Abstract

Background

Physical activity mass media campaigns can deliver physical activity messages to many people, but it remains unclear whether they offer good value for money. We aimed to investigate the cost-effectiveness, cost-utility, and costs of physical activity mass media campaigns.

Methods

A search for economic evaluations (trial- or model-based) and costing studies of physical activity mass media campaigns was performed in six electronic databases (June/2021). The authors reviewed studies independently. A GRADE style rating was used to assess the overall certainty of each modelled economic evaluation. Results were summarised via narrative synthesis.

Results

Twenty-five studies (five model-based economic evaluations and 20 costing studies) were included, and all were conducted in high-income countries except for one costing study that was conducted in a middle-income country. The methods and assumptions used in the model-based analyses were highly heterogeneous and the results varied, ranging from the intervention being more effective and less costly (dominant) in two models to an incremental cost of US$130,740 (2020 base year) per QALY gained. The level of certainty of the models ranged from very low (n = 2) to low (n = 3). Overall, intervention costs were poorly reported.

Conclusions

There are few economic evaluations of physical activity mass media campaigns available. The level of certainty of the models was judged to be very low to low, indicating that we have very little to little confidence that the results are reliable for decision making. Therefore, it remains unclear to what extent physical activity mass media campaigns offer good value for money. Future economic evaluations should consider selecting appropriate and comprehensive measures of campaign effectiveness, clearly report the assumptions of the models and fully explore the impact of assumptions in the results.

Review registration

Similar content being viewed by others

Background

The health and social benefits of physical activity are well established [1]. Physical activity helps with the prevention and management of a range of chronic health conditions, such as coronary heart disease, diabetes and some cancers including bladder, endometrium, esophagus, kidney, lung, and stomach cancers [2]. Physical activity also has a positive impact on mental health, sleep, cognitive health, dementia and falls prevention [3,4,5]. Despite compelling evidence of the benefits of physical activity, high levels of physical inactivity continue to be observed worldwide with 25% of adults and 75% of adolescents globally not meeting the global recommendations for physical activity set by WHO [1, 6, 7]. Population-wide comprehensive strategies are urgently needed to address this issue.

Public education communication campaigns, also known as mass media campaigns, are recognised as one of the components of a comprehensive approach to promoting physical activity. Mass-media campaigns are mentioned in the policy recommendations outlined in the World Health Organization (WHO) Global Action Plan on Physical Activity (GAPPA) 2018-2030 [7]. The recommendation is to implement national and community-level communication campaigns as part of a comprehensive physical activity strategy. Mass media campaigns are also among the “Eight best investments for physical activity” developed by the International Society for Physical Activity and Health (ISPAH) [8].

There are several examples in the literature of mass media campaigns for physical activity promotion, such as the Verb campaign in the USA [9], Push Play campaign in New Zealand [10] and the ParticipACTION campaign in Canada [11]. They employed population-wide strategies, typically using a combination of the mass media communication channels of television, radio and print media [12,13,14]. These campaigns were intended to raise awareness of, improve knowledge about and change attitudes and social norms regarding physical activity, and ultimately influence behaviour change. They are commonly linked to other community-based initiatives, motivational and environmental programs, as well as other strategies to enhance message reach and support behavioural change in order to increase physical activity and examples include the use of pedometers, creation pf physical activity facilities and community-based programs.

Mass media campaigns can deliver specific physical activity messages to a large proportion of the population but do require substantial resources and costs. It is important therefore to establish whether these interventions offer good value for money. Cost-effectiveness analysis is a way to examine the costs and health outcomes of alternative interventions, revealing the trade-offs involved in choosing one intervention over another [15]. Cost-utility analysis is a form of cost-effectiveness analysis in which health effects are measured as multi-dimensional health outcomes that are reduced to a single index, such as quality-adjusted life years (QALYs) or disability adjusted life years (DALYs). The use of a single index provides a common metric that allows broader comparison to be made between treatments for different conditions and populations [16]. To the best of our knowledge there is no systematic review of economic evaluations of physical activity mass media campaigns currently available in the literature.

This review aims to summarise the evidence on economic evaluations and costing studies of physical activity mass media campaigns. It was commissioned by the WHO to inform the development of the WHO ACTIVE toolkits [17] which support countries to implement the policy recommendations outlined in the GAPPA 2018-2030 [7], and the updating of the WHO CHOICE modelling of cost effective interventions for physical activity [7, 18]. The review questions were:

-

1)

What is the cost-effectiveness of physical activity mass media campaigns?

-

2)

What are the costs of developing and implementing physical activity mass media campaigns?

Methods

We followed the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses (PRISMA, Additional file 1: Appendix 1) and guideline recommendations for conducting systematic reviews of economic evaluations for informing evidence-based healthcare decisions [19,20,21,22]. A protocol was prospectively registered and published on the Open Science Framework website (https://bit.ly/3tKSBZ3) [23]. A glossary with definitions of key health economic terms to help understanding of the articles is available in Additional file 1: Appendix 2.

Searches

We searched the following specialised databases and registries from inception to June 2021: Medline (Ovid), Embase (Ovid), the National Institute for Health Research Economic Evaluation Database (NHS EED, via Centre for Reviews and Dissemination (CRD) up to 2015), Health Technology Assessment (HTA) database (via CRD), Research Papers in Economics (RePEc, via EconPapers) and EconLit (Ebsco) (Additional file 1: Appendix 3). We also checked reference lists of other relevant systematic reviews as well as studies included in this review.

