Abstract

Background

To develop a machine learning model for predicting acute respiratory distress syndrome (ARDS) events through commonly available parameters, including baseline characteristics and clinical and laboratory parameters.

Methods

A secondary analysis of a multi-centre prospective observational cohort study from five hospitals in Beijing, China, was conducted from January 1, 2011, to August 31, 2014. A total of 296 patients at risk for developing ARDS admitted to medical intensive care units (ICUs) were included. We applied a random forest approach to identify the best set of predictors out of 42 variables measured on day 1 of admission.

Results

All patients were randomly divided into training (80%) and testing (20%) sets. Additionally, these patients were followed daily and assessed according to the Berlin definition. The model obtained an average area under the receiver operating characteristic (ROC) curve (AUC) of 0.82 and yielded a predictive accuracy of 83%. For the first time, four new biomarkers were included in the model: decreased minimum haematocrit, glucose, and sodium and increased minimum white blood cell (WBC) count.

Conclusions

This newly established machine learning-based model shows good predictive ability in Chinese patients with ARDS. External validation studies are necessary to confirm the generalisability of our approach across populations and treatment practices.

Similar content being viewed by others

Background

Acute respiratory distress syndrome (ARDS) is a clinical syndrome characterised by tachypnoea, severe hypoxemia, decreased respiratory compliance, and lung tissue damage evident on chest radiographs [1]. Although diffuse alveolar damage is the core pathological process [2], the diagnoses of ARDS and its milder form, acute lung injury (ALI), are based on clinical characterisation. The clinical standards for ALI/ARDS were revised in 2012 and are known as the “Berlin definition” [3]. ARDS is responsible for more than 2 million critical care days and 75,000 deaths in the USA yearly [4] and is associated with an overall mortality ranging from 35 to 50% [5]. Specific and sensitive means of diagnosing ALI/ARDS early are missing, and once diagnosed, it tends to progress quickly. A large number of basic and clinical studies have demonstrated that early diagnosis and intervention are key to improving the survival rate of patients with ARDS [6]. Although it is equally important to predict ARDS events, so far, there have been no reports of models for predicting such cases. Therefore, there is a pressing need for the development and clinical testing of a predictive model for ARDS events, which might improve the clinical diagnosis of ARDS.

According to the 2001 National Institutes of Health definition, a biomarker is “a characteristic that is objectively measured and evaluated as an indicator of normal biological processes, pathogenic processes, or pharmacologic responses to a therapeutic intervention” [7]. Biomarkers reflect pathophysiological mechanisms and, as such, may help in the recognition of ARDS. Combining existing clinical definitions with reliable biomarkers may therefore enhance the diagnosis of ARDS. In addition to the recognition of ARDS, biomarkers may contribute to risk stratification and the prediction of outcomes or serve as surrogate endpoints to monitor interventions [8]. The proposed advantages of biomarkers [8], together with the limited reliability and validity of the American–European Consensus Criteria (AECC) criteria [9, 10], have spurred the search for reliable ARDS biomarkers during the last two decades. Many biomarkers for the diagnosis of ARDS have been found, such as the receptor for advanced glycation end-products (RAGE), angiopoietin-2 (Ang-2), surfactant protein D (SP-D) and inflammatory factors [interleukin (IL)-6, IL-8, and tumour necrosis factor-α (TNF-α)] [11, 12]. However, no sensitive and specific clinical biomarkers for ARDS have been found [13].

In this secondary analysis of a prospective and independent cohort study, the primary goal was to find several new biomarkers that differ from the previously studied biomarkers for ARDS and to establish a reliable predictive model for ARDS events that includes these new biomarkers.

Methods

Study population and ARDS definition

This study was a secondary analysis of a prospective observational study [14] conducted from January 1, 2011, to August 31, 2014, in five intensive care units (ICUs) in the Beijing metropolitan area: Peking University Third Hospital northwest of Beijing, Beijing Friendship Hospital to the south, Beijing Shijitan Hospital in the center, Beijing Xiyuan Hospital to the west, and China–Japan Friendship Hospital in the northeast (Clinicaltrials.gov Identifier: NCT02944279).

