Abstract

Background

Young people living with HIV(YPLWH) in low-and middle-income countries are entering adolescence and young adulthood in significant numbers. The majority of the HIV-related research on these young people has focused on clinical outcomes with less emphasis on their sexual and reproductive health (SRH). There is an increasing awareness of the importance of understanding and addressing their SRH needs, as many are at elevated risk of transmitting HIV to their sexual partners and young women, in particular, are at significant risk for transmitting HIV to their infants. The purpose of this scoping review is to synthesize research investigating the SRH needs of young people living with HIV in low- and middle-income countries.

Methods

We searched electronic databases for studies focusing on young people aged 10–24 years and 27 studies met inclusion criteria.

Results

This review identified four themes characterizing research on SRH among young people living with HIV: knowledge of SRH, access to SRH services, sexual practices, and future family planning and childrearing.

Conclusions

Our findings suggest a need for additional research on comprehensive sexuality education to equip YPLWH with knowledge to facilitate desirable SRH outcomes, interventions on sero-status disclosure and condom use, and health provider capacity to provide SRH services in their pre-existing HIV clinical care.

Plain Language summary

Young people living with HIV(YPLWH) in low-and middle-income countries are entering adolescence and young adulthood in large numbers. The majority of the HIV-related research on these young people has focused on clinical outcomes with less emphasis on their sexual and reproductive health. It is important to understand and address their sexual and reproductive health (SRH) needs, as many are at a high risk of passing on HIV to their sexual partners and young women, in particular, are at significant risk for passing on HIV to their infants. The purpose of this scoping review is to summarize research examining the SRH needs of young people living with HIV in low- and middle-income countries. We searched online databases for studies focusing on young aged 10–24 years and 27 studies were included in the review. This review identified four themes characterizing research on SRH among young people living with HIV: knowledge of SRH, access to SRH services, sexual practices, and future family planning and childrearing. Our findings suggest a need for additional research on comprehensive sexuality education to equip YPLWH with knowledge to facilitate desirable SRH outcomes, interventions on sero-status disclosure and condom use, and health provider capacity to provide SRH services in their pre-existing HIV clinical care.

Similar content being viewed by others

Background

The widespread success of highly active antiretroviral therapy (HAART) has improved the outlook and life expectancy of the nearly 3.4 million young people living with HIV worldwide [1]. While the majority of these young people (70%) were perinatally infected with HIV, the number of young people with behaviorally acquired HIV infection has increased overtime; in 2019, youth (aged 15–24 years) accounted for 28% of all new HIV infections, with adolescent girls and young women comprising up to two-thirds of new infections [1, 2]. HIV infection during adolescence and early adulthood poses a number of challenges to young people’s social and emotional development. Many young people living with HIV (YPLWH), for example, report difficulty establishing romantic relationships, experiences of stigma and discrimination, and fear the involuntary disclosure of their HIV status [3].

Considering that adolescence is characterized by a strong desire for autonomy and a rise in sexual expression and exploration [4], many YPLWH, like their peers without HIV, initiate sexual activity during this stage. Unfortunately, young people tend to have both low levels of sexual health knowledge and limited access to sexual and reproductive health (SRH) services, which are linked to higher engagement in sexual risk behaviors, unplanned pregnancies, and higher rates of sexually transmitted infections (STIs) [5, 6]. While these outcomes are concerning for all young people, the consequences are far more concerning for YPLWH, as they are at risk for transmitting the virus to their sexual partners and for young women, their infants, and experiencing worse health outcomes due to STI co-infection [7].

Though SRH has been identified as a research and health priority for young people, globally, many countries, including low and middle income countries (LMICs), have difficulty promoting SRH outcomes among young people [8, 9]. Structural and social barriers such as poverty, limited access to health services, and age of consent laws for accessing contraception and SRH services contribute to negative outcomes for young people in LMICs [10, 11]. For example, in comparison to their adult counterparts, young women from LMICs are at a greater risk for early pregnancy, unsafe abortions, and complications due to childbirth [12, 13]. YPLWH face an added burden of living with a stigmatized chronic condition that could impact their ability to access SRH services. Given the SRH challenges already impacting young people in LMICs, it is essential to understand how these challenges manifest in YPLWH in these countries. Understanding the unique SRH needs and identifying barriers to obtaining and accessing SRH services for YPLWH is necessary to support the development of comprehensive, youth friendly SRH interventions and services for this population. However, to date, we have limited research synthesizing the SRH needs of YPLWH from LMICs [10]. Published reviews have either focused on SRH needs of young people globally or SRH needs of young people in specific regions [8, 12, 14]. Therefore, in this article, we synthesize literature on the SRH needs of YPLWH in LMICs.

