Abstract

Menopause nomenclature varies in the scholarly literature making synthesis and interpretation of research findings difficult. Therefore, the present study aimed to review and discuss critical developments in menopause nomenclature; determine the level of heterogeneity amongst menopause definitions and compare them with the Stages of Reproductive Aging Workshop criteria. Definitions/criteria used to characterise premenopausal and postmenopausal status were extracted from 210 studies and 128 of these studies were included in the final analyses. The main findings were that 39.84% of included studies were consistent with STRAW classification of premenopause, whereas 70.31% were consistent with STRAW classification of postmenopause. Surprisingly, major inconsistencies relating to premenopause definition were due to a total lack of reporting of any definitions/criteria for premenopause (39.84% of studies). In contrast, only 20.31% did not report definitions/criteria for postmenopause. The present findings indicate that there is a significant amount of heterogeneity associated with the definition of premenopause, compared with postmenopause. We propose three key suggestions/recommendations, which can be distilled from these findings. Firstly, premenopause should be transparently operationalised and reported. Secondly, as a minimum requirement, regular menstruation should be defined as the number of menstrual cycles in a period of at least 3 months. Finally, the utility of introducing normative age-ranges as supplementary criterion for defining stages of reproductive ageing should be considered. The use of consistent terminology in research will enhance our capacity to compare results from different studies and more effectively investigate issues related to women’s health and ageing.

Plain Language Summary

The meaning of menopause is widely understood, but often imprecisely defined in research. The present findings revealed that there is a significant amount of heterogeneity associated with the definition of premenopause, compared with postmenopause. Three key suggestions/recommendations can be distilled from these findings. Firstly, premenopause should be transparently operationalised and reported. Secondly, as a minimum requirement, regular menstruation should be defined as the number of menstrual cycles in a period of at least 3 months. Finally, the utility of introducing normative age-ranges as supplementary criterion for defining stages of reproductive ageing should be considered. The use of consistent terminology in research will enhance our capacity to compare results from different studies and more effectively investigate issues related to women’s health and ageing.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

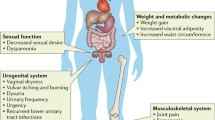

Menopause is a critical stage of female reproductive ageing and health, with important implications relating to fat mass and its distribution [1], dyslipidemia [2] and neurodegeneration [3, 4]. In this context, it is likely that some of the biological changes co-occurring with menopause, contribute to the well-documented higher risk of dementia in women [5], as well as the observed increase in cardiovascular disease whose pattern becomes more similar to that of men at older ages despite its lower prevalence at younger ages [6, 7]. However, the contributions of menopause to health have been historically understudied in the context of ageing [8]. For example, over a period of 23 years (1995–2017), peer-reviewed neuroimaging articles which focused on menopause only accounted for approximately 2% of the ageing literature [8]. There are many possible explanations (including sex biases in research), however, a critical challenge for menopause research has been the operationalisation of menopause nomenclature.

The meaning of menopause is widely understood, but often imprecisely defined in research. The standards for defining menopause nomenclature, such as premenopause and postmenopause vary substantially across publications. Although, the precise extent of this heterogeneity remains to be established—perhaps because the extant literature on this topic may be too large to systematically review—it is clear that such variability across studies makes the synthesis and comparison of findings difficult. In recognition of this issue, there have been a number of attempts by international experts to collaboratively develop a comprehensive standardised set of criteria to describe terminology associated with menopause [9,10,11,12,13,14]. Whilst promising developments have been made in recent decades, a follow-up investigation regarding the frequency and consistency of uptake and use of the proposed criteria have not been adequately investigated. Therefore, the degree to which standardised criteria have been successfully implemented in publications relating to menopause research remains unknown.

To address this gap we have leveraged on our recent systematic review with meta-analysis focused on fat mass differences between premenopausal and postmenopausal women, which included 210 studies consisting of 1,052,391 women, by extracting definitions used to characterise premenopausal and postmenopausal status in a broad cross-section of peer-reviewed literature [1]. The present study aims to first review and discuss critical developments in menopause nomenclature, with a particular emphasis placed on the implications that current criteria have for menopause research. Then, to assess the level of heterogeneity in menopause nomenclature identified through our previous systematic review [7]. Finally, to contrast the extracted definitions against the Stages of Reproductive Aging Workshop (STRAW) criteria [11, 13, 14].

WHO (1981–1999)

According to the more recently established guidelines by a World Health Organization (WHO) “Scientific Group on Research in the Menopause”, natural menopause is defined as the permanent cessation of menstruation resulting from the loss of ovarian follicular activity [9, 10]. Furthermore, natural menopause is deemed to have occurred after 12 consecutive months of amenorrhea, for which no other obvious pathological or physiological causes could be determined. As seen in Fig. 1, menopause occurs at the final menstrual period (FMP), which can only be known with certainty retrospectively, a year or more after the event. Induced menopause, however, is defined as the cessation of menstruation following either surgical removal of both ovaries (i.e. oophorectomy), or iatrogenic ablation of ovarian function (i.e. chemotherapy or irradiation).

Visual representation of the relationship between different time periods surrounding menopause as established by a World Health Organization Scientific Group on Research in the Menopause. Figure is a modification of work found in World Health Organization [9]

The WHO (1996) highlighted that premenopause was often used ambiguously by researchers, either to refer to the 1 or 2 years immediately before menopause or alternatively, to encompass the entire reproductive period up to the FMP, which was the recommended use of the term. Other critical stages defined by the WHO included postmenopause (i.e. the period following the FMP regardless of whether menopause was induced or spontaneous); perimenopause (i.e. the period immediately prior to the FMP when endocrinological, biological and clinical features of approaching menopause commence, as well as the first year after menopause); and the menopausal transition (i.e. the period of time before FMP, when variability in the menstrual cycle is usually increased). Finally, it was strongly recommended that the term climacteric, which was previously used interchangeably with perimenopause, should be abandoned to avoid confusion. However, due to widespread popularity and the prevailing use of the word, climacteric was reinstated by The Council of Affiliated Menopause Societies (CAMS) in 1999 and was defined as a phase which incorporates perimenopause, but extends for a longer variable period before and after perimenopause and marks the transition from the reproductive to non-reproductive states (Fig. 2) [13].

Updated visual representation of the relationship between different time periods surrounding menopause, which includes the term Climacteric as defined by The Council of Affiliated Menopause Societies. Figure is a modification of work found in Utian [13]

STRAW (2001)

The nomenclature established thus far facilitated a scientific consensus for describing female reproductive ageing, however, there were still limitations that needed to be addressed. For example, the WHO and CAMS definitions had vague starting points and used terms such as premenopause, perimenopause, menopausal transition and climacteric which, to some extent, had overlapping time periods. This lack of clear, objective criteria to describe the stages of female reproductive ageing led to the Stages of Reproductive Ageing Workshop (STRAW) in 2001. The ensuing STRAW criteria separated the stages of female reproductive ageing into seven distinct segments (Fig. 3), with a particular focus on healthy women undergoing natural menopause. Furthermore, menstrual cycles, endocrine/biochemical factors, signs/symptoms in other organ systems, and uterine/ovarian anatomy were used to define the stages of female reproductive ageing.

STRAW staging system. *Stages most likely to be characterised by vasomotor symptoms; FSH, follicle stimulating hormone; ↑, elevated. Figure is a modification of work found in Soules et al. [14]

Within the STRAW criteria, menopause is central to the staging system and was labelled as point zero (0). There are five stages preceding the FMP (− 5 to − 1) and two following it (+ 1 to + 2). Stages − 5 to − 3 encompassed the Reproductive Interval; − 2 to − 1 reflected the Menopausal Transition; and + 1 to + 2 defined Postmenopause [14]. The menopausal transition (− 2 to − 1) began with a variation in menstrual cycle length and rise in follicle stimulating hormone (FSH) and ended with the FMP. Early postmenopause (+ 1) was defined as within 5 years since the FMP and was further subdivided into segments ‘a’; the first 12 months after the FMP and ‘b’; the following 4 years. Whereas late postmenopause (+ 2) was defined as having a variable duration since it ended with a woman’s death. Finally, the STRAW criteria defined perimenopause (− 2 to + 1a) as ending 12 months after the FMP. Furthermore, it was suggested that the terms perimenopause and climacteric should be synonymous in meaning and used with patients or the public, but not in scientific papers, in accordance with the WHO recommendations.

Importantly, the validity and reliability of the STRAW recommendations has been evaluated and was broadly supported by the ReSTAGE Collaboration, which conducted empirical analyses on four cohort studies including the TREMIN study, the Seattle Midlife Women’s Health Study, the Study of Women’s Health Across the Nation (SWAN) and the Melbourne Women’s Midlife Health Project [12, 15, 16]. However, particular limitations have also been noted and modifications to the STRAW criteria were suggested by the ReSTAGE collaboration. In particular, when the STRAW criteria were first established, there was a lack of multiethnic cohort studies available, which limited the generalisability of the staging system to diverse populations [11]. Furthermore, the initial STRAW criteria only considered FSH as a biomarker, with relatively little clarification about the precise timing of change in FSH levels or quantitative criteria for FSH, due to insufficient data [11]. As a result, the initial STRAW criteria focused primarily on menstrual bleeding patterns and qualitative FSH levels. Other important limitations of the original STRAW criteria included their exclusive applicability to healthy women, with explicit recommendations against applying the criteria to women who either (i) smoked, (ii) had a BMI greater than 30 \(\mathrm{kg}/{\mathrm{m}}^{2}\) or less than 18 \(\mathrm{kg}/{\mathrm{m}}^{2}\), (iii) engaged in heavy exercise (greater than 10 h per week of aerobic exercise), (iv) had chronic menstrual cycle irregularity, (v) had a prior hysterectomy, (vi) had abnormal uterine anatomy (e.g. fibroids) or (vii) had abnormal ovarian anatomy (e.g. endometrioma).