Each ICU admission was screened for eligible participants. The exclusion criteria were age < 18 years; history of chronic lung diseases, such as pulmonary fibrosis or bronchiolitis; history of pneumonectomy; treatment with immunomodulating therapy other than corticosteroids, such as granulocyte colony stimulating factor, cyclophosphamide, cyclosporine, interferon, or TNFα antagonists; presence of other immunodeficient conditions, such as HIV infection, leukaemia, or neutropenia (absolute neutrophil count < 1000/mL); history of organ or bone marrow transplants other than an autologous bone marrow transplant; directive to withhold intubation; ICU stay duration < 72 h; or development of ARDS before ICU admission. Patients at risk for developing ARDS were defined as critically ill patients with at least one of the following conditions predisposing them to developing ARDS: sepsis; septic shock; trauma; pneumonia; aspiration (indicated inhalation of gastric juice, fresh water, seawater, amniotic fluid, etc.); massive transfusion of packed red blood cells (PRBCs; defined as > 8 PRBC units in the 24-h period prior to admission); or severe pancreatitis. After selection, patients at risk for developing ARDS were followed daily and assessed according to the Berlin definition [3]. All patients were followed until hospital discharge or death within 60 days from the first day of study enrolment. The full methodological details of this cohort study have been previously published [14]. In this secondary analysis, we used only the variables from the first day of admission before the patient developed ARDS to build this prediction model. In addition, for several variables, such as heart rate, respiratory rate, temperature, glucose, haematocrit, and sodium, we used only the minimum or maximum value from multiple measurements. The ensemble model was written in the Python scripting language (version 3.6.5, Python Software Foundation, Wilmington, DE, USA, https://www.python.org).

Statistical analysis

The binary variables are described as counts and percentages and were evaluated by the Chi-squared test or Fisher’s exact test. Continuous variables of each group are presented as the mean ± SEM. Student’s t-test was used to compare the normally distributed continuous variables; otherwise, the Mann–Whitney U test was used. P < 0.05 was considered statistically significant. All analyses were performed using SPSS 21.0 (SPSS, Chicago, IL).

Predictive model development

In this study, we aimed to construct an ensemble model called a random forest model that consisted of a population of decision-tree classifiers. In the forest, each decision-tree classifier was built with a bootstrap sample of features and independent observations. As a result, random forests can avoid overfitting and yield an overall improved model with a high predictive accuracy because the randomness makes the model less sensitive to variation [15]. Notably, the implementation of the combination used in this study replaces voting on each decision-tree classifier by averaging their probabilistic prediction to decrease the variance [16,17,18]. In general, there are two key parameters used in the design of random forests: (i) the number of decision trees and (ii) the size of the random subsets of features. In most cases, more trees in the forest produce more robust predictive accuracy but require a longer computation time. The latter controls the trade-off between variance and bias. From empirical and clinical research, the number of decision trees and the size of the random subset are set to 100 and the square root of the number of features, respectively. The whole process of constructing a random forest algorithm can be described briefly by the following steps: (i) select “k” features from the training set as a subset; (ii) calculate the node by using the best split among the “k” features; (iii) create child nodes by using the best split; (iv) repeat from step (i) to step (iii) until the iteration ending conditions (the iteration of the above process repeated 1000 times) are met; and (iv) repeat from step (i) to step (iv) until 100 decision trees are archived. After building the random forest, the predictions are made with testing data by using the average of these individual tree outputs. The ensemble model was written in the Python scripting language (version 3.6.5, Python Software Foundation, Wilmington, DE, USA, https://www.python.org). The 296 selected patients were randomly divided into training (ARDS = 76 and non-ARDS = 160) and testing (ARDS = 15 and non-ARDS = 45) sets at a ratio of 4:1. The training set was used to build the ensemble model, while the testing set was used to evaluate the predictive performance of the model. In this study, the ensemble random forest algorithm was also used to predict the accuracy of the models based on different subsets of features. Because the relative rank of each feature could be used to reflect the relative importance of features to the ratings of overall prediction performance [16,17,18], we applied a random forest algorithm to rank the contribution of each feature, constructed models on the feature subspaces and provided a comparison of the corresponding model quality scores using testing data. In addition to the classification accuracy and the area under the receiver operating characteristic (ROC) curve (AUC), the Matthews correlation coefficient (MCC) and F-measure (\( F_{1} \)) were also used to evaluate the performance of the constructed model.