Eligibility

Type of study

We included full (cost-effectiveness, cost-utility, or cost-benefit analysis) and partial (cost or cost-consequences analysis) economic evaluations of physical activity mass media campaigns. We used the WHO’s definition of physical activity (“any bodily movement produced by skeletal muscles” [7]). Physical activity mass media campaigns were defined as programs that used persuasive mass media communications to promote physical activity and persuade people to increase or adopt some form of physical activity. We considered both trial-based analysis, where all information used to perform the evaluation is obtained from intervention evidence from single source data, and model-based economic evaluations, where external sources are used to inform inputs for an analysis. We only included peer-reviewed manuscripts and relevant policy reports from trustworthy organisations (e.g. endorsed by governments, conducted independently from the funding body). We excluded systematic reviews and economic evaluations investigating interventions conducted in single settings (e.g., a physical activity campaign in a single school or a workplace). We did not apply any restrictions on publication date, language, or country.

Intervention and population

We included mass media campaigns that used mass media or public communications to persuade, inform, direct or motivate a population to think about, initiate or increase any type of physical activity. Examples of media included TV, radio and newspaper. We excluded narrow reach media, such as brochures and posters. We only included studies reporting media campaigns targeting a whole population or a population subgroup, which could be any age group, the general population, or people with existing conditions. Obesity or non-communicable disease prevention campaigns were included if physical activity was a clearly defined sub-component and physical activity outcomes were reported.

Outcomes

Eligible studies had to report at least one of the following outcomes: mass media campaign awareness, antecedents of physical activity (e.g., attitudes, intentions), and physical activity behaviour change. Incremental cost effectiveness ratio (ICER) was the main outcome of this review. ICERs could be expressed as the incremental cost per change in physical activity, or the incremental cost per QALY gained, or DALY avoided. Secondary outcomes included intervention costs. Additional details on the eligibility criteria are provided in Additional file 1: Appendix 4.

Study selection and data extraction

Two independent reviewers screened all titles and abstracts, followed by full text screening. Any disagreements were discussed and a third reviewer was involved if needed to reach consensus. One reviewer extracted information into a standardised form and a second reviewer checked all data. For costing studies that reported multiple physical activity outcomes, we only extracted data for one selected outcome following this hierarchical order: i) physical activity behaviour; ii) physical activity antecedents, such as knowledge, attitudes, efficacy or intention; iii) mass media campaign awareness, campaign recognition, or campaign message understanding.

Methodological quality assessment

Methodological quality assessment was conducted using the Extended Consensus on Health Economic Criteria list (CHEC-list) (Additional file 1: Appendix 5) [24, 25]. We created a modified version of the CHEC-list to assess the quality of the costing studies (Additional file 1: Appendix 6). The final version was reviewed and approved by three authors. Two independent reviewers rated each study, and a third reviewer was involved in case of disagreements. We considered the information provided in the included study as well as that from any other relevant publication cited in the study, such as an economic evaluation protocol or a second paper where the main trial results were reported.

We also identified additional items relevant to assessing the quality of included studies in the context of the present review questions that were not captured by the CHEC-list (Additional file 1: Appendix 7). All economic evaluations were rated using additional context-specific questions, referred to here as the ‘expanded CHEC-list’.

Assessment of the certainty of model-based economic evaluations for WHO decision-making

We developed a Grading of Recommendations Assessment, Development, and Evaluation (GRADE) style rating to assess the overall quality of the model-based analyses (Additional file 1: Appendix 8). The GRADE style rating was created based on the concepts identified in the GRADE approach [26] as well as previous recommendations for assessing the certainty of evidence from modelling studies [27]. The following domains were considered: A) Quality of model reporting, B) Certainty of model inputs, C) Credibility of model, D) Certainty of model outputs, E) Directness of model. Each domain was rated as “poor”, “fair” or “good” (Additional file 1: Appendix 8, Table 7.A). The overall certainty of each economic model for WHO decision-making was rated as high, moderate, low, or very low by considering the ratings for the individual domains (Additional file 1: Appendix 8, Table 7.B).

Data synthesis

As the included studies were heterogenous in their interventions, methods, data and context, pooling of results was considered inappropriate. Consequently, we present a narrative synthesis of the findings from included studies. Summaries of effect size, cost-effectiveness and costs are reported for each study (where available).

Studies reported costs in different currencies and from different years. Therefore, we expressed monetary values in two ways: i) by year and currency as reported by the authors of the included study, ii) converted to 2020 US dollars to enable comparison of findings. We initially inflated the costs to 2020 using the inflation rate for each country according to inflation rates from the OECD database [28]. Then we transformed the costs in respective currencies into US dollars using purchasing power parity (PPP) conversion factors for 2020 [29].

Results

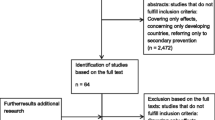

The electronic search yielded 2088 records. An additional 15 studies were identified from hand searching, including screening of other systematic reviews in the field and contact with experts in the field (Fig. 1).

A total of 25 studies, five model-based analyses [30,31,32,33,34] and 20 costing studies [10, 35,36,37,38,39,40,41,42,43,44,45,46,47,48,49,50,51,52,53], were included in this review (Additional file 1: Appendix Table 1). The records excluded at full-text screening and the reasons for exclusion are presented in Additional file 1: Appendix 9.

