Abstract

Objectives

To characterize maternal Zika virus (ZIKV) infection and complement the evidence base for the WHO interim guidance on pregnancy management in the context of ZIKV infection.

Methods

We searched the relevant database from inception until March 2016. Two review authors independently screened and assessed full texts of eligible reports and extracted data from relevant studies. The quality of studies was assessed using the Newcastle-Ottawa Scale (NOS) and the National Institute of Health (NIH) tool for observational studies and case series/reports, respectively.

Results

Among 142 eligible full-text articles, 18 met the inclusion criteria (13 case series/reports and five cohort studies). Common symptoms among pregnant women with suspected/confirmed ZIKV infection were fever, rash, and arthralgia. One case of Guillain-Barré syndrome was reported among ZIKV-infected mothers, no other case of severe maternal morbidity or mortality reported. Complications reported in association with maternal ZIKV infection included a broad range of fetal and newborn neurological and ocular abnormalities; fetal growth restriction, stillbirth, and perinatal death. Microcephaly was the primary neurological complication reported in eight studies, with an incidence of about 1% among newborns of ZIKV infected women in one study.

Conclusion

Given the extensive and variable fetal and newborn presentations/complications associated with prenatal ZIKV infection, and the dearth of information provided, knowledge gaps are evident. Further research and comprehensive reporting may provide a better understanding of ZIKV infection in pregnancy and attendant maternal/fetal complications. This knowledge could inform the creation of effective and evidence-based strategies, guidelines and recommendations aimed at the management of maternal ZIKV infection. Adherence to current best practice guidelines for prenatal care among health providers is encouraged, in the context of maternal ZIKV infection.

Similar content being viewed by others

Plain english summary

Aedes mosquitoes transmit Zika virus (ZIKV) infection, its clinical presentation in humans is often mild or asymptomatic. Due to a marked increase in the number of symptomatic or suspected cases across continents, ZIKV infection was declared a Public Health Emergency of International Concern (PHEIC) on February 1, 2016. Pregnant women are at an exceptional risk of being affected with potential adverse effects. To describe maternal Zika virus (ZIKV) infection and complement the evidence base for the WHO interim guidance on pregnancy management and in the context of ZIKV infection, we did a systematic review.

We conducted database searches, independent screening of records and assessment of resulting full texts from which we extracted data. We further assessed the quality of the included studies.

Of the 142 eligible full-text articles, we extracted data from the 18 studies which met the inclusion criteria (13 case series/reports and five cohort studies). Among the pregnant women with suspected/confirmed ZIKV infection in these studies, fever, rash and joint-pain were the commonly reported symptoms. Neurological affectation (Guillain-Barre syndrome) was reported in one mother, no other cases of severe maternal illness or deaths were reported. Complications reported in association with maternal ZIKV infection included a broad range of fetal and newborn neurological and ocular abnormalities; fetal growth restriction, stillbirth, and perinatal death. Microcephaly was the primary neurological complication reported in eight studies, with an incidence of about 1% in one study.

In conclusion, knowledge gaps on the features characterising maternal ZIKV infection and its effects are evident. Further research and better reporting practices may help create effective strategies aimed at the management of maternal ZIKV infection and subsequent fetal complications. Pregnant women and health providers are encouraged to adhere to current best practice guidelines, in the context of maternal ZIKV infection.

Background

Since the late 1940s, there have been reports of Zika virus (ZIKV) isolated from rhesus monkeys in Uganda, and human cases in Tanzania and Nigeria [1, 2]. At present, ZIKV has a broad distribution across sub-Saharan Africa, South-East Asia, and the Americas [3]. ZIKV belongs to the Flaviviridae family of viruses and is transmitted by Aedes mosquitoes.

In humans, ZIKV infection is often mild or asymptomatic. However, an exponential increase in the number of symptomatic or suspected cases across continents has intensified international concern [4]. Prior to 2007, few cases of ZIKV infection were reported [5]. Thereafter, an infectious outbreak affecting 74.6% of the Micronesian Yap population [6] and 32,000 people in the French Polynesian region in 2013–2014 were reported [7, 8]. In the latest outbreak in 2015, up to 1.3 million suspected cases were identified in Brazil over a 9-month period [9, 10]. In addition to transmission by Aedes mosquitoes, sexual transmission has also been reported [11, 12].

Despite the international efforts to curb its spread, ZIKV infection has expanded to 62 countries and territories, and is projected to increase due to potential climate change affecting the spread of the ZIKV Aedes vector [7, 13,14,15,15]. Notably in 2015, a 20-fold increase in the incidence of microcephaly relative to previous years was reported with the onset of ZIKV transmission in northeastern Brazil. This trend led to the World Health Organization (WHO) declaring a Public Health Emergency of International Concern (PHEIC) on February 1, 2016 [13, 16, 17].