STRAW + 10 (2011)

In 2011, the STRAW + 10 criteria [11] were established to reflect significant advances in the field of female reproductive ageing and to provide updated recommendations that addressed certain limitations present in the initial staging criteria.

The STRAW + 10 staging system suggested that the late reproductive stage (− 3) should be subdivided into two stages (− 3b and − 3a) based on menstrual cycle characteristics and FSH levels (Fig. 4). This was done to recognise subtle changes in menstrual cycle flow and also shorter cycle lengths in stage − 3a, in addition to an increased variability in FSH levels [11]. Secondly, the new recommendations incorporated the suggestions provided by the ReSTAGE Collaboration, which proposed that more precise menstrual cycle criteria should be used to describe the early (− 2) and late (− 1) menopausal transition, in addition to the quantification of FSH levels in late menopausal transition [4]. Specifically, the early menopausal transition (− 2) was discernible from the late reproductive stage (− 3a) due to an increased variability in menstrual cycle length (defined as a difference of 7 days or more in length of a menstrual cycle that is persistent i.e. reoccurs within 10 cycles of the first variable length cycle). Furthermore, late menopausal transition (− 1) was marked by an interval of amenorrhea greater or equal to 60 days, in addition to an increased FSH level greater than 25 IU/L [11, 12]. Finally, early postmenopause (+ 1) was further subdivided into three stages (+ 1a, + 1b, + 1c) to account for the continual increase in FSH and decrease in estradiol for 2 years after FMP, whereby + 1a corresponded with 12 months after FMP i.e. end of perimenopause and + 1b referred to the year prior to the stabilisation of high FSH and low estradiol levels (+ 1c).

STRAW + 10 staging system. *, blood drawn on cycle days 2–5; FSH, follicle stimulating hormone; AMH, anti-mullerian hormone; ↑, elevated. Figure is a modification of work found in Harlow et al. [11]

The STRAW + 10 staging system has been found to be applicable to most women regardless of age, demographic, body mass index (BMI) or lifestyle characteristics [11]. However there are still significant areas of scientific research that need to be prioritised to strengthen future criteria including (i) the use of standardised assays for key biomarkers (e.g. Anti-Mullerian hormone), (ii) further empirical analysis across multiple cohorts to specify menstrual cycle criteria for the late reproductive stage, and (iii) further research aimed at better understanding reproductive ageing in women who have had either the removal of a single ovary and/or a hysterectomy, chronic illness such as HIV infection, cancer treatment, polycystic ovary syndrome or premature ovarian failure [11]. Another critical limitation of the STRAW + 10 criteria is that they do not apply to women who are using exogenous hormones, such as hormone replacement therapy (HRT). Likely because HRT use may confound the accurate classification of women into distinct reproductive stages. This is a key consideration that needs to be appropriately accounted for in studies that are interested in investigating varying outcomes in women at different stages of reproductive ageing.

Despite these limitations, the STRAW criteria has significantly advanced our understanding of women’s health and is widely considered the current gold standard for defining terms related to female reproductive ageing. However, the uptake and use of the STRAW criteria in publications relating to menopause research remains unknown and is addressed next.

Methods

The definitions of premenopausal and postmenopausal women were extracted from the 210 studies (Additional file 1: Table 1, Additional file 2: Table 2) [17–134, 134,135,136,137,138,139,140,141,142,143,144,145,146,147,148,149,150,151,152,153,154,155,156,157,158,159,160,161,162,163,164,165,166,167,168, 168,169,170,171,172,173,174,175,176,177,178,179,180,181,182,183,184,185,186,187,188,189,190,191,192,193,194,195,196,197,198,199,200,201,202,203,204,205,206,207,208,209,210,211,212,213,214,215,216,217,218,219,220,221,222,223,224,225, 236] that were eligible for inclusion in the meta-analysis from a previous systematic review, which aimed to identify all peer-reviewed articles reporting on changes in fat mass around menopause [1]. Given that the focus of the present study is the relationship between definitions used in the current literature and the STRAW criteria, only studies published 4 years after the establishment of the STRAW criteria in 2001 (i.e. 2005 onwards) have been included in the analysis. The 4-year lag time was implemented to conservatively account for the ‘study inception to publication’ timeframe, which may have limited the ability for certain studies published between 2001 and 2005 to effectively implement the STRAW criteria. Similarly, longitudinal studies, which had baseline assessments prior to 2005, were excluded. Therefore, 128 studies were included in the final analyses.

Protocol and registration

The methodology of the initial meta-analyses is reported elsewhere in detail [1] and was pre-registered in the PROSPERO database (CRD42018100643), which can be accessed online (http://www.crd.york.ac.uk/PROSPERO/display_record.php?ID=CRD42018100643).

Search string

The PubMed database was used to conduct a systematic search and retrieve all studies that reported fat mass differences in quantity or distribution between premenopausal and postmenopausal women. The following search string was used: (“adipose tissue” OR “adiposity” OR “subcutaneous fat” OR “obesity” OR “overweight” OR “body weight” OR “body fat distribution” OR “body mass index” OR “BMI” OR “DEXA” OR “DXA” OR “dual energy x-ray absorptiometry” OR “waist to hip ratio” OR “waist-hip ratio” OR “waist circumference” OR “x-ray computed tomography” OR “computed tomography” OR “CT scan” OR “caliper” OR “skinfold” OR “skin fold” OR “abdominal MRI” OR “abdominal magnetic resonance imaging” OR “intra-abdominal fat”) AND (“menarche” OR “pre-menopause” OR “premenopause” OR “pre-menopausal” OR “premenopausal” OR “reproductive” OR “menopausal transition”) AND (“post-menopause” OR “postmenopause” OR “post-menopausal” OR “postmenopausal” OR “non-reproductive”). PubMed filters were used to exclude non-human and non-English studies. No time restrictions were applied to the literature search, which was conducted in May 2018.

Inclusion and exclusion criteria

Studies that investigated both healthy premenopausal and healthy postmenopausal women were included, whereas studies that (i) exclusively investigated clinical/pathophysiological populations or (ii) had fewer than 40 participants were excluded.

Data extraction

Available definitions/criteria used to describe premenopausal and postmenopausal women were extracted from each study. Where data was missing or unclear, authors were contacted via email to obtain relevant information. All data from included articles was double extracted by two authors (AA and EW) to avoid transcription errors with any disagreement resolved by consensus.

Quality assessment

The quality of included studies was independently assessed by two authors (AA and EW), using an adapted version of the Newcastle–Ottawa Scale (NOS) [226]. More information on the quality of included studies can be found in our recent systematic review with meta-analysis [1]. In short, the NOS for cohort studies utilised three categories to evaluate individual study quality including (1) the selection of participants, (2) the comparability of groups and (3) the assessment/ascertainment of the outcome of interest. Notably, a clear definition of premenopausal and postmenopausal women was included as a criterion when assessing study quality, specifically for the comparability of groups. Any discrepancy in quality assessment was resolved by consensus. If consensus decisions were not possible a third rater was used.

Results

The raw extracted definitions for studies are presented in Additional file 1: Table 1 and Additional file 2: Table 2. The consistency of definitions with STRAW criteria for included studies is presented in Fig. 5.

Premenopausal women

Cycle regularity

A total of 41 studies included the criterion regular menstruation, three included regular menstruation in the last 5 years, 1 included regular menstruation in the past 2 years and 1 included regular menstruation in the past year. Therefore, 46 studies (35.94%) were consistent with STRAW classification of premenopause, based on menstrual cycles.

Two studies used still cycling, 2 used no increase in cycle irregularity and 2 used no change in flow when characterising premenopausal women. Cycle regularity was further quantified by the use of cycles per month(s) or cycles per year(s). Three studies included the criteria one menstruation in the past 33 days, 2 included two menstruations in the last 3 months, 1 included at least one menstruation in the last 3 months, 1 included 11–13 cycles per year, 1 included 8 menses in the last year, 2 included one menstrual cycle in the last 12 months and 1 included one menstrual cycle in the last 2 years. One study identified premenopause as the whole reproductive period up until menopause.

Hormone levels

Six studies 4.69% used FSH levels as one of the criteria, consistent with STRAW classification of premenopause, based on hormone levels. Of these 6 studies, 1 used regular menstruation as an additional criterion, whereas the other 5 attempted to quantify cycle regularity. The threshold for FSH levels ranged from less than 20 IU/L to less than 40 IU/L.

Age

Four studies included women over a specific age ranging from 40 to 44. However all 4 studies also included other subcategories such as regular menstruation. Two studies used age brackets that included 25–45, and 45–55. Ten studies included women who were less than a specific age, which ranged from 35 to 55 years. Of these 3 studies used age as the only criterion to define premenopause. One study included age as a subcategory of their definition, however, did not define it precisely.

Not postmenopausal or pregnant

Five studies included no criteria for postmenopause, 4 included no symptoms of menopause, 4 included no climacteric complaints, 3 included no HRT use and 3 included no hysterectomy or ovaries removed as criteria for categorising premenopause. One study used pregnancy as a criterion for defining premenopause.

No definition

Of the 128 studies included, 51 (39.84%) did not report definitions/criteria for premenopause.

Postmenopausal women

Amenorrhea or the final menstrual period (FMP)

Eighty studies included the criterion at least 12 months of amenorrhea, 1 included less than 2 years from the FMP, 1 included 1–5 years since the FMP, 1 included 0–6 years after the FMP, 1 included greater than 1 but less than 7 years of amenorrhea, 1 included greater than 2 but less than 7 years amenorrhea and 2 included 2 years after the FMP. Therefore, 87 studies (67.97%) were consistent with STRAW classification of postmenopause, based on menstrual cycles.