Methods

We followed the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses Guidelines (PRISMA). An electronic search was conducted in March 2020 of the following databases: PubMed, Scopus, and Web of Science. Search terms included ‘adolescent’, ‘youth’, ‘HIV’, ‘AIDS’ ‘sexual and reproductive health’, ‘sexual behavior’, ‘reproductive health’, ‘family planning’, and ‘maternal and child health’. Eligibility criteria included the following: (1) published in a peer-reviewed journal; (2) written in English; (3) focused on YPLWH aged 10–24 years; (4) reported results from a LMIC; and (5) explicitly discussed the sexual and reproductive health of YPLWH. We manually identified countries as LMIC based on the World Bank classifications in February 2020.

All three databases were searched by three independent reviewers (LM, MN, and JB). Titles and abstracts were read and evaluated based on the above inclusion criteria. Articles that met inclusion criteria based on the first review were included in a spreadsheet and uploaded to a shared reference manager. Articles that were identified by at least two independent reviewers automatically moved to the full text review. Articles were included in this scoping review if all three reviewers agreed on its inclusion. Discrepancies amongst reviewers were discussed with the research group until an agreement was achieved. This scoping review focused on primary sources; however, other types of reviews (e.g., systematic, scoping, or content reviews) that were identified during article extraction were reviewed manually for any mention of articles that did not appear in our electronic search.

Data from articles were abstracted and charted detailing the author(s), year of publication, country setting, aims and purpose of the research, methodology, study population, and key findings. A qualitative content analysis was conducted on the key findings to identify common themes across studies.

Results

Figure 1 presents the results of our study selection process. The initial search generated a total of 2114 titles and abstracts. After excluding duplicates and incomplete references, 1965 articles underwent title and abstract screening. Of these, 112 articles underwent full text review, and 85 articles did not meet inclusion criteria. The final sample consisted of 27 articles.

Sample characteristics

Table 1 describes the characteristics of included studies, which were published between 2004 and 2019. Twenty-two studies were conducted in sub-Saharan African countries: Uganda (n = 7), Zambia (n = 5), Kenya (n = 3), Tanzania (n = 2), South Africa (n = 2), Côte d’Ivoire (n = 2), Malawi (n = 1), and Zimbabwe (n = 1). The remaining five studies were conducted in Asian countries: China (n = 1), India (n = 1), and Thailand (n = 3). Twenty-three studies had a cross-sectional study design and 11 studies utilized qualitative methods.

Our review identified four themes characterizing SRH needs among YPLWH: knowledge of SRH, access to SRH services, sexual practices, and future family planning and childrearing. While the resulting studies were conducted in different countries and communities, the themes were consistent across geographical regions. We describe each theme in detail below.

Knowledge of sexual and reproductive health

Thirteen studies reported that YPLWH either had low SRH knowledge or limited access to information about SRH. Five studies showed that YPLWH lacked an understanding of how HIV affected their bodies, ways in which HIV and other STIs were transmitted, or had limited SRH knowledge [7, 15,16,17,18]. A study of YPLWH with perinatal HIV infection in China, for example, found that only 5% of enrolled young people were able to correctly answer questions about HIV, and only 18% of young people answered questions about contraception correctly [16]. In contrast, a knowledge, attitudes, and practices study in Thailand found that, while most young people could correctly answer questions about HIV transmission and antiretroviral therapy adherence, fewer than half demonstrated knowledge on family planning, reproductive health, and STIs [19].

Additionally, YPLWH reported that they did not know where to go to obtain information about SRH such as contraception [16, 20]. In contrast, YPLWH who did know where to obtain information reported discomfort discussing SRH with providers and sometimes avoided seeking services due to fear of being stigmatized or judged [21]. In a qualitative study in Tanzania, young people reported discomfort with discussing sex and sexuality with providers and caregivers, and also had limited access to information on reproductive health [22].