Pregnant women are at exceptional risk of being infected with ZIKV infection and exhibiting potential adverse effects, including a wide range of congenital abnormalities associated with ZIKV infection in utero. Delayed or arrested neurological development and complications common in fetuses and neonates born to ZIKV-infected women, may drain family resources due to the need for special care. Perinatal deaths may further impose an emotional burden on affected families. The health systems in most ZIKV-affected areas have limited resources to manage the current outbreak and its consequences.

Many gaps in the knowledge regarding ZIKV infection exist, these include, the clinical spectrum of disease presentation in infected pregnant women, mechanisms of vertical transmission, and the risk of complications in mother, fetus and newborn. Also, the impact of ZIKV co-infection with other flaviviruses on pregnancy as well as the long-term consequence of ZIKV infection among infants and adults of reproductive age is unclear. As part of the process to complement the evidence base for WHO interim guidance on pregnancy care in the context of ZIKV infection and close the knowledge gaps, we conducted a systematic review.

Methods

Search strategy

We searched the following electronic databases: MEDLINE, EMBASE, CINAHL, World Health Organization Global Health Library (WHOGL), and Cochrane Central Register of Controlled Trials (CENTRAL) on March 3, 2016. An information specialist configured search terms for each database according to the level of term indexation. Search terms included flavivirus, chikungunya virus, fever, arbovirus, Zika, congenital malformations, cephalometry, and nervous system abnormalities as shown in Additional file 1). There were no dates, language or study design restrictions. We registered this review in PROSPERO, the international prospective register of systematic reviews of the University of York and the National Institute for Health Research, under the number CRD4201603969.

Selection of studies

We considered all study designs including randomized controlled trials, prospective or retrospective cohorts, cross-sectional, case-control studies and case series/reports. Original reports, briefs, letters, editorials, correspondence and news reports were considered for inclusion. A minimum of two review authors assessed the title and abstract of references for relevance to review objectives. We evaluated the full text of potentially eligible records for inclusion relative to our review objectives. The review objectives included primary data on disease characteristics in ZIKV-infected pregnant women and their babies and the risk of adverse pregnancy outcomes. References of included reports were also searched for potentially eligible studies. Disagreements on the eligibility of reports, where present, were resolved by consensus with a third review author.

Types of studies

We included all studies reporting on ZIKV infection and complications in pregnant women residing in or with a history of travel to areas of ongoing ZIKV transmission or recent ZIKV outbreaks. Studies comparing pregnant and non-pregnant women with ZIKV infection were considered for inclusion where available. We excluded any study or report on non-pregnant populations or lacking primary data.

Types of participants

Pregnant women suspected of being at risk of, or diagnosed with ZIKV infection regardless of their location, or who have had sexual contact with a partner who (i) recently returned from an area of active ZIKV transmission, or (ii) was diagnosed with ZIKV infection.

Data extraction and synthesis

Two review authors independently extracted and presented data based on the review objectives in an agreed data collection form. We summarized the data in a descriptive form (Table 1).

We extracted information on study design, sample size, history of maternal and fetal ZIKV infection, symptoms, presence and type of clinical features, pregnancy-specific complications during pregnancy, childbirth or postpartum period. The absolute risk of microcephaly and other birth defects was also recorded where available.

Risk of bias assessment

Two review authors conducted independent assessments on the quality of included studies. Where discordance in ranking was observed, this was resolved by consensus or discussion with a third review author. For individual case series/reports, a quality assessment of the National Institute of Health Tool (NIH) [18] was applied. This tool includes questions based on nine criteria to which either of the binary answers (Yes/No) was allotted. Based on the number of ‘Yes’ answers, a rating of good (7 – 9), fair (4 – 6) or poor (≤3) was allocated to the individual study and differences in quality ratings amended by consensus. Studies for which the criteria were irrelevant were labelled ‘not applicable’ and ‘cannot determine’ if such information was lacking in the study.

For observational studies, we applied the Newcastle-Ottawa Scale [18] which consisted of lead questions aimed at assessing three domains – selection, comparability, and outcome. For each outcome, a maximum of three points could be allotted as previously described [20].

Results

Search results

Search strategies identified 2316 records as shown in the PRISMA flow chart in Fig. 1. Based on the title and abstract screening, 2174 records were excluded due to lack of primary data and/or irrelevance to review objective. Of the resulting 142 eligible full texts, 18 studies met our inclusion criteria (reasons for exclusion are outlined in Additional file 2).

Characteristics of included studies

All but one study were published in 2016 [21]. The studies were conducted largely in South America: Brazil [11], Colombia [1], Puerto Rico [1], and Venezuela [1]. Other studies were conducted in France [1], Slovenia [1] and the USA [2]. In all studies, pregnant women were either living in areas of ongoing transmission [21–35], had resided in [36], or travelled [37] to ZIKV-affected areas during pregnancy.