Two studies included at least 6 months of amenorrhea and 1 included at least 11 months of amenorrhea. Three studies included the term no menstrual cycles or periods or no menstrual bleeding however, further detail regarding the duration of amenorrhea was not provided.

Hormone levels

Fourteen studies (10.94%) used FSH levels as a criterion, consistent with STRAW classification of postmenopause, based on hormone levels. Of these 11 studies used menstrual criteria consistent with STRAW, 2 used hormonal criterion alone and 1 included no menstrual bleeding. For hormone thresholds, of the 14 studies, 8 used the threshold for FSH levels as greater than 30 IU/L and 2 used greater than 40 IU/L. One study did not report FSH thresholds, whereas the remaining 3 studies had FSH levels that included greater than 20 IU/L, greater than 55 IU/L and between 22 to 138 IU/L. Two studies used estradiol levels with thresholds ranging from less than 20 pg/mL to less than 50 pg/mL. One study also used Luteinizing Hormone (LH) levels greater than 30 IU/L.

Natural or surgical menopause

Twelve studies specifically stated natural menopause, 3 stated no surgical removal of ovaries and/or uterus and 2 stated not due to surgery or any other biological or physiological causes. Twelve studies included the criteria bilateral oophorectomy, 2 included hysterectomy and 1 included cessation of menses induced by surgery.

Age

Twelve studies included women over a specific age, ranging from 40 to 55. Of these 2 studies used age as the only criterion to define postmenopausal women.

Hormone replacement therapy (HRT)

Five studies included women not taking HRT, whereas 4 studies included women taking HRT, and 1 study included women taking ovarian suppressing drugs or contraception eliminating menstruation.

No definition

Of the 128 studies included, 26 (20.31%) did not report any definitions/criteria for postmenopause.

Discussion

To our knowledge, this review is the first to assess the uptake and use of the STRAW criteria by extracting definitions used to characterise premenopausal and postmenopausal status in a broad cross-section of peer-reviewed literature from our recent systematic review with meta-analysis [1]. The main findings were that 39.84% of included studies were consistent with STRAW classification of premenopause, whereas 70.31% were consistent with STRAW classification of postmenopause (Fig. 5). Furthermore, 39.84% did not report definitions/criteria for premenopausal women, whereas, 20.31% did not report definitions/criteria for postmenopausal women.

For menstrual cycle variability, 35.94% of studies were consistent with STRAW classification of premenopause and 67.97% for postmenopause. Notably, STRAW + 10 later distinguished menstrual cycle variability as the most important criteria for the reproductive staging system [11], which is reflective of its use in the literature. For postmenopause, the current results reflect a conceptualisation consistent with the STRAW criteria, which require the relationship between the FMP and start of postmenopause to be explicitly defined. However, this same level of consistency was not observed for premenopause. One possible explanation relates to the term premenopause not having been explicitly used in the STRAW criteria [11, 14]. Instead, it is inferred to be synonymous with reproductive stage. Given its wide clinical and scientific use, our recommendation is that the transparent operationalisation of premenopause may improve the consistency and application of the STRAW criteria (Fig. 6). Another possibility is the degree of uncertainty regarding the precise meaning of regular menstruation. Specifically, 14.29% of studies that defined premenopause attempted to quantify regular menstruation as the number of menstrual cycles per days, month(s) or year(s). This uncertainty may reflect a key limitation of the STRAW [14] and more recent STRAW + 10 [11] criteria, which principally describe the reproductive period as having regular menstrual cycles, with no guidelines provided regarding the interpretation of regular. Moreover, previous research has demonstrated the lack of clear clinical definitions for reproductive stages can significantly decrease the accuracy of participant’s self-report [227]. Since menstrual cycles can be skipped due to reasons unrelated to menopause including extreme exercise, pregnancy, weight fluctuations or illness it would be highly preferable if regular menstruation was specifically and consistently defined for a defined period. We recommend that defining regular menstruation as the number of menstrual cycles per 3 months, as a minimum requirement, would be a practical reporting timeframe both clinically and for women to recall accurately (Fig. 6).

Recommended revision to the STRAW + 10 staging system to include the transparent operationalisation of premenopause and define regular menstruation as the number of menstrual cycles per 3 months, as a minimum requirement, which would be a practical reporting timeframe both clinically and for women to recall accurately. *, blood drawn on cycle days 2–5; FSH, follicle stimulating hormone; AMH, anti-mullerian hormone; ↑, elevated. Figure is a modification of work found in Harlow et al. [11]

For hormone levels, 4.69% of studies were consistent with STRAW classification of premenopause and 10.94% for postmenopause. STRAW + 10 later distinguished hormone levels as a supportive criterion for the reproductive staging system given the lack of international standardisation of biomarker assays as well as their cost and/or invasiveness and inequity across low-socioeconomic countries [11]. Notably, Anti-Mullerian hormone (AMH) has emerged as a primary candidate for developing an international standard biomarker since it is detectable in peripheral circulation [228] and does not change in response to an acute endogenous rise in hormones such as FSH and estrogen [229,230,231]. Whilst promising, insights about staging reproductive ageing can also be drawn from research that aims to predict age of menopause. Unsurprisingly, age is a useful predictor of menopausal status [232], given ageing and menopause co-occur [233]. However, evidence suggests that the combination of hormones, such as AMH and age does not provide a statistically significant improvement to predictions of time to menopause than age alone (Age C-statistic = 84%, 95% CI 83–86%; Age + AMH C-statistic = 86%, 95% CI 85–87%) [232]. These findings indicate that there is utility in introducing normative age-ranges as a supplementary criterion for defining stages of reproductive ageing. Compared with the establishment of standardised biomarker assays, the use of normative age-ranges can be done relatively quickly and reliably, using available evidence from multiple large population studies, such as the UK Biobank study [234]. This need is recognised by the number of studies in this review with a definition that has attempted to use age to further clarify menopausal status (Premenopause: 19.48%; Postmenopause: 11.76%). Moreover, the use of age as an additional component of the supportive criteria for determining reproductive stage becomes further evident when women who use HRT or suffer from chronic illness are considered. For example, a systematic review with meta-analysis of randomised controlled trials showed that the incidence of chemotherapy induced amenorrhea is 61% (95% CI 51–68%) for women with breast cancer [235]. For these women, the current use of principal criteria, which relies solely on menstrual cycles, is inadequate. This emphasises the urgent need to expand the supportive criteria to ensure STRAW + 10 can be utilised by women using HRT or suffering from chronic illness that impacts menstrual cycles.

Altogether, 33.77% of studies that defined premenopause and 11.76% of studies that defined postmenopause used criteria inconsistent with STRAW criteria. The disproportionate use of additional criteria for defining premenopause compared with postmenopause is further indication that the term premenopause is not precisely and systematically defined by the STRAW criteria. This has prompted researchers to use additional/alternative criteria to achieve clarity. Unfortunately, the consequence of non-standardised criteria is increased heterogeneity, which can lead to the synthesis of imprecise estimates. Moreover, of the 128 included studies, 39.84% did not report definitions/criteria for premenopausal women, whereas, only 20.31% did not report definitions/criteria for postmenopausal women. This difference may reflect a belief that the definition/criteria for premenopausal women is widely understood, with no need for further clarification by authors. However, in the context of the findings presented in this review, it is more likely these trends reflect a poor understanding of the term premenopause compared with postmenopause.

Conclusion

There is a significant amount of heterogeneity associated with the definition of premenopause, compared with postmenopause. We propose three key suggestions/recommendations, which can be distilled from these findings. Firstly, premenopause, which is not currently explicitly stated in STRAW or STRAW + 10, should be transparently operationalised and reported. Secondly, as a minimum requirement, regular menstruation should be defined as the number of menstrual cycles in a period of at least 3 months. Finally, the utility of introducing normative age-ranges as supplementary criterion for defining stages of reproductive ageing should be considered. The use of consistent terminology in research will enhance our capacity to compare results from different studies and more effectively investigate issues related to women’s health and ageing.

References

Ambikairajah A, Walsh E, Tabatabaei-Jafari H, Cherbuin N. Fat mass changes during menopause: a metaanalysis. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2019;221:393-409.e50.

Ambikairajah A, Walsh E, Cherbuin N. Lipid profile differences during menopause: a review with meta-analysis. Menopause. 2019. https://doi.org/10.1097/GME.0000000000001403.

Ambikairajah A, Tabatabaei-Jafari H, Walsh E, Hornberger M, Cherbuin N. Longitudinal changes in fat mass and the hippocampus. Obesity. 2020;28:1263–9.

Ambikairajah A, Tabatabaei-Jafari H, Hornberger M, Cherbuin N. Age, menstruation history, and the brain. Menopause. 2021;28:167–74.

GBD 2019 Collaborators. Global mortality from dementia: application of a new method and results from the Global Burden of Disease Study 2019. Alzheimer’s Dement. 2021;7:e12200.

Mikkola TS, Gissler M, Merikukka M, Tuomikoski P, Ylikorkala O. Sex differences in age-related cardiovascular mortality. PLoS ONE. 2013;8:e63347.

McAloon CJ, Boylan LM, Hamborg T. The changing face of cardiovascular disease 2000: an analysis of the world health organisation global health estimates data. Int J Cardiol. 2016;224:256–64.

Taylor CM, Pritschet L, Yu S, Jacobs EG. Applying a women’s health lens to the study of the aging brain. Front Hum Neurosci. 2019. https://doi.org/10.3389/fnhum.2019.00224.

World Health Organization. Research on the menopause in the 1990s: report of a WHO scientific group. Geneva: World Health Organization; 1996.

World Health Organization. Research on the menopause: report of a WHO scientific group [meeting held in Geneva from 8 to 12]. Geneva: World Health Organization; 1980.

