of TDRM in TASER-S patients from Hong Kong, Thailand and the Philippines was low to moderate during the study period. Regular monitoring of TDRM should be encouraged, especially with the scale-up of ART at higher CD4 levels.

Similar content being viewed by others

Background

Since 2001, the World Health Organization (WHO) has been promoting a public-health approach to improve access to antiretroviral therapy (ART) in resource-limited settings [1]. With the scale up of ART, patients who experienced virological failure or those who failed to suppress the virus may continue to have ongoing viral replication under drug pressure which increases the risk of the development of resistance-associated mutations (RAMs). These RAMs may further compromise future treatment outcomes and can be transmitted, leading to primary drug resistance in other un-treated individuals [2,3].

In resource-limited countries in Asia, non-nucleoside reverse transcriptase inhibitors (NNRTI) is predominantly used in standard first-line therapy. A Thai study reported a 2% prevalence of transmitted drug resistance-associated mutations (TDRM) in recently HIV-infected patients, with the annual proportion rising from 0% to 5.2% between 2003–2006. The most common RAMs found in this study were M184V and Y181C reflecting lamivudine and NNRTI resistance [4]. Hong Kong SAR China, a high-income locality, reported a TDRM prevalence of 3.6% between 2003–2007, with the protease inhibitors (PI) RAMs (M46I/L and L33F) being the most common mutations consistent with widespread use of PI-based initial regimen [5]. Conversely, an Australian study found rates of TDRM to have dropped dramatically after the introduction of combination ART in 1996 [6].

The objective of this study was to evaluate the extent of TDRM in treatment-naïve, recently infected HIV-positive individuals in selected Therapeutics, Research, Education, and AIDS Training in Asia (TREAT Asia) sites, and to determine changes in proportion of TDRM over time. The reported findings may not be representative of the broader Asia-Pacific region, but rather of those who participated in the study.

Methods

Treatment-naïve, recently HIV-infected patients were recruited into the TREAT Asia Studies to Evaluate Resistance – Surveillance Study (TASER-S) between 2007-2010 [7] from 5 participating sites: 2 from Hong Kong SAR, China; 1 from Bangkok, Thailand; 1 from Chiang Mai, Thailand; and 1 from Manila, Philippines. Patients were included in TASER-S according to the following inclusion criteria:

Hong Kong SAR, China: patients were selected from those who attended the two participating clinics and satisfied one of these criteria: (a) age up to 25 years old; (b) negative HIV test within one year; or (c) BED assay positive.

Bangkok, Thailand: patients were enrolled from a voluntary counselling and testing centre in Bangkok. All modes of HIV exposure were considered, however male patients with homosexual HIV exposure were selectively chosen to be enrolled in 2010. Recent HIV infection was defined as a new HIV diagnosis in subjects <25 years old. For those who were older, previous HIV-negative documentation within the past 12 months was required for study inclusion.

Chiang Mai, Thailand: patients presented to care at the participating hospital were selected for enrolment. Patients were included if they had a confirmed HIV-positive test and were aged <25 years with no prior AIDS-defining illnesses.

Manila, Philippines: blood samples were obtained from the STD AIDS Cooperative Central Laboratory, the National Reference Laboratory for HIV and Other STIs (NRL-SACCL). All samples obtained from asymptomatic patients were tested using the BED assay. Those with positive BED tests were presumed to be recently infected and included in TASER-S.

CD4 count was not used as a criteria in TASER-S as the study protocol was developed prior to the WHO 2008 surveillance recommendations [8], and it was not known a priori the time lag for obtaining CD4 results.

Genotyping was performed at TREAT Asia Quality Assessment Scheme (TAQAS) certified laboratories [9]. Pre-treatment pol gene FASTA files were submitted to the Stanford University HIV Drug Resistance Database [10] Version 6.2 for genotyping and REGA HIV-1 Subtyping Tool [11,12] - Version 2.0 for subtyping. RAMs were analysed according to the WHO 2009 list [13]. TDRM was defined as having ≥1 RAM. Patients with both protease (PR) and reverse transcriptase (RT) sequences available were included.

Clinical characteristics, including age, sex, mode of HIV exposure, viral load, CD4 count and HIV-1 subtype, were reported descriptively. Time trends were analysed using chi-squared test for trend. Confidence intervals (CI) for proportion of RAMs were calculated using the exact binomial methods. A sensitivity analysis was performed by including patients who were missing a PR or RT sequence file by assuming an absence of RAMs in the missing gene region and also by including those with extensive RAMs without confirmation of their treatment naïve status. All data management and statistical analyses were performed using SAS software version 9.3 (SAS Institute Inc., Cary, NC, USA) and STATA software version 12.1 (STATA Corp., College Station, TX, USA).