Regarding study design, there were 13 case series/reports [21, 23–27, 28, 30, 32, 34–35] and five observational studies [22, 26, 29, 31, 33]. The observational studies were either prospective [33], retrospective [22] or mixed [29, 31] in design. All presented information on clinical manifestations, pregnancy-specific complications and diagnoses in women and their fetuses/newborns.

Diagnostic tests to confirm the presence of ZIKV infection in pregnant women included reverse transcription polymerase chain reaction (RT-PCR) for ZIKV nucleic material [21, 25, 29, 30, 33, 35, 37] and tests on serum [21, 24], breastmilk [21], amniotic fluid [37] and urine [24] samples. IgG and IgM antibody tests for viral ZIKV exposure were also conducted [24, 28, 33, 35]. Eleven of the 18 included studies conducted serological tests to exclude other infections such as dengue [21, 27, 32, 33], chikungunya [32], toxoplasmosis [22, 24, 27, 28, 32, 34], rubella [22–24, 27, 28, 32, 33], cytomegalovirus [22–24, 27, 28, 32, 33], herpes simplex virus [22, 24, 27, 28, 32], HIV [22, 24, 27, 28, 32, 35], Human T-cell lymphotrophic virus [35], Hepatitis C Virus [35] and Hepatitis B Virus [24].

For fetal imaging, ultrasound [26,24,, 30, 32, 35], computed tomography scanning for brain calcifications [25] and magnetic resonance imaging [37] were employed.

In some studies, ocular examinations were also conducted for the mother [34] and newborn [22, 34].

Characteristics of maternal ZIKV infection

Symptoms/signs/complications

No study suggested a higher risk of acquiring ZIKV infection in pregnant women compared to the non-pregnant population, after exposure to Aedes mosquitoes. Most studies only presented fetal and newborn features without further information on how these varied with the gestational age at the time of maternal ZIKV infection.

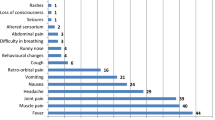

Rash was the most common sign of ZIKV infection in pregnant women in 15 of 18 included reports [21–29, 32–34]. Two of the remaining three studies (one observational study, one case series) did not report clinical manifestations during pregnancy as they focused on the newborns of ZIKV-infected mothers [30, 31]. Rash was absent in the third study as the mothers were asymptomatic [35]. In seven reports, the rash was further qualified as ‘a pruritic cutaneous rash with itching in the back and hands’, ‘generalised, descending macular’ or ‘generalised maculopapular’ [21, 28, 33], ‘petechial’ or ‘generalised’ [21, 28, 32, 33, 36]. Only one case-series reported on symptom occurrence after delivery in two ZIKV-infected pregnant women [21]. A 4-day duration of persistent rash in one pregnant woman and a pruritic rash on the third day after childbirth in the second case was observed. In the former, the rash started 2 days before and ended 2 days after delivery of a healthy infant. In the latter case, a mild fever and myalgia were also reported.

Other reported signs and symptoms included fever [22–24, 27–29, 32, 33], chills [23, 24], malaise [24, 29, 34], arthralgia [22, 24, 28, 29, 33, 34], myalgia [23, 24, 29, 32, 33], myotonia [23], asthenia [24], jaundice [24], paraesthesia [33], hemiparesis [24], headache [22, 28], conjunctivitis or conjunctival injections [23, 33], lymphadenopathy [33], pain (eye, abdominal, lumbar, pelvis, body and joint) [24, 29], anaemia [24], edema in lower limbs [24], nausea [25, 33], vomiting [33], dermal bleeding [33] and ‘respiratory findings’ [33].

The grade of fever was provided in three reports, a low grade fever of 37.5 to 38.0 °C in two reports [21, 33] and a “high fever” [36] in the third. Fever was absent in ZIKV-infected pregnant women in two case reports [35].

An observational study reported a significantly higher frequency of lymphadenopathy and conjunctival injections in ZIKV-infected compared with uninfected pregnant women [33].

Twelve studies provided information on trimester-specific occurrence of symptoms [21, 23, 24, 26–29, 32, 34]. Symptoms were observed more commonly in the first trimester [24,29,, 26–28, 32, 34]. Among the ZIKV-infected pregnant women in individual reports, seven studies reported no signs or symptoms [22, 24, 26, 28, 34, 35].

Neurological complications were reported in ZIKV-infected pregnant women in one case report [23] and one observational study [33]. Guillain-Barré syndrome (GBS) at 28 weeks gestation in addition to other typical ZIKV signs and symptoms were reported in one case report only [23]. The patient had respiratory distress that prompted intensive care unit (ICU) admission. She fully recovered within 3 weeks and gave birth to a normal infant at 39 weeks of gestation.