Harlow SD, Gass M, Hall JE, Lobo R, Maki P, Rebar RW, et al. Executive summary of the stages of reproductive aging workshop + 10: addressing the unfinished agenda of staging reproductive aging. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2012;97:1159–68.

Harlow SD, Crawford S, Dennerstein L, Burger HG, Mitchell ES, Sowers M-F, et al. Recommendations from a multi-study evaluation of proposed criteria for staging reproductive aging. Climacteric. 2007;10:112–9.

Utian WH. The international menopause menopause-related terminology definitions. Climacteric. 1999;2:284–6.

Soules MR, Sherman S, Parrott E, Rebar R, Santoro N, Utian W, et al. Executive summary: stages of reproductive aging workshop (STRAW). Climacteric. 2001;4:267–72.

Harlow SD, Cain K, Crawford S, Dennerstein L, Little R, Mitchell ES, et al. Evaluation of four proposed bleeding criteria for the onset of late menopausal transition. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2006;91:3432–8.

Harlow SD, Mitchell ES, Crawford S, Nan B, Little R, Taffe J. The ReSTAGE Collaboration: defining optimal bleeding criteria for onset of early menopausal transition. Fertil Steril. 2008;89:129–40.

Abate M, Schiavone C, Di Carlo L, Salini V. Prevalence of and risk factors for asymptomatic rotator cuff tears in postmenopausal women. Menopause. 2014;21:275–80.

Abdulnour J, Doucet E, Brochu M. The effect of the menopausal transition on body composition and cardiometabolic risk factors: a Montreal–Ottawa New Emerging Team group study. Menopause. 2012. https://doi.org/10.1097/gme.0b013e318240f6f3.

Abildgaard J, Pedersen AT, Green CJ. Menopause is associated with decreased whole body fat oxidation during exercise. Am J Physiol Endocrinol Metab. 2013;304:E1227–36.

Adams-Campbell LL, Kim KS, Dunston G, Laing AE, Bonney G, Demenais F. The relationship of body mass index to reproductive factors in pre- and postmenopausal African-American women with and without breast cancer. Obes Res. 1996;4:451–6.

Agrinier N, Cournot M, Dallongeville J. Menopause and modifiable coronary heart disease risk factors: a population based study. Maturitas. 2010;65:237–43.

Aguado F, Revilla M, Hernandez ER, Villa LF, Rico H. Behavior of bone mass measurements. Dual energy x-ray absorptiometry total body bone mineral content, ultrasound bone velocity, and computed metacarpal radiogrammetry, with age, gonadal status, and weight in healthy women. Invest Radiol. 1996;31:218–22.

Albanese CV, Cepollaro C, Terlizzi F, Brandi ML, Passariello R. Performance of five phalangeal QUS parameters in the evaluation of gonadal-status, age and vertebral fracture risk compared with DXA. Ultrasound Med Biol. 2009;35:537–44.

Allali F, El Mansouri L, Abourazzak F. The effect of past use of oral contraceptive on bone mineral density, bone biochemical markers and muscle strength in healthy pre and post menopausal women. BMC Women’s Health. 2009. https://doi.org/10.1186/1472-6874-9-31.

Aloia JF, Vaswani A, Ma R, Flaster E. To what extent is bone mass determined by fat-free or fat mass? Am J Clin Nutr. 1995;61:1110–4.

Amankwah EK, Friedenreich CM, Magliocco AM. Anthropometric measures and the risk of endometrial cancer, overall and by tumor microsatellite status and histological subtype. Am J Epidemiol. 2013;177:1378–87.

Amarante F, Vilodre LC, Maturana MA, Spritzer PM. Women with primary ovarian insufficiency have lower bone mineral density. Braz J Med Biol Res. 2011;44:78–83.

Amiri P, Deihim T, Nakhoda K, Hasheminia M, Montazeri A, Azizi F. Metabolic syndrome and health-related quality of life in reproductive age and post-menopausal women: Tehran Lipid and Glucose Study. Arch Iran Med. 2014;17:423–8.

Angsuwathana S, Leerasiri P, Rattanachaiyanont M. Health check-up program for pre/postmenopausal women at Siriraj Menopause Clinic. J Med Assoc Thai. 2007;90:1–8.

Armellini F, Zamboni M, Perdichizzi G. Computed tomography visceral adipose tissue volume measurements of Italians. Predictive equations. Eur J Clin Nutr. 1996;50:290–4.

Arthur FK, Adu-Frimpong M, Osei-Yeboah J, Mensah FO, Owusu L. The prevalence of metabolic syndrome and its predominant components among pre-and postmenopausal Ghanaian women. BMC Res Notes. 2013. https://doi.org/10.1186/1756-0500-6-446.

Aydin ZD. Determinants of age at natural menopause in the Isparta Menopause and Health Study: premenopausal body mass index gain rate and episodic weight loss. Menopause. 2010. https://doi.org/10.1097/gme.0b013e3181c73093.

Ayub N, Khan SR, Syed F. Leptin levels in pre and post menopausal Pakistani women. JPMA. 2006;56:3–5.

Bancroft J, Cawood EH. Androgens and the menopause; a study of 40–60-year-old women. Clin Endocrinol. 1996;45:577–87.

Bednarek-Tupikowska G, Filus A, Kuliczkowska-Plaksej J, Tupikowski K, Bohdanowicz-Pawlak A, Milewicz A. Serum leptin concentrations in pre- and postmenopausal women on sex hormone therapy. Gynecol Endocrinol. 2006;22:207–12.

Bell RJ, Davison SL, Papalia M-A, McKenzie DP, Davis SR. Endogenous androgen levels and cardiovascular risk profile in women across the adult life span. Menopause. 2007;14:630–8.

Ben Ali S, Jemaa R, Ftouhi B, Kallel A, Feki M, Slimene H, et al. Relationship of plasma leptin and adiponectin concentrations with menopausal status in Tunisian women. Cytokine. 2011;56:338–42.

Ben Ali S, Belfki-Benali H, Aounallah-Skhiri H, Traissac P, Maire B, Delpeuch F, et al. Menopause and metabolic syndrome in Tunisian women. BioMed Res Int. 2014;2014:e457131.

Ben Ali S, Belfki-Benali H, Ahmed DB, Haddad N, Jmal A, Abdennebi M, et al. Postmenopausal hypertension, abdominal obesity, apolipoprotein and insulin resistance. Clin Exp Hypertens. 2016;38:370–4.

Berg G, Mesch V, Boero L. Lipid and lipoprotein profile in menopausal transition. Effects of hormones, age and fat distribution. Horm Metab Res. 2004;36:215–20.

Berge LN, Bonaa KH, Nordoy A. Serum ferritin, sex hormones, and cardiovascular risk factors in healthy women. Arterioscler Thromb. 1994;14:857–61.

Berger GM, Naidoo J, Gounden N, Gouws E. Marked hyperinsulinaemia in postmenopausal, healthy Indian (Asian) women. Diabet Med. 1995;12:788–95.

Berstad P, Coates RJ, Bernstein L. A case-control study of body mass index and breast cancer risk in white and African-American women. Cancer Epidemiol Biomark Prev. 2010;19:1532–44.

Bhagat M, Mukherjee S, De P. Clustering of cardiometabolic risk factors in Asian Indian women: Santiniketan women study. Menopause. 2010. https://doi.org/10.1097/gme.0b013e3181bfac28.

Bhurosy T, Jeewon R. Food habits, socioeconomic status and body mass index among premenopausal and post-menopausal women in Mauritius. J Hum Nutr Diet. 2013;1:114–22.

Blumenthal JA, Fredrikson M, Matthews KA. Stress reactivity and exercise training in premenopausal and postmenopausal women. Health Psychol. 1991;10:384–91.

Bonithon-Kopp C, Scarabin PY, Darne B, Malmejac A, Guize L. Menopause-related changes in lipoproteins and some other cardiovascular risk factors. Int J Epidemiol. 1990;19:42–8.

Caire-Juvera G, Arendell LA, Maskarinec G, Thomson CA, Chen Z. Associations between mammographic density and body composition in Hispanic and non-Hispanic white women by menopause status. Menopause. 2008. https://doi.org/10.1097/gme.0b013e3181405b8a.

Campesi I, Occhioni S, Tonolo G. Ageing/menopausal status in healthy women and ageing in healthy men differently affect cardiometabolic parameters. Int J Med Sci. 2016;13:124–32.

Carr MC, Kim KH, Zambon A. Changes in LDL density across the menopausal transition. J Invest Med. 2000;48:245–50.

Castracane VD, Kraemer RR, Franken MA, Kraemer GR, Gimpel T. Serum leptin concentration in women: effect of age, obesity, and estrogen administration. Fertil Steril. 1998;70:472–7.

Catsburg C, Kirsh VA, Soskolne CL. Associations between anthropometric characteristics, physical activity, and breast cancer risk in a Canadian cohort. Breast Cancer Res Treat. 2014;145:545–52.

Cecchini RS, Costantino JP, Cauley JA. Body mass index and the risk for developing invasive breast cancer among high-risk women in NSABP P-1 and STAR breast cancer prevention trials. Cancer Prev Res (Philadelphia, Pa). 2012;5:583–92.

Cervellati C, Pansini FS, Bonaccorsi G. Body mass index is a major determinant of abdominal fat accumulation in pre-, peri- and post-menopausal women. Gynecol Endocrinol. 2009;25:413–7.

Chain A, Crivelli M, Faerstein E, Bezerra FF. Association between fat mass and bone mineral density among Brazilian women differs by menopausal status: the Pro-Saude Study. Nutrition. 2017;33:14–9.

