Abstract

Background

Menstrual irregularity is a common problem among women aged from 21 to 25 years. Previously published work on menstrual irregularity used inconsistent definition which results in a difference in prevalence. Therefore the study aimed to assess the magnitude and associated factors of menstrual irregularity among undergraduate students of Debre Berhan University, Ethiopia.

Methods

A cross-sectional study design was carried out among 660 undergraduate female students at Debre Berhan University. To get representative study participants, a stratified sampling technique was used. To collect the data self-administered questionnaire was used. Physical examination and anthropometric measurement were also done. Data were analyzed by using SPSS version 21. Logistic regression analysis was done. A significant association was declared at a p-value less than 0.05.

Result

A total of 620 students participated in the present study with a response rate of 93.9%. Out of the total study participants, 32.6% (95% CI 29–36.5) participants had irregular menstrual cycle. Significant association was found between anemia (AOR = 2.1; 95%CI 1.337–3.441), alcohol intake (AOR = 2.4; 95%CI 1.25–4.666), < 5 sleep hours (AOR = 5.4; 95%CI 2.975–9.888), 6–7 sleep hours (AOR = 1.9; 95%CI 1.291–2.907), Perceived stress (AOR = 3.3; 95%CI 1.8322–5.940), iodine deficiency disorder (IDD) (AOR = 3.9; 95%CI 1.325–11.636) and underweight (AOR = 1.8; 95%CI 1.109–2.847) with menstrual irregularity.

Conclusion

The finding of this study reported a low magnitude of menstrual irregularity as compared to previous studies. Students should adopt healthier lifestyle practices (weight control, stress control, anemia control, and avoid alcohol intake) to control menstrual irregularity.

Plain language summary

Menstrual irregularity is a common problem among university students. It affects their daily activities. But it lacks attention, especially in developing countries. Additionally, menstrual irregularity is defined differently by different researchers which results in a difference in prevalence. So it is difficult to compare. Therefore this study aims to assess the magnitude and associated factors of menstrual irregularity among undergraduate students of Debre Berhan University, Ethiopia. To avoid the inconsistent definition of menstrual irregularity which is used by different researchers, we used the standard of menstrual irregularity definition which was prepared by the international federation of obstetrics and gynecologist in 2018.

This study uses across sectional study design among 660 undergraduate students of Debre Berhan University, Ethiopia. A self-administered questioner which includes socio-demographic data, menstrual-related questions, lifestyle and behavioral questions, and medical history questions were used to collect data. Besides, physical examination and anthropometric measurement were done.

Of a total 620 students who participated in the study: 202 (32.6%) had menstrual irregularity. Factors that had significant association with menstrual irregularity were, anemia (AOR = 2.1; 95%CI 1.337–3.441), alcohol intake (AOR = 2.4; 95%CI 1.25–4.666), < 5 sleep hours (AOR = 5.4; 95%CI 2.975–9.888), 6–7 sleep hours (AOR = 1.9; 95%CI 1.291–2.907), Perceived stress (AOR = 3.3; 95%CI 1.8322–5.940), iodine deficiency disorder (IDD) (AOR = 3.9; 95%CI 1.325–11.636) and underweight (AOR = 1.8; 95%CI 1.109–2.847). In conclusion, the finding of this study reported a low magnitude of menstrual irregularity as compared to previous studies.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Menstruation is a physiological process and all women have to go through it for a major part of their life. But problems come related to it, which at most of the time paid little attention [1]. According to a previous study regular menstrual cycle (counting from the first day of one menstrual period to the first day of the next cycle) is 21 to 35 days and lasts from 3 to 7 days duration with a volume of blood loss of 5–80 ml [2]. Otherwise, menstrual irregularity refers to any kind of changes occurring irregularity of onset, frequency of onset, duration of flow, and volume from the regular menstrual cycle [3,4,5]. The regular cycle at puberty depends on a complex series of interactions involving the hypothalamus, anterior pituitary, and ovaries. Interruption of the hypothalamic-pituitary-ovarian (HPO) axis pathway results in an irregular menstrual cycle [6].