Preterm birth necessitating emergency caesarean delivery was reported in two observational studies [27, 33] and one case series [21]. In the two observational studies, intrauterine growth restriction (IUGR) was an underlying complication. In one of the studies [33], the two preterm births reported were due to IUGR accompanied by oligohydramnios, macular hypoplasia, and placental insufficiency in one fetus and anhydramnios in the other.

Miscarriages were reported in five ZIKV-infected pregnant women in two case series [27] and one observational study [33]. Stillbirths were also recorded in three pregnant women in one observational study and one case report [33, 35].

Characteristics of fetuses/newborns of ZIKV infected pregnant women

Fetuses

Complications

A wide spectrum of complications was reported in association with maternal ZIKV infection (Table 2). Microcephaly visible on fetal ultrasound was the main neurologic complication in two observational studies and six case series/reports [24, 27, 29, 30, 32, 33, 35]. Among them, ocular abnormalities [22, 28, 30, 32, 34], cerebral calcifications and cerebellar abnormalities were commonly reported [24, 30, 32–35]. In one observational study of 35 infants with microcephaly [26], 11 fetuses had intra-uterine brain injury accompanied by stunting of cerebral growth prior to birth. Cerebral abnormalities included brain atrophy, absent corpus callosum, and ventriculomegaly.

Ocular abnormalities included intraocular calcifications and microphthalmia [30, 32].

In fetuses of ZIKV-infected pregnant women, placental and umbilical [32, 33] and amniotic fluid [33] abnormalities were reported.

IUGR was reported in five studies (two observational, three case-series/reports) [21, 33] and stillbirths in two studies [33, 35]. Despite normal fetal biometrics at 14 weeks in one case of an asymptomatic ZIKV-infected pregnant woman, IUGR was detected at 18 weeks and accompanied by other neurological abnormalities including microcephaly, hydranencephaly, hydrops fetalis and eventual stillbirth [35].

Fetal deaths were reported in two studies (one case series and one observational study), these deaths occurred in four fetuses at > 30 weeks gestation [27, 33]. Elective terminations of pregnancies were conducted for seven pregnant women. However, the gestational age or trimester of termination was unknown [31].

Newborns

Symptoms/signs

Rash described as ‘transient isolated diffuse’ was reported in an infant on the fourth day post-delivery [21]. Other symptoms reported included conjunctivitis or conjunctival injections [24, 28].

Complications

Similar to fetuses, microcephaly was observed at birth in 11 studies (four observreports)/reports) [22, 26–30, 32–34] with accompanying ocular and brain abnormalities. In four studies, microcephaly that was observed at birth was preceded by a fetal diagnosis of IUGR [25, 32, 34, 35]. Ocular abnormalities included focal pigment mottling, chorioretinal macular atrophy, optic nerve abnormalities, cataracts, intra-ocular calcifications, microphthalmia, conjunctival injections, optic disc cupping, lens subluxation in addition to bilateral iris coloboma, foveal reflex loss, macular hypoplasia and scarring [22, 28, 34, 38].

Musculoskeletal abnormalities reported included clubfoot [33] and severe arthrogryposis [30, 32] in two case series. In one case report, ‘arthrogryposis’ was also reported at post-mortem examination [35].

Four studies reported the birth of healthy infants [23, 33, 37] and one study reported early neonatal deaths in three infants with microcephaly within 20 h of delivery [27].

Absolute risk of fetal microcephaly (and other birth defects) in women with ZIKV infection

No report provided detailed information from which factors related to ZIKV infection could be described. One observational study provided a trimester-specific modelling estimate risk for microcephaly in first [95 cases (95% confidence interval (CI) 34-191)], second [84 cases (95% CI 12–196)] and third [0 case (95% CI 0–251)] trimesters, per 10,000 ZIKV-infected pregnant women [30]. The baseline prevalence for the risk of microcephaly were 2% (0 – 8), corresponding to a risk ratio of 53.4 (95% CI 6.5 – 1061.2) in the first trimester; 4% (95% CI 0 – 12), corresponding to a risk ratio of 23.2 (95% CI 1.4 – 407.8) in the second trimester; and 10% (95% CI 3 – 18), corresponding to a risk ratio of 0 (95% CI 0 – 49.3) in the third trimester.

Fetal abnormalities, including microcephaly, were detected in women who underwent an ultrasound at time-points ranging between 26 and 30 weeks [30, 35, 36].

Impact of ZIKV co-infection in pregnancy

There was a lack of information on co-infection with other flaviviruses and common congenital infections in some studies. Serological tests were conducted in studies to exclude possible co-infections and/or antibody tests for previous exposure to other related flaviviruses.