Here, \( TP \), \( TP \), \( TN \) and \( FN \) indicate the number of correctly identified ARDS patients (true positive; \( TP \)), the number of non-ARDS patients who were identified as having ARDS (false positive; \( FP \)), the number of non-ARDS patients who were identified as having non-ARDS (true negative; \( TN \)) and the number of ARDS patients who were identified as having non-ARDS (false negative; \( FN \)).

Patient and public involvement

In this study, we used deidentified data from the original cohort study with no direct involvement of or interaction with participants in the design, recruitment or conduct of this study.

Results

Patient characteristics

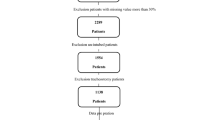

A total of 11,829 patients were admitted to the ICU, and 296 patients (203 men, 93 women; mean age, 65.40 ± 18.13 years) were included in this study. Among them, 91 (30.74%) developed ARDS. Table 1 shows the baseline characteristics and clinical/laboratory parameters in the training set. A total of 42 variables, including baseline characteristics, clinical/laboratory parameters, and predisposing conditions, were collected for each patient; many other variables with several missing values were omitted. The basic information compared between the training and validation sets is shown in Table 2. Figure 1 shows the process of cohort selection.

Key features and classification results

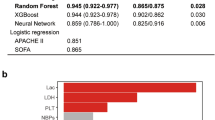

In most cases, an ensemble model with a greater number of variables will provide a more accurate prediction than a model with fewer variables. However, it is more cost-effective and efficient to obtain similar or even the same improvement by using prominent features, which can thus benefit clinical practice. Based on the fact that features built on the top of trees contribute more to predicting ARDS in at-risk patients, the relative importance of each feature is provided in Fig. 2.

Next, we performed random forest classification with the same parameters (to make the comparison possible and remove the effect of the parameters) with different subsets of features to calculate the changes in AUC values, as illustrated in Fig. 3. In this study, the AUC values of different feature combinations determined the importance of the input variables. As shown in Fig. 3, the classification error decreases as the number of features gradually increases. The AUC value remains at a similar level after the number of features increases past 11. Therefore, the following 11 features were included in the final model for the prediction of ARDS: minimum respiratory rate, maximum respiratory rate, minimum haematocrit, minimum systolic blood pressure, minimum mean arterial pressure (MAP), maximum heart rate, minimum glucose, minimum white blood cell (WBC) count, minimum heart rate, minimum temperature, and minimum sodium level. With the testing set, the final predictive model achieved an AUC of 0.87 (ROC curve illustrated in Fig. 4), an accuracy of 82%, an MCC of 0.64 and an F1 of 0.73; these results are sufficient to predict which patients will develop ARDS. To demonstrate the robustness of the predictions of the model, the final ensemble model with 11 features included 200 bootstrap replicates [19,20,21] and achieved an average AUC of 0.82 (with an average accuracy of 0.83, an average MCC of 0.50 and an average F1 of 0.57) in the testing set. The prediction results suggest that the ensemble model with 11 key features is feasible and practical.

Discussion

This study presents the first predictive model including 11 predictors for ARDS events. Specifically, the 11 predictors included the following: maximum and minimum respiratory rate and heart rate as well as minimum systolic blood pressure, MAP, temperature, WBC count and the levels of glucose, haematocrit, and sodium. Furthermore, the maximum and minimum respiratory rate and the minimum systolic blood pressure on the first day of admission were significantly associated with ARDS events. In addition, for the first time, four new biomarkers were included in the predictive model for ARDS events: decreased minimum haematocrit, glucose, and sodium levels as well as increased minimum WBC count.

Acute respiratory distress syndrome is a life-threatening inflammatory disease of the lungs [22, 23]. Although a mechanical ventilation strategy has been shown to influence mortality in this syndrome, there is currently no proven pharmacologic treatment despite more than 30 completed or ongoing clinical trials [22]. However, many studies [24,25,26,27,28] have reported different predictive models for in-hospital mortality in ARDS patients, and several studies [22, 29,30,31,32,33] have also shown that there are many predictors of mortality in ARDS patients. Terpstra et al. [12] reported 20 biomarkers for the diagnosis of ARDS and 19 biomarkers for predicting mortality in ARDS patients. In addition, some studies [34, 35] have shown that combining multiple biomarkers can enhance diagnostic accuracy. In the present study, we established a predictive model for ARDS events in ICU patients.