Many problems tackle the quality of life and academic performance of female students. From these, menstrual cycle irregularity is a major gynecological problem and a source of anxiety to them and their families [2]. It influences the different daily activities of students [1, 7]. Moreover, studies revealed that menstrual irregularity has also a longer impact on later life, such as osteoporosis, infertility, future diabetes mellitus (DM), and cardiovascular disease (CVD) [2, 8, 9].

It is most prevalent in the 21–25 years age group (85%) [10]. According to studies conducted in India, the prevalence of menstrual irregularity was 35.7% and 23.3%, respectively [4, 11]. Besides, other studies in Asia revealed an even high (64.2% and 38.7%) prevalence of menstrual irregularity [12, 13]. Moreover, an Egyptian study revealed a prevalence of 33.3% [14]. Studies reported that anemia, stress, genetic factors, and nutritional habit are major contributing factors for menstrual irregularity [15, 16].

Previously published work on menstrual irregularity used inconsistent definition which results in a difference in prevalence. Additionally, there is no previous study on menstrual irregularity among university students in Ethiopia which may be different from other countries due to socio-demographic, nutrition, and genetic factors. Therefore, this study aimed to assess the magnitude of menstrual irregularity by using the standard of menstrual irregularity definition which was prepared by the international federation of gynecology and obstetrics (FIGO) menstrual recommendations on terminologies and definitions for normal and abnormal uterine bleeding in 2011 and revised 2018 [17, 18].

Methods and materials

Study design, settings, and participants

An institutional-based cross-sectional study design was conducted at Debre Berhan University from February 11 to March 10 /2020. During the study period, the total population of the study area was 5387. Among them 4009 students were regular and 1378 were extension. Undergraduate regular students who were pregnant, who were within one year after delivery and lactating, who had a treatment history for menstrual irregularity during the year of study, and who were critically ill during the data collection period were excluded from the study.

Sample size and sampling procedures

The sample size was calculated using a formula for estimation of single population proportion with the assumption of 95% confidence interval, 4% margin of error, and prevalence of menstrual irregularity as 50%. To compensate for the non-response rate, 10% of the determined sample was added upon the calculated sample size, and the final sample size was found to be 660. To get a representative sample stratified sampling technique was used. First, all undergraduate regular students were stratified by academic year (1st, 2nd, 3rd year, and above). Finally, the required sample size of study subjects was selected by using a proportionally allocated random table method.

Data collection procedures

A pretested self-administered questioner was used to collect the data. Also, physical examination and anthropometric measurements were done. The questionnaire includes socio-demographic data, menstrual-related questions, lifestyle and behavioral questions, medical history questions, anthropometric measurements (height and weight), and physical examination of the thyroid gland.

The questionnaire was first prepared in English language and then translated into the Amharic language. A person who was an expert in both languages checked the questionnaires' consistency. Besides, a panel of experts has ascertained to assure the validity of socio-demographic, menstrual cycle pattern, and medical questions. They checked the tools for content validity, completeness, and clarity. Finally, their comments were considered.

Outcome

Whether the menstrual cycle is regular or irregular should be determined by using standards of menstrual irregularity definition which were prepared by the international federation of gynecology and obstetrics (IFGO) 2018. Therefore, in the present study regular menstrual cycle was defined as if the frequency of menses is 24–38 days, duration of bleeding less than or equal to 8 days, cycle to cycle variation over the last one year be less than 10 days, and if the individual perception on the amount is normal [18]. On the other hand, menstrual irregularity refers to anything outside the regular menstrual cycle limit.

Predictors

Height was measured in meters and weight was recorded close to 100 g (least count of electronic weighing scale = 100 g). BMI is defined as the ratio of weight (kg) to height square (m2). Based on the calculated BMI the study participants were classified as underweight (BMI < 18.5), normal weight (BMI 18.5–24.9), overweight (BMI 25–29.9), and obese (BMI ≥ 30) [19]. Iodine deficiency disorder was assessed by measuring the size of the thyroid gland. It was graded according to the world health organization (WHO) criteria [20]. Then, the total goiter was calculated by adding grades 1 and 2. Anemia was assessed by the previous history of diagnosed anemia.

