Abstract

Background

National food environment policies can contribute to the reduction of diet-related non-communicable diseases. Yet, their implementation in the Netherlands remains low. It has been hypothesized that the media can play a pivotal role in inducing spikes in policy attention, thereby shaping political action. The aim of this study was to examine the discourse on food policies in Dutch newspaper articles between 2000–2022, by analyzing arguments used by various actors.

Methods

A systematic search in Nexis Uni was used to identify newspaper articles that covered national-level Dutch food environment policies published in seven Dutch national newspapers between 2000–2022. Covered policies were classified into six domains including food composition, labeling, promotion, prices, provision and retail and into the four stages of the policy cycle; policy formulation, decision-making, implementation, and evaluation. A grey literature search was used to identify food policies implemented during 2000–2022. Descriptive statistics were used to summarize coverage of policies over time, policy type and policy stage. An interpretive content analysis was performed on a random subsample of the newspaper articles to determine the actors, viewpoints and arguments of the food policies.

Results

We identified 896 relevant newspaper articles. The coverage of food policies in newspapers was initially low but peaked in 2018/2021/2022. Through grey literature search we identified 6 food policies which were implemented or adjusted between 2000–2022. The majority of the newspaper articles reported on food pricing policies and were discussed in the policy formulation stage. Academics (mainly supportive) were the most and food industry (mostly opposing) the least cited actors. Supportive arguments highlighted health consequences, health inequalities and collective responsibility, whereas opposing arguments focused on unwanted governmental interference and ineffectiveness of policies.

Conclusions

Dutch newspaper articles covering food policies represented a variety of actors and arguments, with individual versus collective responsibility for food choices playing a central role in the arguments. These insights may serve as a basis for further research into why certain arguments are used and their effect on policy attention and implementation.

Similar content being viewed by others

Background

Globally, non-communicable diseases (NCDs) are the leading cause of death [1]. An unhealthy diet is the largest risk factor for NCDs, surpassing smoking [2]. Regulatory and policy measures that target the unhealthy food environment such as a sugar-sweetened beverages (SBB) tax can contribute to the reduction of diet-related NCDs [3,4,5,6,7]. These national food environment policies (hereafter referred to as food policies) are strongly advised by globally recognized expert organizations such as the United Nations, the World Health Organization, and the Task Force on Fiscal Policy for Health [8,9,10,11,12]. Yet, there is a wide variation between countries in the extent to which such food policies are implemented, with the Netherlands ranked as the second lowest country compared to eleven European countries [13,14,15]. In 2018, the Dutch National Prevention Agreements was launched, where a range of actors agreed on measures to reduce overweight (and smoking and problematic alcohol use). In response to this launch, academics and the National Institute for Public Health and the Environment argued that with these agreements, targets to reduce overweight would not be met and that additional policies would be necessary [16, 17]. Currently, there are no unhealthy food taxes, national restrictions on marketing of unhealthy foods, no subsidies on fruit and vegetables and no regulations on food placement and promotion in the Netherlands, although the Nutri-Score label was adopted as a voluntary front-of-pack label since 2024..

The process of food policy adoption and implementation is complex and depends on several interacting factors, including the perceived severity of the health problem, generation and interpretation of scientific evidence for effectiveness of food policies, industry group activities, and the political and public attitude towards food policies [18,19,20,21,22,23]. While politicians have the power to implement and change food policies, they often favor the status quo [24]. Political stability predominates, with substantial policy changes only occasionally emerging when new ideas manage to break through [24, 25]. This phenomenon is also described in the punctuated equilibrium theory, which states that there is political stability most of the time, but sometimes there is a spike in policy changes [25].

One of the factors that can play an important role in inducing spikes in policy changes and thereby shape political action is the media [26,27,28,29,30,31,32,33]. Media outlets such as (online) newspapers, radio and television determine what and who gets a platform, and as such, influence which issues rise or fall on the public agenda. Media outlets, and especially actors using media, can select, emphasize or omit specific aspects of the topic to shape the understanding of the covered topic (i.e., framing). Consequently, the framing of an issue of food policy may influence the collective attitude in society towards this issue [34,35,36,37,38]. Media attention occurs during all stages of the policy cycle by describing suggested food policies (agenda-setting and policy formulation), expressing preferences (decision-making), reporting on implementation progress (implementation) and reporting on impact (evaluation) [33, 39].

What actors are represented in newspapers and which viewpoints and arguments they propagate may play an important role in understanding the framing of food policies in the media, but a limited number of studies have investigated this. In the case of the Soft Drinks Industry Levy in the UK, public health advocates – who were in favor of the policy—were most prominently represented [40]. Australian researchers found that although newspaper coverage of food policies was low, the majority of the food policy issues covered in newspapers were positively displayed in terms of public health [41]. Regarding the arguments in the newspaper articles, UK researchers identified various arguments, including appropriateness of regulation, (lack of) evidence, consequences of implementation, legal issues and social responsibility [40]. This latter argument is in line with Beauchamp (1976) and was also identified by a German study [42, 43]. German researchers found that in the case of the sugar tax, the focus in newspapers was mainly on societal responsibility which was centered around the debate of binding measures and voluntary solutions by the food industry [43]. In addition, Australian researchers observed that arguments that were in favor of food policies tended to be framed in terms of public health or society benefits, whereas dismissive arguments tended to be framed in economic, practical or ideological terms [44].