In our study, we selected 11 prominent predictors from 42 variables for the predictive model of ARDS events. Previous studies [36,37,38] have reported that a majority of predictors of mortality or factors involved in diagnosis in ARDS patients are inflammatory factors or lung surface proteins; however, the predictors that we selected are biochemical indicators of ARDS events. Moreover, we included four basic vital signs in the predictive model for ARDS events and found that the minimum and maximum respiratory rates were increased in critical patients with ARDS or non-ARDS compared with healthy patients and were higher in ARDS patients than in non-ARDS patients. In addition, the minimum systolic pressure and MAP were lower in critical patients with ARDS or non-ARDS than in healthy patients and lower in ARDS patients than in non-ARDS patients, which is consistent with the clinical manifestations of ARDS [39]. Furthermore, this is the first model to include four new biomarkers as predictors of ARDS events. First, the minimum glucose level was tested in our model for ARDS patients; glucose levels were higher in critical patients with ARDS or non-ARDS than in healthy people and lower in ARDS patients than non-ARDS patients. Inflammation plays a vital role in ARDS events [40], and many studies [41, 42] have shown a protective effect of hyperglycaemia against ARDS due to inhibition of the protein nuclear factor-kappa-B (NF-κB) inhibitor alpha (IκB-α) and the p56 subunit and the impairment of NF-κB activation in sepsis-induced ALI/ARDS; on the other hand, high glucose levels are associated with decreased neutrophil migration, decreased inflammatory factor secretion, and a reduced inflammatory response. Moreover, a meta-analysis [43] also reported that the risk of death was decreased in adult ARDS patients with pre-existing diabetes, supporting the protective effect of hyperglycaemia against ARDS; this finding was in line with the results of the lung injury prediction score (LIPS) [44, 45]. All of the aforementioned research supports the results of our study. Second, the minimum sodium level was within the normal range but was lower in ARDS patients than in non-ARDS patients. This result may be associated with inhibited lung epithelial sodium channels (ENaCs) in ARDS patients. Several studies [46,47,48,49,50] have reported that inflammation alters the functions of ENaC and ATPase, inhibiting the active transport of Na+ from the alveoli to the interstitium, increasing the exchange of sodium in the vasculature and lung interstitium, and ultimately reducing the sodium concentration in the vasculature. In addition, another study [51] showed that pharmacological inhibitors of lung apical Na+ channels can reduce the rate at which fluid is cleared and form a positive feedback loop with inflammation in the lung, which may also explain the results of our study. Third, the minimum WBC count was within the normal range but was higher in ARDS patients than non-ARDS patients. WBCs may be regarded as the most important effector cells involved in acute inflammation during the pathogenesis of ARDS. In the case of trauma, sepsis, acute pancreatitis, physical and chemical stimulation, or extracorporeal circulation, as a result of the effects of lipopolysaccharide, complement component 5a receptor, and IL-8, WBCs are concentrated in pulmonary capillaries. Furthermore, WBCs can adhere to endothelial cells and migrate across the endothelium and then enter the lung interstitium, which leads to WBC movement to the alveolar cavity from the alveolar epithelium. Furthermore, there are many types of adhesion molecules involved in this process. Finally, stimulated alveolar macrophages (AMS) release IL-1, TNF-α and IL-8, which promote the chemotaxis and aggregation of WBCs in the lung and may promote ALI; this finding is consistent with the fact that ARDS is associated with an inflammatory environment in the lung [52,53,54]. The evidence from the above studies is insufficient, although they provide insight into the mechanism underlying ARDS. Most importantly, some recent studies [55, 56] have developed a model of ARDS sub-phenotypes that not only reflects the developmental tendency of ARDS but also plays a decisive role in clinical treatment. Fourth, the minimum haematocrit level was within the normal range but was lower in ARDS patients than in non-ARDS patients. The mechanism underlying this result may be explained by a study [57] showing that the systemic blood flow rate per unit body surface decreases significantly from baseline following the induction of ARDS and that the haematocrit level increased as the systemic blood flow decreased, effectively increasing the systemic oxygen delivery within a certain range in ARDS patients; this process is in accordance with our study results. In sum, we believe that the biomarkers newly discovered in this study provide guidance for future interventional research on ARDS.