Access to reproductive health services

Four studies assessed maternal health and pregnancy among adolescent girls living with HIV [23,24,25,26]. These studies found that, while the incidence of unplanned pregnancies among adolescent girls living with HIV was similar to the incidence in adult cohorts in sub-Saharan Africa, utilization of prenatal care and participation in prevention of mother-to-child transmission (PMTCT) health services was lower among adolescent girls living with HIV [24]. These finding may partially explain the results of a study in South Africa suggesting that YPLWH have a higher likelihood of vertically transmitting HIV to their babies than their adult counterparts [25]. In addition to low engagement in prenatal care and PMTCT services, YPLWH in Côte d’Ivoire and Kenya, for example, also reported inconsistent post-partum contraception use, which has been linked to higher rates of unintended pregnancies within this population [23, 26].

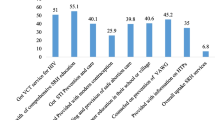

Provider characteristics were identified as barriers to accessing SRH services among YPLWH. We identified nine studies of healthcare providers and other health service delivery stakeholders that assessed their comfort, readiness, and/or competence to provide SRH to YPLWH. In four studies, providers reported low self-efficacy in their ability to provide SRH services such as contraception to YPLWH [18, 22, 27, 28]. Common reasons for low confidence were cultural barriers, gaps in knowledge about SRH needs of YPLWH, and having a limited number of healthcare providers available to offer comprehensive services. Other healthcare provider-related barriers included personal and often value-laden preferences for abstinence among young people, with some suggesting condom use as an alternative option for those were unable to abstain from sexual activity [21, 29]. Our review also identified the absence of clear policies to guide SRH service provision for YPLWH. A Ugandan study of key stakeholders from non-governmental organizations and bilateral organizations, for example, linked gaps in SRH policies for YPLWH to the absence of youth-friendly healthcare transition clinics and low provider and institutional capacity to provide these services [30].

Sexual practices

Collectively, findings from reviewed studies suggested that YPLWH engaged in sexual activities at rates that were similar to their peers without HIV [31]. Moreover, like their peers without HIV, YPLWH reported inconsistent condom use, with fewer than half reporting condom use during their last sexual encounter [32,33,34,35]. While the causes of inconsistent condom use within this population are multifactorial, a Ugandan study suggested that the fear of unintended consequences, such as pregnancy and contracting other STIs, motivated YPLWH to use condoms [15].

YPLWH also had the added burden of disclosing their HIV status to their sexual partners, which was often accompanied with fear of HIV-related stigma and rejection by sexual partners [22, 32]. Our review revealed that more than half of YPLWH reported low levels of HIV status disclosure to their sexual partners. Moreover, many of these young people were unaware of the HIV serostatus of their sexual partners [19, 20, 29, 32,33,34,35,36]. Two Ugandan studies of YPLWH reporting young people’s preferences for an HIV-negative partner due to fear of HIV re-infection [32, 33].

Future relationships and childbearing

Lastly, in four studies, concerns about future relationships and childbearing emerged as an SRH theme for YPLWH in LMICs. YPLWH reported desires to have children and be married in the future, but also expressed concerns with realizing these desires [35, 37, 38]. A Thai study, for example, suggested that YPLWH had lower expectations about family formation than their peers without HIV [39]. For many young people, these feelings were partially a result of messaging from caregivers and healthcare providers on the dangers of sexual intercourse and the importance of abstinence [35]. Additionally, YPLWH were less hopeful of future partnering due to the fear of disclosing their status to their partners and experiencing rejection and abandonment. This fear was often coupled with uncertainty about how to disclose their status to future intimate partners. Young people also expressed concerns about transmitting the virus to their sexual partners and children and reported low knowledge regarding how to prevent sexual transmission to others [35].

Discussion

This scoping review synthesized literature elucidating the sexual and reproductive health needs of YPLWH in LMICs. The review yielded 27 studies from 11 countries in sub-Saharan Africa and Asia. We identified four main sexual and reproductive health themes: knowledge of sexual and reproductive health, access to sexual and reproductive health services, sexual practices, and future relationships and childbearing. The findings from this review highlight specific gaps to be addressed in future research, policy, and programs in LMICs. First, there is a need for youth-friendly, sexual and reproductive health services for YPLWH in LMICs that integrate comprehensive sexuality education, which is characterized by open-mindedness, non-judgmental and positive attitudes by health providers. Second, there is a need for interventions that encourage young people to adopt safe sex behaviors, such as condom use, and prepare young people to disclose their HIV status to sexual partners.