Question 1: what is the cost-effectiveness and cost-utility of physical activity mass media campaigns?

Study characteristics

We found five model-based analyses investigating the cost-effectiveness of mass media campaigns (Table 1). The types of models used varied across studies and included Markov model [31, 34], OECD SHPeP-NCD (microsimulation 31 years) [32] and Multistate lifestate model [33]. One study did not provide model details [30]. The campaigns varied in terms of type, target population, duration and whether they targeted the regional or national level (Additional file 1: Appendix Table 1). The target populations of the campaigns were adults (n = 3, age range 25-64 years) and both adults and older adults (n = 2, age range 15-79 years) (Additional file 1: Appendix Table 2). These models were all applied to high-income country populations (United States, Australia, New Zealand, Belgium and Italy). The geographical location of the campaigns is presented in Additional file 1: Appendix Table 3. Four studies applied the model to the whole country [30, 32,33,34] whereas one study applied the model to one city in Belgium (Ghent) [31].

The campaigns investigated varied and included: i) one mostly comprised of mass media (“Exercise, you only have to take it regularly not seriously”), ii) two community-wide programs supported by mass media campaigns (“10,000 steps Ghent” and “Wheeling Walks”), iii) a hypothetical mass media campaign following the principles developed in the campaign “Exercise, you only have to take it regularly not seriously”, and iv) a hypothetical mass media campaign promoting the use of physical activity apps. Only three studies reported the baseline physical activity level of the population and only one study reported the impact of the campaign on physical activity in relation to baseline physical activity levels. The impact of physical activity was expressed using different measures, such as Metabolic Equivalent (MET)-min/week (n = 2), moderate-vigorous physical activity (MVPA) MET-min/week (n = 1), walking min/week (n = 1) and percent increase in people considered at least moderately active (n = 1) (Additional file 1: Appendix Table 1).

Additional file 1: Appendix Table 4 presents a description of the approach to model-based analyses used by the five studies. The methods and assumptions used were highly heterogeneous, particularly in terms of selection of physical activity effectiveness measures and assumptions regarding the attenuation of physical activity impact over time. Three studies [30, 31, 34] used the physical activity impact estimates from effectiveness studies, one [32] used the median effectiveness of previous mass media campaigns reported in 12 papers included in a literature review [54], and one [33] used the estimate from a systematic review of interventions that used apps or pedometers to promote physical activity. Overall, the future health benefits of physical activity assumed by the authors were similar, but the reporting of the parameters used (and their sources) was incomplete for most studies. Three studies used parameters that were relevant and appropriate for the population investigated. One study used parameters that were to some extent relevant to the population. One study did not report the parameters and sources, so it is unclear if they were appropriate for the modelled population.

Cost-effectiveness results

The most common perspective adopted was a health system perspective (n = 3) [30, 32, 33], with one [34] study adopting a societal perspective and one [31] a public payer perspective. The time horizon of the models ranged from 20 years to the lifetime of the population investigated. All studies reported the results as additional cost per QALY gained (n = 4) [30, 31, 33, 34] or DALY avoided (n = 1) [32]. Most studies (n = 4) did not report the questionnaires used to generate QALYs and DALYs and one study reported using EQ-5D [31] and used Belgian utility data. The results of the model-based cost-effective analyses studies varied. They ranged from the intervention being more effective and less costly (dominant) in two models [30, 31] to an incremental cost of $130,740 (US 2020) per QALY gained (Table 1) [33]. The results of four models [30,31,32, 34] were considered to show acceptable cost-effectiveness according to implicit thresholds for willingness to pay for each country, as provided by the WHO (Additional file 1: Appendix 10), with Mizdrak (2020) being the only exception (Table 1). Additional file 1: Appendix Table 5 provides additional details on the main economic evaluation findings of the five model-based analyses. Additional file 1: Appendix Table 6 provides a description of cost items and valuation sources used in the model-based analyses.

Methodological quality and certainty of the evidence

Overall, the quality of the model-based analyses, based on the extended CHEC-list, ranged from 11 to 16 out of 20 (Additional file 1: Appendix Table 7). General limitations in the economic evaluations included: limited uncertainty analyses, lack of transparency in the reporting of modelling methods, and lack of systematic methods to identify relevant outcomes and to appraise the quality of the sources of clinical evidence.

Table 2 presents the included studies authors’ conclusions and detailed reviewers’ comments on the approach to the model-based analyses. Overall, studies made overly optimistic assumptions about the sustainability of campaign effects beyond the campaign period, selected inappropriate measures of effectiveness, failed to explore all relevant parameters in sensitivity analyses, did not report all parameters used in the model as well as their sources. In addition, they only reported results for the end of the time horizon investigated instead of presenting intermediate measures which would enhance the interpretability of the findings (Additional file 1: Appendix Table 8).

Our GRADE style rating revealed that the level of certainty of the models ranged from very low (n = 2) to low (n = 3). This indicatesthat we have very little or little confidence that the outputs from the model are reliable for decision making (Additional file 1: Appendix Table 10).

Question 2: what are the costs of physical activity mass media campaigns?

