Abstract

Background

Pictorial health warnings on sugar-sweetened beverages (SSBs) are a promising policy for preventing diet-related disease in children. A recent study found that pictorial warnings reduced parents’ purchases of SSBs for their children by 17%. However, the psychological mechanisms through which warnings affect parental behavior remain unknown. We aimed to identify the mechanisms that explain how pictorial warnings affect parents’ SSB purchasing behavior for their children using secondary data from a randomized trial.

Methods

In 2020–2021, parents of children ages 2 to 12 years (n = 325) completed a shopping task in a convenience store laboratory in North Carolina, USA. Participants were randomly assigned to a pictorial warnings arm (SSBs displayed pictorial health warnings about type 2 diabetes and heart damage) or a control arm (SSBs displayed a barcode label). Parents then bought a beverage for their child and took a survey measuring 11 potential psychological mediators, selected based on health behavior theories and a model explaining the impact of tobacco warnings. We conducted simple mediation analyses to identify which of the 11 mechanisms mediated the impact of exposure to pictorial warnings on purchasing any SSBs for their children.

Results

Two of the 11 constructs were statistically significant mediators. First, the impact of pictorial warnings on the likelihood of purchasing any SSB was mediated by parents’ perceptions that SSBs were healthier for their child (mediated effect= −0.17; 95% CI = − 0.33, − 0.05). Second, parents’ intentions to serve SSBs to their children also mediated the effect of warnings on likelihood of purchasing any SSB (mediated effect= −0.07, 95% CI=-0.21, − 0.003).

Conclusions

Pictorial warnings reduced parents’ purchases of SSBs for their children by making parents think SSBs are less healthful for their children and reducing their intentions to serve SSBs to their children. Communication approaches that target healthfulness perceptions and intentions to serve SSBs may motivate parents to buy fewer SSBs for their children.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Consumption of sugar-sweetened beverages (SSBs) is associated with numerous health problems in children, including obesity and dental caries [1, 2]. Parents have a large influence on the types of foods and drinks that children consume [3, 4]. Informing parents about the health harms associated with SSBs is therefore a promising strategy for reducing children’s SSB consumption. One policy that could help inform parents and reduce SSB purchases is requiring SSB containers to display warning labels [5, 6]. Since 2011, nine US jurisdictions have proposed legislation requiring that warnings stating the health consequences of SSBs be displayed on SSB containers, advertisements, or at the point of sale [7]. Globally, 10 countries have passed laws to require nutrient warnings on foods and beverages that exceed thresholds for nutrients of concern, including warnings about high sugar content in SSBs [8].

Mounting research indicates that SSB warnings are a promising tool for reducing parents’ selection of SSBs for their children. Three experiments have found that warnings on SSBs reduced parents’ hypothetical selection [9, 10] and purchasing of SSBs [11] for their children. However, the mechanisms explaining the impact of SSB warnings on parents’ behavior remain unclear. Understanding these mechanisms could suggest actionable strategies for designing SSB warnings that can more effectively reduce parents’ purchases of SSBs for their children. For example, if SSB warnings reduce parents’ purchases by heightening attention to the warnings, policymakers should design warnings with the goal of attracting as much attention as possible. Identifying the mechanisms of impact among parents can also inform the design of other communication approaches to reduce children’s SSB consumption, such as mass media campaigns.

Health behavior theories and research suggest several potential mechanisms of SSB warnings’ impact. First, warnings could change behavior by eliciting message reactions – that is, parents’ immediate processing of the message in their head or body. For example, warnings could change behavior by grabbing parents’ attention, causing them to feel negative emotions such as fear, or by prompting them to think about the harms of using a product. Multiple theories provide support for these reactions being mechanisms of behavior change, including the Elaboration Likelihood Model [12] and the Extended Parallel Process Model [13]. Other potential mediators of SSB warnings’ impacts include attitudes and beliefs about SSBs. Theories such as the Health Belief Model [14, 15] and Theory of Planned Behavior [16] posit that attitudes and beliefs could be powerful mechanisms of behavior change. For example, SSB warnings could change parents’ purchase behaviors by changing their perceptions of healthfulness of SSBs for their children and perceived likelihood of SSBs causing health problems in children. Finally, the Theory of Planned Behavior [16] and Theory of Reasoned Action [17] posit that behavioral intentions are mediators of behavior change [16], a finding that has been supported by prior mediation studies of warnings [18, 19].