Eleven reports assessed for the presence of co-infections, toxoplasmosis [22, 24, 27, 28, 32–35, 38], dengue [21, 27, 32], chikungunya [27, 32], HIV [22, 24, 27, 28, 32, 33, 35, 38], hepatitis B virus (HBV) [24], hepatitis C virus (HCV) [35], cytomegalovirus (CMV) [22, 24, 27, 28, 32, 33, 35, 38], herpes simplex virus (HSV) [22, 24, 27, 28, 32, 38], Epstein-Barr virus (EBV) [24], rubella [22, 24, 27, 28, 32, 33, 35, 38], human T lymphotrophic virus (HTLV) [35], parvovirus B19 [32], syphilis [24, 28, 32] and rheumatoid fever [24].

Four reports assessed previous exposure to other infections based on the presence of IgG [24, 28, 33, 35] and IgM [28, 35] antibody positivity to cytomegalovirus, rubella and toxoplasmosis [24, 33, 35] infections. IgG positivity to infections indicating exposure to dengue virus in 88% of 88 pregnant women was reported in one observational study [33], and toxoplasmosis and rubella in three of 28 women [24] in two case series/report.

Risk of bias assessment

We judged the overall risk of bias as fair or good for all the included case series/reports except one, which we rated as poor [25] due to selective reporting (Table 2).

Four of five observational studies included in the review were assigned an average quality rating of four to five stars based on the NOS. One observational study [22] was assigned a very low quality rating of one star as it provided sparse information (Table 3).

Discussion

Our systematic review describes the complications to fetuses and newborns have been reported during ZIKV infection in pregnant women. However, no study clearly described the history of maternal ZIKV infection and its effects on newborns of affected mothers. A lack of information on factors related to ZIKV infection in pregnancy further limits our understanding. Most studies were conducted in 2016, these studies focused on the presenting symptoms and associated complications in pregnant women and their fetuses/newborns. Relative to non-pregnant women or the general population [12, 39], symptoms and complications of ZIKV infection were comparable.

Maternal ZIKV infection tended to have more adverse effects on the fetus and the infant than on the mother, as most maternal symptoms were self-limiting. A broad spectrum of clinical presentation was observed in fetuses and newborns of ZIKV-infected mothers, ranging from normal to abnormal ultrasound findings during pregnancy, such as healthy newborns or newborns with an abnormality. A similar pattern was observed in ZIKV-infected pregnant women, ranging from symptomatic and asymptomatic clinical presentation to uncomplicated deliveries in most studies. Severe pregnancy-specific complications were uncommon and no maternal deaths were recorded. This highlights a challenge for both health providers and mothers at risk because of the increased likelihood of missed opportunities due to the frequent asymptomatic presentation.

The diagnostic accuracy of tests employed in the ZIKV context is still unclear [40] because existing studies are based on epidemiological models. In some women, ZIKV positivity was confirmed later in pregnancy, although the standard RT-PCR tests done in early trimesters were negative. Fetal ultrasound tests that were negative in the first and second trimesters were positive in late pregnancy stage [35]. The absolute risk of developing fetal abnormalities is also unclear, but microcephaly is unlikely being a rare condition.

ZIKV shares the same vector with other arboviruses including chikungunya and dengue. TORCH (Toxoplasmosis, Other (syphilis, varicella-zoster, parvovirus B19), Rubella, Cytomegalovirus (CMV), and Herpes) infections have been associated with congenital malformations including central nervous system anomalies. In the included reports, the absence of co-infection with or previous exposure to other viruses was established in most of the pregnant women. In some studies, IgG-positivity to dengue and toxoplasma were observed. Immunity to rubella and CMV were reported in some women with poor outcomes. Potential synergy due to the presence of immunity and/or seropositivity to other viruses could not be ascertained as clinical presentation varied from the absence of symptoms to the presence of typical symptoms seen in ZIKV-infected pregnant women. In one study, about half of the pregnant women who presented with rash had lymphadenopathy [33], a condition commonly observed in dengue infection due to lymphatic infiltration [41]. Although inconclusive, the history of lymphadenopathy in some pregnant women in this study in addition to the presentation of rash may show a possible role for dengue in extending the spectrum of maternal or fetal presentation. Indirect evidence from the history of viral infections that share similar characteristics and complications with ZIKV, such as CMV, may be important in understanding ZIKV infection.

In some studies, sample selection was based on the presenting clinical features. Limitation of the study population to only pregnant women presenting with features suggestive of ZIKV infection such as rash and fetuses with microcephaly as seen in some reports could be misleading. The rigorous search strategy, the inclusion of foreign language studies and exclusion of overlapping studies add to the strength of this review.

