Abstract

Background

Pelvic organ prolapse remains the public health challenge globally. Existing evidences report the effect of woman’s weight on the pelvic organ prolapse inconsistently and this urges the need of pooled body weight effect on the pelvic organ prolapse. Although there was a previous work on this regard, it included papers reported before June 18/2015. Thus, updated and comprehensive evidence in this aspect is essential to devise strategies for interventions.

Objective

This review aimed at synthesizing evidence regarding the pooled effect of body weight on the pelvic organ prolapsed.

Methods

For this review, we searched all available articles through databases including PubMed, Web of Sciences, CINAHL, JBI library, Cochran library, PsycInfo and EMBASE as well as grey literature including Mednar, worldwide science, PschEXTRA and Google scholar. We included cohort, case–control, cross-sectional and experimental studies which had been reported between March 30, 2005 to March 30, 2020. In the effect analysis, we utilized random model. The heterogeneity of the studies was determined by I2 statistic and the publication bias was checked by Egger’s regression test. Searching was limited to studies reported in the English language.

Results

A total of 14 articles with 53,797 study participants were included in this systematic review (SR) and meta analysis (MA). The pooled result of this Meta analyses depict that body mass index (BMI) doesn’t have statistical significant association with pelvic organ prolapse.

Conclusion

This review point out that women’s body mass index has no significant effect on the development of pelvic organ prolapse. However, the readers should interpret the result with cautions due to the presence of considerable limitations in this work.

Trial registration The protocol of this systematic review (SR) and meta analysis (MA) has been registered in PROSPERO databases with the Registration number of CRD42020186951

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Pelvic organ prolapse (POP) is an anatomic support defect of the pelvic viscera. It may be resulted from a series of long term failure of supporting and suspension mechanisms of the uterus and the vaginal wall. The defect in the supporting structures results in downward displacement of structures that are normally located adjacent to the vaginal vault [1, 2].

Pelvic organ prolapsed (POP) severely affects women’s quality of life in several ways. Women with POP can feel different prolapse symptoms like “something coming down” and other urinary, bowel, and sexual symptoms [3,4,5]. It has socioeconomic and health consequences, affecting overall health and sexual function. It has been a major gynecologic problem in developed and developing nations [4, 6, 7].

Different risk factors such as increased maternal age and parity were identified to be linked to development of POP. However, most of those factors are non-modifiable. Similarly, maternal body mass index, which is a modifiable variable, also had been mentioned to be a determinant of POP although there are inconsistent reports across studies [8, 9].

As to the authors’ best knowledge, there is limited updated information on the pooled effect of maternal body mass index (BMI) on POP. In this regard, we obtained one systematic review (SR) and meta analyses (MA) regarding the effect of obesity on POP [10]. However, its search was limited on Pub Med/MEDLINE and included only papers published before June 18, 2015. We also found one related protocol which is limited to studies done in low and middle income countries. In addition, there is one review which is focused only on qualitative aspect in this aspect [11]

Thus, the current work was intended to fill these gaps. Accordingly, we included all the available published studies located in all accessible databases which had been reported between March 30/2005 to March 30/2020. By doing so, the current SR and MA come up with the evidences generated from existing studies. Thus, this review article was aimed at synthesizing the pooled effect of maternal BMI on pelvic organ prolapse globally.

Method

Protocol registration

The protocol of this SR and MA has been registered in the International Prospective Register of Systematic Reviews (PROSPERO) with the Registration number of CRD42020186951.

Reporting

The Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic reviews and meta-analysis (PRISMA) guideline was utilized to report the results of this SR and MA.

