Abstract

Background

The impact of integrated lifestyles on health has attracted a lot of attention. It remains unclear whether adherence to low-risk healthy lifestyle factors is protective in individuals with metabolic syndrome and metabolic syndrome-like characteristics. We aimed to explore whether and to what extent overall lifestyle scores mitigate the risk of all-cause mortality in individuals with metabolic syndrome and metabolic syndrome-like characteristics.

Methods

In total, 6934 participants from the 2007 to 2014 National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey (NHANES) were included. The weighted healthy lifestyle score was constructed based on smoking, alcohol consumption, physical activity, diet, sleep duration, and sedentary behavior information. Generalized linear regression models and restricted cubic splines were used to analyze the association between healthy lifestyle scores and all-cause mortality.

Results

Compared to participants with relatively low healthy lifestyle scores, the risk ratio (RR) in the middle healthy lifestyle score group was 0.51 (RR = 0.51, 95% CI 0.30–0.88), and the high score group was 0.26 (RR = 0.26, 95% CI 0.15–0.48) in the population with metabolic syndrome. The difference in gender persists. In females, the RRs of the middle and high score groups were 0.47 (RR = 0.47, 95% CI 0.23–0.96) and 0.21 (RR = 0.21, 95% CI 0.09–0.46), respectively. In males, by contrast, the protective effect of a healthy lifestyle was more pronounced in the high score group (RR = 0.33, 95% CI 0.13–0.83) and in females, the protective effects were found to be more likely. The protective effect of a healthy lifestyle on mortality was more pronounced in those aged < 65 years. Higher lifestyle scores were associated with more prominent protective effects, regardless of the presence of one metabolic syndrome factor or a combination of several factors in 15 groups. What's more, the protective effect of an emerging healthy lifestyle was more pronounced than that of a conventional lifestyle.

Conclusions

Adherence to an emerging healthy lifestyle can reduce the risk of all-cause mortality in people with metabolic syndrome and metabolic syndrome-like characteristics; the higher the score, the more obvious the protective effect. Our study highlights lifestyle modification as a highly effective nonpharmacological approach that deserves further generalization.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Chronic diseases are contributing to an increasing global disease burden. In recent years, metabolic syndrome (MetS) has become a major global health problem and has received much attention, as it is closely related to various mortality outcomes [1, 2]. The first formal definition of metabolic syndrome was developed by the World Health Organization (WHO) in 1998 [3]. The International Diabetes Federation (IDF) and American Heart Association/National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute (AHA/NHLBI) reached a consensus on the definition of metabolic syndrome in recent years [4]. Metabolic syndrome is a group of disorders that include central obesity, elevated triglycerides, reduced high-density lipoprotein cholesterol (HDL-C), high blood pressure, and elevated fasting glucose; the presence of three or more of these five characteristics is called metabolic syndrome [4,5,6]. Each disease itself is a risk factor for other conditions. However, the combination of these diseases greatly increases the chance of developing potentially life-threatening conditions such as type 2 diabetes mellitus, cardiovascular disease (CVD), or stroke [7,8,9]. The health risks also increase when the number of components increases [7]. Metabolic syndrome typically begins with insulin resistance, and its pathogenesis involves oxidative stress and activation of the renin-angiotensin system [10]. High glucose can increase cardiotoxicity and reduce the effectiveness of anticancer drugs by activating the NLRP3 inflammasome and a large number of cytokines [11]. Metabolic syndrome is affected by a mixture of genetic and behavioral factors, and lifestyle interventions are often ignored in favor of medication [5, 12]. Nevertheless, lifestyle changes can be a simple and achievable way to delay the development of a disease.

Lifestyle factors can cause several chronic diseases. Accumulating evidence suggests that the management of a healthy lifestyle is becoming increasingly important [13, 14]. Conventional modifiable lifestyle factors, namely no current smoking, moderate alcohol consumption, regular physical activity, and a healthy diet, have received sufficient attention in previous studies [15,16,17]. However, new lifestyle factors have also been discussed, such as less sedentary behavior and adequate sleep duration [18, 19]. There have been many studies on the relationship between conventional lifestyles and mortality. However, evidence of the combination of conventional and emerging lifestyles is lacking, especially in people with metabolic syndrome and metabolic syndrome-like characteristics. Multiple studies have focused on the lifestyle factors of the general population or even specific populations, such as people with type 2 diabetes or neurodegenerative diseases [18, 20]. With regard to people with multiple comorbidities of metabolic syndrome, this area of research remains largely unexplored.

To fill this knowledge gap, we included participants from the National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey (NHANES) to examine whether six newly emerging healthy lifestyles could reduce the risk of all-cause mortality in people with metabolic syndrome and those with metabolic syndrome-like characteristics. We also wanted to determine how much a healthy lifestyle might affect outcomes. Furthermore, we wondered whether the effect of adherence to a relatively low-risk lifestyle on mortality varied depending on different combinations of metabolic syndrome characteristics.

Methods

Study population

The NHANES is a major program of the National Center for Health Statistics (NCHS). It was designed to assess the health and nutritional status of adults and children in the United States. Written informed consent was obtained from all the participants. It began in the early 1960s and became a continuous program in 1999. It combines interviews and physical examinations and is based on a two-year survey cycle. The survey is conducted annually on a nationally representative sample of approximately 5000 people and oversampled for specific age and ethnic groups. Patient identifiers are not available in the publicly available NHANES database.