In addition, this secondary analysis has several limitations. First, we defined ARDS based only on the Berlin Definition, which varies from the definition of the AECC [3], which may increase the difficulty of diagnosis and the omission of some patients who developed ARDS during the study. Second, this study is a secondary analysis of data from a prospective observational study that was not recorded and indicated when the patients developed ARDS. Third, this prediction model may lack generalisability because the 42 included variables are still too few and because many other variables with too many missing values were omitted. The greater the number of included variables, the higher the predictive accuracy of this model. However, we hope that we can include more patients and variables in future prospective research. Fourth, the robustness of this study cannot be confirmed without an external validation cohort. We hope to accomplish this aim in future prospective research.

Conclusions

A model with 11 key features was successfully established for predicting ARDS events in Chinese patients. This model can be applied to predict ARDS events by using biomarkers, such as minimum WBC count and glucose, haematocrit and sodium levels. Four new biomarkers were included in this model: decreased minimum sodium concentration, haematocrit, and glucose levels and increased minimum WBC count.

Abbreviations

- ARDS:

-

acute respiratory distress syndrome

- ICUs:

-

intensive care units

- ROC:

-

receiver operating characteristic

- AUC:

-

area under the receiver operating characteristic curve

- WBC:

-

white blood cell

- ALI:

-

acute lung injury

- AECC:

-

American–European Consensus Criteria

- RAGE:

-

receptor for advanced glycation end-products

- SP-D:

-

surfactant protein D

- IL:

-

interleukin

- TNF-α:

-

tumour necrosis factor-α

- PRBCs:

-

packed red blood cells

- MCC:

-

Matthews correlation coefficient

- F1 :

-

F-measure

- TP:

-

true positive

- FP:

-

false positive

- TN:

-

true negative

- FN:

-

false negative

- MAP:

-

mean arterial pressure

- APACHE II:

-

Acute Physiology and Chronic Health Evaluation II

- NF-κB:

-

nuclear factor-kappa-B

- IκB-α:

-

inhibition of the protein nuclear factor-kappa-B inhibitor alpha

- ENaCs:

-

epithelial sodium channels

- AMS:

-

alveolar macrophages

References

Ashbaugh DG, Bigelow DB, Petty TL, Levine BE. Acute respiratory distress in adults. Lancet. 1967;2:319–23.

Tomashefski JF Jr. Pulmonary pathology of acute respiratory distress syndrome. Clin Chest Med. 2000;21:435–66.

Ranieri VM, Rubenfeld GD, Thompson BT, Ferguson ND, Caldwell E, Fan E, Camporota L, Slutsky AS. Acute respiratory distress syndrome: the Berlin definition. JAMA. 2012;307:2526–33.

Rubenfeld GD, Caldwell E, Peabody E, Weaver J, Martin DP, Neff M, Stern EJ, Hudson LD. Incidence and outcomes of acute lung injury. N Engl J Med. 2005;353:1685–93.

Villar J, Blanco J, Kacmarek RM. Current incidence and outcome of the acute respiratory distress syndrome. Curr Opin Crit Care. 2016;22:1–6.

Diaz JV, Brower R, Calfee CS, Matthay MA. Therapeutic strategies for severe acute lung injury. Crit Care Med. 2010;38:1644–50.

Biomarkers Definitions Working Group. Biomarkers and surrogate endpoints: preferred definitions and conceptual framework. Clin Pharmacol Ther. 2001;69:89–95.

Barnett N, Ware LB. Biomarkers in acute lung injury—marking forward progress. Crit Care Clin. 2011;27:661–83.

Esteban A, Fernandez-Segoviano P, Frutos-Vivar F, Aramburu JA, Najera L, Ferguson ND, Alia I, Gordo F, Rios F. Comparison of clinical criteria for the acute respiratory distress syndrome with autopsy findings. Ann Intern Med. 2004;141:440–5.

Estenssoro E, Dubin A, Laffaire E, Canales HS, Saenz G, Moseinco M, Bachetti P. Impact of positive end-expiratory pressure on the definition of acute respiratory distress syndrome. Intensive Care Med. 2003;29:1936–42.

Garcia-Laorden MI, Lorente JA, Flores C, Slutsky AS, Villar J. Biomarkers for the acute respiratory distress syndrome: how to make the diagnosis more precise. Ann Transl Med. 2017;5:283.

