Abstract

Background

MicroRNAs (miRNAs) are involved in the post-transcriptional regulation of genes. The objective of this study was to investigate whether select urinary cell-free microRNA’s may serve as biomarkers in children with active lupus nephritis (LN) and to assess their relationship to the recently identified combinatorial urine biomarkers, a.k.a. the LN-Panel (neutrophil gelatinase associated lipocalin, monocyte chemotactic protein 1, transferrin, and beta-trace protein).

Methods

miRNAs (125a, 127, 146a, 150 and 155) were measured using real-time polymerase chain reaction in the urine pellet (PEL) and supernatant (SUP) in 14 patients with active LN, 10 patients with active extra-renal lupus, and 10 controls. The concentrations of the LN-Panel biomarkers (neutrophil gelatinase associated lipocalin, monocyte chemotactic protein-1, transferrin, beta-trace protein) was assayed. Traditional laboratory and clinical measures of LN and lupus (complements, protein to creatinine ratio; Systemic Lupus Erythematosus Disease Activity Index) were also measured.

Results

All tested miRNAs in the SUP, but not the PEL, were associated with the LN-Panel biomarkers (0.3 < |r Pearson| < 0.73; p < 0.05), miRNA125a, miRNA127,miRNA146a also with C3 and dsDNA antibody levels (|r Pearson| > 0.24; p < 0.05), and miRNA146a with the renal domain of the SLEDAI (|r Pearson| = 0.32; p < 0.05). Mean miRNA levels of patients with active LN did not statistically (P > 0.05) differ from those of SLE patients without LN or controls.

Conclusion

Levels of cell-free miR-125a, miR-150, and miR-155 in the urine supernatant are associated with the expression of LN-Panel biomarkers and some LN measures. These miRNA’s may complement, but are unlikely superior to the LN-Panel for estimating concurrent LN activity.

Similar content being viewed by others

Background

Lupus nephritis (LN) continues to result in a significant morbidity and mortality [1, 2]. Current laboratory and clinical measures of kidney involvement with systemic lupus erythematosus (SLE) have been found unsuited to monitor the course of LN accurately, making effective LN therapy virtually impossible [3]. Therefore, there is active ongoing research to identify improved measures of LN activity which led to the discovery of several combinatorial urinary protein biomarkers a.k.a. the LN-Panel, consisting of neutrophil gelatinase associated lipocalin (NGAL), monocyte chemotactic protein 1 (MCP-1), transferrin (Tf), and beta trace protein (BTP; a.k.a lipocalin-like prostaglandin synthase). Earlier studies suggest that the LN-Panel can be used to diagnose active LN, anticipate LN flares [4–6].

MicroRNAs (miRNAs), small non-coding RNAs about 20 nucleotides in length, are involved in the gene expression at the post-transcriptional level [7]. MiRNAs regulate an estimated 30 % of the human protein-coding genome, including the expression of genes involved in inflammation. Because miRNAs are characterized by high stability in tissues and body fluids and protected from endogenous RNAses, they are attractive candidate biomarkers. Prior studies showed that there is differential expression of miRNAs in the various renal compartments, enabling discrimination of glomerular from tubulointerstitial inflammatory changes [8]. In this setting prior reports suggested that especially miRNA’s 125a, 127, 146a, 150 and 155 may be differentially expressed with inflammatory kidney diseases, SLE or LN [9–11].

The objective of this pilot study was to explore the potential of select cell-free miRNAs (125a, 127, 146a, 150 and 155) when measured in urine to serve as LN biomarkers.

Methods

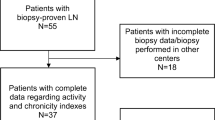

With the approval of the institutional review board and after all the necessary consents and assents were obtained, we studied patients diagnosed with SLE prior to age 18 years [12] and a control with juvenile idiopathic arthritis (JIA) or fibromyalgia in this prospective cohort study. While SLE patients were studied every 6 months for up to three visits, controls were asked to participate in only one study visit.