A total of 29,573 participants from the NHANES 2007–2014 were included in the study. Of these 29,573 participants, we excluded those who were younger than 18 years of age (n = 4841), pregnant or lactating (n = 371), had unreliable or missing follow-up information (n = 881), had cancer or cardiovascular disease at baseline (n = 5008), and had missing values on lifestyle scores (n = 11,538), leaving 6934 participants in the final analysis (Fig. 1).

Metabolic syndrome refers to a group of diseases with three or more of the following features, including central obesity, elevated triglycerides, reduced high-density lipoprotein cholesterol, high blood pressure, and elevated fasting glucose. High triglycerides and reduced HDL levels are collectively referred to as abnormal lipid metabolism. In addition, we grouped metabolic syndrome into four essential features: central obesity, dyslipidemia, hypertension, and hyperglycemia. We further divided the participants into those with metabolic syndrome and 15 groups with metabolic syndrome characteristics. We performed possible combinations based on the four main features of the metabolic syndrome, including those of any one feature (central obesity group, dyslipidemia group, hypertension group, and hyperglycemia group), combinations of two features (central obesity and dyslipidemia group, central obesity and hypertension group, central obesity and hyperglycemia group, dyslipidemia and hypertension group, dyslipidemia and hyperglycemia group, hypertension and hyperglycemia group), combinations of three features (central obesity, dyslipidemia and hypertension group, central obesity, dyslipidemia, and hyperglycemia group, central obesity, hypertension, and hyperglycemia group, dyslipidemia, hypertension, and hyperglycemia group), and all four features (central obesity, dyslipidemia, hypertension, and hyperglycemia group), for a total of 15 groups.

Healthy lifestyle score

Information on the lifestyles of participants was obtained using self-reported questionnaires. In this study, in addition to conventional healthy lifestyle factors (no smoking, moderate alcohol consumption, moderate to vigorous physical activity, and high-quality diet), we incorporated emerging behavioral factors (sleep duration and sedentary behavior) [21, 22]. A detailed definition of a healthy lifestyle is provided in the Additional file 1 [16,17,18, 23,24,25,26,27,28,29].

We assigned a score of one to a healthy lifestyle and zero to an unhealthy lifestyle. To better reflect the effect of each healthy lifestyle factor on the outcome, we constructed a healthy lifestyle score by calculating a weighted healthy lifestyle score [30]. To avoid extreme groups, we divided the lifestyle scores into three groups, which were divided into thirds.

Covariates

Socioeconomic factor-related covariates were mainly obtained from home interviews in the form of questionnaires. They included age, sex, ethnicity, education, and the income-to-poverty ratio (PIR). Ethnic groups were mainly divided into five groups: Mexican Americans, other Hispanics, non-Hispanic white, non-Hispanic black, and other races. Education was categorized into less than high school diploma, high school graduate or equivalent, some college or associate degree, and college or above. The PIR was divided into three groups based on the following criteria: ≤ 1.0, PIR > 1.0, PIR ≤ 3.0, and PIR > 3.0.

Other covariates included the laboratory data. Blood specimens were processed, stored, and transported to the Fairview Medical Center Laboratory at the University of Minnesota, Minneapolis, MN, USA, for analysis. The staff were well trained, and the NCHS developed and distributed a quality control protocol to each NHANES contract laboratory. Because the criteria for characterizing metabolic syndrome included values for triglycerides and HDL, we did not include either indicator in our model.

Assessment of the outcomes

The NCHS links data collected by population surveys to death certificate records in the National Death Index (NDI). Public use linked mortality files (LMF) includes a limited set of variables, applies only to adult participants, and is subject to data perturbation techniques to reduce the risk of participant disclosure. The publicly available LMF includes follow-up data on mortality from the date the participants entered the survey until December 31, 2019, which is the most recent data available. The data released for public use include the addition of perturbative data for two elements: the date of death and the cause of death. For more information on accessing the restricted use linked mortality files, please refer to the official website (https://www.cdc.gov/nchs/data-linkage). The National Database of Death Statistics is a central database of death record information archived in judicial vital records or statistical offices and maintained by the National Center for Vital Statistics. Participants were deemed eligible for mortality follow-up if sufficient information was provided during the interview or at the mobile examination center (MEC) follow-up. These data can be used to determine the cause and manner of death for each person who died. Basic and multiple causes of death were classified according to the International Classification of Diseases, Ninth Revision (ICD-9), and Tenth Revision (ICD-10) since 1999. This study defined the outcome as all-cause mortality (heart disease, cancer, chronic lower respiratory disease, unintentional injuries, and cerebrovascular diseases).

Statistical analysis

Data were analyzed according to the guidelines provided by the NHANES. Baseline characteristic variables were expressed as n (%) if they were categorical, as the mean (SD) for normally distributed variables, or as the median (interquartile range) for non-normally distributed variables. The study population was divided into three groups according to lifestyle scores for between-group analysis. The Chi-square test, ANOVA, and Kruskal–Wallis test were used to compare the distribution of baseline characteristics among the different lifestyle score groups [18].