Chang CJ, Wu CH, Yao WJ, Yang YC, Wu JS, Lu FH. Relationships of age, menopause and central obesity on cardiovascular disease risk factors in Chinese women. Int J Obes Relat Metab Disord. 2000;24:1699–704.

Cho GJ, Lee JH, Park HT. Postmenopausal status according to years since menopause as an independent risk factor for the metabolic syndrome. Menopause. 2008. https://doi.org/10.1097/gme.0b013e3181559860.

Cifkova R, Pitha J, Lejskova M, Lanska V, Zecova S. Blood pressure around the menopause: a population study. J Hypertens. 2008;26:1976–82.

Copeland AL, Martin PD, Geiselman PJ, Rash CJ, Kendzor DE. Predictors of pretreatment attrition from smoking cessation among pre- and postmenopausal, weight-concerned women. Eat Behav. 2006;7:243–51.

Cremonini E, Bonaccorsi G, Bergamini CM. Metabolic transitions at menopause: in post-menopausal women the increase in serum uric acid correlates with abdominal adiposity as assessed by DXA. Maturitas. 2013;75:62–6.

Cui LH, Shin MH, Kweon SS. Relative contribution of body composition to bone mineral density at different sites in men and women of South Korea. J Bone Miner Metab. 2007;25:165–71.

da Câmara SM, Zunzunegui MV, Pirkle C, Moreira MA, Maciel ÁC. Menopausal status and physical performance in middle aged women: a cross-sectional community-based study in Northeast Brazil. PLoS ONE. 2015;10:e0119480.

Dallongeville J, Marecaux N, Isorez D, Zylbergberg G, Fruchart JC, Amouyel P. Multiple coronary heart disease risk factors are associated with menopause and influenced by substitutive hormonal therapy in a cohort of French women. Atherosclerosis. 1995;118:123–33.

Dancey DR, Hanly PJ, Soong C, Lee B, Hoffstein V. Impact of menopause on the prevalence and severity of sleep apnea. Chest. 2001;120:151–5.

Davis CE, Pajak A, Rywik S. Natural menopause and cardiovascular disease risk factors. The Poland and US Collaborative Study on Cardiovascular Disease Epidemiology. Ann Epidemiol. 1994;4:445–8.

De Kat AC, Dam V, Onland-Moret NC, Eijkemans MJC, Broekmans FJM, Van Der Schouw YT. Unraveling the associations of age and menopause with cardiovascular risk factors in a large population-based study. BMC Med. 2017;15:2.

den Tonkelaar I, Seidell JC, van Noord PA, Baanders-van Halewijn EA, Ouwehand IJ. Fat distribution in relation to age, degree of obesity, smoking habits, parity and estrogen use: a cross-sectional study in 11,825 Dutch women participating in the DOM-project. Int J Obes. 1990;14:753–61.

D’Haeseleer E, Depypere H, Claeys S, Van Lierde KM. The relation between body mass index and speaking fundamental frequency in premenopausal and postmenopausal women. Menopause. 2011. https://doi.org/10.1097/gme.0b013e31820612d5.

Dmitruk A, Czeczelewski J, Czeczelewska E, Golach J, Parnicka U. Body composition and fatty tissue distribution in women with various menstrual status. Roczniki Panstwowego Zakladu Higieny. 2018;69:95–101.

Donato GB, Fuchs SC, Oppermann K, Bastos C, Spritzer PM. Association between menopause status and central adiposity measured at different cutoffs of waist circumference and waist-to-hip ratio. Menopause. 2006. https://doi.org/10.1097/01.gme.0000177907.32634.ae.

Douchi T, Oki T, Nakamura S, Ijuin H, Yamamoto S, Nagata Y. The effect of body composition on bone density in pre- and postmenopausal women. Maturitas. 1997;27:55–60.

Douchi T, Yamamoto S, Yoshimitsu N, Andoh T, Matsuo T, Nagata Y. Relative contribution of aging and menopause to changes in lean and fat mass in segmental regions. Maturitas. 2002;42:301–6.

Douchi T, Yonehara Y, Kawamura Y, Kuwahata A, Kuwahata T, Iwamoto I. Difference in segmental lean and fat mass components between pre-and postmenopausal women. Menopause. 2007;14:875–8.

Dubois EF, Bergh JP, Smals AG, Meerendonk CW, Zwinderman AH, Schweitzer DH. Comparison of quantitative ultrasound parameters with dual energy X-ray absorptiometry in pre- and postmenopausal women. Neth J Med. 2001;58:62–70.

Engmann NJ, Golmakani MK, Miglioretti DL, Sprague BL, Kerlikowske K. Population-attributable risk proportion of clinical risk factors for breast cancer. JAMA Oncol. 2017;3:1228–36.

Ertungealp E, Seyisoglu H, Erel CT, Senturk LM, Gezer A. Changes in bone mineral density with age, menopausal status and body mass index in Turkish women. Climacteric. 1999;2:45–51.

Feng Y, Hong X, Wilker E. Effects of age at menarche, reproductive years, and menopause on metabolic risk factors for cardiovascular diseases. Atherosclerosis. 2008;196:590–7.

Formica C, Loro ML, Gilsanz V, Seeman E. Inhomogeneity in body fat distribution may result in inaccuracy in the measurement of vertebral bone mass. J Bone Miner Res. 1995;10:1504–11.

Friedenreich CM, Courneya KS, Bryant HE. Case–control study of anthropometric measures and breast cancer risk. Int J Cancer. 2002;99:445–52.

Friedenreich C, Cust A, Lahmann PH. Anthropometric factors and risk of endometrial cancer: the European prospective investigation into cancer and nutrition. Cancer Causes Control. 2007;18:399–413.

Fu X, Ma X, Lu H, He W, Wang Z, Zhu S. Associations of fat mass and fat distribution with bone mineral density in pre- and postmenopausal Chinese women. Osteoporosis Int. 2011;22:113–9.

Fuh J-L, Wang S-J, Lee S-J, Lu S-R, Juang K-D. Quality of life and menopausal transition for middle-aged women on Kinmen island. Qual Life Res. 2003;12:53–61.

Gambacciani M, Ciaponi M, Cappagli B, Benussi C, De Simone L, Genazzani AR. Climacteric modifications in body weight and fat tissue distribution. Climacteric. 1999;2:37–44.

Genazzani AR, Gambacciani M. Effect of climacteric transition and hormone replacement therapy on body weight and body fat distribution. Gynecol Endocrinol. 2006;22:145–50.

Ghosh A. Comparison of risk variables associated with the metabolic syndrome in pre- and postmenopausal Bengalee women. Cardiovasc J Afr. 2008;19:183–7.

Ghosh A, Bhagat M. Anthropometric and body composition characteristics in pre- and postmenopausal Asian Indian women: Santiniketan women study. Anthropologischer Anzeiger. 2010;68:1–10.

Gram IT, Funkhouser E, Tabar L. Anthropometric indices in relation to mammographic patterns among peri-menopausal women. Int J Cancer. 1997;73:323–6.

Guerrero RTL, Novotny R, Wilkens LR, Chong M, White KK, Shvetsov YB, et al. Risk factors for breast cancer in the breast cancer risk model study of Guam and Saipan. Cancer Epidemiol. 2017;50:221–33.

Guo W, Bradbury KE, Reeves GK, Key TJ. Physical activity in relation to body size and composition in women in UK Biobank. Ann Epidemiol. 2015;25:406-413.e6.

Gurka MJ, Vishnu A, Santen RJ, DeBoer MD. Progression of metabolic syndrome severity during the menopausal transition. J Am Heart Assoc. 2016. https://doi.org/10.1161/JAHA.116.003609.

Hadji P, Hars O, Bock K. The influence of menopause and body mass index on serum leptin concentrations. Eur J Endocrinol. 2000;143:55–60.

Hagner W, Hagner-Derengowska M, Wiacek M, Zubrzycki IZ. Changes in level of V O2max, blood lipids, and waist circumference in the response to moderate endurance training as a function of ovarian aging. Menopause. 2009;16:1009–13.

Han D, Nie J, Bonner MR. Lifetime adult weight gain, central adiposity, and the risk of pre- and postmenopausal breast cancer in the Western New York exposures and breast cancer study. Int J Cancer. 2006;119:2931–7.

Harting GH, Moore CE, Mitchell R, Kappus CM. Relationship of menopausal status and exercise level to HDL-cholesterol in women. Exp Aging Res. 1984;10:13–8.

He L, Tang X, Li N. Menopause with cardiovascular disease and its risk factors among rural Chinese women in Beijing: a population-based study. Maturitas. 2012;72:132–8.

Hirose K, Tajima K, Hamajima N, Takezaki T, Inoue M, Kuroishi T, et al. Impact of established risk factors for breast cancer in nulligravid Japanese women. Breast Cancer. 2003;10:45.

Hjartaker A, Adami HO, Lund E, Weiderpass E. Body mass index and mortality in a prospectively studied cohort of Scandinavian women: the women’s lifestyle and health cohort study. Eur J Epidemiol. 2005;20:747–54.

Ho S, Wu S, Chan S, Sham A. Menopausal transition and changes of body composition: a prospective study in Chinese perimenopausal women. Int J Obes. 2010;34(8):1265–74.

Hsu Y-H, Venners SA, Terwedow HA, Feng Y, Niu T, Li Z, et al. Relation of body composition, fat mass, and serum lipids to osteoporotic fractures and bone mineral density in Chinese men and women. Am J Clin Nutr. 2006;83:146–54.

Hu X, Pan X, Ma X. Contribution of a first-degree family history of diabetes to increased serum adipocyte fatty acid binding protein levels independent of body fat content and distribution. Int J Obes. 2005;40:1649–54.