Inadequate knowledge of sexual and reproductive health, contraceptive options, and family planning coupled with limited access to sexual reproductive health services was a common finding across the studies. This finding has important implications for the health outcomes of YPLWH, particularly as it relates to SRH for adolescent girls living with HIV. Generally, adolescent girls and young women in LMICs have an increased risk of acquiring HIV and having unintended pregnancies, unsafe abortions, and birth complications [8]. These risks are compounded for adolescent girls and young women living with HIV, as they are at increased risk of spontaneous abortions, pre-term delivery and delivering babies of low birth weight [40]. Additionally, these findings have implications for reducing mother to child transmission of HIV. Despite scale up of PMTCT services globally, rates of mother to child transmission have declined modestly in many LMICs (UNAIDS). In order to achieve gains in PMTCT, YPLWH and especially adolescent girls and young women living with HIV must receive comprehensive sexual and reproductive health knowledge and services.

Our findings showed that YPLWH engage in sexual encounters at similar rates to young people not living with HIV, and YPLWH desire to be in relationships and have families. Interestingly, in two studies YPLWH reported a preference for romantic and/or sexual partners without HIV [32, 33]. This is potentially problematic, as HIV status disclosure to sexual partners was relatively low among YPLWH in the study cohorts and many were unaware of their partner’s HIV status [20, 33, 34]. YPLWH have a right to desire partnership with any person regardless of the person’s sero-status; however, low rates of disclosure and inconsistent condom use puts their partners and themselves at risk for HIV reinfection, STI co-infection, and HIV transmission. HIV sero-status disclosure is a key component in reducing HIV transmission; however, fear of stigma, violence, and rejection pose as obstacles for YPLWH. These findings point to an urgent need to implement disclosure related interventions targeted towards YPLWH. These interventions should include education on consistent condom use,comprehensive counseling on disclosure and negotiating safe sex practices with partners, and the importance of maintaining an undetectable viral load to prevent HIV transmission [3].

Lastly, findings from this review highlight the gap in health provider capacity to provide SRH services to YPLWH. Providers preferred abstinence-based SRH education and counseling. However, given that YPLWH continue to be sexually active despite receiving abstinence-based counseling and messaging, this demonstrates that health providers are not responding adequately to the needs of YPLWH. Lack of training in adolescent psychosocial development and the unique SRH needs of YPLWH has been linked to poor quality of care and low motivation to engage in SRH services by YPLWH [18, 22, 27, 28]. These results support the need for clear guidelines on providing SRH services to YPLWH along with additional training for health providers to adequately respond to the needs of this population [28, 30]. These trainings should address providers’ attitudes and belies on young people’s sexuality, and sensitize providers to the needs and rights of young people.

This review indicated that there are a few published interventions aimed at improving SRH among YPLWH in LMICs [41]. We identified two interventions that integrated comprehensive sexual and reproductive health services with HIV care, which resulted in greater SRH knowledge among YPLWH and a significant increase in the uptake of SRH services [7, 42]. Providing youth-friendly services that are incorporated with HIV services is a promising method of improving knowledge and access to SRH for YPLWH in LMICs. Youth-friendly services, for example, may create an acceptable, equitable, and confidential environment for YPLWH to receive the SRH care that they require [43]. Youth-friendly services should also offer comprehensive sexuality education to equip YPLWH with adequate knowledge to make informed decisions. Comprehensive sexual education provides young people with information regarding anatomy but also empowers them to adopt healthy sexual habits [9]. As YPLWH transition into adulthood and explore their sexual and relationship desires, it is important to provide them with the resources and tools necessary to navigate aspects of their lives that are both directly and indirectly linked to their SRH, which will include coping skills necessary to live with a stigmatized chronic condition that impacts their romantic and sexual outlook, family planning, and preparation for disclosing their serostatus to intimate partners.

This study is not without limitations. First, we limited our search to the three most well-utilized databases in public health and HIV research. As such, it is possible that some studies may have been missed and not included in this review. Nonetheless, a scoping review is not meant to be a systematic assessment of the literature on a specific topic. Instead, they are best utilized when topics are constantly evolving, as is the case of SRH among YPLWH in LMICs. Second, results were limited to studies published in English and may have led to a language bias. Third, the studies focused on YPLWH in SSA countries and a few countries in Asia. As a result, it is possible that these findings may not be generalizable for YPLWH outside of these settings. Despite these limitations, the findings in this review add to the growing body of knowledge on the unique SRH challenges of YPLWH. To the best of our knowledge, this is the first scoping review that has documented the SRH needs of YPLWH in LMICs [44,45,46].