Generalized linear regression models and restricted cubic splines were used to analyze the association between healthy lifestyle scores and all-cause mortality risk [31]. The results were presented as risk ratios (RRs) with 95% confidence intervals (CI). Three regression models were constructed to account for the influence of confounding factors: model 1 included age and sex; model 2 additionally included ethnicity, education, and PIR; and model 3 additionally included HbA1c% levels. According to the weighted healthy lifestyle score, patients were divided into three levels: low, middle, and high. Age (< 65 years and ≥ 65 years) and sex stratification analyses were performed. We also examined the association between healthy lifestyle scores and all-cause mortality among participants with metabolic syndrome. Based on the aforementioned grouping, we examined different combinations of the basic characteristics of total metabolic function and a population with all the basic characteristics so that 15 groups were included in the analysis.

Sensitivity analyses were also conducted. We calculated the conventional healthy lifestyle score and compared it with the emerging healthy lifestyle score in the overall population, males, and females. Data analysis was performed using STATA 16, and p < 0.05 was considered statistically significant [32].

Results

Characteristics of the participants

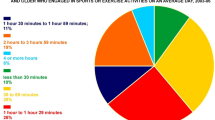

A total of 6934 participants were enrolled in this study. In total, 295 deaths were recorded. Based on their weighted healthy lifestyle scores, they were classified into three groups: low (n = 2561, 36.93%), middle (n = 2076, 29.94%), and high (n = 2297, 33.13%). The baseline characteristics of the study participants are shown in Table 1. In contrast to the low lifestyle score group, the high lifestyle score group had a greater proportion of older people. In terms of population distribution, non-Hispanic whites accounted for the largest proportion. The lowest PIR was found in the group with the lowest healthy lifestyle score, indicating the highest level of poverty. The proportion of people with a college degree or above was the lowest in the low lifestyle score group. With an increase in the score, the proportion of smokers decreased. There were no current smokers in the high score group. Changes in diet and sedentary behavior among the three groups were most pronounced as the scores increased.

Association of emerging healthy lifestyle factors and all-cause mortality

During the follow-up, 129 deaths were recorded. Based on the definition of metabolic syndrome, we finally included 1697 individuals for analysis to explore the association of the weighted healthy lifestyle score with all-cause mortality by performing generalized linear regression analyses. As shown in Table 2, the relative risk of all-cause mortality decreased as the lifestyle score increased. In model 1, after adjusting for age and sex, compared with participants with a relatively low healthy lifestyle, the RR of the middle group was 0.51 (RR = 0.51, 95% CI 0.30–0.88), and the high group was 0.26 (RR = 0.26, 95% CI 0.15–0.48). In model 2, adjusted for age, sex, ethnicity, education, and PIR, the RR was 0.55 (RR = 0.55, 95% CI 0.32–0.94) for the middle group and 0.27 (RR = 0.27, 95% CI 0.15–0.48) for the high score group compared with the low score group. And in model 3, after adjusting additionally included HbA1c% levels, the multivariate-adjusted RR of the middle group was 0.56 (RR = 0.56, 95% CI 0.33–0.97), and the high group was 0.26 (RR = 0.26, 95% CI 0.14–0.47).

Subgroup analyses

Similar results were obtained in stratified analyses by sex and age. The impact of a healthy lifestyle on the relative risk of mortality from any cause is more pronounced among females. As shown in Table 2, in females, the RRs of the middle score group and the high score group were 0.47 (RR = 0.47, 95% CI 0.23–0.96) and 0.21 (RR = 0.21, 95% CI 0.09–0.46), respectively, when compared with the low score group in model 1. When additional covariates were adjusted, only the RRs of the high group were statistically significant, with 0.21 (RR = 0.21, 95% CI 0.09–0.47) in model 2 and 0.19 (RR = 0.19, 95% CI 0.08–0.44) in model 3. In the analysis performed with males, the protective effect of a healthy lifestyle was more pronounced only in the high score group (model 1: RR = 0.33, 95% CI 0.13–0.83, model 2: RR = 0.35, 95% CI 0.14–0.88, model 3: RR = 0.33, 95% CI 0.13–0.85). We divided the participants into two groups according to whether they were under or over 65 years old and performed stratified analyses. The protective effect of a healthy lifestyle on mortality was more evident in people younger than 65 years than in those older than 65 years. Moreover, the older the age, the higher the lifestyle score required to play a significant protective role.

Association of emerging healthy lifestyle factors and all-cause mortality in people with metabolic syndrome-like characteristics

Participants with features of metabolic syndrome, that is, one of the following four features or a combination of two, three, or four of them, were included in the analysis. We performed population-wide and sex-stratified analyses within these 15 groups. As shown in Figs. 2 and 3, in general, a higher lifestyle score was associated with a more obvious protective effect, regardless of the presence of one of the metabolic syndrome factors or a combination of several factors, and this was true for both males and females. In the dyslipidemia and hypertension groups, only the high score group had a reduced risk of all-cause mortality, with an RR of 0.29 (RR = 0.29, 95% CI 0.16–0.51) and 0.53 (RR = 0.53, 95% CI 0.33–0.85), respectively. The middle and high lifestyle scores were not statistically significant in the central obesity group. Interestingly, in the hyperglycemia group, the RR was higher in the high score group (RR = 0.43, 95% CI 0.22–0.84) than in the middle score group (RR = 0.26, 95% CI 0.12–0.59). In most cases, it was found to be easier for female patients to achieve meaningful results. There was no statistically significant difference in the group of patients with central obesity and hypertension when the patients had two features of metabolic syndrome. When the patients had three characteristics of metabolic syndrome, the high score group had a reduced RR compared with the middle and low score groups.