Two studies have examined how warnings change behavior among adults shopping for themselves, finding that SSB warnings reduced SSB purchasing or selection primarily by heightening message reactions [19, 20]. Similar to the studies with adults making decisions for themselves, one study of parents found that negative emotional reactions mediated the impact of warnings on parents’ hypothetical selection of SSBs for their children [10]. However, a second study of parents’ hypothetical beverage purchases for their children found that warnings worked by making parents think SSBs were less healthy [21], a construct that typically does not play a role in how warnings affect general adult populations. It is possible that healthfulness perceptions are more important for parents acting on behalf of their children than for adults shopping for themselves because parents rate nutritional quality as the most important factor they consider when selecting foods for their children [22]. Although initial studies of mediators with parents are suggestive, these studies did not assess parents’ actual purchase behaviors. Studies with objective purchasing outcomes are necessary to provide a more externally valid evaluation of mediators of SSB warnings’ effects among parents. To fill this gap, this study aimed to examine mediators of the impact of pictorial SSB health warnings on parents’ purchases of SSBs for their children.

Methods

Participants

The current study used secondary data from a randomized trial with 326 parents of children ages 2–12 years old [11]. From January to March 2020, we recruited trial participants from Central North Carolina through in-person recruitment, flyers, email listservs, Craigslist ads, Facebook ads, and word of mouth. To mask the purpose of the trial, all study materials stated that the study sought to understand the factors that affect consumers’ purchasing decisions in a convenience store environment. Due to COVID-19, we paused recruitment and enrollment beginning in March 2020, and resumed recruitment in October 2020 after implementing a COVID-19 safety protocol. Study enrollment was completed in March 2021.

To be eligible, participants had to be at least 18 years of age and the parent or guardian (hereafter “parent”) of at least one child ages 2–12 years old who consumed at least one SSB in the past week. Additionally, participants had to be able to read and speak English or Spanish, use a tablet or computer to take a survey, and attend one in-person study visit. The University of North Carolina Institutional Review Board approved the study (IRB #19–0277) and participants provided written informed consent. All study materials were available in English and Spanish.

Setting

The study took place at the UNC Mini Mart, a 245-square-foot convenience store designed for research purposes, in Chapel Hill, NC [23]. The Mini Mart contains a commercial refrigerator, gondola shelving units, and a check-out stand with a point-of-sale system. We stocked the Mini Mart with 33 types of single-serving beverages, more than 130 types of food items, and 31 household good items. To determine which beverages to stock, we used 2014 Nielsen Homescan Data to examine top selling beverages at convenience stores in the US among households with children in each of 6 beverage categories: fruit-flavored drinks, sodas, flavored milks, sports and energy drinks, flavored waters, and sweet teas. For every SSB sold, there was a comparable non-sugary option displayed next to the SSB in the refrigerator. All SSBs and their non-sugary equivalents were sold for the same price. A validation study with parents found that nearly all participants reported that their Mini Mart purchases were similar to their typical purchases (96%), the Mini Mart felt like a real store (94%), and they could imagine doing their shopping in the Mini Mart (92%) [23]. Rates of SSB purchasing were similar in the store as compared to real-world purchases measured via receipts [23].

Procedures

The trial used a parallel arm study design, with staff randomly assigning participants to one of the two trial arms: pictorial warnings or control labels. Staff prepared the Mini Mart before a participant’s arrival based on the assigned trial arm. In the pictorial warnings arm, staff applied one of two warning labels (Fig. 1) to the front of all SSBs in the Mini Mart. The two pictorial warnings read “WARNING: Excess consumption of drinks with added sugar contributes to type 2 diabetes” and “WARNING: Excess consumption of drinks with added sugar contributes to heart damage” and were accompanied by photographs representing each of the topics. As reported previously [24], we developed the warnings through a multiphase process with a professional designer, a stakeholder advisory board, and two rounds of quantitative pre-testing. About half of the SSBs in the Mini Mart displayed the heart damage warning label, and the other half displayed the type 2 diabetes label. In the control arm, staff applied a neutral barcode label to all SSBs to control for the presence of a study label and for the amount of branding obscured by the label.

Before participants entered the store, staff instructed them to select one snack and one beverage for their child, as well as one household item. This shopping task was designed to mask the purpose of the study. Research staff informed the participants that one of the items would be randomly selected at the checkout counter for the participant to take home. After the shopping task, participants completed a survey programmed in Qualtrics on a computer or tablet in a separate room. Participants received the beverage and cash for a total value of $40 for their participation in the study.