Terpstra ML, Aman J, van Nieuw Amerongen GP, Groeneveld AB. Plasma biomarkers for acute respiratory distress syndrome: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Crit Care Med. 2014;42:691–700.

Cross LJ, Matthay MA. Biomarkers in acute lung injury: insights into the pathogenesis of acute lung injury. Crit Care Clin. 2011;27:355–77.

Wang T, Zhu Z, Liu Z, Yi L, Yang Z, Bian W, Chen W, Wang S, Li G, Li A, et al. Plasma neutrophil elastase and elafin as prognostic biomarker for acute respiratory distress syndrome: a multicenter survival and longitudinal prospective observation study. Shock. 2017;48:168–74.

Zaklouta F, Stanciulescu B, Hamdoun O. Traffic sign classification using kd trees and random forests. In: Neural networks (IJCNN), The 2011 international joint conference on. IEEE; 2011. p. 2151–5.

Breiman L. Arcing classifiers. Ann Stat. 1996;26:123–40.

Breiman L. Random forests. Mach Learn. 2001;45:5–32.

Houk JC, Davis JL, Beiser DG. Models of information processing in the basal ganglia. Cambridge: MIT press; 1995.

Efron B, Tibshirani RJ. An introduction to the bootstrap. Boca Raton: CRC Press; 1994.

Slonim DK. From patterns to pathways: gene expression data analysis comes of age. Nat Genet. 2002;32:502.

Wang L. Support vector machines: theory and applications. Berlin: Springer Science & Business Media; 2005.

Zhu Z, Liang L, Zhang R, Wei Y, Su L, Tejera P, Guo Y, Wang Z, Lu Q, Baccarelli AA, et al. Whole blood microRNA markers are associated with acute respiratory distress syndrome. Intensive Care Med Exp. 2017;5:38.

Xie H, Zhou ZG, Jin W, Yuan CB, Du J, Lu J, Wang RL. Ventilator management for acute respiratory distress syndrome associated with avian influenza A (H7N9) virus infection: a case series. World J Emerg Med. 2018;9:118–24.

Zhao Z, Wickersham N, Kangelaris KN, May AK, Bernard GR, Matthay MA, Calfee CS, Koyama T, Ware LB. External validation of a biomarker and clinical prediction model for hospital mortality in acute respiratory distress syndrome. Intensive Care Med. 2017;43:1123–31.

Zhang Z, Ni H. Prediction model for critically ill patients with acute respiratory distress syndrome. PLoS ONE. 2015;10:e0120641.

Villar J, Perez-Mendez L, Basaldua S, Blanco J, Aguilar G, Toral D, Zavala E, Romera MA, Gonzalez-Diaz G, Nogal FD, et al. A risk tertiles model for predicting mortality in patients with acute respiratory distress syndrome: age, plateau pressure, and P(aO(2))/F(IO(2)) at ARDS onset can predict mortality. Respir Care. 2011;56:420–8.

Damluji A, Colantuoni E, Mendez-Tellez PA, Sevransky JE, Fan E, Shanholtz C, Wojnar M, Pronovost PJ, Needham DM. Short-term mortality prediction for acute lung injury patients: external validation of the Acute Respiratory Distress Syndrome Network prediction model. Crit Care Med. 2011;39:1023–8.

Bauman ZM, Gassner MY, Coughlin MA, Mahan M, Watras J. Lung injury prediction score is useful in predicting acute respiratory distress syndrome and mortality in surgical critical care patients. Crit Care Res Pract. 2015;2015:157408.

Yehya N, Wong HR. Adaptation of a biomarker-based sepsis mortality risk stratification tool for pediatric acute respiratory distress syndrome. Crit Care Med. 2018;46:e9–16.

Cartin-Ceba R, Hubmayr RD, Qin R, Peters S, Determann RM, Schultz MJ, Gajic O. Predictive value of plasma biomarkers for mortality and organ failure development in patients with acute respiratory distress syndrome. J Crit Care. 2015;30:219.e211–7.

Menk M, Giebelhauser L, Vorderwulbecke G, Gassner M, Graw JA, Weiss B, Zimmermann M, Wernecke KD, Weber-Carstens S. Nucleated red blood cells as predictors of mortality in patients with acute respiratory distress syndrome (ARDS): an observational study. Ann Intensive Care. 2018;8:42.