At enrollment all SLE patient needed to have either active LN (LN-group) or active extra-renal SLE (SLE-group) as measured by the SLE Disease Activity Index (SLEDAI; score range of 0–105) [13]. Active LN was defined as a renal SLEDAI domain score of ≥ 8 in patients with biopsy-diagnosed LN (LN-Group), while active extra-renal SLE was defined presence of a SLEDAI score ≥ 8, excluding the renal domain items (proteinuria, hematuria, pyuria, cellular urine casts). Additionally, for including in the SLE-group, patients had to lack a history of LN and have minimum disease duration of two year.

LN and SLE measures

At each study visit of SLE patients the SLEDAI was completed. The renal domain scores served as a clinical measure of LN activity (SLE-renal; score range 0–16) and the remaining items were used to calculate an extrarenal SLE activity score (SLEDAI-extrarenal; score range 0–89). We also measured the renal domain score of the BILAG index as previously reported (BILAG-renal, range 0–12) [14]. We also recorded complement C3 and C4 levels, anti-dsDNA antibodies titer, amount of proteinuria as estimated by the protein to creatinine (P/C) ratio in a random urine sample, serum creatinine, and the glomerular filtration rate (GFR) as estimated by the modified Schwartz formula [15].

Laboratory assays for miRNA measurement and the LN-Panel

miRNA determination

A single dose of urine preservative (Norgen Biotek, Ontario, Canada) was added to each urine sample that was intended for miRNA measurement prior to centrifugation at 4000 g for 20 min to pellet the cells. We then separated the urine sample to urine supernatant (SUP) and urine pellet (PEL). Then the urine PEL and SUP samples were frozen within 2 h of urine collection and stored at −80 °C until the time of batch.

Five candidate miRNAs (125a, 127, 146a, 150 and 155 ) were selected based upon their proposed involvement in the pathogenesis of lupus and kidney disease [10]. The mirRNeasy Mini Kit (Qiagen, Valencia, CA) was used for miRNA isolation from both the SUP and the PEL. As a spike-in control, 5 μl of C. elegans-miR-39 were added to each 5 ml aliquot of SUP and PEL. This was followed by miRNA concentration measurements, using TaqMan miR Real time PCR technology (Life technologies, Carlsbad, CA). Till date, no reliable or validated endogenous control miRNA has been established to normalize for the miRNA content. We have used RNU48 as the housekeeping miRNA to severe as reference standard. The data were analyzed using the ∆∆CT method [16]. The miRNA levels and the analysis shown are unadjusted to the urine creatinine as adjusted analysis was the same.

LN-Panel biomarkers

We measured urinary concentrations of Tf and BTP by immunonephelometry (Dade Behring Prospect, Marburg, Germany). Intra and inter-assay coefficients of variation (CV) of this assay were 3.4 % and 2.5 % for Tf and 2.3 % and 6.5 % for BTP. Urine concentrations of MCP-1 were measured by enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (ELISA) (Human MCP-1, R&D Systems, Minneapolis, MN, USA). The respective intra-assay and inter-assay CV was 5.0 % and 5.1 %. NGAL levels were quantified by ELISA (Kit 036; AntibodyShop, Grusbakken, Denmark). Intra and inter-assay CV of NGAL were 5.0 % and 5.1 %. Urine creatinine measurements were made using a modified Jaffe reaction, and microalbumin (MALB) was measured by immunoturbidimetry, both on a Dimension Xp and plus HM Clinical Analyzer (Siemens, Munich, Germany). Coefficients of variability for the creatinine measurements were 2.4 % (intra) and 4.2 % (total), and 2.9 % (intra) and 5.9 % (inter) for MALB. TGF-β [CV inter/intra: 2.6 %/8.3 %] was measured by ELISA (R&D Systems, Minneapolis, MN) after acid activation. Briefly, 20 μL of 1 N HCl was added to 100 μL of urine sample, mixed by inversion and incubated at room temperature for 10 min. Next, the acidified sample was neutralized by adding 20 μL of 1.2 N NaOH/0.5 M HEPES, then the assay was immediately run per manufacturer’s instructions [CV inter/intra: 2.0 %/7.8 %].

All the urine biomarkers were normalized to urine creatinine (in mg/mL). Laboratory personnel measuring the urinary biomarkers were blinded to the clinical information.