Databases and searching strategies

We searched through all available articles from PubMed using (((((("Women"[Mesh]) OR "Female"[Mesh]) AND ("Body Weight"[Mesh] OR "Weight Gain"[Mesh] OR "Body Weight Changes"[Mesh] OR "Weight Loss"[Mesh])) OR ("Obesity"[Mesh] OR "Obesity, Abdominal"[Mesh] OR "Obesity, Morbid"[Mesh] OR "Obesity, Maternal"[Mesh])) OR "Thinness"[Mesh]) AND "Pelvic Organ Prolapse"[Mesh]). We also tried to search using Web of Sciences, CINAHL, JBI library, Cochran library, PsycInfo and EMBASE databases though some of which are inaccessible. Similarly, we searched for grey literature through Mednar, worldwide science, PschEXTRA and Google scholar. In addition, we searched articles from the different institutional online research repositories and Reference lists of included studies using the following searching terms: “Body weight”, “Obesity”, “Pelvic organ prolapse”, “Body weight gain”, “POP”, “uterine prolapse”, “genital prolapse”, “enterocele”, “cystocele”, “anterior wall prolapse”,” rectocele” and “posterior wall prolapse” as a combination and as a single term.. We have conducted the search until March 30, 2020 and back to the previous recent 15 years.

Inclusion and exclusion criteria

Articles included met the following criteria: (1) observational studies including experimental, cohort, case–control and cross-sectional, (2) published and unpublished studies which had been reported between March 30/2005 to March 30/2020, (3) studies contained the OR, RR or HR of BMI with respect to POP, and (4) Studies on POP and BMI reported in English.

However, conference papers, editorials, trials, reviews, program evaluations, and only qualitative studies and all studies which had reported only the mean effect (OR, RR or HR) of BMI with respect to POP were excluded since such results may bring about difficulty in aggregated OR interpretation (as the aggregated OR is intended to be interpreted and compared with the reference group (i.e., normal BMI)).

Outcome measurement

The outcome variable for this protocol is POP (Yes, No). All forms of prolapses reported as POP, uterine prolapse, genital prolapse, enterocele, cystocele/anterior wall prolapse or rectocele/posterior wall prolapse were counted as an outcome. Moreover, we included prolapses which had been either subjectively self-reported symptomatic prolapse or objectively measured prolapses as indicated by ICD codes, as well as prolapse measured through pelvic exams by trained professionals for all severities of prolapse. For the ease of data aggregation, reports of Baden–Walker Halfway grading system of grade 1 or more, or Pelvic Organ Prolapse Quantification (POP-Q) system stage I or more were considered comparable.

Study selection and quality assessment

Primarily, all retrieved studies have been imported to Endnote version 7 citation managers. Consequently, duplicated studies were carefully removed from Endnote. Then, two independent authors screened and assessed the titles and abstracts and review the full texts. Any disagreement had been solved through discussion and communication with the primary authors of the studies. After the full text review, two investigators assessed the quality of the studies independently using the Joanna Brigg’s Institute (JBI) quality appraisal criteria adapted for respective study. Accordingly, studies with low risk i.e. whenever fitted to 50% and/or above quality assessment checklist criteria were included in this SR and MA.

Data extraction

We extracted the first author of the study, year of publication, study area, design, study population, outcome variable measure, sample size, OR of BMI 30+, OR of BMI < 18.5 and OR of BMI (25.5–29.9).

We have focused on extracting of AOR as much as possible because of its importance for having adjusted and/or controlled possible confounders. For studies with no AOR, we have also searched for COR.

Data analysis

A Stata version 11 statistical software was used for all statistical analysis. We used a random model for MA to estimate the pooled OR of BMI30+, OR of BMI < 18.5 and OR of BMI 25.5–29.9. We assessed the percentages of total variations across studies using I2 statistics. The values of I2, 25, 50, and 75% was represented low, moderate, and high heterogeneity respectively. Publication bias across studies was checked using Egger’s regression test.

Results

Findings and selection process

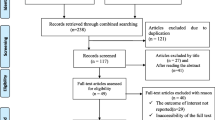

We obtained a total of 21,319 papers from all searching strategies. From these, we found about 5241 literature while we limit a searching filter date from March 30/2005 till March 30/2020. Upon filtration for duplication (n = 343), we selected 4898 articles. Thereafter, irrelevant studies (n = 4832) were removed based on the review of titles and abstracts. Among 43 articles which passed for further full-text review, about 29 articles were excluded for different reasons [3, 7,8,9, 12,13,14,15,16,17,18,19,20,21,22,23,24,25,26,27,28,29,30,31,32,33,34,35,36]. Finally, 14 articles were found relevant to assess the effect of BMI on POP (Fig. 1).