All but one of the model-based analyses (n = 5) [34] reported intervention costs. All of the 20 identified costing studies [10, 35,36,37,38,39,40,41,42,43,44,45,46,47,48,49,50,51,52,53] reported intervention costs only, without performing an economic evaluation (Additional file 1: Appendix Table 1). The campaigns targeted adults (n = 8) [10, 37, 39, 41, 42, 44, 49, 50], both adults and older adults (n = 5) [35, 43, 45, 48, 51], older adults only (n = 1) [36], adolescents (n = 1) [38], children (n = 1) [46], and people across the lifespan (n = 4) [40, 47, 52, 53] (Additional file 1: Appendix Table 2).

All costing studies were conducted in high-income countries except one campaign that was conducted in a middle-income country (Brazil). The geographical location of the campaigns investigated in the costing studies is summarised in Additional file 1: Appendix 4. Amongst the costing studies, the campaign approaches varied and were classified as: mostly mass media (n = 9), community-wide intervention with a mass media campaign (n = 6), mostly community-wide intervention with supportive mass media or media promotions (n = 3), and mass media promotions for single-day events, trails or parks (n = 2) (Table 3). The quality of the costing studies ranged from 3 to 9 out of 15 (median = 6, Additional file 1: Appendix Table 9).

Overall, intervention costs were poorly reported across the 25 included studies, with only Eight (32%) [10, 30, 33, 37,38,39, 43, 45] reporting the total costs as well as the costs of the items contributing to the total costs (Table 4). Eight studies (32%) [32, 36, 41, 44, 46, 47, 49, 53] reported total costs only, without giving details of how the costs were derived. Three studies (12%) [40, 48, 51] reported some costs, but it is unclear if all costs involved in developing and implementing the intervention were considered. Additional file 1: Appendix Table 10 provides a detailed description of total cost, cost per item, cost in the reported currency and year, as well as costs transformed to 2020 US dollars, and cost per week for each of the campaigns.

As limited information on costs was available for the only campaign conducted in a middle-income country (Agita São Paulo), we have reported additional information about this program, from grey literature, in Additional file 1: Appendix 12.

Discussion

There are few economic evaluations of physical activity mass media campaigns available in the literature; all are model-based analyses, and none were conducted in a low, low-middle or middle-income country. The ICER estimates ranged from two interventions being found to be more effective and less costly (dominant) [30, 31], to the highest base case ICER of US$130,740 per QALY gained (US dollars price year 2020) [33]. The level of certainty of the models ranged from very low to low, indicating that we have very little or little confidence that the outputs from the model are reliable for decision making. Therefore, it is unclear to what extent physical activity mass media campaigns offer good value for money.

Overall, it is difficult to estimate the impact of the campaigns on physical activity as studies used different definitions and measures of physical activity, methods of collecting data, and statistical methods. Assessing the effectiveness and long-term benefits of complex population-level public health interventions, such as mass media campaigns, has intrinsic challenges as these interventions cannot be easily evaluated in randomised controlled trials. Additionally, the effectiveness estimates are potentially subject to confounding by other co-occurring community-level interventions. Most of the model-based analyses (n = 4) did not critically appraise the clinical evidence relied on for the modelling. These factors and others that may impact on the effectiveness estimates need to be considered when interpreting the results of the economic evaluations.

The studies included in this review reported on several types of campaigns. No pattern emerged by campaign type, so conclusions cannot be made regarding whether certain types of campaigns are typically more cost-effective than others. The wide range of campaign types, including community-wide interventions and mass media to support the use of a physical activity app, as well as the variety of additional components added to diverse mass media campaigns have made the interpretation of results difficult. It is expected that a mass media campaign conducted within a comprehensive physical activity strategy will be more likely to influence physical activity behaviour in large populations [55]. Unfortunately, it was not possible to explore whether this type of campaign was more cost effective given the small number of economic evaluations included in this review.

All the model-based analyses extrapolated short-term effectiveness results over the long-term to DALYs and QALYS by making assumptions about key parameters, such as attenuation of physical activity impact over time and impact on other health conditions. This introduced further uncertainty into the results reported. Although such assumptions are important for building a model to investigate the long-term impact of interventions, these assumptions were not clearly reported or fully explored in sensitivity analyses. For instance, typically the effectiveness of these campaigns was measured immediately at the end of the campaign, with all the models assuming that the full campaign effect would last for at least 1 year, and any loss in effect was only applied from the second year. It is unclear how sustainable behaviour changes generated by physical activity mass media campaigns are. There is a scarcity of studies reporting physical activity behaviour post-campaign duration, and these studies suggest no change from baseline [10, 56,57,58] or a decline since the post-campaign measure [10, 48, 59]. Therefore the assumption that the effects of the campaign will persist for any period of time beyond the campaign is not supported by the literature.

The results of the current review are aligned with previous reviews of economic evaluations of physical activity interventions, which commonly find scattered evidence [60, 61]. Previous reviews have also highlighted the lack of economic evaluations of physical activity interventions and challenges in interpreting and comparing their results due to the heterogenous methods used, poor reporting and low methodological quality [60, 62, 63]. A previous review conducted by our group investigating the cost-utility of physical activity interventions for older people found that the interventions ranged from cost-saving to $88,000/QALY (US dollar 2018), but all of the interventions investigated structured exercise programs [61], which precludes direct comparison with the results of the current review.