To understand the potential links between newspaper coverage and food policy adoption and implementation in the Netherlands, we first need to get a comprehensive overview of the coverage of different food policies, the policy cycle phase to which they correspond and actors' views and arguments regarding food policy issues in Dutch newspapers. We aimed to examine the discourse on food policies in Dutch newspaper articles between 2000–2022 by analyzing arguments used by various actors.

Methods

Study design

We conducted a systematic document analysis as part of a historical qualitative study design. We chose newsprint media in line with Cicchini et al. [41], as this is a consistent and substantial news source [41]. Additionally, in line with Cicchini et al. [41], we selected approximately 20 years to cover a relatively long historical period [41]. We followed the Standards for Reporting Qualitative Research (SRQR) and the checklist including a detailed description of our methods can be found in the Supplementary materials [45].

Data collection

To identify relevant publications, we conducted a systematic search in Nexis Uni (LexisNexis) from inception up to December 31, 2022, in collaboration with a medical information specialist of the university library. We included all national newspapers in the Netherlands in 2022 (Algemeen Dagblad, Nederlands Dagblad, NRC (Handelsblad & in de ochtend), Reformatorisch Dagblad, de Telegraaf, Trouw, de Volkskrant) except for Manifest as this is a very small newspaper [46]. Het Financieele Dagblad was not available in Nexis Uni and therefore excluded.

Based on a literature study and discussion among the research team, we searched for terms related to national-level Dutch food policies. Examples of search terms are: sugar-sweetened beverages tax, food choice logo, healthy canteen, food retail, food promotion ban, food/meal composition, reduce sugar/saturated fat/trans-fat/salt(see Supplementary Table 1 for the complete search strategy).

Two assessors (NMSD and NS) independently screened titles and full texts of newspapers for eligibility. A 10% random sample of all identified newspaper articles was assessed by a third, independent assessor (JDM). We resolved differences in judgment through a consensus procedure. To be included, newspaper articles had to (a) be published in Dutch; (b) be published between the years 2000 and 2022; and (c) report on a (proposed) compulsory national-level Dutch food policy, thereby excluding self-regulatory or non-binding agreements.

We used the Dutch descriptions of food policy classifications from Djojosoeparto et al., [15], which was derived from Swinburn et al., [47], to categorize food policies into domains [15, 47]. These domains included food composition (e.g., reformulation policies to improve the nutrient profile), food labeling (e.g., legislating front-of-pack label), food promotion (e.g., marketing ban), food prices (e.g., sugar tax), food provision (e.g., nutritional standards for healthy school canteens) and food in retail (e.g., zoning policies for fast food) (see Supplementary Methods section including Supplementary Table 2) [15]. In line with Cicchini et. al. (2022), we excluded the domain of food trade and investments because of the focus on national policies, as the domain food trade and investments are part of global commerce [41]. We considered policies regarding all foods and beverages. We chose to include breastfeeding policies as research suggests that breastfeeding may protect against non-communicable diseases [48]. We excluded newspaper articles about alcohol as this is mostly not studied as food but as a different subgroup [49,50,51].

We used the policy cycle from Jann & Wegrich [39] to determine the specific stage within the cycle to which the identified food policy was associated [39]. The described policy stages are categorized as agenda-setting (e.g., problem recognition and issue selection), policy formulation (e.g., suggestion possible policies), decision-making (e.g., decision to implement (or abolish) policy), implementation (e.g., implementation / abolishment process), and evaluation (e.g., effect policy) (see Supplementary Methods section) [39]. As the agenda-setting phase is explained as problem recognition and issue selection without the formulation of a policy which could counter this issue, the stage agenda-setting could not be assessed. A grey literature search was done to retrieve implemented food policies in the Netherlands between 2000–2022. We started with the overview of governmental food policies from the Food-EPI project in the Netherlands [15]. To find additional implemented policies, different governmental websites were used as a starting point, such as wetten.overheid.nl, rijksoverheid.nl, belastingdienst.nl, and voedingscentrum.nl. Additionally, we performed unsystematic Internet searchers for further information about implemented food policies. Based on Hilton et al., [40] and discussions among the research team, we made a classification of actor groups [40]. These actors included academics, consumers, policymakers, actors working in public health/ environmental organizations and actors working in the food industry (see Supplementary Methods section and Supplementary Table 3). If no information regarding an actor was available, we coded this as 'unknown'. Identified individuals and/or organizations in newspaper articles were considered to be actors when direct quotes were supplied in the articles or when individuals and/or organizations were mentioned in relation to the policy and their viewpoint was considered verifiable. We categorized the viewpoints of actors as 'supportive', 'opposed' or 'neutral' towards the food policy based on the described arguments in the newspaper article.

Data analysis

One assessor (NMSD or NS) extracted details from all newspaper articles, including year of publication, covered food policy issues and the stage of the policy cycle, and these details were entered in Microsoft Excel for descriptive statistical purposes (Fig. 1).