Perceived stress was measured with the Perceived Stress Scale (PSS). PSS is a 7-item multiple-choice self-report psychological instrument for measuring the perception of stress. Each answer was scored 0 to 3. PSS is scored by summing across all scale items. The total score ranges 0.0–21.0 (mean = 13.7(± 6.6) The cut-off values for stress limit were set at 15 [21]. Physical activity was collected by using the international physical activity questionnaire short form (IPAQs) [22]. It has three domain questions (vigorous activity, moderate activity, and walk). Alcohol intake was also collected by using the WHO alcohol use disorder identification test [23]. Each answer was scored 0 to 4. It is scored by summing across all scale items. The total score ranges 0.0–40.0 with a score greater than or equal to 4 indicating a high alcohol intake level.

Data analysis

Epi-data version 3.1 was used for data entry and exported to SPSS version 21 software for analysis. Normality test, model fitness test, multicollinearity test, and homogeneity of variance test were done. Descriptive statistics such as frequency and percentage were computed for categorical variables. Continuous variables were presented as mean ± standard deviation or median. To assess the association of different independent variables with the outcome variable, bivariate, and multivariable logistic regression analyses were carried out. A significant association was declared by odds ratio with 95% CI at a p-value less than 0.05.

Result

Socio-demographic characteristics

Of the total 660 study subjects, 620 of them completed the questionnaire. This makes the response rate of 93.9%. Their age ranges between 18 and 26 years with a mean age of 20.6 ± 1.4 years. The majority 323 (52.1%) of the respondents came from urban and 297 (47.9%) were from the rural areas. Most study participants 514 (82.9%) were Orthodox Christian followers (Table 1).

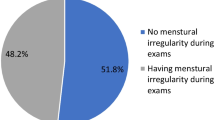

Prevalence of menstrual irregularity

Out of the total study participants, 418 (67.4%) participants had regular menstruation and 202 (32.6%) (95% CI 29–36.5) participants had irregular menstruation. Among menstrual irregularities, irregular onset was the major problem 123 (19.8%) (Table 2).

Risk factors associated with menstrual irregularity

Factors that were significantly associated with menstrual irregularity were a history of diagnosed anemia, alcohol intake, sleep hour, perceived stress, IDD, and BMI (Tables 3 and 4).

Discussion

According to this study, 32.6% (95% CI 29–36.5) of students had irregular menstruation. In the literature, the prevalence of irregular menstruation varies from 23.3 to 84.8% [10, 11, 13, 24].

The possible reasons for this variability are differences in the definition of irregular menstruation used by researchers. On the other hand, the difference may occur due to Indian study exclude students who were married, taking a hormonal contraceptive, and students who had medical problems) [11]. Additionally, different studies reported that genetic, socio-economic, and nutritional status determines the regularity of the menstrual cycle [25,26,27].

Concerning stress, this study showed that a high level of perceived stress was associated with menstrual irregularity. This finding is supported by a study conducted in Saudi Arabia which demonstrated that 80.9% of students had menstrual changes during an exam [28]. Moreover, a study conducted in China revealed that students who had high stress were correlated with menstrual irregularity [29]. On the contrary, an Indian study found no association between high stress with menstrual irregularity [30]. This could probably be due to the Indian study did not consider other factors that affect menstrual irregularity.

A theory explains the mechanism through which stress affects the menstrual cycle. When the stress level is high, the HPA axis activity is interrupted. Thus, women who are suffering from high stress may experience more irregularities in menstruation than those who are not under stress [31].

In this study, the association between high alcohol intake levels and menstrual irregularity was found to be significant. This is evidenced by a study conducted in China, those who drink regularly were more likely to report heavy periods compared with never drinkers [32]. On the contrary, no association was found among a cohort study conducted in the New York [33]. However, this study result is difficult to compare with the New York study because the latter only assessed acute alcohol consumption (alcohol exposure within two months duration) using a 24-h dietary recall method and dichotomous levels of alcohol consumption (< 4 and ≥ 4 drinks/day).

Recent evidence indicates that alcohol intake elevates the level of testosterone, estrogen, and luteinizing hormone in premenopausal women [34]. In turn, such hormonal imbalance may result in menstrual irregularity, which suggests biological plausibility for the association between alcohol drinking and menstrual irregularity.