Relationship between participants with metabolic syndrome-like characteristics and all-cause mortality in the middle score group. A RRs in all population; B RRs in males; C RRs in females; a represents the characteristics of central obesity, b represents the characteristics of dyslipidemia, c represents the characteristics of hypertension, and d represents the characteristics of hyperglycemia

Relationship between participants with metabolic syndrome-like characteristics and all-cause mortality in the high score group. A RRs in all population; B RRs in males; C RRs in females; a represents the characteristics of central obesity, b represents the characteristics of dyslipidemia, c represents the characteristics of hypertension, and d represents the characteristics of hyperglycemia

The dose–response relationship between a healthy lifestyle and all-cause mortality is shown in Fig. 4. In general, the healthy lifestyle score showed a nonlinear negative correlation with all-cause mortality with a relatively flat curve. As the score increased, the risk of all-cause mortality decreased. This negative nonlinear relationship became significant in all populations when the score exceeded 61.6. We further performed dose–response analyses for both males and females. Among females, a score above 63.7 was needed for a negative relationship to become statistically significant, whereas the relationship was not significant among males.

Sensitivity analyses

The results did not change in the sensitivity analyses. The conventional lifestyle score reduced the risk of all-cause mortality among all the population with metabolic syndrome, particularly with a significant effect in the group with a high score (RR = 0.44, 95% CI 0.24–0.79), and again, it was meaningful among females. In addition, the protective effect of the newly emerging healthy lifestyle factors was stronger, and the RR was lower than that of the conventional lifestyle factors, both in the whole population and in females (Fig. 5).

Comparison of the conventional and emerging healthy lifestyle scores. A Comparison in the middle score group; B comparison in the high score group. Of the two groups represented by the same legend, the one on the left represents the emerging healthy lifestyle group, and the one on the right represents the conventional healthy lifestyle group

Discussion

In this prospective cohort study, we investigated the association between lifestyle scores based on six low-risk lifestyle factors and all-cause mortality in patients with metabolic syndrome and metabolic syndrome-like characteristics. A weighted score was constructed to reflect the effect of each lifestyle factor on the outcome. As a result, compared with the low-weighted score group, the middle group had a reduced risk of all-cause mortality, and the high group had a further reduced risk regardless of socioeconomic factors and biochemical indicators. We found consistent results when sex- and age-stratified analyses were performed. To the best of our knowledge, this is the first prospective study to explore the relationship between emerging healthy lifestyles and all-cause mortality in patients with metabolic syndrome. Our study adds to this field by examining the impact of multiple behavior-related risk factors on health and simultaneously shows that the findings are relatively consistent with those of previous studies. This study sheds new light on health management and primary prevention in populations with metabolic syndrome and metabolic syndrome-like characteristics.

A healthy lifestyle reduces the burden of disease and prolongs the life span of the population [33, 34]. People with higher healthy lifestyle scores were more likely to have higher levels of education and lower poverty, indicating that a healthy lifestyle is influenced by many economic and social factors. People with high scores tend to be older, possibly because they have more time to pay attention and improve their lifestyles. The lifestyle behaviors that differed most across groups were diet, sedentary behavior, and sleep duration, which may require longer adherence than other lifestyle behaviors. In the three models that we constructed, the protective effect of a healthy lifestyle persisted as the number of covariates increased. Studies on conventional healthy lifestyles have been previously conducted. Our study is consistent with the results of previous cohort studies conducted in the United States and the United Kingdom [16,17,18, 30, 35]. For example, Li et al. showed that adherence to a healthy lifestyle was associated with a longer life expectancy free of major chronic diseases in two cohorts from the United States [16]. In a study by Zhang et al., a healthy lifestyle was shown to be associated with a lower risk of mortality and cardiovascular disease burden in two large cohorts, one from the United States and one from the United Kingdom [17]. Consistent with previous studies, a low-risk lifestyle was associated with a protective effect against mortality, with RRs further decreasing as the weighted healthy lifestyle score increased.

Additionally, the association between a healthy lifestyle and mortality has been studied in different populations. Chudasama et al. showed that adherence to a healthy lifestyle could improve life expectancy in people with multimorbidity [30]. In individuals with type 2 diabetes, a low-risk lifestyle was also found to be protective [18]. In some central nervous system diseases such as stroke, previous studies have shown similar conclusions [20]. Dhana et al. reported that a comprehensive lifestyle is associated with a lower risk of developing Alzheimer’s disease [36]. A favorable lifestyle is associated with a lower risk of developing dementia even in people with a high genetic risk [37]. Recent epidemiological studies have highlighted the significance of comprehensive dietary patterns rather than single nutritional elements [38]. Study has shown that a proper diet can regulate metabolism through a variety of ways and has anti-inflammatory effects, and can significantly reduce the incidence of metabolic syndrome [39]. In this study, we adopted the widely used HEI-2015 to integrally reflect the intake of various nutritional elements. Recent studies have shown that sleep patterns can reduce the risk of all-cause and cause-specific mortality in several large cohort studies [28, 40, 41]. In addition to sleep, increasing attention has been paid to the evaluation of sedentary behavior in a composite healthy lifestyle. Less sedentary behavior is related to a reduced risk of premature mortality and cardiovascular disease mortality [42, 43]. On this basis, studies that include conventional healthy lifestyle factors in addition to emerging healthy lifestyle factors are rare [18]. The sensitivity analysis showed that the six new healthy lifestyle factors had a more significant protective effect on mortality outcomes than the four conventional healthy lifestyle factors.