From a random subsample, represented actors, viewpoints and arguments were identified (by ND) (Fig. 1). Randomly sorted newspaper articles were analyzed until no new or remarkable ratio of actors and represented arguments appeared, thus data saturation was reached. As newspaper articles could include multiple food policy issues, actors, viewpoints and arguments, newspaper articles were coded independently per food policy issue. Therefore, we coded until saturation was met per food policy domain. This resulted in coding of around a 20% random sample of the newspaper articles regarding food prices and around a 40% random sample of the newspaper articles covering other domains. We used a combination of deductive and inductive coding in the software program ATLAS.ti 23. We used deductive coding for the actors in the newspaper articles and the viewpoints and arguments of actors regarding the food policy issue through interpretive content analysis. In line with Rowbotham et al. [44] we initially deductively coded arguments into the themes of health, societal, economic, practical and cultural/ideological (see Supplementary Methods section and Supplementary Table 4) [44]. If arguments did not fit in these themes, we used inductive coding, which led to the formulation of additional themes based on the content analysis. If there was no clear argumentation, we labeled these articles as having ‘no argumentation’. Based on Hilton et al., [40],Rowbotham et al., [44] and discussion among the research team, we set up pilot arguments for each viewpoint and theme to clarify what type of arguments would fall under what themes (see Supplementary Methods section) [40, 44]. For instance, there were arguments regarding the need for government policies because it is the government’s responsibility to protect citizens (cultural/ideological argument) and regarding the need for government policies because they would have an effect on health that other solutions do not have (health argument). A 10% random sample of the analyzed subsample was coded by a second, independent assessor (NS). We resolved differences in judgment through a consensus procedure.

Results

The literature search generated a total of 4632 references (see Fig. 1). After removing duplicates, 4347 references remained. In total, 896 articles satisfied the inclusion criteria. Articles were removed because no compulsory national-level Dutch food policy was covered or articles were not newspaper articles (e.g., puzzles, tv-program explanations and recipes.).

Volume and content in Dutch newspapers

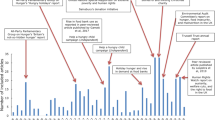

In the 896 included newspaper articles, food policies were mentioned 1464 times. The prevalence of food policy coverage in newspaper articles was low in the early 2000s and fluctuated until 2017 (Fig. 2). From 2018 on, the prevalence of food policy coverage increased, with peaks in 2018, 2021 and 2022. Regarding the content of newspaper articles, the majority (73,6%) of the newspaper articles reported on food price policies (Fig. 2). These articles mainly discussed meat, sugar, and fruit/vegetable taxation. Other food policy domains were mentioned less often (ranging from food composition (3,2%) to food labeling (7,5%)) (see Supplementary Table 5). The different food policy domains were roughly covered equally between newspapers (see Supplementary Fig. 1). Newspaper articles mainly described food policies in the stage of policy formulation (94,2%) (see Supplementary Table 6). Other stages of the policy cycle were discussed less frequently in the newspapers (ranging from implementation (0,1%) to decision-making (4,9%)). Through grey literature search we identified 6 food policies which were implemented or adjusted between 2000–2022 (arrows in Fig. 2).

-

Policy 1: 2007: Commodities act degree on flour and bread: maximum salt content in bread reduced from 2.5% to 2.1% [52]

-

Policy 2: 2007: Commodities act degree on meat, minced meat and meat products: maximum fat content in minced meat reduced from 35 to 25% [53]

-

Policy 3: 2013: The maximum content of salt in bread went reduced from 2.1% to 1.8% [52].

-

Policy 4: 2014 & 2015: Law on the consumption tax of alcohol-free drinks; 2014 the consumption tax went from €4,13 to €5,70 per hectoliter for fruit juice, vegetable juice, and mineral water. For lemonade the tax went from €5,50 to €7,79 per hectoliter. 2015; the consumption tax for all alcohol-free drinks went to €8,83 per hectoliter [54].

-

Policy 5: 2017: Commodities act degree on preserved fruit products: minimal sugar content of jam reduced from 60 to 50% [55].

-

Policy 6: 2018, The last ‘implemented’ policy was in fact an abolishment of an existing policy, namely the food choice logo ‘Vinkje’ [15].

Frequency of national-level Dutch food policies cited in Dutch newspaper articles between 2000–2022. *Frequency is the number of times per year that a food policy was cited in the newspaper articles. *Arrows represent the timing of food policies implemented or adjusted in the Netherlands. Policy 1 = commodities act degree on four and bread; Policy 2 = commodities act degree on meat, minced meat and meat products; Policy 3 = maximum content of salt in bread; Policy 4 = law on consumption tax of alcohol-free drinks; Policy 5 = commodities act degree on preserved fruit products; Policy 6 = food choice logo

The coverage of the six implemented policies in the newspapers was limited. Only the fat reduction in minced meat, the reduction of salt in bread and the abolishment of the food choice logo ‘Vinkje’ were mentioned in a few articles. The other implemented policies were not mentioned in the newspaper articles.

Actors and their viewpoints

In the random analyzed subsample of newspaper articles, consumers (34,6%) and academics (26,2%) were most frequently represented, followed by policymakers (21,6%), public health/environmental professionals (12,9%) and actors from the food industry (4,8%). A total of 1195 unique arguments were identified (see Supplementary Table 7). Consumers (66,1%), academics (84,7%), policymakers (59,3%) and public health/environmental professionals (90,9%) were mainly supportive of the food policies across all food domains (see Supplementary Table 8). Actors from the food industry (73,7%) predominantly opposed the food policies. The frequency of different themes used by actors can be found in Fig. 3. In general, a neutral viewpoint was rarely identified for all actors. There was no clear temporal pattern in representation of actors over time. Some arguments (e.g., human health, cultural/ideological) have been mentioned in newspapers since 2000, while others (e.g., planetary health, animal welfare) only emerged after 2010 (see Fig. 4). However, the ratio between supportive and opposing arguments did not change over time.

Themes of arguments

In the random analyzed subsample of newspaper articles, we identified the themes of cultural/ideological (31.0%) and human health (30.8%) as the most prominent, followed by practical (11.4%), societal (7.8%) and economic (5.2%) themes, covering arguments in support of or opposing to the described food policies in the newspaper articles (see also Supplementary Table 9). In addition, we identified two new themes, including planetary health (6.8%) and animal welfare (0.8%). No argumentation was provided in 6.2% of the included newspaper articles.