A short sleeping hour was the third factor since the issue of sleep problems is significantly escalated during university. According to this study menstrual irregularity was more observed in students who slept ≤ 7 h per day. This is in line with a study conducted in Korea which revealed that subjects who slept ≤ 7 h per day were significantly associated with menstrual irregularity compared with those who slept for ≥ 8 h per day [5]. This is due to normal circadian rhythmicity and sleeps awake disruption which regulates the secretion of hormones (melatonin, cortisol, thyroid-stimulating hormone, and prolactin). As a result, menstrual irregularity may occur [35].

In this study, underweight students were around two times higher to develop menstrual irregularity as compared to normal weight. But there was no significant association between menstrual irregularity and overweight. On the contrary, studies conducted in Egypt and India revealed that obese and overweight girls were more frequently have irregular menstruation than normal and underweight girls [11, 36]. On the other hand, an Indian study showed that a high prevalence of irregular menstruation was observed on both overweight and underweight [37].

Moreover, an Indonesian study revealed that no relationship between body mass index (BMI) and menstrual interval and amount [38]. This may be due to there were no enough overweight (8.4%) or obese (1%) students in this study as compared to others.

Anemia is the major nutritional deficiency found in this age group where 18.4% of students had a history of diagnosed anemia. The result of this study demonstrated that there was a significant association b/n anemia and menstrual irregularity. This is in line with studies conducted in India and Bangladesh [39,40,41].

On the other hand, this study found that menstrual irregularity was associated with goiter or IDD. In line with this, a study conducted in Russia indicated that menstrual disorder was more observed among students who had iodine deficiency [42]. This is due to the role of iodine in the synthesis of thyroid hormones [43]. Thyroid hormones directly affecting the ovaries and indirectly interacting with sex hormone-binding globulin [44]. This contributes to the understanding of the relationship between iodine and menstrual irregularity. The limitation of this study was the cross-sectional nature of data that could obscure the causal effect of different factors and recall bias may be present.

Conclusion

The magnitude of menstrual irregularity in DBU regular students was low as compared to previous studies in Afghanistan, Egypt, and Saudi. But it is higher relative to study done in India.

The result of this study suggested that healthier lifestyle practices, including, weight control, stress control, anemia control, and avoid alcohol intake were important factors in controlling menstrual irregularity. Therefore Students should adopt healthier lifestyle practices to control menstrual irregularity and to reduce the effect of menstrual irregularity on academic performance. IDD mostly assessed on primary school students. It lacks attention on university students. According to this study finding, 3.1% of students had a goiter. So, further research is required to determine the prevalence of IDD on university students and its effect.

Availability of data and materials

The datasets used and/or analyzed during the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

Abbreviations

- IDD:

-

Iodine deficiency disorder

- CI:

-

Confidence interval

- OR:

-

Odds ratio

- DBU:

-

Debre Berhan University

- BMI:

-

Body Mass Index

- DM:

-

Diabetes mellitus

- CVD:

-

Cardiovascular disease

- IFGO:

-

International Federation of Gynecologists and Obstetrics

- IPAQs:

-

International Physical Activity Questionnaire short form

- PSS:

-

Perceived Stress Scale

- WHO:

-

World Health Organization

References

Kadir R, Edlund M, Von Mackensen S. The impact of menstrual disorders on quality of life in women with inherited bleeding disorders. Haemophilia. 2010;16(5):832–9.

West S, Lashen H, Bloigu A, Franks S, Puukka K, Ruokonen A, et al. Irregular menstruation and hyperandrogenaemia in adolescence are associated with polycystic ovary syndrome and infertility in later life: Northern Finland Birth Cohort 1986 study. Hum Reprod. 2014;29(10):2339–51.

Gersak K, Gersak Z. Chromosomal abnormalities and menstrual cycle disorders. 2017.

Kumar A, Seshadri JG, Murthy N. Correlation of anthropometry and nutritional assessment with menstrual cycle patterns. J SAFOG. 2018;10:263–9.

Nam GE, Han K, Lee G. Association between sleep duration and menstrual cycle irregularity in Korean female adolescents. Sleep Med. 2017;35:62–6.

Gray SH. Menstrual disorders. Pediatr Rev. 2013;34(1):6–18.

Gujarathi J, Jani D, Murthi A. Prevalence of menstrual disorders in hostellers and its effect on education—a cross sectional study. World J Pharmaceut Res. 2014;3:4060–5.