Dietary intake information on individual food intake is available in NHANES. However, it is usually the 24-h dietary recall of total nutrient intake that is widely used in research because it is convenient and easy to calculate [27]. Some studies calculated participants' exercise levels by wearing an accelerometer [44]. But relatively few people obtained the amount of exercise by this method, so we chose the variable with the largest number of participants, the metabolic equivalent of the task. For example, only participants from 2011 to 2014 were tested for body movement by wearing accelerators. However, we had access to questionnaire information for participants from 2007 to 2014. Previous studies have defined “never smoking” as a healthy level [16]. However, we believe that this criterion is somewhat harsh. Therefore, in this study, we define “no current smoking” as a healthy level. There are also studies that use “never drinking” as a healthy standard [45]. We believe that people will inevitably drink alcohol throughout their lives, so we choose “non-heavy drinking” as a standard of health.

With the introduction of the concept of metabolic syndrome, it has attracted increasing attention. There are a considerable number of patients with metabolic syndrome. Patients with chronic diseases are more likely to have metabolic syndrome [46]. Moreover, when patients have metabolic syndrome or metabolic syndrome-like characteristics in combination with other underlying conditions, such as heart disease and cancer, the risk of death is increased [11]. In vitro studies have confirmed that high glucose, one of the characteristics of metabolic syndrome, increases cardiotoxicity and reduces the effectiveness of anticancer drugs through inflammatory pathways, and that inflammatory factors play an important role in heart failure in cancer patients [11]. However, few relevant studies on the primary prevention of metabolic syndrome have been conducted. The treatment of metabolic syndrome needs to be individualized, especially pharmacotherapy. Lifestyle modification is a relatively simple treatment without drug side effects. In this study, we concluded that a high lifestyle score is associated with a reduced risk of all-cause mortality in people with metabolic syndrome and those with features of metabolic syndrome. Compared to people with central obesity, those with dyslipidemia and hypertension could significantly reduce their risk of all-cause mortality through a favorable lifestyle, especially those with dyslipidemia. Among those with more than two features of metabolic syndrome, those with central obesity required a higher lifestyle score to reduce the risk of all-cause mortality. In people with metabolic syndrome, the proportion of patients with central obesity has been reported to be > 80% [5, 47]. The relationships between central obesity and other metabolic risk factors are different and they interact with each other. Most researchers agree that obesity is influenced by epigenetic, genetic, and lifestyle factors [48, 49]. Therefore, we speculate that patients with central obesity should adopt a healthier lifestyle to reduce the interference of epigenetic and genetic factors. Curiously, we observed that in the hyperglycemic group, a high healthy lifestyle score was associated with a higher risk ratio. The management of diabetes relies on self-management as well as medication [50]. Additionally, the severity of diabetes and medication use can affect the impact of a healthy lifestyle. Because a healthy lifestyle requires long-term adherence, we reasoned that the effects of a healthy lifestyle may become apparent over time with a longer follow-up period. Although the protective effect of high lifestyle scores was observed in males and females, the differences between males and females persisted. Our results showed that females appeared to be more strongly associated with a lower risk of death associated with a healthy lifestyle, similar to previous studies [16, 51, 52]. However, the specific reason for this remains unclear.

The strengths of our study include rich resource information and a long and reliable follow-up, which made it possible to perform a full analysis of mortality. The NHANES provides detailed and repeated measures of relevant lifestyle factors, which makes our results sufficiently dependable. Our results were further improved and confirmed after adjusting for socioeconomic factors and biochemical indicators using a multivariate covariate adjusted generalized linear regression model. Additionally, a series of sensitivity analyses made our results more robust. This study, based on a large population and a long follow-up period, helps people with metabolic syndrome and metabolic syndrome-like characteristics make the right choices. Our study also has several limitations, such as the number of subjects included and limited follow-up time. In addition, the target population of the NHANES is the non-institutionalized civilian resident of the United States; therefore, our findings may not be generalizable to other populations, and further research is needed.

Conclusion

In aggregate, this study confirmed that a middle weighted healthy lifestyle score was associated with a lower risk of all-cause mortality than a low score, and that a high score was associated with further reduced risk among people with metabolic syndrome and those with features of metabolic syndrome. People with central obesity and other features of metabolic syndrome often require greater effort to adopt healthier lifestyles to achieve favorable outcomes. Moreover, the protective effect of the emerging healthy lifestyle factors was stronger than that of conventional healthy lifestyle factors, which is a notable finding. Our study provides a basis for further strengthening the management of patients with metabolic syndrome to reduce the global burden. A healthy lifestyle can be used as a simple nonpharmacological treatment without side effects and deserves to be promoted and popularized. In addition, our study suggests that future work should focus more on the management of people with central obesity. And efforts are needed to promote and disseminate adequate sleep duration and less sedentary behavior, two lifestyle factors that vary widely across populations.