The broad spectrum of clinical presentation and complications in fetuses and newborns of ZIKV-infected pregnant women provides an insight into the potential liability for affected women, their families and health systems in resource-constrained settings. The possibility of an asymptomatic presentation proposes an emphasis on routine antenatal care and attention to signs of fetal brain abnormalities by health providers in pregnant women with molecular or epidemiological links to ZIKV infection.

Ongoing research on live animal models may help to understand the pathogenesis of ZIKV, with a potential for application to exposed pregnant cohorts. The rapid rate of emerging data from research on Zika virus infections in pregnancy and recent years proposes a need for frequent updates. As newer studies become available, further research on adverse pregnancy outcomes and implications on long-term consequences of ZIKV during pregnancy will further enable early diagnosis and better management modalities in provider care. Furthermore, personal protective measures should be encouraged.

Conclusions

This review highlights key evidence gaps that need to be urgently prioritized by the international community, more so, with the wide variations in fetal and newborn presentations/complications associated with prenatal ZIKV infection. Further research and comprehensive reporting of maternal ZIKV infection and fetal/neonatal complications may provide a better understanding of ZIKV infection in pregnancy and its attendant maternal/fetal complications. Such knowledge could inform the creation of effective and evidence-based strategies, guidelines, recommendations and health policies aimed at the management of maternal ZIKV infection.

Adherence to current best practices guidelines for prenatal care among health providers is encouraged. These include appropriate notification of suspected cases to the responsible authorities, long-term evaluation, monitoring and follow-up for newborns and infants exposed to ZIKV infection by a multidisciplinary team of health providers, more so, with ongoing variations in presentation and distribution of maternal ZIKV infection.

Abbreviations

- CENTRAL:

-

Cochrane Central Register of Controlled Trials

- CINAHL:

-

Cumulative index of nursing and allied health literature

- EMBASE:

-

Excerpta medica database

- IUGR:

-

Intrauterine growth restriction

- MEDLINE:

-

Medical literature analysis and retrieval system online

- PRISMA:

-

Preferred reporting items for systematic reviews and meta-analyses

- TORCH:

-

Toxoplasmosis, other (syphilis, varicella-zoster, parvovirus B19), rubella, cytomegalovirus (CMV), and herpes

- WHOGL:

-

World health organization global health library

- ZIKV:

-

Zika virus

References

Haddow A, Williams M, Woodall J, Simpson D, Goma L. Twelve isolations of Zika virus from Aedes (Stegomyia) africanus (Theobald) taken in and above a Uganda forest. Bull World Health Organ. 1964;31(1):57.

Dick G, Haddow A. Uganda S virus: A hitherto unrecorded virus isolated from mosquitoes in Uganda..(I). Isolation and pathogenicity. Trans R Soc Trop Med Hyg. 1952;46(6):600–18.

Kindhauser MK, Allen T, Frank V, Santhana RS, Dye C. Zika: the origin and spread of a mosquito-borne virus. Bull World Health Organ. 2016;94(9):675–686C. Epub 2016 Feb 9.

World Health Organization. Zika situation report: Zika and potential complications. 2016. Available from: URL: http://apps.who.int/iris/bitstream/10665/204371/1/zikasitrep_12Feb2016_eng.pdf [cited 2016, 18 April].

Macnamara F. Zika virus: a report on three cases of human infection during an epidemic of jaundice in Nigeria. Transactions of the Royal Society of Tropical Medicine and Hygiene. 1954;48(2):139–45.

Duffy MR, Chen T-H, Hancock WT, Powers AM, Kool JL, Lanciotti RS, et al. Zika virus outbreak on Yap Island, federated states of Micronesia. N Engl J Med. 2009;360(24):2536–43.

Gatherer D, Kohl A. Zika virus: A previously slow pandemic spreads rapidly through the Americas. J Gen Virol. 2016;97(2):269–73.

Paixao ES, Barreto F, da Gloria Teixeira M, da Conceicao N, Costa M, Rodrigues LC. History, Epidemiology, and Clinical Manifestations of Zika: A Systematic Review. Am J Public Health. 2016;106(4):606–12.

Cao-Lormeau V-M, Musso D. Emerging arboviruses in the Pacific. Lancet. 2014;384(9954):1571–2.

Eurosurveillance editorial team. Resources and latest news about zika virus disease available from ECDC. Euro Surveill. 2016;21(5):32.

Hills SL, Russell K, Hennessey M, Williams C, Oster AM, Fischer M, et al. Transmission of Zika Virus Through Sexual Contact with Travelers to Areas of Ongoing Transmission - Continental United States, 2016. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2016;65(8):215–6.

Goorhuis A, von Eije KJ, Douma RA, Rijnberg N, van Vugt M, Stijnis C, et al. Zika virus and the risk of imported infection in returned travelers: Implications for clinical care. Travel Med Infect Dis. 2016;14(1):13–5.