Cultural/ideological

Cultural/ideological arguments were prevalent for both supporting and opposing the food policies of concern. Despite different food policies and actors, most identified arguments were very similar. Those in favor of the food policy (often academics and consumers) predominantly argued that current policies put too much emphasis on individual responsibility for food choices. Supporters argue that consumers, and especially children, do not truly have a ‘free choice’, and thus responsibility, in an obesogenic and unhealthy food environment (Quote 1–4, in Table 1). It was argued that governmental policies would ensure that responsibility for food choices was shifted more from the individual to a collective responsibility. These arguments were most frequently used for food retail and pricing policies. Opponents of the food policy (often policymakers, consumers and actors from the food industry) mainly argued generically that government interference is unwanted, or that the responsibility for food choices should lie with other entities such as individuals, parents, schools, food industry (Quote 8–10). Specifically for food promotion and provision policies, academics, consumers and public health professionals were often in favor of the proposed policies if they were aimed at children. However, if not aimed at children, arguments of consumers turned to unwanted government interference and displaced responsibility.

Human health

Human health arguments were also often prevalent for both supporting and opposing viewpoints regarding food policies. However, the identified arguments focused on different aspects of health. Supporters (most often academics and consumers) highlighted the current overconsumption of unhealthy foods (e.g., high in sugar, saturated fat or red/processed meat), and its linkage to possible negative health consequences (e.g., high prevalence of and increased risks for overweight, obesity, non-communicable diseases) (Quote 13). Furthermore, the supportive arguments also described the effectiveness, along with supporting evidence, of policies (in)directly decreasing obesity and negative health consequences (Quote 14). However, academics questioned the positive impact of food labeling policies on health outcomes (Quote 16). Although actors from the food industry mostly emphasized the lack of evidence regarding the impact of food policies on health, in the case of food labeling policies they argued the potential positive effect on health. Yet, food industry actors generally opposed a ban on food promotion as they argued a lack of positive impact on health.

Practical

Practical arguments included arguments such as the expected general impact and feasibility of the proposed food policy. In general, opposing arguments tended to be centered around practical issues of the development/implementation of the food policy, which were very specific per food policy. Academics and consumers argued a minimal anticipated impact of food labeling policies, citing flaws of the policy or pointing to past (unsuccessful) attempts as evidence (Quote 21). Furthermore, the feasibility of food pricing policies through European legislation or IT problems were often brought up by policymakers (Quote 23,24). In addition, actors from the food industry were prominent in arguing that the food promotion policies were practically not necessary because self-regulation (of the food industry) was sufficient (Quote 25). Exceptions were supportive arguments highlighting the effectiveness of government policies on health in general, which was mostly done by academics and consumers (Quote 17,18).

Societal

Societal arguments predominantly highlighted the anticipated positive impact of the proposed food policy on vulnerable people. However, these vulnerable groups differed per food domain. Societal arguments were mostly used for food pricing, promotion and retail policies. Academics, consumers and policymakers highlighted the need for food retail policies as the health of children would be at stake. Academics and consumers also argued the need for food promotion policies, however specific arguments from policymakers were not identified. For food pricing policies, academics, consumers and policymakers mainly highlighted the positive impact on the health of individuals with a lower socioeconomic position (Quote 26). Occasionally policymakers used ‘widening health inequalities’ as an argument opposing pricing policies (Quote 27).

Planetary health

Planetary health arguments highlighted the expected impact on the planet by the proposed food policy, which was almost exclusively used for arguments supporting a meat tax. Policymakers and environmental organizations’ professionals mostly highlighted the current global or national situation regarding climate, sustainability and/or biodiversity or focused on the effectiveness (and evidence) of the policy by (in)directly contributing to a positive impact on the planet (Quote 28,29).

Economic

Economic arguments predominantly highlighted the expected positive economic impact of the proposed food policy. Academics often stated the current situation regarding rising health care costs (that would decline due to the policies) or mentioned that possible revenues of particular food policies (e.g., sugar tax) could be used to lower the prices of healthy foods like fruit/vegetables (Quote 33,34). However, policymakers mainly discussed adverse economic consequences, particularly resulting from price policies, emphasizing issues as inflation and negative impacts on the retail market (Quote 35,36).

Animal welfare

Animal welfare arguments solely highlighted the positive expected impact on animal welfare by the proposed food policy, which was only used in the context of the meat tax (Quote 37). This was mainly done by academics and consumers. Newspaper articles never exclusively focused on animal welfare arguments but always in combination with arguments around planetary health.

Discussion

We demonstrated that between 2000–2017 the coverage of food policies in Dutch newspapers was relatively low, but increased from 2018. The majority of the newspaper articles reporting on food policies were regarding food prices and described in the stage of policy formulation. Consumers’ and academics’ viewpoints were most often reflected and they were mostly supportive of the food policies. Viewpoints from actors working in the food industry actors were least reflected and mostly opposed the food policies. Arguments in favor of food policies tended to be centered around human health (e.g., prevention), ideological (e.g., collective responsibility) or societal (e.g., reducing health inequalities) arguments, whereas opposing arguments tended to be centered around ideological (e.g., paternalism), practical (e.g., infeasibility) or human health (e.g., ineffectiveness) arguments.