Hunter G, Kekes-Szabo T, Treuth M, Williams M, Goran M, Pichon C. Intra-abdominal adipose tissue, physical activity and cardiovascular risk in pre- and post-menopausal women. Int J Obes Relat Metab Disord. 1996;20:860–5.

Iida T, Domoto T, Takigawa A. Relationships among blood leptin and adiponectin levels, fat mass, and bone mineral density in Japanese pre- and postmenopausal women. Hiroshima J Med Sci. 2011;60:71–8.

Ilich-Ernst J, Brownbill RA, Ludemann MA, Fu R. Critical factors for bone health in women across the age span: how important is muscle mass? Medscape Women’s Health. 2002;7(3):2.

Ito M, Hayashi K, Uetani M, Yamada M, Ohki M, Nakamura T. Association between anthropometric measures and spinal bone mineral density. Invest Radiol. 1994;29:812–6.

Jaff NG, Norris SA, Snyman T, Toman M, Crowther NJ. Body composition in the Study of Women Entering and in Endocrine Transition (SWEET): a perspective of African women who have a high prevalence of obesity and HIV infection. Metabolism. 2015;64:1031–41.

Jasienska G, Ziomkiewicz A, Gorkiewicz M, Pajak A. Body mass, depressive symptoms and menopausal status: an examination of the “Jolly Fat” hypothesis. Women’s Health Issues. 2005;15:145–51.

Jeenduang N, Trongsakul R, Inhongsa P, Chaidach P. The prevalence of metabolic syndrome in premenopausal and postmenopausal women in Southern Thailand. Gynecol Endocrinol. 2014;30:573–6.

Jeon YK, Lee JG, Kim SS. Association between bone mineral density and metabolic syndrome in pre- and postmenopausal women. Endocr J. 2011;58:87–93.

Jurimae J, Jurimae T. Plasma adiponectin concentration in healthy pre- and postmenopausal women: relationship with body composition, bone mineral, and metabolic variables. Am J Physiol Endocrinol Metab. 2007;293:E42–7.

Kadam N, Chiplonkar S, Khadilkar A, Divate U, Khadilkar V. Low bone mass in urban Indian women above 40 years of age: prevalence and risk factors. Gynecol Endocrinol. 2010;26:909–17.

Kang EK, Park HW, Baek S, Lim JY. The association between trunk body composition and spinal bone mineral density in Korean males versus females: a farmers’ cohort for agricultural work-related musculoskeletal disorders (FARM) study. J Korean Med Sci. 2016;31:1595–603.

Kaufer-Horwitz M, Pelaez-Robles K, Lazzeri-Arteaga P, Goti-Rodriguez LM, Avila-Rosas H. Hypertension, overweight and abdominal adiposity in women. An analytical perspective. Arch Med Res. 2005;36:404–11.

Kim HM, Park J, Ryu SY, Kim J. The effect of menopause on the metabolic syndrome among Korean women: the Korean National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey, 2001. Diabetes Care. 2007;30:701–6.

Kim JH, Choi HJ, Kim MJ, Shin CS, Cho NH. Fat mass is negatively associated with bone mineral content in Koreans. Osteoporos Int. 2012;23:2009–16.

Kim S, Lee JY, Im JA. Association between serum osteocalcin and insulin resistance in postmenopausal, but not premenopausal, women in Korea. Menopause. 2013;20:1061–6.

Kim YM, Kim SH, Kim S, Yoo JS, Choe EY, Won YJ. Variations in fat mass contribution to bone mineral density by gender, age, and body mass index: the Korea National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey (KNHANES) 2008. Osteoporos Int. 2016;27:2543–54.

Kirchengast S, Hartmann B, Huber J. Serum levels of sex hormones, thyroid hormones, growth hormone, IGF I, and cortisol and their relations to body fat distribution in healthy women dependent on their menopausal status. Z Morphol Anthropol. 1996;81:223–34.

Kirchengast S, Gruber D, Sator M, Huber J. Impact of the age at menarche on adult body composition in healthy pre- and postmenopausal women. Am J Phys Anthropol. 1998;105:9–20.

Knapp KM, Blake GM, Spector TD, Fogelman I. Multisite quantitative ultrasound: precision, age-and menopause-related changes, fracture discrimination, and T-score equivalence with dual-energy X-ray absorptiometry. Osteoporos Int. 2001;12:456–64.

Koh SJ, Hyun YJ, Choi SY. Influence of age and visceral fat area on plasma adiponectin concentrations in women with normal glucose tolerance. Clin Chim Acta. 2008;389:45–50.

Konrad T, Bär F, Schneider F. Factors influencing endothelial function in healthy pre- and post-menopausal women of the EU-RISC study. Diab Vasc Dis Res. 2011;8:229–36.

Kontogianni MD, Dafni UG, Routsias JG, Skopouli FN. Blood leptin and adiponectin as possible mediators of the relation between fat mass and BMD in perimenopausal women. J Bone Miner Res. 2004;19:546–51.

Konukoglu D, Serin O, Ercan M. Plasma leptin levels in obese and non-obese postmenopausal women before and after hormone replacement therapy. Maturitas. 2000;36:203–7.

Koskova I, Petrasek R, Vondra K. Weight, body composition and fat distribution of Czech women in relation with reproductive phase: a cross-sectional study. Prague Med Rep. 2007;108:13–26.

Kotani K, Chen JT, Taniguchi N. The relationship between adiponectin and blood pressure in premenopausal and postmenopausal women. Clin Invest Med. 2011;34:E125–30.

Kraemer RR, Synovitz LB, Gimpel T, Kraemer GR, Johnson LG, Castracane VD. Effect of estrogen on serum DHEA in younger and older women and the relationship of DHEA to adiposity and gender. Metabolism. 2001;50:488–93.

Kuk JL, Lee S, Heymsfield SB, Ross R. Waist circumference and abdominal adipose tissue distribution: influence of age and sex. Am J Clin Nutr. 2005;81:1330–4.

Laitinen K, Valimaki M, Keto P. Bone mineral density measured by dual-energy X-ray absorptiometry in healthy Finnish women. Calcif Tissue Int. 1991;48:224–31.

Lejskova M, Alusik S, Valenta Z, Adamkova S, Pitha J. Natural postmenopause is associated with an increase in combined cardiovascular risk factors. Physiol Res. 2012;61:587–96.

Ley CJ, Lees B, Stevenson JC. Sex- and menopause-associated changes in body-fat distribution. Am J Clin Nutr. 1992;55:950–4.

Lin WY, Yang WS, Lee LT. Insulin resistance, obesity, and metabolic syndrome among non-diabetic pre- and post-menopausal women in North Taiwan. Int J Obes. 2005;30:912–7.

Lindquist O, Bengtsson C. Serum lipids, arterial blood pressure and body weight in relation to the menopause: results from a population study of women in Goteborg, Sweden. Scand J Clin Lab Invest. 1980;40:629–36.

Lindsay R, Cosman F, Herrington BS, Himmelstein S. Bone mass and body composition in normal women. J Bone Miner Res. 1992;7:55–63.

Lovejoy JC, Champagne CM, Jonge L, Xie H, Smith S. Increased visceral fat and decreased energy expenditure during the menopausal transition. Int J Obes. 2005;32:949–58.

Lyu LC, Yeh CY, Lichtenstein AH, Li Z, Ordovas JM, Schaefer EJ. Association of sex, adiposity, and diet with HDL subclasses in middle-aged Chinese. Am J Clin Nutr. 2001;74:64–71.

Maharlouei N, Bellissimo N, Ahmadi SM, Lankarani KB. Prevalence of metabolic syndrome in pre- and postmenopausal Iranian women. Climacteric. 2013;16:561–7.

Malacara JM, Cetina T, Bassol S. Symptoms at pre- and postmenopause in rural and urban women from three States of Mexico. Maturitas. 2002;43:11–9.

Manabe E, Aoyagi K, Tachibana H, Takemoto T. Relationship of intra-abdominal adiposity and peripheral fat distribution to lipid metabolism in an island population in western Japan: gender differences and effect of menopause. Tohoku J Exp Med. 1999;188:189–202.

Manjer J, Kaaks R, Riboli E, Berglund G. Risk of breast cancer in relation to anthropometry, blood pressure, blood lipids and glucose metabolism: a prospective study within the Malmo Preventive Project. Eur J Cancer Prev. 2001;10:33–42.

Mannisto S, Pietinen P, Pyy M, Palmgren J, Eskelinen M, Uusitupa M. Body-size indicators and risk of breast cancer according to menopause and estrogen-receptor status. Int J Cancer. 1996;68:8–13.

Martini G, Valenti R, Giovani S, Nuti R. Age-related changes in body composition of healthy and osteoporotic women. Maturitas. 1997;27:25–33.

Marwaha RK, Garg MK, Tandon N, Mehan N, Sastry A, Bhadra K. Relationship of body fat and its distribution with bone mineral density in Indian population. J Clin Densitom. 2013;16:353–9.

Matsushita H, Kurabayashi T, Tomita M, Kato N, Tanaka K. Effects of uncoupling protein 1 and Beta3-adrenergic receptor gene polymorphisms on body size and serum lipid concentrations in Japanese women. Maturitas. 2003;45:39–45.

Matsuzaki M, Kulkarni B, Kuper H. Association of hip bone mineral density and body composition in a rural Indian population: the Andhra Pradesh children and parents study (APCAPS). PLoS ONE. 2017;12:e0167114.

Matthews KA, Meilahn E, Kuller LH, Kelsey SF, Caggiula AW, Wing RR. Menopause and risk factors for coronary heart disease. N Engl J Med. 1989;321:641–6.

Mesch VR, Boero LE, Siseles NO. Metabolic syndrome throughout the menopausal transition: influence of age and menopausal status. Climacteric. 2006;9:40–8.