Measures

In the current study, we examined mediators of the impact of the pictorial warnings on purchasing any SSBs in the Mini Mart (yes/no), which was the primary outcome for both this study and the main trial [11]. We also examined mediation of the impact of pictorial warnings on SSB calories purchased in the Mini Mart as a secondary outcome, for comparability with a similar mediation study with text-only warnings on SSBs [19].

The survey assessed a range of potential psychological mediators using measures adapted or used verbatim from previous studies (Supplementary Table 1). We examined three categories of potential mediators: message reactions, attitudes and beliefs, and intentions, drawing on research from prior SSB warning studies [5, 6, 25, 26], as well as health communication and behavior theories [12, 13, 27, 28].

First, the survey assessed three different message reactions: attention to the labels, negative emotional reactions, and thinking about the harms of SSBs. Second, the survey assessed six types of attitudes and beliefs, including perceived amount of added sugar in SSBs, perceived healthfulness of SSBs for their child, appeal of SSBs for their child, perceived tastiness of SSBs for their child, perceived likelihood of child experiencing health problems due to SSBs, and injunctive norms to limit SSBs for their child (i.e., the perception that other people want them to limit SSBs for their child). Finally, the survey assessed two types of intentions: anticipated social interactions (i.e., intentions to talk to others about the study labels) and intentions to serve SSBs to their child in the next week. All of the mediators used response scales ranging from low values coded as 1 to high values coded as 5, except for intentions to serve SSBs to their child, which ranged from 0 times to 21 times per week.

Analysis

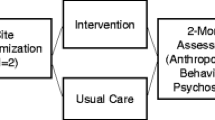

The analytic sample included 325 participants with complete data on the primary outcome in the main trial, excluding one person with missing data on the primary outcome of purchasing any SSB. Mediation analyses used the MacKinnon approach [29], assessing the impact of trial arm on the mediator (a pathway), the association of the mediator with the outcome while controlling for trial arm (b pathway), and the product of the a-pathway and the b-pathway (i.e., the indirect or mediated effect, a*b; Fig. 2). We opted to test single mediator models as a first step in understanding the independent effects of each potential mechanism and to avoid potential collinearity among a large number of mediators with some conceptual overlap.

Analyses used the PROCESS macro for SPSS (version 4.1) [30] using bootstrapped 95% confidence intervals with 10,000 repetitions; this approach does not assume that indirect effects are normally distributed [31]. We repeated these models for each of the two outcomes (purchase of any SSB and calories purchased from SSBs). All mediators were treated as linear variables in modeling since they were all measured continuously. We determined that mediation had occurred if the 95% confidence interval around the indirect effect did not cross zero. Models of purchasing any SSB were estimated using logistic regression; models of calories purchased from SSBs were estimated using OLS regression. As there were limited missing data on the mediators (0–17 observations depending on variable; no more than 5% participants had missing data on any of the mediators), we used complete case analyses for each model. We calculated the proportion of the total effect mediated for each significant mediator for the models with calories purchased from SSBs as the outcome (indirect effect/total effect). We did not calculate the proportion of the total effect mediated for the effect of warnings on parents’ likelihood of purchasing any SSBs because the PROCESS macro does not estimate the total effect for dichotomous outcomes.

We planned not to adjust for covariates in based on CONSORT 2010 guidance for RCTs recommending that adjustment is only needed for variables with strong prognostic strength (e.g., stratification variables) [32]. However, we performed sensitivity analyses to explore whether adjustment might be warranted for the mediation analyses. We first examined the correlation between key demographics (i.e., age, ethnicity, educational attainment, and annual household income) and the primary outcome of purchasing any SSBs. We planned to re-run the mediation analyses controlling for any characteristics that were significantly correlated with the primary outcome; however, there were no significant correlations, so the mediation models did not include any covariates.

Results

Parents’ mean age was 38 years, and most (77%) were women (Table 1). Slightly fewer than half (45%) were non-Hispanic white, 25% were non-Hispanic Black, and 20% were Latino/a. About half (55%) of participants had an annual household income under $50,000, and 42% had a high school diploma or less education. About a third (38%) of participants shopped for a child ages 2–5 years, and 62% shopped for a child ages 6–12 years.