Fauci AS, Morens DM. Zika virus in the americas-yet another arbovirus threat. N Engl J Med. 2016;374(7):601–4.

Yakob L, Walker T. Zika virus outbreak in the Americas: the need for novel mosquito control methods. Lancet Glob Health. 2016;4(3):e148–e9.

Weaver SC, Reisen WK. Present and future arboviral threats. Antiviral research. 2010;85(2):328–45.

Chang C, Ortiz K, Ansari A, Gershwin ME. The Zika outbreak of the 21st century. J Autoimmun. 2016;68:1–13.

Victora CG, Schuler-Faccini L, Matijasevich A, Ribeiro E, Pessoa A, Barros FC. Microcephaly in Brazil: How to interpret reported numbers? The Lancet. 2016;387(10019):621–4.

National Heart, Lung and Blood Institute. Quality Assessment Tool for Case Series Studies. Available from National Institutes of Health: URL: https://www.nhlbi.nih.gov/health-pro/guidelines/in-develop/cardiovascularrisk-reduction/tools/case_series 2014. [cited 2016, 18 April].

Wells GA, Shea B, O’Connell D, Peterson J, Welch V, Losos M, et al. The Newcastle-Ottawa Scale (NOS) for assessing the quality if nonrandomized studies in meta-analyses. Available from: URL: http://www.ohri.ca/programs/clinical_epidemiology/oxford.htm 2012. [cited 2016, 18 April].

Chibueze EC, Parsons AJ, Ota E, Swa T, Oladapo OT, Mori R. Prophylactic antibiotics for manual removal of retained placenta during vaginal birth: a systematic review of observational studies and meta-analysis. BMC Pregnancy Childbirth. 2015;15(1):313.

Besnard M, Lastere S, Teissier A, Cao-Lormeau V, Musso D. Evidence of perinatal transmission of Zika virus, French Polynesia, December 2013 and February 2014. Euro Surveill. 2014;19(13).

McCarthy M. Severe eye damage in infants with microcephaly is presumed to be due to Zika virus. Bmj. 2016;352:i855.

Reyna-Villasmil E, Lopez-Sanchez G, Santos-Bolivar J. [Guillain-Barre syndrome due to Zika virus during pregnancy]. Med Clin (Barc). 2016;146(7):331–2. Sindrome de Guillain-Barre debido al virus del Zika durante el embarazo.

Villamil-Gómez WE, Mendoza-Guete A, Villalobos E, González-Arismendy E, Uribe-García AM, Castellanos JE, et al. Diagnosis, management and follow-up of pregnant women with Zika virus infection: A preliminary report of the ZIKERNCOL cohort study on Sincelejo, Colombia. Travel Medicine and Infectious Disease. 2016((Villamil-Gómez W.E.) Infectious Diseases and Infection Control Research Group, Hospital Universitario de Sincelejo, Sincelejo, Sucre, Colombia).

Thomas DL, Sharp TM, Torres J, Armstrong PA, Munoz-Jordan J, Ryff KR, et al. Local transmission of zika virus - Puerto Rico, november 23, 2015-january 28, 2016. MMWR MorbMortal Wkly Rep. 2016;65(6):154–8.

Schuler-Faccini L, Ribeiro EM, Feitosa IML, Horovitz DDG, Cavalcanti DP, Pessoa A, et al. Possible association between zika virus infection and microcephaly -- Brazil, 2015. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2016;65(3):59–62.

Brasil Martines R, Bhatnagar J, Kelly Keating M, Silva-Flannery L, Muehlenbachs A, Gary J, et al. Evidence of zika virus infection in brain and placental tissues from two congenitally infected newborns and two fetal losses - Brazil, 2015. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2016;65(6):159–60.

de Paula FB, de Oliveira Dias JR, Prazeres J, Sacramento GA, Ko AI, Maia M, et al. Ocular findings in infants with microcephaly associated with presumed Zika virus congenital infection in Salvador. Brazil JAMA ophthalmology. 2016;134(5):529–35.

Kleber de Oliveira W, Cortez-Escalante J, De Oliveira WTGH, do Carmo GMI, Henriques CMP, Coelho GE, et al. Increase in Reported Prevalence of Microcephaly in Infants Born to Women Living in Areas with Confirmed Zika Virus Transmission During the First Trimester of Pregnancy - Brazil, 2015. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2016;65(9):242–7.

Oliveira Melo AS, Malinger G, Ximenes R, Szejnfeld PO, Alves Sampaio S, Bispo de Filippis AM. Zika virus intrauterine infection causes fetal brain abnormality and microcephaly: tip of the iceberg? Ultrasound Obstet Gynecol. 2016;47(1):6–7.