Meza-Munoz DE, Fajardo ME, Perez-Luque EL, Malacara JM. Factors associated with estrogen receptors-alpha (ER-alpha) and -beta (ER-beta) and progesterone receptor abundance in obese and non obese pre- and post-menopausal women. Steroids. 2006;71:498–503.

Minatoya M, Kutomi G, Shima H. Relation of serum adiponectin levels and obesity with breast cancer: a Japanese case–control study. Asian Pac J Cancer Prev. 2014;15:8325–30.

Mo D, Hsieh P, Yu H. The relationship between osteoporosis and body composition in pre- and postmenopausal women from different ethnic groups in China. Ethn Health. 2017;22:295–310.

Muchanga Sifa MJ, Lepira FB, Longo AL, Sumaili EK, Makulo JR, Mbelambela EP, et al. Prevalence and predictors of metabolic syndrome among Congolese pre- and postmenopausal women. Climacteric. 2014;17:442–8.

Muti P, Stanulla M, Micheli A. Markers of insulin resistance and sex steroid hormone activity in relation to breast cancer risk: a prospective analysis of abdominal adiposity, sebum production, and hirsutism (Italy). Cancer Causes Control. 2000;11:721–30.

Nitta J, Nojima M, Ohnishi H. Weight gain and alcohol drinking associations with breast cancer risk in Japanese postmenopausal women—results from the Japan Collaborative Cohort (JACC) Study. Asian Pac J Cancer Prev. 2016;17:1437–43.

Noh HM, Song YM, Park JH, Kim BK, Choi YH. Metabolic factors and breast cancer risk in Korean women. Cancer Causes Control. 2013;24:1061–8.

Nordin BE, Need AG, Bridges A, Horowitz M. Relative contributions of years since menopause, age, and weight to vertebral density in postmenopausal women. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 1992;74:20–3.

Ohta H, Kuroda T, Onoe Y. Familial correlation of bone mineral density, birth data and lifestyle factors among adolescent daughters, mothers and grandmothers. J Bone Miner Metab. 2010;28:690–5.

Oldroyd B, Stewart SP, Truscott JG, Westmacott CF, Smith MA. Age related changes in body composition. Appl Radiat Isot. 1998;49:589.

Pacholczak R, Klimek-Piotrowska W, Kuszmiersz P. Associations of anthropometric measures on breast cancer risk in pre- and postmenopausal womena case–control study. J Physiol Anthropol. 2016. https://doi.org/10.1186/s40101-016-0090-x.

Park J-H, Song Y-M, Sung J, Lee K, Kim YS, Kim T, et al. The association between fat and lean mass and bone mineral density: the Healthy Twin Study. Bone. 2012;50:1006–11.

Park YM, White AJ, Nichols HB, O’Brien KM, Weinberg CR, Sandler DP. The association between metabolic health, obesity phenotype and the risk of breast cancer. Int J Cancer. 2017;140:2657–66.

Pavlica T, Mikalacki M, Matic R. Relationship between BMI and skinfold thicknesses to risk factors in premenopausal and postmenopausal women. Coll Antropol. 2013;2:119–24.

Phillips GB, Jing T, Heymsfield SB. Does insulin resistance, visceral adiposity, or a sex hormone alteration underlie the metabolic syndrome? Studies in women. Metabolism. 2008;57:838–44.

Polesel DN, Hirotsu C, Nozoe KT, Boin AC, Bittencourt L, Tufik S, et al. Waist circumference and postmenopause stages as the main associated factors for sleep apnea in women: a cross-sectional population-based study. Menopause. 2015;22:835–44.

Pollan M, Lope V, Miranda-Garcia J. Adult weight gain, fat distribution and mammographic density in Spanish pre- and post-menopausal women (DDM-Spain). Breast Cancer Res Treat. 2012;134:823–38.

Portaluppi F, Pansini F, Manfredini R, Mollica G. Relative influence of menopausal status, age, and body mass index on blood pressure. Hypertension. 1997;29:976–9.

Priya T, Chowdhury MG, Vasanth K. Assessment of serum leptin and resistin levels in association with the metabolic risk factors of pre- and post-menopausal rural women in South India. Diabetes Metab Syndr. 2013;7:233–7.

Rantalainen T, Nikander R, Heinonen A. Neuromuscular performance and body mass as indices of bone loading in premenopausal and postmenopausal women. Bone. 2010;46:964–9.

Reina P, Cointry GR, Nocciolino L. Analysis of the independent power of age-related, anthropometric and mechanical factors as determinants of the structure of radius and tibia in normal adults. A pQCT study. J Musculoskelet Neuronal Interact. 2015;15:10–22.

Revilla M, Villa LF, Hernandez ER, Sanchez-Atrio A, Cortes J, Rico H. Influence of weight and gonadal status on total and regional bone mineral content and on weight-bearing and non-weight-bearing bones, measured by dual-energy X-ray absosorptiometry. Maturitas. 1997;28:69–74.

Rice MS, Bertrand KA, Lajous M. Reproductive and lifestyle risk factors and mammographic density in Mexican women. Ann Epidemiol. 2015;25:868–73.

Rico H, Aguado F, Arribas I, Hernandez ER, Villa LF, Seco C, et al. Behavior of phalangeal bone ultrasound in normal women with relation to gonadal status and body mass index. Osteoporos Int. 2001;12:450–5.

Rico H, Arribas I, Casanova FJ, Duce AM, Herna ER, Cortes-Prieto J. Bone mass, bone metabolism, gonadal status and body mass index. Osteoporos Int. 2002;13:379–87.

Roelfsema F, Veldhuis JD. Growth hormone dynamics in healthy adults are related to age and sex and strongly dependent on body mass index. Neuroendocrinology. 2016;103:335–44.

Rosenbaum M, Nicolson M, Hirsch J. Effects of gender, body composition, and menopause on plasma concentrations of leptin. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 1996;81:3424–7.

Salomaa V, Rasi V, Pekkanen J. Association of hormone replacement therapy with hemostatic and other cardiovascular risk factors. The FINRISK Hemostasis Study. Arterioscler Thromb Vasc Biol. 1995;15:1549–55.

Sarrafzadegan N, Khosravi-Boroujeni H, Esmaillzadeh A, Sadeghi M, Rafieian-Kopaei M, Asgary S. The association between hypertriglyceridemic waist phenotype, menopause, and cardiovascular risk factors. Arch Iran Med. 2013;16:161–6.

Schaberg-Lorei G, Ballard JE, McKeown BC, Zinkgraf SA. Body composition alterations consequent to an exercise program for pre and postmenopausal women. J Sports Med Phys Fit. 1990;30:426–33.

Schwarz S, Völzke H, Alte D, Schwahn C, Grabe HJ, Hoffmann W, et al. Menopause and determinants of quality of life in women at midlife and beyond: the study of health in Pomerania (SHIP). Menopause. 2007;14:123–34.

Shakir YA, Samsioe G, Nyberg P, Lidfeldt J, Nerbrand C. Cardiovascular risk factors in middle-aged women and the association with use of hormone therapy: results from a population-based study of Swedish women. The Women’s Health in the Lund Area (WHILA) Study. Climacteric. 2004;7:274–83.

Sherk VD, Malone SP, Bemben MG, Knehans AW, Palmer IJ, Bemben DA. Leptin, fat mass, and bone mineral density in healthy pre- and postmenopausal women. J Clin Densitom. 2011;14:321–5.

Shibata H, Matsuzaki T, Hatano S. Relationship of relevant factors of atherosclerosis to menopause in Japanese women. Am J Epidemiol. 1979;109:420–4.

Sieminska L, Wojciechowska C, Foltyn W. The relation of serum adiponectin and leptin levels to metabolic syndrome in women before and after the menopause. Endokrynol Pol. 2006;57:15–22.

Skrzypczak M, Szwed A. Assessment of the body mass index and selected physiological parameters in pre- and post-menopausal women. HOMO. 2005;56:141–52.

Skrzypczak M, Szwed A, Pawlińska-Chmara R, Skrzypulec V. Assessment of the BMI, WHR and W/Ht in pre-and postmenopausal women. Anthropol Rev. 2007;70:3–13.

Soderberg S, Ahren B, Eliasson M, Dinesen B, Olsson T. The association between leptin and proinsulin is lost with central obesity. J Intern Med. 2002;252:140–8.

Son MK, Lim NK, Lim JY. Difference in blood pressure between early and late menopausal transition was significant in healthy Korean women. BMC Women’s Health. 2015. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12905-015-0219-9.

Soriguer F, Morcillo S, Hernando V, Valdés S, de Adana MSR, Olveira G, et al. Type 2 diabetes mellitus and other cardiovascular risk factors are no more common during menopause: longitudinal study. Menopause. 2009;16:817–21.

Staessen J, Bulpitt CJ, Fagard R, Lijnen P, Amery A. The influence of menopause on blood pressure. J Hum Hypertens. 1989;3:427–33.

Suarez-Ortegon MF, Arbelaez A, Mosquera M, Mendez F, Aguilar-de PC. C-reactive protein, waist circumference, and family history of heart attack are independent predictors of body iron stores in apparently healthy premenopausal women. Biol Trace Elem Res. 2012;148:135–8.

Suliga E, Koziel D, Ciesla E, Rebak D, Gluszek S. Factors associated with adiposity, lipid profile disorders and the metabolic syndrome occurrence in premenopausal and postmenopausal women. PLoS ONE. 2016;11:e0154511.

Sumner AE, Falkner B, Kushner H, Considine RV. Relationship of leptin concentration to gender, menopause, age, diabetes, and fat mass in African Americans. Obes Res. 1998;6:128–33.

Tanaka NI, Hanawa S, Murakami H. Accuracy of segmental bioelectrical impedance analysis for predicting body composition in pre- and postmenopausal women. J Clin Densitom. 2015;18:252–9.