Impact of pictorial warnings on mediators

Pictorial warnings influenced 8 of the 11 hypothesized mediators (a pathway), as reported previously [11] (Table 2). Pictorial warnings changed all three message reactions, leading to greater attention, negative emotional reactions, and thinking about the harms of drinking SSBs (all p < .001). Pictorial warnings changed two of six attitudes and beliefs: warnings led to lower perceptions that SSBs are healthy for their child (p < .01) as well as stronger injunctive norms to limit serving SSBs to their child (p = .01). Pictorial warnings did not elicit changes in perceived amount of added sugar in SSBs, appeal of SSBs for child, perceived tastiness of SSBs for child, or perceived likelihood of child having health problems due to SSBs (all p > .05). Finally, pictorial warnings led to greater anticipated social interactions and lower intentions to serve SSBs to their child (both p < .05).

Association of mediators on purchasing SSBs

When examining the associations between mediators and purchasing any SSBs, controlling for trial arm (b pathway), parents’ perceptions that SSBs were healthier for their children were associated with higher likelihood of purchasing SSBs (p < .001). Higher perceived likelihood of child having health problems due to SSBs was associated with a lower likelihood of purchasing SSBs (p < .05). Finally, higher intentions to serve SSBs to one’s child was associated with a greater likelihood of purchasing (p < .05).

Mediation

Two of the 11 potential mechanisms were significant mediators of the impact of SSB warnings on parents’ likelihood of buying any SSB for their child (Table 2). Perceived healthfulness of SSBs mediated the effect: pictorial warnings led to lower perceptions that SSBs are healthy for their child (a pathway=-0.26), which in turn was associated with a lower likelihood of purchasing of SSBs (b pathway = 0.64), resulting in a mediated effect of − 0.17 (95% CI = − 0.33, − 0.05). Intentions to serve SSBs also mediated the effect, such that pictorial warnings led to lower intentions to serve SSBs to their child (a pathway=−0.35), which in turn was associated with a lower likelihood of purchasing SSBs (b pathway = 0.20), resulting in a mediated effect of − 0.07 (95% CI= −0.21, − 0.003). When examining mediators of the impact of SSB warnings on calories purchased from SSBs (our secondary outcome), perceived healthfulness and intentions to serve SSBs were the only two statistically significant mediators, following the same pattern as for purchasing any SSBs (Table 3). Perceived healthfulness mediated 22% of the total effect of warnings on calories purchased, whereas intentions to serve SSBs mediated 9% of the total effect.

Discussion

In this study, we found that pictorial health warnings reduced parents’ purchases of SSBs for their children by reducing the perceived healthfulness of SSBs. Additionally, pictorial warnings changed parents’ purchase behavior by lowering their intentions to serve SSBs to their children, in line with health behavior theories (e.g., the Theory of Planned Behavior) that posit that behavioral intentions predict behavior change [16, 17].

We found that perceived healthfulness of SSBs partially explained how SSB warnings reduced parents’ likelihood of purchasing an SSB for their child. SSB warnings led to lower perceptions that SSBs are healthy for their child, which in turn was associated with a lower likelihood of purchasing of SSBs. Additionally, higher perceived likelihood that SSBs could lead to health problems for their child was associated with a lower likelihood of parents purchasing SSBs (though perceived disease likelihood was not a significant mediator). These findings are in line with a prior study that found that parents’ healthfulness and risk perceptions mediated the impact of health warnings on hypothetical selection of SSBs for their children [21]. Together, these findings suggest that communications approaches about SSBs directed toward parents (including warnings) may be more effective if they focus on SSBs’ poor nutritional quality and the health harms associated with overconsuming these products. Warnings may be especially effective for changing beliefs about some SSB types, such as fruit drinks, that are frequently marketed to appear healthful [33,34,35,36] and that bear marketing claims known to cause parents to hold incorrect beliefs about the products’ nutritional quality [37].

In our study, message reactions did not mediate the impact of SSB warnings on parents’ purchases of SSBs. These results stand in contrast to two prior studies with adults, finding that message reactions including emotions and thinking about harms, explained how SSB warnings affected adults’ purchase behaviors and intentions [19, 20]. The findings also stand in contrast with one study among parents finding that negative emotional reactions mediated the impact of SSB warnings on selection of SSBs for their child [10]. The results in the present study also contrast with studies finding that message reactions are key mediators of the impact of tobacco warnings on adults’ tobacco-related intentions and behavior [18, 38,39,40,41,42]. In the current study, SSB warnings affected all three message reactions including attention, negative emotions, and thinking about the risks of SSBs, but these changes did not influence parents’ selection of SSBs. Our finding that healthfulness perceptions explained how warnings affected parents also differs from prior studies of mediators underlying both SSB and cigarette warnings’ impacts in general adult populations [18, 19].