Statistical analysis

Urine levels of the LN-Panel biomarkers and the miRNAs were considered primary measures in this study. They were log-transformed in order to fit major assumptions of parametric statistical models in analyses. For each miRNA measure, its change over time was assessed using a mixed-effect model, adjusting for controlling covariates, mainly the demographics. Other numerical variables were summarized by geometric mean ± SE (standard error) values, and binary or categorical variables were summarized with frequency values (in %). Groups of patients were assessed for statistically significant differences using analysis of variance (ANOVA). Associations between miRNA measures, LN-Panel markers and other LN measures (SLEDAI, complement levels, GFR, serum creatinine) were assessed using Pearson’s correlation coefficients (r) which can be interpreted as follows: between 0.2 and 0.39 is considered to be weak, 0.4 and 0.59 is considered moderate, 0.6 and 0.79 is strong, and 0.8 to 1.00 is a very strong correlation [17]. Excel XP (Microsoft, Redmond, WA) and SAS 9.4 (SAS Institute, Cary, NC) programs were used for analysis. Two-sided P values less than 0.05 were considered significant.

Results

Characteristics of patients

The demographic information of the participants is summarized in Table 1. There were 39 visits (baseline and follow up visits) for the LN-group and 29 visits for the SLE-group available for analysis. Majority of the LN patients had Class 4 (50 %) followed by Class 2 (28.6 %) as per the International Society of Nephrology/Renal Pathology Society Classification for LN [18]. Controls with JIA were treated with non-steroidal anti-inflammatory medications (n = 2), methotrexate (MTX, n = 2) or etanercept plus MTX (n = 1). None of the fibromyalgia patients was treated with anti-inflammatory medications.

Levels of candidate miRNAs

The mean urine concentrations of the miRNAs considered were statistically significantly higher in the PEL than the SUP in all groups, including controls (p < 0.05). However, as is summarized in Table 2, there were no significant (P > 0.05) differences in any of the miRNA concentrations between the SLE-group and the LN-group, or controls, irrespective of whether considering the supernatant or the pellet. There was merely a trend towards higher levels of miR-127 in the SUP of the SLE-group compared to the LN-group. Notably, miRNA levels lacked association with patient age, sex and race (p > 0.05).

Association of candidate miRNAs with other LN measures

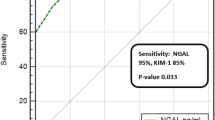

When measured in the PEL all of the miRNA had weaker association to all of the LN and SLE measures than miRNAs measured in the SUP. Table 3 summarizes associations between miRNA levels in the SUP with SLE and LN outcomes (Table 3). All of the LN-Panel biomarkers were positively associated with SUP values of miR125a and miR150 (0.4 < r ≤ 0.73; P < 0.05), while miRNA127 and miRNA155 lacked association with NGAL but still were weakly to moderately associated with the other LN-Panel biomarkers (TF, BTP, MCP-1).

Besides miRNA127, all of the other miRNA when measured in the SUP were associated with LN activity (SLEDAI-renal; BILAG-renal), but correlations where generally weaker than those of the LN-Panel biomarkers (Table 3). Notable neither SUP miRNA levels nor the LN-Panel biomarkers were related to SLEDAI-extrarenal scores.

MiRNA levels and the course of LN

When examining miRNA levels over the course of LN activity (renal-SLEDAI), only miR-146a in the SUP showed a trend towards lower levels with worsening of LN activity, and a trend towards higher levels with improving LN activity (both P > 0.05). None of the other miRNAs (miR125a, miR 127, miR 150, miR 155) was found to have a consistent trend with the course of activity.

Discussion

We found closer relationships between the levels of cell-free miRNAs when measured in the urine supernatant than the pellet with the presence of LN. Notably, the urine concentrations of previously described protein biomarkers a.k.a. the LN-Panel were more closely related to the clinical presentation of LN than the cell-free miRNA biomarkers considered in this pilot study.