Overall, intervention costs of the mass media campaigns were poorly reported. There is no information on intervention costs for any low and low-middle income countries and only one study reported partial intervention costs for one middle-income country (Agita São Paulo”). We were able to retrieve additional information on the costs of the campaign by contacting the authors and performing a grey literature search. This information should be interpreted with caution as we were unable to find peer-reviewed publications reporting the data and limited information was provided, hindering our appraisal of the quality and usability of the data.

It is unclear whether there is an investment threshold for physical activity mass media campaigns, but it is believed that at least similar levels of investment to those used to fund tobacco control campaigns [64] would be required given the enduring and high prevalence levels of inactivity and the lack of policy levers that are currently available for tobacco. The Centers for Disease Control (CDC) have established investment standards for mass media campaigns for tobacco control [65] and indicated a per capita investment threshold of $1.24 in 2014 US dollar ($1.36 in 2020 US dollar). This threshold is higher than the cost per capita reported in the studies included in this review, which ranged from $0.02 to 0.75 US 2020 dollar. These findings highlight that it is likely that more funding would be needed for physical activity mass media campaigns to generate adequate results.

The overview of the intervention costs presented in this report should be interpreted in the context of the type of campaign, duration and reach. Policymakers and governments who are considering implementation of a physical activity mass media campaign can use this information to inform their budget and campaign planning. The intervention cost information can also be used as an input for future model-based analyses.

Limitations

Although we used a comprehensive search strategy, it is possible that we may have missed economic evaluations of campaigns that were not published in peer-reviewed journals. We did not apply any language restrictions, but we only used keywords in English to search the databases. Therefore, we may have missed studies investigating mass media campaigns in lower- and middle-income countries if they were published in other languages and not indexed in the searched databases. Additionally, the GRADE-style rating was developed and modified for the current review by the authors but its use has yet to be evaluated.

Recommendations for future research

Future modelled economic evaluations should consider selecting appropriate measures of campaign effectiveness, preferably from a systematic review, and making realistic assumptions about attenuation of physical activity effects that are supported by the available evidence. Additionally, future studies should also consider testing all the assumptions in sensitivity analyses, reporting the unit costs and the total cost of the campaigns, clearly reporting the parameters used as well as their sources. In addition to results for the end of the time horizon, authors should also report intermediate results to enhance the interpretability of the models, and these may include: cost-effectiveness considering only trial data, results after utility-weights are applied and results for when time horizon is extended.

Future primary studies investigating physical activity mass media campaigns should consider including a trial-based economic evaluation, particularly those conducted in low-and-middle-income countries. Future costing studies should include and present a detailed breakdown of the elements of an intervention, and these could be grouped into set-up, recurrent, and capital costs. More specifically, authors should report unit costs and all costs involved in the development (set-up) and implementation of physical activity mass media campaigns, such as materials (capital), media (e.g., TV, radio, Billboards), staff (recurrent) and in-kind contributions.

It is strongly recommended that future primary studies and reviews follow standard economic evaluation best-practice recommendations and reporting guidelines, such as the Consolidated Health Economic Evaluation Reporting Standards (CHEERS) statement. Future reviews could focus on social media campaigns as the cost-effectiveness of these may differ to traditional media campaigns.

Conclusion

This review only found five economic evaluations of physical activity mass media campaigns and 20 costing studies reporting the costs of developing and implementing the intervention. All studies were conducted in high-income countries, with exception of one costing study that was conducted in a middle-income country. Overall, it is difficult to interpret the results of the economic evaluations given their high heterogeneity in terms of campaigns characteristics, methods and assumptions, ambiguous reporting and lack of sensitivity analyses exploring uncertainty. The level of certainty of the models were low and therefore it is unclear to what extent physical activity mass media campaign offer good value for money. The information regarding intervention costs should be interpreted considering the type, duration and reach of the campaign. This information can be used for planning future physical activity mass media campaigns or future models investigating the value for money of such campaigns.

Availability of data and materials

All the data generated or analysed during this study are included in this published article and its supplementary information files.

References

Das P, Horton R. Physical activity-time to take it seriously and regularly. Lancet. 2016;388(10051):1254–5.

Powell KE, King AC, Buchner DM, Campbell WW, DiPietro L, Erickson KI, et al. The Scientific Foundation for the physical activity guidelines for Americans, 2nd edition. J Phys Act Health. 2018;16:1–11.

Colorado Division of Workers Compensation USDoH, Human Services PHSAfHR, Quality. Cervical spine injury -- medical treatment guidelines. 2014.

Heath GW, Parra DC, Sarmiento OL, Andersen LB, Owen N, Goenka S, et al. Evidence-based intervention in physical activity: lessons from around the world. Lancet. 2012;380(9838):272–81.

The L. A sporting chance: physical activity as part of everyday life. Lancet. 2021;398(10298):365.

Ding D, Lawson KD, Kolbe-Alexander TL, Finkelstein EA, Katzmarzyk PT, van Mechelen W, et al. The economic burden of physical inactivity: a global analysis of major non-communicable diseases. Lancet. 2016;388(10051):1311–24.

World Health Organization. Global action plan on physical activity 2018–2030: more active people for a healthier world. Geneva: World Health Organization (WHO); 2018.

ISPAH. Eight investments that work for physical activity 2020. https://www.ispah.org/resources/key-resources/8-investments/.

Huhman M, Potter LD, Wong FL, Banspach SW, Duke JC, Heitzler CD. Effects of a mass media campaign to increase physical activity among children: year-1 results of the VERB campaign. Pediatrics. 2005;116(2):e277–84.