Availability of data and materials

Data for this study are available at https://www.cdc.gov/nchs/nhanes/index.htm.

Abbreviations

- CI:

-

Confidence intervals

- CVD:

-

Cardiovascular disease

- HDL:

-

High-density lipoprotein

- HEI:

-

Healthy eating index

- LDL:

-

Low-density lipoprotein

- NCHS:

-

National Center for Health Statistics

- NHANES:

-

National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey

- PIR:

-

Income-to-poverty ratio

- RR:

-

Risk ratio

References

Saklayen MG. The global epidemic of the metabolic syndrome. Curr Hypertens Rep. 2018;20:12.

Khunti K, Davies M. Metabolic syndrome. BMJ. 2005;331:1153–4.

Alberti KG, Zimmet PZ. Definition, diagnosis and classification of diabetes mellitus and its complications. Part 1: diagnosis and classification of diabetes mellitus provisional report of a WHO consultation. Diabet Med. 1998;15:539–53.

Alberti KG, Eckel RH, Grundy SM, Zimmet PZ, Cleeman JI, Donato KA, Fruchart JC, James WP, Loria CM, Smith SC Jr, et al. Harmonizing the metabolic syndrome: a joint interim statement of the International Diabetes Federation Task Force on Epidemiology and Prevention; National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute; American Heart Association; World Heart Federation; International Atherosclerosis Society; and International Association for the Study of Obesity. Circulation. 2009;120:1640–5.

Nilsson PM, Tuomilehto J, Rydén L. The metabolic syndrome—what is it and how should it be managed? Eur J Prev Cardiol. 2019;26:33–46.

Prasun P. Mitochondrial dysfunction in metabolic syndrome. Biochim Biophys Acta Mol Basis Dis. 2020;1866: 165838.

Lorenzo C, Williams K, Hunt KJ, Haffner SM. The National Cholesterol Education Program—Adult Treatment Panel III, International Diabetes Federation, and World Health Organization definitions of the metabolic syndrome as predictors of incident cardiovascular disease and diabetes. Diabetes Care. 2007;30:8–13.

Bozkurt B, Aguilar D, Deswal A, Dunbar SB, Francis GS, Horwich T, Jessup M, Kosiborod M, Pritchett AM, Ramasubbu K, et al. Contributory risk and management of comorbidities of hypertension, obesity, diabetes mellitus, hyperlipidemia, and metabolic syndrome in chronic heart failure: a scientific statement from the American Heart Association. Circulation. 2016;134:e535–78.

Mottillo S, Filion KB, Genest J, Joseph L, Pilote L, Poirier P, Rinfret S, Schiffrin EL, Eisenberg MJ. The metabolic syndrome and cardiovascular risk a systematic review and meta-analysis. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2010;56:1113–32.

Hsu CN, Hou CY, Hsu WH, Tain YL. Early-life origins of metabolic syndrome: mechanisms and preventive aspects. int J Mol Sci. 2021;22:11872.

Quagliariello V, De Laurentiis M, Cocco S, Rea G, Bonelli A, Caronna A, Lombari MC, Conforti G, Berretta M, Botti G, Maurea N. NLRP3 as putative marker of ipilimumab-induced cardiotoxicity in the presence of hyperglycemia in estrogen-responsive and triple-negative breast cancer cells. Int J Mol Sci. 2020;21:7802.

Myers J, Kokkinos P, Nyelin E. Physical activity, cardiorespiratory fitness, and the metabolic syndrome. Nutrients. 2019;11:1652.

Doughty KN, Del Pilar NX, Audette A, Katz DL. Lifestyle medicine and the management of cardiovascular disease. Curr Cardiol Rep. 2017;19:116.

Kushner RF, Sorensen KW. Lifestyle medicine: the future of chronic disease management. Curr Opin Endocrinol Diabetes Obes. 2013;20:389–95.

Kelly JT, Su G, Zhang L, Qin X, Marshall S, Gonzalez-Ortiz A, Clase CM, Campbell KL, Xu H, Carrero JJ. Modifiable lifestyle factors for primary prevention of CKD: a systematic review and meta-analysis. J Am Soc Nephrol. 2021;32:239–53.

Li Y, Schoufour J, Wang DD, Dhana K, Pan A, Liu X, Song M, Liu G, Shin HJ, Sun Q, et al. Healthy lifestyle and life expectancy free of cancer, cardiovascular disease, and type 2 diabetes: prospective cohort study. BMJ. 2020;368: l6669.

Zhang YB, Chen C, Pan XF, Guo J, Li Y, Franco OH, Liu G, Pan A. Associations of healthy lifestyle and socioeconomic status with mortality and incident cardiovascular disease: two prospective cohort studies. BMJ. 2021;373: n604.

Han H, Cao Y, Feng C, Zheng Y, Dhana K, Zhu S, Shang C, Yuan C, Zong G. Association of a healthy lifestyle with all-cause and cause-specific mortality among individuals with type 2 diabetes: a prospective study in UK Biobank. Diabetes Care. 2022;45:319–29.