Rostami Dovom M, Ramezani Tehrani F, Djalalinia S, Cheraghi L, Behboudi Gandavani S, Azizi F. Menstrual cycle irregularity and metabolic disorders: a population-based prospective study. PLoS ONE. 2016;11(12):e0168402.

Solomon CG, Hu FB, Dunaif A, Rich-Edwards JE, Stampfer MJ, Willett WC, et al. Menstrual cycle irregularity and risk for future cardiovascular disease. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2002;87(5):2013–7.

Aber A. Prevalence of menstrual disturbances among female students of fourth and fifth classes of curative medicine faculty. IJRDO—J Health Sci Nurs. 2018;3(4):1–14.

Deborah SG, Priya SD, Swamy RC. Prevalence of menstrual irregularities in correlation with body fat among students of selected colleges in a district of Tamil Nadu, India. Natl J Physiol Pharm Pharmacol. 2017;7(7):740.

Sharma S, Deuja S, Saha C. Menstrual pattern among adolescent girls of Pokhara Valley: a cross sectional study. BMC Womens Health. 2016;16(1):1–6.

Thapa B, Shrestha T. Relationship between Body Mass Index and menstrual irregularities among the adolescents. Int J Nurs Res Pract. 2015;2(2):1324–2350.

Abdella N, Abd-Elhalim EHN, Attia AMF. The body mass index and menstrual problems among adolescent students. IOSR J Nurs Health Sci. 2016;5(4):1959–2320.

Jansen E, Herrán O, Fleischer N, Mondul A, Villamor E. Age at menarche in relation to prenatal rainy season exposure and altitude of residence: results from a nationally representative survey in a tropical country. J Dev Origins Health Dis. 2017;8(2):188–95.

Juliyatmi RH, Handayani L. Nutritional status and age at Menarche on female students of junior high school. Int J Eval Res Educ. 2015;4(2):71–5.

Fraser IS, Critchley HO, Broder M, Munro MG, editors. The FIGO recommendations on terminologies and definitions for normal and abnormal uterine bleeding. Semin Reprod Med. 2011. https://doi.org/10.1055/s-0031-1287662.

Munro MG, Critchley HO, Fraser IS, Committee FMD, Haththotuwa R, Kriplani A, et al. The two FIGO systems for normal and abnormal uterine bleeding symptoms and classification of causes of abnormal uterine bleeding in the reproductive years: 2018 revisions. Int J Gynecol Obstet. 2018;143(3):393–408.

Cashin K, Oot L. Guide to anthropometry: a practical tool for program planners, managers, and implementers. Food Nutr Tech Assist III Proj (FANTA)/FHI. 2018;360:93–115.

Organization WH. Goitre as a determinant of the prevalence and severity of iodine deficiency disorders in populations. World Health Organization; 2014.

Cohen S. Perceived stress in a probability sample of the United States. 1988.

Questionnaires IPA. International Physical Activity Questionnaires IPAQ: Short Last 7 Days Self-Administered Format. 2002.

Babor TF, Higgins-Biddle JC, Saunders JB, Monteiro MG. The alcohol use disorders identification test: World Health Organization Geneva; 2001.

Karout N. Prevalence and pattern of menstrual problems and relationship with some factors among Saudi nursing students. J Nurs Educ Pract. 2015;5(12):1–8.

Dars S, Sayed K, Yousufzai Z. Relationship of menstrual irregularities to BMI and nutritional status in adolescent girls. Pak J Med Sci. 2014;30(1):141.

Kwak Y, Kim Y, Baek KA. Prevalence of irregular menstruation according to socioeconomic status: a population-based nationwide cross-sectional study. PLoS ONE. 2019;14(3):e0214071.

Said AR, Mettwaly MG. Improving life style among nursing students regarding menstrual disorders through an educational training program. Int J Nurs Sci. 2017;7:35–43.

Natt AM, Khalid F, Sial SS. Relationship between examination stress and menstrual irregularities among medical students of Rawalpindi Medical University. J Rawalpindi Med Coll. 2018;22(S-1):44–7.

Ansong E, Arhin SK, Cai Y, Xu X, Wu X. Menstrual characteristics, disorders and associated risk factors among female international students in Zhejiang Province, China: a cross-sectional survey. BMC Womens Health. 2019;19(1):35.