Though the miRNAs 125a, 127, 146a, 150 and 155 are produced by various kidney cells and free miRNA may stem from circulation or urine, we failed to document strong association with these miRNAs in the pellet with either the extra-renal SLEDAI, renal –SLEDAI or the traditional laboratory measures.

A potential explanation for observing some relationships of miRNA’s with LN activity in the supernatant, but not the pellet is that these detected miRNA in the pellet may not reflect miRNA from the kidney, but rather from cells of the external urinary canal. For that reason, we advocate that measurement of miRNA’s in the urine should be done from supernatant and not the pellet. We found urine miR-127 to be higher in the LN group compared to the SLE group. Although this difference was not statistically significant, our findings were similar to Dai R et al. who reported miR-127 to be upregulated in the splenocytes of Lpr mice [19]. More studies are still needed to fully understand the significance of miR-127 in LN.

Bench studies showed that the select miRNA have crucial roles in regulating the immune response in the pathogenesis of LN, either negatively like miR-146a and 155 or positively like miR-150 [10, 20]. When examining these miRNAs for their potential to serve as clinical biomarkers in the urine, our cross-sectional and longitudinal data indicate that only miR-146a had a weak association with the renal–SLEDAI and changed with the course of LN activity. This is in line with some previous studies [20, 21]. However, none of the other miRNA measured were associated with clinical or laboratory measures of LN activity.

We have shown that the levels of miR125a, miR150 and miR155 had associations with the levels of the LN-panel biomarkers namely BTP, MCP-1 and Tf. These protein biomarkers have been proven to be accurate biomarkers of LN activity in previous studies [6, 22]. Possible hypotheses to the association that we see between select miRNA’s and the LN-Panel that these three miRNA’s may have an important role in regulating the LN –Panel protein biomarkers or indeed associated with LN activity, but due low subject number , no significant association was found. Our results indicate that these selected cell-free miRNAs are unlikely superior to the LN-Panel as clinical biomarkers for LN activity, and may be inferior based on performance of the LN-Panel of having stronger associations with the LN activity compared to the selected miRNA’s.

Also extracting the miRNAs from the urine compared to the LN-Panel markers, are time consuming and assays have not yet been standardized.

Some limitations of this study are there could be some racial or gender differences that has been previously reported, but we were not able to find them possibly due to low subjects included [23]. Also our study examined the role of only five miRNA’s and the values of other miRNAs at large to serve as biomarkers for LN cannot be fully excluded. Nonetheless, our study is still valuable as we tested five highly relevant miRNAs reported for LN. For future studies on miRNA as biomarkers, the use of the high-throughput capacity technology offered by arrays will be an excellent approach option, since hundreds of miRNAs can be studied simultaneously. Another limitation is till date, there has been no reliable or validated endogenous control miRNA established to normalize for the miRNA content in the urine. We used RNU48, as it has been found to be a suitable housekeeping miRNAs in urothelial and endometrial carcinomas and most likely it will be suitable in the urine as well [24, 25] .

Our miRNA levels in the SUP and the PEL were generally very low compared to those usually found in the blood. To be able to isolate larger amount of miRNA’s in the urine we conducted a small pilot study (n = 7), using similar patients, but instead of extracting free floating total RNA from urine, we extracted them from exosomes by differntial centrifugation of the urine . Exosomes are small membrane vesicles with a size of 30–120 nm that are released by different cell types. Exosomes can be isolated from various body fluids. Lin-Li Lv et al. found that the detection of miRNA from the exosomes were stable and reproducible [26]. In line with this report, our pilot data support that harvesting miRNA from urine exosomes yields considerable higher amounts of miRNA than the cell-free urine, and by doing so we may be able to detect better and more valid associations.

Conclusions

Translational research on miRNA in LN is still in its infancy. Our study in testing these five urinary cell-free miRNA’s (125a, 127, 146a, 150 and 155) to serve as biomarkers in LN appears less promising despite the proven relationship of these miRNA’s to the pathogenesis of SLE. Still further studies are needed and necessary to include a more differentially regulated miRNA in patients with LN and to examine their correlation in the urine.