Livingstone KM, Abbott G, Ward J, Bowe SJ. Unhealthy lifestyle, genetics and risk of cardiovascular disease and mortality in 76,958 individuals from the UK Biobank Cohort Study. Nutrients. 2021;13:4283.

Lv J, Yu C, Guo Y, Bian Z, Yang L, Chen Y, Tang X, Zhang W, Qian Y, Huang Y, et al. Adherence to healthy lifestyle and cardiovascular diseases in the Chinese population. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2017;69:1116–25.

Ford ES, Zhao G, Tsai J, Li C. Low-risk lifestyle behaviors and all-cause mortality: findings from the National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey III Mortality Study. Am J Public Health. 2011;101:1922–9.

Wang B, Wang N, Sun Y, Tan X, Zhang J, Lu Y. Association of combined healthy lifestyle factors with incident dementia in patients with type 2 diabetes. Neurology. 2022;99:e2336–45.

Khera AV, Emdin CA, Drake I, Natarajan P, Bick AG, Cook NR, Chasman DI, Baber U, Mehran R, Rader DJ, et al. Genetic risk, adherence to a healthy lifestyle, and coronary disease. N Engl J Med. 2016;375:2349–58.

Song Z, Yang R, Wang W, Huang N, Zhuang Z, Han Y, Qi L, Xu M, Tang YD, Huang T. Association of healthy lifestyle including a healthy sleep pattern with incident type 2 diabetes mellitus among individuals with hypertension. Cardiovasc Diabetol. 2021;20:239.

Arnett DK, Blumenthal RS, Albert MA, Buroker AB, Goldberger ZD, Hahn EJ, Himmelfarb CD, Khera A, Lloyd-Jones D, McEvoy JW, et al. 2019 ACC/AHA Guideline on the primary prevention of cardiovascular disease: executive summary: a report of the American College of Cardiology/American Heart Association Task Force on Clinical Practice Guidelines. Circulation. 2019;140:e563–95.

Krebs-Smith SM, Pannucci TE, Subar AF, Kirkpatrick SI, Lerman JL, Tooze JA, Wilson MM, Reedy J. Update of the Healthy Eating Index: HEI-2015. J Acad Nutr Diet. 2018;118:1591–602.

Chen F, Du M, Blumberg JB, Ho Chui KK, Ruan M, Rogers G, Shan Z, Zeng L, Zhang FF. Association among dietary supplement use, nutrient intake, and mortality among U.S. adults: a cohort study. Ann Intern Med. 2019;170:604–13.

Zhou T, Yuan Y, Xue Q, Li X, Wang M, Ma H, Heianza Y, Qi L. Adherence to a healthy sleep pattern is associated with lower risks of all-cause, cardiovascular and cancer-specific mortality. J Intern Med. 2022;291:64–71.

Kelly NA, Soroka O, Onyebeke C, Pinheiro LC, Banerjee S, Safford MM, Goyal P. Association of healthy lifestyle and all-cause mortality according to medication burden. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2022;70:415–28.

Chudasama YV, Khunti K, Gillies CL, Dhalwani NN, Davies MJ, Yates T, Zaccardi F. Healthy lifestyle and life expectancy in people with multimorbidity in the UK Biobank: a longitudinal cohort study. PLoS Med. 2020;17: e1003332.

Wu D, Gao X, Shi Y, Wang H, Wang W, Li Y, Zheng Z. Association between handgrip strength and the systemic immune-inflammation index: a nationwide study, NHANES 2011–2014. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2022;19:13616.

Rahman EU, Chobufo MD, Farah F, Mohamed T, Elhamdani M, Rueda C, Aronow WS, Fonarow GC, Thompson E. Prevalence and temporal trends of anemia in patients with heart failure. QJM. 2022;115:437–41.

Zhang X, Lu J, Wu C, Cui J, Wu Y, Hu A, Li J, Li X. Healthy lifestyle behaviours and all-cause and cardiovascular mortality among 0.9 million Chinese adults. Int J Behav Nutr Phys Act. 2021;18:162.

Chiuve SE, Rexrode KM, Spiegelman D, Logroscino G, Manson JE, Rimm EB. Primary prevention of stroke by healthy lifestyle. Circulation. 2008;118:947–54.

Rutten-Jacobs LC, Larsson SC, Malik R, Rannikmae K, MEGASTROKE consortium, International Stroke Genetics Consortium, Sudlow CL, Dichgans M, Markus HS, Traylor M. Genetic risk, incident stroke, and the benefits of adhering to a healthy lifestyle: cohort study of 306 473 UK Biobank participants. BMJ. 2018;363: k4168.

Dhana K, Evans DA, Rajan KB, Bennett DA, Morris MC. Healthy lifestyle and the risk of Alzheimer dementia: findings from 2 longitudinal studies. Neurology. 2020;95:e374–83.

Lourida I, Hannon E, Littlejohns TJ, Langa KM, Hypponen E, Kuzma E, Llewellyn DJ. Association of lifestyle and genetic risk with incidence of dementia. JAMA. 2019;322:430–7.

Cespedes EM, Hu FB. Dietary patterns: from nutritional epidemiologic analysis to national guidelines. Am J Clin Nutr. 2015;101:899–900.