Characteristics of the included studies

About 14 studies with 53,797 study participants were included in this SR and MA. Regarding the study area of the articles; two studies in Ethiopia [37, 38], one study in Tanzania [39],one study in United Arab Emirates [40], four studies in USA [41,42,43,44], three studies in Sweden [14, 45, 46], one study in UK [47], one study in New Zeeland [48], and one study in Nepal [49] were included. As far as the study design of the included articles concerned, we included seven studies case control [37,38,39, 43, 45, 46, 49], three cohort [14, 47, 48], two cross sectional [40, 44] and two RCT [41, 42] studies. Concerning the POP measurement in the included articles, seven studies measured POP objectively [37, 39, 41,42,43, 48, 49] and the remaining seven measured subjectively [14, 38, 40, 44,45,46,47] (Table 1).

The effect of BMI on POP

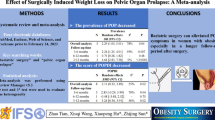

Two studies reported the statistical significant association between BMI < 18.5 kg/m2 and POP [37, 38]. Likewise, five studies [41,42,43, 45, 48] reported that BMI of 25–29.9 kg/m2 had significant association with POP. Similarly, five studies [14, 41,42,43, 48] presented the finding exhibiting the significant association between BMI ≥ 30 kg/m2 and POP. In the MA, however, no statistical significant association is observed between each category of BMI and POP for all included articles. Similarly, the MA results depict that the pooled (overall) effect of each category of BMI on POP is statistically insignificant (Figs. 2, 3 and 4).

Discussion

This SR and MA aimed at synthesizing the pooled effect of BMI on POP occurrences. The pooled MA results indicate that BMI index has no significant association with POP. This contradicts the result of previous similar work [10]. The previous SR and MA work was included papers published June 18, 2015. On the other hand, the current work included articles published between March 30/2005 and March 30/2020. Therefore, one possible justification for the discrepancy on the effect of BMI on POP could be publication time difference across included papers. In this regard, the former study is differed from the current study on two perspectives. First, the former study had included all eligible studies published from June 18/2015 backward unlike the current study which has not included articles published March 30/2005 back. Second, the previous MA and SR study had not considered the recent studies published since June 19/2015 onwards in contrast to the current study which included papers published till March 30/2020. Over time trend, the life styles of people are continually changing, and BMI is tremendously sensitive to changes in life styles.

The findings of this study should be interpreted with cautions as the study has a number of limitations. First of all, there is a high heterogeneity in definition of POP and categories of BMI across included studies. In this aspect, certain studies had measured POP subjectively (symptomatic based) [38, 45, 46] while others reported objectively [37, 48, 49]. There were also variations in cut-off points in POP definitions even within studies reported objectively ranged from stage ≥ 1[49] to stage ≥ 3 [37]. Second, some studies reported BMI’s category exhaustively (< 18.5 kg/m2, 18.5–25.5 kg/m2, 25.5–29.9 kg/m2 and ≥ 30 kg/m2) while others reported it in a simple way (< 18.5 kg/m2, 18.5–25.5 kg/m2 and ≥ 25 kg/m2). Even other else reported a single figure of the mean value of BMI. Third, some of the studies presented only its crude odds ratio unlike the rests which had included the adjusted odds ratio too. Lastly, there was a quite disparity in study participants across included studies (Fig. 3). Therefore, a non- significant association between BMI and POP in the pooled result could be attributed to the aforesaid shortcomings of this study.

Conclusion

In this SR and MA, BMI has no pooled significant association with POP. However, the readers should interpret the result with cautions due to the presence of considerable limitations in this work.

Limitations

As the categories of BMI had been reported inconsistently across literature, we forced to report the findings of these variables with some sort of variation in categories aggregately. In addition, this SR and MA might miss important related articles as some important studies had reported the findings in different way which made the data extraction difficult and the data interpretation hard.

Availability of data and materials

The datasets employed in the current study can be available from the corresponding author upon the reasonable request.