Conclusion

As YPLWH begin to transition to adulthood, they face the compounded burden of navigating a stigmatized, chronic condition while also experiencing the rapid physiological and sexual development characteristic of adolescence and young adulthood. While sexual and reproductive health is a key component of this developmental stage, additional research was needed to synthesize the unique SRH needs of YPLWH in LMICs. Our findings suggest a need for additional research on comprehensive sexuality education to equip YPLWH with knowledge to facilitate desirable SRH outcomes, interventions on sero-status disclosure and condom use, and health provider capacity to provide SRH services in their pre-existing HIV clinical care.

Availability of data and materials

Data sharing is not applicable as no new datasets were generated or analyzed during the conduct of this review.

Code availability

Not applicable.

Abbreviations

- HAART:

-

Highly active antiretroviral therapy

- LMICs:

-

Low and middle income countries

- PMTCT:

-

Prevention of mother-to-child transmission

- PRISMA-c:

-

Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses

- SRH:

-

Sexual and reproductive health

- STIs:

-

Sexually transmitted infections

- YPLWH:

-

Young people living with HIV

References

UNICEF. Adolescent HIV prevention [Internet]. UNICEF DATA. 2019 [cited 2020 Feb 29]. https://data.unicef.org/topic/hivaids/adolescents-young-people/.

UNAIDS. Young people and HIV. 2021;20.

Toska E, Cluver LD, Hodes R, Kidia KK. Sex and secrecy: how HIV-status disclosure affects safe sex among HIV-positive adolescents. AIDS Care. 2015;27:47–58.

Patton GC, Viner RM, Linh LC, Ameratunga S, Fatusi AO, Ferguson BJ, et al. Mapping a global agenda for adolescent health. J Adolesc Health Off Publ Soc Adolesc Med. 2010;47:427–32.

Comins CA, Rucinski KB, Baral S, Abebe SA, Mulu A, Schwartz SR. Vulnerability profiles and prevalence of HIV and other sexually transmitted infections among adolescent girls and young women in Ethiopia: a latent class analysis. PLoS ONE. 2020;15:e0232598.

Morris JL, Rushwan H. Adolescent sexual and reproductive health: the global challenges. Int J Gynecol Obstet. 2015;131:S40–2.

Vu L, Burnett-Zieman B, Banura C, Okal J, Elang M, Ampwera R, et al. Increasing uptake of HIV, sexually transmitted infection, and family planning services, and reducing HIV-related risk behaviors among youth living with HIV in Uganda. J Adolesc Health. 2017;60:S22–8.

Santhya KG, Jejeebhoy SJ. Sexual and reproductive health and rights of adolescent girls: evidence from low- and middle-income countries. Glob Public Health. 2015;10:189–221.

UNESCO, UNAIDS, UNFPA, UNICEF, WHO. Young people today, time to act now: why adolescents and young people need comprehensive sexuality education and sexual and reproductive health services in Eastern and Southern Africa; summary.

Chandra-Mouli V, McCarraher DR, Phillips SJ, Williamson NE, Hainsworth G. Contraception for adolescents in low and middle income countries: needs, barriers, and access. Reprod Health. 2014;11:1.

Mmari K, Astone N. Urban adolescent sexual and reproductive health in low-income and middle-income countries. Arch Dis Child. 2014;99:778–82.

Chandra-Mouli V, Armstrong A, Amin A, Ferguson J. A pressing need to respond to the needs and sexual and reproductive health problems of adolescent girls living with HIV in low- and middle-income countries. J Int Aids Soc. 2015;18:83–7.

Shah IH, Åhman E. Unsafe abortion differentials in 2008 by age and developing country region: high burden among young women. Reprod Health Matters. 2012;20:169–73.

Ajayi AI, Okeke SR. Protective sexual behaviours among young adults in Nigeria: influence of family support and living with both parents. BMC Public Health. 2019;19:983.

Bakeera-Kitaka S, Nabukeera-Barungi N, Nöstlinger C, Addy K, Colebunders R. Sexual risk reduction needs of adolescents living with HIV in a clinical care setting. AIDS Care Psychol Socio-Med Asp AIDSHIV. 2008;20:426–33.