Cauchemez S, Besnard M, Bompard P, Dub T, Guillemette-Artur P, Eyrolle-Guignot D, et al. Association between Zika virus and microcephaly in French Polynesia, 2013–15: a retrospective study. The Lancet. 2016;387(10033):2125–32.

Calvet G, Aguiar RS, Melo AS, Sampaio SA, de Filippis I, Fabri A, et al. Detection and sequencing of Zika virus from amniotic fluid of fetuses with microcephaly in Brazil: a case study. The Lancet Infectious diseases. 2016;16(6):653–60.

Brasil P, Pereira J, Jose P, Raja Gabaglia C, Damasceno L, Wakimoto M, Ribeiro Nogueira RM, et al. Zika virus infection in pregnant women in Rio de Janeiro—preliminary report. N Engl J Med. 2016;375:2321–34.

Ventura CV, Maia M, Ventura BV, Linden VVD, Araujo EB, Ramos RC, et al. Ophthalmological findings in infants with microcephaly and presumable intra-uterus Zika virus infection. Arq Bras Oftalmol. 2016;79(1):1–3.

Sarno M, Sacramento GA, Khouri R, do Rosario MS, Costa F, Archanjo G, et al. Zika Virus Infection and Stillbirths: A Case of Hydrops Fetalis, Hydranencephaly and Fetal Demise. PLoS Negl Trop Dis. 2016;10(2):e0004517.

Meaney-Delman D, Hills SL, Williams C, Galang RR, Iyengar P, Hennenfent AK, et al. Zika Virus Infection Among U.S. Pregnant Travelers - August 2015-February 2016. MMWR: Morbidity & Mortality Weekly Report. 2016;65(8):211–4.

Mlakar J, Korva M, Tul N, Popović M, PoIjšak-Prijatelj M, Mraz J, et al. Zika Virus Associated with Microcephaly. N Engl J Med. 2016;374(10):951–8.

Ventura CV, Maia M, Bravo-Filho V, Góis AL, Belfort R. Zika virus in Brazil and macular atrophy in a child with microcephaly. The Lancet. 2016;387(10015):228.

Zika virus infection: global update on epidemiology and potentially associated clinical manifestations. Wkly Epidemiol Rec. 2016;91(7):73–81.

Ioos S, Mallet H-P, Goffart IL, Gauthier V, Cardoso T, Herida M. Current Zika virus epidemiology and recent epidemics. Med Mal Infect. 2014;44(7):302–7.

Boeuf P, Drummer HE, Richards JS, Scoullar JS, Beeson JS. The global threat of Zika virus to pregnancy: epidemiology, clinical perspectives, mechanisms, and impact. BMC Medicine. 2016;14(1):112.

Acknowledgements

We are grateful to Chiemi Kataoka and Miwako Segawa for help with full text retrieval. We would also like to thank Dr. Julian Tang of the Department of Education for Clinical Research, National Center for Child Health and Development, for proofreading and editing this article.

Funding

The preparation of this review was financially supported by the UNDP/UNFPA/UNICEF/WHO/World Bank Special Programme of Research, Development and Research Training in Human Reproduction (HRP), Department of Reproductive Health and Research, World Health Organization; Research on Global Health Issues, Japan Agency for Medical Research and Development (AMED), Clinical Research Program for Child Health and Development from Japan Agency for Medical Research and Development (AMED) and the National Center for Child Health and Development (NCCHD).

Availability of data and materials

Systematic review registration, PROSPERO: CRD4201603969.

Authors’ contributions

OTO conceived the study. Hand-searching, screening, data extraction, was performed by ECC, VT, KSL, YT, OBO, AD, CN and NM. TS assisted with search strategy and conducted the search. RM and OTO gave guidance on project design, data extraction, and methodological assessments. ECC and VT drafted the manuscript. ECC, CN, NM, CM, EO, RM, and OTO revised and edited the manuscript. All authors read and approved the final manuscript for publication. The manuscript represents the views of the named authors only.

Competing interests

The review authors have no competing interests to declare.

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Ethics approval and consent to participate

Not applicable.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Additional files

Additional file 1:

Database search strategies for prenatal diagnosis of microcephaly in the context of ZIKV infection on March 3rd 2016. (DOCX 29 kb)

Additional file 2:

List of excluded studies ZIKV & pregnancy RHER1. (DOCX 31 kb)

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/), which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made. The Creative Commons Public Domain Dedication waiver (http://creativecommons.org/publicdomain/zero/1.0/) applies to the data made available in this article, unless otherwise stated.

About this article

Cite this article

Chibueze, E.C., Tirado, V., Lopes, K.d.S. et al. Zika virus infection in pregnancy: a systematic review of disease course and complications. Reprod Health 14, 28 (2017). https://doi.org/10.1186/s12978-017-0285-6

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/s12978-017-0285-6