Abbreviations

- AOR:

-

Adjusted odds ratio

- BMI:

-

Body mass index

- COR:

-

Crude odds ratio

- MA:

-

Meta analyses

- POP:

-

Pelvic organ prolapse

- PROSPERO:

-

Prospective Register of Systematic Reviews

- SR:

-

Systematic reviews

- UNFPA:

-

United Nation

References

Hallock JL, Handa VL. The epidemiology of pelvic floor disorders and childbirth: an update. Obstet GynecolClin N Am. 2016;43(1):1–13.

Merrell J, Brethauer S, Windover A, Ashton K, Heinberg L. Psychosocial correlates of pelvic floor disorders in women seeking bariatric surgery. SurgObesRelat Dis. 2012;8(6):792–6.

Myers DL, Sung VW, Richter HE, Creasman J, Subak LL. Prolapse symptoms in overweight and obese women before and after weight loss. Female Pelvic Med ReconstrSurg. 2012;18(1):55–9.

Ramalingam K, Monga A. Obesity and pelvic floor dysfunction. Best Pract Res Clin Obstet Gynaecol. 2015;29(4):541–7.

What to do about pelvic organ prolapse. Many women are living with this uncomfortable condition. Here are your next steps if you're one of them. Harvard women's health watch. 2014;21(10):4.

Bilgic D, Gokyildiz S, KizilkayaBeji N, Yalcin O, Gungor UF. Quality of life and sexual function in obese women with pelvic floor dysfunction. Women Health. 2019;59(1):101–13.

Rodríguez-Mias NL, Martínez-Franco E, Aguado J, Sánchez E, Amat-Tardiu L. Pelvic organ prolapse and stress urinary incontinence, do they share the same risk factors? Eur J Obstet GynecolReprod Biol. 2015;190:52–7.

Washington BB, Erekson EA, Kassis NC, Myers DL. The association between obesity and stage II or greater prolapse. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2010;202(5):503.e1-4.

Awwad J, Sayegh R, Yeretzian J, Deeb ME. Prevalence, risk factors, and predictors of pelvic organ prolapse: a community-based study. Menopause (New York, NY). 2012;19(11):1235–41.

Giri A, Hartmann KE, Hellwege JN, Velez Edwards DR, Edwards TL. Obesity and pelvic organ prolapse: a systematic review and meta-analysis of observational studies. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2017;217(1):11-26.e3.

Thubert T, Deffieux X, Letouzey V, Hermieu JF. Obesity and urogynecology: a systematic review. Progres en urologie: journal de l’Associationfrancaised’urologieet de la Societefrancaised’urologie. 2012;22(8):445–53.

Akmel M, Segni H. Pelvic organ prolapse in Jimma University specialized hospital, southwest ethiopia. Ethiop J Health Sci. 2012;22(2):85–92.

Bodner-Adler B, Kimberger O, Laml T, Halpern K, Beitl C, Umek W, et al. Prevalence and risk factors for pelvic floor disorders during early and late pregnancy in a cohort of Austrian women. Arch Gynecol Obstet. 2019;300(5):1325–30.

Bohlin KS, Ankardal M, Nüssler E, Lindkvist H, Milsom I. Factors influencing the outcome of surgery for pelvic organ prolapse. Int Urogynecol J. 2018;29(1):81–9.

Chen HY, Chung YW, Lin WY, Wang JC, Tsai FJ, Tsai CH. Collagen type 3 alpha 1 polymorphism and risk of pelvic organ prolapse. Int J Gynaecol Obstet. 2008;103(1):55–8.

Chung SH, Kim WB. Various approaches and treatments for pelvic organ prolapse in women. J Menopausal Med. 2018;24(3):155–62.

Eleje G, Udegbunam O, Ofojebe C, Adichie C. Determinants and management outcomes of pelvic organ prolapse in a low resource setting. Ann Med Health Sci Res. 2014;4(5):796–801.

Gray T, Money-Taylor J, Li W, Farkas AG, Campbell PC, Radley SC. What is the effect of body mass index on subjective outcome following vaginal hysterectomy for prolapse? Int Neurourol J. 2019;23(2):136–43.

Li Z, Xu T, Li Z, Gong J, Liu Q, Wang Y, et al. An epidemiologic study on symptomatic pelvic organ prolapse in obese Chinese women: a population-based study in China. Diabetes MetabSyndrObes Targets Ther. 2018;11:761–6.