The temporal patterns of food policy coverage in newspaper articles are difficult to compare, as the only comparable study in Australia shows a different pattern. Therefore, these patterns are likely to be context-dependent. The Australian study showed a pattern with peaks in 2006, 2011 and 2017–2019 [41]. In the Netherlands, the steep increase in food policy coverage around 2018 may be linked to the Dutch National Prevention Agreement that was launched in 2018 [56], which also explains why most articles focus on the policy formulation stage. In this agreement, a range of actors agreed on measures to reduce overweight (and smoking and problematic alcohol use). In response to this launch, academics and the National Institute for Public Health and the Environment argued that with these agreements, targets to reduce overweight would not be met and that additional policies would be necessary [16, 17]. This may have pushed these actors to seek press attention for additional policies such as a sugar tax. The two new themes identified as compared to an Australian study [44], planetary health and animal welfare, may also be attributable to increased awareness of global warming in the past years.

Our observations that academics were the most and food industry actors the least cited actors in newspaper articles are consistent with findings from the UK [40]. Firstly, given the low rates of food policy implementation in the Netherlands, those supporting food policy implementation are more inclined to seek media attention than those opposing food policy implementation because no media attention is likely supportive of maintaining the status quo. However, it could also be that journalists more often seek for academics’ views. Also, food industry actors may have deliberately opted to not be represented in newspaper articles as a tactical strategy to maintain a low profile in the public discourse since they may have other, less visible lobbying strategies to influence policy processes [57]. Academics may have less ability to voice their viewpoint through such quiet lobbying strategies, and newspaper media coverage is then an important strategy to share scientific insights and exercise their discursive power to reach the public.

However, not only frequency of representation but also arguments used may be indicative of actors’ discursive power. In line with Beauchamp (1976), we found that individual versus collective responsibility for food choices played an important role in Dutch newspaper articles [42]. This was also identified in a German study regarding newspaper coverage of the sugar tax [43]. Supporters argued that current policies put too much emphasis on individual responsibility, while individuals (consumers and especially children) do not truly have a ‘free choice’ and thus responsibility in an unhealthy and obesogenic food environment. Opponents argued that the government should not interfere in individual choices, thus deeming most food policies inappropriate and unjustifiable. Previous evidence suggests that unhealthy commodity industries (e.g., ultra processed food) have effectively pushed the narrative around diet and food choices towards individual responsibility [58]. As Michielsen (2022) argued around the topic of meat consumption [59], it appears that opponents tend to be more disapproving of government interference in general rather than of food specific policies. Indeed, supporters made use of substantive ideological arguments regarding food policies whereas for opponents these arguments were lacking. Furthermore, we found that opposing arguments relied on either the ineffectiveness of governmental policies to curb the health problem or the infeasibility of implementing the food policy. This is in line The Corporate Political Activity Model which highlights different strategies from unhealthy commodity industries to stop governments and global organizations from adopting effective public health policies [60]. For instance in an UK study, researchers also found that unhealthy commodity industries aimed to influence the view of the public and politicians regarding health issues by propagating arguments involving the complexity of these issues, indicating ineffectiveness of governmental policies [61]. We observed that where supporters tended to focus on the health problems/consequences, opponents rarely minimized these health problems/consequences, but focused on questions around the effectiveness of policies on these health problems/consequences. If in legislative arenas arguments of supporters and opponents also misalign, this may partly account for the lack of progress in the implementation of food policies.

In this study, we found that if economic arguments were used, these were almost exclusively in favor of implementation of food policies. In contrast, a UK study found economic arguments to be used both for supporting and opposing policies [44]. One explanation may be that this UK study included newspaper articles up until 2016. Since then, real-world evidence has countered a number of economic arguments such as the loss of jobs and profits following food policy implementation [62,63,64]. For instance, the Chilean food policy package did not have a negative impact on labor outcomes [62].

Strengths and limitations

Strengths of this study were the 22-year timeframe, detailed content analysis, coverage of volume and content of newspapers as well as various food policies, actors and arguments. This study also has limitations. Despite our extensive search strategy, we may have missed important search terms, e.g., those used during the early 2000s. Furthermore, we excluded food trade, food investment and self-regulation of the food industry which could have led to different viewpoints and arguments. In addition, we chose newspaper media, in line with previous research, as this has been a consistent and substantial media outlet for the past two decades. Yet, by exclusively focusing on newspaper articles a selection of arguments and actors was analyzed. Lastly, by grouping actors into main categories, the general result could have lost nuance as within actor groups different viewpoints and interests can be held.

Implications for practice and research

The findings from this study have implications for practice and research. Firstly, for practice, our results provide public health advocates with a clear overview of arguments used by opponents that they can try to refute. For instance, the rejection of government interference in general may be counteracted through arguments around the legal responsibility of governments to protect their citizens from harmful influences [65,66,67]. As UK researchers suggested, public health advocates could shift their focus articulating policies towards ‘empowerment of the public’ rather than propagating arguments around restricting certain consumer behaviours [68]. The findings from this study also have implications for future research. As the punctuated equilibrium theory describes, most of the time there is political stability, but sometimes there is a spike in policy changes [25]. One of the factors that can play an important role in inducing spikes in policy changes and thereby potentially shape political action is the media. Future research should determine if the increasing newspaper coverage, mainly of policies in a policy formulation stage, is an indicator for increased food policy adoption and implementation. One potential analytical approach for this could be the Granger causality test that investigates whether time series in the exposure can correctly predict time series in the outcome [69]. Secondly, future research could explore how actors’ viewpoints and arguments change over time and between types of newspapers. This could provide a further understanding of when and why certain arguments are abandoned over time, and which arguments remain as they may considered effective. Finally, we were unable to identify the quality of argumentation, i.e., distinguishing between facts, opinions and myths, as there is no valid methodology yet to do so. Considering the rising infodemic, more attention should be paid to the distinction between the quality of arguments regarding the type of actors (70).