Okajima K, Harada N, Sakurai G, Soga Y, Suga H, Terada T, Nakagawa T. Rapid assay for plasma soluble E-selectin predicts the development of acute respiratory distress syndrome in patients with systemic inflammatory response syndrome. Transl Res. 2006;148:295–300.

Geboers DG, de Beer FM, Tuip-de Boer AM, van der Poll T, Horn J, Cremer OL, Bonten MJ, Ong DS, Schultz MJ, Bos LD. Plasma suPAR as a prognostic biological marker for ICU mortality in ARDS patients. Intensive Care Med. 2015;41:1281–90.

Parsons PE, Eisner MD, Thompson BT, Matthay MA, Ancukiewicz M, Bernard GR, Wheeler AP. Lower tidal volume ventilation and plasma cytokine markers of inflammation in patients with acute lung injury. Crit Care Med. 2005;33:1–6 (discussion 230–232).

Calfee CS, Ware LB, Glidden DV, Eisner MD, Parsons PE, Thompson BT, Matthay MA. Use of risk reclassification with multiple biomarkers improves mortality prediction in acute lung injury. Crit Care Med. 2011;39:711–7.

Wang Z, Beach D, Su L, Zhai R, Christiani DC. A genome-wide expression analysis in blood identifies pre-elafin as a biomarker in ARDS. Am J Respir Cell Mol Biol. 2008;38:724–32.

Fremont RD, Koyama T, Calfee CS, Wu W, Dossett LA, Bossert FR, Mitchell D, Wickersham N, Bernard GR, Matthay MA, et al. Acute lung injury in patients with traumatic injuries: utility of a panel of biomarkers for diagnosis and pathogenesis. J Trauma. 2010;68:1121–7.

Ware LB, Koyama T, Zhao Z, Janz DR, Wickersham N, Bernard GR, May AK, Calfee CS, Matthay MA. Biomarkers of lung epithelial injury and inflammation distinguish severe sepsis patients with acute respiratory distress syndrome. Crit Care. 2013;17:R253.

Fan E, Brodie D, Slutsky AS. Acute respiratory distress syndrome: advances in diagnosis and treatment. JAMA. 2018;319:698–710.

Kollef MH, Schuster DP. The acute respiratory distress syndrome. N Engl J Med. 1995;332:27–37.

Filgueiras LR Jr, Martins JO, Serezani CH, Capelozzi VL, Montes MB, Jancar S. Sepsis-induced acute lung injury (ALI) is milder in diabetic rats and correlates with impaired NFkB activation. PLoS ONE. 2012;7:e44987.

Spiller F, Carlos D, Souto FO, de Freitas A, Soares FS, Vieira SM, Paula FJ, Alves-Filho JC, Cunha FQ. alpha1-Acid glycoprotein decreases neutrophil migration and increases susceptibility to sepsis in diabetic mice. Diabetes. 2012;61:1584–91.

Gu WJ, Wan YD, Tie HT, Kan QC, Sun TW. Risk of acute lung injury/acute respiratory distress syndrome in critically ill adult patients with pre-existing diabetes: a meta-analysis. PLoS ONE. 2014;9:e90426.

Gajic O, Dabbagh O, Park PK, Adesanya A, Chang SY, Hou P, Anderson H 3rd, Hoth JJ, Mikkelsen ME, Gentile NT, et al. Early identification of patients at risk of acute lung injury: evaluation of lung injury prediction score in a multicenter cohort study. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2011;183:462–70.

Trillo-Alvarez C, Cartin-Ceba R, Kor DJ, Kojicic M, Kashyap R, Thakur S, Thakur L, Herasevich V, Malinchoc M, Gajic O. Acute lung injury prediction score: derivation and validation in a population-based sample. Eur Respir J. 2011;37:604–9.

Adir Y, Welch LC, Dumasius V, Factor P, Sznajder JI, Ridge KM. Overexpression of the Na-K-ATPase alpha2-subunit improves lung liquid clearance during ventilation-induced lung injury. Am J Physiol Lung Cell Mol Physiol. 2008;294:L1233–7.