Bauman A, McLean G, Hurdle D, Walker S, Boyd J, van Aalst I, et al. Evaluation of the national ‘Push Play’ campaign in New Zealand--creating population awareness of physical activity. N Z Med J. 2003;116(1179):U535.

Craig CL, Bauman A, Gauvin L, Robertson J, Murumets K. ParticipACTION: a mass media campaign targeting parents of inactive children; knowledge, saliency, and trialing behaviours. Int J Behav Nutr Phys Act. 2009;6(1):88.

Yun L, Ori EM, Lee Y, Sivak A, Berry TR. A systematic review of community-wide media physical activity campaigns: an update from 2010. J Phys Act Health. 2017;14(7):552–70.

Leavy JE, Bull FC, Rosenberg M, Bauman A. Physical activity mass media campaigns and their evaluation: a systematic review of the literature 2003-2010. Health Educ Res. 2011;26(6):1060–85.

Bauman A, Chau J. The role of media in promoting physical activity. J Phys Act Health. 2009;6(Suppl 2):S196–210.

Neumann PJ, Sanders GD. Cost-effectiveness analysis 2.0. N Engl J Med. 2017;376(3):203–5.

Shiell A, Donaldson C, Mitton C, Currie G. Health economic evaluation. J Epidemiol Community Health. 2002;56(2):85.

World Health Organization. Active: a technical package for increasing physical activity. Geneva: World Health Organization; 2018. Available from: https://www.who.int/ncds/prevention/physical-activity/active-toolkit/en/.

World Health Organization. ‘Best buys’ and other recommended interventions for the prevention and control of noncommunicable diseases: Updated (2017) appendix 3 of the global action plan for the prevention and control of noncommunicable diseases 2013-2020. Geneva: World Health Organization; 2017. Available from: https://www.who.int/ncds/management/WHO_Appendix_BestBuys.pdf

Moher D, Liberati A, Tetzlaff J, Altman DG, Group P. Preferred reporting items for systematic reviews and meta-analyses: the PRISMA statement. BMJ. 2009;339:b2535.

Thielen FW, Van Mastrigt GAPG, Burgers LT, Bramer WM, Majoie HJM, Evers SMAA, et al. How to prepare a systematic review of economic evaluations for clinical practice guidelines: database selection and search strategy development (part 2/3). Expert Rev Pharmacoecon Outcomes Res. 2016;16(6):705–21.

van Mastrigt GAPG, Hiligsmann M, Arts JJC, Broos PH, Kleijnen J, Evers SMAA, et al. How to prepare a systematic review of economic evaluations for informing evidence-based healthcare decisions: a five-step approach (part 1/3). Expert Rev Pharmacoecon Outcomes Res. 2016;16(6):689–704.

Wijnen BFM, Van Mastrigt GAPG, Redekop WK, Majoie HJM, De Kinderen RJA, Evers SMAA. How to prepare a systematic review of economic evaluations for informing evidence-based healthcare decisions: data extraction, risk of bias, and transferability (part 3/3). Expert Rev Pharmacoecon Outcomes Res. 2016;16(6):723–32.

Pinheiro M. Systematic review of economic evaluations of physical activity public education communication campaigns 2021 Available from: https://bit.ly/3tKSBZ3.

Evers S, Goossens M, de Vet H, van Tulder M, Ament A. Criteria list for assessment of methodological quality of economic evaluations: consensus on health economic criteria. Int J Technol Assess Health Care. 2005;21(2):240–5.

Odnoletkova I, Goderis G, Pil L, Nobels F, Aertgeerts B, Annemans L, et al. Cost-effectiveness of therapeutic education to prevent the development and progression of type 2 diabetes: systematic review. J Diabetes Metab. 2014;5(9):1000438.

Guyatt GH, Oxman AD, Vist GE, Kunz R, Falck-Ytter Y, Alonso-Coello P, et al. GRADE: an emerging consensus on rating quality of evidence and strength of recommendations. BMJ. 2008;336(7650):924–6.

Brozek JL, Canelo-Aybar C, Akl EA, Bowen JM, Bucher J, Chiu WA, et al. GRADE guidelines 30: the GRADE approach to assessing the certainty of modelled evidence: an overview in the context of health decision-making. J Clin Epidemiol. 2021;129:138–50.

OECD. Inflation (CPI) (indicator). 2022.

OECD. Purchasing power parities (PPP) (indicator). 2022.

Cobiac LJ, Vos T, Barendregt JJ. Cost-effectiveness of interventions to promote physical activity: a modelling study. PLoS Med. 2009;6(7):e1000110.

De Smedt D, De Cocker K, Annemans L, De Bourdeaudhuij I, Cardon G. A cost-effectiveness study of the community-based intervention '10 000 steps Ghent'. Public Health Nutr. 2012;15(3):442–51.

Goryakin Y, Aldea A, Lerouge A, Romano Spica V, Nante N, Vuik S, et al. Promoting sport and physical activity in Italy: a cost-effectiveness analysis of seven innovative public health policies. Ann Ig. 2019;31(6):614–25.

Mizdrak A, Telfer K, Direito A, Cobiac LJ, Blakely T, Cleghorn CL, et al. Health gain, cost impacts, and cost-effectiveness of a mass media campaign to promote smartphone apps for physical activity: modeling study. JMIR mHealth uHealth. 2020;8(6):e18014.