Conclusions

As the framing of public health issues in media potentially influences public opinion and policy adoption and implementation, we aimed to get more insight into the actors’ viewpoints and arguments in Dutch newspapers regarding food policies. This study found that arguments tended to concentrate on roles of responsibility whereby opponents tended to reject government interference in general rather than of food specific policies. Insights from this study may serve as a basis for further and deepening research into why certain arguments are used and what their effect is on collective attitudes and policy action.

Availability of data and materials

The datasets generated and/or analyzed during the current study are available through Supplementary Materials.

Abbreviations

- NCDs:

-

Non-communicable diseases

- SSB:

-

Sugar-sweetened beverages

- SRQR:

-

Standards for Reporting Qualitative Research

References

Noncommunicable diseases: World Health Organization; 2022. Available from: https://www.who.int/news-room/fact-sheets/detail/noncommunicable-diseases.

GBD 2019 Risk Factors Collaborators. Global burden of 87 risk factors in 204 countries and territories, 1990–2019: a systematic analysis for the Global Burden of Disease Study 2019. Lancet. 2020 Oct 17;396(10258):1223–1249. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0140-6736(20)30752-2. PMID: 33069327; PMCID: PMC7566194.

Hyseni L, Atkinson M, Bromley H, Orton L, Lloyd-Williams F, McGill R, et al. The effects of policy actions to improve population dietary patterns and prevent diet-related non-communicable diseases: scoping review. Eur J Clin Nutr. 2017;71(6):694–711.

Gortmaker SL, Swinburn BA, Levy D, Carter R, Mabry PL, Finegood DT, et al. Changing the future of obesity: science, policy, and action. Lancet. 2011;378(9793):838–47.

Swinburn BA, Sacks G, Hall KD, McPherson K, Finegood DT, Moodie ML, et al. The global obesity pandemic: shaped by global drivers and local environments. Lancet. 2011;378(9793):804–14.

Sinclair B, Sing F. Building momentum: lessons on implementing a robust sugar sweetened beverage tax. World Cancer Research Fund International; 2018. Available at www.wcrf.org/buildingmomentum.

Teng AM, Jones AC, Mizdrak A, Signal L, Genc M, Wilson N. Impact of sugar-sweetened beverage taxes on purchases and dietary intake: Systematic review and meta-analysis. Obes Rev. 2019;20(9):1187–204.

Secretary-General United Nations. Prevention and control of non-communicable diseases : report of the Secretary-General. 2011. https://www.un.org/en/ga/ncdmeeting2011/documents.shtml.

Using price policies to promote healthier diets. World Health Organization; 2015. https://iris.who.int/bitstream/handle/10665/156403/9789289050821-eng.pdf.

Task Force on Fiscal Policy for Health . Health Taxes to Save Lives: Employing Effective Excise Taxes on Tobacco, Alcohol, and Sugary Beverages. Chairs: Michael R. Bloomberg and Lawrence H. Summers. New York: Bloomberg Philanthropies; 2019. Available at: https://www.bloomberg.org/program/public-health/task-force-fiscal-policy-health/.

Tackling NCDs - Best Buys. Geneva: World Health Organization; 2017. https://iris.who.int/bitstream/handle/10665/259232/WHO-NMH-NVI-17.9-eng.pdf.

Protecting children from the harmful impact of food marketing: policy brief. World Health Organization; 2022.

Popkin BM, Ng SW. Sugar-sweetened beverage taxes: lessons to date and the future of taxation. PLoS Med. 2021;18(1):e1003412.

Pineda E, Poelman MP, Aaspõllu A, Bica M, Bouzas C, Carrano E, et al. Policy implementation and priorities to create healthy food environments using the Healthy Food Environment Policy Index (Food-EPI): A pooled level analysis across eleven European countries. Lancet Reg Health Eur. 2022;23:100522.

Djojosoeparto SK, Kamphuis CBM, Vandevijvere S, Poelman MP. How can National Government Policies Improve Food Environments in the Netherlands? Int J Public Health. 2022;67:1604115.

National Prevention Agreement’s ambitions for smoking may be feasible, more measures necessary to reduce overweight and alcohol use | RIVM. (2018). Available from: https://www.rivm.nl/en/news/national-prevention-agreements-ambitions-for-smoking-may-be-feasible-more-measures-necessary.

Lelieveldt H. Food industry influence in collaborative governance: the case of the Dutch Prevention Agreement on Overweight. Food Policy. 2023;114:102380. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.foodpol.2022.102380.

van de Goor I, Hämäläinen RM, Syed A, Juel Lau C, Sandu P, Spitters H, et al. Determinants of evidence use in public health policy making: Results from a study across six EU countries. Health Policy. 2017;121(3):273–81.

Cullerton K, Donnet T, Lee A, Gallegos D. Playing the policy game: a review of the barriers to and enablers of nutrition policy change. Public Health Nutr. 2016;19(14):2643–53.

Becker W, Helsing E. Food and health data: their use in nutrition policy-making. Copenhagen: World Health Organization. Regional Office for Europe; 1991.

Clarke B, Swinburn B, Sacks G. The application of theories of the policy process to obesity prevention: a systematic review and meta-synthesis. BMC Public Health. 2016;16(1):1084.

Campos PA, Reich MR. Political Analysis for Health Policy Implementation. Health Syst Reform. 2019;5(3):224–35.