The differences in mediators between prior studies of adults and the present study of parents suggest that that the process of reacting to health messages might function differently when making purchasing decisions for oneself, compared to when making decisions about another person (perhaps especially when that person is one’s child). One possible explanation for these differences is that message reactions are processes that reflect an individual’s thoughts and feelings, but do not involve considerations for others. Another possibility is that parents are less informed about what beverages are healthy for their children than for themselves, giving warnings more room to changing healthfulness perceptions. Consistent with this hypothesis, prior research shows that parents tend to believe certain types of SSBs including fruit drinks and sports drinks are healthy options for their children [21, 35, 43] and that warnings can help correct misperceptions about these beverages [21]. Whatever the explanation, the differences in mediation patterns among adults buying products for themselves [19, 20] and parents buying for their children in the current study indicates that future studies should examine mediation patterns separately for these two populations.

Overall, we found many small effects in our models, which mirrors prior research that health communication interventions often lead to a small (~ 5%) change in a desired outcomes [44]. In terms of the mediated effects, we found that perceived healthfulness mediated 22% of the total effect of warnings on calories purchased, whereas intentions to serve SSBs mediated 9% of the total effect. These findings suggest that other unmeasured mechanisms of influence could be acting as important mediators; future studies should examine a broader range of mediators.

Strengths of this study include the randomized controlled design. We also assessed an objective purchasing outcome in the context of naturalistic experimental store setting with a wide variety of real products. Limitations include that participants had only one exposure to the warning labels and mediators and outcomes were measured at only one timepoint. Additional studies should establish patterns of mediation over a longer time period and explore serial mediation using longitudinal data. Finally, it is possible that our surveys did not measure all possible mediators of warning labels; future studies including qualitative research could shed light on potential psychological mediators not assessed in this study.

Conclusions

This randomized trial found that pictorial SSB warnings reduced parents’ purchases of SSBs for their children by making parents think SSBs are less healthful for their children and changing parents’ intentions about serving SSBs. These results stand in contrast to prior studies showing that message reactions explain the impact of warnings on adults’ SSB purchases for themselves, and suggest that different mechanisms may underly warning effects for parents purchasing for their children compared to adults purchasing drinks for themselves. Warnings and other communications approaches targeting healthfulness perceptions and intentions may be particularly effective for reducing parents’ purchases of SSBs for their children.

Data Availability

The dataset and syntax used in the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

Abbreviations

- SSB:

-

Sugar-sweetened beverage

References

Malik VS, Pan A, Willett WC, Hu FB. Sugar-sweetened beverages and weight gain in children and adults: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Am J Clin Nutr. 2013;98(4):1084–102.

Bleich SN, Vercammen KA. The negative impact of sugar-sweetened beverages on children’s health: an update of the literature. BMC Obes. 2018;5:6.

Poti JM, Popkin BM. Trends in energy intake among US children by eating location and food source, 1977–2006. J Am Diet Assoc. 2011;111(8):1156–64.

Grimm GC, Harnack L, Story M. Factors associated with soft drink consumption in school-aged children. J Am Diet Assoc. 2004;104(8):1244–9.

Grummon AH, Hall MG. Sugary drink warnings: a meta-analysis of experimental studies. PLoS Med. 2020;17(5):e1003120.

An R, Liu J, Liu R, Barker AR, Figueroa RB, McBride TD. Impact of Sugar-Sweetened Beverage warning labels on consumer behaviors: a systematic review and Meta-analysis. Am J Prev Med. 2021;60(1):115–26.

Pomeranz JL, Mozaffarian D, Micha R. Sugar-Sweetened Beverage warning policies in the broader legal context: health and safety warning laws and the First Amendment. Am J Prev Med. 2020.

UNC Global Food Research Program. Countries with mandatory warning labels on packaged foods and drinks 2022 [Available from: https://www.globalfoodresearchprogram.org/wp-content/uploads/2022/08/FOP_Regs_maps_2022_08.pdf.

Roberto CA, Wong D, Musicus A, Hammond D. The influence of sugar-sweetened beverage health warning labels on parents’ choices. Pediatrics. 2016;137(2):e20153185.