Milsom I, Gyhagen M. Breaking news in the prediction of pelvic floor disorders. Best Pract Res Clin Obstet Gynaecol. 2019;54:41–8.

Nakad B, Fares F, Azzam N, Feiner B, Zilberlicht A, Abramov Y. Estrogen receptor and laminin genetic polymorphism among women with pelvic organ prolapse. Taiwan J Obstet Gynecol. 2017;56(6):750–4.

Quiroz LH, Muñoz A, Shippey SH, Gutman RE, Handa VL. Vaginal parity and pelvic organ prolapse. J Reprod Med. 2010;55(3–4):93–8.

Shalom DF, Lin SN, St Louis S, Winkler HA. Effect of age, body mass index, and parity on Pelvic Organ Prolapse Quantification system measurements in women with symptomatic pelvic organ prolapse. J Obstet Gynaecol Res. 2012;38(2):415–9.

Smith FJ, Holman CD, Moorin RE, Tsokos N. Lifetime risk of undergoing surgery for pelvic organ prolapse. Obstet Gynecol. 2010;116(5):1096–100.

Swift SE, Pound T, Dias JK. Case-control study of etiologic factors in the development of severe pelvic organ prolapse. Int Urogynecol J Pelvic Floor Dysfunct. 2001;12(3):187–92.

Thapa S, Angdembe M, Chauhan D, Joshi R. Determinants of pelvic organ prolapse among the women of the western part of Nepal: a case-control study. J Obstet Gynaecol Res. 2014;40(2):515–20.

Wusu-Ansah OK, Opare-Addo HS. Pelvic organ prolapse in rural Ghana. Int J Gynaecol Obstet. 2008;103(2):121–4.

Braekken IH, Majida M, EllströmEngh M, Holme IM, Bø K. Pelvic floor function is independently associated with pelvic organ prolapse. BJOG Int J Obstet Gynaecol. 2009;116(13):1706–14.

Chen Y, Johnson B, Li F, King WC, Connell KA, Guess MK. The effect of body mass index on pelvic floor support 1 year postpartum. Reprod Sci (Thousand Oaks, Calif). 2016;23(2):234–8.

Diez-Itza I, Arrue M, Ibañez L, Paredes J, Murgiondo A, Sarasqueta C. Influence of mode of delivery on pelvic organ support 6 months postpartum. Gynecol Obstet Invest. 2011;72(2):123–9.

Forsman M, Iliadou A, Magnusson P, Falconer C, Altman D. Diabetes and obesity-related risks for pelvic reconstructive surgery in a cohort of Swedish twins. Diabetes Care. 2008;31(10):1997–9.

Fritel X, Varnoux N, Zins M, Breart G, Ringa V. Symptomatic pelvic organ prolapse at midlife, quality of life, and risk factors. Obstet Gynecol. 2009;113(3):609–16.

Gyhagen M, Bullarbo M, Nielsen TF, Milsom I. Prevalence and risk factors for pelvic organ prolapse 20 years after childbirth: a national cohort study in singleton primiparae after vaginal or caesarean delivery. BJOG Int J Obstet Gynaecol. 2013;120(2):152–60.

Isık H, Aynıoglu O, Sahbaz A, Selimoglu R, Timur H, Harma M. Are hypertension and diabetes mellitus risk factors for pelvic organ prolapse? Eur J Obstet GynecolReprod Biol. 2016;197:59–62.

Rodrigues AM, Girão MJ, da Silva ID, Sartori MG, Martins Kde F, Castro RA. COL1A1Sp1-binding site polymorphism as a risk factor for genital prolapse. Int Urogynecol J Pelvic Floor Dysfunct. 2008;19(11):1471–5.

Slieker-ten Hove MC, Pool-Goudzwaard AL, Eijkemans MJ, Steegers-Theunissen RP, Burger CW, Vierhout ME. Symptomatic pelvic organ prolapse and possible risk factors in a general population. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2009;200(2):184.e1-7.