Roux L, Pratt M, Tengs TO, Yore MM, Yanagawa TL, Van Den Bos J, et al. Cost effectiveness of community-based physical activity interventions. Am J Prev Med. 2008;35(6):578–88.

Wray RJ, Jupka K, Ludwig-Bell C. A community-wide media campaign to promote walking in a Missouri town. Prev Chronic Dis. 2005;2(4):A04.

Stackpool G. 'Make a move' falls prevention project: an area health service collaboration. Health Promot J Austr. 2006;17(1):12–20.

Reger-Nash B, Fell P, Spicer D, Fisher BD, Cooper L, Chey T, et al. BC walks: replication of a communitywide physical activity campaign. Prev Chronic Dis. 2006;3(3):A90.

Peterson M, Chandlee M, Abraham A. Cost-effectiveness analysis of a statewide media campaign to promote adolescent physical activity. Health Promot Pract. 2008;9(4):426–33.

Merom D, Miller Y, Lymer S, Bauman A. Effect of Australia's walk to work day campaign on adults' active commuting and physical activity behavior. Am J Health Promot. 2005;19(3):159–62.

Mahecha Matsudo S, Rodrigues Matsudo V, Leandro Araujo TL, Roque Andrade D, Luiz Andrade E, De Oliveira LC, et al. The Agita Sao Paulo Program as a model for using physical activity to promote health. Rev Panam Salud Publica. 2003;14:265–72.

Leavy JE, Rosenberg M, Bauman AE, Bull FC, Giles-Corti B, Shilton T, et al. Effects of find thirty every day: cross-sectional findings from a Western Australian population-wide mass media campaign, 2008-2010. Health Educ Behav. 2013;40(4):480–92.

Kite J, Thomas M, Grunseit A, Li V, Bellew W, Bauman A. Results of a mixed methods evaluation of the make healthy Normal campaign. Health Educ Res. 2020;35(5):418–36.

Kite J, Gale J, Grunseit A, Bellew W, Li V, Lloyd B, et al. Impact of the make healthy Normal mass media campaign (phase 1) on knowledge, attitudes and behaviours: a cohort study. Aust N Z J Public Health. 2018;42(3):269–76.

King EL, Grunseit AC, O'Hara BJ, Bauman AE. Evaluating the effectiveness of an Australian obesity mass-media campaign: how did the ‘Measure-Up’ campaign measure up in New South Wales? Health Educ Res. 2013;28(6):1029–39.

John-Leader F, Van Beurden E, Barnett L, Hughes K, Newman B, Sternberg J, et al. Multimedia campaign on a shoestring: promoting ‘Stay active - stay Independent’ among seniors. Health Promot J Austr. 2008;19(1):22–8.

Huhman ME, Potter LD, Nolin MJ, Piesse A, Judkins DR, Banspach SW, et al. The influence of the VERB campaign on children's physical activity in 2002 to 2006. Am J Public Health. 2010;100(4):638–45.

Huberty J, Dodge T, Peterson KR, Balluff M. Creating a movement for active living via a media campaign. Am J Prev Med. 2012;43(5 Suppl 4):S390–1.

Hillsdon M, Cavill N, Nanchahal K, Diamond A, White IR. National level promotion of physical activity: results from England's ACTIVE for LIFE campaign. J Epidemiol Community Health. 2001;55(10):755–61.

Clark S, Bungum TJ, Meacham M, Coker L. Happy trails: the effect of a media campaign on urban trail use in Southern Nevada. J Phys Act Health. 2015;12(1):48–51.

Buchthal OV, Doff AL, Hsu LA, Silbanuz A, Heinrich KM, Maddock JE. Avoiding a knowledge gap in a multiethnic statewide social marketing campaign: is cultural tailoring sufficient? J Health Commun. 2011;16(3):314–27.

Brown WJ, Mummery K, Eakin E, Schofield G. 10,000 steps Rockhampton: evaluation of a whole community approach to improving population levels of physical activity. J Phys Act Health. 2006;3(1):1–14.

Berry TR, Yun L, Faulkner G, Latimer-Cheung AE, O'Reilly N, Rhodes RE, et al. Population-level evaluation of ParticipACTION's 150 play list: a mass-reach campaign with mass participatory events. J Health Promot Educ. 2020;58(6):297–310.

Bell AC, Wolfenden L, Sutherland R, Coggan L, Young K, Fitzgerald M, et al. Harnessing the power of advertising to prevent childhood obesity. Int J Behav Nutr Phys Act. 2013;10(1):1–0.

Goryakin YGM, Lerouge A, Pellegrini T, Cecchini M. The case of obesity prevention in Italy. Italy: Ministry of Health; 2017.

Cavill N, Bauman A. Changing the way people think about health-enhancing physical activity: do mass media campaigns have a role? J Sports Sci. 2004;22(8):771–90.

Verheijden MW, van Dommelen P, van Empelen P, Crone MR, Werkman AM, van Kesteren NM. Changes in self-reported energy balance behaviours and body mass index during a mass media campaign. Fam Pract. 2012;29(Suppl 1):i75–81.

Wimbush E, MacGregor A, Fraser E. Impacts of a national mass media campaign on walking in Scotland. United Kingdom: Oxford University Press; 1998. p. 45–53.

Bélanger-Gravel A, Laferté M, Therrien F, Lagarde F, Gauvin L. The overall awareness and impact of the WIXX multimedia communication campaign, 2012-2016. J Phys Act Health. 2019;16(5):318–24.