Nagma S, Kapoor G, Bharti R, Batra A, Batra A, Aggarwal A, et al. To evaluate the effect of perceived stress on menstrual function. J Clin Diagn Res JCDR. 2015;9(3):QC01.

Maniam J, Antoniadis C, Morris MJ. Early-life stress, HPA axis adaptation, and mechanisms contributing to later health outcomes. Front Endocrinol. 2014;5:73.

Ding C, Wang J, Cao Y, Pan Y, Lu X, Wang W, et al. Heavy menstrual bleeding among women aged 18–50 years living in Beijing, China: prevalence, risk factors, and impact on daily life. BMC Womens Health. 2019;19(1):27.

Schliep KC, Zarek SM, Schisterman EF, Wactawski-Wende J, Trevisan M, Sjaarda LA, et al. Alcohol intake, reproductive hormones, and menstrual cycle function: a prospective cohort study. Am J Clin Nutr. 2015;102(4):933–42.

Erol A, Ho AMC, Winham SJ, Karpyak VM. Sex hormones in alcohol consumption: a systematic review of evidence. Addict Biol. 2019;24(2):157–69.

Shechter A, Boivin DB. Sleep, hormones, and circadian rhythms throughout the menstrual cycle in healthy women and women with premenstrual dysphoric disorder. Int J Endocrinol. 2010. https://doi.org/10.1155/2010/259345.

Hossam H, Fahmy N, Khidr N, Marzouk T. The relationship between menstrual cycle irregularity and body mass index among secondary schools pupils. IOSR J Nurs Health Sci. 2016;5(1):48–52.

Dutta BK, Saikia T, Prafulla M. Study of menstrual cycle disorders in adolescent girls in relation to BMI. J Evid Based Med Healthc. 2018;5(47):3239–44.

Ganesh R, Ilona L, Fadil R. Relationship between body mass index with menstrual cycle in senior high school students. Althea Med J. 2015;2(4):555–60.

Ganganahalli P, Kumbhar S, Mohite VR, Mohite R. Common menstrual problems among slum adolescent girls of western Maharashtra, India. J Krishna Inst Med Sci Univ. 2013;02:89–97.

Mohite R, Mohite V, Kumbhar S, Ganganahalli P. Common menstrual problems among slum adolescent girls of western Maharashtra, India. J Krishna Inst Med Sci (JKIMSU). 2013;2(1).

Sen LC, Annee IJ, Akter N, Fatha F, Mali SK, Debnath S. Study on relationship between obesity and menstrual disorders. Asian J Med Biol Res. 2018;4(3):259–66.

Gerasimova L, Denisov M, Samoilova A, Gunin A, Denisova T. Role of iodine deficiency in the development of menstrual disorders in young females. J Clin Med Therapeutics. 2016;8(4(eng)).

Leung A, Pearce EN, Braverman LE. Role of iodine in thyroid physiology. Expert Rev Endocrinol Metab. 2010;5(4):593–602.

Krassas G, Poppe K, Glinoer D. Thyroid function and human reproductive health. Endocr Rev. 2010;31(5):702–55.

Acknowledgements

The authors greatly appreciate the cooperation and support of all participants and are grateful to data collectors and supervisors.

Funding

Debre Berhan University.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Dr. Esubalew Tesfahun and Abay Brile designed the study and supervised the work in all phases. Enguday Demeke conducted the statistical analysis and drafts the manuscript. Abay Brile and Dr. Esubalew Tesfahun critically revised the manuscript. All authors read and approved the final version of the manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate

The ethical committee approved: the present study was approved by the ethics committee of Debre Berhan University in 2020. The objectives of the study were explained to the participants and their consent was obtained through a written informed consent document before soliciting information.

Consent for publication

Not applicable as this manuscript does not include details, images, or videos relating to individual participants.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/. The Creative Commons Public Domain Dedication waiver (http://creativecommons.org/publicdomain/zero/1.0/) applies to the data made available in this article, unless otherwise stated in a credit line to the data.

About this article

Cite this article

Zeru, A.B., Gebeyaw, E.D. & Ayele, E.T. Magnitude and associated factors of menstrual irregularity among undergraduate students of Debre Berhan University, Ethiopia. Reprod Health 18, 101 (2021). https://doi.org/10.1186/s12978-021-01156-1

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/s12978-021-01156-1