Abbreviations

- BTP:

-

beta-trace protein

- CV:

-

coefficients of variation

- JIA:

-

juvenile idiopathic arthritis

- LN:

-

Panel Lupus Nephritis Panel

- LN:

-

Lupus Nephritis

- MCP1:

-

monocyte chemotactic protein 1

- miRNA:

-

MicroRNA

- NGAL:

-

neutrophil gelatinase associated lipocalin

- PEL:

-

pellet

- SLE:

-

Systemic Lupus Erythematosus

- SLEDAI:

-

SLE Disease Activity Index

- SUP:

-

supernatant

- Tf:

-

transferrin

References

Costenbader KH, Desai A, Alarcon GS, Hiraki LT, Shaykevich T, Brookhart MA, et al. Trends in the incidence, demographics, and outcomes of end-stage renal disease due to lupus nephritis in the US from 1995 to 2006. Arthritis Rheum. 2011;63(6):1681–8.

Hiraki LT, Lu B, Alexander SR, Shaykevich T, Alarcon GS, Solomon DH, et al. End-stage renal disease due to lupus nephritis among children in the US, 1995–2006. Arthritis Rheum. 2011;63(7):1988–97.

Reich HN, Landolt-Marticorena C, Boutros PC, John R, Wither J, Fortin PR, et al. Molecular markers of injury in kidney biopsy specimens of patients with lupus nephritis. J Mol Diagn. 2011;13(2):143–51.

Suzuki M, Wiers K, Brooks EB, Greis KD, Haines K, Klein-Gitelman MS, et al. Initial validation of a novel protein biomarker panel for active pediatric lupus nephritis. Pediatr Res. 2009;65(5):530–6.

Rovin BH, Song H, Birmingham DJ, Hebert LA, Yu CY, Nagaraja HN. Urine chemokines as biomarkers of human systemic lupus erythematosus activity. J Am Soc Nephrol. 2005;16(2):467–73.

Brunner HI, Bennett MR, Mina R, Suzuki M, Petri M, Kiani AN, et al. Association of noninvasively measured renal protein biomarkers with histologic features of lupus nephritis. Arthritis Rheum. 2012;64(8):2687–97.

Almeida MI, Reis RM, Calin GA. MicroRNA history: Discovery, recent applications, and next frontiers. Mutat Res. 2011;717(1–2):1–8.

Saal S, Harvey SJ. MicroRNAs and the kidney: coming of age. Curr Opin Nephrol Hypertens. 2009;18(4):317–23.

Zhou H, Cheruvanky A, Hu X, Matsumoto T, Hiramatsu N, Cho ME, et al. Urinary exosomal transcription factors, a new class of biomarkers for renal disease. Kidney Int. 2008;74(5):613–21.

Zan H, Tat C, Casali P. MicroRNAs in lupus. Autoimmunity. 2014;47(4):272–85.

Liang M, Liu Y, Mladinov D, Cowley Jr AW, Trivedi H, Fang Y, et al. MicroRNA: a new frontier in kidney and blood pressure research. Am J Physiol Renal Physiol. 2009;297(3):F553–8.

Eilertsen GO, Becker-Merok A, Nossent JC. The influence of the 1997 updated classification criteria for systemic lupus erythematosus: epidemiology, disease presentation, and patient management. J Rheumatol. 2009;36(3):552–9.

Gladman DD, Ibanez D, Urowitz MB. Systemic lupus erythematosus disease activity index 2000. J Rheumatol. 2002;29(2):288–91.

Brunner HI, Bennett M, Abulaban K, Klein-Gitelman M, O’Neil K, Tucker L, et al. Development of a novel renal activity index of lupus nephritis in children & young adults. Arthritis Care Res. 2015.10.1002/acr.22762

Schwartz GJ, Haycock GB, Edelmann Jr CM, Spitzer A. A simple estimate of glomerular filtration rate in children derived from body length and plasma creatinine. Pediatrics. 1976;58(2):259–63.

Schmittgen TD, Livak KJ. Analyzing real-time PCR data by the comparative C(T) method. Nat Protoc. 2008;3(6):1101–8.

Mukaka MM. Statistics corner: A guide to appropriate use of correlation coefficient in medical research. Malawi Med J. 2012;24(3):69–71.