Asresie A, Admassu E, Setegn T. Determinants of pelvic organ prolapse among gynecologic patients in Bahir Dar, North West Ethiopia: a case–control study. Int J Women’s Health. 2016;8:713–9.

Henok A. Prevalence and factors associated with pelvic organ prolapse among pedestrian back-loading women in bench Maji Zone. Ethiop J Health Sci. 2017;27(3):263–72.

Masenga GG, Shayo BC, Rasch V. Prevalence and risk factors for pelvic organ prolapse in Kilimanjaro, Tanzania: a population based study in Tanzanian rural community. PLoS ONE. 2018;13(4):e0195910.

Elbiss HM, Osman N, Hammad FT. Prevalence, risk factors and severity of symptoms of pelvic organ prolapse among Emirati women. BMC Urol. 2015;15:66.

Kudish BI, Iglesia CB, Sokol RJ, Cochrane B, Richter HE, Larson J, et al. Effect of weight change on natural history of pelvic organ prolapse. Obstet Gynecol. 2009;113(1):81–8.

Kudish BI, Iglesia CB, Gutman RE, Sokol AI, Rodgers AK, Gass M, et al. Risk factors for prolapse development in white, black, and Hispanic women. Female Pelvic Med ReconstrSurg. 2011;17(2):80–90.

Whitcomb EL, Rortveit G, Brown JS, Creasman JM, Thom DH, Van Den Eeden SK, et al. Racial differences in pelvic organ prolapse. Obstet Gynecol. 2009;114(6):1271–7.

Rortveit G, Brown JS, Thom DH, Van Den Eeden SK, Creasman JM, Subak LL. Symptomatic pelvic organ prolapse: prevalence and risk factors in a population-based, racially diverse cohort. Obstet Gynecol. 2007;109(6):1396–403.

Miedel A, Tegerstedt G, Maehle-Schmidt M, Nyrén O, Hammarström M. Nonobstetric risk factors for symptomatic pelvic organ prolapse. Obstet Gynecol. 2009;113(5):1089–97.

Tegerstedt G, Miedel A, Maehle-Schmidt M, Nyrén O, Hammarström M. Obstetric risk factors for symptomatic prolapse: a population-based approach. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2006;194(1):75–81.

Dolan LM, Hilton P. Obstetric risk factors and pelvic floor dysfunction 20 years after first delivery. Int Urogynecol J. 2010;21(5):535–44.

Glazener C, Elders A, MacArthur C, Lancashire RJ, Herbison P, Hagen S, et al. Childbirth and prolapse: long-term associations with the symptoms and objective measurement of pelvic organ prolapse. BJOG Int J Obstet Gynaecol. 2013;120(2):161–8.

Devkota HR, Sijali TR, Harris C, Ghimire DJ, Prata N, Bates MN. Bio-mechanical risk factors for uterine prolapse among women living in the hills of west Nepal: a case-control study. Womens Health. 2020;16:1745506519895175.

Acknowledgements

We would like to forward our deepest appreciation to UNFPA for grant support. All authors contributed equally to this research.

Funding

The research was supported by a Grant from UNFPA. The granting agency did not have a role in the design; Collection, analysis, and interpretation of data or; in writing the manuscript.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

CBZ, WFC and MSM: have contributed to the conception and design, acquisition of the data, analysis and interpretation of data, drafting the manuscript, critical revision of the manuscript, revised the subsequent of drafts of manuscript. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

ABA & TMA: have contributed to analysis and interpretation of data, critical revision of the manuscript, revised the subsequent of drafts of manuscript, final approval of the version to be published. All authors read and approved the final version of the manuscript to be submitted for publication.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate

Not applicable.

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Competing interests

The authors declare that there is no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/. The Creative Commons Public Domain Dedication waiver (http://creativecommons.org/publicdomain/zero/1.0/) applies to the data made available in this article, unless otherwise stated in a credit line to the data.

About this article

Cite this article

Zenebe, C.B., Chanie, W.F., Aregawi, A.B. et al. The effect of women’s body mass index on pelvic organ prolapse: a systematic review and meta analysis. Reprod Health 18, 45 (2021). https://doi.org/10.1186/s12978-021-01104-z

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/s12978-021-01104-z