Thomas T, Burguera B, Melton LJ III, Atkinson EJ, O’Fallon WM, Riggs BL, et al. Relationship of serum leptin levels with body composition and sex steroid and insulin levels in men and women. Metabolism. 2000;49:1278–84.

Torng PL, Su TC, Sung FC. Effects of menopause and obesity on lipid profiles in middle-aged Taiwanese women: the Chin-Shan Community Cardiovascular Cohort Study. Atherosclerosis. 2000;153:413–21.

Toth MJ, Tchernof A, Sites CK, Poehlman ET. Effect of menopausal status on body composition and abdominal fat distribution. Int J Obes Relat Metab Disord. 2000;24:226–31.

Tremollieres FA, Pouilles JM, Ribot CA. Relative influence of age and menopause on total and regional body composition changes in postmenopausal women. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 1996;175:1594–600.

Trikudanathan S, Pedley A, Massaro JM. Association of female reproductive factors with body composition: the Framingham Heart Study. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2013;98:236–44.

Van Pelt RE, Davy KP, Stevenson ET, Wilson TM, Jones PP, Desouza CA, et al. Smaller differences in total and regional adiposity with age in women who regularly perform endurance exercise. Am J Physiol Endocrinol Metab. 1998;275:E626–34.

Veldhuis JD, Dyer RB, Trushin SA, Bondar OP, Singh RJ, Klee GG. Interleukins 6 and 8 and abdominal fat depots are distinct correlates of lipid moieties in healthy pre- and postmenopausal women. Endocrine. 2016;54:671–80.

Wang W, Zhao LJ, Liu YZ, Recker RR, Deng HW. Genetic and environmental correlations between obesity phenotypes and age at menarche. Int J Obes. 2005;30:1595–600.

Wang WS, Wahlqvist ML, Hsu CC, Chang HY, Chang WC, Chen CC. Age- and gender-specific population attributable risks of metabolic disorders on all-cause and cardiovascular mortality in Taiwan. BMC Public Health. 2012. https://doi.org/10.1186/1471-2458-12-111.

Wang F, Ma X, Hao Y. Serum glycated albumin is inversely influenced by fat mass and visceral adipose tissue in Chinese with normal glucose tolerance. PLoS ONE. 2012;7:e51098.

Wee J, Sng BY, Shen L, Lim CT, Singh G, Das De S. The relationship between body mass index and physical activity levels in relation to bone mineral density in premenopausal and postmenopausal women. Arch Osteoporos. 2013. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11657-013-0162-z.

Williams PT, Krauss RM. Associations of age, adiposity, menopause, and alcohol intake with low-density lipoprotein subclasses. Arterioscler Thromb Vasc Biol. 1997;17:1082–90.

Wing RR, Matthews KA, Kuller LH, Meilahn EN, Plantinga PL. Weight gain at the time of menopause. Arch Intern Med. 1991;151:97–102.

Xu L, Nicholson P, Wang QJ, Wang Q, Alen M, Cheng S. Fat mass accumulation compromises bone adaptation to load in Finnish women: a cross-sectional study spanning three generations. J Bone Miner Res. 2010;25:2341–9.

Yamatani H, Takahashi K, Yoshida T, Takata K, Kurachi H. Association of estrogen with glucocorticoid levels in visceral fat in postmenopausal women. Menopause. 2013. https://doi.org/10.1097/gme.0b013e318271a640.

Yannakoulia M, Melistas L, Solomou E, Yiannakouris N. Association of eating frequency with body fatness in pre- and postmenopausal women. Obesity. 2007;15:100–6.

Yoldemir T, Erenus M. The prevalence of metabolic syndrome in pre- and post-menopausal women attending a tertiary clinic in Turkey. Eur J Obstet Gynecol Reprod Biol. 2012;164:172–5.

Yoo KY, Kim H, Shin HR. Female sex hormones and body mass in adolescent and postmenopausal Korean women. J Korean Med Sci. 1998;13:241–6.

Yoo HJ, Park MS, Yang SJ. The differential relationship between fat mass and bone mineral density by gender and menopausal status. J Bone Miner Metab. 2012;30:47–53.

Yoshimoto N, Nishiyama T, Toyama T. Genetic and environmental predictors, endogenous hormones and growth factors, and risk of estrogen receptor-positive breast cancer in Japanese women. Cancer Sci. 2011;102:2065–72.

Žeželj SP, Cvijanović O, Mičović V, Bobinac D, Crnčević-Orlić Ž, Malatestinić G. Effect of menopause, anthropometry, nutrition and lifestyle on bone status of women in the northern Mediterranean. West Indian Med J. 2010;59:494.

Zhong N, Wu XP, Xu ZR. Relationship of serum leptin with age, body weight, body mass index, and bone mineral density in healthy mainland Chinese women. Clin Chim Acta. 2005;351:161–8.

Zhou J-L, Lin S-Q, Shen Y, Chen Y, Zhang Y, Chen F-L. Serum lipid profile changes during the menopausal transition in Chinese women: a community-based cohort study. Menopause. 2010;17:997–1003.

Zhou Y, Zhou X, Guo X. Prevalence and risk factors of hypertension among pre- and post-menopausal women: a cross-sectional study in a rural area of northeast China. Maturitas. 2015;80:282–7.

Zivkovic TB, Vuksanovic M, Jelic MA. Obesity and metabolic syndrome during the menopause transition in Serbian women. Climacteric. 2011;14:643–8.

Akahoshi M, Soda M, Nakashima E. Effects of age at menopause on serum cholesterol, body mass index, and blood pressure. Atherosclerosis. 2001;156:157–63.

Ford K, Sowers M, Crutchfield M, Wilson A, Jannausch M. A longitudinal study of the predictors of prevalence and severity of symptoms commonly associated with menopause. Menopause. 2005;12:308–17.

Franklin RM, Ploutz-Snyder L, Kanaley JA. Longitudinal changes in abdominal fat distribution with menopause. Metabolism. 2009;58:311–5.

Janssen I, Powell LH, Crawford S, Lasley B, Sutton-Tyrrell K. Menopause and the metabolic syndrome: the study of women’s health across the nation. Arch Intern Med. 2008;168:1568–75.

Lee CG, Carr MC, Murdoch SJ. Adipokines, inflammation, and visceral adiposity across the menopausal transition: a prospective study. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2009;94:1104–10.

Liu-Ambrose T, Kravetsky L, Bailey D, Sherar L, Mundt C, Baxter-Jones A, et al. Change in lean body mass is a major determinant of change in areal bone mineral density of the proximal femur: a 12-year observational study. Calcif Tissue Int. 2006;79:145–51.

Macdonald HM, New SA, Campbell MK, Reid DM. Influence of weight and weight change on bone loss in perimenopausal and early postmenopausal Scottish women. Osteoporos Int. 2005;16:163–71.

Razmjou S, Abdulnour J, Bastard J-P, Fellahi S, Doucet É, Brochu M, et al. Body composition, cardiometabolic risk factors, physical activity, and inflammatory markers in premenopausal women after a 10-year follow-up: a MONET study. Menopause. 2018;25:89–97.

Soreca I, Rosano C, Jennings JR, Sheu LK, Kuller LH, Matthews KA, et al. Gain in adiposity across 15 years is associated with reduced gray matter volume in healthy women. Psychosom Med. 2009;71:485–90.

Wells G, Shea B, O’Connell D, Peterson J, Welch V, Losos M, et al. Newcastle–Ottawa quality assessment scale cohort studies. Ottawa: University of Ottawa; 2014.

Smith-DiJulio K, Mitchell ES, Woods NF. Concordance of retrospective and prospective reporting of menstrual irregularity by women in the menopausal transition. Climacteric. 2005;8:390–7.

Kevenaar ME, Meerasahib MF, Kramer P, van de Lang-Born BMN, de Jong FH, Groome NP, et al. Serum anti-Müllerian hormone levels reflect the size of the primordial follicle pool in mice. Endocrinology. 2006;147:3228–34.

de Vet A, Laven JSE, de Jong FH, Themmen APN, Fauser BCJM. Antimüllerian hormone serum levels: a putative marker for ovarian aging. Fertil Steril. 2002;77:357–62.

Feyereisen E, Lozano DHM, Taieb J, Hesters L, Frydman R, Fanchin R. Anti-Müllerian hormone: clinical insights into a promising biomarker of ovarian follicular status. Reprod Biomed Online. 2006;12:695–703.

van Rooij IAJ. Serum anti-Mullerian hormone levels: a novel measure of ovarian reserve. Hum Reprod. 2002;17:3065–71.

Depmann M, Eijkemans MJC, Broer SL, Tehrani FR, Solaymani-Dodaran M, Azizi F, et al. Does AMH relate to timing of menopause? Results of an individual patient data meta-analysis. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2018;103:3593–600.

Schoenaker DA, Jackson CA, Rowlands JV, Mishra GD. Socioeconomic position, lifestyle factors and age at natural menopause: a systematic review and meta-analyses of studies across six continents. Int J Epidemiol. 2014;43:1542–62.

Sudlow C, Gallacher J, Allen N, Beral V, Burton P, Danesh J, et al. UK Biobank: an open access resource for identifying the causes of a wide range of complex diseases of middle and old age. PLoS Med. 2015;12:e1001779.

Zavos A, Valachis A. Risk of chemotherapy-induced amenorrhea in patients with breast cancer: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Acta Oncol. 2016;55:664–70.

Revilla M, Villa LF, Sanchez-Atrio A, Hernandez ER, Rico H. Influence of body mass index on the age-related slope of total and regional bone mineral content. Calcif Tissue Int. 1997. https://doi.org/10.1007/s002239900310.

Acknowledgements

Not applicable.

Funding

Not applicable.

Author information