Meyer AJ. Skills training in a cardiovascular health education campaign. J Consult Clin Psychol. 1980;48(2):129–42.

Abu-Omar K, Rütten A, Burlacu I, Schätzlein V, Messing S, Suhrcke M. The cost-effectiveness of physical activity interventions: a systematic review of reviews. Prev Med Rep. 2017;8:72–8.

Taylor J, Walsh S, Kwok W, Pinheiro M, Oliveira J, Bauman A, et al. Physical activity interventions for older adults - scoping report for the World Health Organization. Geneva: World Health Organization: WHO; 2020.

Cochrane M, Watson PM, Timpson H, Haycox A, Collins B, Jones L, et al. Systematic review of the methods used in economic evaluations of targeted physical activity and sedentary behaviour interventions. Soc Sci Med. 2019;232:156–67.

Gebreslassie M, Sampaio F, Nystrand C, Ssegonja R, Feldman I. Economic evaluations of public health interventions for physical activity and healthy diet: a systematic review. Prev Med. 2020;136:106100.

Grunseit A, Bellew B, Goldbaum E, Gale J, Bauman A. In: Centre TAPP, editor. Mass media campaigns addressing physical activity, nutrition and obesity in Australia: an updated narrative review. Sydney. 2016.

Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Best Practices for Comprehensive Tobacco Control Programs. In: Department of Health and Human Services CfDCaP, National Center for Chronic Disease Prevention and Health Promotion, Office on Smoking and Health, editor. Atlanta. 2014.

Acknowledgements

Not applicable.

Funding

The report on which this work is based was prepared for and funded by the Physical Activity Unit, Department of Health Promotion, Division of Universal Health Coverage and Healthier Populations, World Health Organization (WHO), Geneva. The funding body (WHO) was involved in the design of the study, analysis, interpretation of data and manuscript writing. MBP and DD are supported by fellowships from the National Health and Medical Research Council (NHMRC), Australia. BS is supported by the Western Sydney Local Health District (WSLHD). AT is supported by a University of Sydney Robinson Fellowship. NHMRC and the WSLHD did not have any role in the study. No financial disclosures were reported by the other authors of this paper.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

MBP, KH, CS, AB, AT and SN acquired the funding for this project. MBP led the project, with supervision of KH, CS, AB and SN. MBP, KH, CS, AB, AT, AS, FB, JW and SN conceptualised the study. MBP, KH, CS, AB, BS, DD, AT, AS, FB, JW and SN were developed the methodology. MBP, NC, BW, BSA, FRL and VB were responsible for data curation. MBP, KH, CS, NC, AS, FB, JW, BW and SN conducted formal analysis. MBP, KH, AB, NC, BS, WB, BW, BSA, FRL, VB and SN were responsible for data validation. MBP, AS, FB, JW and SN were responsible for data visualisation. MBP wrote the original draft, which was reviewed by all authors. The author(s) read and approved the final manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate

Not applicable.

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Competing interests

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

Additional information

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary Information

Additional file 1: Appendix 1.

PRISMA checklists. Appendix 2. Glossary. Appendix 3. Search strategy. Appendix 4. Inclusion and exclusion criteria. Appendix 5. Quality assessment of economic evaluations included in the review using the Extended Consensus on Health Economic Criteria list (CHEC-list). Appendix 6. Quality assessment of costing studies using a modified version of the Consensus Health Economic Criteria List (CHEC-list). Appendix 7. Expanded CHEC-list: Additional questions on the quality of economic evaluations of physical activity mass media campaigns. Appendix 8. GRADE style rating for model-based economic evaluation of physical activity mass media campaigns. Appendix 9. Records excluded at full-text screening and reasons for exclusion. Appendix 10. Implicit thresholds for willingness to pay for each country provided by WHO team. Appendix 11. Application of the GRADE style rating to assess the certainty of each economic model for WHO decision-making. Appendix 12. Additional resources on Agita São Paulo campaign. Appendix table 1. Characteristics of studies included in this review according to study type: model-based analyses and costing studies. Appendix table 2. Mass media campaigns by target population. Appendix table 3. Mass media campaigns by geographical location. Appendix table 4. Description of the approach to the model-based analyses of economic evaluations of physical activity mass media campaigns. Appendix table 5. Main economic evaluation findings of model-based analyses of physical activity mass media campaigns. Appendix table 6. Description of cost items and valuation sources used in the economic evaluations of physical activity mass media campaign. Appendix table 7. Quality of economic evaluation of physical activity mass media campaigns according to CHEC-List. Appendix table 8. Expanded CHEC-list: Additional questions on the quality of economic evaluations of physical activity mass media campaigns. Appendix table 9. Quality of costing studies according to a modified version of CHEC-list. Appendix table 10. Intervention costs description

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/. The Creative Commons Public Domain Dedication waiver (http://creativecommons.org/publicdomain/zero/1.0/) applies to the data made available in this article, unless otherwise stated in a credit line to the data.

About this article

Cite this article

Pinheiro, M.B., Howard, K., Sherrington, C. et al. Economic evaluation of physical activity mass media campaigns across the globe: a systematic review. Int J Behav Nutr Phys Act 19, 107 (2022). https://doi.org/10.1186/s12966-022-01340-x

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/s12966-022-01340-x