Data transfers were aggregated at The Kirby Institute, UNSW Australia. Ethics approvals were obtained from UNSW Australia Ethics Committee and institutional review boards at the participating clinical sites and coordinating centre (TREAT Asia/amfAR, Bangkok, Thailand). Written informed consent was obtained from participants prior to enrolment – except in the Philippines, where anonymous samples were obtained from the NRL-SACCL and consent was waived.

Results

Hong Kong SAR, China

A total of 88 patients were included from the 2 sites (Table 1). The overall proportion was 3/88 (3.4%, 95% CI (0.71%-9.64%)). Figure 1 shows TDRM in 2007 was 0/28 (0.0%); 2008: 2/32 (6.3%); 2009: 1/21 (4.8%); and 2010: 0/7 (0.0%), p-trend = 0.631.

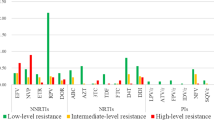

Table 2 shows a list of RAMs harboured by different individuals. Of the 3 patients with RAMs from Hong Kong, 1 patient had a PR RAM (M46I) and 2 patients had one RT RAM each (K103N and M41L).

Bangkok, Thailand

Recruitment occurred between 2008–2010 with a total of 277 patients. TDRM was present in 13/277 (4.7%, 95% CI (2.5%-7.9%)). The proportions of TDRM by year were: 2008: 4/118 (3.4%); 2009: 4/83 (4.8%); and 2010: 5/76 (6.6%), p-trend = 0.305 (Figure 1). The most common PR-RAM was M46I (6 patients) and the most common RT-RAM was Y181C (3 patients) (Table 2).

Chiang Mai, Thailand

Seventeen patients were enrolled into the study during the years 2007 (4 patients), 2008 (10 patients) and 2009 (3 patients). No patient harboured RAMs, with 97.5% one-sided CI of (0%-19.5%).

Manila, Philippines

Blood samples were collected from 69 patients. TDRM was present in 6/69 patients (8.7%, 95% CI (3.3%-18.0%)). Figure 1 shows in 2008, 0/1 patients (0.0%) had TDRM; 2009: 6/67 (9.0%); and 2010: 0/1 (0.0%), p-trend >0.999.

Out of the 6 patients who harboured RAMs, all but one harboured only one resistance mutation (Table 2).

Sensitivity analysis

With the inclusion of 5 patients with missing RT region and 3 patients with extensive mutations from Bangkok, the total proportion of TDRM for this site increased to 5.6% with 95% CI (3.2%-9.0%). The yearly trend of TDRM was not significant at p = 0.256. For Manila, the inclusion of 13 patients with missing PR or RT sequences increased the proportion to 7/82 (8.5%, 95% CI (3.5%-16.8%)), p-trend = 0.860.

Discussion

Observed proportions of TDRM in this study ranged from 0% to 8.7%, with no significant increase in trend over time. TASER-S participants were predominantly men who have sex with men (MSM). Studies have shown that MSM was associated with the presence of TDRM with higher rates of resistance reported in this group [5,14]. Although each TASER-S site utilised a different recruitment strategy which prevents direct comparison of TDRM across sites, the findings of this study suggests that the Philippines, a country that has not yet encountered a national epidemic comparable to other Southeast Asian countries [15], had a relatively higher TDRM proportion of 8.7%. This could be due to other non-B subtypes [16] prevalent in the sample (26.1%) and may warrant further investigation into the extent of HIV RAMs within the country and the associated key population at risk.

The proportion of TDRM for Hong Kong (3.4%) and Bangkok (4.7%) were similar to that found previously [5,17] although there were differences in the sample sizes and sampling methodology. Chiang Mai reported 0% TDRM, but given that only 17 patients were enrolled, it is not possible to exclude drug resistance prevalence as high as 19.5%.

Our study had several limitations including the potential sampling bias within the study. TASER-S included only patients attending TREAT Asia sites. Informed consent was required from all participants, except in the Philippines, and this may further contribute to sampling bias by allowing only those who consented to be included in the study. Other limitations were the possibility of patients experiencing reversion of RAMs back to wild-type [18,19]; and the possibility of misclassification by BED assay due to its high false recent rates [20], although this only applies to patients recruited from Hong Kong and the Philippines. Findings of TDRM reported in this study only reflect those participating in TASER-S and may not be generalisable to the broader HIV-infected population across the region.

Conclusions

In summary, the observed proportion of TDRM in TASER-S patients from Hong Kong, Thailand and the Philippines was low to moderate during the study period. With the 2013 WHO guidelines recommending ART initiation in persons with CD4 count ≤500 cells/μL [21], and the possible scale-up of ART due to “Test and Treat” strategies [22], further monitoring of acquired drug resistance in individuals on ART, as well as regular surveillance of recently infected persons should be encouraged.