Comellas AP, Kelly AM, Trejo HE, Briva A, Lee J, Sznajder JI, Dada LA. Insulin regulates alveolar epithelial function by inducing Na+/K+-ATPase translocation to the plasma membrane in a process mediated by the action of Akt. J Cell Sci. 2010;123:1343–51.

Gusarova GA, Trejo HE, Dada LA, Briva A, Welch LC, Hamanaka RB, Mutlu GM, Chandel NS, Prakriya M, Sznajder JI. Hypoxia leads to Na, K-ATPase downregulation via Ca(2+) release-activated Ca(2+) channels and AMPK activation. Mol Cell Biol. 2011;31:3546–56.

Lecuona E, Sun H, Chen J, Trejo HE, Baker MA, Sznajder JI. Protein kinase A-Ialpha regulates Na, K-ATPase endocytosis in alveolar epithelial cells exposed to high CO(2) concentrations. Am J Respir Cell Mol Biol. 2013;48:626–34.

Lecuona E, Trejo HE, Sznajder JI. Regulation of Na, K-ATPase during acute lung injury. J Bioenerg Biomembr. 2007;39:391–5.

Wynne BM, Zou L, Linck V, Hoover RS, Ma HP, Eaton DC. Regulation of lung epithelial sodium channels by cytokines and chemokines. Front Immunol. 2017;8:766.

Thille AW, Esteban A, Fernandez-Segoviano P, Rodriguez JM, Aramburu JA, Penuelas O, Cortes-Puch I, Cardinal-Fernandez P, Lorente JA, Frutos-Vivar F. Comparison of the Berlin definition for acute respiratory distress syndrome with autopsy. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2013;187:761–7.

Burnham EL, Janssen WJ, Riches DW, Moss M, Downey GP. The fibroproliferative response in acute respiratory distress syndrome: mechanisms and clinical significance. Eur Respir J. 2014;43:276–85.

Gregoire M, Uhel F, Lesouhaitier M, Gacouin A. Impaired efferocytosis and neutrophil extracellular traps clearance by macrophages in ARDS. Eur Respir J. 2018;52:1702590.

Calfee CS, Delucchi K, Parsons PE, Thompson BT, Ware LB, Matthay MA. Subphenotypes in acute respiratory distress syndrome: latent class analysis of data from two randomised controlled trials. Lancet Respir Med. 2014;2:611–20.

Famous KR, Delucchi K, Ware LB, Kangelaris KN, Liu KD, Thompson BT, Calfee CS. Acute respiratory distress syndrome subphenotypes respond differently to randomized fluid management strategy. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2017;195:331–8.

Marini CP, Russo GC, Nathan IM, Jurkiewicz A, McNelis J. Effect of hematocrit on regional oxygen delivery and extraction in an adult respiratory distress syndrome animal model. Am J Surg. 2000;180:108–14.

Acknowledgements

We are grateful to all the participants in the original prospective study for their contributions and the Critical Care Medicine Professional Committee of the Chinese Research Hospital Association for providing some guidance regarding our manuscript.

Funding

This study was supported by the Capital Medical Development Research Fund China (No. 2009-1014), National Natural Science Foundation China (No. 81372043), Beijing Natural Science Foundation (No. 7162199), Natural Science Foundation of Henan Province (Grant No. 182300410369), Science and Technology Innovation Talents in Universities of Henan Province (16IRTSTHN021), and National Science and Technology Major Project (2018ZX10101004).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

XZ and T-WS had full access to all of the data in the study and take responsibility for the integrity of the data, the accuracy of the data analysis, and the administrative, technical, or material support; XZ, T-WS, X-FD and Z-YW contributed to the study concept and design; Z-YW, ZL, LY, W-SB and S-PW contributed to the acquisition of data; X-FD, J-BL, H-YL and T-TJ contributed to the drafting of the manuscript. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Corresponding authors

Ethics declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate

Not applicable.

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/), which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made. The Creative Commons Public Domain Dedication waiver (http://creativecommons.org/publicdomain/zero/1.0/) applies to the data made available in this article, unless otherwise stated.

About this article

Cite this article

Ding, XF., Li, JB., Liang, HY. et al. Predictive model for acute respiratory distress syndrome events in ICU patients in China using machine learning algorithms: a secondary analysis of a cohort study. J Transl Med 17, 326 (2019). https://doi.org/10.1186/s12967-019-2075-0

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/s12967-019-2075-0