Quagliariello V, D’Aiuto G, Iaffaioli RV, Berretta M, Buccolo S, Iovine M, Paccone A, Cerrone F, Bonanno S, Nunnari G, et al. Reasons why COVID-19 survivors should follow dietary World Cancer Research Fund/American Institute for Cancer Research (WCRF/AICR) recommendations: from hyper-inflammation to cardiac dysfunctions. Eur Rev Med Pharmacol Sci. 2021;25:3898–907.

Fan M, Sun D, Zhou T, Heianza Y, Lv J, Li L, Qi L. Sleep patterns, genetic susceptibility, and incident cardiovascular disease: a prospective study of 385 292 UK biobank participants. Eur Heart J. 2020;41:1182–9.

Song Q, Wang M, Zhou T, Sun D, Ma H, Li X, Heianza Y, Qi L. The lifestyle-related cardiovascular risk is modified by sleep patterns. Mayo Clin Proc. 2022;97:519–30.

Ekelund U, Tarp J, Steene-Johannessen J, Hansen BH, Jefferis B, Fagerland MW, Whincup P, Diaz KM, Hooker SP, Chernofsky A, et al. Dose-response associations between accelerometry measured physical activity and sedentary time and all cause mortality: systematic review and harmonised meta-analysis. BMJ. 2019;366: l4570.

Stamatakis E, Gale J, Bauman A, Ekelund U, Hamer M, Ding D. Sitting time, physical activity, and risk of mortality in adults. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2019;73:2062–72.

Troiano RP, Berrigan D, Dodd KW, Masse LC, Tilert T, McDowell M. Physical activity in the United States measured by accelerometer. Med Sci Sports Exerc. 2008;40:181–8.

Jia J, Zhao T, Liu Z, Liang Y, Li F, Li Y, Liu W, Li F, Shi S, Zhou C, et al. Association between healthy lifestyle and memory decline in older adults: 10 year, population based, prospective cohort study. BMJ. 2023;380: e072691.

Karamzad N, Izadi N, Sanaie S, Ahmadian E, Eftekhari A, Sullman MJM, Safiri S. Asthma and metabolic syndrome: a comprehensive systematic review and meta-analysis of observational studies. J Cardiovasc Thorac Res. 2020;12:120–8.

Wong ND, Pio JR, Franklin SS, L’Italien GJ, Kamath TV, Williams GR. Preventing coronary events by optimal control of blood pressure and lipids in patients with the metabolic syndrome. Am J Cardiol. 2003;91:1421–6.

Safaei M, Sundararajan EA, Driss M, Boulila W, Shapi’i A. A systematic literature review on obesity: understanding the causes & consequences of obesity and reviewing various machine learning approaches used to predict obesity. Comput Biol Med. 2021;136: 104754.

Goodarzi MO. Genetics of obesity: what genetic association studies have taught us about the biology of obesity and its complications. Lancet Diabetes Endocrinol. 2018;6:223–36.

American Diabetes A. Standards of medical care in diabetes-2020 abridged for primary care providers. Clin Diabetes. 2020;38:10–38.

O’Doherty MG, Cairns K, O’Neill V, Lamrock F, Jorgensen T, Brenner H, Schottker B, Wilsgaard T, Siganos G, Kuulasmaa K, et al. Effect of major lifestyle risk factors, independent and jointly, on life expectancy with and without cardiovascular disease: results from the Consortium on Health and Ageing Network of Cohorts in Europe and the United States (CHANCES). Eur J Epidemiol. 2016;31:455–68.

Stenholm S, Head J, Kivimaki M, Kawachi I, Aalto V, Zins M, Goldberg M, Zaninotto P, Magnuson Hanson L, Westerlund H, Vahtera J. Smoking, physical inactivity and obesity as predictors of healthy and disease-free life expectancy between ages 50 and 75: a multicohort study. Int J Epidemiol. 2016;45:1260–70.

Acknowledgements

We thank the participants and the staff of NHANES for their dedications and contributions.

Funding

This study was supported by Natural Science Foundation of Shandong Province (ZR2020MH138).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

MYN and JHC designed the study and conducted the data analysis. MYN drafted the manuscript. RYH, YS, QX, XDP, and XYZ proposed critical revisions to the manuscript. All included authors made contributions to the manuscript and approved the version submitted. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Corresponding authors

Ethics declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate

NHANES is conducted by the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) and the National Center for Health Statistics (NCHS). And the NHANES study protocol was reviewed and approved by the NCHS Research Ethics Review Committee. All participants in NHANES provided written informed consent.

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary Information

Additional file 1: Table S1.

Detailed definition of a healthy lifestyle. Table S2. HEI–2015 Components and Scoring Standards.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/. The Creative Commons Public Domain Dedication waiver (http://creativecommons.org/publicdomain/zero/1.0/) applies to the data made available in this article, unless otherwise stated in a credit line to the data.

About this article

Cite this article

Niu, M., Chen, J., Hou, R. et al. Emerging healthy lifestyle factors and all-cause mortality among people with metabolic syndrome and metabolic syndrome-like characteristics in NHANES. J Transl Med 21, 239 (2023). https://doi.org/10.1186/s12967-023-04062-1

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/s12967-023-04062-1