References

World Health Organization. Antiretroviral therapy for HIV infection in adults and adolescents. Recommendations for a public health approach: 2010 revision. [http://www.who.int/hiv/pub/arv/adult2010/en/index.html]

Lima VD, Harrigan PR, Senecal M, Yip B, Druyts E, Hogg RS, et al. Epidemiology of antiretroviral multiclass resistance. Am J Epidemiol. 2010;172:460–8.

Drug Resistance. [http://aids.gov/hiv-aids-basics/just-diagnosed-with-hiv-aids/treatment-options/drug-resistance/]

Apisarnthanarak A, Jirayasethpong T, Sa-nguansilp C, Thongprapai H, Kittihanukul C, Kamudamas A, et al. Antiretroviral drug resistance among antiretroviral-naive persons with recent HIV infection in Thailand. HIV Med. 2008;9:322–5.

Wong KH, Chan WK, Yam WC, Chen JH, Alvarez-Bognar FR, Chan KC. Stable and low prevalence of transmitted HIV type 1 drug resistance despite two decades of antiretroviral therapy in Hong Kong. AIDS Res Hum Retroviruses. 2010;26:1079–85.

Ammaranond P, Cunningham P, Oelrichs R, Suzuki K, Harris C, Leas L, et al. No increase in protease resistance and a decrease in reverse transcriptase resistance mutations in primary HIV-1 infection: 1992–2001. AIDS. 2003;17:264–7.

Kiertiburanakul S, Chaiwarith R, Sirivichayakul S, Ditangco R, Jiamsakul A, Li PC, et al. Comparisons of Primary HIV-1 Drug Resistance between Recent and Chronic HIV-1 Infection within a Sub-Regional Cohort of Asian Patients. PLoS One. 2013;8:e62057.

Bennett DE, Myatt M, Bertagnolio S, Sutherland D, Gilks CF. Recommendations for surveillance of transmitted HIV drug resistance in countries scaling up antiretroviral treatment. Antivir Ther. 2008;13 Suppl 2:25–36.

Land S, Zhou J, Cunningham P, Sohn AH, Singtoroj T, Katzenstein D, et al. Capacity building and predictors of success for HIV-1 drug resistance testing in the Asia-Pacific region and Africa. J Int AIDS Soc. 2013;16:18580.

Liu TF, Shafer RW. Web resources for HIV type 1 genotypic-resistance test interpretation. Clin Infect Dis. 2006;42:1608–18.

de Oliveira T, Deforche K, Cassol S, Salminen M, Paraskevis D, Seebregts C, et al. An automated genotyping system for analysis of HIV-1 and other microbial sequences. Bioinformatics. 2005;21:3797–800.

Alcantara LC, Cassol S, Libin P, Deforche K, Pybus OG, Van Ranst M, et al. A standardized framework for accurate, high-throughput genotyping of recombinant and non-recombinant viral sequences. Nucleic Acids Res. 2009;37:W634–42.

Bennett DE, Camacho RJ, Otelea D, Kuritzkes DR, Fleury H, Kiuchi M, et al. Drug resistance mutations for surveillance of transmitted HIV-1 drug-resistance: 2009 update. PLoS One. 2009;4:e4724.

Sohn AH, Srikantiah P, Sungkanuparph S, Zhang F. Transmitted HIV drug resistance in Asia. Curr Opin HIV AIDS. 2013;8:27–33.

Farr AC, Wilson DP. An HIV epidemic is ready to emerge in the Philippines. J Int AIDS Soc. 2010;13:16.

Lessells RJ, Katzenstein DK, de Oliveira T. Are subtype differences important in HIV drug resistance? Current opinion in virology. 2012;2:636–43.

Sungkanuparph S, Pasomsub E, Chantratita W. Surveillance of Transmitted HIV Drug Resistance in Antiretroviral-Naive Patients Aged less than 25 Years, in Bangkok, Thailand. Journal of the International Association of Providers of AIDS Care. 2014;13:12–4.

Jain V, Sucupira MC, Bacchetti P, Hartogensis W, Diaz RS, Kallas EG, et al. Differential persistence of transmitted HIV-1 drug resistance mutation classes. J Infect Dis. 2011;203:1174–81.

Boettiger DC, Kiertiburanakul S, Sungkanuparph S, Law MG. Resistance TAStE. The impact of wild-type reversion on transmitted resistance surveillance. Antivir Ther. 2014;19(7):719–22.

Incidence Assay Critical Path Working G. More and better information to tackle HIV epidemics: towards improved HIV incidence assays. PLoS Med. 2011;8:e1001045.

World Health Organization. Consolidated guidelines on the use of antiretroviral drugs for treatment and preventing HIV infection: Recommendations for a public health approach June 2013. [http://apps.who.int/iris/bitstream/10665/85321/1/9789241505727_eng.pdf]

Granich RM, Gilks CF, Dye C, De Cock KM, Williams BG. Universal voluntary HIV testing with immediate antiretroviral therapy as a strategy for elimination of HIV transmission: a mathematical model. Lancet. 2009;373:48–57.