Mantzari E, Vasiljevic M, Turney I, Pilling M, Marteau T. Impact of warning labels on sugar-sweetened beverages on parental selection: an online experimental study. Prev Med Rep. 2018;12:259–67.

Hall MG, Grummon AH, Higgins ICA, Lazard AJ, Prestemon CE, Avendaño-Galdamez MI et al. The impact of pictorial health warnings on purchases of sugary drinks for children: a randomized controlled trial. PLoS Med. 2022.

Petty RE, Cacioppo JT. The elaboration likelihood model of persuasion. Adv Exp Soc Psychol. 1986;19:123–205.

Witte K. Putting the fear back into fear appeals: the extended parallel process model. Commun Monogr. 1992;59(4):329–49.

Rosenstock IM. Why people use health services. Milbank Mem Fund Q. 1966:94–127.

Rosenstock IM. Historical origins of the health belief model. Health Educ Behav. 1974;2(4):328–35.

Ajzen I. The theory of planned behavior. Organ Behav Hum Decis Process. 1991;50(2):179–211.

Fishbein M, Ajzen I. Predicting and changing behavior: the reasoned action approach. New York, NY: Psychology Press; 2010.

Brewer NT, Parada H, Hall MG, Boynton MH, Noar SM, Ribisl KM. Understanding why pictorial cigarette pack warnings increase quit attempts. Ann Behav Med. 2019;53(3):232–43.

Grummon AH, Brewer NT. Health Warnings and Beverage Purchase Behavior: mediators of impact. Ann Behav Med. 2020;54(9):691–702.

Donnelly GE, Zatz LY, Svirsky D, John LK. The effect of graphic warnings on sugary-drink purchasing. Psychol Sci. 2018;29(8):1321–33.

Moran AJ, Roberto CA. Health warning labels correct parents’ misperceptions about sugary drink options. Am J Prev Med. 2018;55(2):e19–e27.

Hughner RS, Maher JK. Factors that influence parental food purchases for children: implications for dietary health. J Mark Manage. 2006;22(9–10):929–54.

Hall MG, Higgins ICA, Grummon AH, Lazard AJ, Prestemon CE, Sheldon JM et al. Using a naturalistic store laboratory for clinical trials of point-of-sale nutrition policies and interventions: a feasibility and validation study. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2021;18(16).

Hall MG, Lazard AJ, Grummon AH, Higgins ICA, Bercholz M, Richter APC, et al. Designing warnings for sugary drinks: a randomized experiment with latino parents and non-latino parents. Prev Med. 2021;148:106562.

Taillie LS, Hall MG, Popkin BM, Ng SW, Murukutla N. Experimental studies of front-of-Package nutrient warning labels on Sugar-Sweetened Beverages and Ultra-Processed Foods: a scoping review. Nutrients. 2020;12(2).

Clarke N, Pechey E, Kosīte D, König LM, Mantzari E, Blackwell AKM et al. Impact of health warning labels on selection and consumption of Food and Alcohol Products: systematic review with Meta-analysis. Health Psychol Rev. 2020:1–39.

Rogers RW. A protection motivation theory of fear appeals and attitude change. J Psychol. 1975;91(1):93–114.

Tanner JF Jr, Hunt JB, Eppright DR. The protection motivation model: a normative model of fear appeals. J Mark. 1991:36–45.

MacKinnon DP, Fairchild AJ, Fritz MS. Mediation analysis. Annu Rev Psychol. 2007;58:593–614.

Hayes AF. Introduction to mediation, moderation, and conditional process analysis: a regression-based approach. Guilford publications; 2017.

Hayes AF. Beyond Baron and Kenny: statistical mediation analysis in the new millennium. Commun Monogr. 2009;76(4):408–20.

Moher D, Hopewell S, Schulz KF, Montori V, Gøtzsche PC, Devereaux PJ, et al. CONSORT 2010 explanation and elaboration: updated guidelines for reporting parallel group randomised trials. Int J Surg. 2012;10(1):28–55.

Duffy EW, Hall MG, Carpentier FRD, Musicus AA, Meyer ML, Rimm E, et al. Nutrition claims on fruit drinks are inconsistent indicators of nutritional profile: a content analysis of fruit drinks purchased by households with young children. J Acad Nutr Diet. 2021;121(1):36–46. e4.