Mu W, Zhao Y, Khoshnood K, Cheng Y, Sun X, Liu X, et al. Knowledge and perceptions of sexual and reproductive health and HIV among perinatally HIV-infected adolescents in rural China. AIDS Care. 2015;27:1137–42.

Ngilangwa DP, Rajesh S, Kawala M, Mbeba R, Sambili B, Mkuwa S, et al. Accessibility to sexual and reproductive health and rights education among marginalized youth in selected districts of Tanzania. Pan Afr Med J. 2016;25:2.

Vujovic M, Struthers H, Meyersfeld S, Dlamini K, Mabizela N. Addressing the sexual and reproductive health needs of young adolescents living with HIV in South Africa. Child Youth Serv Rev. 2014;45:122–8.

Lolekha R, Boon-Yasidhi V, Leowsrisook P, Naiwatanakul T, Durier Y, Nuchanard W, et al. Knowledge, attitudes, and practices regarding antiretroviral management, reproductive health, sexually transmitted infections, and sexual risk behavior among perinatally HIV-infected youth in Thailand. AIDS Care Psychol Socio-Med Asp AIDSHIV. 2015;27:618–28.

Ndongmo TN, Ndongmo CB, Michelo C. Sexual and reproductive health knowledge and behavior among adolescents living with HIV in Zambia: a case study. Pan Afr Med J. 2017;26.

Mwalabu G, Evans C, Redsell S. Factors influencing the experience of sexual and reproductive healthcare for female adolescents with perinatally-acquired HIV: a qualitative case study. BMC Womens Health. 2017;17:125.

Busza J, Besana GVR, Mapunda P, Oliveras E. “I have grown up controlling myself a lot.” Fear and misconceptions about sex among adolescents vertically-infected with HIV in Tanzania. Reprod Health Matters. 2013;21:87–96.

Arikawa S, Eboua T, Kouakou K, N’Gbeche M-S, Amorissani-Folquet M, Moh C, et al. Pregnancy incidence and associated factors among HIV-infected female adolescents in HIV care in urban Côte d’Ivoire, 2009–2013. Glob Health Action. 2016;9:31622.

Birungi H, Obare F, van der Kwaak A, Namwebya JH. Maternal health care utilization among HIV-positive female adolescents in Kenya. Int Perspect Sex Reprod Health. 2011;37:143–9.

Horwood C, Butler LM, Haskins L, Phakathi S, Rollins N. HIV-infected adolescent mothers and their infants: low coverage of HIV services and high risk of HIV transmission in KwaZulu-Natal, South Africa. PLoS One. 2013;8.

Obare F, van der Kwaak A, Birungi H. Factors associated with unintended pregnancy, poor birth outcomes and post-partum contraceptive use among HIV-positive female adolescents in Kenya. BMC Womens Health. 2012;12:34.

Hodgson I, Ross J, Haamujompa C, Gitau-Mburu D. Living as an adolescent with HIV in Zambia-lived experiences, sexual health and reproductive needs. AIDS Care Psychol Socio-Med Asp AIDSHIV. 2012;24:1204–10.

Mburu G, Hodgson I, Teltschik A, Ram M, Haamujompa C, Bajpai D, et al. Rights-based services for adolescents living with HIV: adolescent self-efficacy and implications for health systems in Zambia. Reprod Health Matters. 2013;21:176–85.

McCarraher DR, Packer C, Mercer S, Dennis A, Banda H, Nyambe N, et al. Adolescents living with HIV in the copperbelt province of Zambia: their reproductive health needs and experiences. PLoS One. 2018;13.

Obare F, Birungi H, Kavuma L. Barriers to sexual and reproductive health programming for adolescents living with HIV in Uganda. Popul Res Policy Rev. 2011;30:151–63.

Loos J, Nöstlinger C, Murungi I, Adipo D, Amimo B, Bakeera-Kitaka S, et al. Having sex, becoming somebody: a qualitative study assessing (sexual) identity development of adolescents living with HIV/AIDS. Vulnerable Child Youth Stud. 2013;8:149–60.

Ankunda R, Atuyambe LM, Kiwanuka N. Sexual risk related behaviour among youth living with HIV in central Uganda: implications for HIV prevention. Pan Afr Med J [Internet]. 2016;24. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC5012777/.

Birungi H, Mugisha JF, Obare F, Nyombi JK. Sexual behavior and desires among adolescents perinatally infected with human immunodeficiency virus in Uganda: implications for programming. J Adolesc Health. 2009;44:184–7.