Mayes R, Armistead B. Chronic disease, prevention policy, and the future of public health and primary care. Med Health Care Philos. 2012;16(4):691–7.

Baumgartner FR, Green-Pedersen C, Jones BD. Comparative studies of policy agendas. J Eur Public Policy. 2006;13(7):959–74. https://doi.org/10.1080/13501760600923805.

True JL, Jones BD, Baumgartner FR. Punctuated-equilibrium theory: explaining stability and change in public policymaking. In: Sabatier P, editor. Theories of the Policy Process. Second ed. https://www.un.org/en/ga/ncdmeeting2011/documents.shtml.

Burstein P. The impact of public opinion on public policy: a review and an agenda. Polit Res Q. 2003;56(1):29–40.

Soroka SN, Wlezien C. Degrees of democracy: Politics, public opinion, and policy: Cambridge University Press; 2010. Available at www.wcrf.org/buildingmomentum.

Baker P, Gill T, Friel S, Carey G, Kay A. Generating political priority for regulatory interventions targeting obesity prevention: an Australian case study. Soc Sci Med. 2017;177:141–9.

Rock MJ, McIntyre L, Persaud SA, Thomas KL. A media advocacy intervention linking health disparities and food insecurity. Health Educ Res. 2011;26(6):948–60.

Bou-Karroum L, El-Jardali F, Hemadi N, Faraj Y, Ojha U, Shahrour M, et al. Using media to impact health policy-making: an integrative systematic review. Implement Sci. 2017;12(1):52.

Entman RM. Framing: Toward Clarification of a Fractured Paradigm. J Commun. 2006;43(4):51–8.

McCombs ME, Shaw DL. The agenda-setting function of mass media. Public Opin Q. 1972;36(2):176–92.

Vliegenthart R, Walgrave S, Baumgartner FR, Bevan S, Breunig C, Brouard S, et al. Do the media set the parliamentary agenda? A comparative study in seven countries. Eur J Polit Res. 2016;55:283–301.

Mutz DC, Soss J. Reading Public Opinion: The Influence of News Coverage on Perceptions of Public Sentiment. Public Opin Q. 1997;61(3):431–51.

Soroka S, Maioni A, Martin P. What Moves Public Opinion on Health Care? Individual Experiences, System Performance, and Media Framing. J Health Polit Policy Law. 2013;38(5):893–920.

McCombs M. Setting the agenda: the mass media and public opinion. 2008. https://www.un.org/en/ga/ncdmeeting2011/documents.shtml.

Tewksbury D, Scheufele D. News Framing Theory and Research. 4th ed. 2009. p. 17–33. https://www.un.org/en/ga/ncdmeeting2011/documents.shtml.

Shehata A, Andersson D, Glogger I, Hopmann DN, Andersen K, Kruikemeier S, et al. Conceptualizing long-term media effects on societal beliefs. Ann Int Commun Assoc. 2021;45(1):75–93. https://doi.org/10.1080/23808985.2021.1921610.

Jann W, Wegrich K. Theories of the Policy Cycle. In: Fischer F, Müller GJ, Sidney MS, editors. Handbook of Public Policy Analysis. 1st ed. Routledge; 2007. p. 20. Available at www.wcrf.org/buildingmomentum.

Hilton S, Buckton CH, Patterson C, Katikireddi SV, Lloyd-Williams F, Hyseni L, et al. Following in the footsteps of tobacco and alcohol? Actor discourse in UK newspaper coverage of the Soft Drinks Industry Levy. Public Health Nutr. 2019;22(12):2317–28.

Cicchini S, Russell C, Cullerton K. The relationship between volume of newspaper coverage and policy action for nutrition issues in Australia: a content analysis. Public Health. 2022;210:8–15.

Beauchamp DE. Public Health as Social Justice. Inquiry. 1976;13(1):3–14. Available from: http://www.jstor.org/stable/29770972.

Moerschel KS, von Philipsborn P, Hawkins B, McGill E. Concepts of responsibility in public health policy: a systematic scoping review. Health Policy. 2022;126(6):479-89.44.

Rowbotham S, McKinnon M, Marks L. Hawe P. A narrative synthesis. Soc Sci Med: Research on media framing of public policies to prevent chronic disease; 2019. p. 237.

O’Brien BC, Harris IB, Beckman TJ, Reed DA, Cook DA. Standards for reporting qualitative research: a synthesis of recommendations. Acad Med. 2014;89(9):1245–51. https://doi.org/10.1097/ACM.0000000000000388.

Nationaal Onderzoek Multimedia 2023. Available from: https://www.nommedia.nl/.

Swinburn B, Sacks G, Vandevijvere S, Kumanyika S, Lobstein T, Neal B, et al. INFORMAS (International Network for Food and Obesity/non-communicable diseases Research, Monitoring and Action Support): overview and key principles. Obes Rev. 2013;14(Suppl 1):1–12.

Kelishadi R, Farajian S. The protective effects of breastfeeding on chronic non-communicable diseases in adulthood: A review of evidence. Adv Biomed Res. 2014;3:3.

Hawkins B, Holden C. Framing the alcohol policy debate: industry actors and the regulation of the UK beverage alcohol market. Crit Policy Stud. 2013;7(1):53–71.

Fogarty AS, Chapman S. Advocates, interest groups and Australian news coverage of alcohol advertising restrictions: content and framing analysis. BMC Public Health. 2012;12:727.