Musicus AA, Hua SV, Moran AJ, Duffy EW, Hall MG, Roberto CA et al. Front-of-package claims & imagery on fruit-flavored drinks and exposure by household demographics. Appetite. 2021:105902.

Munsell CR, Harris JL, Sarda V, Schwartz MB. Parents’ beliefs about the healthfulness of sugary drink options: opportunities to address misperceptions. Public Health Nutr. 2016;19(1):46–54.

Pomeranz JL, Harris JL. Children’s Fruit “Juice” Drinks and FDA Regulations: Opportunities to increase transparency and support Public Health. Am J Public Health. 2020:e1–e10.

Hall MG, Lazard AJ, Higgins ICA, Blitstein JL, Duffy EW, Greenthal E, et al. Nutrition-related claims lead parents to choose less healthy drinks for young children: a randomized trial in a virtual convenience store. Am J Clin Nutr. 2022;115(4):1144–54.

Brewer NT, Hall MG, Noar SM, Parada H Jr, Stein-Seroussi A, Bach LE, et al. Effect of pictorial cigarette pack warnings on changes in smoking behavior: a randomized clinical trial. JAMA Intern Med. 2016;176(7):905–12.

Brewer NT, Jeong M, Mendel JR, Hall MG, Zhang D, Parada H Jr, et al. Cigarette pack messages about toxic chemicals: a randomised clinical trial. Tob Control. 2019;28(1):74–80.

Hall MG, Sheeran P, Noar SM, Boynton MH, Ribisl KM, Parada H Jr et al. Negative affect, message reactance and perceived risk: how do pictorial cigarette pack warnings change quit intentions? Tob Control. 2017.

Evans AT, Peters E, Strasser AA, Emery LF, Sheerin KM, Romer D. Graphic warning labels elicit affective and thoughtful responses from smokers: results of a randomized clinical trial. PLoS ONE. 2015;10(12):e0142879.

Peters E, Romer D, Evans A, editors. Reactive and thoughtful processing of graphic warnings: Multiple roles for affect. University of North Carolina, Lineberger Comprehensive Cancer Center, Center for Regulatory Research on Tobacco Communication; 2014; Chapel Hill, NC.

Zytnick D, Park S, Onufrak SJ. Child and caregiver attitudes about Sports Drinks and Weekly Sports drink intake among U.S. Youth. Am J Health Promot. 2016;30(3):e110–9.

Snyder LB. Health communication campaigns and their impact on behavior. J Nutr Educ Behav. 2007;39(2 Suppl):32–40.

Acknowledgements

The authors thank Carmen E. Prestemon and Mirian I. Avendaño-Galdamez for their role in data collection and study coordination. The authors thank the organization El Centro Hispano for their consultation and collaboration on this project.

Funding

Data collection for the randomized trial was supported by grant #76290 from the Robert Wood Johnson Foundation through its Healthy Eating Research program. General support was provided by NIH grant to the Carolina Population Center, grant numbers P2C HD050924 and T32 HD007168. K01HL147713 from the National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute of the NIH supported MGH’s time writing the paper. K01HL158608 from the National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute of the NIH supported AHG’s time writing the paper. F31HD108962 from the National Institute of Child Health and Human Development of the NIH supported APCR’s time writing the paper. We acknowledge recruitment support from the NC Translational and Clinical Sciences (NC TraCS) Institute, which is supported by the National Center for Advancing Translational Sciences (NCATS), National Institutes of Health, through Grant Award Number UL1TR002489. The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the NIH.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

MGH, AHG, AJL, and LST conceptualized the study. MGH, LST, AHG, and AJL acquired funding. ICAH managed the study. TQ analyzed the data. All authors contributed to drafting the manuscript and provided critical feedback on multiple drafts of the paper.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate

The University of North Carolina’s Institutional Review Board approved this study procedures (study # 19–0277).

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Competing interests

None to disclose.

Additional information

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Electronic supplementary material

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/. The Creative Commons Public Domain Dedication waiver (http://creativecommons.org/publicdomain/zero/1.0/) applies to the data made available in this article, unless otherwise stated in a credit line to the data.

About this article

Cite this article

Hall, M.G., Grummon, A.H., Queen, T. et al. How pictorial warnings change parents’ purchases of sugar-sweetened beverage for their children: mechanisms of impact. Int J Behav Nutr Phys Act 20, 76 (2023). https://doi.org/10.1186/s12966-023-01469-3

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/s12966-023-01469-3