Weening JJ, D’Agati VD, Schwartz MM, Seshan SV, Alpers CE, Appel GB, et al. The classification of glomerulonephritis in systemic lupus erythematosus revisited. J Am Soc Nephrol. 2004;15(2):241–50.

Dai R, McReynolds S, Leroith T, Heid B, Liang Z, Ahmed SA. Sex differences in the expression of lupus-associated miRNAs in splenocytes from lupus-prone NZB/WF1 mice. Biol Sex Differ. 2013;4(1):19.

Shen N, Liang D, Tang Y, de Vries N, Tak PP. MicroRNAs--novel regulators of systemic lupus erythematosus pathogenesis. Nat Rev Rheumatol. 2012;8(12):701–9.

Wang G, Tam LS, Li EK, Kwan BC, Chow KM, Luk CC, et al. Serum and urinary cell-free MiR-146a and MiR-155 in patients with systemic lupus erythematosus. J Rheumatol. 2010;37(12):2516–22.

Hinze CH, Suzuki M, Klein-Gitelman M, Passo MH, Olson J, Singer NG, et al. Neutrophil gelatinase-associated lipocalin is a predictor of the course of global and renal childhood-onset systemic lupus erythematosus disease activity. Arthritis Rheum. 2009;60(9):2772–81.

Kwekel JC, Vijay V, Desai VG, Moland CL, Fuscoe JC. Age and sex differences in kidney microRNA expression during the life span of F344 rats. Biol Sex Differ. 2015;6(1):1.

Ratert N, Meyer HA, Jung M, Mollenkopf HJ, Wagner I, Miller K, et al. Reference miRNAs for miRNAome analysis of urothelial carcinomas. PLoS One. 2012;7(6):e39309.

Torres A, Torres K, Wdowiak P, Paszkowski T, Maciejewski R. Selection and validation of endogenous controls for microRNA expression studies in endometrioid endometrial cancer tissues. Gynecol Oncol. 2013;130(3):588–94.

Lv LL, Cao Y, Liu D, Xu M, Liu H, Tang RN, et al. Isolation and quantification of microRNAs from urinary exosomes/microvesicles for biomarker discovery. Int J Biol Sci. 2013;9(10):1021–31.

Acknowledgement

This study was supported by the Lupus foundation of America (65641255) and the Center for the Clinical and Translational Science and Training (CCTST) of the University of Cincinnati. The funders had no role in study design, data collection and analysis, decision to publish, or preparation of the manuscript. This study was approved by the institutional review board of Cincinnati Children’s hospital and Medical Center. We would also like to acknowledge Melanie Hlalol and Kasha Wiley (Cincinnati Children’s Hospital, OH) for data management. PD, HBR and MB are supported by P50 DK096418. We also acknowledge Drs Michael Henrickson, Jennifer Huggins and Tracey Ting for referring patients to the study.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Additional information

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Authors’ contributions

KA as corresponding author was responsible for conception, coordination and design of the study and has written drafted and critically revised the manuscript. NF performed the miRNA isolation and performed the PCR experiments including data evaluation, interpretation and drafting the manuscript. RN was responsible for data collection and drafting the manuscript. JY was involved in data analysis and manuscript drafting. PD was involved in conception and design of the study and critically revised the manuscript as well as the data evaluation and interpretation. AG critically revised the manuscript as well as the data evaluation and interpretation. MB performed the LN-panel PCR and was critically involved in drafting the manuscript. SA was involved in conception and design of the study and critically revised the manuscript as well as the data evaluation and interpretation. HB was also was involved in conception and design of the study and critically revised the manuscript as well as the data evaluation and interpretation. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/), which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made. The Creative Commons Public Domain Dedication waiver (http://creativecommons.org/publicdomain/zero/1.0/) applies to the data made available in this article, unless otherwise stated.

About this article

Cite this article

Abulaban, K.M., Fall, N., Nunna, R. et al. Relationship of cell-free urine MicroRNA with lupus nephritis in children. Pediatr Rheumatol 14, 4 (2016). https://doi.org/10.1186/s12969-016-0064-x

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/s12969-016-0064-x