Warenwetbesluit Meel en brood. 2020. Wetten.Overheid.Nl. https://wetten.overheid.nl/BWBR0009669/2020-07-01

Warenwetbesluit Vlees, gehakt en vleesproducten. 2019. Wetten.Overheid.Nl. https://wetten.overheid.nl/BWBR0009675/2019-12-14

Wet op de verbruiksbelasting van alcoholvrije dranken. 2023. Wetten.Overheid.Nl. https://wetten.overheid.nl/BWBR0005802/2024-01-01

Verduurzaamde vruchtenproducten 2002. 2017. Wetten.Overheid.Nl. https://wetten.overheid.nl/BWBR0013972/2017-07-01/

The National Prevention Agreement. Ministry of Health, Welfare and Sport; 2018. https://www.government.nl/documents/reports/2019/06/30/the-national-prevention-agreement.

Harrison S. Shouts and whispers: The lobbying campaigns for and against resale price maintenance. Eur J Mark. 2000;34(1/2):207–22.

Friedman LC, Cheyne A, Givelber D, Gottlieb MA, Daynard RA. Tobacco Industry Use of Personal Responsibility Rhetoric in Public Relations and Litigation: Disguising Freedom to Blame as Freedom of Choice. Am J Public Health. 2015;105(2):250–60. https://doi.org/10.2105/AJPH.2014.302226.

Michielsen Y. Tablesdebates. 2022. Available from: https://www.tabledebates.org/blog/government-stay-away-our-meatball-how-populism-stops-us-eating-less-meat.

Ulucanlar S, Lauber K, Fabbri A, Hawkins B, Mialon M, Hancock L, et al. Corporate Political Activity: Taxonomies and Model of Corporate Influence on Public Policy. Int J Health Policy Manag. 2023;12(1):1–22. https://doi.org/10.34172/ijhpm.2023.7292.

Petticrew M, Katikireddi SV, Knai C, Cassidy R, Maani Hessari N, Thomas J, et al. “Nothing can be done until everything is done”: the use of complexity arguments by food, beverage, alcohol and gambling industries. J Epidemiol Community Health. 2017;71(11):1078–83. https://doi.org/10.1136/jech-2017-209710.

Paraje G, Colchero A, Wlasiuk JM, Sota AM, Popkin BM. The effects of the Chilean food policy package on aggregate employment and real wages. Food Policy. 2021;100: 102016. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.foodpol.2020.102016.

Paraje G, Montes de Oca D, Wlasiuk JM, Canales M, Popkin BM. Front-of-Pack Labeling in Chile: Effects on Employment, Real Wages, and Firms' Profits after Three Years of Its Implementation. Nutrients. 2022;14(2):295. https://doi.org/10.3390/nu14020295.

Law C, Cornelsen L, Adams J, Penney TL, Rutter H, White M, et al. An analysis of the stock market reaction to the announcements of the UK Soft Drinks Industry Levy. Econ Hum Biol. 2020;38: 100834. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ehb.2019.100834.

Hesselman M, Toebes B. The Human Right to Health and Climate Change: A Legal perspective. Soc Sci Res Netw. 2015. https://doi.org/10.2139/ssrn.2688544.

Garde A, Byrne S, Gokani N, Murphy B. For a Children’s Rights Approach to Obesity Prevention: The Key Role of an Effective Implementation of the WHO Recommendations. Eur J Risk Regul. 2017;8(2):327–41. https://doi.org/10.1017/err.2017.26.

United Nations Children’s Fund and United Nations Special Rapporteur on the Right to Food. Protecting Children’s Right to a Healthy Food Environment. Geneva: UNICEF and United Nations Human Rights Council; 2019.

White LE. Understanding the policy and public debate surrounding the regulation of online advertising of high in fat, sugar and salt food and beverages to children [dissertation]. Glasgow: University of Glasgow; 2020.

Shojaie A, Fox EB. Granger Causality: a review and recent advances. Annu Rev Stat Its Appl. 2022;9(1):289–319. https://doi.org/10.1146/annurev-statistics-040120-010930.

McKee M, van Schalkwyk MC, Stuckler D. The second information revolution: digitalization brings opportunities and concerns for public health. Eur J Public Health. 2019;29(Suppl 3):3–6. https://doi.org/10.1093/eurpub/ckz160.

Acknowledgements

Not applicable.

Funding

JDM was funded through an ZonMw Vidi project ‘Profits or public health?’ (grant no. 09150172210046). The funder had no role in study design, data collection and analysis, decision to publish, or preparation of the manuscript.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

NMSD conducted the formal analysis and wrote a first draft of the manuscript. NS, MPP, SCD and JDM critically revised the manuscript. SCD and JDM supervised the project. JDM conceived of the study idea. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate

Not applicable. Since the analysis concerned newspaper articles and not humans, no ethics approval was required.

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Competing interests

Author JDM is a member of the Editorial Board of International Journal of Behavioral Nutrition and Physical Activity. JDM was not involved in the journal’s peer review process of, or decisions related to, this manuscript. The authors declare that they have no other competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary Information

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/. The Creative Commons Public Domain Dedication waiver (http://creativecommons.org/publicdomain/zero/1.0/) applies to the data made available in this article, unless otherwise stated in a credit line to the data.

About this article

Cite this article

Droog, N.M.S., Dijkstra, C.S., van Selm, N. et al. Unveiling viewpoints on national food environment policies in the Dutch newspaper discourse: an interpretative media content analysis. Int J Behav Nutr Phys Act 21, 80 (2024). https://doi.org/10.1186/s12966-024-01625-3

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/s12966-024-01625-3