Mbalinda SN, Kiwanuka N, Eriksson LE, Wanyenze RK, Kaye DK. Correlates of ever had sex among perinatally HIV-infected adolescents in Uganda. Reprod Health. 2015;12:96.

Okawa S, Mwanza-Kabaghe S, Mwiya M, Kikuchi K, Jimba M, Kankasa C, et al. Sexual and reproductive health behavior and unmet needs among a sample of adolescents living with HIV in Zambia: a cross-sectional study. Reprod Health. 2018;15:55.

Zamudio-Haas S, Mudekunye-Mahaka I, Lambdin BH, Dunbar MS. If, when and how to tell: a qualitative study of HIV disclosure among young women in Zimbabwe. Reprod Health Matters. 2012;20:18–26.

Dago-Akribi HA, Adjoua MCC. Psychosexual development among HIV-positive adolescents in Abidjan, Cote d’Ivoire. Reprod Health Matters. 2004;12:19–28.

Vranda MN, Subbakrishna DK, Ramakrishna J, Veena HG. Sexual and reproductive health concerns of adolescents living with perinatally infected HIV in India. Indian J Community Med Off Publ Indian Assoc Prev Soc Med. 2018;43:239–42.

Rolland-Guillard L, de La Rochebrochard E, Sirirungsi W, Kanabkaew C, Breton D, Le Coeur S. Reproductive health, social life and plans for the future of adolescents growing-up with HIV: a case-control study in Thailand. Aids Care-Psychol Socio-Med Asp AidsHiv. 2019;31:90–4.

Agwu AL, Jang SS, Korthuis PT, Araneta MRG, Gebo KA. Pregnancy incidence and outcomes in vertically and behaviorally HIV-infected youth. JAMA. 2011;305:468–70.

Pretorius L, Gibbs A, Crankshaw T, Willan S. Interventions targeting sexual and reproductive health and rights outcomes of young people living with HIV: a comprehensive review of current interventions from sub-Saharan Africa. Glob Health Action. 2015;8:28454.

Landolt NK, Achalapong J, Kosalaraksa P, Petdachai W, Ngampiyaskul C, Kerr S, et al. Strategies to improve the uptake of effective contraception in perinatally. J Virus Erad. 2017;3:152–6.

Adolescent-friendly health services for adolescents living with HIV: from theory to practice [Internet]. [Cited 2020 May 25]. https://www.who.int/publications-detail/adolescent-friendly-health-services-for-adolescents-living-with-hiv.

Armstrong A, Nagata JM, Vicari M, Irvine C, Cluver L, Sohn AH, et al. A global research agenda for adolescents living with HIV. J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr. 1999;2018(78 Suppl 1):S16-21.

Folayan MO, Harrison A, Odetoyinbo M, Brown B. Tackling the sexual and reproductive health and rights of adolescents living with HIV/AIDS: a priority need in Nigeria. Afr J Reprod Health. 2014;18:102–8.

Hamzah L, Hamlyn E. Sexual and reproductive health in HIV-positive adolescents. Curr Opin HIV AIDS. 2018;13:230–5.

Acknowledgements

Not applicable.

Funding

TR’s effort was supported by: (1) career development awards from the Duke Center for Research to Advance Healthcare Equity (REACH Equity), which is supported by the National Institute on Minority Health and Health Disparities under award number U54MD012530 and the National Institute of Mental Health (K08MH118965); (2) training Grants from the National Institute on Drug Abuse (R25DA035692) and the UJMT Global Consortium (D43TW009340); and (3) other support from the Duke University Center for AIDS Research (CFAR), an NIH funded program (5P30 AI064518). The content of this article is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the National Institutes of Health.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

LM and TR conceptualized the review. LM, MN, and JB conducted the literature rereview and analysis. LM wrote the first draft, and all authors critically revised previous versions. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate

Not applicable.

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Competing interests

All authors report no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/. The Creative Commons Public Domain Dedication waiver (http://creativecommons.org/publicdomain/zero/1.0/) applies to the data made available in this article, unless otherwise stated in a credit line to the data.

About this article

Cite this article

Mkumba, L.S., Nassali, M., Benner, J. et al. Sexual and reproductive health needs of young people living with HIV in low- and middle-income countries: a scoping review. Reprod Health 18, 219 (2021). https://doi.org/10.1186/s12978-021-01269-7

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/s12978-021-01269-7