Acknowledgements

The TREAT Asia Studies to Evaluate Resistance (TASER) is an initiative of TREAT Asia, a program of amfAR, The Foundation for AIDS Research, with major support provided by the Dutch Ministry of Foreign Affairs through a partnership with Stichting Aids Fonds, and with additional support from amfAR and the National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases (NIAID) of the U.S. National Institutes of Health (NIH) and the National Cancer Institute (NCI) as part of the International Epidemiologic Databases to Evaluate AIDS (IeDEA) (grant no. U01AI069907). Queen Elizabeth Hospital and the Integrated Treatment Centre are supported by the Hong Kong Council for AIDS Trust Fund. The Kirby Institute is funded by the Australian Government Department of Health and Ageing, and is affiliated with the Faculty of Medicine, UNSW Australia (the University of New South Wales). The content of this publication is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of any of the governments or institutions mentioned above.

Members of the TASER study

• PCK Li*¶ and MP Lee, Queen Elizabeth Hospital and KH Wong, Integrated Treatment Centre, Hong Kong, China;

• N Kumarasamy*§ and S Saghayam, YRGCARE Medical Centre, Chennai, India;

• S Pujari* and K Joshi, Institute of Infectious Diseases, Pune, India;

• TP Merati* and F Yuliana, Faculty of Medicine, Udayana University & Sanglah Hospital, Bali, Indonesia;

• CKC Lee* and BLH Sim, Hospital Sungai Buloh, Kuala Lumpur, Malaysia;

• A Kamarulzaman*¶ and LY Ong, University of Malaya, Kuala Lumpur, Malaysia;

• M Mustafa* and N Nordin, Hospital Raja Perempuan Zainab II, Kota Bharu, Malaysia;

• R Ditangco*† and RO Bantique, Research Institute for Tropical Medicine, Manila, Philippines;

• YMA Chen*§ and YT Lin, Kaohsiung Medical University, Kaohsiung City, Taiwan;

• P Phanuphak* and S Sirivichayakul, HIV-NAT/Thai Red Cross AIDS Research Centre, Bangkok, Thailand;

• S Sungkanuparph*, S Kiertiburanakul, and L Chumla, Faculty of Medicine Ramathibodi Hospital, Mahidol University, Bangkok, Thailand;

• T Sirisanthana* and J Praparattanapan, Research Institute for Health Sciences, Chiang Mai University, Chiang Mai, Thailand;

• P Kantipong* and P Kambua, Chiangrai Prachanukroh Hospital, Chiang Rai, Thailand;

• W Ratanasuwan* and R Sriondee, Faculty of Medicine Siriraj Hospital, Mahidol University, Bangkok, Thailand;

• R Kantor*, Brown University, Rhode Island, U.S.A.;

• AH Sohn, N Durier* and T Singtoroj, TREAT Asia, amfAR – The Foundation for AIDS Research, Bangkok, Thailand;

• DA Cooper, MG Law*, A Jiamsakul, and DC Boettiger, The Kirby Institute, UNSW Australia, Sydney, Australia.

* TASER Steering Committee member

† Steering Committee Chair

§ Protocol Chair

¶ Protocol Co-Chair

Genbank accession numbers

The accession numbers for the sequences used in this analysis are as follows:

KC810534-KC810543, KC810549, KC810558, KC810566, KC810785-KC810794, KC810800, KC810809, KC810817, KC921485-KC921766, KC961260, KC994316-KC994341, KC994397-KC994450, KF059650-KF059717, KF059755-KF059833, KM065804-KM065831.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Consortia

Corresponding author

Additional information

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Authors’ contributions

AJ performed data management, statistical analysis, drafting and submission of the final manuscript. ML originated concept ideas, reviewed the analysis plan and provided revisions to the manuscript. JP edited FASTA files for Genbank submission. SS, RD, KW, PL, PP, EM, WY, TS, and TS have provided revision to the manuscript. All authors have read and approved the final manuscript.

Rights and permissions

This article is published under an open access license. Please check the 'Copyright Information' section either on this page or in the PDF for details of this license and what re-use is permitted. If your intended use exceeds what is permitted by the license or if you are unable to locate the licence and re-use information, please contact the Rights and Permissions team.

About this article

Cite this article

Jiamsakul, A., Sirivichayakul, S., Ditangco, R. et al. Transmitted drug resistance in recently infected HIV-positive Individuals from four urban locations across Asia (2007–2010) – TASER-S. AIDS Res Ther 12, 3 (2015). https://doi.org/10.1186/s12981-015-0043-1

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/s12981-015-0043-1